Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

versión impresa ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.15 no.1 Bogotá ene./jun. 2013

English as an International Language: A Review of the Literature

Inglés como lengua internacional: revisión de la literatura

Raúl Enrique García*

Licenciatura en Ingles

Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia

E-mail: raulspot3@gmail.com

*Raul Enrique García lópez, Linguistics, Teacher Education, Critical Discourse Analysis and ITC for Teaching. Raul Enrique Garcia is an Assistant Profesor at Universidad Industrial de Santander. He has an MA in English Studies from Illinois State University and a BA in English Philology and Teaching from Universidad Nacional de Colombia. His research interests include English as an International Language/English as a Lingua Franca, Applied

Received: 28-Feb-2013 / Accepted: 22-May-2013

Abstract

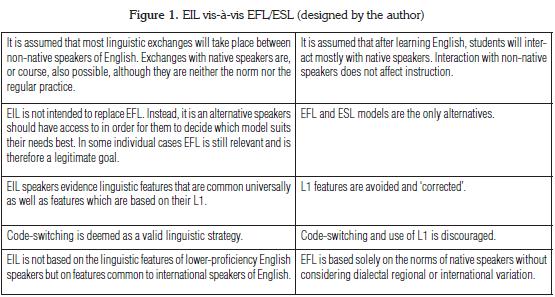

This article critically reviews and discusses English as an International Language (EIL) as an alternative to the traditional models of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and English as a Second Language (ESL). The author suggests that the model of EIL is an alternative worth- discussing in the Colombian context. The article is divided into four different sections: a) EIL, ownership of English and native-speakerism, b) attitudes towards EIL, c) EIL described: What does it look like? and d) EIL and English teaching. The review of the literature evidences that there are still many heated debates on the sociocultural aspect of EIL, that one of the greatest challenges of EIL is the attitudes of English teachers and speakers towards the use and legitimization of non-standard varieties, that there is still much to be done in terms of the description of EIL and that adopting an EIL perspective would imply transforming the ways English is taught. The article concludes with an invitation to the ELT community to initiate the discussion of the potential application of EIL in the Colombian context.

Key words: English as an International Language, English as a Lingua Franca, English in Colombia, Native-speakerism, Non-native speakers and teachers of English.

Resumen

Este artículo discute la literatura más relevante en el modelo de Inglés como Lengua Internacional (EIL por su sigla en inglés) como una alternativa a los modelos de Inglés como Lengua Extranjera (EFL) e Inglés como Segunda Lengua (ESL). El autor propone que el modelo EIL es una alternativa digna de ser discutida en el contexto colombiano. El texto se divide en cuatro secciones: a) EIL y las nociones de propiedad de la lengua y hablante nativo, b) actitudes hacia el modelo EIL, c) descripciones del modelo EIL, d) EIL y la enseñanza del inglés. La revisión de la literatura evidencia que existe mucha controversia sobre los aspectos socioculturales de EIL, que uno de los más grandes retos del modelo EIL es las actitudes de profesores y hablantes hacia el uso y legitimación de variedades no-estándar de inglés, que hay mucho por hacer en términos de la descripción del modelo EIL y que la adopción de un modelo EIL implicaría transformar las maneras como se enseña el inglés actualmente. Este artículo termina con una invitación a la comunidad ELT en Colombia a iniciar una discusión acera de la posible aplicación del modelo EIL en el contexto local.

Palabras clave: Inglés Como lengua internacional, Inglés Como lengua franca, Inglés en Colombia, hablantes não Nativos y profesores de Inglés.

Résumé

Cet article est une discussion sur la littérature la plus importante sur le modèle de l'Anglais comme Langue Internationale (EIL, par sa sigle en Anglais) en tant qu'alternative aux modèles de l'Angles comme Langue étrangère (EFL) et l'Anglais comme Seconde Langue (ESL), L'auteur propose que le modèle EIL est une option digne d'être discutée dans le contexte colombien. Le texte est divisé en quatre sections: a) EIL et les notions de propriété de la langue et locuteur natif; b) attitudes vis-à-vis du modèle EIL; c) descriptions du modèle EIL; d) EIL et l'enseignement de l'Anglais. La révision de la littérature met en relief: qu'il existe une énorme controverse sur les aspects socioculturels de l'EIL; qu'un des plus grands défis du modèle EIL sont les attitudes des enseignants et des anglophones vis-à-vis de l'usage et de la légitimation de variétés non standard de l'Anglais; qu'il y a beaucoup à faire en ce qui concerne la description du modèle EIL et que l'adoption d'un modèle EIL entraînerait une transformations des manières dans lesquelles l'enseignement de l'Anglais est fait aujourd'hui. Cet article finit avec une invitation à la communauté ELT en Colombie à entamer une discussion sur l'application éventuelle du modèle EIL dans le contexte local.

