Introduction

It was the first pedagogical meeting of the year. We, as teachers who worked at the English department of a language center from a Federal University in Brazil, had certain autonomy to make decisions concerning the functioning of the classes and the structure of the courses. One of the topics of discussion that day was assessment. At that time, there was a test called “Progress Check” (Appendix 1) that was applied twice in each course, once in the middle and once at the end of the course. The purpose of this test was to evaluate1 students’ knowledge of the grammar structures we worked on during the semester. Thus, every test was full of “fill in the blanks” and “unscramble the words” exercises.

Some teachers, the authors of this paper included, felt that the test was unnecessary. Our arguments usually relied on the fact that there were already many tests. Indeed, besides the Progress Check, there were four other tests, focusing on speaking, writing, reading, and listening skills, which also happened twice every course. In addition, the grammar test had an extremely artificial and mechanical approach to language. Finally, some more rebellious teachers argued that the dislocated evaluation of grammar was a waste of time and energy.

There were, of course, advocates of the Progress Check. According to them, there was no way to identify whether or not students were learning if it was not for the grammar test. For these teachers, this type of assessment was necessary to motivate students to learn and review the information about grammar. To quote one of them loosely, “students will only study if they have a test to take”. For these teachers, therefore, the purpose of having a test is to make students study. The discussion went on and eventually we decided to remove the grammar test from all English courses.

To evaluate or not evaluate grammar knowledge during language courses is already a complex question to address, be it in a separate test, such as the Progress Check, or during the assessment of other skills, such as writing and speaking. Nevertheless, what strikes us the most about this short narrative are the statements made by the teachers regarding the purpose of the evaluative process. It seems as though they consider evaluation as the target of learning. Teachers and students spend weeks working with topics so they can have tests at the end and obtain a good grade. In other words, there is a view of learning for assessment.

This idea, however, has never sat comfortably with us, the authors of this article. During our practices, in our separate classrooms, we have been problematizing and trying to move away from this “teaching to evaluate” mentality. Our paths crossed in 2020, when we sat down to discuss possibilities to assess our students in the new courses we were structuring and we realized we had similar preoccupations. One of our main concerns was to come up with an evaluation that would allow students to learn with and not for. In this paper, we will not only problematize assessment and its purpose, but also try to propose possibilities otherwise. For Mignolo and Walsh (2018), otherwise means unlearning and stepping aside from the modern/colonial hegemonic paradigm and its beliefs and exploring different possibilities of being, knowing and doing. Thus, we want to explore an evaluation otherwise and promote a more critical and democratic linguistic education.

Since our goal is to break away from traditional concepts of language, knowledge and assessment, we will follow the movement proposed by authors such as Diniz de Figueiredo and Martinez (2019) and elucidate some points concerning our loci of enunciation before moving on to the next sections of the article. According to Grosfoguel (2011), the locus of enunciation is “the geo-political and body-political location of the subject that speaks” (p. 6). So here is ours: We are two Brazilians -one female and one male, both white and in our late twenties- working with ELT in Brazil. We are also students in an Applied Linguistics graduate program. At the time of the research, Camila was a PhD candidate and João was pursuing his master’s degree. In our studies, we have been problematizing ELT through critical perspectives on linguistic education (Duboc, 2019; Freire, 1987; Jordão, 2019; hooks, 1994; Menezes de Souza, 2011;), epistemologies of the South, and decolonial lenses (Grosfoguel, 2011; Jordão et al., 2020; Mignolo, 2021; Mignolo & Walsh, 2018).

We teach English in a language center from a federal university, where courses are paid for by students. The majority comes from the university, but the general public can also enroll. It is possible to state that we are working in a context of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) for two main reasons: first, because English does not have an official status in our country. Secondly, because EFL has become an orientation of teaching in Brazil, marked by normativity, standardization and the native speaker model (Duboc & Siqueira, 2020). In spite of that, given that we teach within the walls of a federal university, we have some wiggle room to explore more liberating conceptions concerning our practices.

Since we want to position ourselves against traditional hegemonic beliefs concerning language teaching, we opt for decoloniality. We understand this movement not as a mission, but as an option for us to move towards a praxis otherwise. Therefore, after realizing that we both had had previous experiences with alternative modes of evaluation on our own, in 2020, we decided to join efforts for the first semester of 2021. The idea was to use our freedom to promote an assessment that broke from the traditional models we had been following up to that point.

In the following section, we address the readings that give basis to our reflections and problematizations. Next, we explore in detail the evaluative projects we conducted in our classes and how they were assembled alongside our students. We also delve into comments made by the participants and explore our own impressions and memories of the experience. Finally, in the fifth and final section of the paper, we propose the notion of avaliar se avaliando (evaluate oneself evaluating) as an option to promote an assessment otherwise.

Questioning Assessment

Considering our context of teaching English in Brazil, in this section, we reflect upon the concepts, assumptions, and premises that ground language teaching and assessment. Also, since our desire is to promote a critical and more democratic linguistic education, we problematize the notion of assessment and analyze how different it is from what we believe it should and could be.

Traditional Concepts of Knowledge, Learning and Language

Questions such as what, how, and why we assess, are (or at least should be) answered based on our epistemological positions, i.e., our concept of knowledge. Duboc (2007) notes that, in its foundation, the traditional schooling evaluation system was strongly influenced by positivism, prioritizing rational and logical observation of stable facts. In the second half of the 20th century, there was a movement, led by authors such as Vygostky, Dewey, and Montessori, towards a social constructivist orientation, which perceives knowledge as socially and historically constructed. Despite this movement, our experiences as well as our readings tell us that the positivist perspective still prevails. Indeed, both Martinez (2014) and Jordão (2014) highlight how most practices in the classroom still reflect the conception of knowledge as something measurable and external to subjects.

