What do we know about this topic?

One of the hurdles for implementing the ADD in the clinical setting is the lack of institutional forms that facilitate the implementation of the document by users. In Colombia, we don't know whether the existing ADD forms meet the legal requirements and have a relevant content for end-of-life medical decision-making.

What are the new contributions of this study?

The ADD forms of the participating pain and palliative care institutions have a low content in terms of the rights that may be listed in the ADD, in accordance with the current scientific literature available.

The study summarizes the legal, ethical and clinical criteria for developing or improving the institutional ADD forms. The findings support the development of a structured form, validated by the palliative care associations in Colombia.

INTRODUCTION

The Advance Directives Document (ADD) is an increasingly relevant ethical tool in healthcare. Although Advance Directives (AD) fail to provide all the answers, or the most accurate answers for every clinical setting, for each problem or conflict in the care or incompetent patients 1,2, advance directives are a valuable guideline for the end-of-life (EoL) medical decision-making process, supported by the respect for the individual under the principle of prospective autonomy. 3,4

Some are in favor of ADDs developed without a standard form. The drawback is the quality of the content and the inaccurate drafting. 5 Other obstacles have been identified in this scenario for respecting and fulfilling the ADs, including the concern of the physicians about the legal validity of the ADs, the lack of clinical relevance, and the request for unreasonable or futile treatments. 6 Additionally, there is evidence of the limited impact of the ADD in clinical practice. 5,7,8 Notwithstanding these factors, the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) has suggested the development of institutional forms to facilitate the process to users and to increase the rate of ADD completion within the Advance Directives Planning programs. 9

In Colombia, the right to sign the ADD is approved under Law 1733 of 2014 10 and the rules for the drafting of the ADD are governed by Resolution 2665 of 2018 of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection. 11 There are three options to formalize the ADD: before a notary, before the attending physician, or before two witnesses, and each has to comply with a number of valid legal requirements. 11 Previous studies report a low rate (10.5 %) of institutions with ADD forms. 12 However, we don't know whether the existing ADDs are legally valid and have relevant information to be of value for EoL medical decision-making. The purpose of this study was to describe the contents of the ADD used in the pain and palliative care services in Colombia.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study was designed. A non-probabilistic sampling was used, including an invitation to the Colombian Association of Palliative Care (ACCP), The Association of Palliative Care of Colombia (ASOCUPAC), and the Colombian Observatory of Palliative Care (OCCP). The data collection strategy comprised two stages: first, each association distributed the invitation twice, with a one-week interval, to the e-mails of the professionals and health institutions affiliated and registered in their databases as of May 31st, 2022. A public invitation was also issued via the webpage of each association. The second phase involved a telephone call as a reminder to ensure participation.

The forms were collected between June 1st and August 31st, 2022. To be eligible, all the ADDs complied with the voluntary participation authorization by sending the forms to the investigators institutional e-mail. Any ADDs forms with illegible text or defective printing were excluded from the study.

One of the investigators (CLBM) that did not participate in the assessment of the forms, was responsible for ensuring confidentiality by erasing the logo and assigning a numeric code to each form. Then CLBM developed an anonymous database with the study sample and each form was only identified by its code throughout the investigation process.

Two investigators (AMÁA and ACV) independently evaluated a copy of each anonymous form using a printed checklist (Table 1). Any disagreements in the evaluation were solved via a discussion between the two reviewers who reached a consensus decision. If the disagreement persisted, the CLBM would make the final assessment but this was never required.

Table 1 Checklist for assessing the content of the ADD forms.

| N.º | Variables | Compliant | Observations | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| 1 | Minimum content | Article 4, Resolution 2665 of 2018 11 | |||

| City and date the document was issued | |||||

| First and last name and ID number of the deponent | |||||

| Specific and concrete indication that he/she is of sound mind and free from coercion and that he/she is aware and informed of the implications of his/her statement | |||||

| Signature of the respondent | |||||

| 2 | The form requires notarization | Article 6, Resolution 2665 of 2018 11 | |||

| 3 | The form provides for formalization before two witnesses | Article 7, Resolution 2665 of 2018 11 | |||

| 4 | The form provides for formalization before the attending physician | Article 8, Resolution 2665 of 2018 11 | |||

| 5 | The respondent can indicate personal pathological history and there is an open text space to add an answer | 1,14,15 | |||

| 6 | Considers or suggests critical emergency clinical scenarios to identify specific patient goals and preferences | 9,13,14,16 | |||

| 7 | Asks the patient about any other medical preferences not mentioned and there is a blank space to write the answer | 9 | |||

