Introduction

Knowledge is part of the very existence of society and the “question of knowledge” has been a constant in the various academic disciplines, not only in pedagogy, but also in psychology, sociology . . . and the mother of the sciences, philosophy. Such is the case that the term composed of philosophy, translates as “love of wisdom”, which tries to offer an explanation for the disparity that occurs in the apparent order of things and reality itself. It is not the subject of this research paper to show “clear predominance of reason” but giving a big jump, placing the issue in a much closer and pragmatic point of reality, and alerting the awareness of the deep and latest implications that the analysis of any reality, also knowledge, can reach.

The breadth of the concept “knowledge” is very high, but in an explanatory classification (Berrocal Berrocal & Pereda Marín, 2001); this may be, in its classical sense, a storage of knowledge with a degree of connection; a set of data as raw material for any decision; or information that runs through the messages from a sender. But none of these contents would be enough, and would not limit the content of knowledge. For the same authors (2001: 644), when it comes to knowledge we mean a learning process through which a person is able to do something he could not do, or can do better than they did before. (. . .). The “knowledge” is something more: it is A set of structured information and experiences, values and contextual information that let you change the modus operandi of the receiver. knowledge, therefore, include both “knowledge” as the “know-how” and the “know to be”, included in the concept of competence; that is, the theoretical knowledge on a given subject, applying them to solving the practical problems of labor, and the attitudes that facilitate a behavior in line with the values and culture of the organization.

With this definition, we can connect with the term competence. Olaz (2011) comprises three dimensions: the knowledge, skills and abilities.

Following the author, in the first dimension, the subject of analysis in our work is related to knowledge, regulated or unregulated, available to individuals from a theoretical and practical perspective. In short, knowledge is a constitutive element of the skills necessary for their development.

The social role of knowledge

From the above brief introduction, it is easy to predict the component “social” of knowledge, or in other words, the relationship between social processes and knowledge, whose analysis is developed by the sociology of knowledge. As stated by Lamo de Espinosa (1993-94: 21) the essence of the sociology of knowledge is to claim that the knowledge emerge in particular and concrete social conditions, that is, the subject of knowledge is empirical and historical.

In Vera (2012), despite the diversity of theoretical and methodological approaches for the analysis of the relationship between knowledge and social structure, there is a com mon denominator in that diversity, consisting in consider knowledge as a social product, otherwise the opposite of a self-sufficient reality or the creation of isolated individuals. The social component of knowledge implies to consider social relations and structures in which people are immersed, as well as the material and intellectual resources that societies offer and allowing them to organize their thinking.

There is another interesting element to consider in this area and it is the “active” character of knowledge. Mannheim (1987) argues that the nature of human knowledge is fundamentally active, not passive. Knowing is an activity of collective historical subject in view of interests which have an “instrumental value”.

Also from other disciplines, it has emphasized the active character of knowledge. In Hernandez (2008), citing Inhelder and Piaget (1955), the individuals feel the need to “build” their own knowledge. This is built through experience, generating mindsets that are changing, expanding and becoming more sophisticated. From a complementary level, Kolb (1984) puts experiential learning, as a model that involves a process whereby knowledge through experience is created, although this by itself is not enough, and must be analyzed through the reflection. Also, that knowledge is a transformation process that is continually creating and powered by the same relevance in everyday life.

Advancing through the levels of the analysis that are steps in this work, it is interesting at this point to refer to an article in the American Economic Review, XXV in 1945 by Friedrich A. von Hayek, later published in issue 80 of the REIS in 1997. In the article, titled as clearly as suggestive “The Use of Knowledge in Society”, the author wondered what problem we intend to solve when we tried to establish “a” rational economic order? To raise it (1997: 2) the economic problem of society is not simply about how to assign resources “given” such-understanding by those “given” to A single mind that after examination solves the problem raised by these “data”. It is rather the problem of how to ensure the best use of resources known to any members of a society to achieve ends whose relative importance only they know. Or, in short, is the problem of the use of A knowledge that is not given to anyone in its totality. For the author, beyond scientific knowledge, identified by stick based on general rules, there is a significant set of knowledge comprising knowledge of specific situational and temporary circumstances which occur in the practice of all individuals whose consideration is also required for the capacity to adapt to change, and for whose clarifying example indicates how much we have to learn for the exercise of a professional activity specific once completed the theoretical learning.

