Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Internacional

Print version ISSN 0121-5612

colomb.int. no.63 Bogotá Jan./June 2006

URBAN RESISTANCE, to Neoliberal Democracy in Latin America

Susan Eckstein1

1Profesora de sociología en la Universidad de Boston. Fue presidente de la Asociación de Estudios Latinoamericanos (LASA) y ha escrito más de seis docenas de artículos sobre America Latina.

Resumen

Los procesos de democratización en América Latina restauraron los derechos laborales y políticos que habían sido negados durante los gobiernos militares que tuvieron lugar entre las décadas de los sesenta y ochenta. El aumento de la subordinación a las fuerzas del mercado, menos constreñidas por barreras institucionales bajo el modelo neoliberal, debilitó, de hecho, la habilidad de los trabajadores para utilizar sus derechos recién restaurados para el mejoramiento de sus condiciones laborales. Este artículo describe cómo y explica por qué las protestas contra las injusticias económicas percibidas bajo estas circunstancias se han trasladado, en las ciudades de toda la región, de la producción al consumo; y en este dominio del consumo, de los reclamos pro-activos en favor de acceso a vivienda hacia protestas defensivas en contra de iniciativas estatales tendientes a aumentar el costo de los alimentos y los servicios urbanos, y también hacia la configuración de movimientos de solidaridad que desde los países más ricos amenazan a las empresas que explotan a los trabajadores latinoamericanos con boicots de consumidores.

Palabras clave: protesta, movimientos sociales, neoliberalismo, distensión urbana, crimen.

Abstract

Redemocratization across Latin America restored labor and political rights denied under the military governments in the 1960s through the 1980s. Increased subjugation to global market forces, less fettered by institutional barriers under neoliberalism than under import substitution has, however, weakened, de facto while not de jure, the ability of laborers to deploy their restored rights to improve conditions at work. The article describes how and explains why protests against perceived economic injustices under the circumstances have shifted in cities across the region from the point of production to the point of consumption, and within the arena of consumption from pro-active claims for affordable housing to defensive protests against state-backed increases in the cost of food and urban services and to solidarity movements in rich countries that threaten businesses that exploit Latin American workers with consumer boycotts.

Keywords: protest, social movements, neoliberalism, urban strife, crime.

recibido 20/04/06, aprobado 30/05/06

Introduction

The new millennium began with the triumph of democracy over dictatorship and the institutionalization of market economies minimally encumbered by interventionist states. Many believed that in Latin America these changes would usher in more just societies and resolve problems created or not resolved by import substitution and the military governments that dominated the region between the 1960s and 1980s. Neoliberal reforms were to improve the performance of economies, democratization to open up channels for majority rule and representation and, in turn, for the selection of rulers responsive to the interests and concerns of the citizenry. At the same time, democratization, in principle, made it less risky for the dissatisfied to organize collectively to defend concerns formal institutional arrangements left unaddressed.

The purpose of this essay is substantive: to synthesize how and explain why the Latin American repertoire of economic struggles has shifted under democratic neoliberalism from work sites both to neighborhoods and overseas to consumer solidarity movements, and from protests to improve work-linked conditions to efforts to lower costs of consumption and to make cities more livable. The shift occurred as the work force's earning and purchasing power deteriorated when subjugated to market forces more global in scope and more pernicious in effect than under import substitution, even as democratization formerly restored labor and other citizenship rights. Globalization has weakened labor's bargaining power relative to capital's at the same time that privatizations and subsidy cutbacks have driven up the cost of living.The mobilizations described below are illustrative. They are not exhaustive, and include only those urban-based2.

Struggles for Work-Based Rights

Work based movements are shaped by the political-economic context in which laborers lives are embedded. In this vein, during the import substitution era Latin American workers were somewhat shielded from the full effects of global market forces because governments imposed trade barriers and industrial production was largely domestically oriented. Labor accordingly could exert pressure on capital when possessing skills in short supply. Skilled workers won rights to organize, to protect and advance their interests, and to strike, namely, to withdraw collectively their labor power as a weapon to defend their interests. They thereby won rights to a minimum wage, to fringe benefits, to restrictions on the length of the work day, and to job security, formalized in labor codes. Unions provided an organizational nexus whereby workers with shared interests and concerns bonded and shared ideas on how collectively they could press for improved work conditions (Eckstein and Wickham-Crowley 2003c).

Workers in the public sector won similar rights. And because the state's role in the economy expanded under import substitution, as both state-owned enterprises and state social service provisioning expanded, the labor force covered by labor laws came to include middle class employees. Even more than workers in the private sector, those in the public sector were shielded from the vagaries of the market, which strengthened their bargaining power.

The range of rights organized workers in Latin America won during the import substitution era compared favorably with those enjoyed by workers in the more industrial countries. However, their wage power and the proportion of workers enjoying the rights remained far less. Labor in no Latin American country won universal economic rights3. Benefits are work-linked, and only selective sources of employment have gained labor rights. Around the time import substitution fell from favor about half of the urban labor force region-wide relied on informal sector work, unprotected by labor laws ensuring rights

Formal Sector Worker Protests

Formal sector workers first experienced improvements, but then a deterioration in their material wellbeing with the transitions to neoliberal democracies. Labor had previously experienced a retraction of rights, under the dictatorships that swept the region in the 1960s and early 1970s. Military governments repressed labor to create a more favorable investment climate. With the restoration of democratic rule, which the labor movements in many countries helped bring about (Foweraker and Landman 1997), work-based strife immediately surged. Wages rose as strike activity picked up (Noronha, Gebrin and Elias 1998).

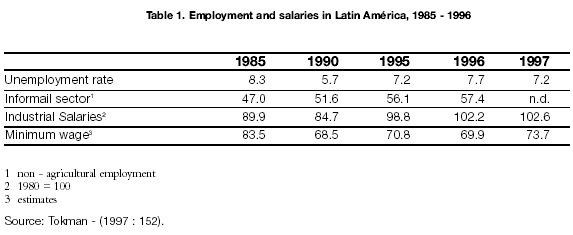

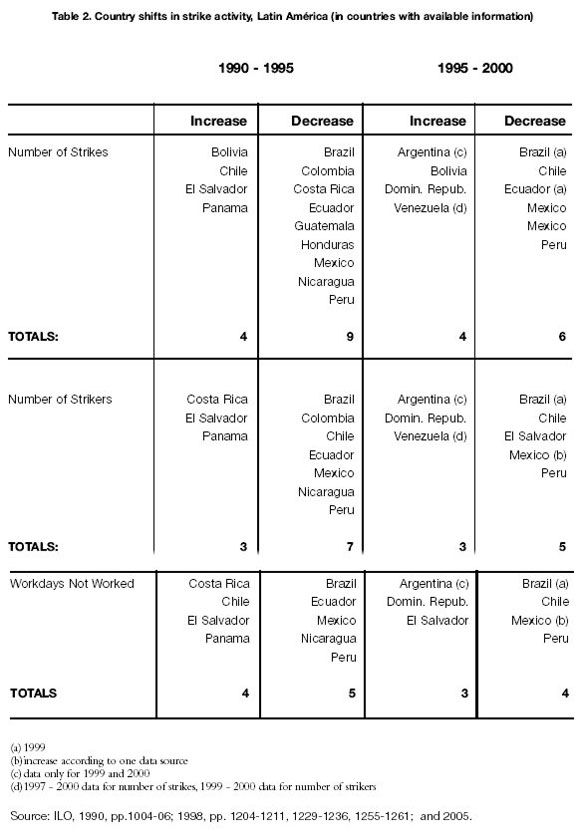

But by the 1990s formal sector workers found themselves unable to hold on to their recent gains. The new democracies did not formally retract labor rights, as had the military regimes, but they did not protect workers from the labor-unfriendly "invisible market." The removal of trade barriers subjected workers to global market competition which, in effect, weakened their labor power. Against this backdrop, labor strife tapered off, and jobs protected by labor laws contracted. According to country data reported to the International Labor Organization (ILO), the number of strikes, the number of workers involved, and the number of lost workdays declined in more countries in the region than it increased (see Table 2)4. Strike activity tapered off even though employment insecurity rose, income inequality increased, average industrial salaries barely recovered and the minimum wage remained below levels of 1980 (www.eclac.org/publicaciones/DesarrolloSocial/0/LCL.222OPE/Anexo_Estadistico_version_preliminar.els).

