Introduction

Intestinal nonrotation (INR) constitutes a part of the spectrum of intestinal malrotation abnormalities that occur in embryonic development1,2. The true incidence of the pathology is difficult to determine due to the asymptomatic or non-specific course in a significant group of patients1.

INR occurs due to intestinal rotation failure and retroperitoneal fixation2,3. Although patients may remain asymptomatic throughout their lives, complications include intestinal obstruction, volvulus, venous congestion, and diagnostic errors in patients with appendicitis due to unconventional location2.

Case presentation

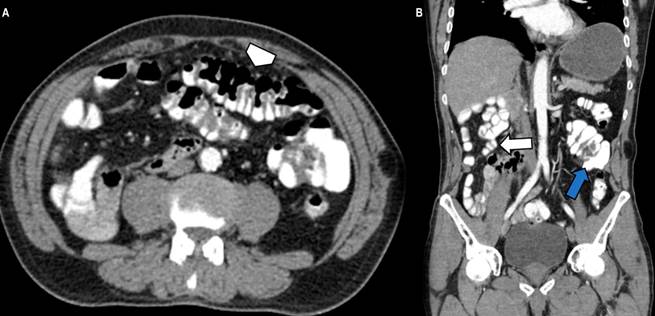

We present the case of a 73-year-old male patient who attended surgery due to pain in the right inguinal region associated with a sensation of an ipsilateral mass. He has no significant personal or family history. No positive findings were reported during the physical examination. A contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen was indicated as a study method, identifying the transverse and ascending colon in the mesogastrium without crossing the midline and loss of the “C” shape of the duodenum located in the right hemiabdomen of the small intestine (Figures 1A and B).

Source: Authors’ archive.

Figure 1 Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen in the axial section and coronal reconstruction. A. The transverse colon is located in the left hemiabdomen (arrowhead). B. Cecum and ileocecal valve on the left flank (blue arrow), thin intestinal loops in the right hemiabdomen (white arrow).

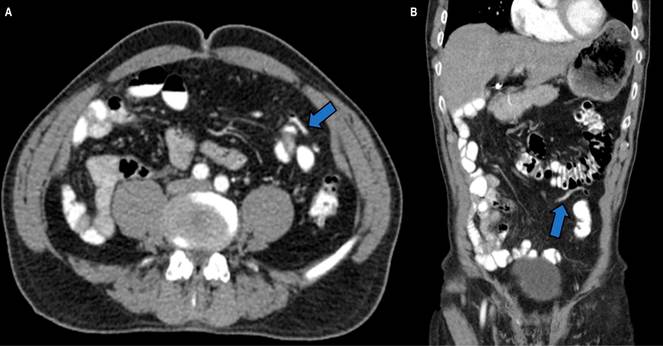

The abnormal location of the cecum, ileocecal valve, and cecal appendix in the left flank and mesogastrium was observed (Figures 1A and B, 2A and B).

Source: Authors’ archive.

Figure 2 Abdominal CT scan in the axial plane (A) and coronal reconstruction (B). The cecal appendix with contrast medium and air inside on the left flank (blue arrow).

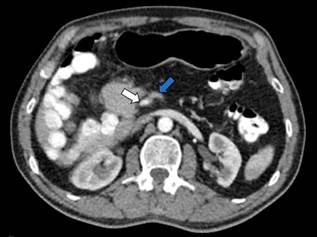

There is an inversion of the relationship of the superior mesenteric vessels, where the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) was located to the left of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), confirming the diagnosis (Figure 3).

Source: Authors’ archive.

Figure 3 Abdominal CT scan in the axial plane. Inversion of the artery-vein relationship with the location of the SMV (blue arrow) to the left of the SMA (white arrow).

