Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

International Journal of Psychological Research

Print version ISSN 2011-2084

int.j.psychol.res. vol.9 no.1 Medellín Jan./June 2016

Psychometric properties of the Attitudes Toward Gay men scale in Argentinian context: The influence of sex, authoritarianism, and social dominance orientation

Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de Actitudes hacia la Homosexualidad Masculina en el contexto argentino: La influencia del sexo, el autoritarismo y la orientación a la dominancia

Edgardo Etchezahara,b,e,* Joaquín Ungarettia,b Vicente Prado Gaseód and Silvina Brusinoc,e

a CIIPME Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

b Universidad Nacional de Lomas de Zamora, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

c CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

d Universidad Europea de Valencia, Valencia, España.

e Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina.

Corresponding author: Edgardo Etchezahar, CIIPME, Universidad de Buenos Arires, Buenos Arires, Argentina. Email address: edgardoetchezahar@psi.uba.ar

Article history: Received: 01-06-2015 Revised: 28-10-2015 Accepted: 27-11-2015

ABSTRACT

Even though prejudice toward male homosexuality is one of the main reasons for discrimination in Argentina, there is no valid measure to assess it. The aim of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the Attitudes Toward Gay Men Scale (ATG) and to examine the influence of sex, right wing authoritarianism, and social dominance orientation on anti-gay attitudes. Data were collected with a convenience sample of 436 undergraduate students from University of Buenos Aires. Analysis of the data showed adequate psychometric properties for the ATG Scale and the moderating effect of sex, right wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on anti-gay attitudes. Implications of these findings were discussed.

Key words: Homosexuality, prejudice, sex, authoritarianism, dominance.

RESUMEN

A pesar de que el prejuicio hacia la homosexualidad masculina constituye una de las principales causas de discriminación en Argentina, no existen instrumentos válidos para evaluar dicho constructo. El objetivo del presente trabajo fue analizar las propiedades psicométricas de la escala de Actitudes hacia la Homosexualidad Masculina (ATG) y examinar la influencia del sexo de los participantes, el autoritarismo del ala de derechas y la orientación a la dominancia social en las actitudes anti-gay. La muestra fue intencional y estuvo compuesta por 436 estudiantes de la Universidad de Buenos Aires. El análisis de los datos indicó adecuadas propiedades psicométricas para la escala ATG, así como el efecto moderador del sexo en las relaciones entre el autoritarismo del ala de derechas y la orientación a la dominancia social en las actitudes anti-gay. Se discuten las implicancias del presente estudio.

Palabras clave: Homosexualidad, prejuicio, sexo, autoritarismo, dominancia.

1. INTRODUCTION

It is widely accepted that homosexuality in Argentina, as in many other Latin American nations, has had a negative connotation throughout history (Meccia, 2003). Despite the approval of an amendment to the Civil Marriage law, allowing for same-sex marriage and child adoption, in 2012 a total of 1500 sex discrimination complaints were registered by the Argentine Homosexual Community (Paradiso Sotile, 2013). This appears to indicate that prejudice and discrimination against sexual minorities still exists in Argentina.

Research on attitudes toward homosexuality from a psychological perspective started in 1972, when Weinberg criticized the traditional conception of homosexuality as an individual pathology that harms society. On this basis, the author developed the concept of homophobia to refer to an extreme and irrational fear and rejection to stay indoors with homosexuals. Despite Weinberg's (1972) important contributions to understanding the rejection of homosexuality, the empirical assessment developed by Weinberg had several limitations. Primarily, the fact that hostility towards homosexuals was understood in terms of a phobia, emphasized fear as a causal factor of negative attitudes. However, Shields and Harriman (1984) argued that although this may be true for some individuals, the fear levels associated with homophobia were not comparable to those of other phobias. As a result, Lottes and Grollman (2010) states that as with homophobia, definitions of homonegativity are not consistent because some focus only on a cognitive domain, and others include both affective and cognitive aspects. Nevertheless, as suggested by Moreno, Herazo, Oviedo and Campo-Arias (2015), considering homonegativity would be an important way to understand the reason for its prevalence.

