Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

Print version ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.17 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2015

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.1.a08

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.1.a08

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Language configurations of degree-related denotations in the spoken production of a group of Colombian EFL university students: A corpus-based study

Configuraciones lingüísticas de las expresiones de grado en la producción oral de un grupo de estudiantes universitarios de inglés como idioma extranjero en Colombia: un estudio basado en corpus

Wilder Escobar1

1 Universidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia. escobarwilder@unbosque.edu.co

Citation / Para citar este artículo: Escobar, W. (2015). Language configurations of degree-related denotations in the spoken production of a group of Colombian EFL university students: A corpus-based study. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 17(1), pp. 114-129

Received: 27-Nov-2014 / Accepted: 13-Apr-2015

Abstract

Developing the competences needed to appropriately use linguistic resources according to contextual characteristics (pragmatics) is as important as the culturally-imbedded linguistic knowledge itself (semantics), and both are equally essential to form competent speakers of English in foreign language contexts. As such, this investigation relies on corpus linguistics to analyze both the scope and the limitations of the sociolinguistic knowledge and the communicative skills of English students at university level. To this end, a linguistic corpus was collected from spoken production of EFL learners, compared to an existing corpus of native speakers, and analyzed in terms of the frequency, overuse, underuse, misuse, ambiguity, success, and failure of the linguistic parameters used in speech acts. The findings herein describe the linguistic configurations employed to modify levels and degrees of descriptions (salient semantic theme exhibited in the EFL learners' corpus). The study discovered problems regarding the students' production in terms of wrong word choices or forms, faulty word combinations, and incomplete or unsystematic structuring of expressions. It concludes that expressions aiming at conveying or modifying degree are complex and should be viewed as units which require modeling for a better appropriation of an in-context understanding of its linguistic use which corpus can assist.

Keywords: communicative competence, corpus linguistics, intensifiers, pragmatics, semantics

Resumen

Al reconocer que el desarrollo de competencias necesario para utilizar apropiadamente recursos sociolingüísticos según las características contextuales (pragmática) es tan importante como el conocimiento cultural implícito en el lenguaje mismo (semántica) y que los dos son equivalentemente esenciales en el proceso de formación de hablantes de inglés como lengua extranjera, esta investigación se basa en la lingüística de corpus para analizar tanto los alcances y las limitaciones del conocimiento sociolingüístico como las habilidades comunicativas de estudiantes universitarios de inglés. Para tal propósito, se creó un corpus lingüístico de la producción oral de estudiantes de inglés, se comparó con un corpus existente de hablantes nativos y se analizó en términos de frecuencia, uso, ambigüedad, éxito y fracaso de dichas convenciones lingüísticas en actos de habla. Los hallazgos abordan las configuraciones lingüísticas empleadas para modificar niveles y grados de descripción (un patrón semántico significativo en el corpus de los estudiantes). El estudio devela problemas asociados a la selección léxica e inflexiones correspondientes, combinación inadecuada de palabras, y la estructuración asistemática de expresiones. Concluye que las expresiones que expresan o modifican grado deben ser vistas como unidades lingüísticas y que la lingüística de corpus puede ofrecer grandes beneficios proporcionando modelos de uso en contexto y para propósitos específicos.

Palabras Clave: competencia comunicativa, intensificadores, lingüística de corpus, pragmática, semántica

Introduction

The geographical distance of Colombia from English-speaking social environments suggests a separation between English learners and the sociocultural elements that create, form, configure, and transform their target language. This estrangement fosters false and misleading impressions about the pragmatic patterns of English use which are, in turn, reproduced in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) textbooks, EFL materials and teaching aids used by teachers, students, and other stake holders in the EFL teaching-learning endeavor. Such language misrepresentations severely constrain the opportunities for learners to experience the common culturally-established conventions and collectively-exercised language arrangements obstructing pragmatic development in EFL such as word choice, word combinations, the configuration of expressions, and so on, which, aid the attainment of communicative functions. In this regard, the functional approach to corpus linguistics presents alternative means to understanding the configuration of linguistic structures in terms of the communicative function they achieve, the level of achievement and/or the potential they have to achieve them (Meyer, 2002).

In the outset, a major setback in the acquisition of English sociolinguistic conventions for Colombian learners is that Colombia shares its official language with most of its neighboring countries, hence limiting the need to use English as the lingua franca for trade or mobility in tourism, education, or work among South American travelers. This situation deprives language learners of the great opportunity afforded to their European counterparts to access, acquire, and appropriate socio-cultural information regarding language use directly and spontaneously through the everyday interactions that the characteristics particular to the European context require. Despite such lack of opportunities to use English for naturally occurring communication, Colombian educational policies display a growing concern for teaching English as a Foreign Language grounded on the prospects of participating in the globalized dynamics of the academic, professional, and sociocultural exchange (MEN, 2004; 2006a; 2006b; 2007).

In addition to the rather limited opportunities to use English for social interaction, teaching practices and resources often oversimplify and standardize speaking patterns falling short of accurately representing naturally occurring interactions.

- At the societal level, communication usually patterns in terms of its functions, categories of talk, and attitudes and conceptions about language and speakers. Communication also patterns according to particular roles and groups within a society, such as sex, age, social status, and occupation […] Ways of speaking also pattern according to educational level, rural or urban residence, geographic region, and other features of social organization. (Saville-Troike, 2003, p.11)

These patterns deviate from the prescriptive grammars of traditional English teaching and the overgeneralized speaking patterns presented in books and software programs (King 2007; Nguyen, 2011; Recski, 2006).

Expressing and modifying degree is no exception to this generally existing problem. Even though the use of intensifiers represents a referent against which EFL proficiency can be assessed, it is often oversimplified, generalized or misrepresented, at best, or completely overlooked at worst. Intensifying verbs, adjectives, and adverbs is a function that requires complex language configurations, and the blending of their constituting bits and pieces is socially-governed (Altenberg, 1991; Kennedy, 2003; Liang, 2004). However, words associated with these expressions of degree are routinely addressed in isolation from their sociolinguistic makeup rather than through referents after which such socially established patterns of language use can be modeled.