| 8 | Considers or suggests a value scale history | 14,16 | |||

| 9 | Asks about values and preferences for EoL and there is a blank space to write the answer | 9,14 | |||

| 10 | Asks about their quality of life concept and there is a blank space to write the answer | 12,14,16 | |||

| 11 | Asks about their interpretation of a dignified death and there is a blank space to write the answer | 14,16 | |||

| 12 | Asks whether he/she would like EoL palliative care | Law 1733 of 2014 10. Articles 9 and 13, Resolution 0971 of 2021 18 | |||

| 13 | Considers the personal decision to become an organ donor for transplantation, education or research purposes | Paragraph 1, article 4, Resolution 2665 of 2018 11,13,14,16 | |||

| 14 | Considers the patient’s request for the right to die with dignity via euthanasia and there is a blank space for the patient’s description of the applicable clinical scenarios | Articles 6 and 14, Resolution 0971 of 2021 13,14,18 | |||

| 15 | Gives the patient the option to write the name of his or her legal representative before the medical team (one or more surrogates in order of priority) | 13,14,16,18 | |||

| 16 | Allows the patient to write down the names of people who will be excluded from making health care decisions | 16 | |||

| 17 | Inquires about the choice to stay at home during EoL | 13,14 | |||

| 18 | Inquires about the right to ask for spiritual and moral support in accordance with his/her believes and needs | 13,14 | |||

| 19 | Asks the patient about any after death wishes | 14,15 | |||

| 20 | The form has an instructions annex as a supplement | 14 | |||

Source: Authors.

Content analysis

The variables for content assessment were the rights described in the scientific literature 1,9,12-16,18 and in the national legislation 10,11,17 that may be included in the ADD, up to the study date. The legal validity data for the ADD are listed under Resolution 2665 of 2018 of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, which describes the minimum content and the requirement to formalize the document before a notary, or before the attending physician, or with the participation of two witnesses. 11 Based on the aforementioned conceptual framework, a checklist was developed (ÁMAA), reviewed and approved (CLBM & ACV) which included 20 variables, classified into legal, clinical and ethical criteria (Table 1). Each study variable was rated as "compliant: yes/no" to define whether the variable was present (yes) or absent (no).

The checklist was tested through ADD forms on public access websites. The following terms were used in the Google's search engine: form, ADD and Colombia. There were no changes in the form's variables. In the absence of a validated scale to assess the quality of the ADD forms in the scientific literature, the investigators used a predefined scale to describe the general contents of the form, as follows: Low content (less than 50 %, if they included 10 or less of the 20 variables suggested in the study); Medium content (between 50 % and 75 %, if 11 to 15 variables were included); and High content (more than 75 %, if more than 15 variables were included).

Statistical analysis

Double tabulation (AMÁA and ACV) and verification of consistency between the two databases was performed using Microsoft Excel®. The statistical analysis was performed in the Stata® 17.0 program. Qualitative variables were described by means of absolute and relative frequencies and the analysis was completely descriptive.

RESULTS

A total of 24 ADD forms from various cities in the country were collected and analyzed (Complementary content 1). In view of the numerous mailing lists of practitioners and institutions from the different participating associations, it was impossible to estimate a response rate. Table 2 shows the presence or absence of the study variables for content analysis.

Table 2 Frequency of compliance with the study variables in the participating ADD forms.

Source: Authors.

General content of the forms

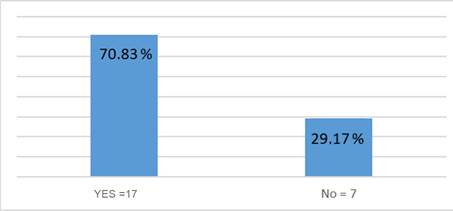

The largest number of variables considered in a form was fourteen (n=14/20). None of the forms included all of the 20 proposed study variables; 70,8% (n=17/24) of the forms included fewer than 10 variables and 29.2% (n=7/24) of the forms included between 11 and 15 of the variables suggested for analysis (Table 3). Half of the forms were written in closed text and the other half were mixed forms with closed text and blank spaces.

Legal criteria

Only one of the 24 forms failed to meet the minimum content requirements (n=1/24). This form authorized a family member or a legal representative to draft an ADD on behalf of the patient. Four of the forms were not formalized at the end of the text and hence are not legally binding.

