Introduction

Understanding sustainability challenges academics and researchers due to its complex nature and many factors involved in its execution in different areas of society. According to Verk et al. (2021), sustainability involves greater organizational participation and communication to resolve the contradictions between social and business concerns. Many companies recognize that, at present, incorporating the principles and criteria of sustainability into their corporate cultures and their operations is a necessary competitive factor for their success in the medium and long term (Morioka et al., 2017). From this point of view, the participation of the private sector in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations General Assembly) should not only be approached from a corporate social responsibility (CSR) point of view but as an opportunity to adopt and transform business models (ECLAC, 2019).

According to Aldeanueva and Cervantes (2019), the sustainability strategies of companies confer competitive advantages and help create value, which helps explain the interest of companies in working with agencies that develop organizational performance measurement mechanisms (e.g., Dow Jones Sustainability Index, Carbon Disclosure Project, and Global Reporting Initiative) and instruments to disseminate sustainability initiatives such as sustainability reports, newsletters, social media, and websites.

Academic research on sustainability has increased considerably in the last decade, with published articles focused primarily on evaluating sustainability reports as a management tool, critical indicators, appropriate models, frequency of dissemination, and depth of information. Among the more relevant aspects of these studies is the link between CSR, ethics, and organizational reputation (Castaño Ramírez & Arias Sánchez, 2021; Chen et al., 2023; Jiménez-Yáñez & Fontrodona, 2022; Kim & Lee, 2020; Schröter et al., 2021; Sepúlveda et al., 2018; Shim & Kim, 2021).

Unsurprisingly, sustainability reports have gained considerable traction in the corporate world, likely because they are voluntary and subject to organizational guidelines (Acevedo & Piñero, 2019; Buitrago, 2021; Herrera et al., 2013; Hurtado-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Monfort & Mas, 2021; Semenova, 2023; Thijssens et al., 2016). While these reports are certainly a key communications tactic, they are neither the only nor the most important tactic available. In 009, the Conselho Empresarial Brasileiro para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável (Brazilian Corporate Council for Sustainable Development, CEBDS for its acronym in Portuguese) published the Communication and Sustainability Guide, which was inspired by the principle of the triple bottom line (Elkington, 1998). The guide established three dimensions of sustainability communications: information, change, and process, vital elements in communications management. Sustainability reports are clear examples of the information dimension, or what is known as sustainability communications. Its objectives are to seek empathy with strategic audiences by communicating what the company does, how it does it, and why. The second dimension is aimed at changing the behavior of the public through the promotion of dialogue, reflection, education, and even mobilization. In this case, it is seen as communications for sustainability. The dimension of the process focuses on interaction and construction of meaning, thus considering individuals as key participants who can inspire sustainability processes and help achieve their materialization in organizations with appropriate communications management.

Based on this distinction, it is not enough to keep the public informed about what the company does administratively and explain what behaviors are expected; it is also essential that this communication has meaning and authentic value so it can be internalized. From this perspective, the value of communications lies in creating a reciprocal connection with an organization to change the attitudes and behaviors of different stakeholders (García-Nieto et al., 2020). As suggested by Lattuada (2010), sustainability processes require the construction of a collective consciousness that creates shared meanings in the organizational environment. This can only occur with exchanges, shared experiences, and conversations that foster meaningful relationships with the public to promote social change. That is, it adds value to the community and increases the organization’s social capital, all while enhancing the effect of communications with stakeholders (Salnikova et al., 2022). For Godemann and Michelsen (2010), sustainability communications is a process of mutual understanding that shows concern for the future and development of society at different levels and contexts and in all types of national and regional settings to assess meaningful stakeholder engagement. A message is absorbed with greater intensity and affects the actions of individuals when they are inspired to act based on the knowledge received (Costa & Teodósio, 2011).

All this reflection leads to a more comprehensive look at communications and its strategic management, which establishes the global guidelines for the definition of a company’s central message and subsequent selection of the action plans that will allow a company to achieve the objectives established with its public (Madroñero & Capriotti, 2018).