A popular, although erroneous conception of the systemic relationship among language, cognition, and the social human is that the linguistic system operates independently of the others and, as such, grammatical rules precede and govern social aspects of language, obscuring the reciprocal influences where society forms, and transforms language, and language, in turn, constructs society— all of this in the daily sociocultural exchange (Escobar & Gomez, 2010; Parodi, 2005; Spolsky, 1998). In Sinclair's (1991) words:

Starved of adequate data, linguistics languished – indeed it became almost totally introverted. It became fashionable to look inwards to the mind rather than outwards to society. Intuition was the key, and the similarity of language structure to various formal models was emphasised. The communicative role of language was hardly referred to. (p. 1)

With that in mind, corpus linguistics looks outwards to society's language use examining samples drawn from uses in real-life contexts (McEnery & Wilson, 1996). Hence, "corpora can be invaluable resources for testing out linguistic hypotheses based on more functionally based theories of grammar, i.e. theories of language more interested in exploring language as a tool of communication" (Meyer, 2002, p. 2). One of the advantages of corpora over other resources is that speech is natural and the findings in corpus linguistics studies often clarify misconceptions and consider possibilities often ignored in traditional English teaching (Aston, 2000; Recski, 2006; Véliz Campos, 2008; Viana, 2006). In this sense, "corpora are much better suited to functional analysis of language: analysis that are focused not simply on proving a formal description of language but on describing the use of language as a communicative tool" (Meyer, 2002, p. 5).

A greater appreciation for the benefits that the use of corpora offers to the EFL classroom could lead to the teaching of discursive strategies which enhance students' competence in communicative situations in EFL by eventually motivating metacognitive and autonomous processes informed by their own use of corpora. That is, empowering teachers to use widely accessible resources like corpora in the quest for a less intuitive representation of natural language use, on the one hand, and getting students acquainted with those same resources to inquire about language and self-monitor their process, could improve EFL development.

In this regard and within the broader scope of language functions, the present article focuses on examining and describing ways in which a group of EFL learners configures language to achieve the particular communicative goal of expressing and modifying degree, their level of attainment, and the potential their linguistic configurations pose to communication when compared to the natural use of English given by native speakers analyzing frequency, comparing patterns, and characterizing differences. The following questions guided the research process:

- What degree-related linguistic configurations can be characterized from the spoken production of a group of EFL university students? How do the degree-related linguistic configurations compare to the configurations employed in the corpus of native English speakers to achieve similar functions?

Literature Review

Conceptually speaking, there are different types of principles governing the use of language in daily interactions (Pütz & Neff-van Aertselaer, 2008) including semantics, which studies literal meanings of words, phrases, and sentences in isolation (out of their context). It attempts to describe and comprehend the processes behind the configuration of language to create and elaborate meaning from simple structures to more complex ones, thus employing the knowledge one possesses about the language itself (Griffiths, 2006; Portner, 2006).

Pragmatics, on the other hand, is concerned with the social exchange of language under contextual conditions and discursive situations for communicative purposes, particularly in relation to social functions in specific networks: the study of the speaker's intended meaning, the interpretation of the utterance as well as the implications of contextual factors in the shaping of meaning. That is to say, pragmatics does not only focus its attention on one specific aspect of meaning, i.e. the producer of the message, or the word or utterance, or the receiver, or the context, but it studies the inferences that the interrelating dynamics among the aforesaid elements have on the levels of the meaning achieved. The first level is abstract and refers to what a word or a sentence may signify; the second is contextual, referring to assigning sense and reference to that word or sentence. Finally, the third level is the force of the utterance and represents the speaker's intended meaning (Thomas, 1995). Accordingly, Griffiths (2006) proposes three stages of meaning interpretation: literal meaning which displays the semantic information one may have of English; in the present case, in addition to the semantic knowledge, explicature stage also unveils contextual characteristics to interpret ambiguous utterances such as 'work out' which could take on numerous meanings contingent to context. Finally, the implicature stage goes even further into analyzing the intentions, relationships, body language, and contextual cues all together to identify specificities on meaning and denotations.

Conversely, Kasper (2001) addresses pragmatics from four perspectives, the first of which is a communicative perspective that elaborates the pragmatic individual as an autonomous factor which acts on its own and as a contributing factor with its own grammatical knowledge. The second perspective addresses pragmatics as a process of information which emphasizes the role of attention and metacognition. The third perspective is sociocultural and refers to the knowledge and proper implementation of the rules and regulations of a socio-linguistic community. The fourth is socialization, investigating language as pragmatic and cultural knowledge acquired simultaneously through active participation and interaction.

Competence in a foreign language includes the degrees of sociocultural knowledge an individual acquires, understands, appropriates, and exhibits in order to reach a level of 'effectiveness' in communicative performance. In other words, it is the knowledge that enables an individual to express intentions and negotiate meaning in context and, appropriately, through speech acts. This knowledge involves two things: having the means to express speech acts, and the socio-cultural understanding of any limitations that may arise in their use (Canale, 1983). As far as developing pragmatic competence in foreign languages, it is particularly difficult because languages evolve and are culturally constructed (Nguyen, 2011). That is, communities design code systems mediated by cultural elaborations which, in turn, generate very significant differences between the grammatical rules and the socio-linguistic principles governing language use.

Schumann (1978) also takes social and psychological distance from the target language as a high-impact factor in the development of the communication skills in question. He explains that the greater the distance from the language in use, the weaker the grasp of the language and its token grammatical and social uses. Consequently, we must turn to other disciplines that support the processes of understanding and using language. Schmidt (1983) suggests that these disciplines include pragmatics, discourse analysis, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, and ethnography, inter alia. Accordingly, Canale (1983) and Canale and Swain (1980) propose a scheme of four universal competencies required for an individual to become competent in the use of language which encompass (1) grammatical competence: the skills with vocabulary, word and sentence formation rules, linguistic semantics, pronunciation and orthography, and language code information as such; (2) sociolinguistic competence: skills in producing and understanding language appropriately in different sociolinguistic contexts depending on factors such as the gender, status, or age of participants, the purpose of the interaction, and/or the standards or conventions of conversation in a given situation; (3) discourse competence: skill in using grammatical forms and their meanings or representations to make unified, coherent spoken or written texts; and (4) strategic competence: verbal and nonverbal skills used to prevent a breakdown in communication caused by performance factors such as not being able to remember a word, maintaining one's turn in the conversation, losing one's train of thought, etc.

