Introduction: Truth Commissions as Processes

One of the recent critiques of transitional justice and research on the impact of transitional justice mechanisms is their focus on preconceived outcomes rather than on the process and how this process links to an outcome. Gready and Robins join others in advocating for a change from transitional to transformative justice. Transformative justice would propose, among other measures, “a focus on civil society participation in the design and implementation of transitional justice mechanisms” (Lambourne 2009, 28). For Gready and Robins,

Transformative justice and transformative participation require more focus on process, on the interface between process and outcomes and on mobilization, and less focus on preconceived outcomes. Such mobilization can take place around court proceedings, truth commissions or reparations advocacy, or simply around the needs of victims and citizens. It can seek to support, shape or contest such mechanisms. (Gready and Robins 2014, 358)

Among these transitional justice mechanisms, Truth Commissions (TCs) are expected to help post-conflict societies establish the facts about past human rights violations, foster accountability, preserve evidence, identify perpetrators and recommend reparations and institutional reforms (Secretary-General 2004, para.50). If we consider TCs as processes, public engagement with them could be sustained over time.

In this document, I argue that TCs are processes that allow for mobilization and participation from victims and civil society on a broader level. If we examine TCs as processes, we can clearly distinguish three different chronological stages with different degrees of public engagement. The first stage would comprise the time leading to the establishment of a TC and it encompasses a period that could be characterized by social mobilization and participation through discussions, negotiations or consultations with victims and civil society. The second stage would comprise the time since the commission starts its work and up to the submission of its final report, when it ceases to exist. The third stage comprises the period after the submission of the commission’s final report, which can easily last a number of years.

In this article, I examine the relationship between victims and civil society with pro-democracy political parties in the lead up to the establishment of a TC (first stage) and after the commission’s recommendations in its final report (third stage). What the Nepal and Sri Lanka cases suggest is that a close relation between civil society and pro-democracy political parties leading to the establishment of a TC can limit the pressure civil society exerts on the implementation of recommendations, once those pro-democracy political parties are in the new government.

There are few studies that analyze the implications of civil society and victims’ mobilizations prior to the establishment of TCs and in the post-commission stage. One of them examines participatory commissions as those in which civil society, politicians and commissioners and staff are able to “exercise agency with respect to the commission’s goals, procedures, and methodology” (Bakiner 2016, 116). According to this scholar, participatory commissions are more likely to produce indirect political impact as civil society actors who participated in the process will mobilize around their recommendations (Bakiner 2016, 116). However, in the cases I present, it is precisely the close relationship between civil society and victims with political party leaders that deters mobilization once those leaders are part of the new government.

This article attempts to contribute to the understanding of the effects of TCs by examining two early commissions: the Mallik Commission established in Nepal in 1990 and the Zonal Commissions of Inquiry into disappearances established in Sri Lanka in 1994. In the first section, I explain that civil society and victims’ active mobilization around a TC can be analyzed as a relation of vertical accountability, where victims and civil society press the governing regime to establish a TC. Sections 2 and 3 apply the accountability framework to the commission established in Nepal and Sri Lanka. What the Nepal and Sri Lanka cases show is the existence of a continuum during the pre and post-commission stages. A continuum that might explain TCs’ frequent lack of implementation of recommendations, at least in post-authoritarian settings.

1. Truth Commissions and Accountability Relationships

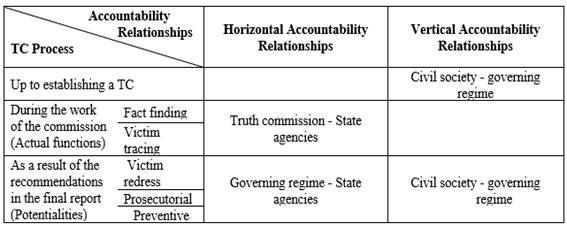

I have examined the relationship between TCs and accountability (Fernandez-Torne 2015). Specifically, TCs can generate vertical and horizontal accountability relationships. First, the establishment of a TC can be the result of a relationship of vertical accountability between civil society and the governing regime. Second, during the period between the establishment and the submission of the report, TCs hold state agencies horizontally accountable by carrying out fact-finding and victim tracing functions. As a result of the recommendations in the final report, TCs generate, first, a relationship of horizontal accountability between the governing regime and the state agencies towards which the recommendations are directed. Second, TCs’ recommendations can also generate a vertical accountability relationship between civil society and the governing regime. This vertical accountability relationship takes place when the governing regime implements the recommendations as a result of civil society pressure. In other words, when the recommendations in a TCs’ final report are used as a checklist to hold governments accountable for their implementation (see table 1).

a. Vertical Accountability Relationships

In this article, I focus on vertical accountability relationships. Vertical accountability refers to the state being held accountable by non-state agents, mainly by citizens and their associations (Goetz and Jenkins 2002, 7). Elections would be the example of citizens holding accountable those in office. For some, electoral accountability would be the only instance of vertical accountability. The reason being that it is the only relationship that gives citizens formal authority of oversight and/or sanction over public officials. However, this narrow definition excludes many of the processes that are not based on formal authority, but still generate political accountability in practice (Fox 2007a, 32). Thus vertical accountability would also include “processes through which citizens organize themselves into associations capable of lobbying governments, demanding explanations and threatening less formal sanctions like negative publicity” (Goetz and Jenkins 2002, 7). These processes can take place against those who occupy positions in state institutions, regardless of whether or not they have been elected. O’Donnell includes social demands to denounce wrongful acts of public authorities, helped by a reasonably free media, as dimensions of vertical accountability (O'Donnell 1999, 29-30).