Within this framework, this study applies the Communications and Sustainability Convergence Model by Durán and Mosquera (2016) to evaluate how both disciplines are manifested in companies in Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile. This was achieved through developing and administrating a survey based on the model with communications managers at 96 large companies in those three countries.

Communications and Sustainability Convergence Model: Theoretical underpinnings

Numerous studies address the contribution of communications in sustainability processes (e.g., Bartlett et al., 2007; Gill, 2015; Giraldo-Dávila & Maya-Franco, 2016; Goi & Yong, 2009; Molina et al., 2017; Roger-Monzó, 2022; Roper, 2012). However, these disciplines do not continually advance in a coordinated or coherent manner within organizations. A study conducted at large Brazilian and Ecuadorian companies by Durán and Ferrari (2018) showed that only 33 % of Brazil and 26 % of Ecuador keep their departments of communications and sustainability under the same management. Likewise, only 59 % and 66 % of surveyed communications professionals in Brazil and Ecuador, respectively, mention support for corporate social responsibility and sustainability as the most frequent functions of their departments.

Durán and Mosquera’s (2016) Communications and Sustainability Convergence Modelis based on three theories: Grunig and Hunt’s (2000) Public Relations Management Models, Garriga and Melé’s (2004) Paradigms of Social Responsibility, and Austin’s (2003) Continuum of Collaboration. With these theories as a base, the model establishes four contexts for companies based on their type of communications management and sustainability.

The first context is called organizations centered on business, which maintains the idea of philanthropic support and, in general, the adoption of a press agent model of communications. The second context describes organizations centered on accountability, where relations with the organizations’ public are transactional, and conversations are established to defend the organization’s interests. The communications model is that of public information, which maintains a one-way communications flow. The third context applies to organizations centered on public interests, whose orientation is based on the knowledge of the needs and aspirations of stakeholders. Communications are managed through a two-way asymmetrical model that collects feedback from different publics, allowing the company to achieve organizational objectives. The fourth and final context is that of organizations centered on the common good, guided by organizational values and a view of social responsibility based on recognizing that all corporate actions impact society. These organizations maintain a close and integrative collaborative relationship in which dialogues are established t in equal conditions, so a symmetrical two-way model of communications applies.

The model applied in the present study is based on the premise that the context that best describes an organization can be determined by evaluating five key variables that allude to observable communications and sustainability management practices, as established in the instrument published by Durán and Mosquera (2016).

In the field of communications, the key variables are as follows: the flow of information, communications objectives, communications strategies, profile of the communications professional, and corporate discourse. Regarding sustainability, the five analysis variables are as follows: conceptual line, type of support, planning and resources for social responsibility, planning for environmental preservation, and respect for human rights.

Thus, the study set out to answer the following research questions:

What context best describes the orientation of the organizations based on their communications practices regarding the flow of information, objectives, strategies, professional profiles, and discourse?

What context best describes the orientation of the organizations based on their sustainability practices regarding conceptual lines, types of support received, allotted resources for social responsibility, environmental planning, and level of importance given to human rights protections?

What is the level of alignment between the organizations’ communications and sustainability practices?

The Results section explains these variables and their use in the present study.

Materials and methods

Sample selection

This article derives from a more extensive quantitative study on the communications practices for sustainability in large companies in Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile. In determining the sample, the authors worked under the premise that larger organizations would have sufficient resources to establish management and sustainable development mechanisms. To build a sample of 100 companies, the authors took as a reference the 2018 business rankings published in highly prestigious specialized magazines on economics and business in each country: América Economía (Chile), Dinero (Colombia), and Ekos (Ecuador). The magazines prepared the rankings based on the companies’ income and profit reports.

Once the sample was built, the next step was to create a database of critical communications professionals at each company, including managers and directors. To secure participation, the researchers established contact with the companies via email and phone to obtain contact information on the professionals, explain the study’s objectives and guarantee confidentiality. In total, ninety-six companies agreed to participate in the study: Ecuador (n = 24), Colombia (n = 34), and Chile (n = 38).