As an alternative to these conceptualizations, Herek (1988) argued that negative heterosexual reactions toward sexual minorities cannot be regarded as an individual pathological trait, but as the product of internalizing a sexual stigma: "the negative connotation that society as a whole gives to all those non-heterosexual behaviours, identities, relationships and communities" (Herek, 2009, p. 66). For Herek, negative attitudes toward homosexuality have not only a psychological basis, but also a sociocultural basis supported by collective constructions built on the supposed inferiority of sexual minorities. As a result of the internalization of sexual stigma, heterosexual individuals project feelings toward minorities in the form of negative attitudes that constitute sexual prejudice (Herek, 2009). If prejudice is defined as a negative attitude toward a group or an individual belonging to a particular group (Duckitt, 1992; Fiske, 2009), sexual prejudice refers to all those negative attitudes directed toward an individual for belonging to a non-heterosexual group (Herek, 2009).

In order to assess individual differences in sexual prejudice, Herek (1988) developed the Attitudes Toward Lesbians and Gay Men Scale (ATLG). The ATLG consists of 20 items divided into two subscales with ten items each: Attitudes Toward Gay Men (ATG) and Attitudes Toward Lesbians (ATL). After being administered to a sample of 280 college students, the psychometric properties for the total scale (ATLG: a = .90) and for every dimension (ATL: a = .77; ATG: a = .89) were adequate. Despite these measures were widely used for the assessment of sexual prejudice in different contexts (Stoever & Morera, 2007; Wu & Kwok, 2012), including Spanish speakers (Barrientos & Cárdenas, 2012; Moral de la Rubia & Valle de la O, 2011), there are no studies about prejudice toward gay men in Argentina.

The ATG scale, allows researchers to analyze the relationship of sexual prejudice with other related constructs as the centrality of religion and political orientation. The centrality of religion, defined as the degree to which precepts proposed by a particular religion guide a person's life (Cárdenas & Barrientos, 2008), has been found to predict anti-gay behaviour (e.g., rejection of gay civil marriage, opposition to antidiscrimination laws) (Bassett, Kirnan, Hill, & Schultz, 2005). Moreover, it has been shown that political orientation is also related to sexual prejudice (see DeRosa & Kochurka, 2006), particularly with right-wing or conservative ideologies, that consider homosexuality as a perversion hindering the development of a traditional family (Harper, 2007). Finally, several studies also suggested that sex is one of the strongest predictors of attitudes toward homosexuals, and that heterosexual men tend to be more homophobic than women (Cárdenas & Barrientos, 2008; Herek, 2000). For instance, Kite and Whitley (1996) confirmed such a difference in a meta-analysis of 109 studies addressing the relationship between the participants' sex and their attitudes toward lesbians and gay men.

Despite the importance of the centrality of religion, political orientation and sex to understand sexual prejudice, one of the main controversies coming from the field of psychology has been whether social attitudes such as right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation explain different forms of prejudice, particularly sexual prejudice (Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt, 2010).

Right-wing authoritarianism is defined as the covariance of three attitudinal clusters: authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, and conventionalism (Altemeyer, 1981, 1998). The first cluster refers to the tendency to submit to the authorities as established and legitimated in one's society; the second assesses the predisposition to hostility toward individuals and groups seen as potential threats to the social order; and the third concerns the general acceptance of social conventions (Altemeyer, 1981, 1996). Thus, people with high levels of right-wing authoritarianism tend to express negative attitudes toward those who deviate from the values and ways of life of their own group (Altemeyer, 1998) and are perceived as threats to traditional norms and values (Cohrs & Asbrock, 2009; Duckitt & Sibley, 2010).

Moreover, given that sexual prejudice is based on cultural stigma, status and power differences between groups are reinforced. This phenomenon legitimises negative representations that elicit higher levels of prejudice and discrimination in order to sustain the inferior status of minorities. Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, and Malle (1994) posited a social dominance orientation, as a general attitudinal orientation toward intergroup relations that reflects the degree to which individuals prefer hierarchical relationships over egalitarian ones, and the extent to which they wish to maintain the superiority of their own group over the outgroup. Due to this anti-egalitarian component, individuals with high levels of social dominance orientation tend to be more prejudiced against homosexuality considered as a minority social group targeted for domination (Kilianski, 2003; Whitley & Lee, 2000).

Hence, the main objectives of this study were: firstly, to analyze the psychometric properties of the Attitudes Toward Gay (ATG) men in Argentinean population and, secondly, to examine the sex's moderator effect on predicting ATG relations to right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation.

Hypothesis 1: Attitudes toward male homosexuality are explained by differences in right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation.

Hypothesis 2: There is a moderator effect of sex in the prediction of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on attitudes toward gays.

