INTRODUCTION

All population groups often present different types of dentoskeletal alterations, affecting both men and women and individuals of all ages.1)(2 Several studies have been conducted in the Colombian population, such as the ones by Thilander et al,3) Franco et al4 Melrose et al,5) Botero et al,6 Plazas et al,7) and Mafla et al,8) to determine the prevalence of malocclusions, finding out a greater presence of class I malocclusion along with dental crowding, followed by class II and class III malocclusions.9) On the other hand, the 1999 Estudio Nacional de Salud Bucal (ENSAB III) conducted a comprehensive analysis of the occlusal alterations occurring in all three space planes, indicating the need for therapeutic intervention on them.10) Orthodontic treatment seeks to correct different types of malocclusion by means of mechanical devices that transmit forces to dental structures and the tissues that support them.11)(12)(13)(14 Once a treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances is completed, it is necessary to initiate a retention phase that may range from 6 to 12 months, with either fixed or removable devices aimed at keeping teeth in place, preserving the achieved results and allowing the reorganization of periodontal and gingival tissues once malocclusions have been corrected.15)(16)(17)(18)(19)(20)(21)(22)(23)(24) Recurrence occurs in a high percentage of cases treated with orthodontics, with individual variations due to factors such as craniofacial growth, tooth development, functional habits and muscle function; it is therefore necessary to know the individual dental and skeletal development in order to accurately plan the right type and post-orthodontic retention time for each patient.25)(26)(27)(28)(29)(30)(31)(32)(33)(34)(35) In the clinical practice in Colombia and many other countries, the Hawley retainers have been widely used and researched 36)(37)(38)(39(40)(41) and for some years now the implementation of Essix retainers has been significantly increasing.42)(43)(44)(45)(46)(47)(48)(49) They are widely accepted by patients due to their aesthetic appearance, low cost, and the short manufacturing time needed.38) Some studies, like those by Lindauer and Shoff (1988),40) Sauget et al (1997),41) Rowland et al (2007),38) Dincer and Isik (2010),42) and Barlin et al (2011),43 have assessed the clinical effectiveness and stability of these types of retainers.43)(44)(45)(46)(47)(48)(49)(50 Currently there are no reported studies evaluating and comparing these devices in Colombia, and therefore orthodontists lack academic elements beyond aesthetics or patient acceptance to help them make the best choice regarding which retainer type to use.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the stability of dental and occlusal position in all three planes of space during retention treatment in a six-months period with two types of retainers in individuals who completed orthodontic intervention at the Universidad de Antioquia School of Dentistry, Universidad CES, and private practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was an experimental study in the form of a randomized non-masked clinical trial in 47 subjects aged 15 to 45 years with stable growth who completed orthodontic treatment and started retention phase. Patients were randomly selected by means of a random allocation table in Epidat; 25 individuals were treated with Essix retainer and 22 with Hawley plate. They all accepted voluntary participation by signing an informed consent. Subjects had no history of periodontal disease, congenital craniofacial malformations, oral habits or history of previous orthodontic treatment or open bite. Retainers were fabricated according to the requirements established by the authors, Sheridan 48) and Hawley 50) (Figure 1 and Figure2).

The cephalometric analysis was performed before installing retainers (T1) and six months afterwards (T2), when the sagittal position was evaluated. Angles: UCI/SN (upper central incisor/Nasion), UCI/FH (upper central incisor/Frankfort Horizontal plane), UCI/PP (upper central incisor/Palatal Plane), LCI/MP (lower central incisor/mandibular plane). Distance: UCI/AP (upper central incisor/Pogonion A) ICI/AP (lower central incisor/Pogonion A), and interincisal and vertical angle (UCI/PP distance (upper central incisor/palatal plane), upper first molar/PP), LCI/PM (lower central incisor/mandibular plane), first lower molar/PM); In addition, the interincisal angle was measured.

Also, monthly clinical evaluations were conducted during six months to evaluate right and left canine relationship, right and left molar relationship, horizontal and vertical overbite, and the presence of anterior and posterior open bite.

To analyze changes in tooth position, a couple of models of each individual were processed using a scanner and the Ortho Insight® software at T1 and T2, registering the occlusal sides of upper and lower arches to obtain digitalized images that allowed evaluating tooth rotation by measuring the angle formed by a bisector point of the axis of rotation of the model established by the software, as well as the mesial and distal point of contact of each tooth, determining the rotation of central and lateral incisors, canine, first and second premolars and first molar of each hemiarch (Figure 3). These images also evaluated the transverse plane with variables such as arch shape, intercanine distance, interpremolar distance and intermolar distance.