Other authors refer to these processes as societal accountability, a third way of holding governments accountable (Ackerman 2003, 449). In processes of societal accountability, civil society controls the government, by exposing and denouncing wrongdoing, for example, through social mobilization; and by activating the operation of horizontal mechanisms (Smulovitz and Peruzzotti 2000, 152). What differentiates these demands in a relationship of vertical or societal accountability is that the state is compelled to respond. If there is no state answerability, the actions of citizens’ associations, movements and media are voice understood to describe “how citizens express their interests, react to governmental decision-making or the positions staked out by parties and civil society actors, and respond to problems in the provision of public goods” (Goetz and Jenkins 2002, 9).

b. Vertical Accountability and Truth Commissions

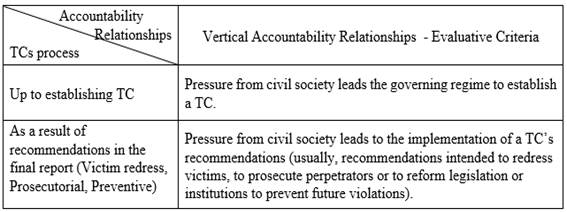

Truth Commissions can generate vertical accountability relationships at two different stages: first, during the period leading to the establishment of a commission and, second, as a result of the commission’s recommendations in the final report. In the first stage, the establishment of a TC can be the result of a relationship of vertical accountability between civil society and the governing regime. In analyzing what has to happen to conclude that the establishment of a TC is the result of vertical accountability, I propose that we should evaluate whether civil society pressure leads the governing regime to establish a TC. The establishment of a TC entails an activation of a horizontal mechanism to look into the wrongdoings at the base of social mobilization.

Vertical accountability relationships also occur because of the recommendations in a TC’s final report. The recommendations of a TC are not only intended for the governing regime, but also directed at the victims and broader civil society. As a matter of fact, agencies of horizontal accountability, such as TCs, “rarely have sufficient institutional clout to be able to act on their findings, whether by proposing mandatory sanctions, policy changes, protection from violations, or compensation for past abuses” (Fox 2007b, 666). For Fox, to address these issues of hard accountability, it is necessary to “deal with both the nature of the governing regime and civil society’s capacity to encourage the institutions of public accountability to do their job” (Fox 2007b, 669). If the governing regime remains inactive and does not implement those recommendations, civil society can intercede and push the governing regime to do so.

It is through civil society advocacy, leadership, and persistence that the commission’s recommendations could eventually be implemented even when the governing regime lacks the will or the political clout to do so. As the special rapporteur has pointed out, “[i]n the end, the fate of recommendations depends to a large extent on the leadership, advocacy and persistence of civil society organizations” (Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth 2013, para.73). Here, I propose an evaluation of whether the pressure from civil society leads to the implementation of a TC’s recommendations. Evaluative criteria are compiled in the table below.

Table 2 includes the evaluative criteria showing when a governing regime is held accountable by civil society. In the next section, I apply the previous framework to the commissions established in Nepal (1990) and in Sri Lanka (1994). To this end, I assess whether or not the evidence collected through documentary sources and semi-structured interviews fulfill the evaluative criteria.

2. Case Study: The 1990 Mallik Commission in Nepal

In this section, I first present an overview of the 1990 transition from Panchayat regime to multiparty democracy and the role of civil society to understand the context in which the Mallik commission was established. Next I assess whether or not pressure from civil society led the governing regime to establish the Mallik commission; and whether or not pressure from civil society led to the implementation of the Mallik commission’s recommendations. Finally, I explain the reasons behind the lack of implementation.

a. The 1990 Transition and the Role of Political Parties and Civil Society

On February 18, 1990, the Nepali Congress (NC) and seven communist parties that had joined to form the United Left Front (ULF) launched the jana andolan (people’s movement), a peaceful and non-violent mass movement for the restoration of democracy against the autocratic Panchayat regime.1 Regarding the factors that encouraged the People’s Movement, some argue that the increase of international attention on human rights empowered those who were already advocating for political and social change (Adams 1998, 84). Human rights organizations, in particular, had become important in Nepal as they were allowed to exist at a time when political parties were banned. Since their emergence in the mid 1980s, they were closely linked to political parties.

Two organizations, the Human Rights Organization Nepal (HURON) and the Forum for Protection of Human Rights (FOPHUR), would play a central role during the People’s Movement. While FOPHUR was closer to the leftist parties, HURON was supported by the NC and others. Most of the human rights activists in these organizations had also been active party members. As a human rights activist with HURON, put it, “we used to have dual identity; we could neither give up our political identity, nor could we give up our new found identity as human rights activists” (interview Kapil Shrestha, 2014). As a result of this close relationship between human rights organizations and political parties, the latter also incorporated the human rights discourse in their strategy against Panchayat. In short, it was a time “of close relationship and partnership between democratic parties and human rights defenders” (Pyakurel 2013, 1).

Dr. Mathura Prasadh Shrestha (FOPHUR) and Devendra Raj Panday (HURON) emerged as key civil society leaders during the people’s movement. They both coordinated the Professional Solidarity Groups, groups of citizens organized according to their profession that engaged in activism in their professional environment. Medical professionals played a key role in determining that the police were using a type of dum-dum bullet that had been altered so that they would explode inside the victim’s body (Adams 1998, 90). As a result, on February 23, 1990 doctors organized a silent strike of two hours that was felt as legitimizing the protest for the public at large (Adams 1998, 93). Medical professionals also protected political leaders from arrest by placing them under hospital bed rest. Lawyers boycotted legal proceedings at various courts to protest the police violence against pro-democracy supporters (Parajulee 2000, 83).

