Introduction

Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a rare, acute, severe renal infection characterized by necrosis, abscesses and gas, which may involve both the renal parenchyma and perirenal tissues.1,2This condition is more frequent in women (female-to-male ratio of 4:1)2 and may be the result of bacterial activity generated by diabetes mellitus (DM)2-4 and urinary obstruction caused by renal lithiasis.4 Emphysematous pyelonephritis leads to production of gas via the fermentation of glucose.5

The clinical course of patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis is variable and depends on early diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment. In the 1970s and 1980s, the overall mortality rate for this condition was up to 78% in cases that did not receive timely care, with emergency nephrectomy being the only suitable treatment.6 However, this rate has substantially decreased in recent decades with the early introduction of appropriate antibiotic therapy and multidisciplinary management.7

The following is the case of a patient with DM, high blood pressure, chronic kidney disease (CKD) on hemodialysis, bilateral staghorn calculi and recurrent urinary tract infections, who was diagnosed with emphysematous pyelonephritis.

Case presentation

47-year-old woman with a history of high blood pressure (under treatment with losartan 100mg every 24 hours), DM (with poor adherence to therapy), CKD (being treated with hemodialysis 3 times a week in the last 2 years and with an approximate diuresis of 1 500 mL/24 hours) and hypothyroidism (under treatment with levothyroxine 50pg every 24 hours). In the last year, the patient had had two episodes of acute pyelonephritis that required hospitalization, and since she was diagnosed with stage 3 and 4 CKD (3 years earlier) she discontinued the use of hypoglycemic drugs. Due to CKD, the patient had moderate anemia and was being treated with parenteral iron and erythropoietin at each hemodialysis session because she presented a dramatic drop in hemoglobin levels after these interventions.

During a regular hemodialysis session, the patient developed tachycardia, fever and chills, so she was referred to the emergency department of a tertiary care center in Lima, Peru. It should be noted that two days before admission she presented with colicky abdominal pain in the left flank that subsided with analgesics. On admission to the emergency department, the patient was conscious, hemodynamically stable and with the following vital signs: blood pressure: 120/78 mmHg, heart rate: 118 bpm, respiratory rate: 20 rpm, and temperature: 37.0°C. The physical examination also revealed pain on palpation in the left flank and positive bilateral kidney percussion.

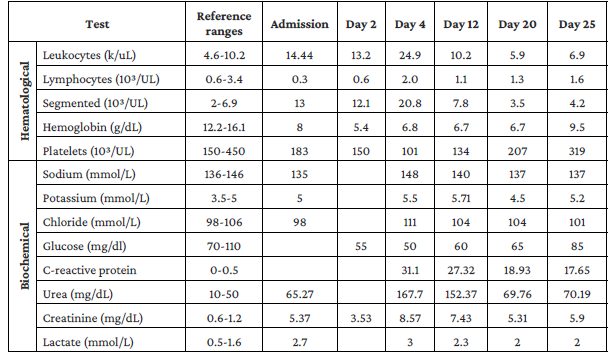

Laboratory tests on admission showed leukocytosis, moderate anemia, leukocyturia and high lactic acidosis (Table 1), so empirical antibiotic therapy was started with ceftriaxone 2g intravenous every 24 hours for 4 days. Given the unavailability of beds, the patient remained in the emergency room for 4 days before being admitted to the general inpatient ward.

Renal ultrasound, performed 48 hours after admission, showed a 104x53mm right kidney with irregular borders, heterogeneous echotexture, poor corticomedullary differentiation, 4mm parenchyma, and lithiasis inside, but without signs of hydronephrosis. It was not possible to see the left kidney during this procedure, so a contrasted CT scan was requested, which, due to hospital availability limitations, could not be performed until the fifth day of hospitalization.

After 96 hours of admission, the patient presented hypoactivity and high blood pressure with no response to hydration. Considering the suspicion of infection by resistant bacteria, it was decided to suspend ceftriaxone and initiate meropenem 500mg every 24 hours and vancomycin 500mg every 48 hours (dose adjusted according to the patient's renal function). Also, due to septic shock, norepinephrine was started at 1 pg/hour/min and transfer to the critical care unit was indicated.

