Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Antipoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología

Print version ISSN 1900-5407

Antipod. Rev. Antropol. Arqueol. no.18 Bogotá Jan./Apr. 2014

Austere kindness or mindless austerity: the effects of gift-giving to beggars in east London*

Johannes Lenhard

Ph.D., student at the Cambridge Social Anthropology department, University of Cambridge. BA in Economic from Zeppelin University, Germany, MSc in Economic Sociology from London School of Economics, MPhil in Social Anthropoly, Cambridge. jfl37@cam.ac.uk

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7440/antipoda18.2014.05

ABSTRACT:

The current austerity policies in the United Kingdom are creating a precarious situation for many people on the margins of society. Employing micro-level ethnographic analysis, this article addresses how government decisions affect people living on the street. Observations of how local policies demonize gift-giving to street people led me to revisit arguments about the positive and negative effects of gifts. Four months of fieldwork amongst people who beg in the City of London confirmed the Maussian ambiguity of gift exchange. The material benefit of monetary gifts is often accompanied by shared time and conversation; gifts to beggars can go beyond materiality and are hence able to create bonds of sociability.

KEY WORD:

Austerity, begging, gift-giving, money

Bondad austera o austeridad sin sentido: los efectos de entregar dones a los mendigos en el este de Londres

RESUMEN:

Las políticas actuales de austeridad en el Reino Unido han creado una situación precaria para muchas personas que se encuentran en los márgenes de la sociedad. Con un análisis etnográfico de nivel micro, este artículo aborda la manera en la que las decisiones gubernamentales afectan a las personas que viven en la calle. Observaciones sobre cómo las políticas locales satanizan el dar dones a la gente de la calle me llevaron a revisar los argumentos sobre los efectos positivos y negativos de estos dones. Cuatro meses de trabajo de campo entre mendigos en la ciudad de Londres confirmaron la ambigüedad maussiana de los intercambios de dones. El beneficio material de los dones monetarios a menudo está acompañado del tiempo compartido y conversaciones; los dones a los mendigos pueden ir más allá de la materialidad y, por lo tanto, tienen la capacidad de crear lazos de sociabilidad.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

Austeridad, mendicidad, el don, dinero.

Bondade austera ou austeridade sem sentido: os efeitos de entregar dádivas aos mendigos no leste de Londres

RESUMO

As políticas atuais de austeridade no Reino Unido vêm criando uma situação precária para muitas pessoas que se encontram às margens da sociedade. Com uma análise etnográfica de nível micro, este artigo aborda a maneira na qual as decisões governamentais afetam as pessoas que moram na rua. Observações sobre como as políticas locais satanizam o dar dádivas às pessoas da rua me levaram a revisar os argumentos sobre os efeitos positivos e negativos dessas dádivas. Quatro meses de trabalho de campo entre mendigos na cidade de Londres confirmaram a ambiguidade maussiana dos intercâmbios de dádivas. O benefício material das dádivas monetárias frequentemente está acompanhado por tempo compartilhado e conversas; as dádivas aos mendigos podem ir mais além da materialidade e, portanto, têm a capacidade de criar laços de sociabilidade.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

Austeridade, mendicidade, dádiva, dinheiro.

In Britain, austerity was chosen over stimulus as a result to the crisis of finance and the Euro. The UK issued the third largest regime of cuts in government spending in Europe. These savings do not only affect administration and defence, but also significantly impact the welfare state (Holloway, 2011; Reeves et al., 2013). In his 2013 Autumn statement, chancellor George üsborne explained that austerity was a necessary condition for all parts of society (Elliott et al. 2013). A 'leaner state' has come to be a universal and permanent goal for Prime Minister David Cameron. Following the Great Recession that started in 2008, these austerity policies have not been able to alleviate the macro-economic results of the crises, potentially even deepened them: more than 2.5 million people are currently unemployed, 60% more than in 2008. Almost 21% of people under 25 are without work (BBC, 2013). 3.8 million people receive unemployment benefits of some kind (BBC, 2013), again about 60% more than in 2008. Roughly 13.5 million (22% of the population) are 'income-weak' and the average level of household debt is high and growing (Knapp 2012). My concern, however, is where economics and statistics stop. How do the people dependent on the state cope?

I want to focus on those at the margins of the statistics, on people who are homeless and who beg on the street.1 Austerity policies have begun to push citizens who were able to claim housing benefits or disability living allowance into homelessness. According to recent estimates, more than 20% of former claimants will not be able to receive benefits anymore after the introduction of the 'personal independence payment'; a similar effect could result from the decentralisation of the welfare decision under the Localism Act (2011), and stricter examinations regarding eligibility (Fitzpatrick et al., 2012; MHE, 2013:5; Reeves et al., 2013:3; Wilson, 2013). The number of homeless people in London has increased by 100% since 2008 (Fitzpatrick et al., 2012:64). This process has just started; the effects can take several years to 'trickle down' through the system (Cooper 2011).

In this context we have seen the relaunch of a 2003 Lambeth Council campaign against giving to people that beg in London. The silhouette of a person is marked with coins on a pavement. The headline reads: "Are you killing with kindness?". Lambeth Council is attempting to warn about the potential usage of the monetary gifts homeless people receive for drugs that might eventually kill the recipient. Since 2010, the image has been used by at least ten authorities across London, Newcastle and Oxford. Most recently, a similar campaign has been seen in the City of London and Tower Hamlets. Is the issue of giving to people on the street dismissible in this way?

During my fieldwork over the last two years, I have encountered meaning attached to gifts to people who beg on the street that goes far beyond the material benefits of money. Statements from people like Kevin2, who had begged for almost one year near London Wall when I first met him in 2012, paint a more complex picture:

- 'Many people think, that if they give, that keeps me on the street - but it really makes life bearable [...] What I appreciate is respect. Respect and understanding make me feel like a human being and connect me to people.'