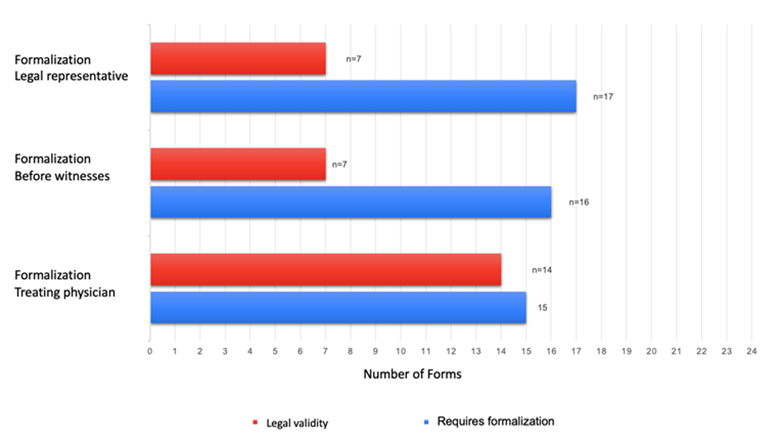

Sixteen of the 24 ADDs were formalized in front of witnesses, but only seven (n=7/16) met the legal validity criteria. The formalization of the ADD before witnesses meets the legal validity when: the two witnesses are free of inabilities to assume the position of guarantor, identify themselves and subscribe the ADD in the same terms required for the grantor according to article 7, Resolution 2665 of 2018. 11

The formalization of the ADD before a physician was found in 15 of the 24 participating forms, of which, fourteen forms (n=14/15) met the criteria for legal validity. The formalization of the ADD before a physician must bear the names, surnames, medical registration number and identification document of the treating physician in addition to the physician's signature; no witnesses are required (Article 8, Resolution 2665 of 2018).

The legal validity of the ADD before a notary is fulfilled when the document is formalized through a public deed. (11

Seventeen of the 24 forms analyzed in this review consider the appointment of a legal representative specified in the document; however, only 7 (7/17) require the signature of the legal representative to validate the document (Figure 1).

Specific advance directives

The concept of quality of life was explicit in the text of the form, and the patient did not have the option to accept or reject the definition adopted by the institution in eleven forms, while only four forms provided a blank space to submit personal opinions. Likewise, the definition about the right to palliative care was included in the text of 17 forms, but only five (n=5/17) had a yes/no option for the patient to accept or refuse (Figure 2),

Fourteen forms (n=14/24) ask for acceptance or refusal of the general preference for organ donation, but only four forms (n=4/14) give the option to choose the purpose of the donation: transplantation, scientific research or teaching (Table 2).

Of the 24 ADD forms in this review, 7 forms (n=7/24) discuss the right to die with dignity through euthanasia, giving the patient the choice (yes or no) but only 4 forms (n=4/7) presented pre-established concrete and clear clinical scenarios in the text. However, the forms did not provide blank spaces to add other clinical scenarios and only one form considered the continuation of the protocol and performance of euthanasia if it was previously in process.

Additionally, none of the forms included a reference to history of diseases, the patient's opinion about dying with dignity, values, or names of the persons that should be excluded from medical decision-making. Finally, the assessment of the forms identified some emerging variables which were not considered in the study (Table 4).

Table 4 Variables emerging from content assessment of each form.

| N.º | Variables | Considered in the form n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| 1 | Educates on the right to revoke the ADD | 7 (29.17) | 17 (70.83) |

| 2 | Continue and administer euthanasia if previously accepted under the death with dignity protocol | 1 (4.2) | 23 (95.8) |

| 3 | Provides for conscientious objection or medical refusal to comply with the AD and transfer of the AD to another professional | 5 (20.83) | 19 (79.17) |

| 4 | Provides for the temporary suspension of the AD in the event of pregnancy | 3 (12.5) | 21 (87.5) |

| 5 | Provides for the right to authorize family members and/or third parties to access the medical record | 2 (8.33) | 22 (91.67) |

| 6 | Asks the patient whether he/she wants to participate in clinical research or scientific protocols | 1 (4.17) | 23 (95.83) |

Source: Authors.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that the ADD forms used by the participating pain and palliative care institutions in Colombia have a low content, based on the rights included in the ADD, according to the scientific literature available up to the date of this study. There are no validated instruments to assess the quality of the ADD forms. However, on the basis of the criteria used, the content analysis highlights some deficiencies with regards to the legal validity, the lack of information regarding clinical and ethical variables and the opportunity to include additional directives or individual preferences.