Mots clés: Inglés Côme lengua internacional, Inglés Côme lengua franca, Inglés en Colombie, hablantes pas nativos y profesores de Inglés

Resumo

Este artigo discute a literatura mais relevante no modelo de Inglês como Língua Internacional (EIL pela sua sigla em inglês) como uma alternativa aos modelos de Inglês como Língua Estrangeira (EFL) e Inglês como Segunda Língua (ESL). O autor propõe que o modelo EIL é uma alternativa digna de ser discutida no contexto colombiano. O texto se divide em quatro seções: a) EIL e as noções de propriedade da língua e falante nativo, b) atitudes em relação ao modelo EIL, c) descrições do modelo EIL, d) EIL e o ensino do inglês. A revisão da literatura evidencia que existe muita controvérsia sobre os aspectos socioculturais de EIL, que um dos maiores retos do modelo EIL é as atitudes de professores e falantes em relação ao uso e legitimação de variedades não padrão de inglês, que há muito por fazer em termos da descrição do modelo EIL e que a adoção de um modelo EIL implicaria transformar as maneiras como se ensina o inglês atualmente. Este artigo termina com um convite à comunidade ELT na Colômbia a iniciar uma discussão sobre a possível aplicação do modelo EIL no contexto local.

Introduction

'Far more people learning English today will be using it in international contexts rather than in just English-speaking ones' (Seidlhofer, 2011, p. 17). This seems to be an incontestable fact, especially if we think about the unprecedented number of English learners across the world, a number that supersedes that of speakers of English as a first language. In times when learning English has become mandatory and very aggressively promoted in many educational systems, the number of English learners has reached unprecedented peaks. This is particularly true in many countries in the expanding circle (Kachru, 1985) such as Colombia. However, it is very difficult to imagine that the thousands of students learning English today in Colombian schools will use it on an everyday basis with L1 speakers of English. On the contrary, it seems that those who will actually make use of it will do so in international contexts where English is normally used by multilingual speakers whose first language is other than English.

Still, as Seidlhofer (2011, p. 17) points out, there has been little impact into the research of the acquisition of international English. Even though English as an International Language (EIL) is now regarded as a legitimate alternative to the traditional English as a Second Language (ESL)/English as a Foreign Language (EFL) dichotomy, and has gained space in the scholarly discussion, research on its impact on language teaching has not moved in the same direction, at least not at the same pace. In the Colombian case, the EFL alternative has remained largely unchallenged. A review of the literature of the most relevant journals on English teaching in the country shows that only Macías (2010) has suggested EIL-ELF as an alternative for the Colombian context. In his article, Macías proposes English as a Lingua Franca as an alternative to the Colombian context for two chief reasons: a) as a way to avoid the resistance Inner Circle varieties sometimes face in settings like Colombia and, b) to provide learners and teachers with more opportunities to understand the transformations that English has gone through due to its global expansion. The impact of this, Macías argues, would result in local experts and teachers playing a more active role in the design and implementation of teaching and learning theories and materials –including textbooks- that would incorporate local realities and therefore respond more effectively to local needs. In any case, the sure-to-widen debate about the nature of teaching English on a global scale is especially relevant in Colombia in times when the National Bilingual Program (NBP) seems to have succeeded in, at least, fostering discussion and controversy around English teaching policies in Colombia. Much of this controversy has revolved around the role of the British Council, an agency from the inner circle, in advising the Colombian Ministry of Education (Gínzalez, 2007).

In Colombian, a review of the journals on the teaching of English evidences that the EFL model is taken for granted by most scholars. This is also the case for the NBP, which states: 'In the Colombian context, and for the scope of this proposal (the Colombian Standards for English Teaching) English is understood as a foreign language...' (Ministerio de Educación, 2006, p. 5). If we limit ourselves to choose between an EFL and an ESL model, it is then very clear that the former is the most suitable approach for the Colombian context. However, it is the very same adoption of this dichotomy what seems to be debatable. Increasingly, scholars (Graddol, 2006; Crystal, 2004, Jenkins, 2000; 2007, Seidlhofer, 2011; Kirkpatrick, 2010) have noted that most of the interactions in English take place between non-native speakers of English or in contexts where native speaker norms are not relevant. As a consequence, Graddol (2006) points out that the EFL and ESL models have become out-of-place in times when international mobility and communication have become accessible to a larger number of people and where the reasons for learning English have become less associated with a desire to function like a native speaker. In the EFL model, the learner is constructed as an aspirant to the society of the foreign language. Unfortunately, many learners, although competent in the foreign language, fail to acquire the language at a native proficiency level. Therefore, they end up being looked down upon as imperfect speakers who cannot achieve the linguistic and social standards of the native community.

The ESL model has also become irrelevant for many learners since it was designed for post-colonial contexts and immigrant populations. In the former case, the ESL context emerged during the 19th century as a tool used by the British to educate a workforce required for ruling the colonies without the presence of a significant number of British citizens. This elite was not only taught the language, but was also acculturated with a sense of admiration for the culture and life of the British. In this model, the teaching of English literature and arts proved particularly effective in achieving this purpose. It is not a coincidence that the teaching of English literature was first introduced in India and later on in England itself (Viswanatha, 1989).

In the case of immigrant populations, the ESL model refers mainly to the US and other English- speaking countries that receive numerous waves of immigrants. Here, the main goal is to provide learners with the tools necessary to take part in society on an everyday basis, mainly at the administrative and educational levels and/or to facilitate the integration of learners into the mainstream of society. In this model citizenship and civil education both play an important role in the curriculum (Graddol 2006, p.85).

Clearly, none of these models is useful when addressing the use of English in international settings where cultural and social integration are not at the center of English learning, the nature of linguistic interactions is somewhat different and the need to acquire native speaker norms is less relevant. It is in this context that the model of EIL emerges. As English has started to be conceived by some scholars as a language that is not necessarily connected to 'inner circle' countries local varieties have gained recognition. It has become clear that the field of ELT needs to be revised.

