I. INTRODUCCIÓN

Development has represented a fundamental goal for democratic states from the beginning of the 20th century. This quest for development represents an increase in the quality of life for a greater number of people. So it can be implied development is the main objective of a democratic State. In fact, democracy is essential to obtain equitable and sustainable development, through the strengthening of institutions and the implementation of effective public policies (Payne et al., 2006).

During the last decades, Mexico has advanced in democratic development. The country now holds free elections which have developed civil and political freedoms. Democratic development could be considered a challenge for the government and the entire society (IDD-Mex, 2021). Although, in 2020, Mexican democracy had been affected by COVID- 19, at least considering the citizen perception, where according to Latinobarómetro (2021), only 43% of Mexicans prefer democracy to any other type of government system and 33% are not satisfied with democracy in Mexico, and the remainder of Mexicans being indifferent (26%). These statistics are a sign of disapproval from Mexican citizens. The circumstances of the pandemic have only exacerbated a problem that has already existed in recent decades.

In addition, COVID-19 has had a negative impact on the economic development in Latin America, this is the same region in which Mexico resides. Indeed, Latin America has 8.4% of the world’s population but has presented 18.5% of all cases and 30.3% of the deaths worldwide (ECLAC, 2021). Furthermore, Latin America in terms of economic activity and unemployment is the most affected area. Particularly according to ECLAC (2021), Mexico in times of the pandemic has faced a decrease of 7.7% in GDP and an increase of 9.5% in unemployment.

Therefore, if COVID-19 has affected the democratic and economic development in Mexico, the main question emerges. What is the relationship between economic development and the level of democracy in Mexico in times of the pandemic? In order to answer this question, it is necessary to analyze the performance of economic development and the behavior of the level of democracy during 2019 and 2020, where the indicators used will be the Social Progress Index (SPI) and the Democratic Development Index (DDI), respectively.

This research aims to find the relationship between the level of democratization and the level of economic development in Mexico, specifically in the year of COVID-19. This study allows increasing the knowledge related to some problems derived from the global pandemic situation.

First, the main previous findings between the relationship of economic development and the level of democracy are shown. Subsequently, the indicators used in this research are described. Consequently, the methodology is explained. Following the found results with the regression analysis and finally, the conclusions are disclosed.

II. DEMOCRACY AND ECONOMY

There is no single consensus on the causality of the relationship between the level of democracy and economic development, even this relationship could be considered as an example of the chicken and egg problem (Brieger and Markwardt, 2020). However, all the hypotheses have been developed from the classic “modernization hypothesis” (Lipset, 1959), in which the level of democracy is associated with the level of economic development. In fact, the level of democratization increases with economic development.

As stated by Diamond (1992), Lipset’s hypothesis was the starting point for all future work on the relationship between the political system and economic development. Nevertheless, considering the level of democratization as an independent variable, there are two views according to Brieger and Markwardt (2020), the consensual view and the critical view. In the consensual view, democratization has a positive impact on economic development, that is, democracy and the economy are positively related. In the critical view, democratization reduces or does not affect economic development, in other words, democratic development does not improve the economy.

The consensual view has been confirmed by Persson and Tabellini (2009) with world data from 1800 to 1994. As a conclusion it has been established that greater democratic percentages are associated with greater economic growth due to the increased stability of democracies, where democratic capital has been measured and compared with the historical experience with democracy by country.

There are several studies that have carried out an analysis in order to identify the relationship between the type of government system and economic development. The type of system could influence economic growth directly or indirectly, democracy does not arise as a consequence of economic development, but empirical patterns indicate that democracy is more fragile in countries where income per capita declined (Przeworski, 2004).

Furthermore, Gerring et al. (2005)) have analyzed whether the type of government regime is associated with the economic growth of a country, classifying the type of system of government as democratic and authoritarian. The conclusion has been that the type of governance affects the economic performance of a country, where democracies are associated with both positive and negative elements, even in some cases will cause a completely negative effect, while many authoritarian governments have become enormously rich, concluding that democracy is a luxury that only rich countries can afford. On the other hand, Rodríguez-Burgos (2015) has studied the problems associated with the democratic transition of countries as a consequence of observing the positive relationship between the level of economic development and the democratic system.