The tempering of labor strife in Latin America, against the backdrop of economic losses on the one hand, and the restoration of political rights on the other hand, is traceable to the manner that global market forces perniciously eroded labor's ability to exercise formal rights. Democratically elected governments became accomplices in the de facto retraction of rights workers officially regained, aiding and abetting the advancement of business over labor interests. Strike activity in Latin America contracted especially in the private sector, where under import substitution it had been concentrated. Global market competition under neoliberalism eroded labor's ability to deploy its historically most important weapon for defending and advancing its interests vis-à-vis capital.

Country experiences suggest that as of the 1990s strike activity centered mainly in the public sector (on Brazil, see Noronha, Gebrin, and Elias 1998, on Argentina, see McGuire 1995), and it occurred in the context of neoliberal state streamlining. The neoliberal attack on the public sector included union busting, to make state-owned enterprises more attractive to potential private investors (and buyers). This was true, for example, in El Salvador and Nicaragua. Governments also slashed public sector jobs, wages, and social benefits to rein in fiscal expenditures.They prioritized not only business interests but their own institutional fiscal interests over workers'.

Somewhat shielded from global market competition, public sector workers protested threats to their means of livelihood. Also working to public employees' advantage, states by their very nature are politically vulnerable, especially under democracies when dependent on electoral backing. For such reasons, along with savvy organizing, teachers, for example, have engaged in strikes to improve their earning power (see Foweraker 1993, Cook 1996). But public sector protests have not been sufficiently forceful to shield Latin American workers from some of the most far-reaching privatization programs in the world. Their inability to defend themselves from the brutal retrenchment of work opportunities reveals that the restoration of work-based rights with democratization was more formal than real and substantive.

Brief Comparison of Country Repertoires of Formal Sector Worker Strife

Workers' experiences varied within individual countries over the years, and among different countries at the same historical juncture, including independent of economic conditions. These variations, some of which I briefly highlight here, reveal the role of agency, on the part of labor and political parties that claim to speak in its name, and of democratically elected governments that in principle protect the social and economic rights of their people. They also reveal that labor asserted itself most in countries experiencing economic crises, when political controls over labor broke down and when, and if, labor shifted from focusing on the work place to their neighborhoods and society at large. And within and across countries labor in sectors vital to economies tend to be most effective in pressing claims. Labor strife is not explicable in terms of material conditions alone.

Argentina illustrates that there is no mechanistic relationship between economic deprivation and labor strife (McGuire 1996). There were fewer strikes, strikers, and days lost to strikes under President Carlos Menem in the 1990s, especially during the first half of the decade, than under President Raul Alfonsin in the 1980s, even though Menem eroded worker rights far more. As in other countries in the region, in Argentina democratization initially breathed new life into previously repressed labor.This explains why strike activity picked up under Alfonsin, the first democratically elected president in over a decade. But despite being democratically elected and despite having historic ties to the labor movement through the Peronista party, Menem kept a firm grip on workers, which made protest difficult. Menem used and abused political capital he attained from slashing inflation to turn on his labor political base.

Nonetheless, when the economy crashed around the turn of the century, as the full effects of Menem's extreme neoliberal restructuring (which included dollarization of the economy) were felt, conditions were so egregious that workers ceased to be submissive (James 2003). Strike activity increased, largely for restorative claims. Workers mobilized defensively to press for pension payments and unemployment compensation that they were denied but legally entitled to.They also protested for rights to payment for work rendered. Some public sector employees who had managed to retain their jobs had gone months without receiving cashable paychecks. This occurred in certain provinces where governments prioritized their own institutional economic concerns with fiscal deficit reduction and their own political priorities over workers' rights to payment for their labor. Decentralization of governance, one of the leitmotifs of neoliberalism, furthermore, left some provincial governments, as well as central government agencies, without sufficient revenue to cover their labor bills. Such was the rage that workers moved beyond their work place grievances and they broadened their strategies of resistance.They took to the streets to demand economy-wide change, namely an end to state neoliberal austerity policies. Angry workers set automobiles aflame, sacked buildings, and blocked vital foreign trade routes, while angry civil servants threatened to shut down schools, hospitals,and state-run offices.As the economic crisis caused businesses to be shuttered, some workers, desperate to retain a source of livelihood, even took over firms. Worker takeovers have been rare in the region5, and the Argentine takeovers involved women, a new base of labor resistance.

In Brazil, where economic problems never reached the scale of Argentina's, labor strife following the transition from dictatorship to democracy initially also was politically more than economically explained. As in Argentina, in Brazil the number of strikes and strikers, and duration of strikes, rose substantially initially with the political opening but then tapered off (Noronha, Gebria and Elias 1998). The number of annual strikes dropped from a peak of over 2,000 to under 1,000 in the course of the 1990s.While as in Argentina a reining in of inflation helped defuse tensions, the remains of strike activity in Brazil centered mainly in the slimmed down public sector. And also as in Argentina, workers were especially indignant when local governments, in the context of neoliberalinduced administrative decentralization, withheld paychecks.

Yet in Brazil, labor that lost power at the work place through protest gained formal political power nationally.Well organized and under the savvy leadership of Luis Ignacio Lula da Silva, popularly known as Lula, the Workers Party won the presidency in 2002.With his government subjected to the same neoliberal strait jacket by international financial institutions as non labor-led governments, workers quickly found themselves, in many respects, benefiting symbolically more than materially. Lula's government did not turn on labor as Menem's had, but even with labor winning command of the state more powerful global forces kept its influence at bay.Some programs of Lula's government targeted the poor and in ways that somewhat reduced income inequality in a country with one of the worst distributions of wealth in the world, but the formal political power that organized workers gained, brought them little economic gain.The labor movement found itself exchanging, in effect, improved economic rights for the political right to rule.

The Chilean experience further illustrates how neoliberal restructuring with state backing muted labor demands, including when labor secured representation in governance. Chile, the first country in the region both to downsize massively its state sector and to eliminate barriers to trade, did so under a military government that brutally repressed labor. As unpopular among workers as were General Pinochet's labor policies that caused living standards to plunge and many workers to lose their jobs, the risks of asserting collective claims were so great that strikes were rare and only minimally coordinated.Against the backdrop of the risks, workers in such economically vital foreign exchange earning sectors as mining helped play a key role in the movement to restore democracy (Garreton 1989/2001 and 1995).

Civilian rule, which defiant workers helped bring about in the streets if not the work centers, gave rise to a reinvented labor movement, and a reinvented socialist party in turn, that in its new incarnation won the presidency in 2000 and again in 2006.Years of repression and memories of repression led workers, among others, to bury their militant pasts.They came to settle for distributive over redistributive gains, against a backdrop of growing inequality in the allocation of wealth as business benefited more from the economic growth Latin America's most successful neoliberal economy ushered in. A Center-Left political pact contained labor demands, though not by use of force.