All radiographic and photographic procedures and their readings were performed by the same operator and team, all of whom were previously standardized.

Figure 3 Digitalized image of the upper plaster model showing the bisector point of the rotation axis of the model established by the software, as well as each tooth’s mesial and distal contact points, determining the angle of tooth rotation

To have an approximate concept of tooth stability, this was defined when the angulation difference of each tooth in the software was lower than 1.5° between T1 and T2; when a greater difference in angle was found, it was classified as no tooth stability.

Each arch was subsequently divided into anterior sector (canine to canine) and posterior sector (first premolar to first molar) adding up the stability of each tooth per sector, defining as stability of each tooth group when four teeth or more had tooth stability, and no stability when three teeth or more of each sector had no tooth stability.

Before starting this research project, and as a means of assessing the instruments, a pilot test was conducted with a sample of five patients who were subjected to the entire planned protocol. The results of this test were taken into account in the sample, since the concordance tests (Kappa) between two observers yielded results of 97%.

The present study was a joint effort between Universidad de Antioquia and Universidad CES. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the latter and was registered in the clinical trials page to ensure compliance with ethical and clinical standards, while guaranteeing the absence of conflicts of interest.

Statistical analysis. The statistical analysis was performed on PAWS 18, including a univariate and a bivariate phase. A univariate analysis was used for the socio-demographic variables (age, gender, socioeconomic level, and origin), including average, median, mode, and standard deviation for quantitative variables, and proportions for the qualitative ones, plus corresponding tables and graphics. For the bivariate analysis, normality distribution tests (Shapiro-Wilk) of quantitative variables in qualitative categories (p < 0.05) led to non-parametric statistical tests to compare by treatment group or by treatment times within each group (U-Mann Whitney or Wilcoxon, respectively); the used parametric tests (p > 0.05) were Student-t and paired-t, respectively. In addition, an analysis was conducted by means of the McNemar test to establish differences in proportions in terms of occlusion before and after treatment in each group, and the Chi-square test was used to establish the relationship among independent qualitative variables. A 5% statistical significance level was used.

RESULTS

The average age of patients in this study was 21.85 years; 57.4% were females, and most patients came from middle socioeconomic levels (59.6%). Concerning origin, 48.9% of the studied subjects came from private practice, 46.8% from Universidad de Antioquia, and 4.3% from Universidad CES. 10.6% of subjects were in stage CS5 of cervical maturation and 89.4% in stage CS6, guaranteeing growth stability.

As for tooth position, tooth rotations in the Essix group showed statistically significant differences between T1 and T2 in upper right lateral incisor (p = 0.025), upper right canine (p = 0.037), lower right canine (p = 0.017), and second lower right premolar (p = 0.036). On the other hand, the Hawley group teeth that showed these differences were: upper right lateral incisor (p = 0.001), lower left lateral incisor (p = 0.028) and first left lower premolar (p = 0.031).

In comparing the two groups there were statistically significant differences in terms of position of the left upper first molar in T2 (p = 0.025).

No statistically significant differences were found in the sagittal plane between T1 and T2 within each group or in comparing the two groups.

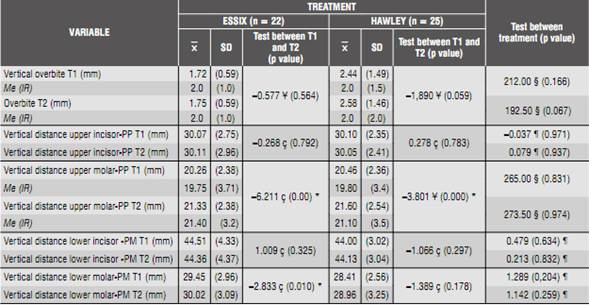

As for the vertical plane, statistically significant differences were found in terms of upper molar-PP distance (palatal plane) in both groups between T1 and T2 (p = 0.000) and in lower molar-MP distance (mandibular plane) in the group treated with Essix retainer (p = 0.010) (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of subjects according to vertical characteristics

I.R.: Interquartile range; * p value < 0.05; § Mann-Whitney U test; ¶ Student t-test; ç paired Student t test; ¥ Wilcoxon test

Statistically significant differences were identified in the transversal plane in terms of the upper intercanine distance in the Hawley group between T1 and T2 (p = 0.02) (Table 2).

Table 2 Distribution of subjects according to transversal characteristics

I.R.: Interquartile range; * p value < 0.05; § Mann-Whitney U test; ¶ Student t-test; ç paired Student t test; ¥ Wilcoxon test

On the other hand, the arch shape of intervened subjects remained stable during the evaluation time in both treatment groups.

