1. Introduction

In November 2016, the Colombian government signed a Peace Agreement with the current political party Common Alternative Revolutionary Force - FARC (Spanish: Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común). One of the expectations generated by this agreement was to create the democratic opening conditions for the expression of differences in the country (Point 2 of the Agreement). Despite this, in Colombia it has not been possible to consolidate a political regime that allows participation and protects life (Ángel, Nieto and Giraldo, 2019).The National Civil Registry, the Center for Studies in Democracy and Electoral Affairs -CEDAE- and the Center for Analysis and Public Affairs -CAAP-, thus acknowledge it, stating that in:

The Colombian regime, four institutional failures - traversed by dynamics of security - persist to guarantee the exercise of democracy: a) Guarantees for the exercise of the opposition; b) Guarantees for freedom of expression; c) Guarantees for the association; and d) Guarantees for social movements. This is observed in the high amount of repression actions, with persecution, homicide rates and the political genocide of political actors, that have restricted even more the political exercise of the opposition in Colombia (Londoño, 2016, p97).

Resolving institutional failures that impede protection of life and the democratic exercise of the country, has been one of the intentions of the Peace /Agreement signed in 2016 between the Colombian Government and the FARC-EP. However, the political regime has not allowed adequate political participation by the opposition. The Colombian State continues to develop practices in which the lack of guarantees for the exercise of democracy persists, such as the stigmatization of the opposition, the threat and murder of social leaders in various areas of the country (Ángel, Nieto and Giraldo, 2019). The new FARC political party has had to assimilate that participation in politics and the struggle to consolidate peace imply sabotage problems of the process, both by the State and the government at the head of the Democratic Center party, a party that assumed the banner of representing the population that does not believe in dialogues with the FARC (Losada and Liendo, 2016; Rey, 2015).

In Colombia, through the Peace Agreement signed in 2016, the need to make not only formal changes but also to allow the conditions for political participation of the opposition is recognized. However, this recognition has not met its materialization, on the contrary, the selective murders of social leaders throughout the country have increased (El Tiempo, 2019; Indepaz, 2019).The political participation of the opposition in Colombia cannot be analyzed outside the social context of the country, in which there is evidence of a political regime that supports the systematic and generalized violation of human rights. Poverty, inequality, corruption, and environmental deterioration are the correlate of the difficulties that the participation in politics has, especially for the rural communities of the country, which have been the most affected.

This research article raises the question: Does the signing of the Peace Agreement, in 2016, achieve that the Colombian political regime provides guarantees for the exercise of democracy, expressed in guarantees of exercising the opposition, freedom of expression, union association and social movements? To answer this question, firstly, the elements of discussion on the issue of political opposition are addressed, and secondly, how this is carried out in Colombia after the signing of the Peace Agreement in 2016 between the Colombian Government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People's Army FARC EP, currently the political party Common Alternative Revolutionary Force (Spanish: Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común) -FARC. As a working hypothesis, it is considered that the Colombian political regime has not provided sufficient guarantees for the participation and exercise of democracy and that the current government has allowed the conditions for the political, social and armed conflict to be sharpened.

The article makes an important contribution to the novel interpretation of a historical moment in which Colombian society seeks peaceful solutions to the political, social and armed conflict, despite the fact that the current government persists in sabotaging what was signed in 2016 in the Peace Agreement and maintains a regime in which political participation is limited and the opposition is penalized, even with the death of social leaders.

2. Methodology

The method of analysis adopted is interpretive and inductive, with a focus on the political participation of the opposition in a broad sense and not only focused on the analysis as an I opposition political party; this is to account as the research objective, namely, to determine if the Peace Agreement signed in 2016 allows that the Colombian political regime provides guarantees for the exercise of democracy, expressed in guarantees to exercise opposition, freedom of expression, union association and social movements.

