Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.14 no.1 Bogotá Jan./Mar. 2015

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy14-1.rboc

Relation between Organizational Commitment and Professional Commitment: an Exploratory Study Conducted with Teachers*

Relación entre el compromiso organizacional y el compromiso profesional: un estudio exploratorio realizado con docentes de educación superior pública

Dora de Jesús Gúerreiro Figúeira**

University of Lisbon; University of the Algarve, Portugal

José Luís Rocha Pereira do Nascimento***

University of Lisbon, Portugal

Maria Helena Rodrigues Guita de Almeida****

University of the Algarve, Portugal

*Original research article

**Master at the University of Lisbon, Instituto Superior de Ciencias Sociais e Políticas. Head of Division of Human resource services, University of the Algarve. E-mail: djfiguei@ualg.pt

***University of Lisbon, Instituto Superior de Ciencias Sociais e Políticas. E-mail: jnascimento@iscsp.ulisboa.pt

****University of the Algarve, Faculty of Economics. E-mail: halmeida@ualg.pt

Received: February 5th, 2014 | Revised: October 18th, 2014 | Accepted: October 18th, 2014

To cite this article

Guerreiro Figueira, D. J., Rocha Pereira do Nascimento, J. L., & Rodrigues Guita de Almeida, M. H. (2015). Relation between Organizational Commitment and Professional Commitments: an Exploratory Study Conducted with Teachers. Universitas Psychological, 14(1), 43-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy14-1.rboc

Abstract

The existence of several kinds of commitments in the workplace is well known. However, there are few studies that relate these different commitments or those established by deterministic models. This study explored the relationship between organizational and professional commitment in public higher education professors according to the multidimensional perspective of Meyer and Allen (1991), based on a convenience sample of 219 teachers. The proposed models were estimated through structural equation modeling methodology. Model 1 specified a relationship of direct influence of Professional Commitment on Organizational Commitment and Model 2 established the opposite relationship of direct influence of organizational commitment on professional commitment. Both models presented a good fit to the data without statistically significant differences between them. Nevertheless, the explanatory power of Model 1 was superior to Model 2, due to the fact that it includes a larger number of determinant relationships that are statistically significant. Theoretical and practical implications were discussed and new directions for future research were identified.

Keywords: organizational commitment; professional commitment; public higher education professors

Resumen

Es conocida la existencia de distintos tipos de compromiso en el puesto de trabajo. Con todo, existen pocos estudios que los relacionen o que establezcan modelos determinísticos entre sí. Este estudio exploró la relación entre el Compromiso Organizacional y el Compromiso Profesional de docentes de educación superior pública, a partir de la perspectiva multidimensional de Meyer y Allen (1991), en base a una muestra de conveniencia constituida por 219 docentes. Los modelos propuestos se estimaron a través de la modelación de ecuaciones estructurales. El Modelo 1 especificó una relación de influencia directa del Compromiso Profesional sobre el Compromiso Organizacional y el Modelo 2 una relación inversa, de influencia directa del Compromiso Organizacional sobre el Compromiso Profesional. Los dos modelos presentaron un buen ajuste a los datos sin que se haya observado diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre sí. No obstante, el Modelo 1 por integrar un mayor número de relaciones de determinación estadísticamente significativas evidenció un poder explicativo superior al del Modelo 2. Se debatieron implicaciones teóricas y prácticas y se identificaron líneas futuras de investigación.

Palabras clave: compromiso organizacional; compromiso profesional; docentes de educación superior pública

Introduction

The interest for studying Commitment is due mostly to its association with efficiency and productivity in organizations by increasing individual performance, pro-social behavior and innovation, low levels of absenteeism and turnover intent (Klein, Molloy, & Cooper, 2009; Meyer & Allen, 1997; Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002). The organization is one of the most studied outbreaks by Commitment, but the interest in the subject is not confined to the study of Organizational Commitment since it has witnessed a growing interest in commitment associated to the profession, commonly known as Professional Commitment.

Although Professional Commitment and Organizational Commitment have been the subject of several empirical studies, there are relationships that have not yet been analyzed adequately, in particular, the relationship of determination of one over the other, in absence of a consensual position on this issue (Cohen, 1999; Klein, Molloy, & Brinsfield, 2012; Meyer, Allen, & Smith, 1993; Morrow, 1983; Randall & Cote, 1991). Thus, the present study aims to identify the directionality of the relationship between Professional and Organizational Commitment, positioning itself in the study of Meyer, Allen and Smith (1993). Like the study of Meyer et al. (1993), we have chosen to use a profession with a strong specialization and high professional culture that stems from the specific nature and differentiating associated activities (Sainsaulieu, 1988), in particular, the teaching at a Portuguese State University at the State University college.

