Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

versión impresa ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.26 no.1 Medellín jul./dic. 2014

LITERATURE REVIEW

PREDISPOSING FACTORS FOR GINGIVAL INFLAMMATION ASSOCIATED WITH STEEL CROWNS ON TEMPORARY TEETH IN THE PEDIATRIC POPULATION. A SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW

Daniela Madrigal López1; Esther María Viteri Buendía2; Mario Rafael Romero Sánchez3; María Marcela Colmenares Millán4; Ángela Suárez5

1 Dentist, Universidad Latina de Costa Rica. Pediatric Dentistry Specia-

list, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá D. C., Colombia

2 Dentist, Universidad de Guayaquil, Ecuador. Pediatric Dentistry

Specialist, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá D. C., Colombia

3 Dentist, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia.

Pediatric Dentistry Specialist, Universidad de Costa Rica. Head of the

Depar tament of Craneofacial System, professor, Pontificia Universidad

Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia

4 Dentist, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia.

Periodontics Specialist, professor, Facultad de Odontología, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá.

E-mail: romero.mario@javeriana.edu.co

5 Dentist, Universidad El Bosque. Epidemiology Specialist, Universidad

El Bosque, professor, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Institución

Universitaria Colegios de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia

SUBMITTED: MAY 14/2013-ACCEPTED: OCTOBER 8/2014

Madrigal D, Viteri EM, Romero MR, Colmenares MM, Suárez Á. . Predisposing factors for gingival inflammation associated with steel crowns on temporary teeth in the pediatric population. A systematic literature review. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2014; 26(1): 152-163.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: the objective of this systematic review was to determine the predisposing factors for gingival inflammation produced by

steel crowns, compared to unrestored temporary teeth in the pediatric population.

METHODS: a systematic literature review by searching scientific

articles in these databases: Pubmed, Elsevier, Embase, Cochrane, and Lilacs using the following terms: stainless steel crowns, pediatric crowns,

gingivitis, pediatric dentistry, clinical parameters, and child, and reducing the search with eligibility criteria with no language distinction. This

search included analytic observational studies, clinical trials, and systematic reviews. The studies' quality and validity after final filtration were

evaluated with two checklists: CONSORT (clinical trials) and STROBE (cross-sectional analytical observational studies). They were later classified

according to levels of evidence and degrees of recommendation, according to the parameters of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network.

RESULTS: once the process of reading and information analysis was completed, 1450 articles were identified in the period of study (1970-2012)

and 10 were selected as they met the inclusion criteria. Duplicates were discarded as well as those that did not meet the specifications required to

answer the research question. Finally, 2 articles were chosen as they met the previously set requirements.

CONCLUSIONS: : the scientific evidence was

not enough to support the fact of steel crowns adaptation being one of the predisposing factors for gingival disease in the pediatric patients, nor

does it prove the alteration of periodontal tissue by invading biological thickness due to the over-extension of steel crowns. The variable related

to excessive cement material has not been widely documented. While a clinical study showed that gingival health is affected by steel crowns in the

presence of dental biofilm, the literature is not conclusive regarding the behavior of gingival tissue in the pediatric population.

Key words: crowns, stainless steel, gingivitis, pediatric dentistry, child.

INTRODUCTION

Steel crowns were first introduced to pediatric dentistry by W. P. Humphrey in 1950. These types of restorations have not been replaced to a different material since then. They are preformed semipermanent restorations on the occlusal anatomy, cemented with a biocompatible agent, and used to preserve teeth that have lost their integrity for various reasons. Crown sealing must be accurately performed between the crown's border and the preparation line.1-4

The suggested technique to adapt steel crowns consists on locally anesthetize the area to treat, check occlusion, isolate with rubber dam, and prepare the tooth (reduce proximal surfaces with a slight convergence towards occlusal —engaging the sub-gingival area and eliminating interproximal contacts—, perform occlusal reduction rounding sharp angles and, if necessary, reduce both buccal and lingual surfaces). The adequate crown is then selected. It is marked, cut, fit, outlined, and completed (polishing gingival margin). Occlusion is checked and adjusted and the crown is finally cemented (removing excess of cementing material).5-7