Thereby, there are studies that present a positive relationship between economic development and democracy, but the main finding is that the level of economic development causes the level of the democracy. Instead, democracy does not cause economic development (Huber et al., 1993; Burkhart and Lewis-Beck, 1994). Another special finding has been the effect of economic development on electoral democracy due to the reduction of electoral fraud, electoral violence and vote buying (Knutsen et al., 2018).

Although there are several studies with evidence that show the existence of a positive relationship between the level of democracy and economic development, there are other studies that have not found enough statistical evidence. In Latin America, a relationship between economic development and democracy to the regional level has not been found, even considering control factors for sub-regional variation (Landman, 1999). At the international level, there is no evidence that economic development has a causal effect on democracy (Robinson, 2006). However, per capita income and democracy are correlated, since the very characteristics of a society simultaneously determine how prosperous and how democratic it is.

Other studies have been carried out to understand the relationship between democracy and economic variables in a broader perspective. Regarding economic inequality, Birdsall, Lustig & McLeod (2011) have studied the development of Latin America in the period 1990-2008, finding that the democratic systems in the area have reduced inequality due to structural changes. In contrast, populist governments have failed to diminish them. Additionally, they determined that democratic administrations not only designed more redistributive social policies, but also maintained a steady macroeconomy.

Another study that has analyzed the relationship between political variables and economic development in a country has been carried out by Radu (2015), where Eastern European countries are analyzed using political freedom, political stability and political security as variables of the political environment. All of these political determinants have been found to have an impact on GDP. In fact, political security is positively associated with the level of education and the level of investment. Regardless of the type of government, which is surely implicit, some studies have emphasized the different degree of incidence of a political party in certain economic variables. In the Balkan countries, it has been indicated that there is a political party effect on economic policies, specifically on fiscal policy, Sweden and Norway, respectively (Pettersson, 2007; Fiva et al., 2013). But there are also studies that indicate that there is no evidence of the impact of political parties on economic policies (Ferreira y Gyourko, 2009; Gerber y Hopkins, 2011; Acuña et al., 2019).

In this research, the hypothesis which will be tested statistically is the consensual view, where the level of democracy has a positive impact on economic development.

III. INDICATORS OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND LEVEL OF DEMOCRACY.

This section represents the description of both variables used in the research, economic development and level of democracy. Therefore, the section shows the SPI and the DDI, respectively.

Economic development.

Development is a way of defining the success of a society, according to Imperative of Social Progress (2019). The concept of development is closely related to modernity, which consists of the conviction that earthly existence itself can become an increasingly ideal or superior, and is determined by internal forces whose development constitutes the logic and essence of development (Rojas, 2012).

Development can be represented as a journey from what is considered something inferior, to something considered superior, since it represents an improvement in living conditions, and is associated with a specific space and time, hence the meaning of development can vary depending on the place or time in which it is evaluated (Rojas, 2009). Besides, Porter et al. (2013) defines social development as the ability of a certain society to satisfy the basic human needs of each of its citizens, establishing the construction of platforms that allow communities to improve and sustain the quality of life, as well as the creation of the conditions for all individuals to reach their potential.

The OECD (2006) establishes that the development of a society can be seen as the quality of life, well-being, or sustainability, so quantifying development solely through economic activity can lead to a wrong perspective. There are different ways to measure development but it is clear that a development indicator must not only contain economic variables, instead must also include political, educational, health, safety, and environmental variables (Estes, 1984). Moreover, the United Nations has been adjusting and improving the approach to understanding social development. For this, they initially developed the Human Development Index (HDI), which was used to monitor the development of nations, although today different types of indicators derived from the HDI are identified.

Beyond measuring the HDI, other institutions have also sought to quantify development. One of the most recognized worldwide is the Social Progress Imperative organization, which since 2013 measures the social and environmental performance of countries, for which it publishes the SPI. This SPI methodology includes four basic principles, social and environmental indicators, indicators of results and not performance, relevant indicators for the context, and indicators that may be the objective of public policies or social interventions.

The SPI incorporates the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), proposed by the United Nations (UNDP, 2018). These indicators are used to quantify the development of a society, they represent the main objective in political speech. Also to justify the actions of making decisions in the elaboration of public policies, as well as in international organizations (Rojas, 2009). The SPI is made up of three dimensions, basic human needs, well-being and opportunities, which are made up of twelve components of development, related to concepts such as access to basic services, information services, and elective services, respectively. Each of the components is represented by variables that reflect its current situation (México, ¿cómo vamos?, 2019).