A different mix of political-economic conditions similarly tamed labor in Mexico, with less pay-off to workers.There, state-crafted business-labor pacts caused both real wages to fall and income inequality to rise (Ros and Lustig 2003). In agreeing to the pacts, the main labor confederation lent formal support to worker-unfriendly stabilization policies. While labor never gained the upper hand in the pacts, the hegemonic hold of the Party of the Institutionalized Revolution (PRI), with which labor for decades had been formally affiliated, whittled away. The Left-leaning Revolutionary Democratic Party (PRD) won elections with break-off labor support, at the municipal and congressional levels, although mainly only in the south and central regions of the country, not in the increasingly richer industrial north. Unlike in Brazil and Chile, though, labor remained out of favor at the national political level. Indeed, when the PRI lost the presidency for the first time in 2000, it lost out to the conservative pro-business party, the National Action Party (PAN).And six years later PAN won the presidency once again, although this time with a laser-thin victory over the PRD. Meanwhile, in the absence of a pact among politically organized social groups, democratization resulted in congressional stalemates with little economic pay-off to labor of a distributive as well as redistributive sort.

While the pacts in Mexico tamed labor mobilizations in the private sector where capital was the main beneficiary, and did so in the absence of brutal repression as in Chile, two deep recessions, in the 1980s and a decade later, stirred some new bases of unrest in the public sector. Even though strike activity overall declined in the context of exceptionally high increases in living costs (Tables 2 and 3), a gradual erosion of government legitimacy led a broadened range of aggrieved public employees to be less submissive than in years past. Well publicized political scandals and poor economic management, and new political party contestation so fueled, contributed to the erosion of PRI-dominated state legitimacy.Against this backdrop, some public employees turned to new strategies to assert collective claims. Public sector nurses, upset with shortages of medical supplies in the hospitals where they worked, for example,publicly drew blood from their arms with syringes that they then squirted at the doors of hospital administrators (New York Times 21 January 1997: 10). They turned to such strategies, capturing the popular imagination, as government control of the media diminished with democratization.

Against the same macro political and economic backdrop, low-skilled public sector workers in Mexican provinces also protested abuses. Illustrative, in 1997 streetsweepers in the state capital of Tabasco collectively pressed both for compensation for private services politicians exacted of them and for job reinstatements when austerity policies cost them their employment. They staged a hunger strike, marched en masse to Mexico City, and stampeded into congress where they peeled off their clothes to press their claims (New York Times 21 January 1997: 10). Like the nurses, the streetsweepers turned to new creative post-modernesque ways to express their rage, to attract attention to their collective claims in the context of new democratization-linked media access.

At the century's turn Venezuela, under Hugo Chavez, was the one country where a democratically elected government tried to centralize power and use it purportedly to the benefit the poor (the Bolivian case, more recent, is addressed below). In doing so, though, Chavez stirred the rile not only of the middle and upper classes accustomed to privilege, but also of the most privileged organized workers. Businessmen, along with the oil worker "labor aristocracy" in a vital economic sector, stopped production, closed down stores, and took to the streets in protest. They resorted to the typical weapons of the weak, presuming that in destabilizing the economy they would bring the Chavez regime to heel. They also backed a coup d'etat.

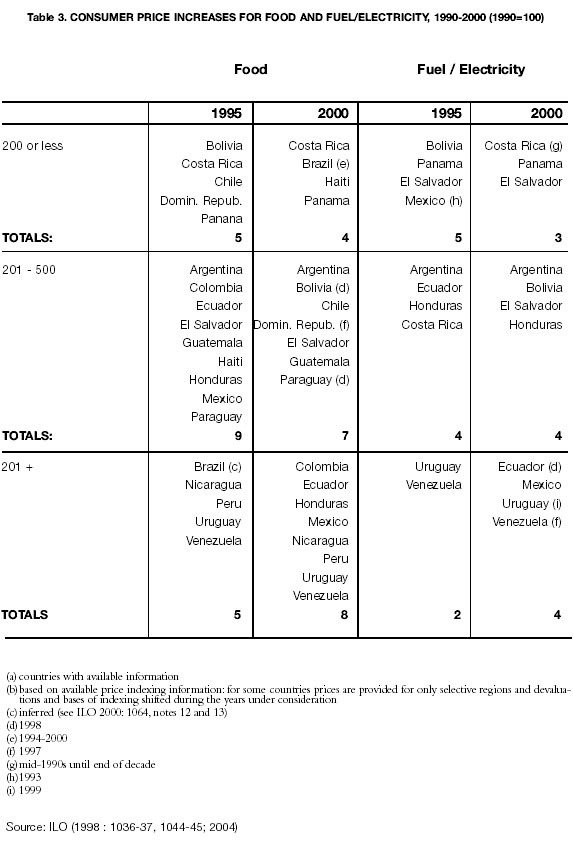

While Chavez weathered the storm to depose him, which in 2004 also included an opposition-organized national referendum, the strife debilitated the government and left ordinary people with few improvements in their level of well-being. Despite Chavez's populist rhetoric, available evidence suggests that even in Venezuela under his rule whatever improvements in well-being ordinary people experienced neither entailed an improvement in income distribution nor a reduction in the poverty rate (according to the most recent United Nations data available, at the time of writing, for 2002). Under Chavez's watch income redistribution deteriorated slightly and the poverty rate at first declined but beginning in 2000 increased)6. Chavez handled his populist agenda in an inflationary manner, driving living costs up for the very populace he purported to defend (see Table 3), and by contracting Cuba for teachers and especially medics to provide social welfare services free of charge to Venezuela's humble stratum in exchange for oil.

Transnational Alliances and Consumer-Based Labor Movements

Unionization and strikes to improve work conditions proved particularly difficult in the new low-skilled labor intensive export-oriented industries that mushroomed, especially in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America. The expansion of so-called maquila production was tied not merely to the global neoliberal restructuring that removed cross-border trade and investment barriers but also to such politically negotiated accords as NAFTA, the Caribbean Basin Initiative, and, most recently, the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), that granted signatory countries privileged access to the U.S. market (under circumscribed conditions). Business took advantage of the new economic opportunities the neoliberal-linked reforms and transnational agreements made possible, plus the low cost of labor in Latin America7. Maquila production expanded as the U.S. and other rich countries with high labor costs deindustrialized.

Management repression and ability to locate, and relocate, globally wherever it perceived its investment options best, kept workers from pressing for improved work conditions. Under the circumstances a new cross-border labor-friendly strategy evolved (Anner 2003; Ambruster-Sandoval 2004; Porta and Tarrow 2004). It centered on solidarity mobilizations in the rich countries: on initiatives by human (including child labor) and women's rights groups and transnational consumer-based social movements. Movements for worker rights became delinked from the point of production. The success of these movements has rested on conditions created, not preexisting, and on movement participants willingness to sacrifice their own material interests.When labor sympathizers organized consumer boycotts in wealthy countries to press firms to improve conditions for workers, they ran the risk that increased labor costs would be passed on to them in higher prices for their purchases.

Although multinational firms had the upper hand, they were not without their own vulnerabilities, including through exposure of their sweatshop conditions, as in the Kathie Lee Gifford /Honduras uproar.Threats of boycotts in the U.S. from the multi-campus United Students Against Sweatshops movement, and embarrassment from bad media exposure, exerted some pressure on companies to temper their exploitation of Latin American labor. In calling for consumer boycotts of goods produced by internationally renowned companies (and their suppliers) shown to deploy deplorable labor practices, the anti-sweatshop movement has exerted some pressure to improve factory work conditions. How successful this strategy will prove remains to be seen.