Without help from strangers, Kevin suggests his life is 'unbearable'. It is however not simply the material necessity of money that makes his life liveable. The underestimated social aspect of giving, the interaction, makes him 'feel human'. Gifts that can form relationships between him and his giver bridging inherent distances, both literally in space but also in mind. This connection has significance by reminding Kevin of his often forgotten dignity.

I frame giving to people who beg within the anthropological discourse on gifts, oscillating between scholars who depict gift-giving as self-interested, rational action that reproduces inequality (Becker 1973; Emerson 1976; Bourdieu 1977; Sahlins 2004), and those who see it as an altruistic gesture that forms the basis of sociality (Cheal 1987, 1988; Godbout and Caille 2000). With special emphasis on its ambiguous social effects, I argue - in accordance with Mauss' original thesis (Hart 2007; Mauss 2001) - that gifts to people on the street can be both. They can be a rational, usually monetary gifts in the giver's own moral interest that merely reproduce the gap between the person sitting on the ground and the stranger walking past. But they can also be donations that represent a sense of understanding and connecting trust. This latter form is the 'positive' side of gifts, which is often denied in contemporary public discourse such as the revived Lambeth campaign mentioned above. I do not want to romanticise gifts or brush aside their negative aspects in the street context (Hall 2005; Williams 1993), but it is important to recognise the potentially positive effects in a city suffering from the effects of austerity.

Gifts to people who beg

Although homelessness and poverty have long been topics in sociology and anthropology (Taithe 1996; Burrows et al. 1997; Kennett and Marsh 1999; Ravenhill 2008; Fitzpatrick et al. 2009), begging has only been analysed marginally. Furthermore, existing accounts focus on the reasons for begging (Fitzpatrick and Kennedy 2000), policy failures (Dean 1999), or ethnographic observations of homelessness (Murdoch 1994; Merz et al. 2006). Most of these contextualise social exclusion and depict the street person as an outsider (Jordan 1996; Dean and Melrose 1999). Only very recently have scholars become interested in analysing begging within the framework of the gift (McIntosh and Erskine 1999; Hall 2005). In contrast to my own account, McIntosh and Erskine (1999) focus on the giver, whereas Hall (2005), even though interested in people who themselves beg, does not consider positive aspects. I argue that gifts to people who beg bear a potential for interactional and inclusive relationships.

In anthropology, theories of the gift tend to follow opposite lines of reasoning (Gudeman 2001). One strand contends that gifts are acts of "pure generosity" and, as such, "perfect gifts" (Carrier 1994; Belk 1996; Donati 2003). The exchangists, on the other hand, put forward the argument that no gift can be purely altruistic; self-interest is always involved at some level, possibly unconsciously. They define the gift in general as an expression of calculating behaviour, linked to the expectation of return (Gouldner 1960; Becker 1973; Emerson 1976; Bourdieu 1977). Mauss' original vision was more holistic. He stressed the combination of "something other than utility" that is "in no way disinterested" and proposes a research strategy that strives for the "whole" and the "concrete" (Mauss 2001:92,95,100,103,106). Mauss' gift is both interested and altruistic, and can in turn result in hierarchy or inclusion. This ambiguity should also be the point of departure with regards to the effects of almsgiving.

Giving to people who beg has a potential to go in both directions. It turns into a self-interested act perpetuating inequality if we follow the exchangists. The giver donates in order to satisfy his own conscience, acts primarily rationally and motivated by profit as Emerson (1976) and Davis (1992) have argued, and maintains distance. The desired 'profit' can be conceptualised as 'mental satisfaction', in response to the gratification of 'having helped somebody. People give in order to receive ('do ut des, Komter 1996:3), even if this return is merely moral. This argument is developed explicitly by Bourdieu. He observed that for the Algerian Kabyle, the gift is "an attempt to accumulate symbolic capital and gain an advantage over the other party" (Bourdieu 1977:178). He goes on to assert that the principle of power-maximisation and the goal of domination are overarching. As he puts it, gift-giving "[...] becomes a simple rational investment strategy directed toward the accumulation of social capital" (ibid.:236). Schwartz (1996) follows this argument, including a psychological perspective. According to him, gifts can be hostile and offensive by "imposing a different person on you", namely the identity of the giver (ibid.:70). In the case of begging people, the giver might unconsciously create a situation of dependence and hierarchy, enforcing a particular system of monetary exchange.

On the other hand, the "economic absorption of the gift" (Callari 2002:251; Davis 1992:21) has been harshly criticised by many anthropologists. Godbout (Godbout and Caille 2000:97) proposes an alternative to Bourdieu. For him, the gift is without calculation. It spontaneously grows out of an impulse to give and is "incompatible with a means-end-relationship" (ibid.:97). In this school of thought, giving to beggars appears as an altruistic activity that is able to bridge rather than amplify distance. Gifts can be the basic principles of sociability, "creating and enforcing social solidarities". In his study of the Canadian Winnipeg, Cheal (1988) describes how the gift creates a moral economy and social ties. For begging people, those ties can be formed through affection, empathy, or simple respect and understanding. In this way "giving is the institution that creates social cohesion" and positively links people (Donati 2003:246). Even though giving can be gratuitous, and no material return is obligatory, a relationship of feeling and emotion might develop.