Just add another contribution to the analysis of the competence dimension of knowledge on female entrepreneurship from a social level, and this could not be other than the inclusion of a gender perspective of the labor and professional process. Wood (1987) stresses that qualifications are not socially neutral; there is a social construction process of the qualification that leads to their social labeling. This labeling has led in many cases the undervaluation of certain capacities of women. For the author, the roots of this process are on the TACIT knowledge developed through individual experience, but learned in the socialization process.

All these theoretical elements have been subject to important academic arguments, although here a burst mode that allows us to limit a first set of elements for the analysis of the discourse on the competence dimension of knowledge on female entrepreneurship, and on which we will focus later has been considered.

Knowledge and skills development for women entrepreneurship

There seems no doubt that skills have, among their constituents, knowledge. Grau Gumbau and Agut Nieto (2001), in a synthesis about definitions of competence based on their components, collected that the knowledge is present in the contributions of Quinn et al. (1990); Ulrich, Brockbank, Yeung, and Lake (1995); Arnold and McKenzie (1992); Olabarrieta (1998); Boyatzis (1992); Spencer and Spencer (1993); Levy-Leboyer (1997) and Peiró (1999), thus coinciding with the thesis used as the basis for our research and proposed by Olaz (2011), although they all can diverge in other elements.

A reference is then required, at this point, with which we approach the level of knowledge of women entrepreneurs. In this sense, the most comprehensive information is offered by the GEM Project (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), which analyzes entrepreneurial activity in more than 70 countries. In a working paper prepared by the research team1 on the profile of women entrepreneurs nationwide, it shows that they have similar characteristics as compared to men, and only produced a significant difference with regard to the education level, where women entrepreneurs have a slightly higher level than men, so that entrepreneurs with university studies level reached 38.4%, compared 32.3% among men, in Spain in 2012. In a study of environment factors with influence in female entrepreneurship, Alvarez, Noguera, and Urban (2012) hypothesized that training has a positive effect on the probability of women undertake. After the contrast used a statistical hypothesis about the GEM Project data, they cannot conclude that the hypothesis is true, or in other words, training discriminating variable is not allowing that probability, perhaps an effect of sample composition. Moreover, the authors collected numerous investigations that reflect the positive effect of the training on female entrepreneurship and also those who cannot conclude that relationship. It seems, therefore, that there is difficulty in using training as an explanatory variable, and therefore as a variable of approach and knowledge of women entrepreneurs in our case.

Other studies have also incorporated the qualitative perspective; they have helped to introduce more elements of analysis. In the case of Jiménez Moreno (2011), who confirmed the sample of women interviewed, a high educational level in the same, however, does not prevent them run into some obstacles to the development of its human capital. Among these are the lack of time outside of working hours, breaks due to family responsibilities, especially its lack of specific human capital in entrepreneurship, trying to overcome with the realization of training actions. Another important conclusion of his research is on LEARNING, which admits that it is an active process in which entrepreneurs seem to develop through learning “of double-cycle”, that is, reflecting on the successes and mistakes. It emphasizes the (self) LEARNING, as essential and an ongoing challenge based on previous knowledge acquired by women entrepreneurs.

In short, it seems that the analysis of the jurisdictional dimension of female entrepreneurship is conditioned at its source by educational level and the knowledge that women entrepreneurs have from the start, as well as what might be called their own learning processes.

Methodological aspects and empirical analysis

The objective of this work is framed in one from the most general level, that tries to analyze which jurisdictional issues have female entrepreneurship, that is, analyzing the competence profile of female entrepreneurs, the detection of peculiarities and their relationship with specific forms of entrepreneurship. In this line, we try to advance in the analysis of the role of knowledge in the entrepreneurial activity of women.

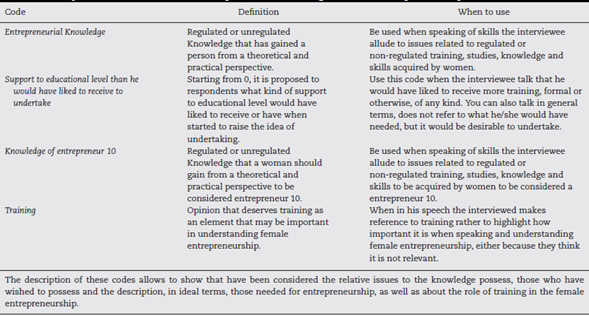

The empirical material, of a qualitative nature, was obtained through interviews, whose methodological procedure is described at the beginning of this monograph. The analysis of the material has been supported by the use of Atlas.ti program, which has provided us with a first descriptive information processing and subsequent analysis of discourse as social information2. It should be remembered, given their importance in our object of analysis, as regard the profile of the women interviewed, that the educational level they have is medium-high and high, the result that most women entrepreneurs have this feature, such and as discussed above. What roles do knowledge have on female entrepreneurship, considering these not only as a component of competence profile, but also as holistic categories, socially integrated? To answer this question we have considered the information in the following codes, built on the transcription of the interviews conducted (see Table 1).