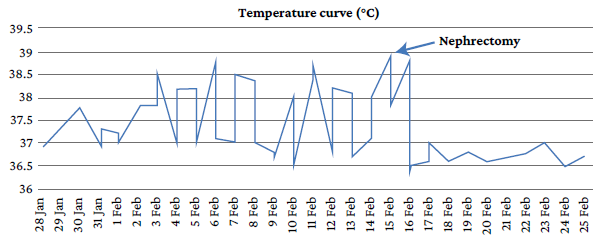

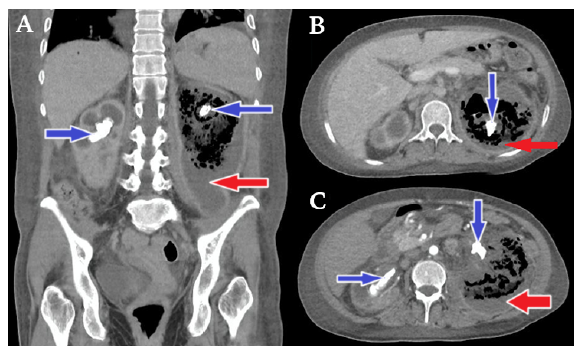

On the fifth day of admission, due to the persistence of intermittent fever (Figure 1), hypoactive delirium and hypoglycemia, as well as the presence of oliguria with purulent urine and the need for vasopressors, a contrast computed tomography urogram was performed (Figure 2), which showed the following: 1) right kidney of 108x54x43mm with staghorn calculi of 46x41x16mm inside and dilatation of the pyelocaliceal system of up to 23mm.; 2) left renal fossa of 236x87x88mm with loss of renal morphology due to the presence of gas and air-fluid levels (destruction of the renal parenchyma); 3) scarce contrast-enhancing parenchymal areas in the collecting and intraparenchymal system, and 4) presence of staghorn calculi in the upper pole (29x14mm), interpolar region (23x17mm) and proximal ureteropelvic junction (24x15mm). Based on these findings compatible with emphysematous pyelonephritis and coraliform lithiasis, it was decided to continue with the antibiotic therapy already established.

→ Perirenal collection mixed with liquefied necrotic purulent fluid settled in the fundus with air in the upper part giving rise to renal air-fluid levels, a finding suggestive of class 3B emphysematous pyelonephritis in the left kidney according to Huang's classification.

→ Bilateral staghorn calculi with characteristics of coralliform lithiasis.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 2 Contrast computed tomography urogram.

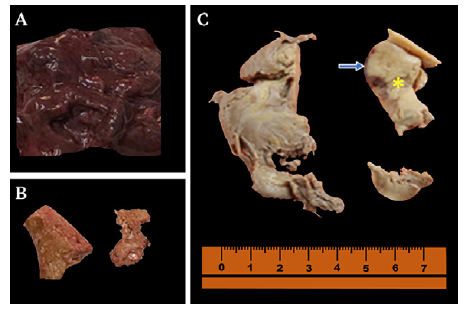

On the 18th day of hospitalization and due to the persistence of intermittent fever and septic shock, it was decided to perform a left nephrectomy, procedure that had no complications (surgical and pathological anatomy findings are shown in Figures 3 and 4). After surgery, an improvement (albeit slow) in the patient's clinical condition was observed, which allowed discontinuing antibiotic therapy 5 days after nephrectomy (i.e., 23 days of antibiotic therapy in total) and the patient was able to continue receiving her hemodialysis sessions without fever and without the need for vasopressor therapy. Finally, 25 days after her hospital admission, the patient was discharged with indication for outpatient follow-up, after which she was counter-referred to her primary care center.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 3 Pathological anatomy: macroscopy of removed kidney. A) Necrotic and hemorrhagic kidney, friable consistency (unfixed kidney); B) Yellowish staghorn calculi; C) Kidney (fixed in 10% formalin) opaque brown with light yellowish (yellow asterisk) and dark brownish (blue arrow) areas in the cortico-medullary zone and pyelocaliceal system.