In evaluating change in canine and molar relationship, there was stability within each group; however, there were statistically significant differences when comparing both groups in terms of right molar ratio in T1 when it was class II (p = 0.02), and left molar relationship in T1 and T2 when it was class III (p = 0.026) (Table 3).

Table 3 Distribution of subjects according to canine and molar relationship

R right can: right canine relationship; R left can: left canine relationship; R right mol: right molar relationship; R left mol: left molar relationship; Me: median; I.R.: interquartile range; X media; (SD): standard deviation; * p value < 0,05; § Mann-Whitney U test; ¥ Wilcoxon test; ¶ Student t-test; CONS: constant; ç paired Student t-test; there is no calculation: the difference cannot be established

No signs of anterior or posterior open bite were found during the six-month evaluation period in either group.

Concerning stability in the evaluated dental segments, there were no statistically significant differences between both treatment groups. However, from the clinical point of view, the impact measurements indicate that the upper and lower anterior segments and the upper posterior segment were more stable during the six months of treatment within the Hawley retention group, while the lower posterior sector was more stable in the Essix group (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Stability of the results of orthodontic treatment has been a topic of interest in this specialty. The problem of keeping teeth in their new position following the orthodontic process was recognized by Kingsley in 1880.51) Later, Angle said that, “as the tendency of teeth that have been moved into occlusion is to return to their former malpositions, the main principle to be considered is to antagonize the movement of the teeth only in the direction of their tendencies”.52

In terms of time needed to retain treatment results, Angle offered an additional device, stating that retention time varies depending on patient’s age, achieved occlusion, causes of malocclusion, achieved tooth movements, length of cusps, tissues health, among other variables, and that retention time can range from a few days to a year or more.53)(54

Behrents points out that full stability does not exist in the craniofacial skeleton or in dentition following treatment, and that recurrence in the sagittal, vertical, or transversal dimensions depends on patient’s growth patterns rather than on the orthodontic treatment itself.55 Taking these statements into account, this study only included patients whose active pubertal growth was absent, by determining the stage of cervical maturation.34 However, Björk in 1955 showed the high variability of normal facial growth,53) and several authors point out post-orthodontic facial growth during adult life as an important factor to be considered in the etiology of orthodontic recurrence,53)(54 which could explain some types of recurrence in some individuals.

As for changes found in terms of position of each tooth’s longitudinal axis, analyzed from the first molar on one side to the first molar on the other, in both arches there were statistically significant differences during the six-month evaluation period for teeth 12, 13, 43 and 45 in the Essix group, and for 12, 32 and 34 in the Hawley group. While this study analyzed changes in the rotational axis of each tooth, some studies have compared changes in the position of longitudinal axis by means of Little’s irregularity index; 26) however, several studies have reported more irregularities with the Hawley plate than with the Essix retainer. Rowland et al 38) observed greater irregularity in the upper and lower incisive zone with Hawley plates than with Essix retainers, and Lindauer and Shoff 40) reported more irregularity in the upper incisive area with Hawley plate in a six-month evaluation.

Some authors, like Jäderberg et al 56) and Thickett and Power,46) found no statistically significant differences in incisive irregularity between the Essix retainer and the Hawley plate.

Gill et al 48) reported an increase in Little’s irregularity index in two compared retainers-Essix and a fixed retainer- after six months of evaluation. This agrees with the present study, since although the resulting tooth irregularity could not be grouped by areas, it is noticeable that both groups presented changes in tooth positions, which can be explained by the periodontal remodeling and the reorganization of periodontal ligament as a decisive control factor in dental position balance.37

In the sagittal plane, which was clinically and radiographically evaluated, no statistically significant differences were found in dental and occlusal stability. It might be that the evaluation time is not sufficient to gather important findings from the radiographic point of view. However, the clinical evaluation of overjet did not yield differences either, allowing to conclude that at this plane both retainers have the same clinical control. These results agree with authors such as Rowland et al,38) Lindauer and Shoff,40) Jäderberg et al,56) and Tynelius et al,47 who did not find significant differences in overjet between the two retainers during the evaluation period. This control of the two retainer types can be explained by the physical barrier created by the vestibular arch on the Hawley plate and the acrylic in the Essix retainer, in addition to biological barriers, such as the upper and lower lips and perioral muscles, which may be involved in containing this plane.