Various authors suggest that in order to get favorable results in treatments performed on with steel crowns there must be adequate marginal adaptation to allow good periodontal health, as well as functional occlusion and an optimal cementation procedure.1, 8-10

Regarding the parameters of apparent periodontal normality in the pediatric population, the most important features are: color, which depends on the relationship among vascular availability, thickness, and epithelium keratinization, as well as the amount of connective tissue. Color is more intense in kids (reddish) but it declines with age, when the amount of blood vessels decreases. In terms of appearance, it is smooth and shiny due to the reduction or absence of gingival pitting and the presence of less fibrous connective tissue; consistency of the latter can be softer than in the adult population due to weaker connective tissue. The gingival tissue inflammatory response to biofilm accumulation depends on the kid`s microbiological, histological, and immunological characteristics.1, 2

Periodontal disease is the expression of the tissues' inflammatory response to bacterial plaque products, and its manifestation depends on the characteristics of various local and systemic factors and on the duration of plaque presence. Gingivitis is the predominant form of periodontal disease in children and adolescents, and it consists of a non- specific inflammation of the marginal gingiva.1, 11-13

Controversy exists in the literature with regard to the state of the gingival tissue of teeth treated with a steel crown. Similarly, the literature has reported greater gingival inflammation in temporal dentition in these cases.14-19

Steel crowns are indicated in pediatric dentistry to cover teeth surfaces when they have been severely affected by dental caries, in the presence tooth development defects and traumatic dental fractures, and after pulpotomy and pulpectomy. The literature reports little evidence on the possible effects of steel crowns on gingival tissue; it is therefore suggested to update research on this subject in order to answer the research question through a systematic literature review, since the pediatric population's gingival health has been studied for years.1-4

It has been reported that gingivitis often occurs around primary teeth restored with steel crowns due to diverse factors, mainly to improper techniques during all the aforementioned therapeutic process. Studies performed on animals (dogs) with steel crowns have shown that overcountoured crowns subgingivally located seem to slightly affect periodontal tissues after being used for three months with a strict regimen of oral hygiene.13, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21

The objective of this review was to identify the predisposing factors for gingival inflammation associated with steel crowns in deciduous teeth in the pediatric population, through a systematic literature review.

METHODS

This was a systematic literature review on the scientific evidence published between 1970 and 2012 about predisposing factors for gingival inflammation associated with steel crowns in the pediatric population. Information was obtained from electronic databases such as Pubmed, Elseiver, Embase, Lilacs, and Cochrane, with terms commonly used for bibliographic search: stainless steel crowns, pediatric crowns, gingivitis, pediatric dentistry, clinical parameters, and child.

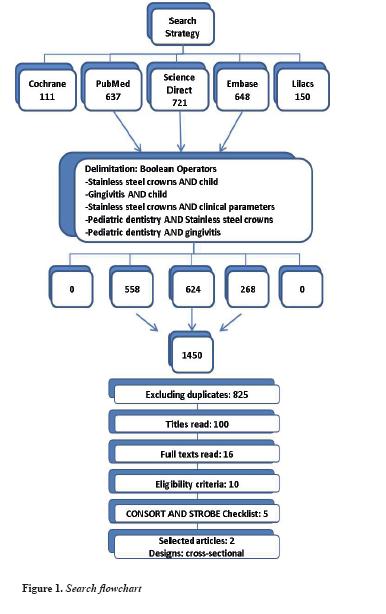

Articles were selected by the leading researchers, who initially reviewed the titles of scientific papers, then the abstracts of selected studies, and finally they read the full texts of articles that met the eligibility criteria for the present study (table 1). The selected articles were analyzed according to the levels of evidence and degrees of recommendation, following the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). The articles that met the eligibility criteria were later reviewed and evaluated through two checklists (CONSORT and STROBE) suggested for the clinical studies connected with the proposed clinical question (figure 1).