Since its pioneering studies, the Social Progress Imperative organization has found empirical evidence of the positive relationship between social development and economic growth. For the year 2019, it has found a significant and positive relationship between the SPI and gross domestic product per capita (GDP), denoting a direct connection between them, although it should be noted that this relationship is a non-linear relationship, where low- income countries show a large increase in social development due to small differences in GDP per capita. While in high-income countries, small differences in GDP per capita are associated with small increases in social development. On the other hand, it is possible that GDP per capita cannot be the only explanatory variable of development (Social Progress Imperative, 2019). In SPI 2019, Mexico ranked 55 out of 149 countries in the world. The countries positioned in the first place are Norway, Denmark, Switzerland, Finland, and Sweden. In SPI 2020, Mexico ranked 62 out of 163 countries in the world. The countries best positioned are Norway, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand and Sweden.

Since 2019 the version of the SPI for Mexico has been created as an independent indicator of social development to complement GDP and to encourage political leaders, social interest groups and academics, which was created to develop and implement systematic and structured approach that promotes inclusive growth (Mexico ¿cómo vamos?, 2019). The SPI has been elaborated by the organization called “Mexico, ¿cómo vamos?” in collaboration with Social Progress Imperative, which represents a group of researchers consisting of academics and experts in Mexican economics and public policy.

The SPI defines three dimensions within its methodology, basic human needs, well-being and opportunities. Each dimension has four components, which are intended to measure social development. Unlike the international SPI, which uses 51 indicators, the national one used 58 indicators, obtained from official sources of information, public institutions and technical public entities, as well as non-governmental organizations.

Each indicator is interpreted as the higher the value, the greater the social development. The SPI has a scale from 0 to 100, and is obtained from the simple average of the three dimensions. Each dimension represents a scale from 0 to 100, and is calculated as the simple average of its four components. The 58 indicators can be found in the Exhibits of this document. As with the SPI at the international level, the SPI at the national level, a significant and positive relationship has been estimated between social development and GDP per capita, which shows that both elements are closely related. In addition to the above, a positive relationship has been found between the SPI and the HDI, so both tools can complement each other in a proper way. Also, it has determined the presence of a significant and negative relationship between the SPI and the level of poverty in each State in Mexico. This research will be carried out by considering economic development variables to the quantification by the SPI.

Level of democracy.

In this research a non-binary variable has been used in order to identify the degree of democracy in a region. Like any other social fact, democracy works with arbitrary values. Beyond quantification to pursue a precise irrelevance (Sartori, 2004), measuring the level of democracy makes it possible to advance in the construction of the democratic development of a region.

Quantification allows a critical debate, promotes social mobilization and helps articulate social issues and put them on the government agenda, even adding issues that previously disappeared (Kurunmaki et al., 2016; Demortain, 2019).

Measuring the level of democracy should be an approximation of the ideal of life. It should indicate the difference between the ideal and the real level. Always considering the public perception. The final result incorporates a diversity of variables and factors associated with the region. Structural factors such as economic inequality, institutional factors such as the party system and sociocultural factors such as social capital (Rivas, 2015).

One of the most important quantifications of democracy in Latin America is provided by Latinobarómetro, a non-profit corporation based in Chile, financed with funds from multiple international organizations, countries and private funds, who carry out surveys to estimate the level of democracy. These surveys include questions about preference for the type of government, support, perception, rejection and satisfaction with democracy (Latinobarómetro, 2021).

But in this research the Democratic Development Index (DDI) will be used in order to measure the level of democracy in Mexico, which has been prepared since 2010 by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, PoliLat Consulting, Center for Political and Social Studies, National Electoral Institute (INE) and the Confederation of Social Unions of Entrepreneurs of Mexico.

The objective of DDI is to contribute strengths and weaknesses in the Mexican democratic development path and to evaluate the behavior of democracy for each State of Mexico. It consists of 24 indicators and includes four dimensions of democracy, citizen, institutional, social and economic democracy, which represent the citizen rights, institutional quality, conditions related to social and human development, economic opportunities and equity. The 24 indicators can be found in the Exhibits of this document (IDD-Mex, 2021). Hence, the level of democracy will be calculated from the DDI.

IV. METHODOLOGY AND DATA

The purpose of this study is to determine if the level of democracy can be related with a certain level of economic development. For this, the SPI will be used as a variable of economic development. On the other hand, DDI will be employed as a variable of level of democracy. The data used includes each of the 32 States of Mexico, for the period of 2019 and 2020. This data will be taken from the organization called “Mexico, ¿cómo vamos?”, the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, PoliLat Consulting, Center for Political and Social Studies, National Electoral Institute and the Confederation of Social Unions of Entrepreneurs of Mexico.