2. METHOD

2.1 Participants

The present study involved a sample of 436 university students from Buenos Aires. Participants were between 18 and 42 years old. The mean age of the entire sample was 22.4 (SD = 3.21), 54.3% was female (n = 237) and 45.7% male (n = 199). Also, 6.19% (n = 27) belongs to the lower middle class, 80.50% (n = 351) to middle and 13.31% (n = 58) to upper middle.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Attitudes Toward Gay Men scale

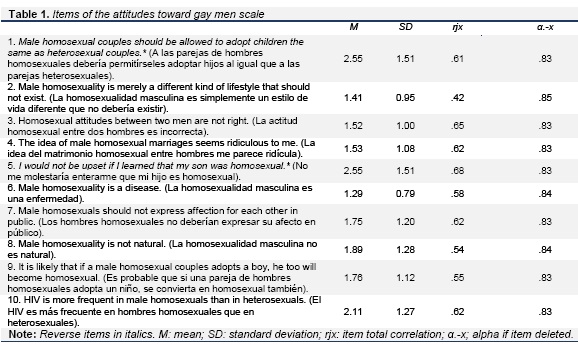

Ten items from the original Herek (1988) ATG scale, translated into Spanish, were evaluated (see Table 1). A five-point Likert-type scale ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree" was used. Higher scores address higher levels of negative attitudes toward gay men.

2.2.2 Right-wing Authoritarianism scale

An abbreviated version (six items) of the original right-wing authoritarianism scale (Altemeyer, 1996) was used, adapted and validated to the Argentine context (Etchezahar, 2012) with a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree". Higher scores address higher levels of authoritarianism. The internal consistency (a = .92) and the construct validity (.98 < CFI < .99; .04 < RMSEA < .07) results, were adequate.

2.2.3 Social Dominance Orientation

A version of the original scale (Pratto, et al., 1994), adapted and validated to the Argentine context with a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree", was used (Etchezahar, Prado-Gascó, Jaume & Brussino, 2014). The scale's ten items are grouped in two dimensions: Group Dominance and Opposition to Equality, which together conform the social dominance orientation construct. Higher scores address higher social dominance orientation levels. The internal consistency (a = .82) and the construct validity (CFI = .94; RMSEA = .07) of the scale, was adequate.

2.2.4 Ideological-political Self-positioning Scale

An adapted version of the one item Rodríguez, Sabucedo, and Costa (1993) scale, was employed: "When talking about politics, people speak of the left and right: according to a scale from 1 to 5, being 1 extreme right and 5 extreme left, where would you place yourself?".

2.2.5 Centrality of Religion.

One question extracted from the studies by the Centre for Sociological Research in Spain (CIS) was included: "In your opinion, what role does religion play in your life?" The answer was a continuum ranging from 1 = I am not interested by religion, to 5 = Religion is central in my life.

2.3 Procedure

The subjects were invited to participate in the study voluntarily, requesting their informed consent. Furthermore, they were informed that the data derived from this research would be used only for academic and scientific purposes under the Argentinean National Law 25.326 that protects personal data. The international methodological standards recommended by the International Test Commission (ITC) when adapting an instrument to a foreign language (Hambleton, Merenda, & Spielberger, 2005) were followed for the attitude toward gay scale validation, including back translation process (English- Spanish- English) by two bilingual researchers.

2.4 Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 20.0 (Lizasoain, & Joaristi, 2003) and EQS 6.1 (Bentler, 1995). First, descriptive statistics for every item were calculated, followed by the analysis of the scale's reliability and validity. Subsequently, the predictive power of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation over attitude toward gay men was examined by developing a path analysis. Finally, the sex's moderator effect on predicting attitude toward gay men relations with right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation was studied by running t-test analyses of the variables under study and by using SEM.

3. RESULTS

3.1 ATG Item Analysis and Internal Consistency of the Scale

First, the ten items of the ATG scale were analysed. Final item wordings, mean (M), standard deviation (SD), item-total correlation (rjx) and Cronbach's Alpha if item deleted (a.-x) are displayed in Table 1 for every item.

In general, every item contributed to the overall scale with a relatively high correlation (.42 < rjx < .68) and reliability did not improve if an item is removed (Hair, Anderson, Thatam, & Black, 2006). The internal consistency of the ATG scale's adaptation was examined by means of Cronbach's Alpha, which resulted in adequate values (α = .85).