The analytical phases of the process were developed in the following order; first, a consultation of research aimed at explaining the exercise of opposition political participation in a broad sense, without restricting the opposition to one or more political parties, with emphasis on the FARC party since it was the signatory of the Peace Agreement; second, news and data were gathered on movements and social leaders throughout the country. Then, the information obtained was critically analyzed considering a) Guarantees for the exercise of the opposition; b) Guarantees for freedom of expression; c) Guarantees for the association; and d) Guarantees for social movements. In this last case, an emphasis on the communities in rural areas was placed, considering that the Peace Agreement assumes an important commitment to them.

The news tracking was carried out through a qualitative analysis matrix to identify the most relevant ones that would explain and account for the research objective. For this analysis, national media such as El Tiempo, El Espectador, Semana Magazine, and FARC and other social organizations statements on this issue of political participation were reviewed.

3. Results and Discussion

Political opposition is a fundamental right and is not limited only to political parties and movements. This right extends to all citizens and, therefore, all citizens are empowered to participate in the control of political power (Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy-NIMD, 2019). The political opposition is not limited to the work carried out in the Congress of the Republic. The exercise of the opposition occurs in a broader framework determined by context variables, including the existing political party system, electoral processes, social equality, existence of -cultural, regional, political- pluralism among others (NIMD, 2019).

An important improvement of the I99I Constitution was to establish the role of the opposition at the institutional level (Giraldo, 2014), and it is elevated to a fundamental right by the Status of the Opposition (NIMD, 2019). After the signing of the Peace Agreement in 2016, Colombian society hoped that the political regime would provide guarantees for the exercise of democracy, which can be expressed in guarantees of exercise of the opposition, freedom of expression, union association and social movements; so hereunder it is shown and discussed what has been evidenced in the real state of each one of these aspects.

3.1. Guarantees of exercise of the opposition

In Colombia, an anti-opposition practice predominates excluding and marginalizing from the political arena the initiatives that different social movements and forces of the country seek to express in pursuit of the required transformations. This anti-opposition state contrast with experiences of incorporation into political life, such as those reported by:

All opposition groups who fought during the conflict ended occupying positions of responsibility in new emerged governments after the Peace Agreements, this in the cases of El Salvador Guatemala, Northern Ireland, South Africa, Tajikistan, Sierra Leona, South Sudan, Burundi, Indonesia and Nepal (Fisas, 2010, p. 5).

In order to understand the difficulties that the political participation of the opposition continues to have in Colombia after the Peace Agreement, the works of Manning (2004) may be of interest, who has studied the armed opposition groups in political parties, comparing the cases of Bosnia, Kosovo and Mozambique. Manning (2004) argues that all transitions from war to peace, mediated by democratization processes, present two major types of organizational challenges: those that imply adjustments in the relationships between elites, and those that require changes in which the parties try to attract a massive tracking, called collective incentive strategies. The specific mix of challenges is influenced by institutional factors, international intervention, and historical context, among others.

The current Colombian government has used warlike language that makes the transition from conflict to peace difficult. Because electoral politics requires a different set of skills than those required in times of conflict, a transition from confrontation can change the sources of organizational power and authority. Not only the institutional configuration of the political arena, but also the substantial outcome of the peace agreement influences the probability that the parties are willing and are able to invest in the new rules of the game (Manning, 2004).

In Colombia, the institutional design makes it difficult for all social groups that are separate from the interests of the ruling political regime to participate into politics. In this regard, Blattman (2008), in his analysis of the war and political participation in Uganda, argues that the social sciences have yet to produce a theory that is standard and empirically supported on political participation.

The violence of war creates grievances that increase the inherent value that individuals place on political expression, motivating them to increase community leadership. This interpretation may explain, at least in part, why the FARC remains committed to the Peace Agreement in the middle of post-conflict violence. And this explanation is not something minor, as other experiences of peace processes in the world indicate that of 38 peace agreements signed between I988 and I998, 3I did not last more than three years (Pearlman, 2009).

In the Colombian case, the historical review has shown that the difficulties in being part of the opposition have to do with State policies (Guarín, 2006). The peace processes that culminated in the demobilization of some insurgent groups, and their participation through institutional channels, marked Colombian politics during the first part of the 1990s. The guerrillas of the 1970s and 1980s succeeded in questioning power structures and placing fundamental issues such as human rights, democracy, justice, peace, and militarization on the national agenda (Flórez and Valenzuela, 1997).