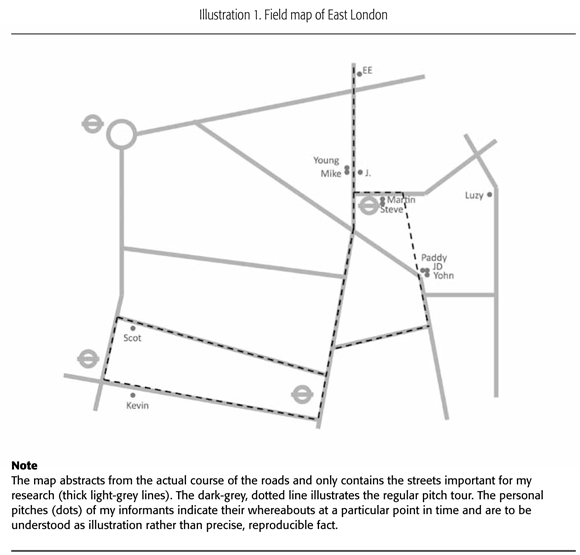

In this article, I argue that a rigid dualism does not take us far. My case of street people in East London (see Illustration 1 below for an overview of the field site), picks up Mauss' holistic conceptualisation of the gift that is both interested and altruistic, at times hierarchical or inclusive, but most importantly potentially interactional (reciprocal) and social (Carrier 1991:122) rather than exclusively one-sided (Hart 2007). I measure the ambiguous results of almsgiving between hierarchy and distance, on the one hand, and bonds of cohesion and positive emotions on the other.

An ethnographic approach

During my time in the field in 2012, I undertook participant observation in the triangle between Liverpool Street Station, Brick Lane and Old Street in the East of London. Although street people in general and people who beg in particular are found throughout London, the City is of specific interest. It comprises a distinctive mix of commercial banks attracting a diversity of potential givers and sophisticated infrastructure for homeless people (shelters, day centres etc.) (Murdoch 1994).

My daily 'fieldwork excursion' (Lankenau 1999) evolved into a tour from Liverpool Street station via Commercial Street to the surroundings of the station, where I met with most of my roughly fifteen informants on a regular basis. The usual position of each of the people I spoke to can be found in Figure 1 below. I endeavoured to take in a range of mornings, afternoons and evenings during weekdays and weekend; each excursion lasted for two to five hours. I conducted semi-structured interviews with most of them, and observed behaviour, gestures, and actions sitting with them in parks, on the pavement, in alleyways, and in their hideouts.

I approached my informants on the basis that they were begging rather than busking or selling goods and services. Narrowly defined as the act of soliciting a voluntary gift in a public place (Melrose 1999; Dean 1999), begging was the defining activity. Some of the participants were selling homeless magazines or lighters at other times, but all of them were begging regularly.

A final methodological issue evolved around the gifts flowing from the researcher to the informant. I often felt uncomfortable stealing my informants' 'working time'. Following Williams (1993), I decided on compensating them for formal interviews as a "way of expressing gratitude and respect". I bought food, took them to a fish and chip shop, or bought medical equipment they needed. Money very rarely changed hands. At other times, I felt unable to answer, as Geertz (2001:30) puts it, the "blunt demands for material help and personal services". Reciprocity was on the one hand vital to establish and sustain relationships with my informants, particularly in the early phase of the research, but on the other it was voluntarily given time that was an expression of necessary trust. This latter trust was desired from the point of view of obtaining valuable information but it also had to be balanced with an analytic eye. "It is this [combined] attitude, not moral blankness, which we call detachment or disinterestedness" (Geertz, 2001:40) - and which serves as the basis of anthropological research. The findings I will present originate from these 'disinterested' encounters with people on East London's streets.

Give, receive, reciprocate - Effects of almsgiving

As the anthropological discussion indicates, the gift's potential social results are ambiguous. The empirical material I gathered in East London bears witness to this ambiguity, particularly with regard to the material gift of money. Money is often linked to negative outcomes, thought to reproduce the hierarchical distance between giver and donor. But the gift of money is also able to imply understanding that initiates bonds of emotion and respect. In this social tie lies the focus of my analysis. For people who beg, sociality often is associated with the figure of the regular as opposed to the one-off giver. Whereas the former visits frequently, talks to the street person and engages in interaction, random gifts are often linked to short-termism that lacks connection. As I argue, many singular monetary donations tend to result in contingent social effects and potentially reproduce exclusion and inferiority. But any 'giver' already exhibits an understanding and appreciation of the beggar and his situation worth analysing further.

Giver and non-giver

Givers, gifts and their effects are not alike. Money is the most frequent gift, but food is also common. This diversity also influences the gift's potential social effects. In simple terms, we tend to believe that money reproduces hierarchy, and is at best able to facilitate interaction, while the possibility of personal, mutual ties is frequently dismissed. Let me zoom in on this nexus first of all with a focus on the giver.

I spoke to roughly 100 randomly selected people on the streets of East London about their giving habits. The majority of these informants were not clear about why they actually give to people who beg. Reasons for giving varied widely from compassion, their own mood, and the interest to establish a personal bond. They commonly gave simply because 'they felt in a good mood. Others simultaneously doubted the effectiveness of their gift but were indifferent about potential effects. Altogether, the decision always "involves an interweaving of economic, social and moral considerations" (McIntosh and Erskine 2000:10). Titmus highlights this point:

- "Manifestations of altruism in this sense may of course be thought of as self-love. But they may also be thought of as giving life, or prolonging life or enriching life for anonymous others." (1973:240)

The people who beg take this notion one step further. Whereas Scot describes the giver's ambiguous motivation, Martin clearly differentiates the giver from the non-giver:

- Scot: They could just not give and walk pass. People that give already got a heart and don't want to be in the same situation.

Martin: Maybe some want a good conscience, it makes them feel better. But this is not the whole feeling - it makes them feel good, they are getting some account by doing me a favour. I'm glad they feel good as well.

