INTRODUCTION

Migratory inflows and outflows have shaped Latin American societies for centuries. Their direction, volume and intensity have changed according to the political, economic and natural upheavals that have marked local and global history (Castles et al., 2013; Kritz et al., 1992). Starting in the 1950s, Ecuador, like many other Latin American countries, began to slowly change from a migrant-receiving country to a net migrant-sending one (Aruj, 2008). By the 1960s, many Ecuadorians began to settle in various parts of the world, including countries in the same region, such as Venezuela. This shift was fuelled by several factors: demographic transition, an accelerated urbanization process, the modernization of the local economic structures, the post-war economic boom in the US and Europe, the oil boom of 1970s, the debt crisis in the 1980s, and the financial and monetary crisis in the 1990s (Héran, 2007; Herrera et al., 2005). By 2010, about 1.5 million Ecuadorian migrants were living abroad (Chávez & Cardoso, 2010).

However, the so-called subprime crisis in 2008 marked a turning point in this process (Castles & Vezzoli, 2009). A new oil boom and the rise of Chinese loans and investment allowed Ecuador to reach some political stability and adopt an open migration policy. This, together with the fact that the US dollar has been the official currency in Ecuador since 2000, have caused this country to become a migrant-receiving nation (El Telégrafo, 2019a; Hayes, 2013). Ecuadorians living abroad began to return home, and citizens from neighbouring countries such as Peru, Colombia, Cuba and, ultimately, Venezuela started to arrive in subsequent waves (Correa et al., 2016; Moreno-Márquez & Álvarez-Roman, 2017). These new migratory flows were also fuelled by push factors in sending countries: war, violence, crime, poverty and political persecution.

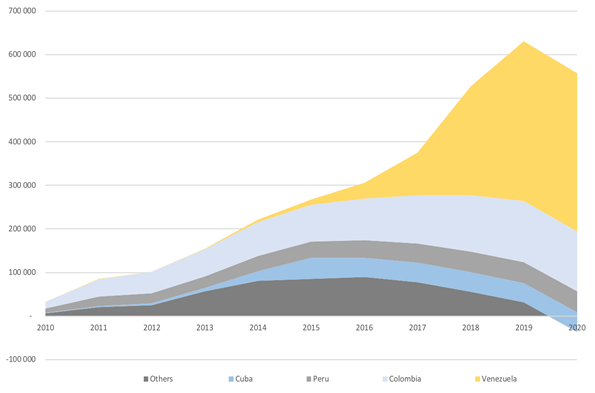

During the last decade, Ecuador has received more than 630,000 migrants. Most of them have come from Venezuela (58%), Colombia (22%), Peru (8%) and Cuba (7%). Even when Ecuador’s appeal began to diminish after 2015, the intensification of the negative conditions in neighbouring countries (i.e., Colombia’s internal war and Venezuela’s political and economic crisis) maintained the migrant inflow until the end of the decade. The COVID-19 pandemic marked a new breaking point in 2020: about 75,000 immigrants left the country in that year (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Immigration waves in Ecuador, 2010-2020

Source: Own work based on Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos [INEC], (2020a) and Ministerio de Gobierno del Ecuador (2020).

The first waves of Colombians, Cubans and Peruvians who settled in Ecuador until 2015 benefited from the momentum of a growing economy, the expansion of the local middle class and new job opportunities. This was not so for the Venezuelans who arrived in the last five years, fleeing their country in the aftermath of an economic and political crisis triggered by a decline in oil prices and the repressive reaction of its ruling authoritarian regime1. Since it is equally similar dependent on oil exports, Ecuador also entered a long recession, which triggered political changes and increased social problems. Given these adverse conditions, participants in this late migratory influx have faced more difficult times when they try to regularize their immigration status and find work and opportunities for social integration. Unemployment and involvement in informal activities became common among this population, increasing their risk of exploitation, poverty and social exclusion.

