Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

versión impresa ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. vol.16 no.1 Bogotá ene./jun. 2014

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.1.a04

http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2014.1.a04

Anglicism: An active word-formation mechanism in Spanish1

Anglicismos: un mecanismo activo de formación de palabras en español

Constanza Gerding, Ph.D.

Universidad de Concepción, Chile

Concepción, Chile

cgerding@udec.cl

Mary Fuentes, M.A.

Universidad de Concepción, Chile

Concepción, Chile

marfuent@udec.cl

Lilian Gómez, Ph.D.

Universidad de Concepción, Chile

Concepción, Chile

ligomez@udec.cl

Gabriela Kotz, Ph.D.

Universidad de Concepción, Chile

Concepción, Chile

gkotz@udec.cl

Received: 16-Oct-2013/ Accepted: 11-Mar-2014

To cite this article

Gerding, C., Fuentes, M., Gómez, L. & Kotz, G. (2014). Anglicisms: An active word-formation mechanism in Spanish. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 16(1). 40-54.

Abstract

The adoption of the American neoliberal paradigm has resulted in significant social changes worldwide. Its effects are evident in different fields including language use. Thus, the influence of the English language and American culture on other languages is of interest tolinguists, translators, and SL teachers. This study aimed at identifying the presence of Anglicisms in the press in order to describe them, determine their frequency and patterns of use, and infer the causes of their incorporation in Spanish as well as its implications for SL teaching. Anglicisms were collected by the Antena Chilena de Neología between 2006 and 2012 and then analyzed according to formal characteristics and contextual domains. Results showed that Anglicisms have a strong presence in today's press in economics, computer science, sports, and culture, and that speakers adopt rather than adapt them. Four factors may explain the introduction of Anglicisms to Spanish: lexical gaps, social prestige, linguistic economy, and user preference. It was concluded that the English language and American culture have a significant presence in the press through Anglicisms, which needs to be taken into account in ESL teaching and translator training.

Key Words: Anglicism, ESL, neologism, spanish, translation.

Resumen

La adopción del modelo económico estadounidense de libre mercado ha producido cambios sociales significativos en todo el mundo y sus efectos son evidentesen muchas áreas del saber, incluido el uso de la lengua. La influenciadel inglés y la cultura estadounidenseresulta interesante para lingüistas, traductores y profesores de inglés como segunda lengua. Los objetivos de este estudiofueron: identificar la presenciade anglicismos en la prensa, describirlos, determinar su frecuencia y patrones de uso, inferircausas de su incorporación al español y determinar implicancias en el aprendizaje del inglés. La Antena Chilena de Neología recopiló anglicismos entre 2006 y 2012 y estos luego se analizaron según sus rasgos formalesy áreas del conocimiento donde ocurrían. Los resultados indican que los anglicismos tienen marcada presencia en la prensa actual en economía, computación, deporte y cultura,y que los hablantes adoptanmás que adaptan estos préstamos. Cuatro razones pueden explicar la incorporación de anglicismos al español: vacíos léxicos, prestigio social, economía lingüística y estilo. Se concluyó que el inglés y la cultura estadounidense tienen mucha importancia en la prensa por la frecuencia de anglicismos, hecho que debe considerarse en el aprendizaje del inglés como segunda lengua y en la formación de traductores.

Palabras clave: anglicismo, español, inglés como L2, neologismo, traducción.

Introduction

The Antena Chilena de Neología2, one of the six branches of Antenas Neológicas3,has been conductingresearch on lexical neology since 2003, in collaboration with several other institutionsfrom Latin America and Spain. Itsmain objective is to detect, collect, and analyze neologisms of different varieties of Spanish found in thewritten press, and to discuss implications for practice. The ultimate goal is twofold: 1) to study the vitality of Spanish and thus con-tribute to updating mainstream dictionaries, and 2) to shed light on pedagogical praxis.

According to Ortega (2001),journalistic language is an inexhaustible source of lexical creativityand the press is probably the most effective vehicleof Spanish lexicalrenewal. Bearing this in mind, studying lexical neology in the press isan evident need, especially because newspaper publications naturally portray culture, society, and people's idiosyncrasy, all of which have an effect on education.

As the coinage of new wordsis somewhat slow compared to the facts that need to bedescribed,lexical gaps requiring the import of foreign words tend to be a common occurrence. Thus, the influence of one society on anothermay manifest itselfinwords borrowedfrom predominant cultures.An example of this isthe influence of globalized English and American culture on Chilean society. This has triggered the introduction of Anglicismsinto Spanish.