Theoretical Framework

Organizational Commitment

The Organizational Commitment began to receive greater attention from the early 60 of last century (Klein, Molloy, & Cooper, 2009). Since then it has been defined and measured in various ways, having many authors opted to formulate their own conceptualization of the construct and proposed specific measuring instruments (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001; Morrow, 1983; Reichers, 1985). At present there is no agreed definition of Organizational Commitment (Klein, Molloy, & Cooper, 2009) although multidimensional approaches, which argue that this construct is comprised of several components, have wider acceptance. It is in these that the model of Three-components of the Commitment of Meyer and Allen fits (1991, 1997), it is developed with the goal of integrating the one-dimensional dominant conceptualizations. According to Meyer and Allen (1991, 1997) Organizational Commitment is a state of mind that characterizes the relationship of specific nature between the contributor and the Organization, and has implications on its decision to continue or not in the Organization.

The nature of this relationship can be affective, normative and calculative, constituting these three types of relationship, represented by the three components of Organizational Commitment: affective, normative and calculative. In this context, employees with a strong affective Commitment remain in the organization because they want to; normative remain in the organization because of the sense of duty or of moral obligation; calculative remain in the organization because they need to (Allen & Meyer, 1996; Meyer & Allen, 1991, 1997). This is how the Organizational Commitment is considered a bond resulting from the intensity of the three components that integrate: affective, normative and calculative (Meyer & Allen, 1997; Klein, Molloy, & Cooper, 2009).

Despite the weaknesses that are identified, in particular, the high relationship between the affective and normative components and possible two-dimensional nature of calculative component (Klein et al., 2009; Meyer & Allen, 1997; Rego & Souto, 2004), the model of Three-component of Organizational Commitment has been one of the models that have featured more stable and consistent results in a plethora of empirical studies (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002) and one that best has "... withstood sampling and cultural contingencies" (Rego & Souto, 2004, p. 160).

Professional Commitment

Although professional Commitment has been the subject of a smaller number of studies compared to Organizational Commitment, it was referenced during the 50s of last century (e.g., Becker & Carper, 1956; Gouldner, 1957, 1958). Until the early 90s of last century Professional Commitment was approached essentially from a one-dimensional perspective (Cohen, 2007), having been conceived as a bond of affectionate nature towards the profession (e.g., Aranya, Pollock, & Amernic, 1981; Blau, 1985; Lachman & Aranya, 1986).

Professional Commitment is defined by Lee, Carswell and Allen (2000) as "the psychological connection between an individual and his profession, based on affective reaction of the individual towards this profession" (p. 800). As Organizational Commitment, Professional Commitment also evolved from a one-dimensional perspective for a multidimensional approach, mainly through the generalization of the profession of measures designed to study the organizational commitment. It was in this context that Meyer and colleagues (1993) expanded the model of Three-components of the Organizational Commitment of Meyer and Allen (1991) to a professional context. The results obtained from a sample of nursing students and nurses have revealed that the measurements of the three components included in the Professional Commitment - affective, calculative and normative - differed among themselves, as well as the three components - affective, calculative and normative - included in the Organizational Commitment.

These revelations could support the thesis that we were in the presence of two independent constructs (distinguished), although related to each other. Professional Commitment began to receive greater attention, particularly as a result of the rapid transformations of the economy and the world of work and its reflexes in the workers' professional pathways. According to Meyer (2009), in a context of high instability a growing importance of other forms of commitment in the workplace is expected, in addition to the Organizational Commitment. Dealing with uncertainty and with the difficulties of working life leads workers to redefine their commitment targets, causing them to look beyond the Organization and to carefully consider the nature and limits of their connection to the Organization and, in some cases, redirect their emotional energy to the profession (Cohen, 2007; Tsoumbris & Xenikou, 2010; Meyer, 2009).

Relationship between Organizational Commitment and the Professional Commitment.

Formulation of Hypotheses

Interest in the study of the relationship between Organizational and Professional Commitment is developed largely from the perspective of conflict between both constructs, as suggested in the works of Gouldner (1957, 1958). According to this author, in organizations there are two types of distinct and antagonistic contributors among themselves: cosmopolitans and locals. Cosmopolitans are oriented mainly to the profession, while locals focus on the organization. These two identities reflect an organizational tension resulting, on the one hand, the need for a loyalty to the Organization (local) and, on the other, the maintenance and development of personal skills related to their profession (cosmopolitan).