For both Scot and Martin, some givers do give out of self-interest. They exchange a gift for a positive emotion that can be signalled by the person who begs and smiles, thanks the giver or bows his or her head. As soon as people give, interaction takes place. This interaction is important both for the giver - invoking satisfaction and a desired good conscience - as well as for the begging person. The giving as such immediately exposes understanding on the part of the giver that the non-giver lacks. In contrast to the findings of Hall (2005:9: "We wanted no contact, no interest paid beyond that required to prompt a fleeting cash donation"), I found that people on the street in East London were interested in the sociality that potentially accompanies the monetary gift. It is the complexity of this gift I want to open up in the following section.

Gifts of money

Pocket change is an easy gift, always available with negligible opportunity costs. People carry cash around all the time - and often don't have any usage for pennies. However, money is not only the most common gift, but also the most contestable. It is worth looking at this ambiguity in detail. I want to follow up from the claim of the 'Killing-With-Kindness' campaign but illuminate both sides from the perspective of the people who are actually doing the begging: What kind of effects do (material) gifts have for street people themselves? What do street people feel in a situation of gift exchange?

First of all, money is a material necessity for many street people. Kevin put it in the following way: 'If society found itself that you need money in order to have food, than I need it.' Mike even more drastically claims that 'money is life', and that nothing can be done without it. Even though Mike sits in front of a coffee shop, he is excluded from his direct environment. He does not have the necessary means - money - to buy into the culture around him. Godelier (1998:2) takes this to an abstract level: "While in other parts of the world you must belong to a group in order to live [...], in our society [...] everyone must have money." One might contest that food can do the same job. Two objections, however, immediately arise. First, from the side of the givers, money is an easy gift. Change is easily available and implies a small sacrifice in contrast to food that can generate direct pleasure (Sahlins 2004: 215f). Additionally, food does not allow for choice. Several of my informants expressed this explicit need to make a choice according to one's own preferences. A gift of food is less liberating and provides less potential for self-realisation. As J., who himself lives in a council house in Hackney and sketches his dog or surrounding houses while begging, explains: 'If I cant even chose my own food, what else? I don't have no money anyway.' Zelizer (1997:149; Lee 2002:93) similarly describes choice as the potential upside of monetary gifts:

- "Only money could liberate the charity customer by turning her or him into an ordinary consumer [...] money granted the power of choice, transforming the purchase of the most ordinary commodities into self-enhancing exchanges."

Even more importantly, money does not stigmatise (ibid.:149). On the contrary, it symbolises trust. 'I'd rather have the person giving me the trust', I heard Kevin say. So money has positive sides as an easy gift for the giver and as trust-bearing and liberating for the street person. But for many critical commentators its downsides are overwhelming.

Zelizer (1997) turns the issue of trust upside down. The "danger of cash" emerges if it is given to people with "sufficient moral" and "practical competence" (ibid: 158f): "In the hands of the morally incompetent poor [...] money could turn into a dangerous form of relief [...] liquor money" (ibid.: 120/131). With the above argument, Zelizer seems to conceal stereotypes behind sophisticated language. But even many of my informants - Martin and Steve explicitly - admitted to be suffering from alcohol or drug addiction. For Steve, alcohol plays a crucial role. He begs to primarily feed his dog, and secondarily his liver. To avoid such difficulties, money as a gift is often "earmarked" (Zelizer 1997). As Offer (1997:454) explains, "when money is given, its transfer is circumscribed by strict rules" This is also true for the street context. I observed an incidence sitting next to J. and his dog, when a young woman approached him. J. was drawing the skyline in front of him while the woman kneeled next to him and handed him a bag full of dog food: "I know you prefer money, but I thought it would be better to buy dog food. I mean, I know you are ehm, on drugs. Next time." Even though this kind of 'literal' earmarking works, as soon as money is involved, the power of the giver is drastically limited. How can they control how their donation is put to use?

The potentially most severe problem with regards to the social effects of the gift, however, might be money's anonymity. In interviews, Kevin expressed this explicitly. For him, 'money can never let him be seen in a different light.' He misses the conversation, being recognised as a person, and not as an almsbox. Money for many street people is often not the gift that has the potential to create a relation; it is limited to anonymously curing the problem of subsistence or supporting addiction. As Simmel (2004; Osteen 2002) puts it in his 'Philosophy' in a daring comparison to prostitution, monetary relationships tend to be fleeting. Money "does not imply any commitment" and is as such the "appropriate equivalent to the fleet-ingly intensified [...] sexual appetite that is served by prostitution" (Sim-mel 2004:376). Appropriate for a short-lived encounter, a monetary gift can cause distance rather than create relationships (Simmel 1908).

JD slightly twisted this negativity. She explicitly introduced the idea of money as a mediator. For her, 'money is a facilitator. But people have to engage with you in order to get you emotionally.' As described above, most gifts, and so also mostfirst gifts, are money. Hence, whatever might develop between a beggar and his giver is often based on such a first monetary gift. In this way, money might serve as what Hart and Hann (2011) call a "facilitator" bridging the gap between materiality and social significance. Money can function as Simmel's (1950:392) "first gift" expressing a "devotion', while constituting a probe of the relationship. This probe facilitates a link (Gudeman 2001:460). Money does potentially enable relationships - even though it is often insufficient. An emotional connection is mostly only possible through a non-monetary exchange that can, however, be prepared by (and eventually accompany) money.