Increased demands to respect human rights as a response to the atrocities committed by security forces redefined the movement (Adams 1998, 104). As a result, the struggle was not about allowing political parties in the system anymore, but about prevailing injustice committed by a repressive regime. On April 6, 1990, amid mounting protests, the King dissolved the government and appointed Lokendra Bahadur (L.B.) Chand, a moderate member of the Panchayat regime, as the Prime Minister (PM) to form a new council of ministers. On April 8, 1990, when the King agreed to end the ban on political parties and introduce a multiparty system, political party leaders declared the end of the people’s movement. However, the agreement did not mention the abolishment of the Panchayat institutions or the formation of a new government.

On April 11, 1990, the Professional Solidarity Group issued a statement signed by the two civil society leaders, Mathura Prasadh Shrestha and Devendra Raj Pandey, appealing to the representatives of the NC and ULF to take a firm stand in their talks with the Monarch with respect to 1) the immediate formation of an interim government with representatives of various political parties; 2) the dissolution of all units of the Panchayat system and drafting of a new constitution; 3) honoring of and compensation to the families of those killed and provision of full and free medical attention to those injured; 4) investigation into the killings and repression perpetrated during the movement and punishment of those guilty (Adams 1998, 134-135).

On April 15, 1990, a week after political party leaders had declared the end of the people’s movement, several thousand people surrounded the venue where PM Chand was meeting with leaders of the NC and ULF and kept the negotiators virtually under siege for several hours. Prime Minister Chand subsequently resigned (Parajulee 2000, 93). On the morning of April 16, King Birendra announced the dissolution of the National Legislature and other Panchayat structures, officially abolishing the Panchayat regime. During the two months of protests, forty-five people had been killed and thousands injured. On April 19, the king invited NC leader K.P Bhattarai to form a transitional government, known as the “interim” government, with a one-year mandate to draft a new constitution, call for elections, and handover the government to a democratically elected government. The interim government included eleven members: PM Bhattarai, three members from NC and three from ULF; two members nominated by the King; and two from independent citizens, Devendra Raj Panday as Finance Minister and Dr. Mathura Prasadh Shrestha as Minster of Public Health. Talking about his appointment, Dr. Shrestha explained,

I was made Minster without my consent. I did not want to join the ministry but Man Mohan Adhikari [ULF] and then Prime Minister K.P. Bhattarai [NC] came and said: for good or bad, we made the decision believing that you would agree (…) But if you don’t join, people may not trust us, they will ask questions and we will have problems or even crises. I joined without actually wanting to join (Shrestha, 2014).

The move to include these two civil society leaders in the transitional government was to make the new government more legitimate vis-á-vis the people. Through taking them on board PM Bhattarai was placing the people’s leaders by the government’s side. The next section assess whether or not pressure from civil society led the governing regime to establish the Mallik commission.

b. Assessing the Existence of Vertical Accountability Relationships as a Result of the Mallik Commission

In this section, I examine whether or not the evidence collected from semi-structured interviews and primary and secondary documentary sources fulfills the evaluative criteria proposed in Table 2.

Vertical Accountability Leading to the Establishment of the Mallik Commission

Evidence gathered suggests that the pressure from civil society led the governing regime to establish the Mallik Commission. On February 25, 1990, one week after the people’s movement began, human rights organizations demanded an immediate judicial investigation into the unnecessary force against demonstrators and strong actions against the persons responsible (Final Report of the Mallik Commission 1990, Preface). On March 1, the Nepal Medical Association issued its first press release, denouncing the killing of demonstrators and torture in detention centers and demanding “that an independent judicial inquiry be instituted and the findings of this commission be made public” (Adams 1998, 96-97). On March 13, 48 writers and poets issued a joint press statement, expressing their rage at torture and killings of protesters and demanding the formation of “an impartial investigation committee to look into these incidents” (Final Report of the Mallik Commission 1990, Preface). As a result, on April 6, newly appointed PM Chand established a commission of inquiry “to investigate into the damages inflicted by the recent incidents in the nation and to submit a report” (Final Report of the Mallik Commission 1990, Preface) with Justice Prachanda Raj Anil as the Chairperson. The Anil Commission was established by the Panchayat government as a response to pressure from civil society.

However, people did not consider the Anil commission legitimate because it had been appointed by Panchayat PM Chand, and they mobilized against it. Moreover, the commission’s mandate only referred to investigating the “damages inflicted” but did not refer explicitly to the killing of civilians. The Chand government only lasted 10 days and, on April 19, the new interim government was formed under PM Bhattarai. The interim government appointed Kapil Shrestha and Prakash Kafle, two representatives from human rights organizations, as commissioners in a move to legitimate the Anil Commission. Their refusal to join along with mounting pressure from civil society led to the resignation of Judge Anil and its members.

On May 23, one week after the dissolution of the Anil Commission, the new interim government led by PM Bhattarai appointed another commission with Judge Janardan Mallik as the chairperson. The mandate of the new Mallik Commission explicitly mentioned investigation into the killings during the movement, the naming of the perpetrators, and advising the government on further actions (Final Report of the Mallik Commission 1990, 1). These developments suggest the interim government was rendered accountable to civil society. Civil society mobilization against the Anil Commission led to its dissolution and the appointment of the Mallik Commission, with a clear mandate to investigate the killings, name perpetrators, and recommend actions.

Vertical Accountability as a Result of the Mallik Recommendations

In their final reports, TCs make recommendations for the governing regime to implement. In case these recommendations are not implemented, civil society can press the government to implement them. I examine whether or not civil society mobilized to implement the recommendations and whether or not this mobilization led to the implementation of the Mallik Commission recommendations.