This brings to mind the newly-constituted discipline known as "ethnography of speaking," in which Hymes (1971, cited in Bauman & Sherzer, 1975) explored various factors involved in communication such as linguistic repertoire, genres, acts, frames, speech events (the point at which participants enter into contact using language, where the activity occurs and takes communicative meaning), and the speaking community. That is, drawing information from the cultural background and the social environment, linguistic items are arranged to form structures, and structures, in turn, are configured to accomplish communicative functions in various domains of social life (Escobar Alméciga & Evans 2014).

The aforementioned features are difficult to assimilate into our EFL context because quotidian social contact with communities of English speakers which might be used to develop them is scarce. As such, modeling the socially established conventions and language structures proves necessary in order to assimilate the rules of language use without which the rules of grammar are useless (Hymes, 1971).

In this regard, corpus linguistics offers its greatest attributes to those studies whose main concern is to "demonstrate how speakers and writers use language to achieve various communicative goals" (Meyer, 2002, p. 5). Through a systematic modeling of naturally occurring interaction samples, the arrangement of linguistic items, the function they achieve, and the reoccurrence patterns they exhibit, it represents an asset to the understandings of the structures of conversation (Granger, 1998). "Corpus linguists are very skeptical of highly abstract and decontextualized discussions of language promoted by generative grammarians largely because such discussions are too far removed from actual language usage" (Meyer, 2002, p.3).

As an example of the use of corpora with the specific purpose of inquiring about language behavior, Véliz (2008) explores the linguistic structures formed around the word "any" and the communicative functions they accomplish seeking a greater familiarity with word's most prominent usages in naturally occurring interactions. The following five were found as its most commonly used linguistic patterns in conversations: (1) this test is like any other test (2) If there are any questions (3)It will not make any difference (4) You can do it any way you want (5) I see it and it doesn't make any sense to me. In his study, Véliz identifies a gap between the ways in which textbooks and classroom practices represent the sociolinguistic use of "any" and what people really use it for. He concludes that the most important structures where the word "any" is used as well as their social significance are, at best, oversimplified, and ignored, at worst, in English instruction. He does not limit his discussion to this particular pattern, rather he elaborates on erroneous perceptions that some teachers and textbooks hold about the many day-to-day sociolinguistic patterns of language use.

Relying on corpus linguistics as well, King (2007) challenges the authenticity of activities offered by English textbooks. His study examines the impact that the lack of authenticity has on the development of communicative competence in foreign language. He explains that in Chile there is a movement to strengthen the teaching of English in order for people to have access to the current globalized work environment; however, he indicates that the texts and materials used for teaching English lack authentic language patterns of spontaneous interactions. For this reason, he sought, more than anything else, to determine the degree of similarity between the oral discourses presented by textbooks and the natural oral discourse in real communicative contexts by native speakers of English.

Similarly, Ahmadian, Yazdani, and Darabi (2011) performed a corpus study to assess semantic knowledge. Their study began from the premise that some words occur only in certain environments and establish semantic relationships with only certain other words, for example "cause" which is associated with negative events and generates a negative connotation (e.g. "cause of death," "cause problems"). This is determined by the statistical frequency and co-occurrence of these lexical-semantic relationships in conversation. Thus, "particular words tend to occur in the company of other words and [the] fluent use of a language depends on learning to use these word groups" (Kennedy, 2003, p.467).

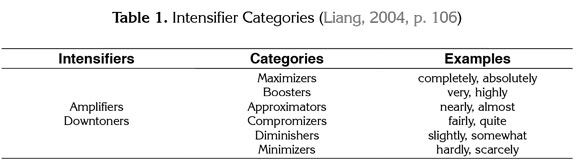

Specifically regarding expressing and modifying degree, Kennedy (2003) carries out a study which characterizes intensifiers in two subgroups: maximizers and boosters. In the group of maximizers, he presents words which convey maximum intensity like obsoletely, completely, entirely, fully, and so on; and boosters meaning less than the maximum intensity but enhance degree nonetheless like, for example, very unclear, really annoyed, and particularly helpful, among others. He also typifies downtoners like rather, a bit, somewhat, and so on. The research describes the frequency in which particular combination patterns appear, describing not only the functions they come to fulfill, but also their positive and negative connotations and the level of strength they denote. Likewise, Liang (2004) reports on the use of intensifiers in the corpus of Chinese EFL learners' spoken English comparing it to the speaking patterns displayed in the corpus of native speakers of English. He concludes that the overuse of some and the underuse of other intensifiers suggest a low understanding of the social behavior of such linguistic items and that learners overused the word very in instances in which maximizers and compromizers were more common in native speakers' speech. To such end, he used the following categorization Table 1:

In a broader sense, Altenberg (1991) also contributes with an accessible specified corpus for collocation-related studies and reports on an investigation on reoccurring collections associated to intensifiers: amplifiers and downtoners. All the aforesaid studies suggest a need for modeling and acquiring the collocations which modify degree as holistic units.

Accordingly, the study of linguistic corpora can be of use to foreign language teachers and could potentially mitigate the lack of contact, of both students and teachers, with the target language in its native use. The statistical and descriptive analysis of frequency and co-occurrence of language patterns in genuine samples raise awareness about and explain language trends according to their common social use and continual development (Recski, 2006).

Methodology

This study integrates quantitative and qualitative approaches to data analysis and it is guided by corpus linguistics principles. According to the framework provided by Biber, Conrad, and Reppen (1998), corpus-based studies have four main characteristics:

- it is empirical, analyzing the actual patterns of language use in natural texts; it utilizes [a] large and principled collection of natural texts, known as "corpus", as the basis for the analysis; it makes extensive use of computers for analysis, using both automatic and interactive techniques; [and lastly,] it depends on both quantitative and qualitative analytical techniques. (p. 4)

As a way to assess the communicative potential the students attained through their participation in an undergraduate program, the EFL university students from the course titled 'English level six' were selected as participants in this project. As this represents the highest general English course offered, it was expected to reflect the six-semester-long academic trajectory and the end-result of the EFL students' learning process as far as their involvement in English language teaching courses by levels. Most of these EFL students were in the sixth semester of a ten-semester teaching credential program and came from a low socioeconomic strata. Although they all belonged to the same English level course, they exhibited a diverse range of proficiency in their performance and many struggled to communicate in English.