Instrument implementation

The Survio platform served as a medium to create an online survey based on Durán and Mosquera’s (2016) instrument to identify sustainability and communications strategies in companies. The survey was designed to include the dimensions of communications and sustainability, each with the five variables mentioned in the theoretical framework. In each of the five variables, four options or categories with descriptions were presented so the respondent could weigh, on a 10-point scale, those that best described the management of their organization. The scores assigned by the respondents were then added and averaged in the analysis phase to obtain data for each country.

Results

As a descriptive study, instead of generalizing the results, the objective was to elucidate the trends of a group of companies, compare the practices of the three countries and identify those that could be modified to favor further evolution in the sustainability process.

Communications

Regarding the practice of communication, the results are as follows:

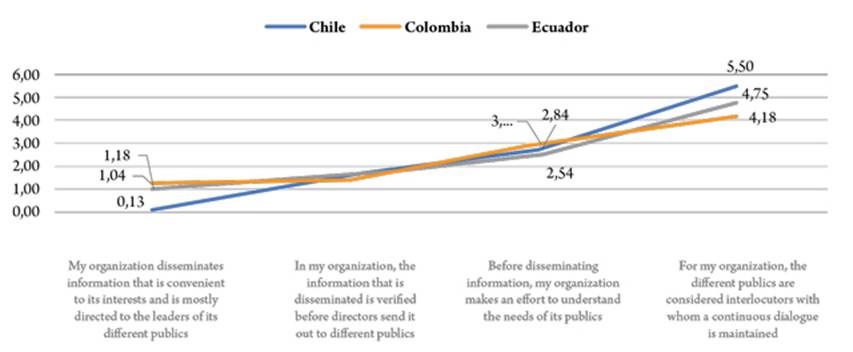

a. The flow of information. Based on the public relations model by Grunig and Hunt (2000), this variable observes whether communication flows in a one-way or two-way direction and whether it is symmetrical or asymmetrical. Respondents highlighted the following answers concerning the flow of information within their organizations (see Figure 1).

According to the responses, in Chile (5.50) and to a lesser degree in Ecuador (4.75) and Colombia (4.18), most respondents believe their organization considers different audiences as interlocutors with whom they maintain a continuous dialogue with a symmetrical and two-way flow. This type of relationship allows organizations to discern their demands and expectations since the success or failure of the company depends on their satisfaction (Apolo et al., 2017).

The number of those who consider that efforts are made in their organizations to understand the needs and interests of their audiences is lower: Colombia (3.09), Chile (2.84), and Ecuador (2.54). In light of the model, the data reflect that, although there is more strategic management regarding the flow of information, an essential and one-way approach still exists. This coincides with Capriotti et al’s (2021)) findings, who found that a business tends to maintain a monologue even through digital means.

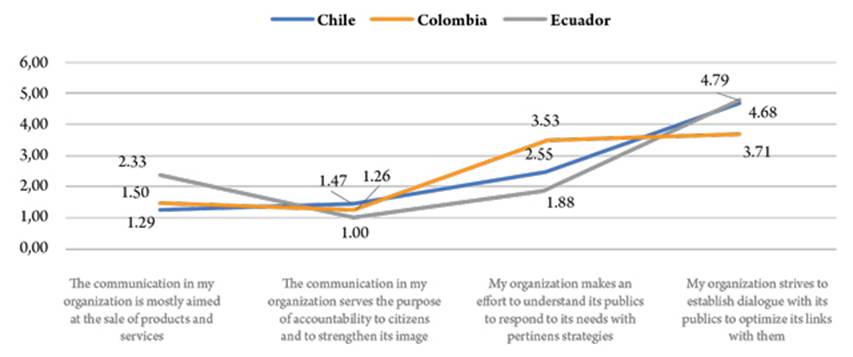

b. Communication objectives. This variable represents the nature of communications objectives in the organization and the type of relationship with its stakeholders (see Figure 2)

In Ecuador, the numbers show a considerable difference between those who consider that their organizations seek to establish a dialogue with stakeholders to optimize ties with them (4.79) and those who indicate that their companies do so only to respond to their needs with specific strategies (1.88). Something similar occurs in Chile (4.68 versus 2.75). In Colombia, however, these two responses reached a somewhat similar score (3.71 compared to 3.53).