One of the possible reasons for the prevalence of this positivist view is the colonial project (Grosfoguel, 2011) since it advocates for the idea of Western scientific knowledge as superior. According to Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel (2007), the Enlightenment deemed other knowledges as inferior, excluding and silencing everything that did not come from the European elite. In addition to this supremacy of the North, coloniality consolidated rationality and logic as the center of science (Jordão, 2019), excluding body, emotions, subjectivity, and everything considered non-observable or quantifiable.

These dominant concepts influence the next notions we would like to explore: those of teaching and learning. From a colonial, modern, and positivist standpoint, there are universal truths that can be transmitted by teachers and assimilated by students, something Freire (1987) called “banking education”. In it, students assume a passive position and learning becomes a synonym of assimilation of things, data, and facts. What is the purpose of assessment in this educational model? To verify the mere apprehension and reproduction of these things in an objective and stable way (Duboc, 2019). As explained by Jordão (2014), there is an illusion of control and a belief that grades can attest to what and how much students have learned.

In sum, concepts of knowledge and learning have historically influenced how we see and do assessment. The dominant paradigms tend to be the ones that privilege a positivist view, characterized by summative, objective, controllable and measurable results. Besides, the language school is, undeniably, one of the many powerful institutions which contribute to reproduce and serve these colonial values. Since our aim is to analyze assessment specifically in this context of ELT, let us move on to consider the following question: what discourses on language are being perpetuated through assessment of English in Brazil?

Recently, much has been discussed about language in our globalized society and its transcultural movements. Post-structuralist theories, for instance, take language as a social practice, as a fluid and open system, rather than a closed one, as suggested by Structuralism (Jordão, 2006). However, it is the structuralist perspective that corresponds the best with the positivist, modern, and colonial mindset. Canagarajah (2013) enumerates the main characteristics of language according to this perspective: (a) every language is connected to a community and a place; (b) it corresponds to an identity; (c) it is an autonomous system, pure and separated from one another; (d) it is a cognitive process; (e) it is based on grammar rather than practice and its form is isolated from contextual and social space.

Regardless of all alternative research on how to look at communication, modern, colonial, and structuralist ideologies that privilege Western interests have been the ones orienting the field of ELT. What are the consequences of this for assessment? Essentially, language becomes measurable based on the structuralist standpoint of a series of stable rules, which are in turn based on the uses of native speakers (Shohamy, 2011). Also, there is a prevalence of a monolingual stance that views different languages as separate units, with the penalization of students when they deviate from the norm or mix languages (García & Ascenzi-Moreno, 2016).

Our own experiences as English teachers corroborate these characteristics in all kinds of spaces: the contexts with which we are familiar, textbooks, methodologies, market discourses, and, certainly, assessment practices. For instance, objective or short-answer tests are the main tool to evaluate; assessment is considered a synonym of measurement given the importance of numerical grades; and most criteria used by teachers are based on structuralist notions and the model of the native speaker. Hence, assessment has mainly reinforced a monolithic and structuralist view of language by delegitimizing certain uses and meanings, imposing norms that are usually oppressive and/or irrelevant to learners’ contexts, and precluding them from exploring their own repertoires. In the next section, we explore these consequences and effects a little further.

Material Implications for Teachers and Students

Why are we trying to move away from this colonial and modern tradition in ELT? First of all, when assessment reinforces language as a closed system which belongs to certain privileged people, it promotes structures of social and linguistic violence and oppression which become visible in the relation students develop with English. First, it is possible to observe that speakers feel material impacts (Haus, 2021), such as the silencing of their repertoires (Vogel & García, 2017), feelings of imposture and insufficiency (Kramsch, 2009), cultural assimilation, academic and professional pressure, and linguistic/racial prejudice (Kubota, 2012), among others.

Secondly, as Duboc (2019) states, assessment as a way to control results and measure learning becomes both an operation of exclusion and punishment, and an instrument of “disciplinamento e normatização de discursos, corpos, tempos, espaços, comportamentos” [discipline and standardization of discourses, bodies, times, spaces and behaviors] (p. 136)2. This is extremely visible in the context we presented in our introduction, where teachers stated that tests are necessary in order to “make students study”, or to “identify whether or not they had learned”.

Finally, another implication that is actually intrinsic to all the implications previously mentioned is the one related to emotions. What feelings do these types of assessment evoke? In fact, as we have stated earlier, this “modern/colonial capitalist/patriarchal world-system” has as one of its foundations the Cartesian thought of “ego-cogito”, which produced the binaries: mind-body; reason-emotion (Grosfoguel, 2011). We stand with Hooks (1994) when she asserts that, in the classroom, this split promotes and is reinforced by the objectification of the teacher, leading both teachers and students to be fearful that the self could be an interference; and to disconnect life, habits and emotions from their teaching and learning experiences. Faced with this scenario and the need to challenge this modern/colonial rationality, we have to recognize that emotions play an important role in the way we establish relationships and make meanings with/of the world (Jordão et al., 2020).