Table 1 Analysis codes associated with the speech on “knowledge of female entrepreneurship”.

Source: Authors.

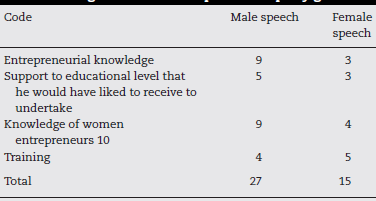

A descriptive analysis, based on the frequency of the codes associated with our objective, highlights a significant difference in the presence of the same between female and male speech (remember that the same number of interviews were conducted in women and men). However, the frequencies (see Table 2) are higher in men codes related to the knowledge they have, they would like to receive or to have an ideal entrepreneur. It is not so for those relating to training. Of special note is the presence in the men’s speech referred to the “entrepreneurial knowledge” and the reference to “knowledge of women entrepreneurs 10”. But, that is not the case in the rest of the codes related to training, as it is previously warned. In any case, the male discourse, the aspects related to knowledge, has a greater presence and visibility than in the case of women.

Table 2 The frequency of use of codes in the discourse on “knowledge of female entrepreneurship” by gender.

Source: Authors.

The differences on entrepreneurial knowledge are not limited on a quantitative level. The increased presence of this aspect in men, it seems that carries an association with the importance given to the knowledge acquired through a process of formal training by gender. Women have a well-defined vision of knowledge that favor or are required to undertake and can be summarized as: “business”, “market” and “competition”. Also associated with this knowledge, place value on the process of (self) LEARNING to which we referred in our review of theoretical elements, so that emphasize informal training versus regulated, acquired in “everyday”, giving significance in the process to the specific situational and temporary circumstances that alluded Hayek (1997). A formal education, developed under the protection of the education system, mainly university, gives it a role of “facilitator” of the skills needed for further learning not regulated. In short, they show a more independent and autonomous attitude to this process.

An entrepreneurial woman, who wants to undertake, should form particularly in the business to be undertaken. (. . .). Training in business, know the competition, know the market . . . it is essential (E1-Women).

Right now they ask me what the university has given to me and I’ll tell you to give me the ability to work, to give me a foundation and a molding head, that’s it. Learn what I’ve learned from day to day, it is when you learn (E4-Women).

For its part, the speech of men saved nuances of difference with respect to women. In terms of knowledge, it highlights the need to have “vision” or “an idea” of business, with a more strategic and projection character. There is also a notable trend to highlight the value of formal training as a source of knowledge, especially in the higher levels of education, which does not prevent to deem necessary the practical learning from the activity, but never refer to it as a process of (self) learning.

If you are a businesswoman-entrepreneur must have a breathtaking view of business (E7-Man).

Today, both men and women I consider them more than ever able to carry out any initiative, and indeed in the universities I’d say there are more women than men today who are preparing to take and carry out this initiative to fruition. (E8-Man).

The observed differences in male and female speech in relation to the entrepreneurial knowledge correlate with those that can be observed with regard to training support that he would have liked to receive to undertake. In this sense, the speech of women entrepreneurs can be summarized in the “global perspective” to “local application”. Indeed, the discourse of women in this point makes reference to the knowledge of languages, experience of international mobility, foreign trade and to the recurrent expression “know everything”. While, it does not stop there, this adds the need for guardianship or specific advice for the implementation of the business idea. In this case, the relationship is palpable of the social processes, such as globalization, the knowledge and thinking of society, leading to new morphologies of thought that need nurturing of new knowledge.

The languages, in which is essential to control English, and go out, training abroad, if not the entire career only a part because the idea of training abroad and to break through is essential (E5 Woman).

Today, an entrepreneur has to know everything. I will not say that you have to be an accountant but you need to know how to tell to the accountant where to go. You must have some knowledge, full preparation, because you can hire people who are very good. . . (. . .) So you have your knowledge but I want this done my way . . . (E2-Women).

For its part, the male discourse about the support that wished in the training level for undertaking can be described as more “traditional”. Again, referring again, with a large degree of consensus, on advice or training related to the sector in which you want to undertake and the business idea, well as the added value of having a university education. It must be remembered that the educational level of men is somewhat lower than women, giving greater proportion of university entrepreneurs. Despite these differences in educational level they are relatively significant and they seem to condition the discourse between both genders.