This Colombian dynamic of the I990s coincides with the analyzes of Welsh (1994), who, when comparing the processes of political transition in Central and Eastern Europe, finds that regardless of the mode of transition, the concept of negotiation is crucial to understand the peace process. Welsh's argument is based on the assumption that negotiators need to reach some agreement, but at the same time want to settle on favorable terms themselves (Welsh, 1994).

These analyzes contrast with one of the underlying assumptions of much of the literature on transitions, according to which, the way in which new regimes are created has important implications for the stability of the emerging polyarchy. These transition modes are generally distinguished according to the process through which the incumbents are replaced by the opposition force. Roughly, there are transitions from above (transformation / transaction / reform), transitions from below (substitution / rupture / rupture), and transitions where the regime and the opposition play a role almost the same in the transformation system (translocation /elimination). Considering the different patterns of negotiation, contributes to a better understanding of the transition process, allowing to distinguish between different stages of the transition process without having to relying solely on specific events such as foundational elections. For Welsh (1994), different stages of the transition process are defined by different modes of conflict resolution.

In this approach, the successful transition process towards democratic political government involves three stages. First, the liberalization of the authoritarian regime is accompanied by declines in the use of order and imposition as the prevailing modes of conflict resolution. Second, as the transition progresses to the elimination of the old regime and the institutionalization of a new political system, negotiation and commitment emerge as the main characteristics of decision making. Finally, the consolidation of the transition is distinguished by the predominance of competition and cooperation as the predominant means of conflict resolution.

In Colombia, where with the signing of the Peace Agreement in 2016 the third stage noted above was evidenced, the current government refuses to make the changes promised. Additionally, the efforts of Colombian society and the international community have been insufficient. In the case of society, both because of its silencing enforced by various actors, and because of the violence exercised against the opposition forces. And in the case of the international community because there has not been enough dissemination and follow-up on what was agreed.

Humphreys and Weinstein (2008) point out that understanding the motivations of combatants can shed light on the origins and evolution of these conflicts. And it also helps in the evaluation of conflict resolution and reconstruction strategies in the post-conflict period. If insurgent armies have been forged through the promise of resource rents from mineral extraction, peacemaking may depend on the ability of outside actors to buy the support of potential saboteurs. If these armies have motivated participation by mobilizing popular discontent towards government policies, post-conflict agreements must give a more serious consideration to the establishment of institutional arrangements focused on discrimination, oppression, and inequality.

From the findings of Humphreys and Weinstein (2008) it is possible to deduce that in the Colombian case there is a greater commitment from the now FARC political party with the Peace Agreement due to its dissatisfaction with a political regime that sustains inequality, the environmental crisis and poverty. They also imply that the discontent, when presented through individuals in a particular social class or ethnic group, provides the basis for the mobilization and the initiation of violence against the State. The reluctance of the Colombian government to comply with the Peace Agreement contrasts with the firm position of the FARC.

Pearlman (2009) affirms that where parties kept saboteurs at bay, as in Guatemala and South Africa, bloody years gave way to successful transitions to peace and democracy; while where the saboteurs were successful, as in Angola and Rwanda, the violence that occurred after the failure of the agreement was more horrible than the previous one. In Colombia, the current government party, Democratic Center party, tries to make the Peace Agreement signed in 2016 fail. The rhetorical strategies used by the Democratic Center party have generated that the public opinion understands the peace dialogues within the framework of the warmongering interpretation, which leads to a radical denial of the project of ending the conflict through dialogue. To understand negotiations as a confrontation is to move away from the approach assumed by the process and introduce a discussion in the public sphere that separates the debate from fundamental issues, such as the contents of the agreements (Olave and Cediel, 2015).

In the Colombian case, the acts of intolerance against the emerging FARC party in the cities of Armenia, Yumbo and Cali, prior to the first round of presidential elections of the 2018-2022 period, showed that the exercise of violence against the political opponent did not only belong to the daily terrain, through killing social leaders and ex-combatants: but it is also exercised in the field of electoral politics (Casey, 2018).