Thus, in professions of high technical requirement, with a strong formal and informal statutory identity (e.g., doctors, nurses or, from the perspective of this study, academics), proposed by Sainsaulieu (1988), the Professional Commitment will tend to outweigh Organizational Commitment (Gould-ner, 1957, 1958). This theory was restricted to the affective component of commitment (Lee, Car-swell, & Allen, 2000), based on the argument that the organizational and professional standards and values are incompatible with each other, leading to an inverse relationship between Organizational Commitment and Professional Commitment (Lee, Carswell, & Allen, 2000; Randall & Cote, 1991).

Later, this perspective of the mismatch gave way to a two-dimensional conception in the Organizational and Professional Commitment, which were understood as two independent but complementary to each other constructs that, within the Organization, facilitate the implementation of the professional expectations of the developer or may reward their professional behaviour (Chang, 1999; Lachman & Aranya, 1986; Neumann & Finaly-Neumann, 1990; Wallace, 1995). The initial prospect that these two constructs are inversely related or are completely independent was replaced by the conviction that these variables have a positive relationship (Tsoumbris & Xenikou, 2010). However, according to Lachman and Aranya (1986), none of these two approaches consider the possibility of determining a relationship between the professional and organizational commitment. There are researchers that argue that Professional Commitment is an antecedent of Organizational Commitment (e.g., Lachman & Aranya, 1986; Vandenberg & Scarpello, 1994). However, Meyer et al. (1993) despite having established the independence of the two constructs, as well as the existence of a relationship between them, did not establish unequivocally, a determination of one over the other. Then we can establish a first model in which M1: Professional Commitment is a determinant of Organizational Commitment. Also, it is established that the organizational features are a distant antecedent of the commitment in the workplace (Meyer & Allen, 1997). Thus, in organizations characterized by having a high and complex technology (e.g., hospitals and other similar health organizations, research centres and universities) it is permissible to consider the possibility of organizational characteristics that determine the organizational commitment, which will determine the professional commitment.

This possibility is also supported by studies of Aranya, Pollock, and Amernic (1981), using a sample of statutory auditors in the public sector, they found that the professional commitment increased as a function of organizational commitment, being the latter a determinant of professional commitment. Thus, one can establish a second model in which M2: Organizational Commitment is a determinant of professional Commitment. Despite the interest that organizational commitment has awakened, particularly through the completion and publication of different studies (Klein, Molloy, & Cooper, 2009), we know very little about how the various components of commitment are interrelated and how they interact to influence behavior (Meyer, 2009). As for the organizational commitment, most existing studies suggest that the affective component is positively related with the normative and not related to the calculative. The relationship between the normative component and calculative is more pronounced than the relationship between the affective and calculative, being significant in some cases (e.g., Johnson, Groff, & Taing, 2009; Meyer & Allen, 1997; Meyer, Allen, Smith, & 1993; Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002; Williams, Rayner, & Allinson, 2012).

However, there are also studies in which the relationship between the three components are significant (e.g., Nascimento, Lopes, & Salgueiro, 2008), suggesting the existence of commitment profiles, as was verified, for example, by Wasti (2005), and Tsoumbris and Xenikou (2010), as well as by Meyer and Parfyonova (2010) and Meyer, Stanley and Parfyonova (2012). In relation to Professional Commitment, several studies suggest the existence of a relationship between the three components (e.g., Chang, Chi, & Miao, 2007; Dwivedula & Bredillet, 2010; Irving, Coleman, & Cooper, 1997; Meyer et al., 1993; Snape & Redman, 2003; Tsoumbris & Xenikou, 2010). Meyer and colleagues (1993) examined the relationship between the two types of commitment, organizational and professional, from the model of Three-components, and found that the strongest relationships are not confirmed with each other, but rather among its components, included in each of the two types of commitment. On the other hand, Meyer and colleagues (1993) also verified the existence of significant correlations between components of different nature either in organizational commitment, whether professional, or between the two. The only exception found refers to the relationship between the affective component of organizational commitment and calculative component, both in organizational commitment as the professional. These results were also confirmed in subsequent studies (e.g., Chang, Chi, & Miao, 2007; Dwivedula & Bredillet, 2010; Tsoumbris & Xenikou, 2010).