Civil society mobilization revolved around two main objectives: the official publication of the Mallik Commission’s report, and the prosecution of those responsible. Here, I examine the short and medium-term position of civil society.

Short-term (one year)

On December 31, 1990, the Commission submitted the final report to the interim government. PM K.P. Bhattarai had decided not to act upon the final report, as his interim government had less than four months left in office. Moreover, his main priority was to hold elections, the first democratic elections since 1959. Devendra Raj Panday, then Minister of Finance on behalf of civil society, recalls,

[Prime Minister] K.P. Bhattarai wanted the next elected government to decide on the report. That’s where Mathura, Nilambar [Nilambar Acharya, Minister of Law and Justice] and myself come in: we didn't let him do that. No, it’s our commission! We have people outside, how could I show my face to the human rights community? The Prime Minister’s response was to request the formation of a sub-committee [to decide on the next steps] including the Home Minister, Nilambar and myself. But we never got to do the formal business because the Home Minister was part of the team [the Home Minister was one of the two Ministers nominated by the King]. (interview Panday 2014)

Finally, it was decided to send the Mallik Commission’s report to the Attorney General for implementation. The Decision and Opinion of the Interim Government in relation to the Mallik Commission Report, adopted by the Council of Ministers on February 1, 1991, contained three main decisions (Council of Ministers 1991). The first was to acknowledge the submission of the Mallik Commission’s report and to send it to the Attorney General for further actions. Second, to seize passports and impose a ban to leave the country on all members of the two Panchayat governments to which end the use of excessive force had been authorized. The third decision was to take no action against the Nepal Police on the basis that the police was involved in atrocities due to the faulty system and that the government needed them to hold impartial and peaceful elections. Thus, instead of punishing perpetrators in the police force, the interim government offered an amnesty in exchange for their support to conduct the elections.

The interim government did not officially publish the Mallik Commission’s report. Instead, it was leaked to the media and the newspapers published the main findings. Patma Ratna Thuladar, civil society activist, recalls strong voices from civil society asking for the report to be made public and perpetrators to be punished (interview Thuladar 2015). Nevertheless, the situation had changed and the pressure from civil society was no longer as strong, partly because civil society was directing the pressure towards their government. Mr. Thuladar reflects on this: “The problem was very serious for civil society and human rights groups because the government was run by their own leaders” (interview Thuladar 2015). R.K Mainali points specifically at those leaders who were in the interim government representing civil society: “some civil society activists protested, they demanded the publication of the Mallik report, but they did not organize mass protests against it. Mathura [Dr. Mathura Shrestha] and Devendra [Devendra Raj Panday] were in the Cabinet” (interview Mainali 2015). As well as these two civil society representatives, the political leaders from the NC and the ULF were the people’s leaders also. According to one of the ministers representing civil society, this weakened the civil society as “it became difficult [in 1990] for lawyers, professors, university teachers, school teachers to put pressure on the government, which was NC and ULF, because it is their leaders” (interview Panday 2014).

The first democratic elections since 1959, held on May 12, 1991, further softened civil society’s stand on the Mallik Commission’s report. First, the election campaign weakened civil society, polarized by competing political parties. Second, representatives from civil society and human rights organizations formally became political party members. A doctor who was an activist during the People’s Movement, reflects on the reasons why civil society pressure vanished: “the human rights movement became orphan; after multiparty democracy, people could engage with political parties, so civil society people were recruited as members” (interview Boghendra Sharma 2015). After the 1991 elections, civil society remained divided according to party lines (interview Acharya 2015).

On July 8, 1991, G.P. Koirala, the Prime Minister of the first elected NC government, presented the Mallik Commission’s report to the Speaker of the House of Representatives along with the decision of the interim government, from February 1, 1991, and the advice of the Attorney General, from July 7, 1991, “pointing out that the report was of public importance” (The Independent 1991). In his opinion, the Attorney General had alleged that the Mallik Commission report had failed to specify the legal basis to punish those responsible and had failed to provide enough evidence. Beyond a debilitated civil society, the focus of the government had changed completely. Minister Acharya stressed the need for the first elected government to implement the new constitution and to deal with other priorities. In this new relationship, between the newly elected-government and a palace without official power, the former was not ready to implement the Mallik Commission’s report (interview Acharya 2015).

Medium term (five years)

In August 1992, one and a half years after the submission of the Mallik Commission’s report, the issue of prosecuting those named surfaced again. On August 21, 1992, with mounting pressure from the opposition, Prime Minister G.P. Koirala asserted in Parliament that it was impossible to initiate actions against anyone implicated in the Mallik report without concrete evidence. The opinion of then Attorney General was used again as the rationale for this argument. The statement caused the Commission’s Chairperson Janardan Mallik to publicly state, “[t]he [Prime Minister] himself has not perhaps read the report” (The Independent 1992) and “[t]he [A]ttorney [G]eneral is not the only person who knows about laws, there are people who know even better” (The Commoner 1992). Chairperson Mallik was also quoted by the media as stating, “[t]he report does not lack evidence but the government is not implementing it to protect its own position” (The Independent 1992).

Devendra Raj Pandey and Nilambar Acharya, former Ministers of the interim government, also criticized the Prime Minister’s statement against prosecution, alleging that “by refusing to take action against the Panchayat chiefs who suppressed the historic Jana Andolan through terror and killings, [the Prime Minister’s statement] reflects a lack of intent to consolidate democracy” (The Independent 1992). They further criticized the government for “promoting and rewarding several individuals associated with the previous regime, including those who have been implicated in the Mallik Commission report” and charged against the leadership of the opposition, the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist) party, for “not being firm in its commitment to see that the Mallik Commission report is fully implemented” (The Independent 1992).