As for the vertical plane, statistically significant differences were found in terms of distance between the upper first molar and the palatal plane in both groups, and in vertical distance of the first lower molar to the mandibular plane in the Essix group; however, the other vertical variables did not show significant changes. Nevertheless, studies such as the ones by Tsai,44 who reports that long-term use of the Essix retainer produces anterior open bite, and Gill et al,48) who contradicts this last assertion pointing out that there is no relationship between the use of Essix retainer and open bite, as well as other authors, who found no overbite changes when evaluating subjects using both retainer types,38)(40)(41)(42)(43)(44)(45) allow to conclude that, although changes to the molars were found in both treatment groups, this is not sufficient basis to assert that the vertical changes experienced by molars are caused by a tendency to anterior open bite, since anterior and posterior open bite were absent in all the evaluated subjects in both treated groups. These vertical changes in molars might result from the periodontal remodeling and the biological occlusal adjustment naturally occurring after orthodontic treatment.37)(47)(48 Nevertheless, none of the two retainers may be considered as an etiological factor for post-orthodontic open bite, since molar change occurred with the two devices; in addition, neither group showed open bite.

In the transverse plane, there were statistically significant differences between the evaluation times in terms of upper intercanine distance in the group treated with Hawley plate. This finding disagrees with reports by other authors such as Thickett and Power,46) Barlin et al,43) Tynelius et al,47) Tibbets,45) and Rowland et al,38) who found no statistically significant differences between intercanine distance and intermolar distance during the evaluation period for the two types of retainers. One possible explanation for the change in upper intercanine distance is the lack of transversal control by the Hawley retainer due to the clasp located on the interproximal contact between canine and first premolar, which can create transverse instability of this tooth. However, this clasp is also placed on the lower arch in the same location, but one part of the vestibular arch of the lower plate may have control over the vestibular surface of the lower canine; this may explain the absence of changes in lower intercanine distance.

In terms of molar and canine relationships, no statistically significant differences were found in both retention groups; however, there were important changes from the clinical point of view. For instance, during the six-month evaluation period the canine relationship remained more stable than the molar relationship. From the point of view of changes quantification in these sagittal relationships, there were statistically significant differences between the treatment groups in terms of right molar relationship at T1 (baseline), when the molar relationship on that side was class II; however, at T2, or six months of evaluation, these differences disappeared, which can be explained by the changes occurring in the vertical plane with the upper molar-PP distance and the lower molar-PM distance, which may have effects on other space planes, representing a slight inclination that may have resulted in differences in these characteristics of sagittal adaptation.

After defining tooth stability based on the amount of rotation changes in each tooth between the two evaluation times in this study, no statistically significant differences were found in tooth stability between the two retention devices; however, as part of the epidemiological contributions, some impact measures were defined to help orthodontics specialists make decisions to offer more effective retention treatments. And in this process, it was found out that Hawley plate was more effective for anterosuperior, posterosuperior, and anteroinferior stability, whereas the Essix retainer was more effective in terms of posteroinferior stability. It is important to remember though that these assertions are the result of an experiment, and that changes in the limits of quantification in the difference that defines tooth stability or lack of it can create changes of these relationships. It is also clear that, in terms of tooth stability, there are no statistically significant differences between the two retainers.

CONCLUSIONS

In comparing the effectiveness of the Essix retainer against the Hawley plate, there were no differences in sagittal plane, arch shape, or vertical and overjet, nor signs of anterior and posterior open bite during the six-month evaluation period.

The vertical control of both retainers is similar for the first upper molar, while the Hawley retainer has better vertical control on the first lower molar. However, the differences found in this plane did not have anything to do with the appearance of post-orthodontic open bites with the Essix retainer.

In the transverse plane, the control offered by the Essix retainer for the upper arch is more stable than that of the Hawley plate over a period of six months.

Since isolated tooth rotations were found in each group, one may conclude that the use of both retainers can be complementary in retention treatments.

While some isolated statistically significant differences were found, they are not sufficient to indicate differences in the effectiveness of dental and occlusal stability between the two retention devices under study.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Studies comparing these retainer types are recommended, including monitoring for a longer period of time to confirm that the lack of differences found in this study is not time dependent.

Given the importance of choosing the best retainer to ensure stability in the post-orthodontic patient, it is essential to take into account that such selection should be based on the characteristics of each patient and on evidence rather than on the orthodontist’s clinical preference.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To the IMAX medical diagnosis center for taking and processing the diagnostic aids for this study; to Asesorías Técnicas en Ortodoncia (ATO) for manufacturing the retainers; to Universidad CES for its academic support; to Universidad CES Research Department for funding this project and for its support in collecting the sample, and to Universidad de Antioquia for its operational and academic support.

text in

text in