The Informal Sector Independently Employed: Struggles for the Right to Work

Conditions for most workers typically are worse in the informal than in the formal sector, both because governments in the region rarely have granted informal sector workers labor protections and because these workers are subject to widespread competition that keeps their earning power low. Unlike in the wealthier countries where the informal sector shrank as industrialization advanced, in Latin America the informal sector has remained large, and it expanded in size in the 1990s (see Table 1), including in some of the most successful economies in the region, such as Mexico, Brazil, and Peru (Centeno and Portes 2006, essays in Portes, Castells, and Benton 1989). Close to 60 percent of the labor force regionwide is estimated to work in such highly precarious jobs.

Because informal sector work life is individuated as well as competitive, rarely do laborers so employed press collectively for shared grievances. Street vendors are among the few informal sector workers to have mobilized across the region, largely in self-defense. They have staged collective actions to make claims on the state, especially in Mexico and Peru. In Mexico City would-be vendors borrowed tactics from squatter settlement land invaders (addressed below) for rights to space to sell.They have collectively "invaded" sidewalks, streets, and other public places, and pressured authorities to honor their locational vending claims (see Eckstein 1988 and 2001: 329-50). Cognizant that vending is labor-absorbing and that widespread unemployment is politically explosive, officials often acquiesce to vendor pressures. Authorities have been most accommodating when vendors have had the support of influential politicians and when their leaders have deftly manipulated the political system (Cross 1998).

In August 2004 an unprecedented broad alliance of informal sector workers took to the streets in rage in Mexico City, when the government appeared on the verge of clamping down on poor people's claims for a basis of livelihood. Protesters included self-employed parking attendants, windshield cleaners, open-air musicians, and disabled gum sellers, along with subway vendors (www.wola.org/mexico/police/dmn_081104.htm). What sparked their collective defiance? Opposition to a new "civic culture" law that made their jobs illegal. New York City former mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, had recommended the restrictive statute. A business coalition, dismayed about the breakdown in law and order in the city, had hired Giuliani as a consultant. A law that might work in New York City, however, exacerbated social and economic tensions in Mexico's capital, where citydwellers turned to such jobs less by choice than default, unable to find other work and without recourse to welfare for those unemployed.

Street vendors also mobilized in Argentina, which historically ranked among the countries with the smallest informal sectors in the region. Formerly secure workers who took up street vending when losing formal sector jobs with the economic downturn protested police efforts to evict them in the downtown commercial promenade. They were joined in their protest by a social movement of the unemployed. Police stepped in when local businesses threatened the government not to pay taxes unless authorities removed their street competition. Pressed to choose, the government sided with established businesses, as governments in the region have historically typically done

The movement of the unemployed with which vendors allied itself is noteworthy. Such a movement is exceptional in the Latin American repertoire of resistance. It took the economic crisis to induce its formation. The MST, the acronym for the movement of the unemployed, staged protests for jobs and health and education services . MST protests and demonstrations, in turn, built on the support of hundreds of organizations and civic movements in neighborhoods ranging from old industrial slums to middle class enclaves that gained vibrancy in the context of the crisis. But the movement of unemployed quickly became politically and ideologically divided, as diverse groups on the Left tried to capitalize on the discontent.

Divisions aside, at the community level neighbors joined together in asambleas barriales and asambleas populares, to address shared concerns (see Gonzalez Bombal, Svampa, and Bergel 2003; Di Marco, Palomino,and Mendez 2003)8. Citydwellers, accordingly, protested their plight collectively in multiple and overlapping settings: not only where they had claims to work but also where they lived. Many leaders of the new movements had previously been active in labor unions. Old bases of labor organization thereby influenced new bases of collective struggles and for a broader range of concerns.

Struggles over the Cost of City Living

Worker struggles to improve income might be expected to fade from fashion for economically explicable reasons if living costs lessened as earnings declined.However,living costs rose immediately with the onset of neoliberal restructuring. While government subsidies had kept urban living costs low under import substitution, when governments in the region were pressed by international creditors to reduce fiscal expenditures in conjunction with the restructuring, they retracted both food and utilities subsidies. The retraction of the latter rested on privatizations of previously publicly owned service provisioners.

Protests for Affordable Food

Ordinary citydwellers across the region had come to consider food subsidies as a basic right, a subsistence right. It was also a material benefit they counted on to make city living affordable and migration from the countryside therefore feasible. Against this backdrop, people experienced government-permitted hikes in prices of basic foods as a tacit state violation of a moral contract (Eckstein and Wickham-Crowley 2003b: 8-16). Making cutbacks in food subsidies all the more egregious, many governments simultaneously devalued their currencies which caused living costs to spiral.

Against this backdrop, food price hikes fueled unrest. While consumers typically directed their anger at authorities perceived responsible for the rise in food prices they considered unjust, angry citydwellers on occasion also looted supermarkets (e.g. in Argentina and Brazil) where they experienced sudden jolts in the price of food fundamentals. Urban consumer revolts occurred in at least half of the Latin American countries just in the 1980s (c.f. Walton 1989/2001and 1994), and in Ecuador, Bolivia, and Argentina through the early years of the new millennium.These revolts are the modern day equivalent to the sans culottes' and workers' bread riots of eighteenth and nineteenth century France and England, and the urban equivalent to peasant rebellions stirred by the erosion of subsistence rights claims (Scott 1976).

Systematic information on incidences of urban protests over subsistence claims, both across countries and within individual countries over time, unfortunately is non-existent. To assess the relative importance of consumer, in comparison to other bases of defiance, I coded incidences of protest recorded in 1995, ten years after most governments in the region initiated their first cutbacks in urban food subsidies in conjunction with neoliberal restructuring. I recorded incidences reported in the Latin American Weekly Report (LAWR),a news summary source on Latin America of high repute. Because LAWR describes only the most important incidences and underreports ongoing unrest, it provides only a rough approximation of actual tumult. Qualifications aside, LAWR reported consumer protests in six countries (over education costs as well as retail prices). During the same year it reported protests against neoliberal-linked state-sector downsizing and privatizations in ten countries, and against wage reforms (including proposals to eliminate the indexing of wages to cost-of-living increases), the elimination of the right to strike and organize, cutbacks in labor security (through new, more flexible hiring policies), and paycheck-withholding for work rendered in eleven countries.

Assessing the situation cross-regionally since the onset of neoliberal restructuring, John Walton (1998 and 1989/2001) concluded that no other region in the world experienced as many protests centering on food, along with protests centering on increases in prices of such so-called collective goods as electricity and water, as Latin America (Walton).With Latin America the most urbanized Third World region, proportionally more people there both depend on the market for food and services and benefit from consumer subsidies under import substitution. Protests in Latin America also were more gendered than elsewhere in the world, that is, more female-based, and more secular in orientation. Women's greater involvement in Latin America resulted from their greater absorption into the paid labor force and life outside the confines of the home, along with their greater dependence on the market for subsistence. And in countries such as Peru, Guatemala, and Chile, women‘s participation in consumer protests built on collective involvements in such neighborhood and parish based groups as soup kitchens and food-purchasing cooperatives. Non-governmental organizations, NGOs, had helped organize such groups when government-initiated austerity policies had made subsistence exceedingly problematic for urban poor in the early to mid-1980s.

Table 3 gives a sense of why cost of living increases stirred collective rage. Between 1990 and 1995, as well as between 1990 and the century's turn, food prices in most countries at least doubled. By the end of the 1990s eight countries experienced more than a five-fold increase in food costs. The food index, of 100 in 1990, rose to over 1,000 in Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Nonetheless, as in the case of strike activity, cost of living protests is not entirely economically explained: neither their incidence nor their form. Protests ranged in form, from demonstrations, strikes, riots, and looting; to attacks on governmental buildings. The form varied by country. They varied with national repertoires of resistance, cultural traditions, and organizational and associational involvements, as well as with macro political-economic conditions, state-society relations, and group alliances. Cutbacks in subsidies, for example, stirred riots in Jamaica,Argentina,and Venezuela, street demonstrations in Chile, and strikes and roadblocks in Andean nations. Protests also varied in how violent they turned, largely depending on how public authorities responded. Protests in cities across Venezuela against cutbacks in consumer subsidies turned especially violent in 1989. Hundreds of protesters there were killed in consumer protests known as the caracazo (Coronil and Skurski 1991: 291). It was against this backdrop that Chavez was initially elected in the late 1990s. State violence turned ordinary Venezuelans against the rule of elite-linked parties. Chavez represented a break with the oligopolistic parties of the past.