The pressure from the public was enough to force the government to respond. As reported at the time, “due to escalating public pressure to implement the report the Prime Minister decided to constitute a ‘study group’ to take up the matter” (The Independent 1992). Radheshyam Adhikari, lawyer and then Member of Parliament for the NC, recalls a meeting of the study group where then Prime Minister G.P. Koirala concluded the meeting saying, “[the Mallik Commission report] is a document of that time. It will be preserved for the history, but now nobody will be prosecuted” (interview Adhikari, 2015). The decision was strongly protested. Patma Ratna Thuladar, then Member of Parliament, recalls, “I myself was in the parliament and some of us shouted very loudly that the commission report should be accepted by the government formally and then [the government] should take strong action against all those named, one by one” (interview Thuladar, 2015).

On July 12, 1994, King Birendra dissolved the popularly elected House of Representatives on the recommendation of Prime Minister G.P. Koirala. During its time in office between June 1991 and July 1994, the NC government did not publish or implement the recommendations contained in the Mallik report. Nonetheless, the report was still a pending issue on the agenda of human rights organizations. Sushil Pyakhurel, human rights activist, recalls, “because we had access to UML [the Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist Leninist)], we lobbied them to put in their manifesto for the elections that if you will be in power, you will do two things: set up a human rights commission and publish the Mallik report; and they agreed” (interview Sushil Pyakhurel, 2014). Thus, the 1994 Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist Leninist) election manifesto stated, on page 30, “the violators of human rights shall be prosecuted according to the law; the reports of the Mallik Commission and Committee to Investigate the Disappeared Persons after 2017 BS (1960) shall be made public and they shall be implemented” (INHURED International 1995, 26).

The Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist Leninist) won the elections in November 1994, securing 88 of the 205 seats, and formed a minority government. However, the new government did not implement the Mallik Commission report. It did not publish it either. It was INHURED International, human rights organization, that photocopied and published the report, making it accessible to the general public in 1994 (INHURED International 1995, 24).2 Interviewees who represent civil society and the human rights movement see the fact that the Mallik Commission report was neither published nor implemented as their failure. They agree that the way civil society was organized around political parties weakened their demand for publication and implementation of the report.

Civil society pressure was not enough for the government to publish the Mallik report or to prosecute alleged perpetrators named in the report. The failed implementation of the recommendations compiled in the Mallik Commission report as a result of civil society mobilization, demonstrates a lack of vertical accountability relationships between civil society and the governing regime.

c. Explaining the Lack of Implementation of Recommendations

As for the failure to implement the recommendations, the main reason for this was the limited pressure from civil society on the government. Civil society pressure, which was very strong before the Mallik Commission was established, became weak after the new governing regime was established. The main reason was the close relationship between civil society and political parties in Nepal. Civil society activists who had been protesting on the streets and calling to punish those who had killed demonstrators, also had their political affiliation. Some of them were political party members. After the ban on political parties was lifted, these activists officially became political party members who had to follow the party discipline. Such party discipline was dependent on the compromise that political leaders had reached with the King, and which excluded any prospect of prosecuting figures from the previous regime. As former Minister Panday explained, talking hypothetically,

I am a human rights person until April 18, 1990; I am associated with Nepali Congress, but I would not say that openly. Once parties were legalized, I could say it openly: I am a party member. Under the party, I have to be under the discipline. When the party people are running the human rights movement, they can’t put as much pressure [on the government]. This constraint is very important. (interview Panday 2014).

A second reason for the softening of civil society mobilization against the government is that it is now their government. The 1990 interim government was the result of civil society and ordinary people’s mobilization through the People’s Movement. People would not organize mass protests against it. Further, this government had included not only the political party leaders, but also the civil society leaders. The following 1991 NC, and 1994 Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist Leninist) governments were the result of democratic elections. It was the people who voted for these parties. This led to limited mobilization against the government.

To conclude, the level of the pressure that rendered the governing regime accountable to the demands of civil society before the commission was established, did not exist when the time came for civil society to mobilize for the implementation of recommendations. I have identified two reasons for this lack of pressure. First, the close relations between civil society and political parties in Nepal; and, second, the fact that, with the new regime in government, civil society had to protest now against their government, the one they had fought to establish. Later on, the celebration of the first democratic elections further softened civil society’s stand on the Mallik Commission’s report as civil society became polarized along political party lines.

3. Case Study: The 1994 Zonal Commissions in Sri Lanka

The section on Sri Lanka follows the same structure as the previous. First, I present the context of the 1994 transition and the role of political parties and civil society. Next, I assess the existence of vertical accountability relationships as a result of the Zonal Commissions. Finally, I explain the possible reasons behind the lack of implementation of the commission’s recommendations.

a. The 1994 Transition and the Role of Political Parties and Civil Society

In 1987, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) (People’s Liberation Front), a radical leftist armed group, lunched its second armed insurgency against the Sri Lankan government, at the time, under the United National Party (UNP). This armed insurrection affected mainly the South and Central part of the country. The response of the state security forces was brutal. Estimates indicate around 50,000 people were killed or disappeared during the two years of JVP armed insurgency, known as the years of terror. At the same time, the Government of Sri Lanka was fighting the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in the North and Eastern part of the country. On June 11, 1990, the ceasefire agreed between the LTTE and the UNP Government broke after the LTTE massacred 600 police officers. The police massacre started the Eelam War II, which lasted until January 1995. In November 1994, Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga won the presidential elections under the People’s Alliance, a platform of leftist and minority parties in the opposition, signaling the end of seventeen years of UNP government, which had turned extremely repressive.