This process converged with the arrival in the country of several transnational platforms of the so-called “gig economy”. In such conditions, these platforms became a lifeline for many immigrants and their families, as they offer easy and quick access to daily income. Thus, as immigration consolidated in the country, gig economy platforms were strengthened through the recruitment of foreign workers. However, this convergence is not as convenient as it seems. It hides the existence of a shadow market of profiles that allow immigrants to circumvent the legal or algorithmic limitations imposed on them by the Ecuadorian government or the platforms, and, at the same time, it allows the latter to continue running their businesses in a grey area. This paper aims to unveil the structures of exploitation of immigrant workers created by these legal barriers, informal subcontracting practices and the platforms’ algorithmic management systems.

Therefore, this paper seeks to contribute to the ongoing discussions on the intersection of the gig economy (van Doorn et al., 2023), migration, and the precarious nature of immigrant labour (Altenried, 2020, 2023; Lata et al., 2022; Tandon & Rathi 2022). The relationship between migration, gig work, and worker protections is a complex landscape in which immigrant workers navigate the opportunities and challenges of digital platform employment. While platform work can provide immigrant workers with potential avenues to improve their livelihoods, it is crucial to acknowledge that it often comes at the cost of degraded working conditions. Digital platforms like Uber, Cabify or Rappi rely heavily on immigrant labour, taking advantage of their availability and vulnerability. The unique combination of algorithmic management and hyper-flexible employment structures in gig economy platforms creates an environment that can lead to the exploitation of immigrant workers. Addressing these systemic issues and safeguarding the rights of immigrant workers in the platform economy require comprehensive policies and regulations that prioritize fair working conditions, labour protections, and social welfare measures.

METHODOLOGY

This research started with a review of documents and previous studies on immigration in Ecuador, legal opportunities and barriers, mobility, the gig economy, fair work and algorithmic management. Considering these previous works, we decided to use a qualitative approached based on interviews (with platform workers and managers) and ethnographic observation, as follows:

From March to December 2020, we conducted 46 semi-structured interviews with workers (from six different platforms) and five platform managers.

In January 2021, we conducted 10 in-depth interviews with workers to complement the literature review.

Workers were contacted either directly through the platform or at well-known worker meeting points. The 2021 in-depth interviews with workers were carried out with the assistance of a Venezuelan Rappi worker who contacted workers on four other platforms: Glovo, Uber Eats, Cabify and Uber.

The worker sample had the following characteristics:

71% men and 29% women;

50% Venezuelan, 48% Ecuadorian and 2% Colombian;

45% aged 26-55, 21% aged 19-25; 20% aged 36-45 and 14% aged 46-68;

in terms of time spent living in Ecuador among Venezuelan workers, 40% had spent less than a year, 46% between one and two years and 14% over three years.

The data analysis considered their nationality, gender, education level, platforms, profile subcontracting, main risks, insurance, contract status, income, and working hours.

In this study, we place particular emphasis on the interviews conducted with immigrants, which constitute 50% of the sample. These interviews provide valuable insights into the experiences and perspectives of immigrant workers in the context of platform employment. Interestingly, our in-depth interviews revealed a noticeable trend among the immigrant participants: a significant proportion of them reported using rented profiles on the platforms they worked for. This finding shed light on the complex strategies employed by migrant workers to navigate the challenges and uncertainties of the gig economy. By uncovering the prevalence of a black market of profiles among migrants, our research underscores the need for further investigation into the motivations and implications of such practices within the platform ecosystem.

Migration, Unemployment, and the Gig Economy in Ecuador

The difficulty immigrants have in finding formal job opportunities is certainly related to their immigration status, but it is also a consequence of a shrinking labour market. Unemployment and informality are structural characteristics of the Ecuadorian economy. Both conditions expose migrants to exploitation and abuse.

The Ecuadorian economy is highly dependent on extractive activities and commodities (Burchardt et al., 2016). Since 2015, Ecuador has been facing an economic recession triggered by falling oil prices and rising public debt and trade deficits. This recession has increased unemployment and informal employment (Acosta & Cajas Guijarro, 2018). By 2014, among the Economically Active Population (EAP) in that country-which amounts to 8 million-49% had an adequate job2. By the end of 2019, this indicator had fallen to 38%. The COVID-19 pandemic and general lockdowns worsened this problem. By June 2020, about 84% of the population was unemployed, underemployed or working in informal activities. The situation has improved since then, but not enough to recover to the pre-pandemic state: by the end of 2020, only 32% of the Ecuadorian population had adequate employment (INEC, 2020b).