The emotions triggered by assessment as problematized by us are several. On the one hand, we witness students that feel insecurity, fear, anxiety, pressure, and tension. On the other hand, we have teachers who, due to the belief that contents should be verified objectively, embrace the illusion that they can ignore their own feelings and subjectivity. When reflecting upon Ahmed’s theory (apud Benesch, 2012) of “sticky” objects, i.e., objects that have specific emotional responses attached to them, Benesch (2012) asks teachers and researchers to question what emotions stick to certain objects and how these findings can inform their teaching. If we consider assessment practices as sticky objects, we may legitimize students’ relationship with them as “unhappy objects,” and recognize how the subjectivity of teachers is intrinsic to the process. This can be an opportunity to make room for questioning, and consequently, for exploring other assessment practices.

In accordance with Benesch (2012), our goal here is not to state that certain emotions are positive and others negative. Instead, considering our context of ELT and our belief that learning a language “makes these students more conscious of their bodies (emotions, feelings, appearance, memories, fantasies)” (Kramsch, 2009, p. 30), we would like to promote assessment practices that allow other emotions to appear and be explored, such as affection, confidence, self-knowledge, belonging, fun and authenticity. Beyond the emotions usually associated with traditional forms of assessment, we believe that these other feelings may impact the learning process insofar as they affect students’ affinities with the language, the teacher, and their classmates. Welcoming these emotions in the classroom, may result in the creation of an encouraging, stimulating, and open community which allows learners to explore and transform their knowledges and practices.

Different Paths to Explore

So far, we have been problematizing dominant assumptions and concepts in ELT assessment. Now, it is time to consider what theories, perspectives, and stances allow us to envision different assessment practices. Considering Duboc’s (2019) idea that there are two possible paths for assessment, the first being one that excludes, labels, and classifies, and the second being one that includes, comprehends, and welcomes students, we have decided to follow the second. The theories we will discuss next are intended to create a base for a practice of formative assessment that moves us closer to this objective.

Other Concepts of Knowledge, Learning and Language

Since the first concept we questioned here was knowledge, let us begin by thinking about it otherwise. Provided we follow decolonial theories, we have to break away from the ideas of the North as universal/superior, the separation between mind-body, and the illusion that this knowledge is created from nowhere/no one. Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel (2007) advocate for a body-politics of knowledge, which admits that all knowledge is produced by bodies crossed by contradictions, different points of view, and epistemologies. According to these authors, there is no point-zero (Castro-Gómez & Grosfoguel, 2007), from where single truths emerge, and therefore an ecology of knowledges (Sousa Santos, 2007) seems more appropriate. This ecology suggests that all meanings are limited and incomplete, giving space to destitute (Mignolo, 2021) and subalternized peoples (e. g. workers, women, racialized, LGBTQIA+) and their voices. In our perspective, instead of being mechanisms that reproduce and reinforce modern and colonial discourses, ELT and assessment practices should allow us to question traditional conceptions by exploring, including, confronting and constructing different knowledges.

Another theory that approaches knowledge differently is critical literacy, as developed in Brazil (Jordão, 2014; Menezes de Souza, 2011). From this perspective, knowledge is a social practice of meaning-making, and every subject is actively producing meanings. Education, thus, should go beyond scientific and academic knowledge, recognizing power relations and hierarchies but making space for these to be questioned and problematized. Agreeing with this, Jordão (2019) emphasizes the need to leave the binaries of reason-emotion behind, conceiving knowledge as always embodied, interactional, procedural, fluid, and unpredictable.

In sum, the fundamental characteristics of critical literacy as an educational approach are: (a) language is seen as a social practice filled with ideologies and power relations; (b) knowledges are considered products of histories/collectives, all are valid, and dissent/conflict between them should be seen as fruitful; (c) recognizing one’s own meaning-making processes, learning to “read oneself reading” i. e. developing self-reflexivity and self-questioning is essential (Menezes de Souza, 2011); (d) teachers and students are supposed to assume the position of authors/producers of knowledges and meanings in the classroom, emphasizing agency.

If we were to keep in mind the above-mentioned premises of decoloniality and critical literacy, what could be the implications for assessment? We may assume language and teaching practices that are open to diverse knowledges. As Haus (2021) states,

ao invés de testes que tenham como expectativa que o aluno produza (ou melhor, reproduza) leituras específicas, [...] a avaliação deveria olhar para a capacidade crítica do aluno de construir sentidos, de observar como esses são construídos no mundo e de que forma ele mesmo realiza esse processo

[Instead of tests that expect the student to produce (or rather, reproduce) specific readings [...], assessment should look at students’ critical ability for meaning-making, for observing how these meanings are constructed in the world and how they realize this process].(p. 157)

Thus, we want to emphasize our stand for an education that moves away from content transmission and for an assessment that breaks with the chains of measurement. Being against the separation between mind-body, we are not afraid to see classrooms as spaces for building affective relations. ELT can and should welcome Freire’s idea of an education that questions and reflects upon conditions of subalternization and discrimination, and has as its final goal the transformation of the world (Freire, 1987). It should also include the Engaged Pedagogy promoted by Hooks (1994), which perceives teaching and learning as a holistic process of mind, body, and spirit. Her work showed us that classrooms can be a space where teachers and students have their expressions valued and, through sharing their narratives and being vulnerable, are able to see how life can transform our understandings.

