Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versión impresa ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.34 no.2 Bogotá abr./jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.391

Original articles

Comparison of two periods in liver transplantation at Colombian medical center

1Unidad de Hepatología y Trasplante Hepático, Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe, Medellín, Colombia

2Unidad de Hepatología y Trasplante Hepático, Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe. Grupo de Gastrohepatología, Universidad de Antioquia. Medellín, Colombia

Objective:

Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for acute and chronic liver failure. Liver transplantation results have improved in recent years, so the objective of our work was to compare results from two different periods of time at a center in Colombia.

Patients and Methods:

This is a retrospective descriptive study comparing first time adult liver transplant patients from 2004-2010 (Series 1: 241 patients) and from 2011-2016 (Series 2: 142 patients).

Results:

The average patient age was 54 years, 57% were men, and the average MELD score was 20. There were no significant differences between the characteristics of donors and recipients from one period to the next. The main indications for liver transplantation were alcoholic cirrhosis and cryptogenic and autoimmune hepatitis. Series 2 contained fewer hepatitis B and C cases than did Series 1. Thirty percent of the patients had hepatocellular carcinoma. The one-year survival rates were 81% in Series 1 and 91% in Series 2, whereas five-year survival rates were 71% and 80%, respectively. The main causes of death were cancer, cardiovascular disease and sepsis. From the first period to the second period, there was a significant increase in biliary complications but no differences in infectious complications, vascular complications or cellular rejection.

Conclusion:

Short and medium term liver transplantation results at this center in Colombia have been excellent, but there have been significant improvements in patient survival rates in recent years that are similar to those reported elsewhere in the world.

Keywords: Liver transplant; cirrhosis; liver graft; rejection; retransplantation

Objetivo:

el trasplante hepático es el tratamiento de elección para la falla hepática aguda y crónica. Los resultados en el trasplante hepático han mejorado en los últimos años, así que el objetivo de nuestro trabajo es comparar la experiencia de un centro en Colombia en dos períodos de tiempo diferentes.

Pacientes y métodos:

estudio descriptivo retrospectivo donde se analizaron pacientes adultos con primer trasplante hepático en dos períodos; serie 1, entre 2004-2010 (241 pacientes); y serie 2, entre 2011-2016 (142 pacientes).

Resultados:

la edad promedio fue de 54 años, el 57 % eran hombres y con un puntaje Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) promedio de 20, sin cambios significativos en las características del donante y del receptor en los dos períodos. Las principales indicaciones de trasplante hepático fueron cirrosis por alcohol, cirrosis criptogénica y cirrosis por hepatitis autoinmune, con una disminución de los casos de hepatitis B y C en la serie 2. El 30 % de los pacientes tenía hepatocarcinoma. La supervivencia de los pacientes a 1 año fue de 81 % frente a 91 % y a 5 años fue de 71 % frente a 80 %, respectivamente. Las principales causas de muerte fueron: cáncer, enfermedad cardiovascular y sepsis. Existió un incremento significativo en las complicaciones biliares, sin diferencias en las complicaciones infecciosas, vasculares y el rechazo celular entre los dos períodos.

Conclusión:

el trasplante hepático en este centro en Colombia se relaciona con excelentes resultados a corto y mediano plazo, con una mejoría significativa en la supervivencia de los pacientes en los últimos años y con resultados similares a los reportados en otros centros del mundo.

Palabras clave: Trasplante hepático; cirrosis; injerto hepático; rechazo; retrasplante

Introduction

Liver transplantation is considered to be the treatment of choice for cirrhotic patients with chronic liver failure with complications, for acute liver failure with poor prognosis, and for hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. 1 In recent years improvements in the care of patients after liver transplantation have been associated with higher survival rates for both patients and liver grafts. Some years ago we reported the experience of our center in Colombia and described survival rates and complications similar to those described in the American and European registries. 2,3,4 With increased survival of patients after liver transplantation, there is now special concern for medium and long-term survival as well as interest in strategies to reduce complications and improve patients’ quality of life. 5 The objective of this study is to evaluate liver transplantation results in recent years and compare them to results obtained in the previous study. 2

Patients and methods

Three hundred five liver transplantations were performed at the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe in Medellín Pablo Tobón Uribe Hospital from February 2004 to December 2010. Of these, 241 were first time procedures in adult patients, the results of which have already been published. 2 One hundred sixty liver transplantations were performed from January 2011 to December 2016. Of these, 142 patients were first time procedures. Patients who underwent liver retransplantation, combined liver-kidney transplantation and other combination of organ transplantation were excluded. All donors were cadavers.