The legal validity requirements of the forms are more easily met by formalizing the ADD with the participation of the attending physician. It should be noted that the patient is the only person who can prepare and sign his/her own ADD (11,19. The forms that provide for the appointment of a legal representative require the signature of the latter to confirm acceptance, the actual existence of the ADD, the understanding of the AD by the signatory and the legal validity of the document. 17,20) Moreover, only if the ADD meets the legal validity criteria 4,11 the ethical criteria are then analyzed. 3 In this regard, published studies show that if the physician has any concerns about the legitimacy of the ADD, he or she may use his/her clinical judgment which may or may not be aligned with the individual's preferences. 6,19 The results of this study highlight the opportunities for improvement of the forms, supported by continuing medical education to clarify the conceptual, clinical, ethical and legal aspects of the ADD in the country. 12

In contrast to the clinical variables, little consideration is given to the ethical variables in the forms. Ethical conflicts at the EoL in the physician - family and physician-physician relationships may be avoided if the ADD considers aspects such as quality of life, death with dignity, the right to die with dignity through euthanasia, and patient's values. 21 Consideration of the patient's values is a valuable approach for decision-making in the absence of an ADD or when the ADD fails to address specific questions. 15,16) The ADD and the patient's values within the framework of an Advance Directives Planning Program generate trust, strengthens the ethical validity and the binding nature of the ADD from the physician's perspective, which is essential since the physician is actually responsible for implementing the AD. (3

The lack of adequate forms for the patient and easy access to the completed ADD for the physician have been identified a issues for implementation. 9,19,22,23. Similarly, there is a clinical applicability hurdle in case of legal validity issues 19 and problems with the content of the ADD. 5,6) For instance, in Australia, a recent national multicenter audit of completed ADDs identified some flaws in terms of access to the forms, completion by the patient, and legal quality, which represented an issue when endorsing a medical decision, and could in fact be considered a medical error. 19

The right to sign an ADD 11 should go beyond just providing a standard form. 24 Studies have shown a poor knowledge about specific clinical situations and the impact of such decisions on medical therapies when the ADD is completed by the patient out of his/her own will, without the physician's involvement. 20 Therefore, both the institutional and the physicians' efforts shall focus on the implementation of Advance Directives Planning Programs 6,9,25,26 to ensure informed decision-making, which may or may not include the drafting of an ADD. 9,24,27,28 From this perspective, the standard form may be used as a valuable ethical and clinical tool to introduce, guide and assess the conversations and decisions of EoL care. 9,24

This document represents an initial structured evidence for the scientific literature, which evaluates the quality of the ADD contents in accordance with the legal, ethical and clinical variables of the pain and palliative care units in Colombia. The literature provides evaluation reports based on legal quality indicators of ADDs completed at healthcare institutions by Buck et al. and on-line ADD templates by Luckett et al., both in Australia. 19,23 Other authors analyze the quality indicator under legibility criteria 29,30 showing that the ADD is beyond the average comprehension of adults, both in the United States and in Canada, hence hindering a proper understanding of the implications and consequences of the decisions made by the patient with regards to EoL care.

The limitations of the study include the sample size and the fact that the participants were recruited using convenience sampling which compromises the generalization of the results due to the uncertain representation of all the ADD forms available in the country. This phenomenon is primarily the result of the voluntary participation of the institutions and of the usual skepticism when participating in sensitive issues with private documents, despite the guarantee of anonymity and the academic nature of the results. Likewise, improving the quality of VAD forms involves much more than just adjusting the content; it must ensure that the text and visual design are understandable to patients according to the level of health literacy in the country. 24,20,30-32 In this regard, the authors felt that the legibility analysis of the forms warrants a separate study design. Formatting characteristics (e.g., font size and spacing, word length, graphics, layout), which could affect the legibility and quality of the forms, were not assessed.

A future study is suggested for the design of a single form structured by palliative care medical associations. A second study should evaluate the external validity or applicability of the standard form designed for a population group in a multicenter study, in addition to assessing its value for Advance Care Planning Programs and in terms of quality of EoL care from the perspective of patients, family members and physicians. Healthcare Provider Institutions (IPS) and Health Promoting Entities (EPS) are advised to include a form available on their official websites 23 and integrate the completed ADD with the electronic medical records. 9,22 Ideally, international palliative care institutions should consider creating a conceptual framework of criteria and recommendations for the development of ADD forms that can guide clinical practice and research 9,23. Finally, a study should be undertaken in Colombia to characterize the implementation of Advance Care Planning Programs.

CONCLUSIONS

The results show deficiencies in the content of the ADD forms used in the participating pain and palliative care services. In Colombia, a single standard national form is required based on the joint efforts of Universities and Palliative Care Medical Associations.

ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Ethics Committee approval

The Ethics and Research Committee of the School of Medicine of Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS) approved the study through Minutes 657 dated June 1st, 2022.

Protection of persons and animals

The authors state that no experiments in human beings or animals were conducted for this research.

text in

text in