From the point of view of the model, the search for a direct dialogue with the public is pursued through various means, while efforts to understand the public are accomplished with research strategies such as diagnoses of organizational climate, communication audits, market studies, corporate image analysis, and others; these seem to be more frequent practices in Colombia than in other countries.

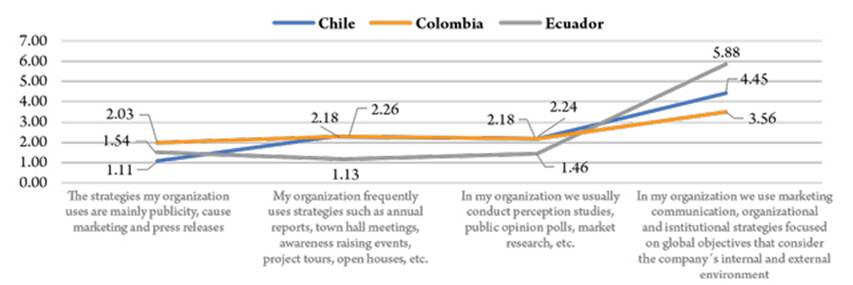

c. Communications strategies. As a study variable, communications strategies are evaluated according to the direction and approach that the set of communication activities carried out in the organization (Cooper, 2006; Durán & Mosquera, 2016; Ferré & Ferré, 1996; Pérez, 2005; Matilla, 2009). Developing communications strategies aligned with organizations’ needs enables them to create, improve or maintain their corporate identity, image, and reputation (Apolo et al., 2017) ; see Figure 3).

In Ecuador (5.88), Chile (4.45), and Colombia (3.56), executives maintain that their companies simultaneously use diverse strategies that take into account internal and external environments. In Chile, the most traditional strategies, such as press releases, advertising, and cause marketing, reached an average of 1.11, which means that very few companies recognize them as important tactics. However, they are more frequent in Ecuador (1.54) and Colombia (2.03).

The use of resources such as management reports, public assemblies, awareness events, tours of projects and facilities, and open houses o tained a reasonably low score in Ecuador (1.13) but not so much in Colombia (2.18) and Chile (2.26). Something similar occurs with the tactics that seek to investigate the interests of the public, such as image, market, and public opinion studies. In Ecuador, the scores reached an average of 1.46, in Colombia, 2.24, and in Chile, 2.18.

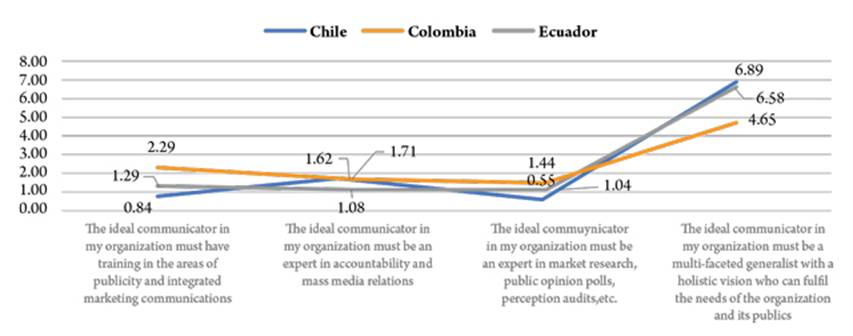

d. Profile of the communications professional. This variable addresses the training and skills the communications professional must develop in each context. Cubillos (2010) asserts that these competencies are becoming more demanding and must respond to a market that requires professionals “with more human and ethical traits focused on cognitive and technical skills of the discipline.” In other words, according to Costa (2012, p. 16), a multi-talented professional with a “global, holistic view of parts and details, as well as a systemic view of operations as a whole” (see Figure 4).

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 4 Profile of the communications professional in Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile.

In Chile (6.89) and Ecuador (6.58), and with a notable difference from Colombia (4.65), the majority of responses favor a profile as someone responsible for all communications initiatives of significant responsibility, with a holistic and articulating vision of the organization’s objectives in communication management. Meanwhile, the lowest score in the three cases (1.44 in Colombia, 1.04 in Ecuador, and just 0.55 in Chile) reflects a mindset that prefers an expert in market research, public opinion polls, and reputation audits.