This is a retrospective and descriptive study for which information was obtained through reviewing medical records and the liver transplant database. It was authorized by the hospital’s ethics committee. The severity of liver disease was staged in all patients with the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (Child) score and the Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. All patients with hepatocellular carcinoma had to meet the Milan criteria to undergo transplantation. Individuals with acute liver failure were transplanted when they met the poor prognosis criteria of King’s College hospital. Conventional immunosuppression consisted of administration of cyclosporine or tacrolimus, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil and steroids. The latter were suspended three to six months after the procedure. In our protocol the antimetabolite is not suspended in order to reduce the calcineurin inhibitor to the lowest possible dose. When the donor was positive for cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin G (IgG) and the recipient was negative, the recipient was given universal prophylaxis for CMV. In the past, individuals without a high risk profile for CMV did not undergo any intervention, but following current international protocols, we chose preventive follow-up. 6 Patients with risk factors for fungi received prophylaxis with fluconazole, and those with high risk of Aspergillus infection (retransplant or dialysis patients) received prophylaxis with echinocandin. Patients with chronic hepatitis B infections continued with Entecavir or Tenofovir. Immunoglobulin was used intramuscularly in patients at high risk of recurrence of hepatitis B, although in recent years immunoglobulin has not been used against hepatitis B in individuals with negative viral loads, negative “e” antigen and those who are receiving adequate antiviral treatment. 7

Prior to transplantation, patients with chronic hepatitis C infections with Child A liver cirrhosis were treated with antivirals available at the time (PEG interferon alpha, ribavirin, boceprevir, or telaprevir). However, most patients received treatment following transplantation as well due to the degree of liver dysfunction. In cases of moderate to severe acute rejection confirmed by biopsy, patients were given methylprednisolone boluses and baseline immunosuppression was adjusted. Patients with renal dysfunction who were not candidates for combined liver and kidney transplant as well as patients who were Child B or C with severe ascites received 20 mg of basiliximab on days 0 and 4 to allow late introduction of the calcineurin inhibitor. All patients with poor initial function or no primary function were cataloged as having primary hepatic graft dysfunction. Piggy-back vena cava surgical technique was used without need for venovenous bypass in any patient. Conventional biliary anastomosis was performed by choledochocholedochostomy without using a T-tube but with hepatic-jejunostomy depending on the criteria of the transplant surgeon. In the postoperative period, all patients were transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) with an early extubation protocol.

Statistical analysis was based on patients’ sociodemographic and clinical variables including pre-transplant conditions, liver disease etiology, severity of condition classified by Child and MELD scores, intraoperative and postoperative variables, complications, ICU days, hospital stay, graft survival and patient survival. Initially, the type of distribution of the variables was verified and a bivariate analysis was performed using Pearson’s χ² test for categorical variables and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test to compare the ranges between independent groups. A survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier curve for graft losses and patient deaths at one and five years.