Around the same time, companies such as Cabify, Uber, UberEats, Glovo and Rappi started operations in Ecuador. Under adverse economic conditions, the arrival of these online ride-hailing and delivery service platforms became a lifeline, offering relatively easy and quick access to a daily source of revenue for both Ecuadorians losing their jobs and immigrants trying to find one.

These companies are part of the so-called “gig economy” (Friedman, 2014; Lehdonvirta, 2018; Woodcock & Graham, 2020). Enabled by the development of the internet, telecommunication networks and smartphones, as well as big data, artificial intelligence, and automation technologies-these companies have reorganized the productive process and the distribution of value in several industries on a global scale. This implies a new organization of labour based on the atomization of the productive process into micro-tasks and their distribution among a vast crowd of individual contractors. The atomization and task distribution process is ensured by algorithmic management technologies and “free market”-like information systems, which increase the labour supply massively and outsource capital and labour costs. This, together with a lack of suitable regulatory frameworks, allowed these companies to intensify their production and extraction of value added around the world.

This may explain why, in spite of the lack of infrastructure, limited connectivity and relatively weak demand for online services (GSMA, 2021; Kemp, 2020; Speedtest, 2021), these companies have decided to expand their operations to countries such as Ecuador. The lack of regulations and the availability of an increasing labour supply used to working in the grey area of underemployment and the informal market offer a window of opportunity for these companies to reap higher profits. However, after several years of unregulated expansion, they have started to face the limits of their model and social pressure for change, particularly concerning the working conditions imposed on their “contractors”, local taxes and other local regulations.

There are no official statistics on the number of people working on these applications or the migrant population involved in such activities. Nonetheless, based on data gathered from public declarations, media reports and the interviews conducted for this study, we estimate that, before the pandemic, there were about 40,000 gig workers nationwide, which represented 1% of the under-employed population (Becerra, 2019; El Telégrafo, 2019b; Universo, 2019a, 2019b). Most likely, this number increased in 2020. This assumption was corroborated during the interviews carried out for this study with several immigrants working for these platforms. Based on their perceptions, between 70% and 90% of the individuals in this labour force are immigrants.

Legal Framework and Immigration Barriers

The year 2008 became a turning point in Ecuador’s immigration policies. A new Constitution was enacted, the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR in Spanish) was created and the MERCOSUR Agreement regarding travel documents brought about a shift in legal principles and a new sense of identity and nationality in the region.

The 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution introduced the principle of universal citizenship as a new paradigm that sought free human mobility without borders, establishing that no person could be considered illegal because of his or her immigration status. For over ten years, this provision opened the door for Latin American citizens to apply for Ecuadorian nationality (Palomino, 2021)-especially those from countries that have strong barriers against migration, such as Cuba, or where there is forced displacement, such as Colombia and Venezuela.

UNASUR-created with the signing of its Constitutive Treaty in Brasilia by twelve countries3-entered into force in 2011 with the objective of building a South American identity and citizenship and developing an integrated regional bloc. The UNASUR visa was the policy instrument implemented by this organization to facilitate a regular migratory status for its citizens. Even though many countries have withdrawn from the UNASUR Treaty, including Ecuador in March 2019, immigrants entering this country can still apply for a UNASUR visa.

Finally, to consolidate the regional integration process and deepen relations between countries, MERCOSUR Members and Associate Member States4 designed a policy tool for encouraging the free movement of citizens in its territory (MERCOSUR, 2008). Each Member recognized personal identification documents as valid travel documents, passports were no longer required for citizens to move across these countries, and short-term mobility became much easier throughout the region.

Derived from these principles of universal and South American citizenship, the Ecuadorian Congress enacted the Human Mobility Law in February 2017, which established several types of naturalisation processes to acquire Ecuadorian nationality. However, in August 2018, contrary to the MERCOSUR agreement, the Ecuadorian government announced that all persons entering Ecuador must present their passport (El Universo, 2018). This measure was taken at a time when 4,500 Venezuelans were crossing the Colombian-Ecuadorian border daily, and a state of emergency was declared in three northern Ecuadorian provinces.