For the collection of the EFL students' spoken samples, the group of participants was broken down into smaller groups (three to five) and situated in different conference rooms at the campus which created enclosed comfortable and friendly environments different from their regular classroom setting. Subsequently, ten topics of conversation were proposed which were discussed simultaneously in the small-group conversations. This yielded a fifty-hour recording of their spoken production. All the sessions were audio and video recorded, and transcribed. The resulting corpus contained 112,992 words and was uploaded onto a text processing environment as the English as a Foreign Language Corpus (EFLLC).

"For […] constructions that occur frequently, even a relatively small corpora can yield reliable and valid information" (Meyer, 2002, p.15). As such, the EFLLC corpus allowed a detailed analysis and characterization of the EFL students' language configurations around intensifiers by first identifying frequency patterns of linguistic items associated with the sematic theme of degree. Then, an additional quantitative examination on the overuse and underuse of such items was completed. A qualitative analysis followed where concordances on the most frequent items associated with the semantic theme of degree were constructed for an in-context examination of the particular linguistic arrangements in the EFL learners' corpus and, then, compared to the linguistic arrangements displayed in the native speakers' corpus (COCA)2. The calculations on frequency and use as well as the creation of concordances were carried out using a sophisticated software called Wmatrix designed by Rayson (2009).3. For this particular project the process unfolded in eight main steps.

- Informing the population of the project and selecting the participants from the course 'English Six.' Student involvement in the project was then based on each student's willingness to participate.

- Dividing the group of fourteen participants into smaller groups of three and four students and arranging the environments where the conversations were to take place.

- Audio and video recording every conversation, transcribing the recordings, editing them, and uploading them onto the Wmatrix language processing environment where these texts originally took the form of the (EFLLC).

- Statistically analyzing the students' linguistic corpus to identify the most frequently used items (observed frequency, relative frequency, overuse, and underuse) using the Wmatrix software for calculation.

- From the statistical findings, selecting particular linguistic items to create concordances to examine and describe the way they were being used.

- Identifying a corpus of native English speakers big enough to offer the needed linguistic range to validate patterns of language usage and a user-friendly interface that would enable multidimensional inquiries about English linguistic behavior (The Corpus of Contemporary American English, [COCA] (Davis, 2008) 4

- Comparing the qualitative findings from the study of the concordances generated by the Wmatrix on the contextualized use of particular items and the concordance of COCA to identify salient linguistic arrangements, communicative functions, the similarities and differences between them, and their communicative potential.

- Analyzing the two corpora to identify whether students' use of linguistic resources could potentially generate ambiguity and/or communication breakdowns as well as to describe the sociolinguistic configurations of EFL learners' utterances and their scope of possibilities.

Analysis, Findings, and Discussion on the EFL Learners' Corpus

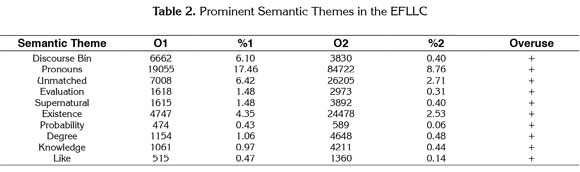

"Studies of EFL learners' use of intensifiers can be of significant value to the understanding of the learners' interlanguage development" (Liang, 2004, p. 106). Being able to express emphasis and magnify degrees and levels of description of the object about which one may be speaking is a sociolinguistic function that takes many forms demanding, at the very least, a vast scope of sociolinguistic assets to successfully assemble comprehensible and culturally appropriate utterances. With that in mind, Table 2 below displays an initial quantitative analysis where the first column outlines word-concentrations of similar meaning grouped in semantic themes. Then, O1 is observed frequency in the (EFLLC): the actual number of times words associated with a particular semantic theme appeared in the learners' corpus. O2 is observed frequency in the American Corpus (2008): the actual number of times words associated with a particular semantic theme appeared in the native speakers' corpus. %1 and %2 values show relative frequencies in both texts: the number of times that words associated with a particular semantic theme appeared in each corpus divided by the total amount of words of their corresponding corpus. Finally the + sign indicates their overuse in O1 relative to O2 (Rayson, 2009).

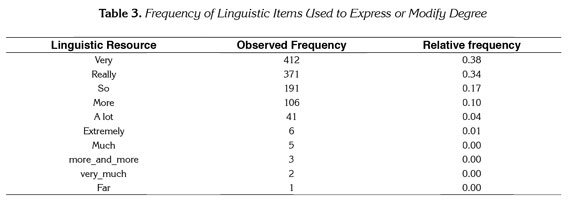

Once the linguistic repertoire evidenced in the EFLLC was broken down into semantic themes, they were organized in terms of their incidence in the learners' spoken production. Table 2 below, displays the ten most significant themes by frequency showing a tendency for their overuse relative to the incidence of the semantic themes exhibited in the corpus of native speakers. Swayed by such an observation, an individual exploration on the linguistic configurations of each semantic theme was conducted. However, this analysis here focuses exclusively on the discussion of the semantic theme associated with the pragmatics of expressing and modifying degree e.g. being able to fundamentally amplify the impact of an adjective, verb, or adverb by only adding a common degree intensifier as in 'she did very well on the test' or configuring a more cultural expression to achieve the same effect such as 'she passed the test with flying colors,' as well as the scope of the communicative potential, possibilities, and limitations that such discursive arrangements pose. The linguistic items most commonly employed in the EFL Learners' Corpus (EFLLC) to meet such ends are presented in Table 3 below where the first column indicates the linguistic item; the second column, the actual number of times that a particular word is experienced in the EFLLC, and the third, the actual number of times the words appeared in the EFLLC divided by the total-word amount employed in the same corpus.