In Colombia (2.29), the criterion that the ideal profile of a communications professional should include knowledge of advertising and integrated communications is more frequent than in other countries (Ecuador: 1.29; Chile: 0.84). Likewise, the idea of an expert in accountability and media relations had a relatively low score in Ecuador (1.08) but not so much in Colombia (1.62 and Chile 1.71).

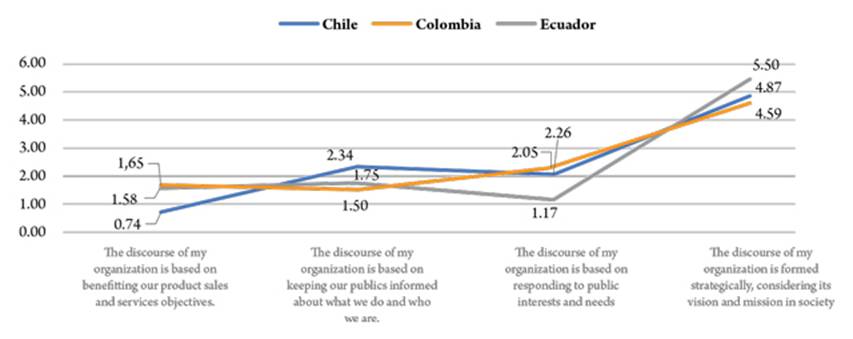

e. Corporate discourse. As per the model of Grunig and Hunt (2000), the background of the content of the message is what allows one to discern the discursive approach of the organization; that is, what the company says about itself or the environment. Thus, it could emphasize disseminating a product or service or informing the public about institutional activities beyond the products. The most complex level implies discourse management that ranges from responding to the needs of the public of interest to a more strategic discourse based on the vision and corporate philosophy of the organization (see Figure 5).

In this variable, Ecuador (5.50) stands out as the country where most communications professionals believe their organizations have a strategic discourse that considers the vision and mission of the organization, followed by Chile (4.87) and then Colombia (4.89). The second-highest average score among Chileans (2.34) and Ecuadorians (1.75) is a business discourse that keeps stakeholders informed of the organizations’ actions. On the other hand, for Colombians, the second-highest score (2.26) reflected a focus on the interests and needs of the public.

In Chile, there were very few responses (0.74) indicating that the corporate discourse has the primary function of supporting business management. While in Ecuador and Colombia, this option was also minor (1.58 and 1.65, respectively), it was more significant than in Chile.

Sustainability

As in the dimension of communications, five variables are analyzed under the sustainability dimension to identify the context to which each organization belongs.

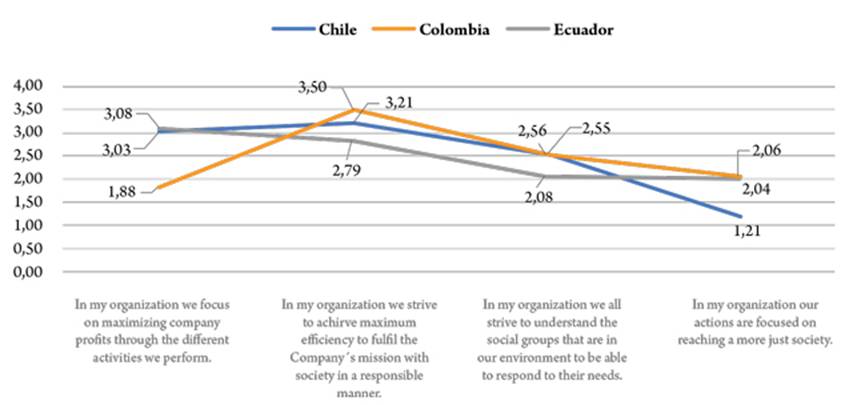

a. Conceptual line. This variable corresponds to the theoretical approach that organizations use or validate in the design and execution of their sustainability strategies. In principle, they follow Garriga and Melé’s (2004) proposal, according to which it is possible to distinguish, hierarchically or evolutionarily, between instrumental, political, integrative, and ethical perspectives. The survey presented options that ranged from an interest focused on profit maximization to the search for a fairer society, also known as the Common Good (see Figure 6).