Pearlman (2009) asserts that a peace process is a sustained effort to negotiate a lasting solution to a prolonged conflict between States and/or non-state groups. Actors dissatisfied with the terms of an agreement engage in a sabotaging behavior, unless third parties suppress, accommodate, or co-opt them as required to address these actors toward greedy, limited, or total goals. Saboteurs use violence because it is more effective than negotiations in forcing democracies to give up territory. Saboteurs plan attacks to undermine trust. In Colombia, despite the intensity of the sabotage of what was agreed by the Democratic Center party, former FARC combatants continue to affirm their commitment to the consolidation of sustainable and lasting peace, outlined in the 2016 Agreement.

While the FARC has shown its commitment to the transformations that the country needs to overcome its humanitarian crisis (Zonacero.com, 2019), the studies by Mora (2017) and Olave and Cediel (2015) show how the political parties that have historically governed , generated and promoted armed conflicts, in different worldwide experiences oppose the peace accords and sabotage them, it is evident in the case of the Democratic Center party in Colombia.

3.2. Guarantees for freedom of expression

Murder is one of the most common ways of violating freedom of expression in Colombia, this last one is enshrined as one of the fundamental rights in article 20 of the I99I Political Constitution, in which, in a formal way, "Everyone is guaranteed freedom to express and disseminate their thoughts and opinions, to inform and receive truthful and impartial information, and to found mass media. These are free and have social responsibility. The right to rectification under conditions of equity is guaranteed. There will be no censorship".

Although it is recognized that freedom of expression is a fundamental pillar for the construction of a democratic society - according to the Constitutional Court, 2013, sentence T-256, magistrate Jorge Ignacio Pretelt Chaljub (Arboleda, 2014); In Colombia, freedom of expression is violated through threats, kidnappings, assassinations against journalists and social communicators (Londoño, 2016; Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica -CNMH, 2015, Fundación Para la Libertad de Prensa -FLIP, 2019). Historically, the Colombian State has been an instrument that concentrates violence and channels it to eliminate the opposition (Revollo, 2018; Giraldo, 1994; Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica -CNMH, 2013). The Peace Agreement signed in 2016, meant the recognition, by the Colombian Government, of the need to carry out profound transformations in the State to generate conditions for freedom of expression and the implementation of different kind entrepreneurships (Botello-Peñaloza and Guerrero-Rincón, 2017; García-Macías, Zerón-Felix and Sánchez-Tovar, 2018; Díaz-Fernández and Echevarría-León, 2016).

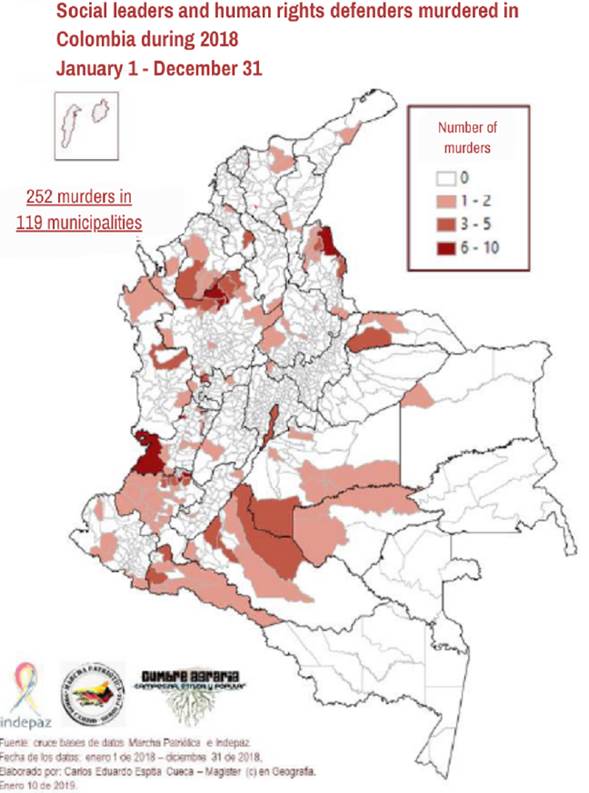

However, the selective murders of social leaders, union leaders and communicators, perpetrated by the State or with its complicity, in all regions of the country (El Tiempo, 2019), have targeted not only political opponents belonging to the FARC party but also social expressions that disagree with the economy policy of the country (Indepaz, 2019) (Figure 1).