Based on the categorization discussed by Liang (2004), we can say that the linguistic items used by the EFL learners' to express or modify degree are inherent in the category of amplifiers, more specifically, the subcategory of degree boosters within. Maximizers, on the other hand, were underused or nonexistent entirely. As far as downtoners, none of its four subcategories was significantly represented in the students' spoken production. Both, the exclusive use of degree boosters rather than a more diversified range of intensifiers, as well as the high frequency of the words very, really, so, more, and a lot correspondingly indicated a limited scope of linguistic resources and/ or the lack of knowledge to put them in use to convey more comprehensive connotations of intensities and degrees. The unfolding grasp of the EFL learners' use of degree boosters is better complemented by an analysis of concordances around these linguistic items in terms of the ways in which the language is being configured to, then, comparing them to the linguistic configurations used to achieve the same or similar functions in the COCA corpus.

In the case of our EFL learners, the functions to convey degree were predominantly attained to understandable and elementary extents mainly through the use of the words 'very' and 'really,' as shown in Table 3 below, e.g. 'is very important, is very expensive, is very difficult, they really appreciate, is really stupid, they put me really upset' (EFLLC), failing to provide denotative specificities about levels and degrees as well as failing to incorporate socially established conventions and thus falling short of accurately depicting particular accounts. Less frequently, the learners ventured out to employ other resources as in the transcription below; for example, where the EFL learner uses 'so' to magnify the impact of the adjective 'ridiculous.'

- Is so ridiculous but is so funny because in the Calera town nobody knows the relationship between the … this girl and the priest (EFLLC)

In the first occurrence of 'so,' and at an initial stage of analysis, the speaker figuratively boosts the degree of ridicule of the situation at hand by adding 'so' to 'ridiculous.' Such a structure presents a high frequency occurrence in the spoken and fictional genre, but shows a very scarce incidence in any other genre in the COCA corpus. However, such a configuration proves incomplete if the intention of the speaker is to provide a referent that would resemble the degree being enhanced. That is to say, this expression fails to convey an approximation as to how ridiculous the situation really was. The speaker could have resorted to more compound linguistic structures to enhance his/her explicit elaboration of the description to a level of complexity that would offer a referent after which a more detailed idea of the degree could have been constructed as in 'it's so ridiculous that we don't even know what to say about it' (COCA). However, still an abstract notion, this configuration categorizes the situation as ridiculous and describes what such ridicule generates by drawing a mental image of the circumstances. Despite the endless possibilities and linguistic items the speaker could have resorted to but did not, s/ he positively manages to combine two views in opposition e.g. 'is so ridiculous but is so funny,' offering an explanation for the funny part of the utterance but neglecting a description of the degree of ridicule which could have been expressed with a structure like 'it's so ridiculous that we don't even know what to say about it but so funny because…'

Patterns of language use and linguistic resources undergo variations from context to context and genre to genre dictated by the sociocultural principles governing language use. On the topic of naturally occurring conversations, the word 'damned,' for instance, is socially acceptable in some situations but would definitely prove inappropriate in others. That is, whereas a spontaneous conversation between friends of particular characteristics may exhibit a regular use of the word 'damned,' an EFL learner must come to the realization that the same linguistic structure would most likely be unfit for a formal classroom interaction or a conference if the topic of conversation does not openly call for it. Additionally, 'damned' does not display a high frequency occurrence in the academic or the news genre but it shows an extremely high frequency in fiction and an average incidence in speaking in COCA. In the excerpt below, for example, the learner uses the word 'damned' in an informal yet somewhat academic setting which, at the outset, signals a contextual incongruity for such a word choice. However, it is worth looking past such mismatch onto the subsequent student's linguistic construction to boost degree.

- So is, he is so damned because Jesus come the world to, to share all aspects of our life, so is damned that people can´t get married. I think that. (EFLLC)

In most cases, the word combination above is commonly found in COCA in adverbial expressions where 'so' modifies a subsequent adverb after 'damned' as in 'that sounds so damned familiar.' In such cases, both words 'so damned' serve as degree boosters for the word 'familiar.' The second and third most common forms in which 'damned' appears in naturally occurring interactions of native speakers (COCA) do not include the use of 'so' to boost degree and in those cases 'damned' serves as an adjective as in 'he would keep the damned dog,' and as a verb as in 'perhaps what damned Amanda most was her old soccer nickname she used.' The function of modifying degree is not being fulfilled in either structure.

Moreover, not all words and expressions regarding degree can be applied indistinctly to every situation; they possess particular features which provide the specific denotations that modify the degree of something and to erroneously generalize them may result in an altering of the actual intended meaning or natural flow of a given expression as in the case of 'such/so' in the excerpt below:

- I live in… in Cali and, on a small region. And, for example, if you have long hair, you are a satanic person. They are so freak. And, yeah. Ha, for example, I used to, ha, have long hair. They, no! I was a satanic and gay. (EFLLC)

In an effort to describe a situation in which people with certain characteristics are singled out as a deviation from the social norm (freaks), the learner makes an attempt to magnify the degree of such description but instead of using 'such a freak' s/he uses 'so' whose combination is most commonly found in expressions like 'so freaked out,' as in 'When I left Alaska, I was so freaked out about leaving rural life that I hid out in …' (COCA). In the latter case, the expression conveys a completely different connotation of fear and apprehension rather than a depiction of a social phenomenon where someone is marginalized as a result of his/her differences creating ambiguity about the speaker`s intended meaning.