In the light of these of facts, the purpose of this review of the literature is to present an overview of the discussion that has taken place during the last 25-30 years on the nature of EIL. By doing so I intend to contribute to the discussion of these matters within the ELT community in Colombia and Latin America, a region that has largely failed to join the global discussion on EIL (Jenkins, 2006) . It is my belief that EIL is worth discussing in the Colombian context. It seems that by bringing the topic to the table we may be able to challenge the assumptions made by the EFL and ESL models and to acknowledge the fact that these models must not remain unquestioned given the sociocultural realities of the use of English at a global level.

In order to do this, I will focus on four different themes that are easily identifiable in the EIL literature: a) EIL, ownership of English and native-speakerism, b) attitudes towards EIL, c) EIL described and d) EIL and English teaching. This is, of course, a subjective taxonomy but I hope it will offer a coherent theoretical framework to start addressing these issues.

This review is intended for E LT/TESOL practitioners and scholars in Colombia interested in the phenomenon of EIL and its applicability in local contexts. It should be understood as a starting point for those who wish to become acquainted with EIL and are in need of a brief compilation of the most relevant literature.

EIL, ownership of English and native-speakerism

In EIL the notion of the native speakers as owners of English is constantly challenged. In this respect, advocates of EIL can be said to be adherents to Kachru's (1985) proposal of the three concentric circles. Kachru's World Englishes can be interpreted as an attempt to recognize varieties of English outside inner circle countries as the materialization of the pluricentrality of English rather than as deviant or interlanguage forms that need to be corrected. It is very common to encounter multiple references to Kachru's circles all over in the EIL literature. In fact, Jenkins (2007, p.17) admits that EIL '...sits more comfortably within a World Englishes framework...'. Jenkins continues to argue that it does so because the model's inherent pluricentrality. Pluricentrality is an essential notion for our purposes since it allows a focus on a selection of norms from many Englishes instead of a variety of English based only on one or two localized varieties. Jenkins continues to make clear that EIL is not to be understood as a model of a supranational standardized variety. Instead, she proposes that EIL is a model that celebrates linguistic diversity, includes multilingual and multi-dialectal features, and provides room for the establishment of local linguistic forms.

The main reasoning of those who promote EIL is that the majority of users of English are not native speakers of the language. This calls for a reconceptualization of what English is and the abandonment of the belief that native-speakerism should be regarded as the norm for English teaching and its methodology (Holliday, 2005, p. 6). Widdowson (1998, p.245) takes a much more impassioned stance by asserting that EIL 'means that no nation can have custody over it...It is not a possession which they (inner circle nations) lease out to others, while still retaining the freehold. Other people actually own it.' In other words, the native speaker is no longer the exclusive model for language learning and use. Thus, the EFL/ESL models must not be considered the only available approaches in countries in the expanding circle where the native speaker has been traditionally endowed with a sense of authenticity and authority. In these settings, genuine English is commonly believed to be that of the speakers of the most prestigious varieties of English. In the EIL model learning native norms is not at the center of learning because the reality of interactions in English does no longer only involve communication with native speakers and due to the fact that the ownership is not attributed only to native speakers. Instead, there is need to develop skills that allows speakers to interact with international users of the language.

Seidlhofer (2011, p. 35) calls our attention to the fact that the tenet of native-speakerism in English learning assumes that intelligibility would be at stake, were we to abandon it. However, she signals the fact that intelligibility is influenced not only by language skills but also by perceptions of the other. She asserts that the way we see interlocutors, whether we identify them as members of our own social or ethnical groups affects our expectations in linguistic exchanges and plays a role in the degree to which speakers understand each other. Intelligibility is then not exclusively a linguistic phenomenon but also a social one. Consequently, giving the EFL model the central role in English teaching is perpetuating the othering of those who are not L1 English speakers. Maintaining such status quo represents, in certain cases, a burden in language teaching, because intelligibility is mediated not only by linguistic performance but also by unalterable, intrinsic features of the language learner such as his/her ethnicity and position in power structures. On the contrary, EIL proposes a model that conceives non-native speakers of English as legitimate users of the language regardless of where they stand in terms of native-speakerism, ethnicity, or even linguistic skill. In this sense, overthrowing the alleged superiority of the native speaker in international uses of English may result in better and more successful communication.

The problem of native-speakerism is also addressed by Hollyday (2005). According to Hollyday, the predominant view of the native speaker as owner of the language is part of a wider phenomenon labeled culturism, which is continuously reified not only by those who are favored by it, but also by those on the periphery of English learning. This reification is part of an equation that finds its origin in an essentialist worldview that assigns a particular culture (and all elements contained in it: religion, language, worldviews) to a specific geographical space. This essentialism, together with the lingering effects of a colonial era and the inevitable dichotomy that emerges between the self and the other anywhere two cultures clash, leads to the imposition of monolithic categorizations that, in language learning, result in the perpetuation of native-speakerism.