In July 2019, the then President of Ecuador, Lenín Moreno, issued Executive Order 826 (Decreto 826, 2019), which offered two types of regularization for the immigration status of Venezuelan citizens between July 2019 and August 2020: (i) Exceptional Temporary Resident Visas for Venezuelan citizens who were already in Ecuador and had not broken the law and (ii) Humanitarian Exception Visas for those entering the country. In both cases, Ecuador decided to recognise the validity of passports and ID cards of Venezuelan citizens up to five years after their expiration date due to delays in the issuance of such documents in Venezuela. In September 2019, based on the principle of a safe, orderly and legal migration-promulgated by the Pact for Migration-a visa was required to enter Ecuador, so the Humanitarian Exception Visa (called VERHU in Spanish) was implemented.

To find a job in Ecuador, Venezuelan citizens must have a temporary or permanent resident visa. These visas allow Venezuelans to apply for an Ecuadorian ID card. Thus far, a total of 195,560 visas have been granted to Venezuelan citizens: 128,617 issued up to August 2019 and 67,333 while Executive Order was in force (Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Movilidad Humana, 2020). President Moreno estimated that the number of Venezuelans in the country “far exceeded” the reception capacity of Ecuador, which has 17.2 million inhabitants and spends some USD 500 million on healthcare and education for migrants (El Heraldo, 2019). In this context, in September 2019, the government established a fine of USD 800 for immigrants who stayed longer than the duration of the Ecuadorian Tourist Visa, i.e., 180 days. This left around 170,000 undocumented Venezuelan citizens in Ecuador, facing significant administrative and financial barriers to regularising their immigration status.

Between 2015 and 2019, Peru and Ecuador shifted their position from facilitating the entry and regularisation of the migrant population to a border closure in mid-2019. By drastically slowing down the movement of the migrant population through border checkpoints, both governments increased the number of illegal crossings and human trafficking (Blouin & Freier, 2019). Until 2019, Venezuelan citizens could enter Ecuador freely with a passport, Venezuelan ID card or Andean migration card. The latter was granted at an immigration office when a migrant did not have any other identification document. However, since 2010, these immigrants can regularize their legal status using one of three options: the 2010 Venezuela-Ecuador Bilateral Treaty, a UNASUR visa or a work visa. The Bilateral Treaty grants resident and work visas for two years to individuals who can prove they are legally working in the country. UNASUR visas were used more widely between 2018 and 2019 to guarantee a two-year work permit without the need for a work contract. Work visas have benefited approximately 90 thousand people and can only be obtained in Venezuela or its consulates in a bordering country.

Even though Article 11.2 of the Ecuadorian Constitution grants equal rights to all, including non-citizens, this principle is not always put into practice in real life (Malo, 2020). Ecuador’s legal framework shows the contradictions and tensions between the constitutional basis of human rights and the application of restrictive policies (Acosta Arcarazo & Freier, 2015).

Structured Practices of Informal Subcontracting

There are no official data about the composition or main characteristics of the Venezuelan population in Ecuador. Nonetheless, the studies by Célleri (2019, 2020), carried out on a sample of about 6,800 immigrants in Quito, indicate that it is a young population (70% are between 20 and 50 years old), with a slight majority of men (54%), half of whom are single and most of whom are educated (40% had some college education). These studies also highlight the fact that only 20% of migrants have a legal migratory status (work visa or resident permit), which explains why only 55% of them reported having a job, of whom just less than half have a formal contract. This situation exposes them to exploitation practices and the violation of their labour rights. Indeed, 50% reported working more than the legal 40-hour week; only 12%, receiving more than the minimal legal wage of 400 USD per month; and 44%, experiencing discrimination because of their nationality. Finally, in spite of their qualifications, most of them work unskilled jobs. Under these conditions, online platforms became a relatively easy and quick alternative for many workers to obtain a daily income in the face of the crisis.