Then, the variables for this research will be the SPI and the DDI for the period 2019-2020 in order to let us observe the changes that the global pandemic situation originated from. Particularly, the model that will be tested is the model (1).

Where SPI represents the growth rate between 2019 and 2020 for economic development measured through the SPI, DDI is the growth rate between 2019 and 2020 for the democratic development calculated through the DDI and it indicates the State of the country.

Also, the model (2) will be tested, in which dimensions are incorporated both to SPI and to DDI. This model will be calculated three times, each one of them to estimate the effect of the dimensions of democracy on each one of the three dimensions of economic development.

Where j represents each dimension of the SPI, these dimensions are basic human needs, well-being and opportunities. Besides, CDI is the citizen democracy index, IDI the institutional democracy index, SDI the social democracy index and EDI the economic democracy index and i indicates the State of the country.

Consistent with the hypothesis, the proper statistical analysis will be a regression analysis, where sufficient statistical evidence will be found to infer that economic development is related to the level of the democracy. The analysis is performed using the E-Views statistical package.

V. RESULTS

This section is divided into descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. The first part shows the changes in both SPI and DDI between 2019 and 2020. The SPI is used to contextualize the data and the impact of the COVID-19 on these indicators. In the second part, statistical analysis through a linear regression is used.

The impact of COVID-19.

Evidently, COVID-19 has affected every economic indicator worldwide, but it is fundamental to know the variation in percentage terms because it lets us compare between 2019 and 2020 data. Also, if there is quantification, it could be evaluated and understood.

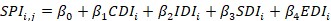

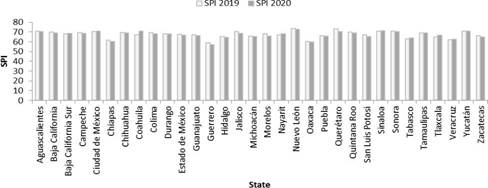

In Figure 1, it can be seen the average SPI by State which represents the variable of economic development. There is a clear difference between 2019 and 2020 data. Most States have experienced a reduction of SPI during the year of COVID-19. The average change is equal to -0.65%, where only 11 out of 32 States have increased their SPI. Coahuila is the State who had the greatest progress. Instead, Queretaro is the State with the worst performance. Both in 2019 and 2020, Nuevo León is the State with the highest value of the SPI, with 73.85 and 72.76, respectively. While the worst positioned state in both years was Guerrero with 58.86 and 56.84, respectively. In general terms, the average of SPI 2019 in Mexico was 67.63 and 67.18 in 2020, which reveals the negative impact on economic development due to COVID-19.

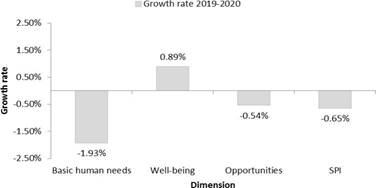

Figure 2 shows the annual growth rate of each dimension of the SPI, where the dimensions of basic human needs and opportunities have been decreasing between 2019 and 2020. But the dimension of well-being has increased in this period.

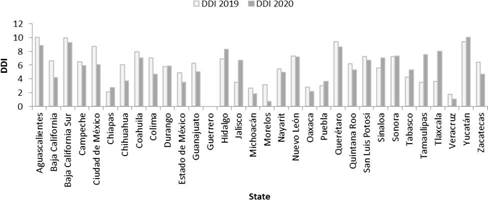

In Figure 3, the SPI can be observed individually in each State between 2019 and 2020. Considering the average annual variation, the DDI has changed in -0.22%, which it is a consequence of the impact of COVID-19. As well as the SPI, only 11 States out of 32 presented an increase on the DDI. Tlaxcala is the State who obtained the greatest progress. But the State with the worst performance was Morelos. Aguascalientes had the highest value of the DDI in 2019 and in 2020 was Yucatan. While in both years, the lowest values were obtained by Guerrero. Evidently, the negative impact of COVID-19 on democratic development was clear, where the DDI went 5.66 from to 5.43.