The assaults on former tacitly agreed-upon urban subsistence rights, nonetheless, typically only stirred public protest under certain political conditions. Democratization itself did not necessarily prepare the ground. Protests occurred especially where governments were weak and unpopular and where political divisiveness and power struggles prevailed. Under such circumstances the risks of rebellion were less and the possibility of gaining political support greater. Where political contestation was minimal and the state comparatively strong, widespread consumer subsidy cutbacks rarely led unhappy citydwellers to take to the streets.This was especially true in Mexico as long as the PRI retained national power, when the cost of living rose considerably, but even afterwards.

These seemingly spontaneous protests typically involved some degree of coordination (c.f. Walton 1998 and 1989/2001). They occurred especially where backed by labor unions. Social class in its organized form accordingly shaped mobilizations to lower living costs, at a time when strikes for higher wages that would make consumer price hikes more affordable became difficult. Protests also occurred where backed by clergy inspired by Liberation Theology, which called for concern with the poor. In Brazil the Catholic Church played an especially active and visible role, including at the national level.There, in 1999 the national bishops' organization sponsored demonstrations against state withdrawal of subsistence protections, as well as against other neoliberal policies.They called their movement "The Cry of the Excluded Ones," and coordinated their activity with unions, and with parties of the Left and the increasingly influential Landless Workers Movement (MST).

Thus, consumer protests became a new addition to the Latin American social movement repertoire at the same time that work-based protests subsided. The new economic order alone, however, does not account for the shift in bases of collective action. Even the scale of price hikes has not in itself determined when angry citydwellers rebel. Consumer protests against rising living costs typically occurred when encouraged and led by labor, parish, neighborhood, and other groups.

The impact of cost of living protests, in turn, varied across the region. When defiance was broad-based, insurgents often succeeded in getting governments to retract or reduce price hikes (Walton 1989/2001). Yet, Table 3 reveals that whatever impact protesters had on containing price increases proved short-term and limited, in that food costs dramatically rose in most countries in the region in the course of the 1990s, including in countries where mobilizations against surges in the cost of living transpired.

When governments temporarily cut back price hikes they did so for their own institutional reasons: to restore order and legitimate their continued claims to rule. Occasionally governments, such as Brazil's under Fernando Henrique Cardoso, responded to stepped up nationwide protests with ambitious spending programs. But some weak governments even upon restoring consumer subsidies collapsed under the weight of unrest. This occurred in Ecuador both in 1997 and 20009. Although Ecuador had experienced far from the highest food, along with fuel, price increases in the region between 1990 and 1995, food prices nearly doubled between 1995 and 1997, and by 2000 the food price index, on a base of 100 in 1990, had spiraled to over 3,000 (see Table 3, and sources)10. Rage over the rise in subsistence costs drove trade unionists and teachers, together with indigenous groups mobilized around new claims to ethnic rights, into the streets.

As angry citydwellers in Ecuador staged road blocs that paralyzed the country, officials found themselves between a rock and a hard place. In attempting to appease protesters and restore order, by rolling back contested price increases, Ecuadorian governments defaulted on foreign loans and initiated overarching hyperinflationary policies that made them yet more unpopular.

Similarly, in Argentina food riots contributed to the downfall first of President Fernando de la Rua's government and then to the governments that briefly followed in the first years of the new millennium. While Argentina had not ranked among the countries with the highest hikes in food costs, widespread unemployment and impoverishment, and then an official devaluation of the local currency, priced basic subsistence beyond most citydwellers' reach.Yet, the struggles for subsistence rights rested not merely on new and unprecedented economic insecurity. The neighborhood, work-based,and other organizations that the general economic crisis fueled, coordinated the food riots, along with other protests, and induced the desperate to seek collective redress.

Aware of the politicizing effects austerity measures often have, some governments targeted anti-poverty funds selectively to preempt collective resistance to cost of living increases. President Salinas (1988-1994), through his famed Solidarity Program, for example, in Mexico masterfully channeled social expenditures to communities his administration considered politically problematic, in a manner that made beneficiaries directly indebted to, and dependent on, the central government.The Fujimori government in Peru similarly targeted anti-poverty funds, and in so doing weakened the influence of grass-roots community organizations that had mushroomed in opposition to subsidy cutbacks. Fujimori's autocratic interventions, which concomitantly reined in the guerrilla group, Shining Path, managed to contain consumer revolts as food prices soared. The food price index jolted from a base of one hundred in 1990, when Fujimori first came to power, to over a thousand mid-decade. Prices during the five year interval raised more in Peru than in all countries in the region besides Nicaragua.

While Fujimori managed to stave off subsistence rights protests, he proved unable to hold on to power. Exposure of abuses of democracy, particularly of corruption at the highest levels of his administration and of vote-rigging, were the immediate causes of the movement that drove him from office, all the while that anger brewed over deteriorating living standards. Fujimori's successor, Alejandro Toledo, dark-skinned and born poor, came from a background with which most Peruvians could identify, since they still were impoverished and of indigenous heritage.Although Toledo won a landslide victory in 2001, in failing to keep his electoral promise to create jobs and alleviate poverty to offset the steep rise in living costs, workers, teachers, and others in cities and towns across the country took to the streets to demand better pay and better work conditions and to oppose privatizations that drove living costs up under his political watch. Food prices rose even higher than under Fujimori, although not as high as in Ecuador, Venezuela, and Nicaragua (see Table 3 sources). Living costs, together with a litany of other grievances, resulted in Toledo's popularity plunging to the single digits, to the lowest level of any president in the region. Urban unrest across the country became a near daily occurrence11. However, Toledo managed to keep food protests minimal by continuing targeted food subsidy programs (from which reputedly 20 percent of the population benefited)12. The government's Vaso de Leche (Glass of Milk) program partially offset the general rise in food costs, and the very administration of the program, including through neighborhood committees, no doubt helped deflect consumer rage.

In sum, citydwellers experienced neoliberal linked state cutbacks in food subsidies as unjust. It was government violation of their moral and not merely material economy that fueled food riots. But neither state reneging on its tacit social contract nor the scale of price increases in themselves determined when indignant urban residents took to the streets. Protests were very much contingent on the institutional and cultural context in which citydwellers' lives were embedded. Where civil society organizations brought angry consumers together and leaders instilled a sense that the dramatic increases in living costs should not be tolerated, and where governments were weak and the polity politicized, consumer protests were most likely. Democratization made protests easier while not ensuring citydwellers the right to affordably priced food.

Struggles for Affordable Housing and Urban Services

Under import substitution many citydwellers came to feel entitled to affordable housing and affordable urban services, such as transportation, piped water, and electricity. Populist regimes before the military takeovers had accommodated to these claims, to consolidate political support while ensuring a cheap labor force for business. If city living costs were low, so too could wages be. The provisioning of affordable housing and services accordingly benefited the popular sectors, business, and the state simultaneously.

The most distinctive feature of the Latin American urban landscape in the import substitution era had been the mushrooming of squatter settlements on the periphery of cities. In the new settlements city-dwellers collectively took to the offense: they staked out land where they had no prior claims. Governments typically tolerated the land takeovers provided they occurred on public (or on politically weak peasant) lands, for several reasons. They addressed city people's needs for shelter at minimum cost to the state. They were politically popular.And land recipients could easily be manipulated politically, votes exchanged for rights to property and the provisioning of urban services13. Sometimes governments even successfully pressed settlers to absorb costs of urban services.