Likewise, there are combinations that may be understandable but awkward in the sociolinguistic context of use as their pragmatics may not be common among competent or native speakers of English thus falling short in capturing denotations as in 'yeah so that was very annoying, that she dranks a lot' (EFLLC). Looking at this example from the literal meaning perspective, the sentence makes perfect sense boosting the amount of alcohol being consumed and the feelings that such an action brought about. However, other features and intended meanings emerge when we enlarge the context:

- Yeah… eha… well and started to be eight, nine, ten, eleven… twelve! And she didn't arrive. So well, I go to my home and at the other day, she come me with a very very bad XXXXX and it turns that she stayed with her friend drinking so much all night she… she lost her cellphone, her ID, all the stuff, personal stuff and she lost… ah… well that was one of the […] yeah so that was very annoying, that she drunks a lot. (EFLLC)

We did not enlarge the transcription enough to know whom the speaker was referring to or the relationship they shared, but what we can see is that the speaker is telling a story from the past where a girl had so much to drink that it caused her to miss their appointment and to lose her personal belongings. Going beyond the sentence level of interpretation to considering the contextualized utterance, the speaker created a point of reference where the amount of drinking was being proportionally measured by the effects it caused (losing everything and not showing up). Conveying how annoying it was that she drank the amount she did would have been more accurately depicted and more commonly expressed by using 'so much' rather than 'a lot' e.g. 'yeah so that was very annoying, that she drank so much,' 'so much' referring back to its effects: so much as to lose everything and never show up. As in the structure in the following example from COCA, 'I find it ironic that we spend so much time and effort to create airport terminals,' this lack of command of degree boosters casts doubt on other expressions of similar configurations like 'you don't earn so much' (EFLLC). The latter sentence creates ambiguity in the sense that it could mean that the person does not earn enough money to afford a particular item or service, or that the speaker could have potentially meant that someone did not earn very much money in general terms.

Another form in which degree is often magnified is in a progressive escalation which requires intricate word and tense combinations and is a salient example of how semantics and pragmatics interact to create meaning. The sample below displays a few shortcomings attempting such a function:

- I never went. And, and I, I start to, to to be so upset about that and I save a lot of money all through all the, that eleven years, and I, uhm and I have, and now I have my own business. (EFLLC)

To begin with, the word 'start' signals the intended progression of an event in the learner's utterance. Bearing in mind that the student is narrating a past experience, the first shortcoming is grammatical as it should have been in the past form (started). However, looking past the grammatical aspects and considering that this is an action in progress, the choice of the word 'be' most closely resembles a more fixed state, condition, or situation which does not change making the sentence awkward. Thus, a better word choice to express progression, of course, would have been the word 'get' or 'feel' as in I started to get or I started to feel (so upset). Despite the fact that using 'be,' 'get,' or 'feel' does not constitute a grammatical error, it does represent the pragmatic skill that allows the learner to make the best choice among his/her linguistic repertoire to effectively and accurately fulfill a communicative function of this nature.

Similarly, in EFLLC, the participants usually chose the word 'more' to simply compare two things in terms of degree, as in the first data sample below. In a few other cases, however, they found a way to articulate the notion of progression that we have been discussing through the expression 'more and more' as in the second example below:

- I consider that religion is like uhm like… like the process of doing certain things in order to ha, inr order to gain something or to obtain something from God, and I don't believe that. I, I, I, believe more in something like a relationship with God. (EFLLC)

And, I learned how to correct and when, when I was correcting that, all that, eh, tests, I was learning more about the English because I had to, to ask, ah, once, twice , three times , ah , about what was the , the , the right answer . And I, eh, I th-, I think that I learned mo-, every, every, every Friday I learned more and more. (EFLLC)

In the first example, the speaker uses 'more' first to communicate disagreement about a religious stance and second to highlight his/her own spiritual claim in an exercise of comparison. In the second example, the student achieves a progressive effect in his/her account describing how his/her learning was gradually increasing every Friday and simultaneously boosting the level of learning taking place.

Other sociolinguistic patterns demand an even more complex pragmatic composition encompassing the functions like magnifying degree, expressing progression, and establishing proportional relations of cause and effect. Plus, they prove highly common in the native American corpus as in 'the more I became aware of it, the stronger I felt' (COCA). Such structures, however, become particularly challenging for the EFL learners as shown below:

- Well, that's the word, but, because that's what she does. And she's the kind of mom that, that considers that ah, as much you eat, as better your health is going to be. (EFLLC)

'As much you eat (sic)' in the second line of the excerpt signals a relation of contrast between the two clauses potentially misleading the semantic association with structures like 'as much as I admire Jimmy Carter, I'm a bit disappointed' (COCA), which depict a level of disagreement between the two ideas and differ greatly from the connotation intended in this conversation. The second clause suggests that the leaner misused the collocation 'as much' in the place of 'the more' in an attempt to convey a directly proportional association as in 'she is the kind of mom that considers that the more you eat, the better your health is going to be.' The incidence of this same syntactical structure depicting inversely proportional associations in progress as in 'the more he wrote the less he dreamed' is equally representative in COCA. Even though there does not seem to be major syntactical mistakes in the sentence, this configuration of language diverges from the common use of English in natural settings generating ambiguity in semantic associations and representations.

In a similar manner, semantic representations may be also altered by changing the syntactic order of the sentence resulting in structures that could potentially convey unintended meanings as in 'Before women used a lot of dress' (EFLLC). At a quick glance, 'a lot' in this case serves as a quantifier projecting the idea that women used many dresses as in 'a lot of Americans,' 'there are a lot of band numbers, a lot of baggage,' etc. However, adding a little more context and taking into account that "part of the process of determining what speakers mean (as opposed to what their words mean) involves assigning sense to those words" (Thomas, 1995, p. 6) (i.e. semantics versus pragmatics correspondingly) the contrast being made between the use of dresses and jeans makes a clear reference to a frequency related notion of how often women wore dresses in the past as opposed to how often they do so now.

- EA10M: It depends on the age AS3F: Yeah for example QL20F: But it depends AS3F: Before women used a lot of dress maybe QL20F: When you are old yeah AS3F: And now no. Now they use jeans, pants QL20F: But… but when you are old you can't use eee jeans all the time (EFLLC)

The idea above would have been more effectively achieved by changing the order of 'a lot' in the syntactical organization of the sentence (before, women used dresses a lot) as in the following examples from the COCA corpus which refer to frequency: 'My brother has moved a lot,' 'I travel a lot,' 'I smoked a lot,' 'I ask a lot,' etc. (COCA).

Even the smallest structures with meaning can create ambiguity or have an impact on communication like misusing adverbs and adjectives interchangeably. The word 'extremely,' for example, is often used in the place of 'extreme' in the EFLLC, not necessarily interfering with the exchange of meaning in interaction but creating awkwardness that many times inhibit the normal flow of communication.