3.2 Validity Analysis

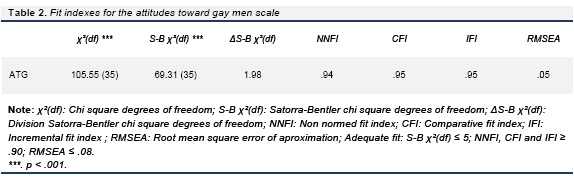

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were performed using the 10 items of the ATG scale. The adequacy of the sample was evaluated using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test (KMO = .912) and Bartlett's sphericity test (p < .001). Here, using the mean component analyses, an EFA was calculated with Varimax rotation. The obtained model consisted of a single dimension explaining 45.72% of the variance. Afterwards, a CFA was conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation with Satorra-Bentler's robust correction (SB) (Satorra, 2002). Information regarding the model fit is displayed in Table 2.

Results indicated that the proposed model seems to adequately fit the data, suggesting the instrument shows acceptable internal validity.

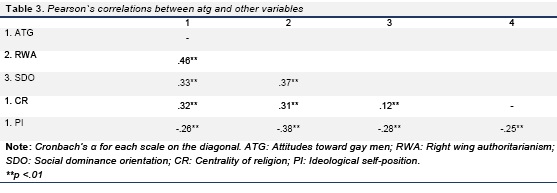

As suggested by the literature, relations between ATG and other constructs were examined. Hence, Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated for ATG, RWA, SDO, CR and PI (Table 3).

As expected, results indicate a positive and significant association between ATG and RWA (r = .46; p < .01), SDO (r = .33; p < .01) and RC (r = .32; p < .01); while PI (r = -.26; p < .01) presents a negative association.

3.3 Influence of RWA and SDO over ATG

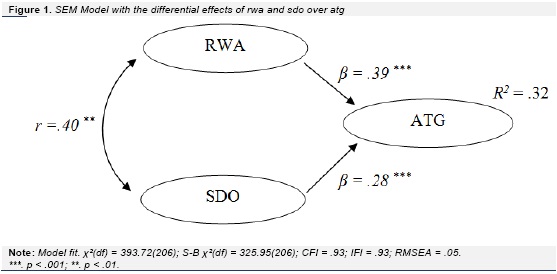

Here, the extent to which RWA and SDO have the ability to predict ATG values was tested. To that end, a SEM model was developed using the items from different constructs as indicators (Figure 1).

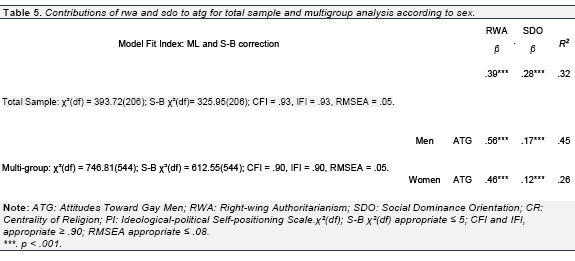

The proposed model presents adequate fit indexes. Although both variables seem to predict ATG, the contribution of RWA seems to be higher (β = .39; p < .001) than SDO (β = .28; p < .001).

3.4 Sex's moderator effect on predicting ATG relations to RWA and SDO

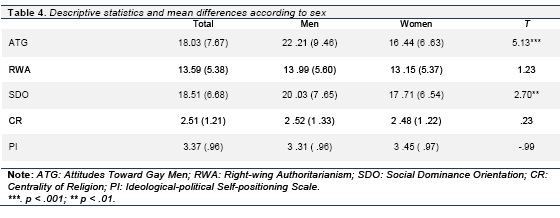

Finally, the moderator effect of sex on predicting relations between ATG, RWA and SDO was evaluated. Table 4 shows the descriptive results and mean differences (t-tests).

There were statistically significant differences between men and women regarding sexual prejudice and SDO, with higher values found in men. Nevertheless, no statistically significant differences were found regarding RWA, CR or PI.

Further analysis of the effect of sex on predicting causal relations between RWA and SDO over ATG is possible by means of a multi-group model (Table 5).

According to the results, sex seems to have a moderating effect on predicting the influence of RWA and SDO over ATG. In men RWA (p = .56; p <.001) and SDO (p = .17; p < .001) predicts 45% of the variance of ATG; while for women, these variables (RWA: p = .46, SDO: p = .12; p < .001) predict 26% of the ATG variance.