Under neoliberalism, however, collective mobilizations for urban land rights tapered off (Durand-Lasserve 1998; Márquez 2004; Tironi 2003). For one, the squatter option became less attractive to ordinary city folk with limited economic means once the cost of living in such settlements increased with the privatization of service provisioning. For-profit companies, detailed below, raised rates for services. Two, the public lands where governments had tolerated "squatting" by the century's turn had mainly been claimed.Three, the neoliberal governments were biased toward market, not political, housing solutions. Consistent with their bias, they favored commercial dealings over land invasions, a more business but less poor-people friendly way to build up the city housing stock. As a result, the deepening of neoliberalism eliminated citydwellers' most effective means to minimize their housing costs, through collective land invasions.

Reflecting the rise in urban infrastructural costs with the neoliberal transition, some two-thirds of the countries with available information experienced more than a doubling of fuel and electricity prices in the 1990s (see Table 3). Cost of urban service protests that occurred against this economic backdrop often were tied to privatizations of previously state provided and subsidized so-called collective goods.

In Ecuador, for example, it was cutbacks in gasoline and not merely food subsidies that proved the undoing of the two democratically elected presidents deposed in Ecuador in the 1990s. Ecuador's exorbitant increases in fuel and electricity charges were the highest in the region. Gasoline price hikes were also implicated in Venezuela's 1989 caracazo, while in Argentina the government's announcement of utility price hikes amidst the country's economic crisis led people in cities across the country to take to the streets in rage. In 2002 Argentines staged a blackout, in protest against huge rises in telephone, heating gas, and electricity rates, on top of the unprecedented unemployment and impoverishment the economic crisis caused. (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/2280537.stm).

Privatization of utilities companies, and the price hikes in services that ensued, brought angry Peruvians into the streets as well. Governments in the country that through targeted anti-poverty programs contained consumer protests as the cost of living overall spiraled met with resistance to cost-of-services increases. Anti-privatization protesters at one point shut down the country's second largest city. But widespread unrest left the government weak and society divided, with ordinary Peruvians' plight unresolved.

The provisioning of utilities became especially contentious in Bolivia. In Cochabamba, the country's third largest city, poor people protested against an American company the government contracted to take over the provisioning of the city's water supply. The World Bank pressured Bolivia to privatize water delivery as part of a broader campaign to get Bolivia to privatize state enterprises. The neoliberal-biased but democratically elected government tacitly sided initially with the foreign firm which it guaranteed a 16 percent rate of return on its investment and permitted to raise water charges dramatically14.The protests built on social movements brewing nationwide, including among indigenous peoples stirred by newly awakened claims to collective ethnic rights, and among coca growers angry about government eradication of their crop when pressed by Washington in conjunction with its war on drugs.

Hugo Banzer, president at the time, called on more than one thousand police in February 2000 to crush demonstrators. Hundreds were injured, one person died. Under duress though the government cancelled the foreign contract, when pressed to choose between helping a foreign firm profit while lowering its fiscal expenditures, and averting collapse of its legitimacy. Confronted with massive mobilizations by people considering the price hikes, along with other policies, unjust, the government retracted the foreign contract (leading the foreign firm, in turn, to sue the state).

The Bolivian, like the Ecuadorian government, found itself between a rock and a hard place. Its legitimacy was so frail, in light of the social movement momentum, that it imposed a state of siege. It, in essence, curbed citizen civil rights after having retracted its tacit social contract to provide affordable living.

While the state of siege restored order in the short-run, the humble neither forgot the "water war" nor forgave its perpetrators15. Nationwide, diverse groups of aggrieved increasingly coordinated their protests, targeting their anger against those they dubbed "the neoliberals." In December 2005 they together succeeded to elect Evo Morales, the dark-skinned former leader of the cocaleros, the coca growers, president, with the largest vote of any contender for the office in the country's history.Anger over state complicity in the price hikes in living costs contributed to, although alone did not cause, the historical shift in who in the country was elected to rule.

The 2005 election marked the first time in Bolivia's history that poor people elected a person who shared their humble origins to the highest political office in the land, following the footsteps of their social counterparts in Peru in 2001 and in Brazil the following year. Humble folk throughout the region have strength in numbers, which when given the opportunity they increasingly are using to support politicians born in their ranks. In Bolivia more than in the other countries the new political turn, however, rested on mobilizations on the part of newly politicized groups in civil society, which alongside labor, with a long history of militancy, asserted claims.The politicized pursued a dual strategy, in the streets and at the ballot box.

Crime and Struggles for Safe Cities

Latin Americans across the region became so disaffected with the new economy and new felt injustices that increasing numbers of them also responded in ways that eroded the moral order of cities, through more individuated (though sometimes coordinated), violent, and anti-social venues (Caldeira 2000; Portes and Roberts 2005). Collective pro-active actions proved far from the only response to neoliberal restructuring. Indeed, a surge of disaffected citydwellers from Mexico to the Southern Cone turned to theft, pilfering, looting, gang activity, kidnappings, and killings16. Colombia became the kidnapping capital of the world, with Mexico not far behind17. In 2001 a kidnapping occurred in Colombia every three hours. Crime generated more crime as a culture of illegality set in, and as criminality went unpunished. Poverty and unemployment, along with drugs, police corruption, and the entrenchment of leaner and meaner governments, were at the root of the rise in the illegal activity. In many countries law enforcement agents even became part of the problem, not its solution, as they joined the ranks of the criminals and operated with impunity.

The surge in criminality gave rise, in turn, to massive new multi-class anti-crime movements, in capitals across the region. Participants demanded tougher government anticrime measures. Seeking unity and publicity for their cause, protesters made use of culturally crafted symbols of resistance which they, like other defiant groups, could deploy to capture the popular imagination through democracy-improved media access. These new movements to the Latin American protest repertoire brought the middle classes across the region into the streets. In Rio de Janeiro in 1995 a civic group, Viva Rio, for example, oversaw a massive demonstration for a cleanup of the police department, as well as improved urban services. Hundreds of thousands of rich and poor and old and young, cloaked in white, joined the demonstration, React Rio. In Rio, favela dwellers independently organized to press for improved neighborhood security, including against police incursions and drug-traffickers. And in Colombia four years later an anti-kidnapping protest drew hundreds of thousands of citydwellers, also clad in white, to demand tougher government action against criminals. The same year in Mexico City tens of thousands of frustrated and frightened residents of all social classes, but especially of the middle class, in turn, paraded with white ribbons and blue flags in outrage over the mounting wave of violent crime there. Anticrime city-wide protests occurred again in Mexico City in June and August of 2004. They were the city's largest mobilizations in recent history (www.manattjones.com/newsbrief/20040909.html

www.amren.com/mtnews/arhcives/2004/08/hundreds_of_tho.php). The marches were organized by crime victim groups, but scores of human rights, civic, and public interest groups joined in. Meanwhile, Argentines as well, in 2004, took to the streets to demand a government crack-down on crime.