The preferred option for communications professionals from Colombia (3.50) and Chile (3.21) reflects the notion that everyone in their organization seeks the greatest efficiency to fulfill the company’s mission in society responsibly. While in Ecuador, the preferred option (3.08) reflected a focus on maximizing company profits through different activities-which was also scored similarly in Chile (3.03)-, Colombia showed a much lower score (1.88).

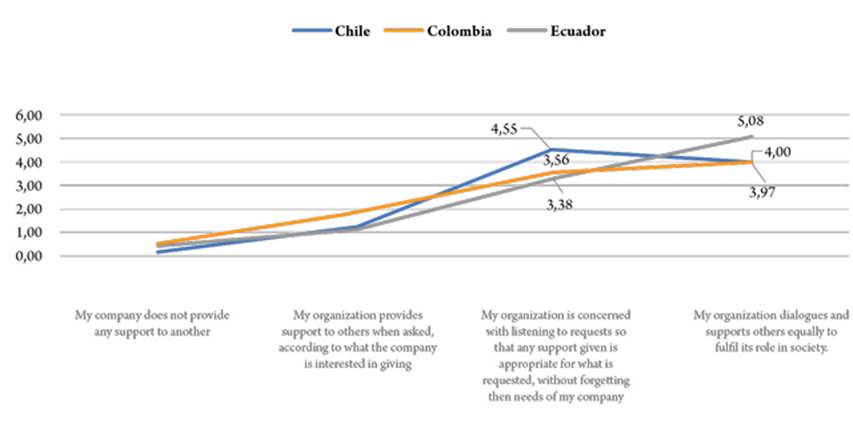

b. Type of support. This variable is based on Austin’s (2003) proposal that classifies how companies are linked with public and non-industrial organizations (NGOs, foundations, educational entities) through three stages of relationships (philanthropic, transactional, and integrative) due to their flexibility and adaptive character. These stages comprise a “collaboration continuum” (see Figure 7).

Ecuadorian communications executives declared more frequently (5.08) that their organization’s dialogue and collaborate on equal terms with several others to fulfill their role in society, followed by Colombians (4.00) and Chileans (3.97). In the case of Chile, the most frequent response was that the organization listens when support is requested so that it is adequate to what the applicant needs, but without disregarding the company’s needs.

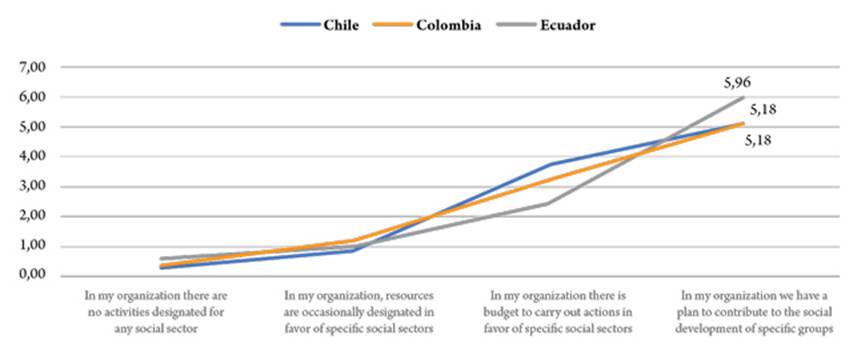

c. Planning and resources for social responsibility. This variable refers to the strategies and mobilization of resources to recognize and satisfy social needs. Considering the current importance of community relations and the positive impact they can have on business activity (Grayson, 2005; Zúñiga y Postigo, 2013), it is not uncommon for social responsibility strategies to gradually mutate from philanthropy to deeper stakeholder engagement (Matus, 2018) (see Figure 8).

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 8 Planning and resources for social responsibility in Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile.

Across all three countries, the majority of responses pointed to the existence of planning to contribute to the social development of certain groups, with scores of 5.18 in Chile and Colombia and 5.16 in Ecuador. The incidence of responses that stated activities in favor of the social sector are not contemplated or done occasionally was insignificant.