- Mmm ok, is very confuse and difficult to, to talk about that. Ok, my home, my family, eh lived a bad situation and for this reason all my family… eh needed to travel to…to Bogota. Yeah? Because, eh, we, we don't we can't live ah in… in… in… in my town, and ok. It was in… in… in twenty, eh o seven. Yeah? This, this that- , eh a that was my, my first year here in Bogota, and all the time I want to, I wanted to to, to know Bogota, and, Ok. Was a v- , a extremely situation and ok, yeah. (EFLLC)

The word extremely is an adverb and most frequently acts along with an adjective to boost the degree of the description of a verb as in 'making it extremely difficult,' 'population comprises an extremely diverse and heterogeneous group,' or just amplifying an adjective as in 'extremely radical,' 'extremely positive,' 'extremely problematic.' Less often can we find it boosting the degree of another adverb as in 'do it all extremely quickly,' 'he is going to do extremely well financially,' 'extremely environmentally friendly' (COCA). In the case of the EFL learners, 'extremely' was most commonly associated with an adjective as in 'Ah, my teacher, Camilo […] was extremely strict' (EFLLC) and fairly frequently confused with other inflections of the word.

Among the endless forms that our EFL learners' attempts employed to boost degree, one was that they also exhibited an effort to step away from the sociolinguistic configurations provided by their Colombian Spanish background, i.e. employing structures whose meaning representations diverged greatly from their own. For example, using the word 'far' to boost degree:

I have to separate into Geometry and Math. It's far better. (EFLLC)

Literally, the word formation would not make much sense to a Spanish speaker as in Spanish the adjective 'better' is usually combined with 'much' rather than 'far' which, in turn, is typically associated with a notion of distance.

In short, understanding that all languages are articulated by completely different syntactic systems and sociocultural knowledge (which create unique representations that cannot be directly substituted or literately translated) is every bit of what acquiring a subsequent language means. It involves a socio-cognitive process that not only requires the learning of vocabulary and structures, but most importantly, it entails the rediscovery of one's own reality and an appreciation of the world through a different set of cultural lenses.

Conclusions and implications

The EFLLC unveiled patterns of lexical incidence inherent in ten main semantic themes, namely, discourse bin, pronouns, unmatched to any semantic tag, evaluation, supernatural, existence, probability, degree, and knowledge. On the resultant topic of intensifiers used to express or modify degree which was the focus of this paper, the use of amplifiers was evidenced, while downtoners were not employed by the learners. Similarly, within the broader category of amplifiers, degree boosters like very, really, so, more, a lot, and the like disclosed high incidence, while maximizers showed no incidence at all. Such restricted linguistic spectrum evidenced in the learners' corpus implies a lack of linguistic repertoire, or the sociolinguistic knowledge to use a wider range of language configurations to express or modify degree.

As far as the degree boosters employed by the learners, the descriptive analysis leads us to conclude that, in many instances, degree boosters like 'so', 'such', and 'more' were erroneously used indistinctively in places where the other was more appropriate. Other cases supported the stance on viewing word combinations and language configurations as a unit as the learners experienced difficulty uttering complete expressions as in 'so damned + adjective or adverb' to magnify degree or used the wrong combination, the wrong from, or the wrong order of words. In other words, whereas in many instances, degree boosters were successfully used at various denotative levels, in others they failed to faithfully resemble sociolinguistic arrangements common to native speakers.

Predominantly, the EFL learners limited themselves to language configurations which resembled their own sociocultural knowledge from their linguistic background as well as to the simple structures that do not require complex organizations of parts of speech or the embracing of the target language's sociocultural idiosyncrasies. Expressions that exhibited arrangements particular to the target language were hardly evidenced and, thus, specificities regarding levels and degrees did not adequately bear the full extent of the sociocultural dimensions and representations in their intended descriptions.

Generally, the lack of the sociocultural knowledge embedded in the target language causes faulty word choice which reflects inaccurate and unintended meanings. A limited linguistic repertoire and the lack of sociocultural competence needed to configure such a repertoire force the EFL students to overuse some linguistic items at best and erroneously employ them in situations where the word does not fully represent or completely misrepresents, at worst, the intended meanings.

Even though the students revealed a vast linguistic repertoire in EFL, their sociolinguistic knowledge appears insufficient to read contextual information in order to distinguish the type of linguistic resources, forms, and genres to draw upon for particular contexts and in given genres. Word choice and the configuration of language are contingent to the specificities of the context: There are words that can be used in only a few specific situations as well as some linguistic items that can establish associations only with certain others for specific purposes and in particular settings and situations.

Degree boosters create referents of diverse natures establishing various types of relationships with each sentence component: Sometimes they depict direct proportionality, inverse proportionality, cause and effect, and so on. Losing track of such referents altogether can denote the wrong relationship or result in a half-finished idea. Similarly, semantic operations can be misrepresented and lose meaning as a result of the wrong word choice, awkward or erroneous syntactical organization, the usage of the wrong part of speech, the pairing of the wrong words, and/or a combination of words creating ambiguity.

Even so, comprehending the formal and prescriptive rules of language structure offered by EFL textbooks and EFL materials is an important aspect in order to be able to function in proper settings like academic performance, communication in the professional and work environment, and accurately addressing people according to their social, hierarchical organization. It is also essential to understand that limiting the EFL students to such a particular genre alone falls short in forming competent speakers who could function well in all other social settings.

The use of corpus in the EFL classroom represents an alternative resource which, on the one hand, offers a vast inventory of language samples collected from natural social use, providing information on language behavior and the opportunity for language modeling discriminated according to the genre. On the other hand, there currently exist numerous types of interfaces on the internet hosting a wide variety of corpora and genres offering endless features for language analysis and language learning. COCA, for instance, allows the input of text to characterize linguistic patterns analyzing word frequency, aiding the creation of word sketches, running synonym and antonym comparison in relation to other words and/or collocations, and typifying differences regarding meaning and use between words and collocations (as well as language variations exerted by sociopolitical forces).

In short, the social principles governing language use do not come in a user's manual and cannot be taught through traditional classroom instruction; rather, they come as a result of the active partaking in communication where such conventions are not only learned but are also created, appropriated, and transformed. In the case of EFL contexts where the original source of these sociolinguistics principles is distant, approaches and strategies aiming at the creation of communicative environments and the modeling and subsequent appropriation of such patterns must be designed and implemented. Thus, one sees the importance of understanding corpus as a resource that could potentially foster linguistic development by making up for some of the above said shortcoming.