In these various instances, as in the case of consumer protests, the deepening of neoliberalism alone did not prompt the collective resistance. However, in slimming down the state's role in the economy and society, and in generating new inequities, new injustices, and new insecurities, the economic restructuring fueled crime, and anger about crime in turn. Democratization was not the source of citydwellers' new plight but it proved not its solution either. Yet, it created a political opportunity structure that made the movements more likely, in reducing the risks of protest and allowing for greater media coverage.The media coverage sparked both interest in and knowledge about the protests, and in so doing broadened the base of collective defiance. At the same time, democracy-linked electoral competition induced opponents of government incumbents to encourage participation in the broad-based anticrime movements, to help discredit officials' ability to maintain law and order. In Mexico City, for example, the anti-crime protests in 2004 were partially supported by the middle classes wishing to discredit the then mayor, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, a populist, who they feared might win the 2006 presidential election (and, as noted above, came very close to winning to his most conservative opponent that the wealthy and middle classes supported). In similar vein, a businessman orchestrated and financed a-quarter-of-a-million- large protest to discredit Buenos Aires' left-leaning mayor,Anibal Ibarra,as well as to demand tougher laws against kidnappers. Outrage with the kidnapping and killing of his son stirred him to build on the bedrock of anger with the breakdown of law and order in the city.Yet, even if political opportunism in such instances sparked the anticrime movements, civil society support built on the insecurities that the breakdown of law and order under neoliberalism induced.

In Colombia, more than in any other country in the region, the preoccupation with public safety became so widespread as to help elect, at the dawn of the new millennium, a president on, first and foremost, a "law and order" platform: Alvaro Uribe. Civic order had so decayed that the populace put concerns with economic injustices aside.

Conclusion

Whatever the economic logic to Latin American neoliberal restructuring, the deepening of the reform process carried seeds of obstruction to its unfettered permeation, though not, at least to date, seeds of its own destruction. State sector downsizing, and trade and price liberalizations, addressed state fiscal exigencies, but so too did they generate unemployment, new economic vulnerabilities, and cost of living increases for city people who could ill-afford them. Meanwhile, a surge in crime made life in cities unsafe and unbearable for folk across the class divide.Accordingly,the removal of market encumbrances generated new grievances that brought new, distraught groups to the streets. Democratization restored political rights military governments in the region had retracted, but it has yet to institute formal channels through which new market generated grievances are adequately addressed.

The range of Latin American economically driven social movements under neoliberal democracy suggest the following propositions:

When citydwellers protest aspects of the new economic model they find especially egregious they initially do not defy the neoliberal restructuring in the abstract. Rather, they rebel against neoliberalism as they directly experience it in their everyday lives. However, as the range of groups and sources of grievances build up, the economic model itself, and its domestic perpetrators, become targets of rage. Anti-globalization protests abroad, although beyond the scope of this essay, contribute to the framing of some of the movements, but the root causes of the movements are grounded in conditions citydwellers in Latin America themselves experience.

There is no mechanistic relationship between neoliberal-based material deprivations and defiance. Political structures and processes, including state structures, state/society relations, leadership, alliances, and the vibrancy, politicization, and organization of civil society, are mediating factors influencing how victims of reforms respond. The weaker the state on the one hand, and the more politicized society and less institutionalized state/society relations on the other hand, the more probable that economic grievances stir collective resistance.

Neoliberal restructuring has shifted the Latin American repertoire of resistance from the point of production to consumption, and within the arena of consumption from pro-active claims for affordable housing to protests against increases in the cost of living.This shift has transpired in the context of neoliberal restructuring worldwide, in which labor at the work place has increasingly been subjected to pernicious invisible market forces and to visible policies of international financial institutions that weaken its ability to exercise formal rights to organize and strike in self-defense restored with democratization. Global competition has made strikes a too risky and ineffective weapon for most workers to turn to when they consider their low earnings and poor and declining purchasing power unjust. Under the circumstances, some cross-regional solidarity movements have taken a form that threatens firms with consumer boycotts if the manufacturers do not improve work conditions where they produce. More frequently under the circumstances, labor, together with poor and lower middle class people, have shifted to collective disruptive efforts to halt cost of living increases, first in the price of basic foods but more recently in costs of urban services.Their protests have tempered price jolts, but more in the short than long run. At the same time, collective resistance to specific neoliberal reforms is having a spillover effect in the formal political arena, where angry and newly politicized groups increasingly are using their new and restored political rights to elect into office people who share their humble origins and who claim to speak in their name. Urban constituencies increasingly in Latin America thus are combining institutional and non-institutional means to press claims.

As economic conditions deteriorate and state social controls break down, resistance increasingly is also taking more anti-social forms. Crime has become so endemic as to make cities unsafe. Against this backdrop, cross-class movements have emerged demanding that cities be remade more livable.

Comentarios

2 I base this article on years of following social movement developments in Latin America. Because my goal, here, is interpretive, I only provide selective references and mainly only to document factual statements for, at the time of writing, recent social movement developments.The interested reader may wish to consult essays in Eckstein (ed.) (2001) and Eckstein and Wick-ham-Crowley (eds.) (2003a and 2003b), and references therein, that inform my analysis.The interested reader might also wish to consult the anthologies focusing on Latin American social movements edited by Jelin (1995), Escobar and Alvarez (1992), Calderon (1995), and Alvarez, Dagnino and Escobar (1998), although they include few articles that specifically address social movements with economic roots.

3 Cuba under Castro is an exception.The entire population there qualifies for the right to universal health care, and all state workers, the majority of the labor force, qualify for pensions, unemployment, and other benefits. However, workers there lack the right to organize freely, independent of the state, and to strike, to defend collectively shared interests.

4 The ILO data unfortunately only provide an approximation of actual strike activity.The organization's compilations are based on different types of sources in different countries,e.g. employers and workers organizations, and official labor relations records, and not on uniform indicators of strike activity across countries.

5 Workers deliberated whether the factories they seized should be transformed into state-owned firms or remain worker-owned cooperatives. Personal communication from Carlos Forment, November 2004.

6 www.eclac.org/publicaciones/DesarrolloSocial/0/LCL.222OPE/Anexo Estadistico version preliminar.xls, Table 25 and 0/LCL2220PI/PSI-2004_cap1.pdf,p.13.

7 However, because labor in China is even cheaper as well as docile, subcontracted production increasingly is moving here

8 By 2005 nearly all neighborhood groups had become moribund.The economic crisis also fueled more individual, antisocial, and self-destructive responses. Economic anxieties caused an upsurge in suicides, and induced growing numbers to seek refuge abroad. Meanwhile, crime, street violence, and looting picked up, discussed in more detail below.

9 The immediate cause of the mass movement that deposed the incumbent president in 2005 was more explicitly political. It centered on anger over Supreme Court appointments viewed as an unconstitutional grab for power. However, fueling the anger that drove tens of thousands of protesters to the streets, including women and indigenous groups, was discontent with the government's neoliberal agenda.

10 Prices in Nicaragua surged even more than in Ecuador.

11 Other protests across the country focused on such issues as anger over privatizations, the eradication of coca fields depriving farmers of a livelihood, corruption, and mining company environmental pollution.

12 Personal communication from Cynthia McClintock, November 2004.

13 For references and an analysis of the literature on Latin American squatter settlements, see Eckstein (1990) and the references therein.

14 Latin Americans have protested the unequal provisioning of water, along with price increases of the essential. Bennett (1995), for example, documents the class bases to water provisioning in Monterrey, Mexico, and how protests by poor women pressured the government to democratize access.

15 Although not a protest against the cost of living, Bolivia was further rocked by a union and opposition party led multi-city mobilization for the right to domestic ownership, control, and use of the country's natural gas supply. After violently repressing protesters, the democratically elected president, Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada, was so discredited that he was driven from office. Indigenous people's success in toppling the wealthy and cosmopolitan president gave them a sense of empowerment and racial pride, on which other struggles built that in 2005 culminated with the election of the anti-neoliberal cocalero leader, Evo Morales, president of the country.This was an unprecedented political break with the past.