However, the EIL model has also been contested by various authors. For some, although it is arguable that EIL does provide learners with agency and control over their learning processes while challenging native-speakerism, it is necessary to look at the bigger picture. What is implied by international? Who determines what may or not enter this realm? Why? Who benefits from it? Pennycook (1994, p.38) addresses these questions and also calls our attention to what he calls the 'two ubiquitous myths of the EIL discourse': the neutrality of English and the belief that English as the world's International Language is a natural occurrence. In regards to the latter, Pennycook reminds us that, instead, EIL is a historically and politically situated occurrence. He argues that English is not an international language per se; no language is. English has become an international language as the product of historic circumstances. To think that the establishment of EIL is a natural consequence in history is to ignore these facts. It is, he asserts, to ignore that the learning and teaching of English serves both to guarantee the influx of capital towards 'inner circle' countries and to continue the dissemination of the value systems and beliefs of these countries to maintain cultural imperialism. Evidence of this is that even though the EIL model has been developing for at least three decades now it is hard to deny that 'inner circle' agencies and scholarship still play the main role in the spread of English in 'outer circle' and 'expanding circle' countries. Second, it is paramount to remember that, even though it can be said that English has transcended the regional borders historically assigned to it and is used by citizens from all over the world, it is not a language void of ideologies, both contemporary and historical. In fact it is necessary to acknowledge that it is impossible to rid any language of the ideologies and histories that have shaped it (Pennycook 1994, p. 9).

Pennycook takes this argument further by asserting that EIL does nothing but reify these myths. He criticizes perspectives such as Word Englishes and EIL because, according to him, they are inclusionary only in appearance, since they perpetuate the idea of monolithic language ideologies, normally attributed to imperialistic endeavors, only that they do so at the nationalistic level. He signals that the Word Englishes perspective does not provide room for intra-national variation. In general, he calls for a demythologization of English that involves rejection of the WE and EIL paradigms. In his own words:

The myth(s) of EIL erase the memory that English is a fabrication, that languages are inventions and that talk of English as an international language is a piece of slippage that replaces the history of this invention with a belief in its natural identity. The myth of EIL depoliticizes English, and does so not by ignoring English but by constantly talking about it, making English innocent, giving it natural and internal justification, a clarity that is not that of a description but an assumption of fact. The myth of EIL deals not merely with the invention of English, but with the strategies that constantly keep that invention in place, with the relentless repetition of the stories and tales about this thing we call English. We need to disinvent English, to demythologize it, and then to look at how a reinvention of English may help us understand more clearly what it is what we are dealing with here (2007, p. 109).

Phan (2008, p.76) adds to this critique of the EIL model by bringing up again the question of native- speakerism and ownership of the language. In this respect he acknowledges that EIL celebrates globalization but also argues that, regardless of how international the setting of communication is, English is still used to exclude and to construct an inferior other. To him, the norms of the native speakers are prevalent over those of the non-native. As an example of his argument, he cites McArthur (1998) to say that no matter how many varieties emerge; Standard English will be on top. As an example he points out that African American English, even though well- established and globally recognized, is still looked down upon in formal settings and institutions.

Speaker and ELT practitioners' attitudes towards EIL

One of the main challenges the EIL model seems to face is the way it is perceived, not by students or authorities, but by teachers themselves. Coskun (2011), in a research study of the attitudes of forty-seven pre-service teachers in Turkey, found that, although these pre-service teachers considered intelligibility to be the central goal of English learning, they reckoned that it is best to teach a normally recognized standard such as American or British English. They also favored the teaching of native prestigious varieties and disregarded non-native varieties as possible alternatives in the ELT classroom. They preferred instructional materials to be written in the American and British varieties. Finally, they evidenced a very low tolerance to errors, understood as forms deviant of the standard varieties.

In a similar study, Fauzia and Qismullah (2009) collected data from ten informants from Asia, six of which were English teachers, and found that the attitudes of most participants towards their own accents in English were favorable. However, when asked what varieties of English they liked the most, only one answered that her own accent was her favorite. The others responded they were keener on the British and American varieties. When asked the varieties of English that they thought should be taught, informants responded 'Standard English' because they considered it to be original and correct English. This is very small sample to be considered representative. Still, it is somehow intriguing that even though speakers are aware of and comfortable with their own accents, they still champion the teaching of standard varieties. This double-standard approach is what Jenkins questions (2000, p. 160) when she asserts that 'There really is no justification for doggedly persisting in referring to an item as 'an error' if the vast majority of the world's English speakers produce and understand it'. In the case of this study it seems clear that the accents of the informants are probably very common in the regions of Asia where they come from, but still, they look up to prestige varieties as a desired outcome, although they themselves are examples of the high level of difficulty of attaining that goal. On the one hand teachers accept that effective communication and intelligibility are the main goals when conversing in English, yet on the other, standard varieties are kept at the core of English teaching, dooming learners many times to the predetermined failure of not achieving the targeted native-like proficiency explicit in the EFL model.

In a similar fashion, Jenkins (2005) interviewed eighteen Non-Native-Teachers-of-English (NNTE's) about the way they perceived their own English in relation to the standard. She found that informants deemed Standard English as good, correct, proficient and competent. On the other hand, a non-native accent was mostly described as the opposite: not good, incorrect, strong and deficient. Mckay (2003) found similar results studying the attitudes of Chilean teachers towards EIL. In this sense, Jenkins (2007, p. 141) continues to elaborate and emphasizes the difficulty teachers have to '...disassociate notions of correctness from 'nativeness' and to assess intelligibility and acceptability from anything but a NS (Native Speaker) standpoint...' In this respect, the identities of teachers are crucial. Teachers, as individuals who have been engaged for years in the learning of a language, are somehow threatened by the fact that accomplishing the level of perfection they have long aimed at is no longer the only desirable goal. In the light of this reasoning, it is not surprising that language teachers seem reluctant to accept a model for English learning that overthrows linguistic 'perfection' as the center of language learning. What some teachers may fail to comprehend, however, is that the objectives for learning a language are diverse. This is what the EIL model brings to the table: the possibility of a more diverse and inclusive approach that provides learners with tools to cope with the communicative demands of the rapidly changing character of English in international settings.