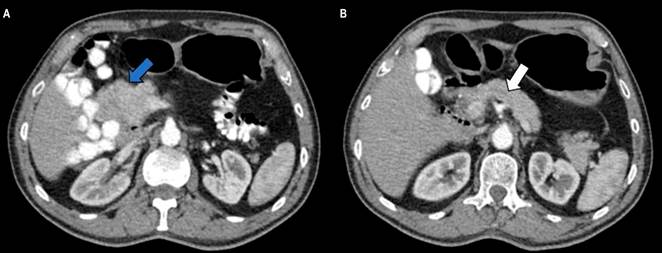

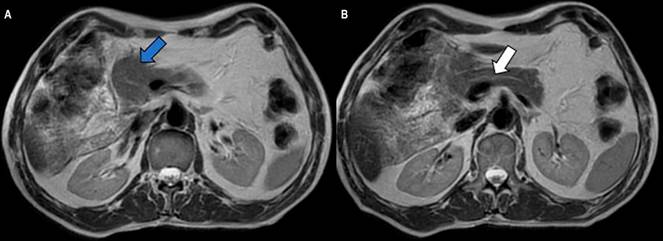

Additionally, a globular deformity of the head of the pancreas was identified in the CT study (Figures 4A and B), later corroborated by additional MRI studies of the abdomen, with no evidence of dilation of the pancreatic duct (Figures 5A and B).

Source: Authors’ archive.

Figure 4A and B. Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen in axial sections. Globular deformity of the head of the pancreas (blue arrow) and absence of dilation of the pancreatic duct (white arrow).

Source: Authors’ archive.

Figure 5A and B. MRI of the abdomen in axial sections. Globular deformity of the head of the pancreas (blue arrow) and absence of dilation of the pancreatic duct (white arrow).

INR findings were considered in the context of an asymptomatic patient. Without symptoms or surgery criteria, expectant management of his condition and follow-up by the gastroenterology service were proposed. As a limitation, this study lacks additional endoscopic studies due to the absence of symptoms, the incidental nature of the finding, and the diagnosis confirmed by CT and MRI.

Discussion

Intestinal rotation occurs during the fourth and twelfth weeks of gestation2. Intestinal embryonic development has been divided into three stages. In stages 1 and 2, the extrusion of the midgut towards the extraembryonic cavity occurs with a rotation of 90º and 270º counterclockwise3; this rotation brings the duodenal loop behind the SMA with the ascending colon on the right, the transverse colon on the upper side, and the descending colon on the left4. Stage 3 involves fusion and anchoring of the mesentery3,4.

Intestinal malrotation mainly affects the midgut in stage 2, generating the spectrum of manifestation of INR, malrotation, and reverse rotation3. INR refers to a failure in the counterclockwise rotation of the midgut, resulting in the mispositioning of the duodenojejunal junction to the right of the midline5. Finally, the ligament of Treitz will be located on the right side of the abdomen, and the terminal ileum will cross the midline to meet the cecum in the left hemiabdomen instead of the right6.

INR occurs in approximately 1 in every 500 live births and has been described in 0.5% of autopsies(4). A slight predominance has been reported in male patients with a wide age range at manifestation, from 18 to 97 years, according to the literature(7,8). Intestinal rotation abnormalities are usually asymptomatic; however, they can be combined with symptoms of intermittent or chronic abdominal pain(7,8). A study by Nehra and Goldstein reported nausea and diarrhea as the most common symptoms in patients with intestinal malrotation; other less frequent symptoms were emesis, abdominal pain and distension, dyspepsia, diarrhea, and constipation(6,7). Even if symptoms are present, it is difficult to attribute them to INR definitively; an abdominal CT study reported that up to 94% of patients with INR were asymptomatic(8,9). Other forms of manifestation include intestinal intussusception, although it is uncommon and often has a pathological starting point, such as a gastrointestinal malignancy or polyp(9,10).

Although INR in adult patients has a lower risk of volvulus since the base of the mesentery is wider than in malrotation, it may manifest as acute intestinal obstruction and intestinal ischemia10-12 (Table 1).

Table 1 Symptoms reported in intestinal malrotation

| Chronic (80% of patients) | Complications |

|---|---|

| Nausea and emesis | Intestinal obstruction |

| Intermittent abdominal pain | Intussusception |

| Early satiety | Volvulus |

| Dyspepsia, abdominal distension | Internal hernia |

| Diarrhea, constipation | Intestinal ischemia |

Prepared by the authors.