Source: Own elaboration.

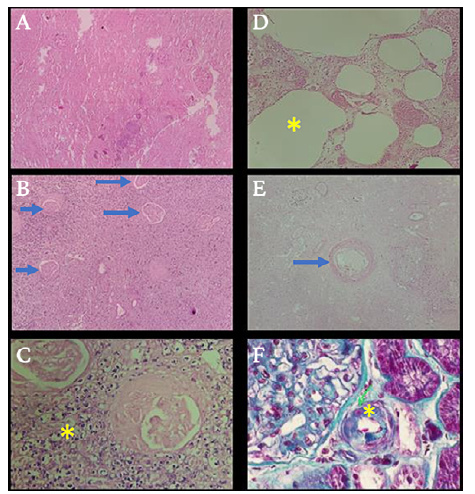

Figure 4 Pathological anatomy: microscopy (histopathological study) of the removed kidney. A) No viable renal tissue is identified, ischemic necrosis of glomeruli, tubules and blood vessels [hematoxylin and eosin, 80x]; B) Necrotic and sclerosed glomeruli (blue arrows), and interstitium with mixed inflammatory infiltrate [hematoxylin and eosin, 80x]; C) Neutrophils and lymphocytes (yellow asterisk) [hematoxylin and eosin, 800x]; D) Empty ovoid spaces (yellow asterisk) probably filled with gas prior to tissue processing [hematoxylin and eosin, 400x]; E) Arteriola (green arrow) with slight hyaline sclerosis [hematoxylin and eosin, 200x]; F) Enhancement of collagen fibers, blue color (yellow asterisk) [Masson's trichrome, 400x].

Discussion

Emphysematous pyelonephritis is an acute and severe necrotizing renal infection8 that poses a urological emergency,6 so both diagnosis and treatment should be initiated early.7 In order to diagnose this condition, a high index of clinical suspicion is required, particularly in women2 and in patients with DM,2,3immunocompromised,2 and urinary tract obstructions.4,9Although the outcome in the present case was satisfactory, it should be noted that the diagnosis was late due to initial limitations regarding access to contrast tomography and nephrectomy at the institution, as well as the hemodynamic instability of the patient. Therefore, in centers where CT or MRI scans are available, these tests should be performed in the first hours of care of patients with pyelonephritis and renal dysfunctions in order to define the treatment to be followed.

Coraliform lithiasis is one of the most severe forms of renal lithiasis. It is usually associated with urinary tract infections by ureolytic bacteria,10 some of which behave as facultative anaerobic bacteria that may lead to the destruction of the renal parenchyma in situations of low oxygen concentration through the development of gas, abscesses and renal necrosis.5,6

Escherichia coli is the most frequently detected pathogen in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis,2,6,9followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae,2 , 6 , 9Proteus mirabilis,6 other enterobacteria (Enterobacter aerogenes and Citrobacter freundií),9Pseudomonas,2 group D Streptococcus, and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus.6 In some cases, polymicrobial infection has also been reported.11 In the present case, Streptococcus sp and Escherichia coli, both carbapenemase-producing strains, were isolated in urine cultures, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was isolated in blood cultures and, after nephrectomy, Proteus mirabilis, an extended-spectrum ß-lactamase-producing strain, was found in the culture of the resected kidney.

Although sometimes the symptomatology of pyelonephritis is not very specific, the symptoms and signs it causes include fever, vomiting, lumbar pain, dysuria, dyspnea, crepitus and pneumaturia, the latter 3 being less frequent.6 In the case reported here, during hospitalization the patient presented abdominal pain and persistent fever, despite receiving broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotic therapy with third-generation cephalosporins, as well as septic shock and impaired consciousness, conditions strongly associated with mortality in cases of emphysematous pyelonephritis.7

Patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis usually exhibit leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia and impaired renal function, all of which are poor prognostic factors.12 In this case, the patient not only had leukocytosis and thrombocytopenia, but also persistent symptomatic hypoglycemia; in addition, her impaired renal function was related to the presence of CKD as a complication resulting from poor adherence to treatment for DM.