RESULTS

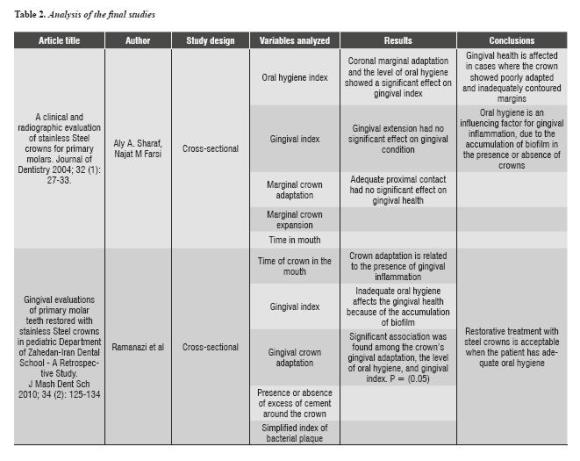

A total of 1450 articles were identified in the period of study (1970-2012), and 10 were selected as they met the inclusion criteria. Duplicates were discarded as well as those that did not meet the specificity required to answer the research question. Finally, 2 articles were selected as they met the requirements previously set. With 2 final articles, we sought to answer the research question, intended to determine the predisposing factors for gingival inflammation associated with steel crowns in deciduous teeth in the pediatric population (table 2).

According to steel crowns adaptation and its impact on gingival tissue, Sharaf et al demonstrated significant differences in relation to gingival adaptation and periodontal status, with P values of 0.02. Ramazani et al show significant differences in relation to gingival adaptation and periodontal status (P value 0.001).22, 23

Concerning the extension of steel crowns and its impact on gingival tissue, Sharaf et al showed no effect on gingival tissue arising from this condition (P value 0.056). Ramazani et al did not include this variable in their study.22, 23

Crown polishing was not described in any of the two final articles, since this variable was not included in the studies.22, 23

Excesses of cementing material were not described in the scientific article by Sharaf et al. According to Ramazani et al, there is no relationship between excesses of cementing material on the crowns and their impact on gingival tissue (P value 0.27).22, 23

Regarding biofilm accumulation and its impact on gingival tissue, Sharaf et al did not include this variable in their study, while Ramazani et al demonstrated a significant difference between gingival health and steel crowns (P value 0.0001).22, 23

DISCUSSION

The association of steel crowns and gingival inflammation has not been fully explained in the literature. It has been suggested that gingival inflammation may be associated with predisposing factors.

Concerning crown adaptation, the studies by Sharaf and Farsi (2004) and Ramazani et al (2010) showed that crown marginal adaptation and the level of oral hygiene have an effect on gingival index. This is supported by various studies carried out by Durr (1982), Henderson (1973), and Myers (1975), who reported a high incidence of gingivitis around incorrectly contoured crowns. These results disagree with those of Checchio's study (1983), in which bad adaptation showed no relationship with periodontal problems. However, the current literature is not conclusive in terms of the relationship between crown marginal adaptation and the presence of gingival disease in the pediatric population.17, 20, 22-25

The study by Sharaf and Farsi (2004) showed that marginal coronal extension had no effect on gingival conditions. However, Myers (1975) showed a significant association between crown defects and clinical evidence of gingivitis (P < 0.001), extension being the most common error, with 34%. Clinical evidence shows, however, that invasion of biological thickness leads to the development of inflammatory entities in the periodontium in the adult population.22-26