Early diagnosis can prevent the complications of midgut volvulus and small bowel necrosis; however, it can be difficult radiologically; symptomatic patients may warrant laparoscopic or open exploration to confirm the diagnosis9.

Among the diagnostic imaging available are simple X-rays, the use of which is limited, although they may show some evidence of an abnormally located intestine9. For fluoroscopy studies, sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 77%, respectively, are reported for the diagnosis, showing the duodenojejunal junction that does not cross the midline and the mispositioning of the ascending colon and the cecum6,9. Ultrasound findings include inversion of the SMV and SMA13.

CT reveals an inverse relationship between SMA and SMV, as observed in this clinical case14. Other findings include the location of the small intestine on the right side with the absence of a retroperitoneal segment of the duodenum and a cecum on the left side14. The “swirl” sign may be present, indicating twisting of the blood vessels around the mesenteric pedicle7,14.

In the context of volvulus or obstruction, an abrupt transition in intestinal diameter may be visible15. Signs suggesting ischemia can be seen as increased attenuation or absence of enhancement of the intestinal wall, pneumatosis intestinalis, or thickening of the large intestine wall15. The pneumoperitoneum may be visible as a sign of perforation15 (Table 2). Research by Xiong at Tongji Hospital concludes that using abdominal CT can improve reader confidence in identifying asymptomatic cases of malrotation, reducing the proportion found in the configuration of volvulus and allowing classification into multiple potentially relevant subtypes8.

Table 2 CT findings in intestinal nonrotation

| Tomographic findings | Complications |

|---|---|

| Inversion of the SMA and SMV relationship | Pneumoperitoneum |

| Small intestine in the right hemiabdomen | Intestinal pneumatosis |

| Large intestine in the left hemiabdomen | Absence of enhancement of the intestinal wall |

| Absence of the retroperitoneal segment of the duodenum | Thickening of the intestinal wall |

| “Swirl” sign of mesenteric vessels | Findings of intestinal obstruction |

| Engorgement of mesenteric blood vessels | |

| Malformations of the head and uncinate process of the pancreas |

Prepared by the authors.

MRI is not commonly used in this context; however, if there is suspicion of inversion of the SMA and SMV relationship, it is usually helpful16. MRI and magnetic resonance cholangiography are better tools than CT to define the anatomy of the biliary tree and pancreatic duct. They are more capable of evaluating pancreatic and intrahepatic masses, making them diagnostic support for incidental findings, as in this clinical case14,17.

A study by Chandra et al. described the frequency of normal variations in the contour of the head and the uncinate process of the pancreas in patients with intestinal malrotation, some of which can mimic a neoplasia18. The authors described the globular form as the most common variant, as in this clinical case, followed by the elongated form and a third mixed form (globular and elongated)18. Ninety percent of the patients in the study exhibited an inversion of the relationship between SMA and SMV18. Aplasia and hypoplasia of the uncinate process have been described in patients with INR19. Understanding the anatomical variants in the context of INR helps surgical planning, as in the case published by Pagkratis in a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with INR20.

Patients with acute symptoms and evidence of volvulus require immediate surgical intervention18. Treatment of people with rotational anomalies without volvulus is controversial and often dictated by symptoms8. The presence of vague abdominal discomfort in a patient with a known rotational anomaly justifies laparotomy8. Choosing a non-surgical treatment route requires extensive knowledge of subtle signs of complications by medical providers8. Appendectomy is recommended for all patients undergoing laparotomy8,13. A study by Brungard et al. showed that if an appendectomy is performed, it has a minimal impact on postoperative results and could be considered safe while the malrotation is surgically corrected21.

Conclusions

INR is a rare pathology because patients can remain asymptomatic until adulthood, making it an incidental diagnosis in many cases. Knowing the characteristics of INR is relevant in the context of acute abdomen, taking into account the possibility of volvulus and intestinal obstruction inherent to this entity and in scenarios such as appendicitis, where its clinical manifestation may change depending on its location. Approaching the imaging findings of this pathology can help with early diagnosis and reduce the risk of complications.

text in

text in