Since the diagnosis of emphysematous pyelonephritis is radiological, the development of new diagnostic imaging techniques has made it easier to make a more accurate diagnosis.13 Computed axial tomography (CAT) is the test of choice as it allows the identification of intraparenchymal or perinephric air, necrosis and heterogeneous multilocular fluid collections.6,14Moreover, it not only allows the diagnosis of this condition, but also its classification depending on its extension.13

Emphysematous pyelonephritis, according to the proposal of Wan et al.15 made in 1996, is classified in two groups: type I, which refers to renal necrosis with total absence of fluid content on CT or the presence of a streaky/mottled gas pattern demonstrated on radiograph or CT with lung window display, and type II, which is characterized by the presence of adrenal fluid associated with a bubbling gas pattern or by the presence of gas in the collecting system. However, this classification is no longer in use, and the one currently used is the classification suggested in 2000 by Huang & Tseng,9,16who, based on tomographic findings and looking for a quick decision making process for the management of patients with this condition, proposed 4 groups: class 1: presence of gas only in the collecting system; class 2: presence of gas in the renal parenchyma without extension to the extrarenal area; class 3, divided into 3A: extension of gas or abscess in the perirenal space and 3B: extension of gas or abscess in the pararenal space; and class 4: bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis.

Mortality in emphysematous pyelonephritis increases progressively depending on the class, with class 4 having the worst prognosis. In the present case, the tomographic findings of the patient were compatible with class 3B emphysematous pyelonephritis.

There is currently no consensus on the best treatment for emphysematous pyelonephritis2 and, in general, regardless of its class, it is recommended that not only supportive medical treatment and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy be implemented, but also percutaneous drainage and, in the most severe cases, nephrectomy.3 Thus, percutaneous drainage combined with broad-spectrum antibiotics has been described as the indicated treatment for patients with class 3A and 3B emphysematous pyelonephritis who have less than 2 risk factors (thrombocytopenia, acute deterioration of renal function, altered state of consciousness, and septic shock),4,11,16whereas nephrectomy is indicated for patients with class 4 or class 3A and 3B emphysematous pyelonephritis with more than 2 risk factors4,17In the present case, since the patient presented class 3B emphysematous pyelonephritis and had more than 2 risk factors, CKD with the need for hemodialysis and chorionic lithiasis, a nephrectomy was performed.

Antibiotic therapy should be started early and be directed mainly against gram-negative bacteria, as these are the most frequently isolated etiologic agents.11,17The duration of treatment varies depending on the surgical management and the clinical status, comorbidities, and clinical progress of the patient. In the present case, the extent of the lesion, the presence of drug-resistant bacteria and the multiple comorbidities would explain her initially unfavorable progress, so it is important to emphasize that the patient's condition improved after nephrectomy despite the presence of carbapenemase-producing bacteria.

According to the literature, there are some factors that are associated with increased mortality in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis, namely: having bilateral emphysematous pyelonephritis, having class 1 emphysematous pyelonephritis, having thrombocytopenia, receiving only conservative treatment (fluid resuscitation, administration of antimicrobials, and control of DM without percutaneous drainage),18 having elevated creatinine levels, and presenting septic shock and altered consciousness.19 In the present case, despite the patient's multiple comorbidities and the presence of poor prognostic factors (emphysematous pyelonephritis, thrombocytopenia, septic shock, and altered consciousness), a slow but satisfactory clinical progress was achieved by initiating antibiotic therapy and performing a nephrectomy.

Conclusion

Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a rare and severe infection that should always be suspected in women with DM with poor adherence to therapy, poor response to antibiotic therapy, and chorionic lithiasis. Since it is a urological emergency, its early diagnosis and timely treatment are essential, being CT the diagnostic test of choice because it not only allows to make the diagnosis, but also to establish the prognosis and the most appropriate treatment.