Results

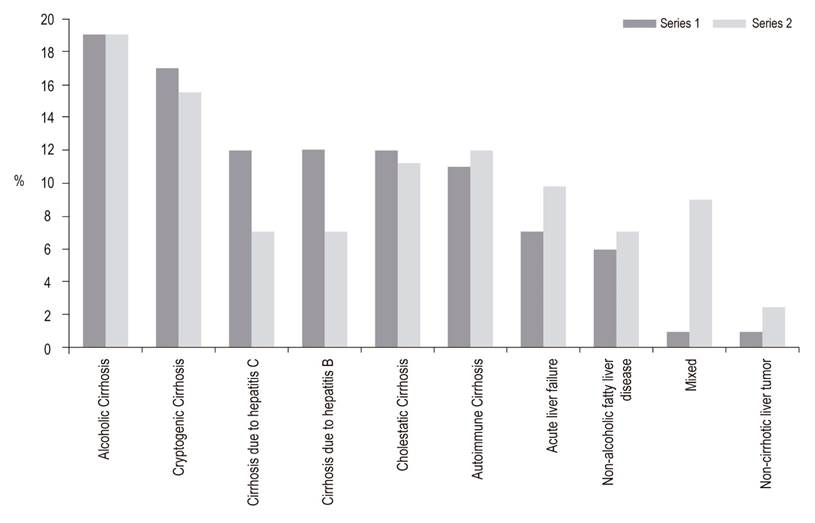

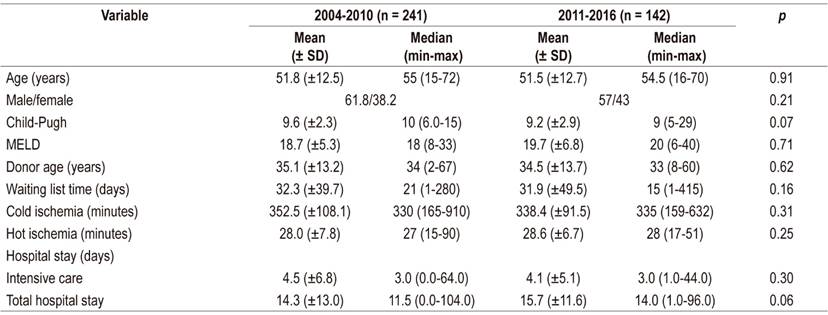

The average age of the recipients was 54 years, 57% of the recipients were male, the average MELD score was 20, and there were no differences donor and recipient characteristics between the two periods (Table 1). Liver disease etiology is described in Figure 1. The most frequent causes were alcohol cirrhosis, cryptogenic cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis cirrhosis. Comparison of the two series showed a reduction of liver transplantation for hepatitis B or C, but it was not significant. Hepatocellular carcinoma was the reason for transplantation in 25% of the cases in Series 1 (2004 -2010) compared to 30% of the patients in Series 2 (2011-2016) but the difference was not significant. Other causes include hemochromatosis, polycystic liver disease, epithelial hemangioendothelioma, Budd-Chiari syndrome, Wilson’s disease, congenital liver fibrosis and acute intermittent porphyria.

Table 1 Characteristics of liver transplant donors and recipients at Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe

SD: standard deviation; MELD: Model for End-stage Liver Disease

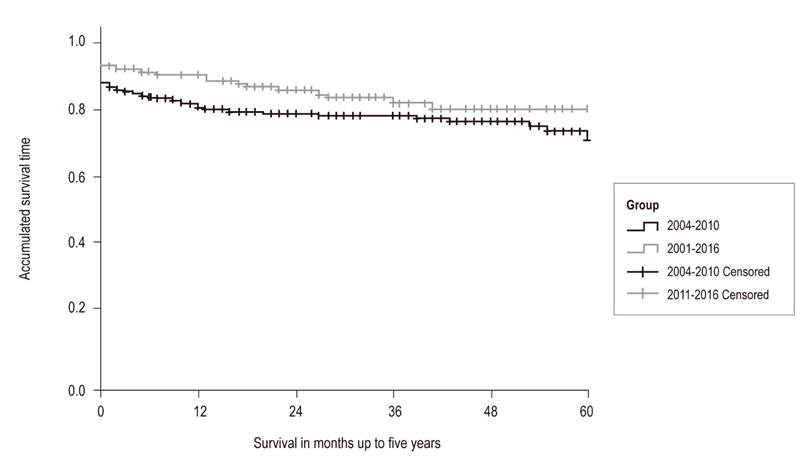

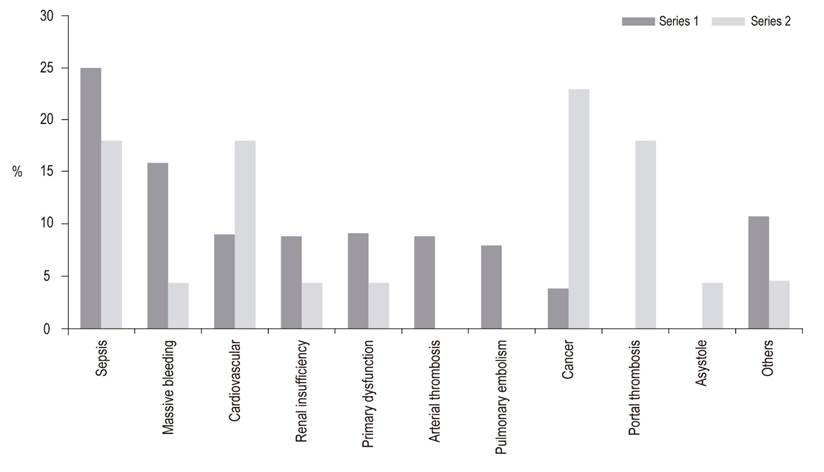

Choledochocholedochostomies were performed in 92% of patients. It was necessary to place an arterial graft for the hepatic artery in 4% of the patients. The length of ICU stay was 3 days, and the hospital stay was 14 days, without statistically significant differences. At one year, 81% of the patients in Series 1 were still alive while 91% of the patients in Series 2 survived the first year. This difference is statistically significant (p = 0.04). The five year survival rates were 71% for Series 1 and 80% for Series 2. This difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.07) (Figure 2). The 5-year liver graft survival in Series 2 was 75% without statistically significant. The main causes of death were cancer, cardiovascular disease and sepsis. Compared to Series 1, there was an increase in death due to neoplasms and cardiovascular causes in Series 2, with a decrease in deaths due to sepsis and bleeding, but there were no statistically significant differences (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Causes of death following liver transplantation in patients at the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe.

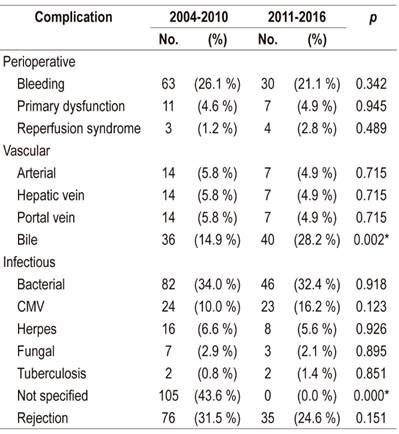

A summary of perioperative and post-transplant complications is found in Table 2. Postoperative bleeding occurred in 21% of patients, and primary hepatic graft dysfunctions were found in 4.9% without differences between the series. There were no differences in vascular complications between the series. Biliary complications occurred in 28.2% of the patients in Series 2 but in only 14.9% of the patients in Series 1. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.002). Eighty percent of these patients had anastomotic stenosis while 65% were early. Bacterial, herpes viral, fungal and mycobacterial infections did not differ significantly from what was reported in the previous series, although there was a slight increase in cases of CMV infections (16% vs. 10%). The foci of bacterial infection were abdominal in more than 50% of cases with urinary, pulmonary, soft tissue and bacteremia infections accounting for the rest. It should be noted that the only cases of disseminated toxoplasmosis and disseminated strongyloidiasis ever documented in our institution after liver transplantation appear in Series 2

Table 2 Post-transplant complications in patients at the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe

* Statistically significant difference.

CMV: cytomegalovirus.

Acute rejection was confirmed by biopsy in 24% of cases, and no cases of chronic rejection were documented. There were no differences with Series 1. Hepatic retransplantation was necessary in 4.9% of patients showing a stable rate since in Series 1 it was 6.6%.

Hepatocellular carcinoma recurred in 5% of cases as in the first series. The cause of death in all cases was recurrence that occurred in the first year with extrahepatic disease and rapid evolution. The other death-related neoplasms were post-transplant lymphoproliferative syndrome in two patients and lung cancer in one patient. The presence of skin cancer was documented in three patients but had no impact on survival.

Discussion

Liver transplantation has evolved in recent decades and is accepted as a first-line therapeutic option for patients various different liver diseases thanks to the results currently being obtained. 1,8 The most relevant result of this study is the increased 1 and 5 year survival rates. The latter is 80% higher than the rate previously reported by our center. 2 It is comparable to the rate reported in the most recent update of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) in the United States as well as those reported by referral centers in the United States and Europe. 9 This is relevant if you consider the multiple problems that exist in a country of limited resources like Colombia. We believe that the good results obtained are the product of advances in knowledge and experience of our liver transplant surgical and medical group in recent years.

This study’s short and medium term survival results are the best that have been reported in Colombia and according to our search of databases are also the best reported in Latin America. A recent study from another transplant center in Colombia has also reported good results including a 5-year survival of 79%, but patients who died during the first 30 days (15% of that cohort) were not included in that study which may bias the results. 10 Other reports from the region include those of Meirelles et al. collaborators from Brazil, who presented experience at the Albert Einstein Israelite Hospital where a 5-year survival rate of 74.3% was achieved. 11 Mattos et al. found a 5-year survival rate of 53% in southern Brazil, 12 a multicenter study in Argentina found a 1-year survival rate of 81%, 13 and a study at the Austral Hospital of Buenos Aires found a 5-year survival rate of 76. % 14.