Lastly, we propose to look at language (in this case, English) and its teaching otherwise. We do so by aligning our thinking with English as a Lingua Franca (ELF), one of several ways through which researchers are making sense of current cross-cultural interactions. This field of research calls into question many assumptions and principles of the structuralist traditions of EFL, such as the role of the native speaker, the centralization of grammar, and the approach to culture. Since elf studies have had various goals, it is important to clarify that we draw on Duboc and Siqueira’s (2020) call for “ELF feito no Brasil”. It is an understanding of elf from the South, based on particular epistemes and ontologies and on a transdisciplinary view, placing “greater emphasis on the critical and political nature of English and the process of learning and teaching the language in the Brazilian context” (Duboc & Siqueira, 2020, p. 301).

In the past decade, this perspective of ELF has been influenced by translanguaging (Duboc & Siqueira, 2020; Haus, 2019; Jenkins, 2020), the second theory we want to highlight. This theory assumes that in real-life interactions, all linguistic and multimodal semiotic resources of each individual are present, regardless of the named language being used (e.g., English). In other words, people have a unique repertoire whose resources are only marked as belonging to one language or another socio-politically (Vogel & García, 2017). Since each repertoire is unique, meaning-making and intelligibility are not ensured by a totally shared or strictly linguistic system, but by the negotiation and strategies that are used in localized and context-specific interactions happening in a multimodal meaning-making process (Kress, 2010). Since elf and translanguaging acknowledge language as a social practice and communication as a negotiation of repertoires, these post-structuralist theories challenge the central position of grammar/structure and of the native as the model/standard. However, scholars in Brazil have highlighted the need not to ignore the political nature of English by frequently reading these theories through decolonial lenses (Albuquerque & Haus, 2020; Duboc & Siqueira, 2020; Rocha, 2019; Siqueira, 2018).

We then go back to the question: What could the implications of adopting these views be for assessment? We believe there are several: first, instead of measuring fixed and monolingual linguistic structures acquired and used by students, assessment would be grounded in social practices (e.g., negotiation strategies and situated performance). Teachers would try to observe the communicative repertoire of students, including their ability to explore, expand and select styles, registers and modes, while reading contexts critically and being open to and tolerant with difference (Haus, 2021). Also, assessment instruments used in the classroom would reflect such goals, and therefore, be practical, interactive, collaborative, and contextualized.

Allowing Other Emotions

As for our goal of thinking about assessment practices that allow other emotions to appear, it seems to us that these theories of decoloniality, critical literacy, elf feito no Brasil, and translanguaging afford some possibilities. For instance, an assessment that does not point to deficiencies or mistakes but to creativity and intelligence has its impacts. Students may feel encouraged, more confident, and curious. In Jordão’s (2019) words,

[h]á mais responsabilidade e emoção envolvidas no uso criativo de uma língua sobre a qual sabemos ter ownership, do que na suposta aplicação de estruturas construídas por outros em uma língua que achamos que não nos pertence [there is more responsibility and emotion involved in the creative use of a language over which we know we have ownership, than in the supposed application of structures built by others in a language that we believe does not belong to us]. (p. 64)

Another example is the possibility of transgression and freedom that comes with translanguaging. There may be pleasure in not following rules, in exploring different meanings (Benesch, 2012), in making one’s voice heard and managing to communicate when one’s strictly linguistic repertoire in English is not enough (Back et al., 2020). Besides, assessment practices that consider translanguaging and elf allow teachers and students to look at interactions with more playfulness, fun, humor, and resistance (Dovchin, 2021). Finally, just by moving away from an assessment that is meant to control, exclude, and punish, we may experiment welcoming, including, and transforming practices, which might provide means and possibilities for other feelings to emerge in the classroom. By doing so, we may also be bringing the body back (Menezes de Souza & Duboc, 2021) to the classroom. Assessment in ELT should empower students to stand in legitimized and authorized positions, as subjects who can language (Maturana & Varela, 1980) and act critically in their contexts.

To sum up, all theories presented above point to a formative assessment. Hence, we propose the idea of learning with assessment, where the latter is an intrinsic part of the learning process, and where teachers and students collaboratively observe and reflect upon their developments and goals in relation to English as a social, ideological, and multimodal practice. From this angle, feedback becomes more important than grades, and movements and changes more important than final results. To exemplify this, let us now move to the next section in which we present a possibility of an assessment otherwise, describe our field research, propose reflections through the students’ comments, and provide our own impressions of this experience.

The Assessment Project

After deciding that we would join efforts to think about assessment otherwise, we began an evaluative project with students taking English 3 and English 5 at a language center for adults in a Federal University in Brazil. We were each responsible for one group and these met weekly on Saturday mornings. According to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), the students’ proficiency level varied from basic (A2) to pre-intermediate (B1). Below, we briefly describe the steps we took with these groups and the criteria we used for evaluation.

Project Steps

During the first week of classes, we asked students if they were open to explore other possibilities of assessment instead of the formal tests to which they were probably used. After they acquiesced, we proceeded to show them the proposal: we wanted them to create booklets addressing different media (music, movies, series, games, and social media) that dialogued with the topics of the textbook units that we were going to study throughout the semester. We opted for this proposal bearing in mind the following aspects: First, the production of a booklet could be an opportunity to work with language as a social and multimodal practice. Second, as a demand from the institution, we needed to connect the assessment project with the textbook, and create opportunities for students to explore its repertoire in a significant way. Finally, assessment is usually done through individual tasks, which are elaborated to identify whether or not students assimilated specific chunks of information. Given the understandings we presented in the previous section, students were put into groups for the project, as we believe that knowledge is constructed in a collaborative way.