4. DISCUSSION

The items for the ATG scale considered here are different to those from other Spanish versions (Barrientos & Cárdenas, 2012). Results indicated that every item seems to contribute adequately to the overall scale and the ten-item structure replicates Herek's original version (1988). In addition, the reliability analysis was appropriate, similar to the results obtained in the original version (Herek, 1988) and versions adapted to other Spanish-speaking contexts (Barrientos & Cárdenas, 2012; Cárdenas & Barrientos, 2008; Moral de la Rubia & Valle de la O, 2011). Here, the results of the validation process of the ATG using CFA indicates that the model with better psychometric properties corresponds to 10 items grouped into a single factor. The same factor solution was found by Stoever and Morera (2007) after contrasting four models by CFA.

As shown by Cardenas and Barrientos (2008) and by Herek (1988), positive correlations between prejudice toward gay men and centrality of religion were observed. These results reflect that in Argentina, religion in general and Catholicism in particular still have a leading role not only in people's lives, but also in political decisions (DeRosa & Kochurka, 2006). In addition, as shown by DeRosa and Kochurka (2006), participants' ideological self-positioning was strongly associated with prejudice towards male homosexuality, featuring higher prejudice levels in right-wing rather than left-wing supporters.

In line with previous studies (Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt, 2010), prejudice toward male homosexuality was explained by differences in right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. However, it was mainly explained by differences in right-wing authoritarianism and less by those in social dominance orientation. These could be justified in heterosexuals desire to maintain traditional conservative values (e.g. gender roles, traditional family structure) trough negative attitudes toward homosexuals, who are perceived not only as a threatening and transgressive outgroup, but also as a minority group challenging the established status quo (Duckitt & Sibley, 2010).

Finally, as pointed out by several studies (Barrientos & Cárdenas, 2012; Cardenas & Barrientos, 2008; Herek, 1988, 2000) men tend to present higher levels of prejudice towards gay men than women. Additionally, as suggested by previous studies (Barrientos & Cárdenas, 2012), the moderating effect of sex on predicting prejudice towards gay men relations to social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism through SEM was tested. The results pointed out significant differences in the predictive power of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation trough attitudes toward gay between men and women. These differences suggest that traditional gender roles in Argentina still represent a value that allows heterosexual men to assert their masculinity (Vega, 2007). As a consequence, abandoning this value could threaten male dominance and therefore it's privileged status (Pratto et al., 1994).

One of the main contributions of this research is to provide a valid measure to assess prejudice toward homosexuals in Argentina and to test the role of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation in its prediction. In addition, this study represents a first approach to understanding the moderating effect of sex on prejudice and its prediction.

For future research on the ATG scale in the Argentine context, we suggest to examine the role that social desirability has over prejudice toward gay men considering some implicit measures of prejudice. It would also be recommended to assess whether differences by sex and differences between right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation when explaining ATG, remain when studying Attitude Toward Lesbian. Finally, the fact whether prejudice toward male homosexuality is modulated by other ideological variables not included in this work must be considered.

5. REFERENCES

Altemeyer, B. (1981) Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1996) The authoritarian specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1998) The other "authoritarian personality". En M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Pp. 47-92). [ Links ]

San Diego, CA: Academic. Barrientos, J., & Cárdenas, M. (2012) A confirmatory factor analysis of the Spanish Version of The Attitudes Towards Lesbians and Gay Men (ATLG) Measure. Universitas Psychologica, 11(2), 561-568. [ Links ]

Bassett, R. L., Kirnan, R., Hill, M., & Schultz, A. (2005): Validating the sexual orientation and practices scale. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 24(2), 165-175. [ Links ]

Bentler, P. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M., & Barrientos, J. (2008) The Attitudes Towards Lesbians and Gay Men Scale (ATLG): Adaptation and Testing the Reliability and Validity in Chile. Journal of Sex Research, 45(2), 140-149. [ Links ]

Cohrs, J. C., & Asbrock, F. (2009) Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and ethnic prejudice against threatening and competitive groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 270-289. [ Links ]

DeRosa, N., & Kochurka, K. (2006) Implement culturally competent healthcare in your workplace. Nursing Management, 37(10), 18-26. [ Links ]

Duckitt, J. (1992) The Social Psychology of Prejudice. NY: Praeger. [ Links ]

Duckitt, J. (2010) A Tripartite Approach to Right-Wing Authoritarianism: The Authoritarianism -Conservatism - Traditionalism Model. Political Psychology, 31(5), 685-715. [ Links ]