During the years prior to the victory of President Kumaratunga, the relations between victims, civil society and the political parties in the opposition became very close. In Sri Lanka, the human rights campaign to find the whereabouts of thousands of people who had been forcibly disappeared became the thrust that united victims and human rights organizations with the political parties in the opposition. The campaign against enforced disappearances became a political campaign to defeat the UNP, in office since 1977. I examine these relations next.

The Relation Between Political Parties and Victim Groups

The link between victims and political parties originated from the despair of families to find their disappeared. This desperation led Wijayadasa Pathirana, whose son Sudath had disappeared, to contact Vasudeva Nanayakkara, a Member of Parliament for the Nava Sam Samaja Party (NSSP), a party in the opposition, after having exhausted all other options. Vasudeva Nanayakkara and Vickramabahu Karunarathna, the NSSP leaders, had formed an underground organization collecting information concerning the disappeared. Karunarathna recalls that he started working on this cause because, “parents would come to our places and tell us, assuming we had some contact with people taken into custody, and we intervened. That is how we got into the process as politicians. By 1989, insurgency was over, but large numbers were getting arrested, so we continued” (interview Karunarathna 2015).

In April 1990, Wijayadasa Pathirana established with the support of the NSSP leaders, Nanayakkara and Karunarathna, the Organization of the Parents and Family Members of the Disappeared. The organization had four major demands for the government; 1) appointing independent commissions to establish the truth, 2) punishing the perpetrators, 3) compensating the family members, and 4) releasing the political prisoners (interview Pathirana 2015).

According to a civil society activist, the initial work by Nanayakkara and Karunarathna of the NSSP to increase the opposition against disappearances strengthened the main opposition party, the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). “Mahinda Rajapaksa was then a friend of Vasudeva [Nanayakkara]. I suppose he [Rajapaksa] was politically smart enough to position himself there, knowing that people were disappearing from his area, to link up and begin to support [the] NSSP to raise these issues” (interview Nimalka Fernando, 2015).

On July 15, 1990, the first branch of the Southern Mothers’ Front was inaugurated in the southern district of Matara under the auspices of Mahinda Rajapaksa and Mangala Samaraweera, both SLFP’s Members of Parliament. Around 1,500 women from the Matara district attended the meeting to elect office bearers to coordinate the work of the group. Within six months, branches had been established in 10 other districts under the patronage of Members of Parliament of the SLFP from the respective area (Alwis 2008, 154).

On February 19, 1991, the Southern Mothers’ Front held its first convention at the Town Hall in Colombo. The 10 resolutions passed unanimously at this meeting, called, among others,

2. That the government appoint a fully powered independent Commission, free from state interference and including Supreme Court Judges, to verify the facts around arbitrary arrests and detention.

3. That the government pay compensation to the dependents of the disappeared as well as for damage of house and property.

5. That the government issue death certificates to the dependents of the disappeared and alleviate their trauma (De Mel 2001, 245).

After the meeting, the first national rally was held with over 15,000 people attending (Alwis 2008, 169). Addressing the mothers at the rally, Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu, the mother of assassinated journalist Richard de Soyza, emphasized that the Southern Mothers Front would act as a peaceful watchdog on whatever government was in power. Nevertheless, she did indicate the organization’s linkage with the SLFP as a measure of protection, given the insecurity at the time. The narrow focus of the Southern Mothers’ Front on disappearances in the context of the political violence in the South between 1987 and 1990, in addition to its close links to the SLFP, led to the appropriation of the organization and its demands by the party. The SLFP eventually used the Southern Mothers’ Front to overthrow the UNP government and secure political power (Samuel 2006, 21). The mothers of the disappeared had managed to create a space for protest, under the organizational umbrella of the Southern Mother’s Front, at a time when dissenting voices were suppressed. Nevertheless, this space was then captured by the SLFP for oppositional politics. Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, the Prime Ministerial candidate for the People’s Alliance, a front of political parties formed to defeat the UNP, captured the mothers’ grief for political purposes during the campaigns for the August 1994 general elections. As Alwis writes,

Herself a grieving widow and mother, she cleverly articulated the mothers’ suffering as both a personal and national experience; she too “sorrowed and wept” with them but also made it clear that she was capable of translating her grief into action, of building a new land where “other mothers will not suffer what we suffer” (Alwis 2008, 170).

There is a shared understanding among human rights practitioners that political party leaders in the opposition at the time “had ‘used’ or ‘hijacked’ the movement against disappearances, especially the organizations of mothers and families of the disappeared, to consolidate their own political bases” (Wijewardene and Nagaraj 2014, 97). The Southern Mothers’ Front disintegrated with the electoral victory of the People’s Alliance (Samuel 2006, 22). The November 1994 elections resulted in Kumaratunga becoming the 5th President of Sri Lanka. The two SLFP leaders who also belonged to the Southern Mother’s Front, Mahinda Rajapaksa and Mangala Samaraweera, became the Minister of Labor and Minister of Post and Telecommunications, respectively. Being dependent on the SLFP for its leadership, the Southern Mothers’ Front could not convert itself into a politically independent watchdog body envisaged by Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu (Samuel 2006, 23).