Very recently, an international multicenter study by Muller et al. reported analysis of 7,492 liver transplant patients between 2010 and 2015 which aimed to find the best possible results in an “ideal” low risk liver transplant cohort from experienced centers in an effort to define objective references in clinically significant results after liver transplantation. 15 The low-risk cases were patients with MELD scores of less than 20, first transplantations, cadaveric donors due to brain death, and a low balance of risk (BAR) score. Based on these data, they determined that transplantation in patients with these characteristics should obtain 1-year survival rates over 90%, ICU stays of less than 4 days, hospital stays of less than 18 days, and retransplantation rates of less than 4% . These data were comparable with our results and confirm the progress of our group. It should be noted that the characteristics of most of our donors are good and the waiting times are short, both of which impact results favorably.

A very important shift in the causes of death that has occurred in recent years should be underlined: cancer and cardiovascular diseases are the most frequent causes of death in this study as well as in data reported elsewhere in the world. 16,17 Sepsis and bleeding, which were the most frequent in our first series, have both decreased. This is related to better perioperative care and greater surgical experience. Based on these results, we decided to adjust our post-transplant protocol by adding oncological screening according to the characteristics and risk factors of each patient. Series 2 reports deaths from portal thrombosis. These occurred early, so other treatment options and liver retransplantation by extension to the superior mesenteric vein were not options. Portal thrombosis had been an absolute contraindication to transplantation in our center, but in recent years, we began to perform liver transplantation in patients with this condition, and there were problems in the selection of this subgroup of patients.

Infectious complications remained stable over time, although there was a slight increase in CMV infections in Series 2. Analysis of the data shows that these infection rates were not only comparable to those reported in the literature but were actually lower. 18 Based on previous results, we decided to extend the strategy of universal prophylaxis from high-risk individuals towards preventive follow-up protocol in patients with intermediate risk of CMV infection. The rates of mycobacterial and fungal infections have remained low, and it should be noted that no invasive candida infections have been documented in recent years even though prophylaxis was directed exclusively at high-risk individuals.

The main change with respect to post-transplant complications was the significant increase in biliary complications, specifically anastomotic stenosis. An analysis of this situation made with the medical and surgical group found no objective explanation for this increase. To reduce biliary complications, we have since adopted the strategy of temporarily leaving a Nélaton probe in the bile duct for the first weeks after transplantation whenever there is a doubt about anastomosis. This has been related to a decrease in the rate of biliary stenosis (unpublished data).

The survival rate of transplant patients with hepatocellular carcinoma was similar to that of other patients. Recurrence rates were below 10% and in accord with what has been reported in the world literature when the Milan criteria are met. 19

As in other Latin American countries, alcoholic liver disease was the main indication for liver transplantation in our series. This has remained stable over time. Of liver disease etiologies, we should highlight autoimmune hepatitis which we know occurs frequently in our environment even though we do not have incidence and prevalence studies for Colombia. Recently, Díaz Ramírez et al. described the characteristics of 278 patients of which 10% required liver transplantation. 20 In this study, we document a reduction in the indication of liver transplantation for hepatitis B and hepatitis C which we associate with better available treatment options. This is something that we hope to improve in the next years. These findings coincide with current reports from elsewhere in the world.

Limitations of this study include its single-center design and exclusion of retransplant patients, combined liver-kidney transplant patients, and other multiple organ transplant patients due to the difficulties of comparing characteristics of these patient groups.

In conclusion, liver transplantation is an effective first-line therapy for various acute and chronic liver diseases in selected patients. Short and medium term results at the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe in Medellín are comparable to those obtained in the United States and Europe.

REFERENCES

1. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2016 Feb;64(2):433-485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.006 [ Links ]

2. Santos O, Londoño M, Marín J, Muñoz O, Mena Á, Guzmán C, et al. An experience of liver transplantation in Latin America: a medical center in Colombia. Colomb Med (Cali). 2015 Mar 30;46(1):8-13. https://doi.org/10.25100/cm.v46i1.1400 [ Links ]

3. Thuluvath PJ, Guidinger MK, Fung JJ, Johnson LB, Rayhill SC, Pelletier SJ. Liver transplantation in the United States, 1999-2008. Am J Transplant. 2010 Apr;10(4 Pt 2):1003-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03037.x [ Links ]

4. Adam R, Karam V, Delvart V, O’Grady J, Mirza D, Klempnauer J, et al. Evolution of indications and results of liver transplantation in Europe. A report from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR). J Hepatol . 2012 Sep;57(3):675-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.015 [ Links ]