Thus, although the two models proposed are substantiated, the theoretical framework established suggests that model 1 is the most suitable (Chang, Chi, & Miao, 2007; Cohen, 2007; Dwivedula & Bredillet, 2010; Lee, Carswell, & Allen, 2000; Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001; Meyer et al., 1993; Vandenberg & Scarpello, 1994). Finally, the nature and characteristics of the population used and, in particular, the strong professional culture that characterizes this type of occupations (Sain-saulieu, 1988), supports the following hypothesis: The level of intensity of the components of professional Commitment is greater than those of the Organizational Commitment.

Methodology

Instruments

Data were collected during the months of May and June 2012 through an electronic questionnaire, being the answer given in a Likert type scale of 7 points in that (1) corresponds to "totally disagree" and (7) to "totally agree". A relative of sociodemo-graphic variables of the professional participants was also included. To measure the components of Organizational Commitment we used the scale proposed by Meyer and Allen (1997), adapted to the Portuguese context of Nascimento, Lopes and Salgueiro (2008). It consists of a total of 19 items, from which 6 items were related to the affective component (3 of them reversed), 6 to the normative (1 of which reversed), and 7 to the calculative. The Cronbach's alpha coefficients values found by Nascimento and colleagues (2008) were of 0,91 for the affective range, 0,84 to normative and 0,79 for the calculative. The professional commitment components were measured through the scale proposed by Meyer and colleagues (1993) 6 items on each scale (3 items reversed on affective component 1 on normative, and 1 on calculative), for a total of 18. Cronbach's alpha coefficients found by Meyer and colleagues (1993) were from 0,87 (beginning of year) and 0,85 (end of year) for the affective component, 0,73 and 0,77 (respectively at the beginning and at the end of the year) for the normative, and 0,79 and 0,83 (also respectively at the beginning and at the end of the year) for the calculative.

The Sample

A convenience sample consisting of 219 teachers of a national public University was used. From this sample, 54.8% are female and 48.2% male. The average age is 45.8 years, varying between 23 and 63 years. Most participants are professors of career (61.7%), and in total, more than 80% exercise functions in a full-time regime (68.5% with exclusivity and 14.2% without exclusivity). Only a small percentage teaches part-time (17.3%). Seniority in the profession is 16.9 years and at the institution is 14.8 years. It should be noted that 58.9% of the participants belong to the subsystem of polytechnic education, while 41.1% of the participants belong to the University.

Options for the Treatment and Analysis of Data

In the evaluation of the adjustment of structural models, the following measures were used: Chi-square (%2), Chi-square value by the number of degrees of freedom (%2/df < 3.0), Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI ≥ 0,9), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA≤ 0,08), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR≤ 0,09), Comparative Fit Index (CFI≥ 0,92). As a measure of comparison of models we used the Akaike Information Criterion AIC, being the model more adjusted to produce the smallest value of the model AIC (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010; Salgueiro, 2008). It was also the coefficient of determination (R2 ≥ 0,4) to estimate the percentage of the variance of the dependent variables, explained by the independent variables (Hair et al., 2010; Maroco, 2010).

Presentation of the Results

Descriptive Statistics

We started by analysing the descriptive statistics of the latent variables (Table 1). It was found that the affective component introduced greater intensity at both the Organizational Commitment (M = 4,161) and the Professional (M = 4,912). Secondly, calculative component arises also in Organizational Commitment (M = 3,368) or Professional (M = 3,840). The normative component, with the lowest average, presented identical values in both types of commitment (respectively of M = 3,098 and M = 3,036). Components of Professional Commitment were all higher than those of the Organizational Commitment; differences were tested statistically through the t-student's test. The difference between the normative components has not been tested statistically significant (t = 0,893, sig = 0,373). All components of the Organizational Commitment and Professional Commitment correlate positively with each other, although three of these relationships are not statistically significant.

The strongest relationships were observed between the corresponding components of Organizational Commitment and Professional Commitment, which were in line with the results obtained by Meyer and colleagues (1993), as well as other studies (e.g., Jones & McIntosh, 2010; Tsoumbris & Xenikou, 2010). Also the affective and normative components of Organizational Commitment showed a positive relationship, like the results of the meta-analysis of Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky (2002), as well as other researchers (e.g., Jones, McIntosh & 2010; Meyer, Stanley, & Parfyonova, 2012; Xenikou & Tsoumbris, 2010). As to the Professional Commitment, a stronger relationship was found between the normative and calculative components, and shortly thereafter between the affective and normative, with slightly more moderate values. These results are consistent with those of Tsoumbris and Xenikou (2010), although the strongest relationship tends to be between the affective and normative components (e.g., Chang, Chi, & Miao, 2007; Meyer et al., 1993; Snape & Redman, 2003).