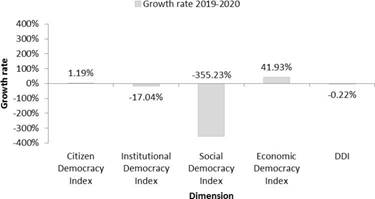

Figure 4 represents the annual growth rate of each dimension of the DDI. The dimensions of institutional and social democracy were negatively affected during the year. Instead, the dimensions of citizen and economy had an increase in the year.

The relationship between economic development and democratic development.

In this section, the regression analysis will be carried out in order to estimate the relationship between economic development and democratic development. Particularly, the consensual view has been tested statistically, which was emphasized in the literature review.

In Figure 5, the relationship between the variables used in this research could be seen. The variables are represented in growth rate. This graph starts indicating the positive relationship, but it will be tested statistically.

In the regression analysis, both SPI and DDI are considered as a growth rate, as well as each dimension. In other words, the relationship will be found regarding the behavior between 2019 and 2020.

Table 1 Results of regression analysis.

| SPI | Basic human needs | Well-being | Opportunities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Coefficient | ||||

| DDI | 0.010711 (0.008270) | - | - | - | |

| CDI | - | -0.009942 (0.013080) | 0.001334 (0.010739) | 0.009086 (0.008803) | |

| IDI | - | 0.093014* (0.031703) | -0.032177 (0.028294) | 0.026760 (0.020271) | |

| SDI | - | -0.000106 (0.000317) | -0.000153 (0.000174) | 0.000698* (0.000142) | |

| EDI | - | 0.001493* (0.000520) | 5.63E-05 (0.000669) | 0.000411 (0.000731) | |

| R2 | 6% | 20% | 2% | 19% | |

Source: Authors based on Mexico ¿como vamos? (2019, 2020) andIDD-Mex (2019,2020) data. Note: * indicates that p-value< 0.01. Standard error in parentheses.

Table 1 describes the results obtained considering the regression analysis for model (1) and (2), where model (2) corresponds to each dimension of the SPI. The model (1) represents that the relationship between economic development and democratic development is positive. However, this result is not significant. Instead, when each dimension of the SPI is considered as a dependent variable, certain dimensions of the DDI are significant. The main finding is that each dimension that has significance always has a positive coefficient. In other words, there is enough statistical evidence to determine that democracy has a positive impact on economic development.

Tests have been performed to test the assumptions of the linear regression model, such as homoscedasticity, no autocorrelation and normality. Also, the goodness of fit of the model reached up to 20% according to r-squared, an adequate value since it represents the proportion for a dependent variable that is explained by an independent variable and considering that the SPI is made up of 58 indicators and de DDI of 24 indicators. It can be concluded that the model ensures compliance with the classical assumptions of the linear regression model.

Therefore, the main finding is that democratic development represents a differential element in the economic development achieved by a State in Mexico, although not all the results are significant.

Figure 6 simplifies the results obtained with regression analysis, where the democratic development has a positive effect on economic development. Both institutional democracy index and economic democracy index have a positive relationship with the dimension of basic human needs. Also, the social democracy index and the dimension of opportunities are directly related.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Interesting findings have been obtained that have not been analyzed in depth in other investigations. In this research, a regression analysis has been carried out in order to find the relationship between the level of democracy and economic development.

It has been found that the democratic progress has a positive effect on economic development in Mexico, in times of a global pandemic, where both democratic and economic development were affected by COVID-19 since both SPI and DDI have declined in 2020. In other words, the level of democratic development represents a determining element in the economic development of Mexico. Hence, according to the consensual view, the hypothesis has been accepted.

The results could be a sign of how democratic structures impact on stability because this creates less uncertainty, thus promoting investment and growth (Persson and Tabellini, 2009). Even, the results could be explained due to the persistence of a democratic administration that tends to foster different types of capital, physical, human, social and political (Gerring et al., 2005).

Beyond the possible cause of this association, the results shown here represent a way to guide public policies aimed at strengthening the level of democracy in Mexico, which will have repercussions on the economic development of the country.

Therefore, it is essential to invest in democratic progress, whether in guaranteeing political rights and citizen freedoms or in promoting citizen participation, gender policies and transparency or combating corruption, since this in turn will generate a positive effect in the Mexican economy.

The incorporation to another variable, like the political party or the ideology of the political party through a spectrum right-left could be carried out in the future to generate more knowledge about this relationship. Additional investigations can verify these results at a municipal level in Mexico, considering some approximate variables of both components SPI and the DDI.