EIL described: What it sounds and looks like

A good place to start to understand EIL is to define what it is not. A common misunderstanding (Jenkins, 2007, p. 19) of EIL is that it is a variety in itself. The EIL model is not intended to provide rules for a universal form of English that all non-native speakers should be taught and adjust to. Neither does it suggest that this 'universal' language is a prescriptive endeavor aimed at facilitating communication between multilingual speakers (Seidlhofer, 2006, p. 45). Another common misconception is that EIL is a model that is intended to replace EFL and eradicate it from the ELT scenario. In the contrary, the EIL aims at providing an alternative for those who use English in international settings with multilingual speakers rather than only with native ones (Seidlhofer, 2005).

So, what is EIL? Jenkins (2009, p. 143) defines it in a very simple way: 'Very roughly, it is English as it is used as a contact language among speakers from different first languages'. Jenkins accompanies her definition with five different assumptions that help us understand EIL more precisely and that are here presented:

The amount of research that has been developed so far to describe EIL, though significant, is not extensive. Jenkins (2006) and Seidholfer (2005) provide us with a brief overview of what has been accomplished so far. These efforts have concentrated mainly on the phonetic and phonological levels (Brown, Deterding and Lin, 2005; Kirkparick, 2004; 2007; Jenkins, 2000), the pragmatic level (House, 1999; Meierkord, 1996) as well as on particular domains of EIL use (Mauranen, 2003). In particular, EIL has seen a lot of development in the Asian countries, where scholars have been describing some of the features of English in this area of the world.

Evidence of this is Brown, Deterding, and Lin (2005). In this edited book, a very thorough description of Singaporean English is provided. It focuses mostly in segmental and suprasegmental aspects of this variety. Also, aspects of intercultural intelligibility and pragmatics are addressed. For example, Brown and Deterding (2005) explain that Singaporean English 'does not distinguish between pairs of vowels that are distinct phonemes in RP' (p.10). Short and long vowels merge, reducing the vocalic variety. There is no length contrast in this variety of English, therefore vowels like /I/ and /i:/, /L/ and /a:/ and / :/ and / / are pronounced the same.

Front vowels /e/ and /æ/ are equated and pronounced as /e/. Similar merging of sounds occurs with pairs of consonants. Nonetheless, description of Singaporean English has also been done at the grammatical level. Characteristic of Singaporean English are the omission of articles and the use of infinitive forms where gerunds are customary McArthur (2002), as cited by Kirkpatrick (2007) .

In a more general fashion, Kirkpatrick (2007) provides us with an overview of the linguistic features of English in Asia. Among other characteristics, Kirkpatrick demonstrates that, at the syntactic level, Asian speakers of English prioritize the use of the present simple over all other tenses. Also, the author describes the lack of subject verb agreement, the absence of third person marking and the use of non-traditional collocations as the most common features of Asian English as opposed to standard varieties. Likewise, at the phonetic and phonological levels, noticeable features include the merging of the consonants /q/ and /ð/ as well as /f/ and /p/. Finally, a clearly identifiable feature is the simplification of final consonant clusters. Examples include 'first' /f3:rst/ and expect /Ikspekt/ where the final consonant is omitted.

In a similar way, studies of the same kind have been conducted in Europe, but have concentrated on unveiling features that are common cross-culturally, rather than describing specific local varieties. One of the most influential descriptive endeavors in the EIL model is the Vienna-Oxford International Corpus of English (VOICE henceforth). Its main aim was to provide EIL data for the use of researchers all over the world. The corpus currently comprises one million words of spoken EIL mainly from European settings but not exclusively (VOICE, n.d).

Based on this corpus, Seidlhofer (2004) has focused her research on EIL lexicogrammar. In particular, she has described the linguistic features of EIL that are normally considered errors in traditional ELT. Among these, she has found: 1) unmarked third-person simple present, 2) interchangeability between who and which when used as relative pronouns, 3) article omission and intrusion, 4) lack of grammaticality in tag question use and the use of a universal isn't it? or no?, 5) verbal redundancy by means of intrusive prepositions as in study about, discuss about, 6) extensive use of semantically general verbs and avoidance of semantically determined ones; 7) uncountable noun pluralization, and 8) replacement of infinitive forms by that-clauses (I want that you). Additionally, she found that one of the main problems for intelligibility between speakers of English with different L1's derives from what she calls unilateral idiomaticity. Unilateral idiomaticity hinders communication because what is idiomatic to one speaker may not be for his/her interlocutor. The use of idioms, phrasal verbs and metaphorical figures unilaterally by a speaker may result in communication breakdowns given that the interlocutor may not familiar with the expression (Seidlhofer, 2011, p. 135).

S: I'm tired of studying. I want the semester to be over.