Test of Hypotheses and Comparison of Models

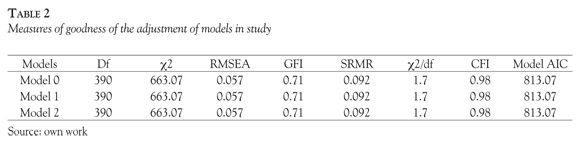

The Null Model (Mo), the first model (M1) which established the Professional Commitment as a determinant of Organizational and the second (M2) in which the opposite was established were initially tested. Results suggest an adjustment equal to goodness the three models (table 2). It was found that adjustment measures are within the bounds of acceptability. However, the SRMR and GFI deviate slightly from the reference values. However, Hair and colleagues (2010) argued that the complexity of the model could lead to a "... problem of an unjust punishment." (p. 751) and unfairly affect these types of indicators. Nor is irrelevant the fact that we used a sample with a lower dimension than the recommended, which will influence this type of measures of goodness of adjustment more sensitive and more affected by the error of estimate.

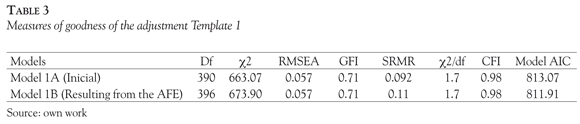

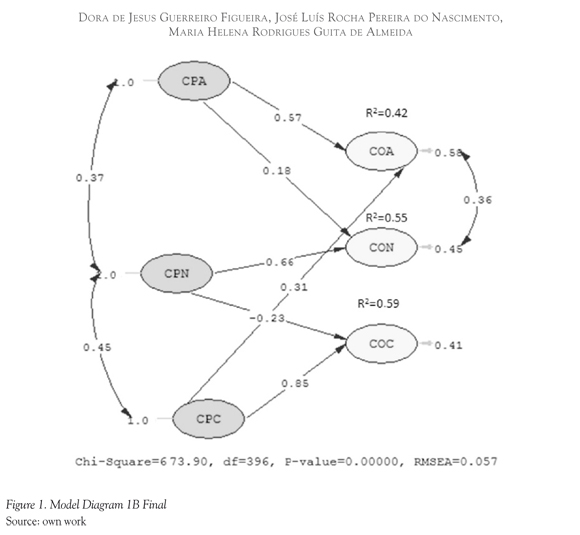

This conditionality may have contributed to not having a difference between the adjustments of the three models. We then review the proposed Ml (M1A), after having successively eliminated structural relations statistically non-significant. Thus, we obtained a final proposed model (M1B) that presented a goodness of acceptable adjustment (Table 3).

It was found in M1B final (fig. 1) that in the affective component only Organizational Commitment was related to the normative. In regards to Professional Commitment, the existence of a relationship between affective and normative component was verified, as well as between the normative and the calculative. It was also verified that the components of Professional Commitment positively determined the components of the same kind of Organizational Commitment. Finally, the calculative component determined positively the affective component.

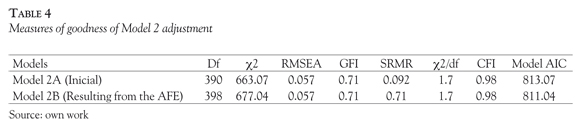

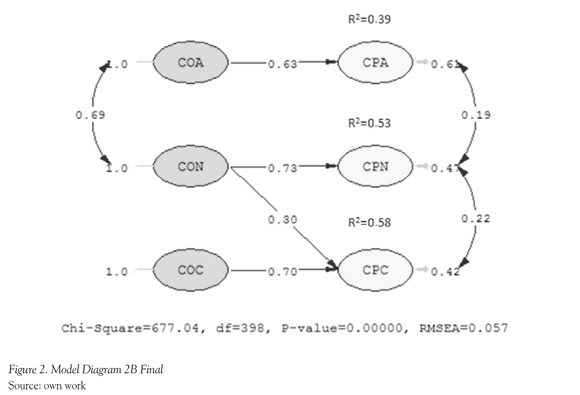

The coefficient of determination of each component of the Organizational Commitment (R2) was greater than 0,4, suggesting a good explanatory capacity of Professional Commitment components in determining Organizational Commitment. Using a similar procedure to that used in M1 to the second model (M2), in addition to the initial model (M2A), another model was tested that resulted from the elimination of non-significant statistical relationships (M2B). The final proposed model (M2B) presented a better adjustment, despite the limitations mentioned previously (table 4).