5. De Bona M, Ponton P, Ermani M, Iemmolo RM, Feltrin A, Boccagni P, et al. The impact of liver disease and medical complications on quality of life and psychological distress before and after liver transplantation. J Hepatol . 2000 Oct;33(4):609-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80012-4 [ Links ]

6. Kotton CN, Kumar D, Caliendo AM, Asberg A, Chou S, Danziger-Isakov L, et al. Updated international consensus guidelines on the management of cytomegalovirus in solid-organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2013 Aug 27;96(4):333-60. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e31829df29d [ Links ]

7. Fung J, Wong T, Chok K, Chan A, Cheung TT, Dai JW, et al. Long-term outcomes of entecavir monotherapy for chronic hepatitis B after liver transplantation: Results up to 8 years. Hepatology. 2017 Oct;66(4):1036-1044. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29191 [ Links ]

8. Lucey MR, Terrault N, Ojo L, Hay JE, Neuberger J, Blumberg E, et al. Long-term management of the successful adult liver transplant: 2012 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013 Jan;19(1):3-26. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.23566 [ Links ]

9. Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, Schladt DP, Skeans MA, Harper AM, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report: Liver. Am J Transplant . 2018 Jan;18 Suppl 1:172-253. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.14559. [ Links ]

10. Londoño JF, Agudelo Y, Guevara G, Cardona D. Factores clínicos y demográficos asociados con la supervivencia de los pacientes mayores de 14 años con trasplante hepático, en el hospital universitario de San Vicente Fundación, 2002 a 2013. Rev Col Gastroenterol. 2016 Sep;31(3): 208-215. https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.92 [ Links ]

11. Meirelles Júnior RF, Salvalaggio P, Rezende MB, Evangelista AS, Guardia BD, Matielo CE, et al. Liver transplantation: history, outcomes and perspectives. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2015 Jan-Mar;13(1):149-52. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-45082015RW3164 [ Links ]

12. Mattos ÂZ, Mattos AA, Sacco FK, Hoppe L, Oliveira DM. Analysis of the survival of cirrhotic patients enlisted for liver transplantation in the pre- and post-MELD era in southern Brazil. Arq Gastroenterol. 2014 Jan-Mar;51(1):46-52. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-28032014000100010 [ Links ]

13. Cejas NG, Villamil FG, Lendoire JC, Tagliafichi V, Lopez A, Krogh DH, et al. Improved waiting-list outcomes in Argentina after the adoption of a model for end-stage liver disease-based liver allocation policy. Liver Transpl . 2013 Jul;19(7):711-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.23665 [ Links ]

14. Piñero F, Cheang Y, Mendizabal M, Cagliani J, Gonzalez Campaña A, Pages J, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes related with neurological events after liver transplantation in adult and pediatric recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2018 May;22(3):e13159. https://doi.org/10.1111/petr.13159 [ Links ]

15. Muller X, Marcon F, Sapisochin G, Marquez M, Dondero F, Rayar M, et al. Defining Benchmarks in LiverTransplantation : A Multicenter Outcome Analysis Determining Best Achievable Results. Ann Surg. 2018 Mar;267(3):419-425. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002477 [ Links ]

16. VanWagner LB, Lapin B, Levitsky J, Wilkins JT, Abecassis MM, Skaro AI, et al. High early cardiovascular mortality after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl . 2014 Nov;20(11):1306-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.23950 [ Links ]

17. Watt KD, Pedersen RA, Kremers WK, Heimbach JK, Sanchez W, Gores GJ. Long-term probability of and mortality from de novo malignancy after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2009 Dec;137(6):2010-7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.070 [ Links ]

18. Kotton CN, Kumar D, Caliendo AM, Huprikar S, Chou S, Danziger-Isakov L, et al. The Third International Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Cytomegalovirus in Solid-organ Transplantation . Transplantation. 2018 Jun;102(6):900-931. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000002191 [ Links ]

19. Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996 Mar 14;334(11):693-9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199603143341104 [ Links ]

20. Díaz-Ramírez GS, Marín-Zuluaga JI, Donado-Gómez JH, Muñoz-Maya O, Santos-Sánchez Ó, Restrepo-Gutiérrez JC. Characterization of patients with autoimmune hepatitis at an university hospital in Medellín-Colombia: cohort study. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;41(2):87-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2017.09.003 [ Links ]

Received: July 24, 2018; Accepted: October 09, 2018

texto en

texto en