Analysis of the two selected articles yielded no evidence regarding the impact of steel crowns polishing on the health of gingival tissue. Myers (1980) reported that plaque accumulation occurs regardless of polishing type. However, studies in adults show differences in surface energy between restored and unrestored teeth, influencing adhesion of dental biofilm, which is reflected in the degree of gingival inflammation that may exist around teeth with some type of restoration.22, 23, 27, 28

Similarly, analysis of the final articles showed no evidence on the excesses of cementing material of steel crowns and their impact on gingival tissue. The variable related to excesses of cementing material has not been widely documented by the current scientific literature.22, 23

Concerning accumulation of dental biofilm, Sharaf and Farsi (2004) showed that oral hygiene does affect gingival health. Children with inadequate oral hygiene showed higher frequency of gingivitis, while children with proper oral hygiene showed a healthy gingiva around steel crowns. Checchio (1983) claims that gingival inflammation is two times more frequent in patients with poor oral hygiene and in the presence of steel crowns. The study by Ramazani et al (2010) showed that gingival health is affected by steel crowns in the presence of biofilm. This is supported by Durr et al (1982), who stated that there is a correlation between accumulation of dental biofilm and gingivitis in teeth restored with steel crowns. The literature was not conclusive in relation to the behavior of gingival tissue in the presence of biofilm in unrestored or somehow restored teeth.17, 22, 23, 25

The analysis of the different studies included in this systematic review show a great heterogeneity in terms of epidemiological indices to measure gingival status and dental biofilm; there are no standardized indices for temporary dentition, which impedes protocol standardization and evidence- based clinical practice guidelines.

CONCLUSIONS

- There is no sufficient scientific evidence to support that adaptation of steel crowns is one of the predisposing factors for gingival disease in pediatric patients.

- There is no sufficient scientific evidence to demonstrate periodontal tissue alteration by the invasion of biological thickness due to over- extension of steel crowns.

- The variable related to excesses of cementing material has not been widely documented as a predisposing factor for developing gingival disease in temporary dentition.

- Although one clinical study showed that gingival health is affected by steel crowns in the presence of dental biofilm, the literature is not conclusive in terms of the behavior of the pediatric population's gingival tissue.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The primary caregiver and the pediatric patient should understand the importance of maintaining good oral hygiene and regular professional supervision. We suggest carrying out analytical, descriptive, observational studies and clinical trials in order to determine the effects of steel crowns, biofilm accumulation, and gingival conditions.

It is also suggested to carry out studies to determine the relationship between the crowns' material and dental biofilm adhesion.

Taking into account the heterogeneity of the indices used in the articles included in this study, it is suggested to standardize the epidemiological indices in order to obtain more reliable measurements.

REFERENCES

1. Carrillo A, Méndez P. Fundamentos de la Odontología Odontopediatría. Bogotá: Javegraf; 2009. [ Links ]

2. Cárdenas D. Odontología Pediátrica. 4.a ed. Medellín: Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas; 2009. [ Links ]

3. Bellet L, Sanclemente C, Casanova M. Coronas en odontopediatría: revisión bibliográfica. Dentum 2006; 6(3): 111-117. [ Links ]

4. Pinkham JR. Odontología pediátrica. 3.a ed. México D. F.: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [ Links ]

5. Kindelan SA, Day P, Nichol R, Willmott N, Fayle SA. UK National clinical guidelines in paediatric dentistry: stainless steel preformed crowns for primary molars. Int J Paediatr Dent 1997; 7: 267-268. [ Links ]

6. American Association of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Pediatric Restorative Dentistry. Pediatr Dent 2008; 30 (7 Supl): 163-169. [ Links ]

7. Guelmann M, Matsson L, Bimstein E. Periodontal health at first permanent molars adjacent to primary molar stainless steel crowns. J Clin Periodontol 1988; 15(9): 531-533. [ Links ]

8. Croll TP, Epstein DW, Castaldi CR. Marginal Adaptation of stainless steel crowns. Pediatr Dent 2003; 25(3): 249- 252. [ Links ]