Most immigrant workers interviewed have stated that they knew a friend or family member living in Ecuador who helped them settle in the country. Social capital and network ties were transformed into key resources to gain access to employment (Massey et al., 1994). Digital platforms became part of the migration network as soon as they succeeded in offering a sustainable livelihood for immigrants.

When delivery and ride-hailing platforms arrived in the country, these activities were not regulated in any way. Therefore, they accepted Venezuelan identity documents to open a worker account, which allowed immigrants to work using their own profiles. However, as the volume of their operations grew, local governments began to push for regulations. Then, the access was restricted for new gig workers, and many immigrants could not apply for a platform account because they did not have any documentation, e.g., a work visa, an Ecuadorian ID card or a driver’s license.

As a result, immigrants started to use subcontracting to secure job opportunities. Nevertheless, this has structured mechanisms for work exploitation by transferring an entire range of risks from employers to workers, increasing the precariousness and unfairness of their working conditions.

Moreover, most immigrant workers do not have a vehicle to work with. This has opened the door for them to rent one from “investors”.

Once I finished my interview at Cabify’s headquarters, investors were standing on the sidewalk, waiting to hire drivers for their cars. I approached one of them and offered him a work system that he liked. A two-driver schedule: one from 4 a.m. to 4 p.m. and another for the remaining twelve hours. Expenses and profits were split 50/50. (In-depth interview No. 9, personal communication, January 2021)

Cabify had a list of car owners looking for drivers. Workers were free to contact them to bargain working conditions. There were two types of arrangement with them: a fixed weekly amount or 50% of the income. Based on the evidence we have gathered, this fixed weekly amount ranged from USD 75 to 100. Interviewed immigrant workers renting a car declared that they work eleven hours a day and earn approximately USD 200 a week. After paying the car rent, they are left with only 50% of their income, approximately USD 400 a month, which is the minimum wage in Ecuador for an eight-hour workday.

When platforms started to require Ecuadorian driver’s licenses and work permits, immigrant workers were forced to rent driver accounts as well. Now, they must pay for the vehicle, as well as someone else’s platform profile. According to most of the delivery workers we interviewed, those who rent profiles pay between USD 15 and 40 per week. If they rent a profile and a motorbike, they may pay up to USD 50 every week. They reported earning a weekly average of USD 190 per week, and, after deducting subcontracting costs, they can make around USD 560 a month.

And I am working with a rented account because I am not naturalized. I don’t have the identity card. I don’t have the Ecuadorian license […]. I have to pay USD 25 weekly, but you have to pay the USD 25 whether you make the money or not. (In-depth interview No. 5, personal communication, January 2021)

In the pandemic, there was an increase in motorbikes because the only steady job was delivery, but now that the pandemic is not so bad, a lot of people have quit, and that’s what they are doing, renting accounts. (In-depth interview No. 4, personal communication, January 2021)

According to Glovo’s data, 65.5% of its workers are Ecuadorian; and 34.5%, Venezuelan. They make an average of USD 3.6 per hour, and they can choose their own schedule on the platform. This is the only company that has incorporated a subcontracting clause into their terms and conditions for workers, although there is no record of this mechanism ever having been used.

The employment status of platform workers is a controversial issue. Gig workers face a difficult situation regarding labour rights, volatile income, a lack of benefits, job insecurity, and exploitation. According to the platforms, workers are considered autonomous entrepreneurs who manage their own hours and have no boss. Thus, platforms are detached from any employment relationship (Cherry, 2016; Rogers, 2015, 2016). If informal subcontracting practices are added to these conditions, workers become part of a structural chain of exploitation that makes them invisible and unprotected by the law and social benefits. Those who rent profiles are becoming labour market intermediaries for the platform, who function as active “infrastructural” agents (van Doorn, 2017), forcing workers to shoulder all the risks and responsibilities in a reconstitution of labour relations. In order to understand how these structural forms of exploitation are taking place, it is of paramount importance that we consider all the players in this subcontracting infrastructure.