The term globalization, which involves social, political, cultural, and economic aspects, came into fashion atthe turn of the 20th century. In Chile, it becametangiblewith the adoption of thesocial market economy paradigm in the early 1980s. In this context, Chile has become one of the most open economies in the world (Mazzo, 2008) and an active member of internationalorganizations.The above would explain a significant number of Anglicisms in Chilean Spanish.

Today, communication requires considerable knowledge ofother languages, cultures, and lifestyles (Rodríguez, n.d.). In this scenario, English iskey - it is the mother tongue of millionsand the second language of millions of others worldwide. This is greatly due to the hegemony of the United States as a cultural, military, political, scientific,and economic world power, and leads to what Ritzer (2002) calls the "Americanization" of society. Thus, English,together with Spanish and Mandarin, has gradually becomeanactual lingua franca (Universia, n.d.), with obvious opportunities for SL teachers and students because of the import oflexical and syntactic constructions from English.

In fact, loanwords occur in every language as a consequence of language contact. Hence, borrowing lexical items is a frequent mechanism for languages to increase their lexicon and to expand the horizons of their reality (Delgado, 2005). Spanish has systematically introduced a number of Anglicismsvia the press. Different studies in the field of neology conducted in Chile (Diéguez, 2004; Fuentes, Gerding, Pecchi, Kotz, & Cañete, 2009; Sáez, 2005) confirm this tendency, whichmay indicateawillingnessof speakers to assimilatethese loanwords.

The press is,to a great extent, responsible for the dissemination of neologisms. According to Ortega (2001), the type of language used in the media is a source of high lexical productivity in different areas. In fact, various language changes are manifestin the press: revitalization of words in disuse, formation of compound words, and use of foreign expressions.Perdiguero (2003) refers to the press as a 'unique observatory'for the compilation and dissemination of neologisms, hypothesizing that the power of the media could bridge the communicative problems caused by lexical innovations.

Sáiz (2001) suggests that English lexical items are readily incorporated into Spanish in the Chilean press, mainly in economics.However, in the last decade the number of Anglicisms has also increased in other fieldssuch as technology, fashion, and advertising. According to Sáez (2005), this steady process has generally taken place in fields requiring specialized vocabulary, such as economics, trade, science, technology, tourism, music, fashion, show business, sports, and communications. A study on Anglicisms in the Costa Rican press concluded that there is a proliferation of these loanwords in retail, technology, and show business, mainly due to the adoption of the free market paradigm in Costa Rica (Delgado, 2005). Alfaro (1984) sustains that Anglicisms have penetrated Spanish by different means, either impetuously or subtly, but always effectively through news agencies such as the press, film, travel, business, science, sports, and international and social relationships.

The role of the press should not be underestimated as it contributes to the gradual shift of foreign words from specialized language to everyday use. In fact, it is widely known that journalists use Anglicismsforstyle, prestige, slackness, linguistic economy, language specificity (determinologized jargon), and to fill lexical gaps, among other reasons.The influence of the press in the dissemination of neologisms has led to an accelerated renewal process and an in-crease of the Spanish lexicon (Sáez, 2005). This fact may be taken advantage of in the SL classroom as these Anglicisms may act as a bridge for students to expand their knowledge of English and even access more specialized vocabulary in the SL.

Readers sometimes attribute so much value to foreign words spread by the press that theyincorporate them into their own linguistic repertoire. A study conducted in Chile (Diéguez, 2004) suggests that experts sometimes encourage the use of neologismsinthe mass media. However, it is thejournalists and editors who ultimatelydecide to adopt or adapt new words, Anglicisms in particular. The use of these loanwords in Spanish has also been observed in non-specialized informative texts all over the Americas, including countries that are not so fond of American culture (Haensch, 2005). It could be argued that the hegemonic power of English is very influential:the dominance of English as globalizationoccurs at the level of international mass communication, which involves issues such as the Americanization of global culture.

Loanwordshave different names depending on the linguistic approach used to analyze them. From the language contact perspective, Fontana and Vallduví (1990) refer to them as 'code switching,' whereas from a prescriptive viewpoint,they are considered'errors' (Domínguez, 2001). However, from a translationalor lexical standpoint, the borrowing process is called'loan translation'or calque (García, 1989). From a linguistic viewpoint, some of the names given to this phenomenon include loanword, alien word, alienism, foreign word, foreignism, andborrowing (Zhou & Yajun, 2004). Linguists, lexicographers, neologists, translators, and language teachers sometimes use these words interchangeably and sometimes with slightly different meanings.