9. Salama FS, Myers DR. Stainless Steel Crown in clinical pedodontics: a review. Saudi Dent J 1992; 4 (2): 70-74. [ Links ]

10. Sorensen JA. A rationale for comparison of plaqueretaining properties of crown systems. J Prosthet Dent 1989; 62(3): 264-269. [ Links ]

11. Bimstein E, Ebersole JL. The age-dependent reaction of the periodontal tissues to dental plaque. ASDC J Dent Child 1989; 56(5): 358-362. [ Links ]

12. Mattson L. Factors influencing the susceptibility to gingivitis during childhood. A review. Int J Paediatric Dent 1993; 3(3): 119-127. [ Links ]

13. Bimstein, E, Lustmann J, Soskolne WA. A clinical and histometric study of gingivitis associated with the human deciduous dentition. J Periodontol 1985; 56(5): 293-296. [ Links ]

14. Zyskind K. Periodontal health as related to preformed crowns: report of a case. ASDC J Dent Child 1989; 56(5): 385-387. [ Links ]

15. Einwag J. Effect of entirely preformed stainless steel crowns on periodontal health in primary, mixed dentitions. ASDC J Dent Child 1984; 51(5): 356-359. [ Links ]

16. Reitemeier B, Hänsel K, Walter MH, Kastner C, Toutenburg H. Effect of posterior crown margin placement on gingival health. J Prosthet Dent 2002; 87(2):167-172. [ Links ]

17. Durr DP, Ashrafi MH, Duncan WK. A study of plaque accumulation and gingival health surrounding stainless steel crowns. ASDC J Dent Child 1982; 49(5): 343-346. [ Links ]

18. Bimstein E, Delaney JE, Sweeney EA. Radiographic assessment of the alveolar bone in children and adolescents. Pediatr Dent 1988; 10(3): 199-204. [ Links ]

19. Kohal RJ, Gerds T, Strub JR. Effect of different crown contours on periodontal health in dogs. Clinical results. J Dent 2003; 31(6): 407-413. [ Links ]

20. Henderson HZ. Evaluation of the preformed stainless steel crown. ASDC J Dent Child 1973; 40(5): 353-358. [ Links ]

21. Fuks AB, Zadok S, Chosack A. Gingival health of premolar successors to crowned primary molar successors to crowned primary molars. Pediatr Dent 1963: 5(1): 51-52. [ Links ]

22. Sharaf AA, Farsi NM. A clinical and radiographic evaluation of stainless steel crowns for primary molars. J Dent 2004; 32(1): 27-33. [ Links ]

23. Ramazani M, Ramazani N, Honarmand M, Ahmadi R, Daryaeean M, Hoseini MA. Gingival evaluation of primary molar teeth restored with stainless steel crowns in pediatric department of Zahedan-Iran dental school. A retrospective study. J Mash Dent Sch 2010; 34(2): 125-134. [ Links ]

24. Myers, DR. A clinical study of the response of the gingival tissue surrounding stainless steel crowns. J Dent Child 1975; 42(4): 281-284. [ Links ]

25. Checchio LM, Gaskill WF, Carrel R. The relationship between periodontal disease and stainless steel crowns. J Dent Child 1983; 50(3): 205-209. [ Links ]

26. Kina JR, Dos Santos PH, Kina E, Suzuki T, Dos Santos PL. Periodontal and prosthetic biologic considerations to restore biological width in posterior teeth. J Craniofac Surg 2011; 22(5): 1913-1916. [ Links ]

27. Myers DR, Schuster GS, Bell RA, Barenie JT, Mitchell R. The effect of polishing technics on surface smoothness and plaque accumulation on stainless steel crowns. Pediatr Dent 1980; 2(4): 275-278. [ Links ]

28. Ababneh KT, Al-Omari M, Alawneh TN. The effect of dental restoration type and material on periodontal health. Oral Health Prev Dent 2011; 9(4): 395-403. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en