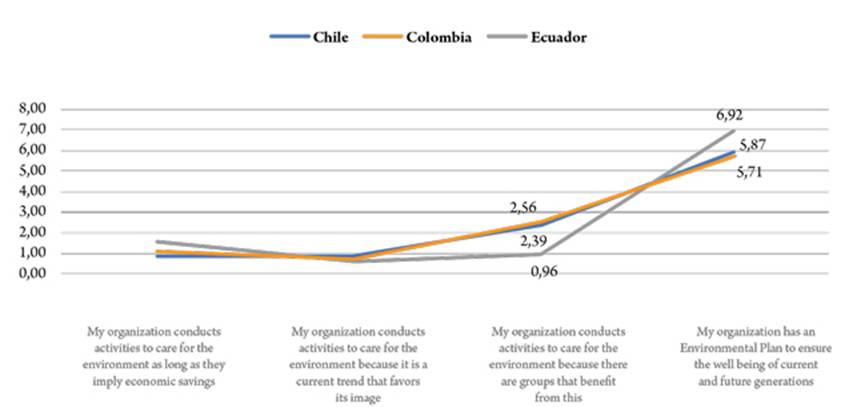

d. Planning of environmental preservation. Zbuchea and Pînzaru (2017) warn that organizations’ size and financial capabilities significantly affect their ability to design and implement environmental preservation strategies. Likewise, Bosch-Badia et al. (2020) question the efficiency of such projects since they are customarily evaluated exclusively considering their contribution to the corporate image/reputation and not to the creation of net value for the company or society. Figure 9 shows the surveyed companies’ results concerning their environmental preservation approaches.

In this regard, the majority response is that organizations have an environmental plan to ensure the well-being of current and future generations (Ecuador: 6.92, Chile: 5.87, and Colombia: 5.71). Other respondents indicated that their organization takes actions to preserve the environment because human groups benefit from these actions (Colombia: 2.56; Chile: 2.39, and less in Ecuador, with 0.96). It is worth highlighting that more communications professionals in all three countries say their companies carry out environmental preservation initiatives as long as they imply economic savings rather than because it is a current trend that favors the organization’s corporate image.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 9 Planning of environmental preservation in Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile.

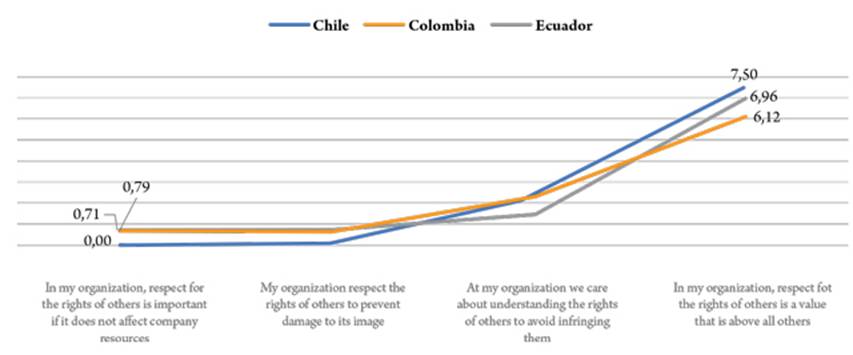

e. Respect for the rights of others. This variable values respectful conduct with workers, competitors, consumers, and other stakeholder groups. Traditionally, it refers to the link between sustainability and human rights, especially defended by the United Nations (see, for example, UN Global Compact, 2018), and to aid in the comprehension of the concept of human rights from a contemporary business perspective (Eizenberg & Jabareen, 2017) (see Figure 10).

Chile reported the highest average score (7.50) in this variable, followed by Ecuador (6.96) and Colombia (6.12). At the other extreme, not a single respondent in Chile reports that respect for the rights of others is essential so long as it does not affect company resources or harm the company’s reputation. While Ecuador and Colombia report slightly higher scores than Chile, these are still relatively low (0.71 and 0.79, respectively).

Discussion

Regarding the first research question, which focused on describing the context of the organization’s communications management practices, the survey results show a marked inclination towards an ideal scenario: the Common Good.

In communications work, symmetrical, two-way communication flows are most notable, which allow constant feedback with key stake-holders. There is also a tendency towards work aimed at maintaining a permanent dialogue with the public.