Nevertheless, there is no consensus on a single term to name borrowed words. For example, some authors makeadistinction between 'loanword' and 'foreign word,' the former used as a term for naturalized foreign items, i.e. those that areadapted to the phonologicaland morphological systemsof the target language, and the latterfor non-naturalized items, i.e.thosethat are adoptedin an unmodified form (Abraham, 1981; Cardona, 1991; Fuentes, Gerding, Pecchi, Kotz, & Cañete, 2009; García, 1989; Lázaro, 1983). In fact, loanwordsmay show different degrees of adaptation to the target language: from a zero-assimilation degree (non-adapted loanwords),to almost full assimilation, for ifadaptation were complete, the item would no longer be a loanword (Márquez, 2006).

In lieu of this diversity, the term 'loanword'in this study will be used to refer to 'a word or expression taken by any given language from another,' which may be 'adopted' or 'adapted'.The Antena Chilena de Neologíaproject defines 'adopted loanword' as one that remains intact when incorporated into the target language. On the other hand, an 'adapted loanword' is one that has undergone phonological or morphological changes to conform to the target language rules. The phonological level is not included in this definition because the project focuses on the written form of foreign lexical items in the press. Apart from being formal neologisms, Anglicisms constitute a sociolinguistic phenomenon from the viewpoint of their structure and social reach, with strong influence bothon specialized and everyday language (Márquez, 2006).Not only is this of interest to linguists, journalists, and translators, but also to both ESP and ESL classrooms.

As for the reasons for whichonelanguage adopts or adapts words from another, Guerrero (1997) posits that loanwords usually come from a language spoken in a country witheconomic and scientific influence on the receiving culture,or inone with high prestige in the field in which the loanword is used. What is more, when using a loanword, the speakeris trying to reproduce the models associated withthe foreign language from which itcomes (Delgado, 2005).Therefore, learning a second language implies being aware of the culture and the realities portrayed in that language, which does not equate to cultural assimilation.

This articlepresents the results of a descriptive study onthe proliferation of Anglicisms in Chile based on data collected from newspapers.The principalaim was to determine the proportion of neological Anglicismsin the press to other newly coinedwords. The specific objectives wereto identifyand describe Anglicisms, to verify type and token frequency, to inferpossible reasons fortheir incorporation into Chilean Spanish, to gauge readers' neological feeling, and to conjecture about implications for translation and SL teaching.

Previous studies (Fuentes et al ., 2009; Fuentes, Gerding, Pecchi, Kotz,& Cañete, 2010a; 2010b) reveal thatloanwords account for approximately 30% of neologisms found in the Chilean press, considering all types of neological formations. From that percentage, approximately 80% corresponded to Anglicisms. Given the way in which these loanwords are used in Chilean newspapers, it is evident that most are adopted.

What is the current influence, then, of English on the Chilean variety of Spanish,taking globalized economy and trade and international relations into account? Why wouldlanguage users accept this influence as a form of acculturation? How does this phenomenon affect writing style, translation, and SL teaching? These concerns drivethe analysis of Anglicisms in the present study.

Methodology

The corpus used in this study consistedof Anglicisms collected from the press by the Antena Chilena de Neología for a period of seven years (20062012). This procedure was done both manually and semi-automatically4 and data was stored in the database of the Observatori de Neología (OBNEO, 2003). The sources were twonewspapers:El Mercurio and El Surof national and local circulation, respectively. The organization intosections bywhich the information is presented in these newspapers served as the basis for the construction of domain categories used in data analysis.

The selection criterion to determine the Anglicized status of each unitwas lexicographic and psychological (Adelstein & Badaracco, 2004; OB-NEO, 2003).According to the classification protocol used (OBNEO, 2003), all neological units must be retrieved only once per newspaper issue. Therefore, the token frequency of Anglicisms is likely to be higher than the results show, which may affect the ecological validity of data in this study.

The reference corpora used to verify the neological standing of each candidateincludedthe Diccionario de la lengua española (Battaner, 2001), the Diccionario de la lengua española (2001, and the online version),and the Diccionario de Uso del Español de América y España (Battaner, 2002). Thus, units such as'airbag,''e-mail,''hardcore,''hardware,'' mailing,' and 'software,'which had already been entered in at least one of the above dictionaries, were discardedas neologisms.