Since classes happened via Zoom, the groups were created randomly through the opening of breakout rooms. Camila taught the English 5 course with 9 students, while João had the English 3 course, with 12 students. They were all divided in pairs or trios (4 groups in English 5 and 5 groups in English 3). Each group chose a different type of media so that the topics were not repeated within the same class. Most of the groups remained the same throughout the course, although some had to change their configuration when students dropped classes in the middle of the semester. Also, there was one student who wanted to switch groups because of differences related to commitment and expectations. In this case, we preferred to have a conversation with the students involved and maintain the group. In fact, one of the feedback comments we received was that if the groups had been divided a few weeks later, they would have been able to choose the people with whom they wanted to work. Although this is a relevant point to consider, one of our intentions was to push them to a place where they would have to negotiate their different perspectives, viewpoints, and repertoires. This strategy seemed to have worked as on the self-evaluation forms that we conducted at the end of the course, most of the students mentioned that they considered collaboration as positive and relevant to their learning. For instance:

Eu gostei bastante de trabalhar em grupo com elas (particularmente não gosto de trabalhos em grupo). Mas com a [Colleague] e a [Colleague] foi uma experiência muito boa, pois elas se dedicaram, não precisávamos cobrar um ao outro. [I really liked working in a group with them (I personally do not like group work). But with [Colleague] and [Colleague] it was a very good experience, because they were dedicated, we did not need to ask anything from one another.] (Student 7, English 3, Self-assessment form, 2021)

Para o inglês, trabalhar em grupo é sempre muito mais produtivo, porque podemos dividir as dificuldades.[For English, working in groups is always much more productive because we can share our difficulties.] (Student 2, English 5, Self-assessment form, 2021)

Other relevant moments of the process were when we presented and explored digital tools and platforms, such as Canva, a digital graphic design platform, and Padlet, a digital notice board for teachers and students. We hoped that this could not only help them with the design of their booklets, but also expand their semiotic repertoires, in light of our conceptions of language.

On this matter, one of the students commented:

Trouxe sempre diversas plataformas diferentes para auxiliar no aprendizado e isso é perfeito para não nos deixar acomodados e sempre todo sábado já acordava sabendo que teria alguma surpresinha durante a aula, motiva a participar. [She has always brought diverse platforms to help in learning and this is perfect for not letting us get comfortable; and always, every Saturday, I woke up knowing that there would be a little surprise during class, this motivates participation.]. (Student 4, English 5, Self-assessment form, 2021)

As for the creation of the booklets, we wanted the task to be done throughout the semester, as one of our goals was to provide a formative assessment. With this purpose in mind, we created activities that would help students with the task (e. g. writings and research in class). For instance, in the English 5 group, one of the topics presented in the textbook was vocabulary to describe visual data. Therefore, Camila asked each group to research and produce an infographic about their media to include in the booklet. With this activity, students had the opportunity to practice the language presented in the unit, work collaboratively on the project, exercise reading, and construct multimodal texts.

In the self-evaluation form, students wove comments that made us believe that the projects had met our expectations, given our preoccupation with exploring multimodality and expanding their understandings of language. For example, student 9 wrote:

Apresentar o trabalho em formato de booklet foi uma excelente ideia pois acredito que é uma forma de atrair a leitura das pessoas, uma vez que se pode utilizar inúmeras imagens e diferentes fontes de escrita no corpo do documento. Sempre gostei de focar no design da informação e acredito que é uma forma atrativa para a leitura. Não só eu como os demais integrantes da equipe gastamos um tempo considerável nesse processo para pesquisar informações fidedignas e estruturá-las com as melhores imagens e fontes possíveis.

[Presenting the assignment in booklet format was an excellent idea since I believe it is a way to attract people’s reading, once it is possible to use countless images and different fonts in the body of the document. I have always liked focusing on information design and I believe it is an attractive form for reading. Not just me, but also the other members of the team spent considerable time in this process researching trustworthy information and structuring it with the best possible images and fonts]. (Student 9, English 3, Self-assessment form, 2021)

In other activities, we also gave them time to go into separate groups to talk about the process, organize themselves, and work in the booklets. We believe that by doing so, we transformed assessment into an ongoing process as the classes were happening as we did this, which disrupted the previous practice of separating a day to have students take a test and be assessed objectively in regard to final results and fixed contents. During the self-evaluation for these activities, students conceded that they saw having a procedural evaluation as something positive:

O projeto permite uma avaliação por um período de tempo maior e desta forma possibilita uma maior aprendizagem. [The project allows an evaluation for a longer period of time and thus enables a better learning]. (Student 2, English 3, Self-assessment form, 2021)

Principalmente se tratando de um curso de idiomas, me tirou da zona de conforto que eram as provas normais e tornando a avaliação mais interativa. [because it is a language course, it took me out of the comfort zone that the normal tests provided and made the assessment more interactive]. (Student 9, English 3, Self-assessment form, 2021)

Provas analisam um dia, esse projeto analisa o processo e como fomos nos saindo durante ele. [Tests analyze one day, this project analyzes the process and how we were doing throughout it]. (Student 4, English 5, Self-assessment form, 2021)

Gosto especialmente porque a interação não é artificial e é desafiante. [...] Foi um processo muito democrático, interativo e dinâmico. Isso me leva a me distanciar dos métodos tradicionais de decoreba da gramática e me fez perceber que posso seguir adiante, vendo menos as minhas limitações e mais as possibilidades.