Algorithmic Management and the Daily Life of a Gig Worker: How to Deal with a Toxic Relationship

The following is a common picture of the urban “gig economy”: a group of young men with orange, yellow or green square backpacks beside or on their motorbikes parked next to a shop. They talk and tease one another while checking their smartphones to see whether a new order has been placed. Their voices, way of speaking and gestures are out of tune with the monotony that surrounds them. They reveal their foreign origins. They may bother some xenophobic landlords and shopkeepers who are very happy to make money on their backs but are not willing to offer them even a parking place to wait for the next order. They are five or seven in number. Some of them have been waiting for a while; there have been no orders on their phones. Suddenly, another “motorized” (gig worker) arrives out of nowhere, takes not one but three orders and hits the road. Those who have been waiting for a long time grimace as they check their phones once again. They don’t understand. They think it’s unfair. They want to complain, but they don’t know who to complain to or even if there is someone to complain to. The veterans comfort the newcomers by saying that it is like being in a toxic relationship. Sometimes, “she” (the application) treats you well; sometimes, “she” punishes you and gives you nothing. You never know when, how or why.

Besides the questions that this description might raise from a gender perspective, which deserve a specific analysis beyond the scope of this research-this unpredictable behaviour on the part of “la tóxica” (“the toxic one” in Spanish, as some of the male interviewees refer to the application on their phones) is the manifestation of the embedded algorithms that rule these platforms and, through them, the daily lives of gig workers. Opaque and closed by design, these algorithms are the black boxes managing the platforms. They determine who receives an order, when, how, where, how much it costs and how much everyone in the chain will be paid. They also impose penalties and offer rewards in order to guarantee their supply and increase efficiency and quality of service.

But, sometimes, you arrive at a restaurant, and they take one hour, so you [waste] one hour. But Glovo doesn’t care […] at the end, they [rate] us based on what customers say. If a customer doesn’t like it, they low your score. (In-depth interview No. 8, personal communication, January 2021)

However, the complexity of this kind of global operation creates dissonance on a local scale (Friedman & Friedman, 2008). This explains why these apps are continuously updated and adapted to local conditions, creating an unpredictable relationship with workers, who try to decipher this erratic behaviour in order to maximize their rewards and avoid penalties.

So-called “algorithmic management”-a keystone of the gig economy-has been analysed by several authors. These scholars have focused on the trade-offs between (a) flexibility, autonomy and control and (b) the health and social risks associated with the generalisation of these methods of labour management and the intensification of work (Adams-Prassl, 2019; Basukie et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2015; Shapiro, 2018; Wood et al., 2019). Migration adds an extra layer of complexity to the problems workers are exposed to within algorithmic management and the gig economy, but little attention has been paid to this issue. An algorithmic score system is designed to assign rewards or penalties to the users registered in its database. These users are supposed to be the virtual avatars of concrete individuals who meet several conditions, such as being able to legally work in a given country. However, in the real world, undocumented immigrants-who, by default, are excluded from this system-have found a way in through a black market of profiles and accounts. This “intrusion” into the system calls into question the very bases and assumptions of the rating system. This sort of Pavlovian algorithm allocates, optimises and evaluates tasks and payments, aiming to provide incentives to a crowd of individual users and thus keep them working better, more quickly and more efficiently. However, the rewards and penalties that are supposed to guide individual behaviour equally may not be applied the same way to all workers.

I didn’t know how this thing work, so I asked to a colleague […] He answered, “But, my friend, you are ‘green!’... Even me, as ‘copper,’ I’m not getting any orders.” So, then, I asked: “What do ‘green’ and ‘copper’ mean […]?” He explained to me that, to get a better score, I could not stay there. Rather, I should move somewhere else. […] I had to pay the profile and the motorbike, so I took his advice and moved around the city the whole day, but it didn’t work either. (In-depth interview No. 4, personal communication, January 2021)

As shown in the example above, there is a black market of profiles and accounts among undocumented immigrants, where the incentives of the algorithmic management system are split between two or more individuals with varying backgrounds and behaviours. Hence, out of an 80-cent ride assigned by the algorithm, the actual worker receives only half that amount or less because intermediaries take the rest. Consequently, immigrant workers face the same algorithmic penalties as regular workers but receive smaller rewards. In other words, the rewards are divided among several people, while the penalties and physical effort are not. This system disproportionately affects undocumented workers, whose daily lives are conditioned by the Pavlovian machine.