The Relation Between Political Parties and Human Rights Groups

As in the case of victims, civil society also engaged with political party leaders as they offered protection. According to a human rights activist, the engagement of the civil society with the political movements began at the period of terror between 1988 and 1989. Political parties could offer protective cover when civil society activists were threatened. Such protections by political parties were offered in two ways. First, Members of Parliament were in general guarded by the police. The then President J.R. Jayawardena had also provided arms to those who supported the July 1987 Indo-Sri Lanka Peace Accord, including Vasudeva Nanayakara and Vickramabahu Karunarathna of the NSSP (interview Nimalka Fernando, 2015). Because of this security protection offered to Members of Parliament, civil society had them engage in activities that could run certain risks. For example, in September 1990, NSSP Vasudeva Nanayakara and SLFP Mahinda Rajapaksa attended the 31st session of the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance in Geneva and described, to the world, the atrocities that were taking place in Sri Lanka. At the airport in Colombo, the police confiscated the 533 documents Rajapaksa was carrying that contained information about missing persons and 19 pages of photographs. Nonetheless, he was allowed to travel to Geneva, attend the working group session, and share the detailed accounts of the atrocities perpetrated by the UNP government (Bastians 2014).

Civil society support to Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s election campaign in 1994 was crucial to understand the relation between civil society and the political parties in the opposition. A recent study that examines the evolving relationship between political parties and human rights activists in Sri Lanka refers to “significant sections of the community of human rights practitioners being closely involved in supporting the election of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga as President” (Wijewardene and Nagaraj 2014, 95). Similarly, many of the people I interviewed referred to civil society involvement in Kumaratunga’s campaign. One of the interviewees explained,

So you got a situation in which civil society in this country, which by and large in terms of those working on human rights, democracy and all of that, has a kind of left orientation, had absolutely no hesitation in being sympathetic supporters or, in fact, part of the Chandrika campaign. (interview Saravanamuttu 2014)

Another interviewee expressed, “it’s not that you have independent civil society just waiting somewhere, like in cold storage, until the change happens and when change happens they are called. No, they were part of the campaign” (interview Gunawardena 2014).

Human rights activists’ involvement went beyond the electoral campaign; they also became engaged in the Kumaratunga administration, formally or informally (Wijewardene and Nagaraj 2014, 95). This involvement of activists with the administration blurred the distinction between civil society and the government. Consequently, the rules of engagement between human rights practitioners and the state changed during the time of Kumaratunga in ways that human rights practice “was seen as more muted and domesticated’ (Wijewardene and Nagaraj 2014, 96). As one of the interviewees noted, “civil society was not as critical with the government as it ought to have been.” (interview Saravanamuttu 2014)

The result was a government that had come to power with the support of victims and human rights activists and that was now in a position to silence the same people. As a women’s rights campaigner explained, “women of the Mothers’ Front were compromised by compensation and jobs given by the new [People’s Alliance] government when it came to power” (Dulsie de Silva, interview quoted in Thomson-Senanayake 2014, 225). It was not only the Southern Mothers’ Front that were compromised, human rights practitioners were too. As Thomson notes,

Concerns were also raised that many within the human rights community had compromised their independence by publicly lending their support to the [People’s Alliance] and even securing government positions. They found themselves in a weakened position at the very moment the People’s Alliance should have been called to account to realize its election promises. (Thomson-Senanayake 2014, 226)

The next section assesses the existence of vertical accountability relationships as a result of the Zonal Commissions.

Vertical Accountability Leading to the Establishment of the Zonal Commissions

If the pressure from civil society leads the governing regime to establish a TC, the state is being made answerable to civil society demands. I sustain that victims and civil society demands led the government to establish the Zonal COIs. The demand to establish a COI to look into disappearances was a victims’ demand. As early as February 1991, the Mothers Front had unanimously passed a resolution calling the government “to appoint a fully powered independent Commission, free from state interference and including Supreme Court Judges, to verify the facts around arbitrary arrests and detention” (de Mel 2001, 245). However, the UNP government rejected the establishment of any COI to look into disappearances during the years of terror, from 1988 to 1989, when 50,000 people had allegedly been forcibly disappeared. Instead, in 1991, the UNP government established a COI to look into disappearances happening in the following twelve months, involuntary removals that had not yet occurred. A new Commission was appointed in 1992 and 1993 with the same mandate (Law & Society Trust 2010, 20). After President Premadasa was assassinated on May 1, 1993 by an LTTE suicide bomber, new President Dingiri Banda Wijetunga revoked the warrants of the previous three commissions. In August 1993, he appointed another Commission to investigate involuntary removals of persons during the period between 1991 and 1993. None of the reports of these four commissions were made public (Law & Society Trust 2010, 24). It was against this background of the UNP government opposition to investigating disappearances during the 1988-1989 period, that the 1994 elections took place.

In both the parliamentary elections in August 1994 and the presidential elections in November 1994, the People’s Alliance, a platform of leftist and minority parties in the opposition, was contesting the elections promising investigation into disappearances. Specifically, the then opposition leader Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga promised a thorough investigation into disappearances and speedy actions on past human rights abuses (Commission of Inquiry 1998, Introduction). After the victory of the People’s Alliance at the parliamentary elections in August 1994, the new government began the task of appointing three Zonal Commissions to investigate disappearances since 1988 (Commission of Inquiry 1998, Introduction). However, the government could not establish the COIs because of the disagreement by the UNP President who argued against their establishment (Commission of Inquiry 1998, Introduction).

During the three-month interval between the parliamentarian and presidential elections, the Prime Minister’s Office under Kumaratunga’s direction, had responded to letters sent by relatives of the disappeared. The Office promised that, in case of winning the Presidential elections, the new President would appoint a COI into disappearances and that measures would be taken to pay compensation to the affected families (Interim Reports of the Southern COI 1997, 37-39). The establishment of the COI, not possible under a UNP President, and the payment of compensation to all those victimized became, once again, a central issue during the November 1994 Presidential elections. On November 30, 1994, only 18 days after winning the elections, new President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga issued the Presidential decree establishing the three COI. In doing so, the new governing regime became answerable to the citizens.