In the second final model (fig. 2), it was found the existence of a relationship between affective and normative component of the Organizational Commitment of greater intensity than the ratio found in the first final model, and of lesser intensity between the affective component and to rules and regulations than the calculative Professional Commitment.

Similar to what was found in the first final model, also in this model the components of Organizational Commitment determined the components of the same kind of professional Commitment. As the results obtained for model 1, also in model 2 the values of the coefficient of determination of the dependent variables are greater than 0.4 (fig. 2), suggesting an explanatory capacity variance of professional Commitment through Organizational Commitment (independent variables). However, these values are slightly lower than those of model 1 (specifically of 1% on the normative components and calculative and 3% in the affective component). Established and tested both models, we moved to the comparison of the models in order to know whether there would be one that show a better kind of adjustment and, therefore, a better statistical validity. Both final models (table 5) presented an acceptable adjustment, even though the value of GFI (0,71) is slightly lesser than the recommended value, and the value of SRMR (0,11) lies slightly above the reference value, as I commented earlier, not being able to infer a better adjustment of either of the two models from the study.

We have to point out that the measurement value Model AIC is slightly lower (0,87) in M2 end relative to the M1, this could lead to the possibility that Organizational Commitment is determinant to Professional Commitment. In fact, according to Salgueiro (2008), as well as Hair and colleagues (2010), the smallest measurement value Model AIC is an evidence of a better model set. In light of the reduced value obtained, it was decided to also compare both models through the Chi-square test, similar to the process used in multi-groups (Salgueiro, 2008). Considering the difference of 2 degrees of freedom, the difference between the Chi-square value obtained in each model should be higher than 5,99. The difference obtained was 3,13 (A x2 = 677,04 -673,9), so the null hypothesis is not rejected, not being able to infer the statistical difference between the two models. Despite

this conclusion we have to highlight the fact that Model 2 has a smaller number of relations of determination, only showing a single relationship between two compromises of different nature, in particular the relationship of determination between the Organizational normative and the Professional Commitment calculative. In Model 1 the relationship of determination between variables of different natures are of greater values, in particular, between the Professional Commitment affective and the Organizational Commitment normative, as well as between the Professional Commitment normative and the Organizational Commitment calculative, and between the Professional Commitment calculative and the Organizational Commitment affective. On the other hand, values of R2, as discussed earlier, are slightly higher than those recorded in model 2. There are signs of a better explanatory capacity of model 1, which suggests a possible advance of Professional Commitment on Organizational Commitment, despite not being statistically verified in the present study.

Discussion and Conclusions

Considering the indicators of goodness of both adjustments, the model of Professional Commitment is more consistent and presents a better fit to the data than the model of Organizational Commitment. These results suggest that academics are more committed to the profession than with the organization where they exercise their profession, which is consistent with other empirical studies using professions with high professional culture and identification (e.g., Chang et al., 2007; Jones & McIntosh, 2010; Meyer et al., 1993; Xenikou & Tsoumbris, 2010). Professor's commitment, either with the profession or with the Organization, is predominantly of affective and calculative nature. These results are common in the literature and have been identified in both constructs in other studies (e.g., Irving et al., 1997; Snape & Redman, 2003; Jones & McIntosh, 2010; Tsoumbris & Xe-nikou, 2010; Williams et al., 2012).

Results point to the desire of professors to remain in the profession and in the Organization (in this case, the University) because they like them and are affectively connected to them, but to do so they have to be accompanied by a material or instrumental necessity. For Meyer (2009) organizational changes, in particular, those that result in staff reductions, have the potential to influence the three forms of Commitment, in particular the calculative commitment. Job insecurity and limited availability of alternatives may lead to the development of this type of commitment on workers, who understand the fragility of their situation, as well as to change the orientation of their commitment to other forms that exist in the workplace, other than the organizational. Of all the relationships of statistically significant determination, it is important to reflect on the single interface that is common to both models, in particular, the relationship of determination of Professional normative Commitment over the Organizational Commitment calculative in Model 1 and the Organizational Commitment normative over the Professional Commitment cal-culative, in Model 2.

In the first model the relationship of determination between the two constructs is negative, while in the second model is positive. This result suggests that a strong sense of obligation and duty in relation to the profession may outweigh the investments made in the organization and the costs associated with an eventual exit. So, facing the hypothetical need to have to choose between the profession and the organization, the professor would choose his profession, even with loss of material conditions. In contrast, in model 2 it was found that the presence of a strong sense of duty in relation to the organization would be translated as gain/investment in relation to the profession, giving rise to a high cost, relatively to a possible change of profession.