16 Not discussed here, international immigration, was yet another response. I discuss that option in Eckstein 2002

17 For regional crime data see Portes and Hoffman (2003).

Bibliography

Alvarez, Sonia, Evelina Dagnino, and Arturo Escobar (eds.) 1998. Cultures of Politics, Politics of Cultures. Boulder, CO: Westview Press [ Links ]

Ambruster-Sandoval, Ralph. 2004. Globalization and Cross-Border Labor Solidarity in the Americas: The Anti-Sweatshop Movement and the Struggle for Social Justice. New York: Routledge [ Links ]

Anner, Mark. 2003. "Defending Labor Rights Across Borders: Central American Export-Processing Plants." in Susan Eckstein and Timothy Wick-ham-Crowley (eds.), Struggles for Social Rights in Latin America. New York: Routledge. 147-66 [ Links ] Bennett, Vivienne . 1995 . Politics of Water: Urban Protest, Gender, and Power in Monterrey, . Pittsburgh,PA: University of Pittsburgh Press [ Links ]

Caldeira, Teresa Pires do Rio. 2000. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation, and Citizenship in Sao Paulo. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press [ Links ]

Calderon, Fernando.1995. Movimientos Sociales y Politica. Mexico: Siglo XXI [ Links ]

Centeno, Miguel Angel and Alejandro Portes. 2006. "The Informal Economy in the Shadow of the State." In Patricia Fernandez-Kelly and Jon Sheffner (eds.), Out of the Shadows: The Informal Economy and Political Movements in Latin America. Princeton: Princeton University Press [ Links ]

Cook, Maria Lorena. 1995. Organizing Dissent: Unions, the State, and the Democratic Teachers Movement in . University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. [ Links ]Coronil, Fernando and Julie Skurski. 1991. "Dismembering and Remembering the Nation: Semantics of Political Violence in ." Comparative Studies in Society and History 33 no. 2 (April): 288-337 [ Links ]

Cross, John. 1995. Informal Politics:Street Vendors and the State in Mexico City. Stanford, CA: Stanford [ Links ]

Di Marco, Graciela, Héctor Palomino and Susana Méndez. 2003. Movimientos sociales en la Argentina: Asambleas, la politizacion de la sociedad civil. Buenos Aires: Jorge Baudino Ediciones, Universidad Nacional de San Martín [ Links ]

Durand-Lasserve, Alain. 1998. "Law and Urban Change in Developing Countries:Trends and Issues." In Illegal Cities: Law and Urban Change in Developing Countries. London: Zed Books [ Links ]

Eckstein, Susan. 1988. The Poverty of Revolution:The State and Urban Poor in Mexico. Princeton: Princeton University Press [ Links ]

Eckstein, Susan. 1990. "Urbanization Revisited: Inner-City Slum of Hope and Squatter Settlement of Despair." World Development 18 no.2 (February): 165-81 [ Links ] Eckstein, Susan. 2000. "Poor People versus the State: Anatomy of a Successful Community Mobilization "for Housing in Mexico City" in Eckstein, S (ed.), Power and Popular Protest: Latin American Social Movements. Berkeley: University of California Press. 329-51 [ Links ]

Eckstein, Susan. 2002. "Globalization and Mobilization: Resistance to Neoliberalism in Latin America." in Mauro Guillen et al, The New Economic Sociology: Developments in an Emerging Field. N.Y: Russell Sage Foundation. 330-68 [ Links ]

Eckstein, Susan and Timothy Wickham-Crowley (eds.) 2003a. What Justice? Whose Justice? Fighting for Fairness in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press [ Links ]

Eckstein, Susan. 2003b. Struggles for Social Rights in Latin America. New York: Routledge [ Links ]

Eckstein, Susan. 2003c. "Struggles for Social Justice in Latin America." in Eckstein, S and Wick-ham-Crowley, T (eds.), What Justice? Whose Justice? Fighting for Fairness in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1-34 [ Links ]

Escobar, Arturo and Sonia Alvarez (eds.) 1992. The Making of Social Movements in Latin America: Identity, Strategy, and Democracy. Boulder, CO:Westview Press [ Links ]

Foweraker, Joe. 1993. Popular Mobilization in Mexico: The Teachers' Movement, 1977-1988. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [ Links ]

Foweraker, Joe and Todd Landman. 1997. Citizenship Rights and Social Movements: A Comparative and Statistical Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press [ Links ] Garreton, Manuel Antonio. 1989/2001. "Popular Mobilization and the Military Regime in : The Complexities of the Invisible Transition." in Susan Eckstein (ed.) Power and Popular Protest: Latin American Social Movements. Berkeley:University of California Press. 259-77 [ Links ]

Garreton, Manuel Antonio. 1995. Hacia una nueva era politica: Estudio sobre las democratizaciones. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica [ Links ]

Gonzalez Bombal, Ines, Maristella Svampa and Pablo Bergel. 2003. Nuevos Movimientos Sociales y ONGs en la Argentina de la Crisis. Buenos Aires: CEDES [ Links ]

International Labour Office (ILO). 1990/1998. Yearbook of Labour Statistics. Geneva: ILO. [ Links ]

International Labour Office (ILO). 2004 and 2005. Labor Statistics. ILO, Bureau of Statistics. http://laborsta.ilo.org/public. [ Links ]

James, Daniel (ed.) 2003. Nueva Historia Argentina.Vol. 9. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana [ Links ]

Jelin, Elizabeth (ed.). 1985. Los nuevos movimientos sociales. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de America Latina [ Links ] Jelin, Elizabeth (ed.). 1995. "Strikes in ," Latin American Research Review 31 no. 3: 127-50 [ Links ]

Márquez, Francisca. 2004."Margenes y ceremonial: Los pobladores y las políticas de vivienda social en Chile." Revista Política de la Universidad de Chile 43: 185-203 [ Links ] McGuire, James. 1995 "Strikes in ."Latin American Research Review 31 no. 3: 127-50 [ Links ]

Noronha, Eduardo Garuti, Vera Gebrin, and Jorge Elias. 1998. "Explicacoes para um ciclo excepcional de greves: o caso brasileiro." Paper delivered at the Latin American Studies Association, Chicago, September. [ Links ]

Porta, Donatella della and Sidney Tarrow (eds.) 2004. Transnational Protest and Global Activism. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield [ Links ]

Portes, Alejandro, Manuel Castells, and L. Benton (eds.). 1988. The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries. Baltimore, MD. Johns Hopkins University Press [ Links ]

Portes, Alejandro and Kelly Hoffman. 2003 "Latin American Class Structures: Their Composition and Change during the Neoliberal Era." Latin American Research Review 38 no. 1: 41-82 [ Links ]

Portes, Alejandro and Bryan Roberts. 2005. "Free Market City." Studies in Comparative International Development 40 (1): 43-82 [ Links ] Ros, Jaime and Nora Claudia Lustig. 2003. "Economic Liberalization and Income Distribution in : Losers and Winners in a Time of Global Restructuring." in Susan Eckstein and Timothy Wickham-Crowley (eds.), Struggles for Social Rights in Latin America.New York: Routledge. 125-46 [ Links ]

Scott, James C. 1976. Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Tironi, Manuel. 1995. Nueva pobreza urbana: vivienda y capital social en Santiago de Chile, 1985-2001. Santiago: Universidad de Chile y Ril Editores [ Links ]

Tokman, Victor. 1995. "Generación de empleo y reformas laborales," Anuario Social y Politico de America Latina y El Caribe (Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) 1: 151-58 [ Links ]

Walton, John. 1989/2001. "Debt, Protest, and the State in Latin America." in Susan Eckstein (ed.). Power and Popular Protest: Latin American Social Movements. Berkeley: University of California Press. 299-328 [ Links ]

Walton, John. 1998. "Urban Conflict and Social Movements in Poor Countries: Theory and Evidence of Collective Action," International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 22 no. 3: 460-81 [ Links ]