Vertical Accountability as a Result of the Zonal Commissions’ Recommendations

The three Commissions made extensive recommendations dealing with reparations. Among others, they recommended the payment of economic compensation to the relatives of the disappeared. In practice, the amounts the government provided were less than those recommended by the Commissions and most of the other recommendations intended to redress victims were not implemented. Recommendations to collect information on the location of mass graves and identities of bodies alleged to be buried and to exhume burial sites were not implemented.

The COIs also recommended the prosecution of perpetrators. Following recommendations by the Southern and Central Commission, the Government established in November 1997 the Disappearances Investigation Unit (DIU). It also established, in July 1998, the Missing Persons Commissions Unit (MPU) (the unit in charge of cases of disappearances within the Attorney General’s office). The police DIU investigated thousands of cases on the basis of the outcome of the fact-finding carried out by the Commissions, which led to the Attorney general’s MPU starting criminal proceedings against 597 security forces personnel. However, only 12 perpetrators out of 597 security forces personnel prosecuted were convicted as of 2004, most of them junior officers. Finally, the government did not implement most of the COIs recommendations intended to remove perpetrators from public office or to adopt institutional or legal reforms to avoid repetition.3

Despite that fact that most of the recommendations the Commissions made were not implemented, victim groups and civil society in Sri Lanka did not press the governing regime to do so. Only in one instance, the Secretary-General of the Organization of the Parents and Family Members of the Disappeared filed a case against the Deputy Inspector General circular directing the reinstatement of all officers who had been interdicted and charged in courts, but subsequently bailed out. In response to the writ, the Court quashed the circular on the grounds that officers against whom criminal proceedings had started should not be reinstated (Law & Society Trust 2010, 94, footnote 124). Other than that, there was no pressure from victims or civil society on the governing regime to implement the Commissions’ recommendations. Even if such pressure had existed, it was not enough to render the governing regime accountable to the demands from victims and civil society. Consequently, there were no vertical accountability relationships between civil society and the governing regime as a result of the Commissions’ recommendations.

c. Explaining the Lack of Implementation of Recommendations

The analysis above shows a governing regime that is held to account by civil society and victims to establish a COI but this same civil society did not exert pressure on the governing regime to implement the Commissions’ recommendations.

The Sri Lankan case indicates that close relations of victims and civil society with political party leaders prior to the establishment of a commission, could have detrimental consequences for a long term-success of a TC as the former cannot effectively pressure the government to act on its recommendations. Concerning victims, the political leaders on whom victims needed to put pressure were the same leaders who had founded the victims’ movements. The president of a victim’s organization noted that political leaders had led the victims’ movement since the beginning and those same leaders became part of the government. As he expressed,

When political leaders who had supported victims became Ministers, their [the victims’] heroes are in the government. And they are promising and the promises are being implemented, the Commissions are coming, the Commissions are listening and there were very few cases coming out. So the people just thought they would do something. (…) We thought good results will come, in fact good results came, but no one pushed those recommendations to be implemented against the government. That was the main problem. (interview Brito Fernando 2014)

Others refer to political party leaders “using” or “hijacking” “the movement against disappearances, especially the organizations of mothers and families of the disappeared, to consolidate their own political bases” (interview with human rights practitioners in Wijewardene and Nagaraj 2014, 97). The Organization of the Parents and Family Members of the Disappeared legal advisor recalls meeting with President Kumaratunga. “We submitted a memorandum asking for the recommendations to be implemented. But then, the leaders forgot all the promises they had made.” (interview Kumarage 2015)

Concerning the role of civil society, there is an understanding that there was no pressure on the government to implement the recommendations. As a human rights lawyer, expressed,

From my perception and my recollection, there was no pressure at all. There was not pressure and, therefore, [the government] was allowed to get away with not implementing or just ignoring the recommendations and just focusing on paying some money and that was it. (interview Pinto-Jayawardena 2014)

There is also an understanding that the lack of pressure was linked to the close relationship between civil society and the government of President Kumaratunga. Particularly, human rights practitioners were “closely involved in supporting the election of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga as president and engaged in her administration, formally or informally” (Wijewardene and Nagaraj 2014, 95). As a member from civil society reflected,

In Chandrika’s time, resistance was not possible because everyone was a friend. Everybody who worked with her was a friend (...) So civil society became weak during Chandrika’s time, our autonomy could not be safeguarded. We became part and parcel of that process. (interview Nimalka Fernando 2015)

4. Conclusions

Both cases show pressure by civil society and victims was limited when their governments did not implement the Commissions’ recommendations. In Nepal, limited pressure was due to the fact that civil society had been absorbed by the system and, when the time to implement the recommendations came, civil society was part of the governing regime. With the legalization of political parties, civil society activists formally became political party members who had to follow the party discipline. Such party discipline was constrained by the compromise political leaders had reached with the King, which excluded any prospect of prosecuting figures from the previous regime. The public’s reluctance to organize mass protests against their elected government, the one they had fought for, also contributed to low levels of pressure.

Similarly, in Sri Lanka, civil society and victim groups did not press the governing regime to implement the Commissions’ recommendations. This was due to the close relationships between victims, civil society representatives, and political leaders who became part of the new governing regime. These political leaders had founded the victims’ movements. As for civil society activists, they had been actively involved in supporting the election of President Kumaratunga. When the time to put the pressure on arrived, many within civil society were not monitoring the new government. Instead, they had become engaged, formally or informally, in the new administration.

Both cases, Nepal and Sri Lanka, show that relations between victims, civil society and political parties leading to the establishment of a commission, hindered social mobilization for the implementation of recommendations. In Nepal and Sri Lanka, the internal dynamics explain and frame the limited or complete lack of mobilization in support of the implementation of the commissions’ recommendations.