P: Tell me about it!

S: Well, I've been studying really hard and

feel a little sick. I really want to rest.

In the example, P's utterance is one that reflects that he/she is going through the same experience expressed by S. However, since S does not share the idiomaticity of the expression Tell me about it!, S fails to understand what M was expressing. Instead, S understands the utterance literally: as a request for further information and proceeds consequently.

The Phonological Core of EIL

One of the most influential works towards a linguistic description of EIL is that of Jenkins (2007), where she describes what she calls the phonological core of EIL. This phonological core is a set of features that are crucial for intelligibility when two speakers of different L1's communicate. For example, the pronunciation of the voiced flap /r/, characteristic of General American, is particularly problematic for non-native speakers of English who often approximate it to /d/ or /t/, depending on their knowledge, and the spelling and etymology of the word. Although this approximation would not pose problems to intelligibility between proficient speakers of English–native or not- who would resort to linguistic and/or extralinguistic context, non-proficient speakers would probably encounter difficulties sorting out meaning because they mainly resort to acoustic information (Jenkins, 2007, p. 140) For this reason /r/ is not included in the EIL phonological core. Instead, all instances where this phoneme is pronounced would be replaced by /t/ as in /leIt r/ or /d/ as in /læd r/ which are less likely to cause confusion.

In order to establish the EIL phonological core, Jenkins starts by revisiting the concepts of inter- speaker and intra-speaker variation. In relation to inter-speaker variation she argues that it is necessary to regard such variation as natural rather than as deviant. By this she means that variation in L2 should be as acceptable as it is in L1. Examples of this are very common to find in the ways L1 speakers react to variation in L1 and L2. L1 inter-speaker variation is more often than not regarded as legitimate on the basis of geographical origin. Also, it is important to remember that L1 variation, just like L2 inter-speaker variation, can hinder intelligibility. However, L2 inter- speaker variation is most often regarded as deviant from the L1.

She then proceeds to discuss some of the segmental and supra-segmental features that characterize this L2 variation and elaborates on the effect they have on intelligibility. Also, she points out that one of the main challenges of the researcher is to be able to determine whether cases of inter-speaker variation constitute evidence of a speaker's interlanguage or display a particular form of established variation. Once she does this, she explores some of the segmental and suprasegmental features and problematizes the general belief that segmental variation is less harmful to intelligibility than suprasegmental variation. Afterward sh e discusses seg men tal an d suprasegmental features in the light of inter and intra- speaker variation as well as interlanguage intelligibility, she sets out to present the phonological core of EIL. As was mentioned above, this is made up of those features that play a role in intelligibility according to her research. In her proposal, features at the segmental level such as all consonantal sounds (except for /q/ and / ð/) and dark 'l' [ ], the long-short contrast in vowel quality, consonant clusters at the beginning of words and the production of nuclear stress all make part of the phonological core of EIL. This is, speakers from all origins should learn how to produce these sounds within the core to favor intelligibility when interacting with speakers of English from different origins. Conversely, suprasegmental features like weak forms, stress-time rhythm, pitch movement and word stress do not impede intelligibility between EIL speakers and should not excessively occupy targeted language learning goals. She finishes her book by discussing some of the pedagogical implications of adopting her proposal, but these will be discussed in the following section.

The implementation of an EIL model implies a number of changes in the conception, design, delivery and assessment of English teaching programs. An EIL perspective in ELT comprises an essential change in the very core of what is taught and an overthrow of standard language ideologies as the foundation of language learning.

In this sense, a number of authors have approached this matter from different perspectives. Matusda and Friedrich (2010) make a proposal for the design of an EIL curriculum. The authors discuss a number of elements that should be taken into account when designing curricula for EIL courses. These elements are: choosing an instructional model, making sure students are exposed to different varieties of Englishes and their users, giving strategic competence a central role in the teaching of English, using instructional materials that display these variations and increasing awareness of World Englishes.

This contribution is of great importance especially for teachers and curriculum designers who many times find themselves caught in the middle of theoretical discussions and are told to implement critical approaches but do not find sound advice on how to do so. This is of particular relevance in the case EIL since it is very hard to deny that English, as it is used by NNSE's, entails peculiarities that need to be taught and learned, it has become clear that these need to be described. Additionally, since it is not a particular variety that can be isolated, it is hard to determine the linguistic contents of such course. Instead, it is a function that fluctuates and varies from conversation to conversation, from speaker to speaker. There is however one substantial concern with their proposal. In regards to the variety of English to be taught there seems to be a conceptual contradiction. Even though they acknowledge the fact that adopting an EIL model is a way to integrate local linguistic practices and to give them a place in the emergence of local varieties of English, they still propose that the variety of English to be taught should be one that has already been established. This entails at least one methodological hindrance. Established varieties are those from the 'inner' or some 'outer' circle countries. However, experience tells us that teaching materials from 'outer circle' countries are hardly found, but more importantly, these varieties are sometimes not even heard of in expanding circle countries and it is easy to predict that they can encounter a lot of resistance on the part of English learners due to their lack of 'prestige'. Therefore, the only option teachers are left with is to perpetuate the teaching of standard varieties. This is a major, though understandable issue since EIL still seems to be at a very initial stage. The reason for this is simply that engagement in the description of both of these approaches is just setting off.