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2010) Personality, Ideology, Prejudice, and Politics: A Dual-Process Motivational Model. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1861-1894. [ Links ]

Etchezahar, E. (2012) Las dimensiones del autoritarismo: Análisis de la escala de autoritarismo del ala de derechas (RWA) en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Revista Psicología Política, 12(25), 591-603. [ Links ]

Etchezahar, E., Prado-Gascó, V., Jaume, L., & Brussino, S. (2014) Validación argentina de la escala de Orientación a la Dominancia Social (SDO). Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 46(1), 35-43. [ Links ]

Fiske, S. T. (2009) Social Beings: Core Motives in Social Psychology. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006) Multivariate Data Analysis. New Jersey: Pearson. [ Links ]

Hambleton, R. K., Merenda, P. F., & Spielberger, C. D. (2005) Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Harper, C. (2007) Intersex. New York, USA: Berg Publishers. [ Links ]

Herek, G. M. (1988) Heterosexuals' attitudes towards lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research, 25, 451-477. [ Links ]

Herek, G. M. (2000) Sexual Prejudice and Gender: Do Heterosexuals' Attitudes Towards Lesbians and Gay Men Differ? Journal of Social Issues, 56(2), 251-266. [ Links ]

Herek, G. M. (2009) Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 54-74. [ Links ]

Kilianski, S. E. (2003) Explaining heterosexual men's attitudes towards women and gay men: The theory of exclusively masculine identity. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 4, 37-56. [ Links ]

Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E., Jr. (1996) Sex differences in attitudes towards homosexual persons, behavior, and civil rights: A metaanalysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 336-353. [ Links ]

Lizasoain, L., & Joaristi, L. (2003). Gestión y análisis de datos con SPSS. Madrid: ITES-PARANINFO. [ Links ]

Lottes, I., & Grollman, E. (2010). Conceptualization and Assessment of Homonegativity. International Journal of Sexual Health, 22, 219-233. [ Links ]

Meccia, E. (2003) Derechos molestos. Análisis de tres conjeturas sociológicas relativas a la incorporación de la problemática homosexual en la agenda política Argentina. Revista Argentina de Sociología, 1(1), 59-76. [ Links ]

Moral de la Rubia, J., & Valle de la O, A. (2011) Escala de Actitudes hacia Lesbianas y Hombres Homosexuales en México 1.Estructura factorial y consistencia interna. Revista Electrónica Nova Scientia, 3(2), 139-157. [ Links ]

Moreno, A., Herazo, E., Oviedo, H., & Campo-Arias, A. (2015). Measuring homonegativity: psychometric analysis of Herek's attitudes toward lesbians and gay men scale (ATLG) in Colombia, South America. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(7), 924-35. [ Links ]

Paradiso Sottile, P. (2013) Informe Crímenes de Odio del Año 2012 (asesinatos por orientación sexual e identidad de género). Recovered on 08/11/2013 from http://www.cha.org.ar/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/06/Informe-Cr%C3%ADmenes-de-Odio-2012.pdf. [ Links ]

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994) Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741-763. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, M., Sabucedo, J. M., & Costa, M. (1993) Factores motivacionales y psicosociales asociados a distintos tipos de acción política. Psicología Política, 7(2), 19-38. [ Links ]

Satorra, A. (2002) Asymptotic robustness in multiple group linear-latent variable models. Econometric Theory, 18(2), 297-312. [ Links ]

Shields, S. A., & Harriman, R. E. (1984) Fear of male homosexuality: cardiac responses of low and high homonegative males. Journal of Homosexuality, 10(1-2), 53-67. [ Links ]

Stoever, C. J., & Morera, O. F. (2007) A confirmatory factor analysis of the Attitudes Towards Lesbians and Gay Men (ATLG) measure. Journal of Homosexuality, 52(3-4), 189-209. [ Links ]

Vega, V. (2007). Adaptación Argentina de un inventario para medir identidad de rol de género. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 39(3), 537-546. [ Links ]

Weinberg, G. (1972) Society and the Healthy Homosexual.New York: St. Martin's. [ Links ]

Whitley, B. E., & Lee, S. E. (2000) The relationship of authoritarianism and related constructs to attitudes towards homosexuality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 144-170. [ Links ]

Wu, J., & Kwok, D. K. (2012) Psychometric properties of Attitudes Towards Lesbians and Gay Men Scale with Chinese university students. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 521-526. [ Links ]