Is needed in the business that you are going to undertake, that you have the knowledge in that business or in the activity that is going to undertake (E7-Man).

Well I sure would have acquired that university education, it is said in an economic career, it could be, and that’s the aspect I complement in my particular case of what I have (. . .) At university I think there are more women than men studying, which have that training support (E8-Man).

However, the identified differences in the discourse about the knowledge of the entrepreneur and about the support of the educational level that they would have liked to receive seem to dissipate when referring to the knowledge of a great entrepreneur. In this case, both discourses converge in a compact message, which does not focus on both the content and on the outcome of knowledge, that is, an ideal entrepreneur is not characterized by a high degree of knowledge on certain issues, but by the fact that his “vast knowledge” would provide it with a “preparation” (capacity) to undertake and forge clear ideas about what they want to do.

Well you have sufficient preparation and enough talent to lead and successfully carry out any project to be put forward (E5-Women).

And it also has the knowledge, or know to surround himself with people who have knowledge, to develop this idea on an ongoing basis over time (E10-Man).

All must be accompanied by training behind; we are talking about a person who has their studies, training, and then an idea and some approaches (E7-Man).

A person who has an idea of what he wants to do, that has very clear ideas, and is prepared (. . .) I think it does, which is important, but it is the way to reach the end result that is the other (E9-Man).

Also present, in both speeches, is the need for a permanent active learning. This issue also would connect with the new social morphology of thought, rightly warns in the subject of permanent change processes and the need, therefore, for lifelong learning to deal with them.

Truly, it is also important to try to improve in knowledge of new things that can be implemented in the company . . . (E2-Women).

Having a very good training and that is continuously with the continuous training (E8-Man).

The synchrony in the speech of women and men entrepreneurs remains, in a high degree, when the importance of training for entrepreneurship is all about. Training is an intrinsic activity to entrepreneurial activity and it is based on building and maintaining the entrepreneurial project. Moreover, and provided that the purpose is given, it is understood to a significant extent, as a means of acquiring any kind of knowledge, including personal self knowledge, to be able to apply to the generated business. The nuance of difference is given in the strength of the message, that is, women have a speech reflecting a greater force when identifying the benefits of training in entrepreneurship.

I always think that training and education as applied to what is known, what has been lived, what they have taught you or you have the idea of how I will assemble this and where I have to go. But training is basic for all this (E7-Man).

The first is the training and in terms of training I do not mean. . . well, yes, but not only formation of “well, I will make an accounting course.” No, no, but to skills courses, of abilities (. . .) what is the growth staff, focused to the company, of course, but growth staff (E4-Mujer).

Without training you can not have security (. . .) but obviously the more training you have, even in a small area, you have more confidence in what you’re doing and your knowing (E3-Women).

Conclusions

The purpose of this work came represented by the identification of differences in the components of the competence profile of female entrepreneurs, in this case, in the dimension of theoretical and practical knowledge. To do this, we had to start from the premise that these, and their processes of associates learning, are mediated in its entirety by the social, since knowledge involves an active process on the part of the subjects inserted at specific social processes.

Trying to answer the purpose of the work and the question that was formulated on what role is played by the women entrepreneurship knowledge, we can conclude that there are indications pointing to a particular configuration of the same in men and in women entrepreneurs, resulting mainly from the two conditions to which we referred in this text, that is, the starting level of education and learning processes.

Thus, we find that in the speech of women entrepreneurs, it is a clearer identification of the skills needed for entrepreneurship (remember “business”, “market”, “competition”, “global vision”, “languages”...) and we could link a learning process that is also different. Perhaps the greater presence of women in the formal education system, with a high proportion of university women entrepreneurs, feeds the perception of learning opportunities through other processes and, especially, in the daily practice. This, and shaping a circle that feeds back, will facilitate the identification of more knowledge required and, therefore, what is the best place to acquire them. This does not imply, in any case, that this circle is not present in men, but it could be more intense in the case of women.

The pragmatic aspect of men entrepreneurs is more focused on other issues, not only based on the practical learning, to which they refer more often but in general terms, but also to formal education and specific knowledge of the sector and the activity to develop. This would provide significance to the contribution collected from Hayek (1997) while the specific situational and temporary circumstances approach known resources, assuming they do not represent the totality of knowledge.

This result would be consistent with the fact that there are fewer discursive differences referring to the ideal entrepreneur or the importance of training in entrepreneurship, since the valuation of these issues does not involve consideration of the process, only the result or final paper that represents.

Therefore, the construction, both individual and social, of knowledge we referred to in this work, is what makes the difference between gender.