[I like it especially because the interaction is not artificial and it is challenging. [...] It was a very democratic, interactive, and dynamic process. This made me distance myself from the traditional methods of memorizing grammar, and realize that I can move forward, seeing less of my limitations and more of the possibilities]. (Student 6, English 5, Self-assessment form, 2021)

Eu prefiro assim, pois as vezes o test não significa o tanto que você aprendeu no semestre [I prefer this because sometimes the test does not represent how much you have learned in the semester]. (Student 7, English 5, Self-assessment form, 2021)

In these comments, what called our attention the most was how the students perceived tests as tools to analyze specific moments, which did not represent what they had really learned. Students seemed to realize that they could learn with assessment, and deem the movements and changes that they endured during the process more relevant than the goals and final results. Nevertheless, given the fact that the institution required grading at the end of the course, we decided to promote a reflection about the evaluation criteria so that students could have a say on how they were going to be graded. We present this step in the following subsection.

Criteria for Evaluation

At one point during the semester, we asked students what was important to them about evaluation. Then, we showed them a video clip from the TV special “There’s No Time for Love, Charlie Brown” (E-joy English.com, 2022), in which the characters discussed why they studied. The scene problematized the idea of learning only to get good grades and move on to the next stage of our educational and professional careers and that this is a mechanical and endless process. In order to have a bridge for the discussion about the differences between grades and feedback, we asked students what the irony behind the video was. Next, we reminded students about their evaluation being related to the creation of the booklet and opened presentations using interactive presentation software Mentimeter, in which they could send comments on the elements that they believed should be assessed. Our task as teachers, then, was to organize all of their thoughts into evaluation criteria. We divided their statements into three categories. The first two were labeled Process and Booklets, encompassing elements such as participation, collaboration, information design, quality of the images, connection with vocabulary from the textbook, expansion of their linguistic and semiotic repertoires (which they have referred to as “evolution”), among others. The third and final category was Presentation, called like this because students were going to present their projects at the end of the course and saw this as an important stage of the evaluation process. The stage addressed features such as fluency, creative use of language, and translanguaging. When the document was done, we presented it to the students to confirm whether or not they agreed with the categories and asked their opinion about the elements to be considered and the distribution of points among the categories, which were different for each course (Table 1).