Money is itself not necessarily the connecting object. In contrast, its acceptance can lead to a deepening of the hierarchical relation between donor and recipient. 'Ordinary people might just drop a quid', is how Scot describes the act of giving. They not even look down 'just as on a parasite' (Kevin), won't say a word or accept the thank you, and even throw the money at the beggar. I observed many incidences - particularly in the evening and night hours - when money was dropped by drunken passers-by who were accompanied by a girlfriend or a group of boys. The giver in this scenario often wants to impress. Having been approached by Steve, a passers-by turns away from his friends who observe him carefully: "Eehm - look - I am a good boy. Have a pound and get drunk, but leave me alone." Simmel (1908:155) reflects on this in the following way:

- "The goal of assistance is precisely to mitigate certain extreme manifestations of social differentiations, so that the social structure may continue to be based on this differentiation."

The status-quo of hierarchical exclusion can as such be reinforced by a gift that is tossed at the beggar or given to impress the evening's date as Scot described to me as well. This is what Zelizer (1997:96) recognises in the tip demonstrating the "inferiority of the recipient". Crucially, others claim that it is the lack of (material) reciprocity that amplifies difference and inferiority (Herzfeld 1987; Gudeman 2001; Mauss 2001:95). A lack of reciprocity defines an inferior gift that is not able to connect. I argue that even in the case of begging, reciprocity is often apparent. Reciprocity takes place through interaction.

Even if one does not follow Godbout (Godbout and Caille 2000) in his belief in the ties through unilateral gift or disregards Titmus (1973) societal contract, one can hardly dismiss the existence of a return in many begging encounters. Different possibilities for counter-gifts appear. Some beggars offer material returns whereas others give back immaterially. Yohn offers cigarettes for instance, whereas I saw Paddy giving away his artworks -often not as an immediate, but rather delayed return gift; not in order to forge exchange, but in a gift-like fashion (Bourdieu, 1977). In Paddy's case, these artworks are painted with his own blood and as such directly 'bear a mark from the giver'. Paddy deems a donation - often as part of an ongoing interaction between regular and himself as I will describe below - valuable enough to be reciprocated with a work that originates in his own very personal creativity and suffering. Reciprocity in the form of one's own suffering and bodily markers goes beyond mere material-commercial return. A second group of 'material returners' camouflage the almsgiving as market exchange. They try to sell small wire-sculptures (as Daran), drawings (J.) or shoe-polishes (Kevin) - in a similar way to people selling homeless-magazines (e.g. the 'Big Issue').3 The receivers themselves seem to have an urge to give something back - or even to offer something in advance. They fashion giving as interactional exchange.

Additionally, street people often return immaterially. They say 'Thank you, 'God bless' or 'Good man, as Paddy and Pagan, or distribute hugs as in the case of JD and Luzy. Jokes, bows or a dance from his dog are common counter-gifts for Steve. He wants to at least entertain his givers. Those immaterial replies are more than what Offer (1997:454) calls "normal pleasantries". They often go beyond mere conventions, have a moral or religious connotation or drift into the realm of intimacy. Steve recognises that he does indeed not give back material goods, but emotions (see also Simmel 1908:158f): 'No, gifts are not free. They are giving me and I'm not giving them nothing moneywise. But they are getting my happiness. They see me shining.'

For Yohn, 'money is important by any means, but talk and time are connecting in a deeper way'. So, money has often less of a social and primarily a material function. Money's anonymity potentially reproducing hierarchy cannot be completely argued away. However, any gift - also that of money - is a sign of respect. Hence, money can be a liberating and trust-bearing facilitator for a relationship. If such a relationship develops, it is very often based on reciprocity, on ongoing social interaction. This interaction often goes beyond money and its materiality. Words and time are often accompanying the gift.

Gifts beyond money

Time and talk imply respect and understanding that are refused to street people by the majority of passers-by. Steve even claims that this devotion is 'worth more' than the material necessity: it is able to remind the person of his or her dignity. Godbout (Godbout and Caille 2000:78) stresses the positive influence of listening and giving of time:

- "People from every social milieu participate in the modern gift, not only by donating money, but also by giving of their time: listening to people, making visits, accompanying the aged, and so on."

As Pagan claims, connection can only happen 'if you have a conversation.' Words and respect potentially connect beggar and giver and they include the two in a dyadic relationship. I observed Steve being visited by a young woman on evening in June. She sat down next to him immediately and seemed to deliberately have brought two cans of beer. The two were talking for 15 minutes in front of Steve's temporary spot at the station. Steve told me afterwards: "Ohyeah, she kinda comes every day and sometimes she sits down. I know her name and stuff and I know what she works" The mere fact that both engage in a conversation, even in regular conversations, marks a connection. From the side of the giver it signifies empathy and interest.

Sometimes, beggars are not willing to accept such interest (Hall, 2005:9), but in the case of my research it was very much desired. To return to the classic text of Mauss, the time somebody takes off to sit down and talk clearly "bears a mark from the giver", is a part of the giver that is transmitted with the gift (Mauss 2001:15f). The words and the implicit meaning of them establish a positive and approximating connection. Steve and Kevin both claimed that such gifts make them feel like 'a human being' (see Godbout and Caille 2000:145).

Even though the above argument proposes a counter-narrative - people who beg do not only profit from money materially but beyond that in a social sense - this side of the coin does not exclude the more common reading. The general exclusion of beggars from consumer culture is not deniable and the sources that make this their main argument are not to be contested (Dean 1999). I argue, however, that the gift is an important means of creating moments of self-esteem and respect in dyadic relationships. Even though, the difference is hardly recognisable from the viewpoint of the giver, for people who beg like Kevin, this is a crucial improvement from the existence 'as a parasite'.