A similar contribution is that made by Jenkins (2000). She discusses the need for English teachers to incorporate the negotiation of intelligibility in the classroom through the use of communicative strategies, the necessity to develop students' ability to accommodate to distinct situations and speakers and a sense of cooperation in communication. Also, she elaborates on the implications of her proposal for the teaching of English pronunciation. She asserts that since interacting with native varieties is no longer the rule for NNSE's, it is not necessary to educate teachers on how to help students achieve these native standards. Her point is not merely an ideological but also practical one. For her, people should not conform to standard varieties simply because they would be learning something that will not equip them with the necessary tools to successfully engage in intercultural communication.

For this reconceptualization of pronunciation instruction Jenkins (2000, p. 195) suggests elements such as the sociolinguistics of phonology, awareness- raising notions of the relativity of the notion of the standard, dialect, inter-speaker and intra-speaker variation and the need for accommodation of speech depending on interlocutors and contextual circumstances. Although this seems to be a very thoughtful proposal, a few questions remained unanswered. First, it is hard to imagine that teaching the phonological core of EIL is something that can be done without first acknowledging and describing what local varieties look like.

In other words, it is clear that Jenkins' proposal of the core is based on extensive research and that the question of intelligibility is crucial for EIL but, although she asserts that there is room for local variation within the EIL model, very little is said on how this can actually take place. While there is not sufficient empirical work on the description of EIL, there is even less in the description of local Englishes, particularly in 'expanding circle' countries. That is, since EIL is a model that allegedly provides room for variation, one wonders if this phonological core does not fall into the trap of prescriptivism by putting local Englishes in a disadvantaged position vis-à-vis the phonological core of EIL. Even though Jenkins addresses this criticism throughout her book, one is still left with the question whether changing the variety to be taught is only a change in the standards.

Another work that addresses pedagogical but also political matters is that of Sifakis (2007). This author concentrates his efforts in a teacher education scheme that follows a transformational learning model. He calls for a new paradigm in English teaching by helping teachers become better acquainted with the ways standard language ideologies function as a way to develop in them a more critical educational attitude for language learning and empower students to become agents of social transformation. His work uses elements of widely-known authors on critical pedagogies such as Pennycook, Cannagarajah, Phillipson and Mckay.

In an equally politically-oriented effort, Hu Xiao (2004) advocates for the adoption of China English as a legitimate variety and that, as such, it should at the center of English teaching in China. For him, it is obvious that teachers of English need to integrate the culture of China and that this variety should be described and systematized. Also, the author asserts that the nativization of English is China is inevitable and that therefore English textbooks and materials that originate in the US and Britain should no longer be used. Instead, it is proposed that such material should portray the local culture.

On the other hand, EIL has, predictably, encuntered a lot of resistance, as was mentioned before. Paul Bruthiaux (2010) questions the figures posed by authors like Graddol on the number of English speakers in the world. While Bruthiaux recognizes that the 500 million estimates of native speakers may be accurate, he problematizes the nature of the contexts of 'outer circle' countries. The author states that in postcolonial territories, where local varieties have emerged and been established only a very limited amount of the population (up to 20%) is proficient in that variety and use it on a regular basis. The remaining 80% percent, the author argues, is immersed in contexts where English is neither used nor required and students have very low levels of proficiency, if any at all. Through this reasoning he concludes that the EFL model is more accurate to describe these populations. The author continues to question the claim that room should be provided for local varieties to emerge. He disregards this possibility since he asserts that for this to happen it is necessary that English be largely used in these communities, which, for him, is not the case.

Bruthiaux also debates the validity of adopting EIL since it is so variable and blurry, but more importantly, because, given the constraints and challenges of the educational context in these EFL/ESL settings such as limited class time, almost no exposure to the target language and ill-trained teachers, it is mandatory to adopt a model that is more stable and that facilitates learning. Clearly, the questions brought up by the author are worth examining, particularly when he refers to the constraints and the sometimes idealized image of the linguistic landscape of 'outer circle' countries that we get from progressivist approaches in language teaching. However, one is left wondering if such a non-critical approach to these matters ignores the imperialistic character of Standard English ideologies and fears that this can easily be seen as vulgar pragmatism.

Finally, Seidlhofer (2011) proposes two major changes that are related to the teaching of EIL. First, were this approach to be adopted, the focus should shiftfrom learning a language to learning to language (p. 198). What this means is that strategic competence should have a more essential role than it traditional has. Negotiating communication, accommodating linguistically to interlocutors, portraying linguistic solidarity and the exploitation of non-linguistics resources are central for EIL communication and this should be reflected in the curriculum. Consequently, there should be changes in the education of English teachers (p. 201). With such a transformation of the teaching, teachers should be trained into privileging process over form, i.e. the processes through which speakers communicate and transact meaning should be more important than the forms of the language students learn. Also, teachers should be educated into developing language awareness among their pupils. Knowledge about the language in this model is as important as knowledge of the language. In this approach, learners of English gain much more agency since, although they can be taught strategic competence and knowledge of the language, self-discovery of communicative strategies is very much their responsibility, just like in any real linguistic exchange. This way, learners can find out for themselves what works best for them with any particular interlocutor or group of interlocutors. Developing class activities where this self-discovery process is practiced can help students realize what is required of them to succeed communicatively in real settings.