Source: Indepaz Institute of Studies for Development and Peace (Spanish: Instituto de estudios para el desarrollo y la paz) (2019).

Figure 1 Social leaders and human rights defenders murdered in Colombia in 2018.

Ávila (2017), in a column in the newspaper El País, affirms that in the country the collusion between political parties, high courts, the office of the attorney general of Colombia and electoral body is so large that opinion can be censored. The Press Freedom Foundation -FLIP (Spanish: Fundación para la libertad de prensa), in the "Report on the state of press freedom in Colombia 2019. Silence and pretend, the usual censorship " evidence that despite the signing of the 2016 Peace Agreement the transformations have not been performed to generate conditions for freedom of expression. FLIP (2019) document:

515 attacks on the country's press, of which 137 were threats, 4 were kidnappings and 2 homicides.

66 journalists were attacked during days of national strike.

I25 murders of journalists, out of I59, go unpunished

15 bills seek to limit expression on the Internet

1,100 people were fired from the media communication in Colombia

66 cases of judicial harassment that affected 75 journalists

3. 3. Guarantees for the association and social movements

In Colombia, the government promotes a context of systematic violation and generalized guarantees for the union association and social movements, which shows a disinterest in democracy and peace (Castrillón-Torres and Cadavid-Ramírez, 2018, p. 151 ). Murillo's studies (2019) on the prospects of the Peace Agreement conclude that the way the government creates a climate of uncertainty that extends to other urgent topics from the official agenda: it does not consider the - nstitutional, economic and human - resources available and does not operate under a democratic logic.

The "Report on Human Rights Violations of trade unionists in Colombia, 2016-2018. The peace is built with guarantees for freedom of association", published in May 2019 by the National Union School, shows that, after the signing of the Peace Agreement in 2016, violence Anti-union is not an outdated phenomenon and continues to be a violation of the human rights of trade unionists, a serious obstacle to freedom of association and a way of treatment based on exclusion and stigmatization (Colorado, Trujillo, Ortiz and Amado, 2019). According to this, Peace Agreement of 2016 has not meant the overcoming of persecution and violence against unions and trade unionists, on the contrary, homicides have increased (Table 1).

Table 1 violations of life, liberty and integrity committed against trade unionists in Colombia, 2016-2018.

| Type of violation | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | General total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threats | 202 | 137 | 172 | 511 |

| Homicides | 20 | 22 | 34 | 76 |

| Harassment | 30 | 26 | 8 | 64 |

| Attacked with or without injuries | 18 | 17 | 10 | 45 |

| Arbitary detention | 5 | 9 | - | 14 |

| Illegal break-in | 8 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Enforced disappearance | - | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Forced displacement | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Torture | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| General total | 286 | 215 | 231 | 732 |

Source: Colorado et al. (2019, p. 22), based on Human Rights Information System (Spanish: Sistema de Información en Derechos Humanos), Sinderh.

The 2016 Peace Agreement has not meant that the organizations and social movements may dissent from the political regime, and, therefore, help lay the bases for democracy and peacebuilding. From this perspective, it is valid to consider that, for the democratic construction, the opposition is necessary since it allows a thoughtful search for social progress, with the contribution of the expression of a true social and political pluralism that drives social longings in public policies (De la Cruz and Ariza, 2017).

On May 7th 2018, I08 social and human rights defenders organizations from the Colombian south and of national order raised, by means of a statement, their request towards the international community to make the necessary efforts in order to stop the persecution and attack suffered by human rights defenders and leaders and women leaders of the Colombian social movement (Coordinador Nacional Agrario - CNA, 2018). The statement brings to light the "state terrorism against the social movement and its historical genocidal practice, against the social leaders and women leaders" (CNA, 2018, p. 1).