One-off and regular

Paddy was the first who pointed out the difference between 'one-offs' and 'regulars'. For him, who mostly stands silently in front of the Tesco on Commercial Street, regulars possess knowledge that is crucial for his income. His regulars know that he is begging next to Tesco five days a week for between two and three hours starting at 5pm each day. But beyond his material dependence on this knowledge (Merz et al. 2006:4,21,38), it is the social effect of relationships to regulars that differentiates them from one-offs.

One-offs might also interact with the people they give to. They demonstrate interest. These incidences of interaction are often nevertheless still fleeting. The fleetingness already becomes apparent in the way in which one-offs give: many of them drop the coin while walking, don't look into the beggars eyes and keep on talking to their company. Godbout (Godbout and Caille 2000:185) describes this as follows:

- "We experience a vague uneasiness, a certain shame, stemming from the fact that, in the very act of giving, we confirm in our eyes [...] his/her exclusion from society, for this act cannot establish a social tie. We evade the eyes of a beggar and we rapidly move away after having given, thus refusing signs of gratitude."

One-off sometimes exchanges a couple of words with the person on the street, but the exchange normally doesn't exceed 'Here you go' and 'Have a nice day'. As Yohn expresses it 'they are closing the glass door looking through the glass window back at you too frightened to talk to you.' The one-offs might be the ones that Martin, Y. or Steve describe as 'pleasing their good conscience'. However, the exclusion can be compensated by higher sums of money which several of the street people pointed out to me. Regulars are on average giving less. In some situations, begging people (see Hall 2005:9) dominantly disregard the additional social benefits of begging in favour of a sole focus on support for subsistence. It is a second context, in which street people develop relationships to what they call 'regulars'.

As already alluded to above, Paddy has many regulars. Usually, he casually stands in front of Tesco and people know that he is looking for (material) help. One lady that I frequently observed talking to him visits two to three times a week. They exchange words, know each other's names and she regularly buys meals from Nando's for him. She even knows his preferences when it comes to Nando's meals. Paddy greets her before she disappears in the Nando's and smiles at me: "That's my girl. Every week, she buys me a meal. I've known her for a year or so now." It is this interaction far beyond a mere 'Take this' and 'Thank you' that constitutes the core difference between regulars and one-offs - and enables the gift accompanied by the surrounding sociality to have inclusive effects.

Regulars usually see 'their beggar' from a couple of times a day to once a month. It is on these occasions, that a relationship can slowly develop. As described above with Steve and his female regular, they take out a minute, sit down and talk - 'they go the extra mile' as Scot explains. Steve explains that from those conversations, both giver and recipient 'learn about each other's life' and exchange personal information. This does not mean, however, that regulars are not of material importance for the people who beg. We already heard from Paddy how he is dependent on his regulars' contributions. Others were similarly materially connected to particular regulars. Steve got a Kindle from one of his regulars and frequently receives books from others. He loves reading - but would himself not spend money on books. His regulars know about his passion and this is how the chain of presents developed again based on a connection between material components and knowledge. According to Scot the regular makes 'conscious decisions', possibly even plans ahead in the morning ('I need a pound that I can give to Scot'). Through this, they are part of what Lee (2002:86; Godbout and Caille 2000:174f) calls an "empathetic dialogue". This literal and metapho-ric dialogue can potentially support the formation of an inclusive mutual relationship. Although also this connection is still potentially unstable -moving to another pitch or part of town is not uncommon - it is often a projectable constant.

In these relationships to regulars, reciprocity is most likely. Steve's bloodworks for instance were exchanged in the context of regular-relations. One day, he suggested to one of his regulars that 'next time you come, I bring one of the 'blood-works' I scribble when I cant sleep'. He wanted to 'give' something back to his regular, interact also on the material level. I witnessed incidences where other informants offered cigarettes or drawings that were not immediately connected to specific gifts from the donor. Hence, the notions of interaction, return and reciprocity find their peak in long-standing relations with regulars. It is not only the material component of the gift - of money, of wishes, of food - that establishes this return. Stretching the idea, already the conversational interaction (exchanging personal knowledge for instance) goes beyond mere convention. The development of a connection is not necessarily linked to visible reciprocity, but on emotions, on empathy and gratitude. To return to the theoretical basis of the argument, this findings bears witness to the ambiguity of the gift: a close reading of Mauss (2001:50ff) suggests that the relationship between giver and receiver is dependent on the tripos of 'give-receive-reci-procate'. Paraphrasing Graeber (2001:111,225; 2011), one might say that the repetitive act of 'giving without returning' might further deepen the hierarchical nature of the relationship. The giver acknowledges the needi-ness of the street person and acts on this - but does the lack of exchange might make it impossible for the relationship to be balanced? On the other side, gifts do not always seem to be dependent on the reciprocity to have a social effect. As Scot describes some of his regulars: 'They don't care, sit down in their suits and cuddle me if I had a bad day.' He might exaggerate in this statement, but it reflects part of the finding of this paper: gifts to people who beg can have positive social effects. In times of recession and austerity, gifts are not only of material importance for street people, they might also make them feel human.

Austere kindness or mindless austerity

Recession and austerity create a situation of increased precariousness for people on the street. Not only does the government save money by renaming welfare benefits while increasing their conditionality, many local authorities also continue their campaigns against private giving to street people. Money is often a material necessity for the people that are cut off - or have decided to cut themselves off - from state strings. My fieldwork in East London led me to revisit arguments about the nature of different gifts.

As I argue in this paper, giving to people who beg is not necessarily a one-sided action concentrated on the material aspect of money. Rather, its significance in the social realm can be found in its interactional aspect and its potential to create a connection. Especially when performed by regulars - people that donate frequently to a particular recipient - giving develops a component that links the two parties. A dyadic relationship can grow, which signifies respect and understanding for the person who begs. A gift implies respect and understanding - even if linked to an at first potentially 'invisible countergift'. I see a vast field for future research in this direction -that might also more explicitly focus on the politicality of the topic and its historical development than my own paper.