Conclusion

In this review of the literature I have presented an array of contrasting positions towards the EIL model. I have navigated through the implications of EIL in the ownership of English as an international language and the concept of native-speakerism in language teaching and learning. I have reviewed some research studies that address the issue of identity and attitudes towards EIL on the part of learners of English and the contrasting views between the actual language varieties of non-native speakers and the perceptions of English teachers and speakers on the language that should be learned and taught. By doing this, I expect to have provided an overall picture of some of the dominant debates and trends in EIL which I expect will help initiate a discussion of the issue of EIL as an alternative to be discussed in Colombia. In times when critical pedagogies are gaining momentum in academic circles, it seems predictable that this debate will gain relevance in Colombia in the near future. This debate should lead us to consider whether EIL is applicable in the Colombian context and what the implications of this would be. It also may lead us to question whether there are specificities to the variety of English spoken by Colombian that can be legitimized and not considered as deviant or problematic in English learning.

References

Brown, A. & Deterding, D. (2005). A Checklist of Singapore English Pronunciation features., in: Deterding, D., Brown, A & Low. E. (eds) (2005) English in Singapore: Phonetic Research in a Corpus, Singapore: McGraw Hill, pp.7 - 14. [ Links ]

Bruthiaux, P. (2010). World Englishes and the Classroom: An EFL Perspective. TESOL Quaterly. 44, 365-379. [ Links ]

Crystal, D. (2004). The Language Revolution. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Coskun, A. (2011). Future English Teachers' Attitudes towards EIL Pronunciation. The Journal of English as an International Language. 6, 47-68. [ Links ]

González, A. (2007) Professional Development of EFL Teachers in Colombia: Between Colonial and Local Practices. Ikala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura 12,309-332. [ Links ]

Graddol, D. 2006. English Next: Why Global English May Mean the End of 'English as a Foreign Language'. London: British Council. [ Links ]

Holliday, A. (2005) The Struggle To Teach English As An International Language. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. Oxford Applied Linguistics. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J.(2000) The Phonology of English as an International Language. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. Oxford Applied Linguistics. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J. (2005). Implementing an international approach to English pronunciation: The role of teacher attitudes and identity. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 535-543. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J. (2006). Current Perspectives on Teaching World Englishes and English as a International Language. TESOL Quaterly, 40, 157-181. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J. (2007) English as an International Language: Attitude and Identity. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. Oxford Applied Linguistics. [ Links ]

Jenkins, J. (2009). World Englishes: A Resource Book for Students (2nd edn.) London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kachru, B. (1985). Standards, codification and socio- linguistic realism: the English language in the outer circle' in R. Quirk and H.G. Widowson (eds): English in the World: Teaching and Learning the Languages and Literatures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 11-30. [ Links ]

Kirkpatrick, A. (2010). The Routledge Handbook of World Englishes. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kirkpatrick, A. (2007). World Englishes. Implications for International Communication and English Language Teaching. Cambridge; New York; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Macías, D. (2010). Considering New Perspectives in ELT in Colombia. HOW, 17. 110-125. [ Links ]

Matsuda, A., Friedrich, P. (2010). English as an International Language: A Curriculum Blueprint. World Englishes, 30, 332-344. [ Links ]

McKay, S. (2003). Teaching English as an International Language: The Chilean context'. ELT Journal, 57(2), 139-148. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia. (2006) Estándares Básicos de Competencia en Lengua Extranjera: Inglés. Bogotá. Imprenta Nacional. [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. (1994) The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language. London; New York: Longman. Language in Social Life. [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. (2007) The Myth of English as an International Language. In Makoni, S.,Pennycook, A. (Eds.), Disinventing and reconstituting languages (pp. 90-115). Buffalo: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Qiong, H. (2004). Why China English Should Stand Alongside British, American, and the Other 'World Englishes'. English Today: The International Review Of The English Language, 20, 26-33. [ Links ]

Sari, D., & Yusuf, Y. (2009). The Role of Attitudes and Identity from Nonnative Speakers of English towards English Accents. Journal Of English As An Interna- tional Language, 4 110-128. [ Links ]

Seidlhofer, B. (2004). Research Perspectives on Teaching English as a Lingua Franca'.Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. 24. 209-239 [ Links ]

Seidlhofer, B. (2005). Key Concepts in ELT: English as an International Language. ELT Journal. 59. 339-341. [ Links ]

Seidlhofer, B. (2006). English as an International Language in the Expanding Circle: What it isn't in R. Rubdy and M. Saraceni (eds.). English in the World: Global Rules, Global Roles. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Seidlhofer, B. (2011). Understanding English as an International Language. Oxford. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sharifian, F. & Kirkpatrick, A. (2011). English as an International Language: An Overview of the Paradigm. Retrieved on November 20, 2012 from: http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/eil/lecture-2011.php [ Links ]

Sifakis, N. (2007). The education of teachers of English as an International Language: a transformative Perspective. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17, 355-375. [ Links ]

Viswanathan, G. (1989). Masks of Conquest: Literary Studies and British Rule in India. New York: Columbia UP. VOICE. Vienna Oxford International Corpus of English. Retrieved on November 25,from: http://www.univie.ac.at/voice/page/team_members#researchers [ Links ]

Widdowson, H.G. (1998). The Ownership of English in V. Zamel and R. Spack (eds.): Negotiating Academic Literacies. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum: 237-248. [ Links ]