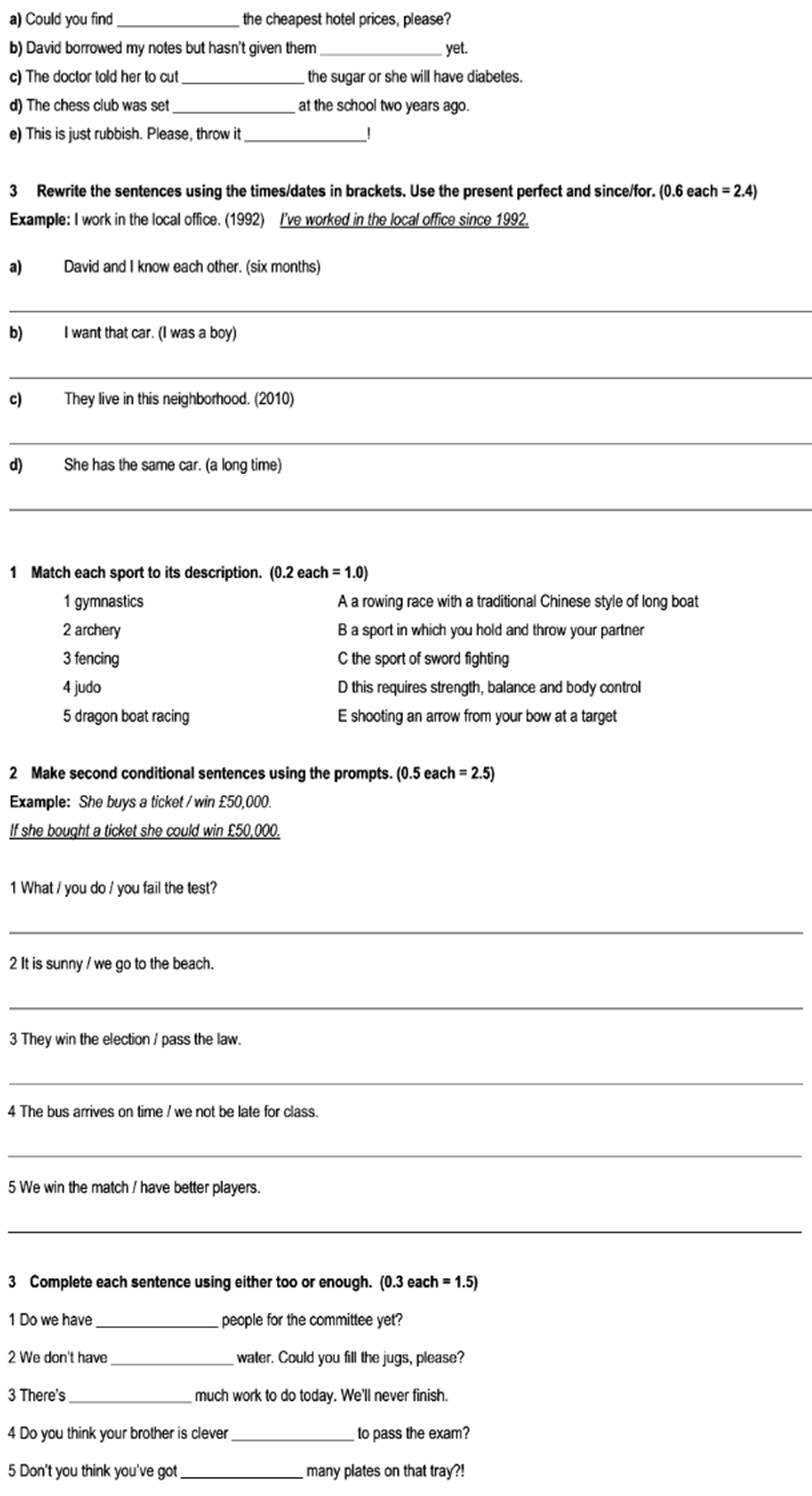

Table 1 Evaluation Criteria for the Projects

| Category | Elements Agreed upon with English 3 | Weight in Final Grade (%) | Elements Agreed upon with English 5 | Weight in Final Grade (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | (i) Participation; (ii) collaboration and group interaction; (iii) understanding the assignment | 30 % | (i) Use of language learned; (ii) effort and engagement; (iii) collaborative work | 40 % |

| Booklet | (i) Information design; (ii) scope of research; (iii) quality images; (iv) connection with the vocabulary of the textbook; (v) quotation of references | 50 % | (i) Creativity (getting the attention); (ii) inclusion of themes from textbook; (iii) adequate use of language | 35 % |

| Presentation | (i) Participation; (ii) listening and paying attention to others; (iii) fluency and translanguaging; (iv) presentation and reading | 20 % | (i) Communication (understanding and being understood); (ii) use of language learned; (iii) content; (iv) respect for time | 25 % |

It is important to highlight that the initiative of evaluating how they translanguaged through their repertoires came from the students themselves. During the classes, especially for students of the English 3 level, we tried to encourage them not to be afraid of mixing features from English and Portuguese in order to communicate. We saw this as a strategy to create a more welcoming and empowering classroom environment, allowing students to go beyond their strictly linguistic and English repertoire and, therefore, to say everything they wanted to say in a freer and more independent way. Moreover, our initiative with this was to break with monolingual ideologies as we disagreed with the belief that this mixing interferes with their English learning.

On this matter, when it was time for students to comment on what they saw as important features to be evaluated, some stated that we should look at “how well they mixed both languages”. We now think students’ suggested criteria must have resulted from their readings of our practices and discourses as teachers, as well as from their own expectations and backgrounds.

Final Steps

Despite this final evaluation and grading, we tried to maintain a formative and procedural assessment, providing ongoing feedback throughout the project. We gave students different types of feedback, such as comments on their writing/oral productions, on their collaborative work, and on their use of multiple modes. Besides, we attempted to promote spaces for peer feedback, where learners shared and interacted with each other and their projects. One of these moments was the final presentation, an encounter between all the groups from both levels in the final week of classes.

The idea for this encounter between English 3 and 5 was to have a space where students would have the opportunity to present their production to their peers. Moreover, we created a Padlet with a column for all 9 groups, where the audience had the task of providing comments on the work of their colleagues. We think this stage of the process dialogues with the Engaged Pedagogy proposed by Hooks (1994), as we saw students bringing their bodies and emotions to the classroom and experiencing things that were relevant for them. In addition, this was also an attempt to reduce the plasticity3 of assessment. Most of the time, students write texts that, after being sent, corrected, and graded by teachers, do not have any other purpose. With the encounter between the classes, students saw their peers make new meanings through reading and knowing their productions. One of them even commented that this was one of the best aspects of the entire process and a great opportunity for learning:

O melhor de participar neste tipo de trabalho é poder ver o que o colega está apresentando e com isso você aprende muito [The best part of participating in this type of assignment is to be able to see what the classmate is presenting and with this you learn a lot.]. (Student 11, English 3, Self-assessment form, 2021)

After the end of the semester, it was time for the final feedback. We went through all their answers to the self-evaluation forms and to the notes we took throughout the process. Based on the evaluation criteria agreed upon previously, we wrote detailed individual feedback for each student. This stage demanded a lot of time, so we must admit that this was only possible due to the privileged context in which we were working. If these reflections were to be taken to other localities and classrooms, where the number of students per class is greater, there is a strong possibility that this type of feedback had to go through an adaptation.

In dialogue with this aspect of the experience, we asked students what they would change about the evaluative project proposed. There were some students who expressed the desire to have both the production of the booklet and the formal test. One of the students even wanted to be evaluated on her listening comprehension of native speakers specifically, while another made some comments about how the incorrect use of verb forms made his “ear hurt” (Student 2, English 5, Self-assessment form, 2021).

As non-native speakers who are also constantly developing our repertoires, there are moments in which, as these students, we feel the need to be tested, to follow normative discourses, and of course, to be praised for our language skills. We do not mean to delegitimize our student’s desires, but we see these wishes as a reflection of the coloniality/modernity that constitutes our destitute bodies. As stated by Menezes de Souza and Duboc (2021), “coloniality cannot simply be ended; [...] hegemonic knowledges of coloniality cannot simply be erased or eliminated as they constitute our thinking as subjects constituted by and implicated in coloniality” (p. 905).

To conclude our analysis of the responses to the experience, we expected to hear about students’ emotions in relation to assessment. One of our main objectives was to provide a space for feelings that were different from the ones we frequently associate with evaluation, a sticky object (Benesch, 2012) in the classroom. On this topic, students commented:

sempre fico empolgada para aprender e principalmente quando tem atividades diferentes como a produção do booklet; [...] Eu amo trabalhos diferentes que sempre nos desafiam e onde podemos usar criatividade. Pra mim é muito importante e eu me sinto com voz em trabalhos assim, amo quando podemos ser sensatos/técnicos e ao mesmo tempo explorar o lúdico.