From the corpus, a sample of units was selected by the researchers to test the 'neological feeling' (Sablayrolles, 2000) on readers. This concept refers to the use of native speaker intuition to spot easily recognizable neologisms. With this in mind, a list including 173 very familiar Anglicisms typically found in newspapers was emailed to 33 informants for them to classify their degree of familiarity on a scale of five points, five being 'most familiar.'An accidental sampling method was used to select the informants: equal number of men and women, 25 years of age or older, and Chilean residents with technical or professional degrees unrelated to English were selectedto avoid linguistic bias.

Results

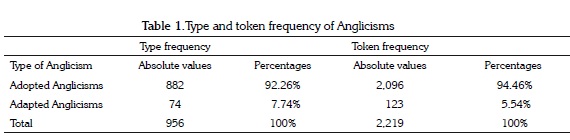

A total of 10,642 neologisms corresponding to different types of word formation (affixation, word-composition, loanwords, etc.) were collected and analyzed in the seven-year period mentioned above. Of this total, 2,973 units (27.93%)corresponded to both adopted and adapted loanwords from different languages, 754 of which were new lexical units from languages other than English. The rest of the loan itemscorresponded to 2,219 English loanwords or Anglicisms. Thus,N = 2,219 token Anglicisms, of which 2,096 were adopted tokens (with a type frequency of 882 units) and 123 were adaptedtokens (with a type frequency of 74 units), as shown in Table 1.

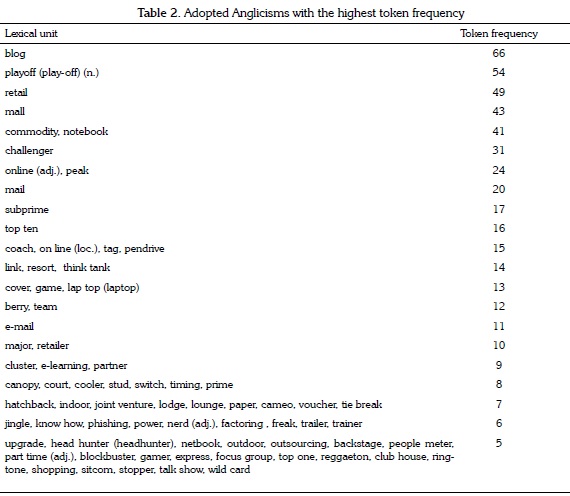

The very high percentage of adopted Anglicisms may show a certain degree of Americanization of Chilean society, as most English loanwords belong to business and trade, ICTs, and leisure, three domains in whichthere is a clear influence of Americanculture in Chile (Gerding, Fuentes,& Kotz, 2012) due to the adoption of the Chicago neoliberal development model, among other factors. By way of illustration, the most frequently adopted Anglicisms were 'blog' (66 tokens), 'retail' (49), 'mall' (43), 'commodity' (41), and 'notebook' (41). The word 'blog' has only recently been entered into one of the dictionaries (Real Academia Española, 2013) used as contrastive lexical corpora for this study.

Of the 123 adapted Anglicisms, a very small proportion (< 8% type frequency and < 6% token frequency) evidenced some kind of adaptation (see Table 1). This may indicate that Chilean speakers tend not to naturalize English words, which is an advantage to ESL and ESP praxis.

Most adapted Anglicisms appeared only once in the corpus: básquetbol(basketball), esmog (smog), broder(brother), flíper(flipper),andpenalty (penalty). However, a few adapted units had a higher token frequency: ránking (ranking, 16), pendrive (pen drive, 15), reggaetón (reggaeton, 5), biodiésel (biodiesel, 4), and esnórquel (snorkel, 4). It is interesting to note that the word pendriveis massively used in Chilean Spanish to refer to 'USB drive,' 'USB flash drive,' 'flash drive,' 'flash disk,' 'memory stick,' or 'data traveler,' which are usedin English, but the Anglicized forms'pen drive'or 'pendrive' do not appear in regular English dictionaries (Cambridge Dictionary, 2013; The Free Dictionary, 2013; Merrriam Webster's Dictionary, 2013; WordReference, 2013), although internet definitions can be found for this portable datastorage device.

Table 2 includes only adopted Anglicisms with a frequency of five or more tokens.Most of these units belonged to three main domains: ICTs, business, and leisure. These words seemed to be preferred by Chilean speakers due to their linguistic economy and trendiness.