Most of the interviewees in this study reported using or having used a rented account. The lack of documents such as passport, driver’s license, local residence permit or work permit is a major barrier that leads these individuals to resort to the black market of profiles. This barrier may be an indirect consequence of local authorities’ attempts to regulate these activities and force platforms to comply with local regulations, which shifts the burden of the problem from the platforms to either local governments or regulations. Nonetheless, other accounts from the same interviewees suggest another possibility. Platforms have been blocking access to new members for several months now, thus fuelling the expansion of the black market. This situation benefits platforms because they can continue to change their terms and conditions, while reducing the rate they pay to workers.

We started by creating our own account, but it was impossible […]. In fact, it has been “in process” since March. It is “in process”… Therefore, we had to rent the profile of a young guy […]. He is a good friend […]. Thanks to him, we have done well. (In-depth interview No. 7, personal communication, January 2021)

The migration variable added a new dimension to the problem of algorithmic management. Specifically, the technological black box exceeds the limits of the platform on which it exists. The grey areas created by migration and failed regulations increase the potential for algorithms to discipline not only those in their databases but also those who are not registered.

Under the Apps, Humans! Behind and Beyond the Algorithms

Over the past two decades, the gig economy has been associated with technological development in several fields, including telecommunication networks, mobile phones, big data processing, artificial intelligence, e-commerce and finance. The opacity of the algorithmic management technologies that power these platforms has created an illusion of a highly automated industry. However, many researchers have demonstrated that most of these new industries based on artificial intelligence and other data-driven technologies still rely heavily on non-automated human labour (Casilli, 2019; Bouquin, 2020; Le Ludec et al., 2020; Tubaro et al., 2020). In addition, the phenomenon of migration has put human labour, which is the basis of the gig economy, under the spotlight. The analysis of this phenomenon has shed light on the ways locals and migrants appropriate, reinterpret and modify the new technological regime imposed on them by the platforms.

Two stories told by immigrant gig workers during the interviews illustrate how the functioning of platforms in peripheral contexts such as Ecuador still depends on social practices and interactions beyond algorithms. Moreover, these immigrant workers have identified glitches in the algorithms and used them to their advantage.

Despite their contrasting perspectives, platforms and immigrants have something in common: they are newcomers taking a chance in a new land. The former will do whatever it takes to start operations: infrastructure investments, legal procedures and shortcuts, advertising, and political lobbying. The latter, with far fewer resources and greater restrictions, will devote their physical and mental effort to move forward. For most of them, looking back is not even an option.

We came to work. We are concentrated. It also happens in Venezuela. The people who worked there are the immigrants […] We came with a mentality to work because we need to grow […], pay our debts and all that. (In-depth interview No. 3, personal communication, January 2021)

These two different but converging wills explain, to some extent, the large number of immigrant workers on online platforms. They provide an easily accessible source of income and allow people to work “as much as they want”. This is precisely what platforms need: cheap and flexible labour willing to work unlimited hours without demanding the same social benefits as other local workers. Nonetheless, before starting this “synergistic” relationship, most recently arrived platforms had to surmount two barriers: the limited access of immigrant workers to means of production (cars, motorbikes, bicycles and mobiles) and the risks associated with operating in a grey, unregulated or even illegal area. In both cases, platforms have had to switch to “manual” mode and do considerable offline and lobbying work to make their algorithms operate properly.

Cabify’s intermediation practices between drivers and “investors” demonstrate that the first online ride-hailing platforms started operating like any agricultural or building contractor: looking for day labourers on the street. Initially, most of these platforms opened offices to recruit potential candidates and provide them with promotional and training talks. They lobbied and reached informal agreements with workers, investors and authorities. All these offline and in-person steps were crucial for the startup processes of these companies. Once the early adopters were established, the platforms conducted less of these activities. However, they continue to be the basis of the black market of profiles. As mentioned above, this black market introduces a glitch into the algorithmic management system, reducing the actual income immigrant workers receive at the end of the chain.