Company strategies have a global vision and cover the internal and external environments of the organization. The organization’s discourse is proposed strategically and considers its corporate philosophy; that is, its mission, vision, and values.

The profile of the ideal communications professional is described as a generalist and versatile executive with a holistic vision who addresses the organization’s interests and those of its audiences (something highly valued by the literature, as in Costa, 2015).

As for the second research question, which aimed to describe the context of the organization’s sustainability management practices, a similar inclination toward the Common Good was found, with some minor discrepancies. Companies claim they dialogue and collaborate on equal terms with other entities to fulfill their societal role and have social development and environmental plans to ensure the well-being of current and future generations. Fostering respectful conduct with workers, competitors, consumers, and other stakeholder groups is also prevalent.

Regarding the third research question, which seeks to analyze the degree of alignment of the organization’s communications and sustainability practices, it was found that the only sustainability management variable that does not fit within the context of organizations centered on the Common Good is, paradoxically, the conceptual line or, in other words, the company’s conception of sustainability. As noted previously, according to Garriga and Melé (2004), this aspect guides management and marks the vocation of the company’s members. However, the responses of the communications professionals surveyed reflected an inclination towards contexts centered on accountability and business. Thus, they consider sustainability more related to fulfilling the organizational mission than contributing to achieving a fairer society.

The raw data alone cannot explain this particularity; in principle, the apparent contradiction between the companies’ strategies and operations can be seen as a point that merits criticism. However, it can also be assumed that this difference is due to a common bias in the business world, where sustainability is seen as a new way of doing business and, due to its connection with social needs and expectations, as a means of increasing competitiveness (e.g., Eweje, 2011). In fact, this is the central argument of much of the literature on corporate responsibility (e.g., AccountAbility, 2018; Burke, 1999; Elkington, 1998; Kotler & Lee, 2005; Porter & Kramer, 2011).

Another possible interpretation for this uniqueness is that the conceptualization of sustainability by companies remains dispersed. This coincides with the findings of several authors (e.g., Hurtado-Jaramillo et al., 2016; Montiel & Delago-Ceballos, 2014; Paul, 2008; Sarvaiya & Wu, 2014) who suggest that the diversity of terms used to refer to the subject (e.g., corporate social responsibility, corporate sustainability, sustainability, corporate social performance), and the consequent lack of specificity of these concepts make it difficult to implement, manage and evaluate company’s performance in this matter.

On the other hand, when comparing the data from the three countries, common trends can be identified. The data gathered from the communications professionals surveyed show a greater orientation toward the ideal scenario known as the context of organizations centered on the Common Good (as per the Communications and Sustainability Convergence Model) and a minimal orientation towards the business, which is considered a less evolved scenario as it typically involves one-way communication and a conception of social responsibility as a competitive advantage.

Conclusions and implications for future research

The average, large-sized company in Ecuador, Colombia, and Chile manages its communications and sustainability processes with a focus that, according to what is suggested by the Communications and Sustainability Convergence Model, leans toward the Common Good and the harmonious development of society. This shows a vocation for sustainable development in the broadest sense in large companies, that is, against all traditional prejudices of companies using sustainability as a tool to improve their corporate image, also known as greenwashing (Cooper, 2015; Hallama et al., 2011; Kassinis & Panayiotou, 2017; Kim & Lyon, 2014), it is possible to observe communications management that aims to strengthen the sustainability of companies and society in general. However, the lack of consensus concerning the concept of sustainability and clarity of the role of communications points to a need for academia to insist that communications fulfill its multiple roles beyond supporting the production and commercialization of goods and services. Further, it must transcend mechanical approaches and recognize its integral, comprehensive, and integrative dynamics with a multidimensional approach to satisfy the needs and motivations of various stakeholders (Benavides & Cortés, 2018). Future research of a qualitative nature may provide greater clarity on the causes and effects of communications management on sustainability in Latin American corporations. Likewise, future research must identify the areas with tremendous potential for the nexus between public and private agendas and the degree to which communications drive advancement toward the respective SDGs that companies have declared in their sustainability policies.