All languages reflect a certain worldview, which is evident in the way words are formed. For instance, English pragmatism can be observed in such words as notebook/laptop (computador portátil), think tank (grupo de expertos en un laboratorio de ideas), e-mail (mensaje de correo electrónico), sitcom (comedia de equivocaciones para televisión). Not only are these words linguistically economical, but also globally transparent. Spanish, on the other hand, is more analytical than synthetic in nature (Orellana, 1987), and therefore more elaborate and explicit in terms of word formation. This is of utmost importance for translators as they may subscribe to either a normative or a functional approach. As a result, they may need to create an equivalent in the target language or incorporate an existing word from the source language by adopting or adapting it. As for ESL and ESP, it would be advisable to make this word formation dichotomy explicit to learners. Upon contrasting both processes, students should be given opportunities to formulate hypotheses about and experiment with contextualized word formation in English by means of open cloze items.

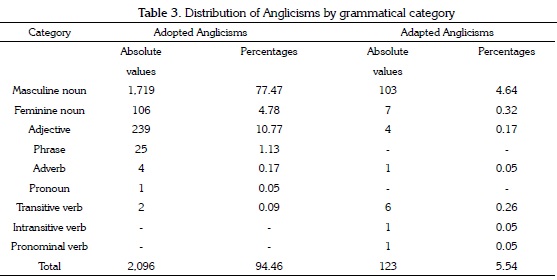

Table 3 presents Anglicisms by grammatical category. Nouns (e.g. challenger, mail, coach, tag, link, resort) were found to be themost productive of all neological units.This is also a constant in terminology Fuentes et al., 2009. Adjectives (e.g. online, nerd, part time), in turn, were second in use, although with a much lower token frequency. The occurrence of the othergrammatical categories was almostinconsequential.

Masculine gender nouns were by far the most recurrent, probably for two reasons: on the one hand, the OBNEO protocol establishes thatnouns whose gender is not explicitly marked in the text are to be considered masculine; on the other, Chilean Spanish speakers usually attribute masculine gender to Anglicisms,e.g. el backstage (las bambalinas), el club house (la casa club), los commodities (las materias primas), el sitcom (la comedia deequivocaciones para TV), el trailer (la sinopsis).The aforementioned attribution is the default mechanism to assign gender in Spanish. In fact, while feminine genderis restrictive in Spanish, masculine gender is used to refer to a) masculine nouns only (el camarón, el libro, los poderes), b) a group composed of males and females (la niña + el niño = los niños), and c) when gender in not marked in the noun (el o la periodista, el o la estudiante). In addition, the masculine gender is used generically to pluralize these unmarked nouns (los periodistas, los estudiantes). Gender is also a contrastive feature when it comes to English and Spanish analysis. In fact, ESL students would profit from opportunities to examine and reflect upon samples of SL input where gender may be an issue, and apply knowledge of the aforementioned contrast.

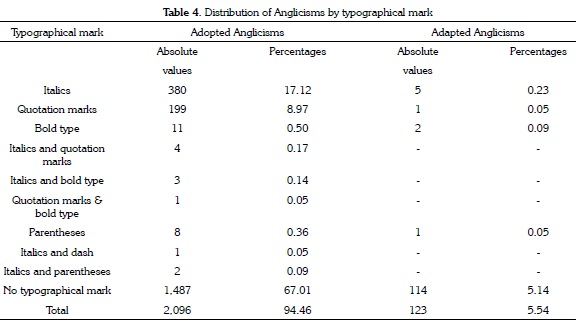

Words may have typographical markswhen it is deemed necessary to highlight them or when used either in their conceptual value or as a definition of another word (Diccionario de la lengua española, 2001). The writing conventions of the European Union (2011) require the use of italics to show the status of foreign wordsthat have not officially been recognized in Spanish. In this study, less than 30% of Anglicisms hadsome kind of typographical marks indicatingforeign origin (see Table 4). The fact that Anglicisms are typographically marked in Spanish may help ESL students to focus on form so as to have them readily available for both text processing and production.

The most frequent typographicalmarks were firstitalics, followed by quotation marks. While the Real Academia Española (2001) recommends both mechanisms to cite foreign words, most style guides advocate for the former. The word 'retail,'for example, appeared 49 times in the corpus, but was typographically marked(in italics) only three times. Previous studies based on Chilean press also reported infrequent use of typographical marks for Anglicisms (Diéguez, 2004; Fuentes et al., 2010b). This tendency could indicate a predisposition by Chilean Spanish speakers not to naturalizewords coming from English. However, the inconsistency in the use of these marks for citing foreign words may suggest a gradual, asystematic assimilation of loanwords in Chilean Spanish. This tendency to keep Anglicisms in the target language (Spanish) makes it easier for learners to understand and use lexical items in English texts.