Furthermore, driven by their needs and hopes, immigrants are all but passive subjects in The Wizard of Oz. Working more than ten hours a day, they follow his rules; they try to comply with his algorithmic management; they even pay for his mistakes; but they also try to understand him, learn from him and, when they can, pull back the curtain and fool him.

When I started, a friend of mine had Cabify, [I live near the airport] so my friend and I set up a sort of “centre” […] We made a virtual queue with several phones and I watched them. The others worked with their cars at the airport […] I accepted all the rides that I could on those phones, and I called them. The first one at the transfer point would open the app on another phone and pick up the passenger. […] I know the applications very well because, since I arrived here, I’ve been working with Uber, Cabify, InDriver, all of them. (In-depth interview No. 1, personal communication, February 2021)

A normal Cabify worker in the city can make up to USD 300 per week. However, once I took a ride to the airport (the platform was just starting), and I received a [booking] from Guayaquil-a client who was coming on a flight from Guayaquil. I understood that I might receive a [service] while outside the airport. We didn’t know that at the moment. The next time I took a ride to the airport, I got another [booking]. We made USD 2.000 per month. (In-depth interview No. 5, personal communication, February 2021)

This act of technological appropriation and reinterpretation, of turning the algorithm to their advantage, shows that workers, particularly immigrants, can resist algorithmic management (Albornoz, 2020; Bijker, 1995; Oudshoorn & Pinch, 2005; Silverstone & Hirsch, 1992). This new trend is fuelled by the same force that made these people flee their country with everything they had to start a new life far from their homes. This is probably the specificity that the migratory variable can introduce to the understanding of the process of local appropriations of technologies.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

During the last decade, Ecuador has received over 500,000 immigrants from neighbouring countries, especially Colombia and Venezuela. This inflow can be attributed to attractive factors such as flexible immigration policies and a dollarized economy, as well as to negative conditions in the countries of origin, including war, violence, crime, poverty and political persecution. However, the economic recession and political changes over the past five years have attenuated these attractive factors and created more barriers for immigrants who want to settle in Ecuador and engage in their economic activities.

Within the same period, gig economy platforms have emerged as an accessible work and income-generating option for this migrant population. However, gaps in local regulations and the operation of these platforms have created grey areas where undocumented immigrants can secure work and income, but at a high risk of exploitation and exposure. These grey areas are the result of the subcontracting structure established by the black market of profiles and algorithmic mismanagement.

Examined through the lens of the Fairwork Principles (Graham et al., 2020), these grey areas pose new risks for immigrant workers:

Fair pay. Even when the platform pay is higher than the local minimum legal wage, once workers start renting a profile, their income is significantly reduced. Most workers are expected to work over 40 hours per week and pay a significant portion of their earnings to the profile owner. Therefore, immigrant workers are paid less than regular Ecuadorian workers for the same amount of work.

Fair conditions. Unlike most platforms, Glovo maintains accident insurance for their workers. However, it cannot be used by workers with rented profiles, which leaves their well-being and safety at stake, without any protection from the platform.

Fair contracts. Many immigrant workers have no access to contracts because they belong to account owners, which prevents them from having any legal status on the platform. They are invisible and have no legal rights, which places them in a situation of vulnerability and job insecurity.

Fair management. Immigrant workers with rented profiles are exposed to an unbalanced and unfair algorithmic management system, where rewards are shared among various individuals, while penalties are incurred only by the actual workers. They must not only keep a high rating for a profile that is not theirs but also recoup or pay for the losses of other profile users. The existence of a black market of profiles creates subcontracting structures that allow platforms to keep labour prices low without any managerial accountability.

Fair representation. Thus far, platforms have avoided creating collective representation and worker voice mechanisms. Therefore, workers lack the ability to collectively bargain, and their demands continue to be resolved on individual terms. However, if a collective organisation were to be created, subcontracted immigrant workers would not be able to formally join it. Nonetheless, as evidenced by several international protests held in 2020 (Howson et al., 2020), there exist informal organisations and other forms of resistance.

The various forms of technological appropriation, reinterpretation and negotiation within the algorithms behind the platforms can be leveraged to benefit workers.