I would like to end with a last observation of apparently methodological significance unfolding far beyond the methods. In my own work as a researcher with homeless people, I found resonances to the above notion of ambiguous giving. Some of what one might call my informants were explicitly appreciating the act of talking to me for reasons of sociality rather than 'communicating facts'. As Desjarlais (1997:195) describes: "most residents valued conversations for the companionship they provided and for the ways in which they enabled one to make contact with others". But what about the negative side of my own research, of my intrusion? What about the material demands my presence spurred? It is undeniable that giving can have negative effects - increasing dependency or hierarchy. But as my findings suggest, both a researcher and a stranger on the street might not necessarily follow the government in its mindless austerity, at least when it comes to 'immaterial gifts' of time, talk and respect. Many homeless people value austere kindness beyond materiality.

Comentarios

* This paper is based on ongoing research, which started in 2011 as part of a masters degree at the London school of economics. It was partly funded by a grant from the Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung für die Freiheit. I want to thank Sandy Ross and Raffaella Taylor-Seymour for comments on drafts of this paper as well as the people on the streets I got to know so well during my research.

1 As I explain in the methodological section below, my informants are characterised through their engagement in begging. I try to avoid referring to them as 'beggars', however, and instead use 'people who beg', 'street people' or 'begging people' interchangeably.

2 All names in this paper are anonymised and coded by the researcher to protect the security of the participants.

3 The difference to 'buskers' or Big-Issue sellers, however, is the primary focus on begging rather than 'selling'. The exchange is either delayed reciprocated in a gift-like fashion (Bourdieu, 1977) or only is an add-on to the begging (a second order 'profession' so to speak).

References

1. BBC. 2013. Economy Tracker: Unemployment, accessible: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10604117, aufgerufen: 17/11/2013. [ Links ]

2. Becker, Howard P. 1973. Man in Reciprocity: Introductory Lectures on Culture, Society and Personality, Wesport, Con: Greenwood Pub Group. [ Links ]

3. Belk, Russell W. 1996. The perfect gift. In Gift-Giving: A Research Anthology, eds. C. Otnes and R. F. Beltramini, pp. 59-84. Bowling Green, OH, Bowling Green State University Populat Press. [ Links ]

4. Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

5. Burrows, Roger, Pleace, Nicholas and Quilgars, Deborah. 1997. Homelessness and Social Policy. London, Routledge. [ Links ]

6. Callari, Antonio. 2002. The Ghost of the Gift - The Unlikelihood of Economics. In The Question of the Gift - Essays across disciplines, ed. M. Osteen, pp. 248-265. London, Routledge, [ Links ].

7. Carrier, James. 1994. Gifts and Commodities: Exchange and Western Capitalism Since 1700. London, Routledge. [ Links ]

8. Carrier, James. 1991. Gifts, Commodities, and Social Relations: A Maussian View of Exchange. Sociological Forum, 6(1), pp.119-136. [ Links ]

9. Cheal, David J. 1987. Showing them you love them: gift giving and the dialectic of intimacy. The Sociological Review, 35, pp.150-169. [ Links ]

10. Cheal, David J. 1988. The Gift Economy. London, Routledge. Cooper, Brian. 2011. Economic recession and mental health: an overview. Neuropsychiatrie: Klinik, Diagnostik, Therapie und Rehabilitation: Organ der Gesellschaft Österreichischer Nervenärzte und Psychiater, 25(3), pp. 113-117. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21968374. [ Links ]

11. Davis, John. 1992. Exchange. Minnesota, University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

12. Dean, Hartley. 1999. Begging Questions: Street-Level Economic Activity and Social Policy Failure. Bristol, Policy Press. [ Links ]

13. Dean, Hartley and Melrose, Margaret. 1999. Easy pickings or hard profession? Begging as an economic activity. In Begging Questions - Street-level economic activity and social policy failure. ed. D. Hartley, pp. 83- 101. Bristol, Policy Press. [ Links ]

14. Donati, Pierpaolo. 2003. Giving and Social Relations: The Culture of Free Giving and its Differentiation Today. International Review of Sociology 13(2), pp. 243-272. [ Links ]

15. Elliott, Larry, Wintour, Patrick and Sparrow, Andrew. 2013. Autumn statement: George Osborne refuses to ease austerity. Guardian. [ Links ]

16. Emerson, Richard. M. 1976. Social Exchange Theory. Annual Review of Sociology2, pp. 335-362. [ Links ]

17. Fitzpatrick, Suzanne et al. 2012. The homelessness monitor England 2012. [ Links ]

18. Fitzpatrick, Suzanne and Kennedy, Catherine. 2000. Getting by: The Links Between Begging and Rough Sleeping in Glasgow and Edinburgh. Bristol, Policy Press. [ Links ]

19. Fitzpatrick, Suzanne. Quilgars, Deborah and Please, Nicholas. 2009. Homelessness in the UK: Problems and Solutions. Coventry, Chartered Institute of Housing. [ Links ]

20. Gasche, Rodolphe. 1997. Heleocentric exchange. In The Logic of the Gift: Toward an Ethic of Generosity, ed. Alan D. Schrift, pp. 100-117. New York, Routledge. [ Links ]

21. Geertz, Clifford. 2001. Thinking as a Moral Act: Ethical Dimensions of Anthropological Fieldwork in the New States. In Available Light: Anthropological Reflections on Philosophical Topics, pp. 21-41. N.J., Princeton University Press, [ Links ]