Comentarios

2 The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) contains more than 450 million words of text and is equally divided among spoken, fiction, popular magazines, newspapers, and academic texts. The interface allows you to conduct searches at a Word, parts of speech, collocation, and sentence levels it also provides genre, domain, and contextual information (Davies, 2008).

3 This language processing environment will be referred to as Wmatrix

4 Davis (2008), the compiler, of the COCA corpus, explicitly expresses his desire for this corpus to be cited as COCA rather than as Davis (2008) highlighting the fact that he is not the author rather the compiler of such linguistic inventory.

References

Ahmadian, M., Yazdani, H., & Darabi, A. (2011). Assessing English learners' knowledge of semantic prosody through a corpus-driven design of semantic prosody test. English Language Teaching, 4(4), 288- 298. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/913379285?accountid=41311 [ Links ]

Altenberg, B. (1991). Amplifier collocations in spoken English. In S. Johansson & A. B. Stentsrom (Eds.), English computer corpora: Selected papers and research guide (pp. 127-147). Berlin: Mouton. [ Links ]

Aston, G. (2000). Corpora and language teaching. In L. Burnard & T. McEnery (Eds.), Rethinking language pedagogy from a corpus perspective: Papers from the third international conference on teaching and language corpora (pp. 7-17). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Bauman R., & Sherzer, J. (1975). The ethnography of speaking. Annual Reviews, Department of Anthropology University of Texas, Austin, Texas. [ Links ]

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Reppen, R. (1998). Corpus linguistics: Investigating language structure and use. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. [ Links ]

Canale, M. (1983). From communicative competence to communicative language pedagogy. In J. C. Richards & R. W. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and communication (pp. 2-27). Harlow, England: Longman. [ Links ]

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied linguistics, 1(1), 1-47. [ Links ]

Davies, M. (2008). The Corpus of Contemporary American English: 450 million words, 1990-present. Available online at http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/ [ Links ]

Escobar Alméciga, W. Y., & Evans, R. (2014). Mentor texts and the coding of academic writing structures: A functional approach. HOW, A Colombian Journal for Teachers of English, 21(2), 94-111. [ Links ]

Escobar, W., & Gómez, J. (2010). Silenced fighters: Identity, language and thought of the Nasa people in bilingual contexts of Colombia. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 12(1), 125- 140. [ Links ]

Granger, S. (1998). Learner English on computer. London and New York: Addison Wesley Longman. [ Links ]

Griffiths, P. (2006). An introduction to English semantics and pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Hymes, D. H. (1971). On communicative competence. In J. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics (pp. 269-294). London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Kasper, G. (2001). Four perspectives on L2 pragmatic development. Applied Linguistics, 22(4), 502-530. [ Links ]

Kennedy, G. (2003). Amplifier collocations in the British National Corpus: Implications for English language teaching. Tesol Quarterly, 37(3), 467-487. [ Links ]

King, P. (2007). Estudio multidimensional de la oralidad a partir de los textos escolares para la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera. Revista Signos, 101- 126. [ Links ]

Liang, M. (2004). A corpus-based study of intensifiers in Chinese EFL learners' oral production. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching (AJELT), 14, 105- 118. [ Links ]

McEnery, T., & Wilson, A. (1996). Corpus linguistics: An introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Meyer, C. F. (2002). English corpus linguistics: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia. MEN (2004). Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo. Retrieved January 10, 2010 from: http://www.colombiaaprende.edu.co/html/productos/1685/article-158720.html and from http://www.colombiaaprende.edu.co/html/docentes/1596/article-82607.html#h2_4 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia MEN. (2006a). Educación: visión 2019: propuesta para discusión. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/cvn [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia. MEN (2006b). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Formar en Lenguas extranjeras: ¡el reto! Lo que necesitamos saber y saber hacer. Bogotá: Imprenta Nacional. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia MEN. (2007). Plan Nacional de Desarrollo Educativo. Retrieved from: http://planeacion.univalle.edu.co/a_gestioninformacion/plandeaccion2008-2011/PND_2010_Educacin%20pdf1.pdf [ Links ]

Nguyen, M. T. T. (2011). Learning to communicate in a globalized world: To what extent do school textbooks facilitate the development of intercultural pragmatic competence? RELC Journal, 42(1), 17-30. [ Links ]

Parodi, G. (2005). Discurso especializado y lingüística de corpus: Hacia el desarrollo de una competencia psicolingüística. Boletín de Lingüística, 61-88. [ Links ]

Portner, P. (2006). Meaning: An introduction to language and linguistics. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Pütz, M., & Neff-van Aertselaer, J. N. (2008). Developing contrastive pragmatics interlanguage and cross-cultural perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Rayson, P. (2009). Wmatrix: A web-based corpus processing environment. Computing Department, Lancaster University. http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/wmatrix/ [ Links ]

Recski, L. J. (2006). Corpus linguistics at the service of English teachers. Literatura y Lingüística, 303-324. [ Links ]

Saville-Troike, M. (2003). Basic terms, concepts, and issues. In The ethnography of communication: An introduction (3rd ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Pub. [ Links ]

Schmidt, R. (1983). Interaction, acculturation, and the acquisition of communicative competence. In N. Wolfson & E. Judd (Eds.), Sociolinguistics and second language acquisition (pp. 137-174). Rowley, MA: New Bury House [ Links ]

Schumann, J. H. (1978). The pidgination process: A model for second language acquisition. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. [ Links ]

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Spolsky, B. (1998). Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Thomas, J. (1995). Meaning in interaction: An introduction to pragmatics. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Véliz, M. (2008). La lingüística de corpus y la enseñanza del Inglés (como lengua extranjera): ¿Un matrimonio forzado? Literatura y Lingüística, 251-263. [ Links ]

Viana, V. (2006). Modals in Brazilian advanced EFL learners' compositions: A corpus-based investigation. Profile: Issues in Teachers´ Professional Development, 7, 77-86. [ Links ]