[I always get excited to learn, especially when there are different activities such as the production of the booklet; [...] I love different projects that always challenge us and where we can use creativity. For me, it is very important and I feel I have a voice in assignments such as this, I love it when we can be reasonable/technical and at the same time explore the ludic.] (Student 4, English 5, Self-assessment form, 2021)

Foi diferente e uma forma divertida de avaliação. Gostei bastante. Demanda um pouco mais de tempo que uma prova, mas é mais dinâmico. [It was a different and fun evaluation. I liked it a lot. It demands a little more time than a test, but it is much more dynamic.] (Student 11, English 3, Self-assessment form, 2021)

Here we witness feelings of motivation, closeness, excitement, love, and confidence. When Student 4, English 5, said that she felt she had a voice in this type of activity, we felt that we were able to perform an assessment that did not seek to exclude or control, but to empower and transform. Nevertheless, we did not expect that the emotions attached to traditional assessment practices would completely disappear. For instance, one student said:

I was so nervous during the presentation, so this messed up me, but I hope I could be understandable for the others (Student 8, English 5, Self-assessment form, 2021).

This student was not the only one who showed anxiety for the presentation. This suggests that the emotions linked to assessment will remain complex regardless of the evaluation mode and criteria. At the same time, teachers in different circumstances may follow our proposal and see what feelings arise. Thus, we trust that emotions are extremely diverse and neither do we have the power to nor should we aim at controlling how our students feel. Our goal with this project was to have an assessment that embraced this diversity and made room for feelings different from the ones often associated with tests and exams.

Avaliar se Avaliando

With the experience we presented in the previous section, we believe that we have accomplished our purpose of questioning traditional assessment conceptualizations and proposing an assessment otherwise for ELT. Conducting this project allowed us to put forward an evaluation method which understands that: (a) language cannot be measured by mechanical instruments, since it is not a system but a social and multimodal practice; (b) students’ linguistic repertoires are dynamic, diverse, and always in flux; and (c) knowledge is never definite but an ongoing construction. As stated in the title of the paper, our intention is to promote a learning that does not occur for assessment but one that happens with the processes conducted in the classroom.

We are, however, aware of the fact that some spaces will not provide teachers with opportunities to explore possibilities otherwise. Not all teaching contexts understand language as a social practice, nor do they have as their goal the promotion of transformative pedagogies. A proficiency test, for instance, may be the final goal at the end of the course. Thus, conducting traditional formal tests might be the only option available. It is our contention, nonetheless, that if we cannot change the evaluation instrument, we can strive to subvert the way we understand language, assessment, and its purposes. There may be no instrument that is the best, but if teachers want to transform their practices, these should be based on different perspectives of knowledge, correction, feedback, and learning.

Overall, we believe a goal in any ELT assessment practice should be what we call avaliar se avaliando. One of the fundamentals of critical literacy in Brazil is Menezes de Souza’s (2011) idea of ler se lendo or reading by reading yourself:

ler se lendo, ou seja, ficar consciente o tempo inteiro de como eu estou lendo, como eu estou construindo o significado (…) e não achar que leitura é um processo transparente, o que eu leio é aquilo que está escrito (….) Pensar sempre: por que entendi assim? Por que acho isso? De onde vieram as minhas ideias, as minhas interpretações?

[ler se lendo, in other words, being aware all the time of how I am reading, how I am constructing meaning (…) rather than thinking that reading is a transparent process, what I read is what is written (….) To keep thinking: why did I understand this way? Why do I think this? Where did my ideas, my interpretations come from?] (Menezes de Souza, 2011, p. 296).

We tried to rethink this idea from the perspective of teachers who are looking for ways to assess otherwise. We believe, regardless of the context, teachers ought to avaliar se avaliando, ou seja, ficar consciente o tempo inteiro de como eu estou avaliando, como eu estou construindo meus objetivos avaliativos (…) e não achar que a avaliação é um processo transparente, o que eu avalio é aquilo que é válido (….) Pensar sempre: por que avaliei assim? Por que esse feedback? De onde vieram os meus critérios, os meus instrumentos? [assess by assessing yourself means being aware all the time of how I am evaluating, how I am constructing my assessment goals (…) rather than thinking that evaluation is a transparent process, what I evaluate is what is valid… To keep thinking, why did I evaluate this way? Why this feedback? Where did my criteria or my instruments come from?]

As teachers, we recognize that we are implicated in these processes. When evaluating our students, we are deeply involved in the task, and the feedback and grades we grant are filled with our subjectivity, beliefs, and concepts of knowledge, language, and learning. It is our responsibility as educators to be aware of the genealogies and consequences of the choices we make, the actions we take, and the discourses we reproduce in our classrooms.

This exercise of reflexivity that we propose is also deeply connected to recognizing and embracing ours and the students’ emotions in the process. It is impossible, for instance, not to empathize with those learners who report feelings of insecurity and fear when they are about to take a test. In addition, it is an attempt to embrace our decolonial option and challenge the power structures in the classroom as we walked side by side with students in the creation of this project, allowing them to perform their agency and to collaborate with each other. Above all, this experience definitely changed our perspectives on learning, teaching and evaluation.