22. Godbout, Jacques and Caille, Alain. 2000. The World of the Gift. London, McGill-Queen's University Press. [ Links ]

23. Godelier, Maurice. 1998. The Enigma of the Gift. Cambridge, Polity Press. [ Links ]

24. Gouldner, Alvin W., 1960. The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), pp.161-178. [ Links ]

25. Graeber, David. 2001. Towards an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York, Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

26. Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. New York, Melville House Publishing. [ Links ]

27. Gudeman, Stephen. 2001. Postmodern Gifts. In Postmodernism, Economics and Knowledge, eds. Stephen Cullenberg, Jack Amariglia and David F. Ruccio, pp. 459-474. New York, Routledge, [ Links ]

28. Hall, Thomas. 2003. Better Times Than This: Youth Homelessness in Britain, London, Pluto Press. [ Links ]

29. Hall, Thomas. 2005. Not Miser Not Monk: Begging, Benefits and the Free Gift. Sociological Research Online 10(4), pp.1-13. Available at http://www.socresonline.org.uk/10/4/hall.html. [ Links ]

30. Hart, Keith. 2007. Marcel Mauss: In Pursuit of the Whole. A Review Essay. Comparative Studies in Society and History 49(2), pp.1-13. [ Links ]

31. Hart, Keith and Hann, Chris. 2011. Economic Anthropology. Cambridge, Polity. [ Links ]

32. Herzfeld, Michael. 1987. Anthropology through the Looking-Glass: Critical Ethnography in the Margins of Europe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

33. Holloway, Frank. 2011. Gentlemen, we have no money therefore we must think - mental health services in hard times. The Psychiatrist 35(3), pp.81-83. [ Links ]

34. Jordan, Bill. 1996. A Theory of Poverty and Social Exclusion. Cambridge, Polity Press. [ Links ]

35. Kennett, Patricia and Marsh, Alex. 1999. Homelessness: Exploring the New Terrain. Gran Bretaña, Policy Press. [ Links ]

36. Knapp, Martin. 2012. Mental health in an age of austerity. Evidence-based mental health, 15(3), pp.54-5. [ Links ]

37. Lankenau, Stephen E. 1999. Stronger than dirt: Public humiliation and Status enhancement among panhandlers. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 28(3), pp.288-318. [ Links ]

38. Lee, Anne F. 2002. Unpacking the Gift. In The Question of the Gift - Essays across disciplines, ed. Mark Osteen, pp. 85-101. London, Routledge. [ Links ]

39. Mauss, Marcel. 2001. The Gift. London, Routledge. [ Links ]

40. McIntosh, Ian and Erskine Angus. 1999. I feel rotten. I do, I feel rotten: exploring the begging encounter. In Begging Questions - Street-level economic activity and social policy failure, ed. H. Dean, pp.183-203. Bristol, Policy Press. [ Links ]

41. McIntosh, Ian and Erskine Angus. 2000. Money for nothing?: Understanding Giving to Beggars. Sociological Research Online 5(1), pp.1-13. [ Links ]

42. Melrose, Margaret. 1999. Word from the street: the perils and pains of researching begging. In Begging Questions - Street-level economic activity and social policy failure, ed. Hartley Dean, pp. 143-161. Bristol, Policy Press. [ Links ]

43. Merz, Eva; Bob Steadman and Alejandra Rodriguez-Remedi. 2006. Get a Fucking Job: The Truth About Begging. Edinburgh. Peacock. [ Links ]

44. MHE. 2013. Report on analysis of survey on the link between poverty and mental health problems. Brussels. [ Links ]

45. Murdoch, Alison. 1994. We are Human Too: Study of People Who Beg. London, Crisis. [ Links ]

46. Offer, Avner. 1997. Between the Gift and the Market: The Economy of Regard. Economic History Review 50(3), pp.450-476. [ Links ]

47. Osteen, Mark. 2002. Gift or commodity? In The Question of the Gift - Essays across disciplines, ed. M. Osteen, pp. 229-247.London, Routledge. [ Links ]

48. Ravenhill, Megan. 2008. The Culture of Homelessness. Aldershot, Ashgate Publishing. [ Links ]

49. Reeves, Aaron. et al. 2013. Austere or not? UK coalition government budgets and health inequalities. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 106(11), pp.432-6. [ Links ]

50. Sahlins, Marshall. 2004. Stone Age Economics. Oxford, Routledge. [ Links ]

51. Schwartz, Barry. 1996. The Social Psychology of the Gift. In The Gift: An interdisplinary Perspective, ed. Avner Komter, pp. 69-80.Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

52. Simmel, Georg. 2004. Philosophy of Money. In Philosophy of Money, ed. D. Frisby, pp. 82-90, 238-251 and 470-485. London, Routledge. [ Links ]

53. Simmel, Georg. 1950. Faithfulness and Gratitude. In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. K. H. Wolff, pp. 379-395. London, Collier-Macmillan. [ Links ]

54. Simmel, Georg. 1908. The Poor. In On Individuality and Social Forms: Selected Writings of Georg Simmel, ed. Don N. Levine, pp. 150-179. London, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

55. Taithe, Bertrand. 1996. The EssentialMayhew: Representing and Communicating the Poor. London, Rivers Oram Press. [ Links ]

56. Titmuss, Richard M. 1973. The Gift Relationship: From Human Blood to Social Policy. Harmondsworth, Penguin Books. [ Links ]

57. Williams, Terry. 1993. Crackhouse: Notes from the End of the Line. Reading, MA, Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

58. Wilson, Wendy. 2013. Homelessness in England. London. [ Links ]

59. Zelizer, Viviane A. 1997. The Social Meaning of Money: Pin Money, Paychecks, Poor Relief, and Other Currencies. New York, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]