Both situations are admissible, in the first case because of its strong cultural identity (Sainsaulieu, 1988) the profession overlaps the organization and, in the second case, the sense of obligation and duty in relation to the organization would enhance the value of the profession, thus, increasing the costs associated with an eventual change of profession. On the other hand, it was the affective components of professional or Organizational Commitment that showed greater intensity, suggesting that the primary nature of the relationship was the affective. Therefore, in a context of profound organizational changes and social crisis, it is important to not only manage the change in the type of commitment, but also, and above all, changes in their nature (Meyer, 2009), implying that a human resource management of a more Dialogic nature than dialectic (Lopes, 2012), more demand-driven rather than supply-driven (Bilhim, 2009) and more oriented towards the management of affections.

Although we have not found statistically significant differences between the two models proposed, and we cannot claim that Professional Commitment is an antecedent of Organizational Commitment (M1) or its inverse (M2), there is evidence to support the possibility of a better match of the first model. In fact it is a more explanatory model because, on the one hand, it presents a greater number of relationships of determination and, on the other, independent variables (Professional Commitment) best explain the variance of dependent variables (Organizational Commitment). In addition, it is also the model that best fits the theoretical framework that proposes the determination of professional commitment over the organizational. This theoretical framework is based on a more personal nature than contextual or organizational, of the Professional commitment and should therefore be an antecedent of Organizational Commitment (e.g., Meyer & Allen, 1997; Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001; Meyer et. al., 2002).

Of all the limitations identified and referred previously, the reduced sample size for the methodologies used suggests to replicate the study with a larger sample, in order to confirm the results obtained. The absence of multi-groups analysis is another limitation due to sample size, which impeded to check for possible moderating effects of other variables such as demographic profiles or compromising profiles in of the study models. In conclusion, this study highlighted the fact that being faced with several alternatives supported by theoretical and empirical studies that, being seemingly contradictory in a perspective of complementarity, may allow the identification of the relations determined to provide a better explanation of a specific facet of the relationship collaborator/organization.

References

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1996). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: An examination of construct validity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49(3), 252-276. [ Links ]

Aranya, N., Pollock, J., & Amernic, J. (1981). An examination of professional commitment in public accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 6(4), 271-280. [ Links ]

Becker, H. S. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66, 32-42. [ Links ]

Becker, H. S., & Carper, J. W. (1956). The development of identification with an occupation. American Sociological Review, 2(3), 341-348. [ Links ]

Blau, G. (1985). The measurement and prediction of career commitment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 58, 277-288. [ Links ]

Bilhim, J. (2009). Gestae Estratégica de Recursos Humanos (4th ed.). Lisboa: ISCSP. [ Links ]

Chang, E. (1999). Career commitment as a complex moderator of organizational commitment and turnover intention. Human Relations, 52(10), 1257-1278. [ Links ]

Chang, H.-T., Chi, N.W., & Miao, M. C. (2007). Testing the relationship between three-component organizational/occupational commitment and organizational/occupational turnover intention using a non-recursive model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(2), 352-368. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. (2007). Dynamics between occupational and organizational commitment in the context of flexible labor markets: A review of the literature and suggestions for a future. Bremen: Universität Bremen. Retrieved from http://itb.uni-bremen.de/fileadmin/Download/publikationen/forschungsberichte/fb_26_07.pdf. [ Links ]

Dwivedula, R., & Bredillet, C. (2010). The relationship between organizational and professional commitment in the case of project workers: Implications for project management. Project Management Journal, 41(4), 79-88. [ Links ]

Gouldner, A. W. (1957). Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles I. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2(3), 281-306. [ Links ]

Gouldner, A. W. (1958). Cosmopolitans and locals: Toward an analysis of latent social roles II. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2(4), 444-480. [ Links ]

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson, Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Irving, P., Coleman, D., & Cooper, C. (1997). Further assessments of a three-component model of occupational commitment: Generalizability and differences across occupations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 444-452. [ Links ]

Johnson, R. E., Groff, K. W., & Taing, M. U. (2009). Nature of the interactions among organizational commitments: Complementary, competitive or synergistic? British Journal of Management, 20(4), 431-447. [ Links ]

Jones, D. A., & Mcintosh, B. R. (2010). Organizational and occupational commitment in relation to bridge employment and retirement intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 290-303. [ Links ]