It is not possible to expect that the Colombian State acknowledge that there are no guarantees for expressions of the country's social movements. In Colombia, rural organizations and social movements in the country, have been the most affected by the political, social, and armed conflict, they find in the State the main obstacle for the achievement of peace (ONIC, 2018; CRIC, 2019). This consideration is supported by CEPAL (2018) and FAO (2018) studies, according to these multilateral organizations structural poverty in rural sectors remains alarmingly high. CEPAL estimations (2018), point out that in 2016 the percentages of the population in situation of rural poverty and extreme rural poverty in Latin America reached 48.6% and 22.5%, respectively. These levels are considered extremely high (FAO, 2018) and hinder the challenges implied for the country because of the growing rise of the digital economy in the world (Calle-Álvarez and Sánchez-Castro, 2017).

In Colombia, reducing rural poverty can be accomplished through a rural Territorial Development approach (FAO, 2018, as stipulated in the Peace Agreement, which allows achieving less food insecurity, reduce migratory pressure on urban areas, reduce social unrest and avoid the degradation of ecosystems; moreover, that it boosts the productive capacity and the economic contribution of the rural poor (Sánchez-Jiménez, Nieto-Gómez and Giraldo-Díaz, 2018). Despite having signed the Peace Agreement in 2016, which discerns this development approach, the State guides policies that exacerbate the political, social, and environmental problems of rural populations (Alzate, 2018).

It seems that the Colombian government assumed two ways of acting within the framework of negotiations, since in Havana spun a rhetorical discourse that gave shape to a difficult dialogue between two historically opposed parties without allowing the emergence of creative agreements for the reconciliation; on the other hand, in Colombia the same government and in the full exercise of its governmentality, it unravels and does not recognize what was agreed. With the Peace Agreement, the hopes of rural populations emerged, those mired in multidimensional rural poverty (FAO, 2018). Although the FARC have committed to what was agreed, throughout and across the country these hopes are interrupted by state violence (Indepaz, 2019; ONIC, 2019, The Colombian State does not help to overcome poverty and the humanitarian crisis of rural societies, on the contrary, state policies sharpen them.

Colombian rural social movements and organizations promote and develop actions tending to the real overcoming of the social and armed conflict in the country. These actions include social and political organizational initiatives that are persecuted by the Colombian State (Indepaz, 2019; ONIC, 2019).That is how some political organizations born as a product of the grouping, mostly trade unions, student organizations and social based organizations, have served for the generation of recent political parties and movements that have attempted to distance themselves from the Government through the exercise of the opposition, this exercise might be blurred many times basically by two fundamental circumstances: the inability to generate governance for leftist governments, either by his own sectarianism, or by the sectarianism of those who oppose and due to the lack of ideological definition (De la Cruz and Ariza, 2017).

Jorge Eliecer Gaitán vindicated the opposition in order to build new social structures, to rethink property, work, politics, and social projection rights, especially of those from disadvantaged classes in the country. It is the inclusion of the different ways of living that coexist within society and they must interact among them to be able to generate the balance of social progress (De la Cruz and Ariza, 2017).

4. Conclusions

The Peace Agreement signed in 2016 did not mean the end of the political, social, and armed conflict or that the Colombian political regime provide sufficient guarantees for political participation and the exercise of democracy.

The 2016 Peace Agreement failed to overcome the anti-opposition practices and to generate guarantees so that the opposition express initiatives in the political arena from different social movements and living forces of the country seeking to carry out the transformations required by society.

After the signing of the Peace Agreement in 2016, the guarantees for freedom of expression in Colombia have not been generated.

The 2016 Peace Agreement has not guaranteed that trade union associations and social movements can help build new social structures that contribute to the construction of democracy and peace in Colombia.

For future research on the implementation of the Peace Agreement, it is recommended to take into account the participation approach of society, in order to assess whether there has been progress in the necessary transformations for the proper exercise of the opposition in Colombia.