Klein, H. J., Molloy, J. C., & Brinsfield, C. T. (2012). Reconceptualizing workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: Revisiting assumptions and removing confounds. Academy of Management Review, 37, 130-151. [ Links ]

Klein, H. J., Molloy, J. C., & Cooper, J. T. (2009). Conceptual foundations: construct definitions and theoretical representations of workplace commitments. In H. J. Klein, T. E. Becker., & J. P. Meyer (Eds.), Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions (pp. 3-36). New York: Routledge, Taylor & Fracis Group. [ Links ]

Ko, J., Price, J., & Muller, C. (1997). Assessments of Meyer and Allen's three-component model of organizational commitment in South Korea. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 961-973. [ Links ]

Lachman, R., & Aranya, N. (1986). Evaluation of alternative models of commitments and job attitudes of professionals. Journal of Occupational Behaviour, 7 (3), 227-243. [ Links ]

Lee, K., Carswell, J. J., & Allen, N. J. (2000). A meta-analytic review of occupational commitment: Relations with person- and work-related variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 799-811. [ Links ]

Lopes, A. (2012). Fundamentos para a Gestao de Pes-soas: Para uma Síntese Epistemológica da Iniciativa, da Competiqao e da Cooperacao. Lisboa: Edicóes Sílabo. [ Links ]

Maroco, J. (2010). Análise de equacóes estruturais: Fundamentos teóricos, software e aplicacóes. Pero Pinheiro: Report Number. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P. (2009). Commitment in a changing world of work. In H. J. Klein, T. E. Becker, & J. P. Meyer (Eds.), Commitment in organizations: Accumulated wisdom and new directions (pp. 37-68). New York: Routledge, Taylor & Fracis Group. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 61-89. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. California: SAGE Publication, Thousand Oaks, [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., & Herscovitch, L. (2001). Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11, 299-326. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., & Parfyonova, N. M. (2010). Normative commitment in the workplace: A theoretical analysis and re-conceptualization. Human Resource Management Review, 20(4), 283-294. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, (4), 538-551. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topol-nytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20-52. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, L. J., & Parfyonova, N. M. (2012). Employee commitment in context: The nature and implication of commitment profiles. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 1-16. [ Links ]

Morrow, P. C. (1983). Concept redundancy in organizational research: The case of work commitment. The Academy of Management Review, 8(3), 486-500. [ Links ]

Nascimento, J., Lopes, A., & Salgueiro, M. (2008). Estudo sobre a validacáo do Modelo de Comportamento Organizacional de Meyer e Allen para o contexto portugués. Comportamento Organizacional e Gestào, 14(1), 115-133. [ Links ]

Neumann, Y., & Finaly-Neumann, E. (1990). The reward-support framework and faculty commitment to their university. Research in Higher Education, 31(1), 75-97. [ Links ]

Randall, D. M., & Cote, J. A. (1991). Interrelationships of work commitment constructs. Work and Occupations, 18(2), 194-211. [ Links ]

Rego, A., & Souto, S. (2004). A percepcao de justica como antecedente do comprometimento organi-zacional: Um estudo luso-brasileiro. RAC, 8(1), 151-177. [ Links ]

Reichers, A. E. (1985). A review and reconceptualiza-tion of organizational commitment. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 465-476. [ Links ]

Sainsaulieu, R. (1988). Lldentité au Travail (3rd ed.). Paris: Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques. [ Links ]

Salgueiro, M. F. (2008). Modelos de equagoes estruturais: Aplicagoes com LISREL (Unpublished document), ISCTE: Lisboa. [ Links ]

Snape, E., & Redman, T. (2003). An evaluation of a three-component model of occupational commitment: Dimensionality and consequences among United Kingdom human resource management specialists. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 152-159. [ Links ]

Tsoumbris, P., & Xenikou, A. (2010). Commitment profiles: The configural effect of the forms and foci of commitment on work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 401-411. [ Links ]

Vandenberg, R., & Scarpello, V. (1994). A longitudinal assessment of the determinant relationship between employee commitments to the occupation and the organization. Journal of Organizational Behavior, l5, 535-547. [ Links ]

Wallace, J. E. (1995). Organizational and professional commitment in professional and nonprofessional organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 228-255. [ Links ]

Wasti, S. A., (2005). Commitment Profiles: Combinations of organizational commitment forms and job outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 290-307. [ Links ]

Williams, H., Rayner, J., & Allinson, C. (2012). New public management and organizational commitment in the public sector: Testing a mediation model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(13), 2615-2629. [ Links ]