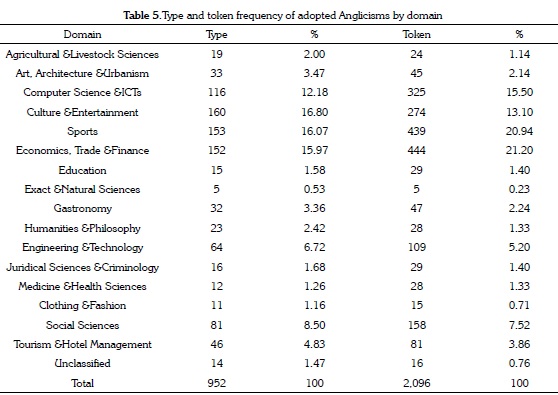

With respect to the contextual domainsin which neological loanwords are commonplace, this study determined that adopted Anglicismsshowed a much higher frequency (> 60%) in four domains, namely: a) computer science and ICTs b) culture and entertainment c) sports, and d) economics, trade, and finance (see Table 5). Lexical items from all these domains are highly meaningful to ESL and ESP high school and college students due to their motivational potential.

The highest type frequency of adopted Anglicisms corresponded to 'Culture andEntertainment.' In fact, a number of culture and entertainment expressionscoming from the Anglo-Saxon world, particularly those related to mass consumption (movie billboards, music stores,and pop music concert advertisements) have popular acceptance in Chile, especially among youth. The press probably introduces these unmodified Anglicisms for three main reasons:a) as a linkagebetween the source and the target culture, so as to produce some sortof empathy between the readers and the alluded cultural fact, b) to fill lexical gaps in Spanish, used instead of taking the time to explain the new meaning or even coin a new lexical unit in the target language, and c) for snobbery, due to the attempt of some people to gain a higher social status in a strongly stratified societysuch as that of Chile.Additionally, the press frequently introduces Anglicisms as terms (specialized jargon) that later determinologize and become easily accepted by Spanish speakers.

'Sports' and 'Economics, Trade,& Finance' exhibited the second highest type frequency and the highest token frequency of adopted Anglicisms.As for sports, Chileansoftenuse Anglicized jargon, probably becausethis kind of language is directly transferred from English by reporters and journalists. Speakers, in turn,incorporatesome of these loanwords when facing lexical voids or for linguistic economy. Castañón (2009) also identifies an abundant number of Anglicisms in sports, and he positsthat there is a strong assimilation of these loanwords in the Spanish sports press. As far as 'Economics, Trade,& Finance' is concerned, the strong influence of English may be associatedwiththe social and economic model based on the University of Chicago free market economy implemented in Chile in the 1980s (Samsing, 2008). Interestingly, many Chilean economists have been awarded post-graduate degreesby American universities; as experts, they contribute to the increase of Anglicisms available in the press. In addition, English is used as a lingua francaforcommunication with countries such as China, India, and Japan, with which Chile has signed trade agreements. Therefore, the use of adopted Anglicisms in the financial press is not surprising.

The third highest type frequency correspondedto 'Computer Science &ICTs.'Most softwareis available only in English on the Chilean market; for thisreason,Spanish computer jargon is plagued with Anglicized terms. Likewise, contentis muchmore abundant in English than in Spanish on the internet. The fast development of computer science and ICTs results in the urgency to filllexical gaps. This needis met by adopting (and also adapting) Anglicisms rather than translating terms. Coining lexical units by means of word-formationmechanisms typical of the Spanish language, although ideal for some, is not necessarily the main resource for naming new realities.

The number of Anglicisms found in the press may or may not correlate with thedensity in specialized texts. It may, in fact, be more closely associated to the amount and type of information newspaper editors decide to publish regarding a certain field at a given time. Ultimately, the useofadopted (i.e. unmodified) Anglicismsmay indicatethat Chilean journalists and speakersattribute social prestige to such words; therefore, journalists may use them to satisfy some readers' eagerness to belong to a higher social status.

Thetype frequency of Anglicisms was low in areas such as gastronomy, clothing and fashion, and tourismand hotel management. This does not mean that Anglicized language is infrequent in these areas in Spanish, but rather it may bemore likely to appear in other kinds of publications, such as specialized magazines, restaurant menus, store catalogs, advertisements, tourist brochures, and so forth.

All of these domains may be fertile ground for scaffolding as they may provide a starting point for learners who lack effective learning strategies or who possess a low SL competence.

The analysis ofthe highest type and token frequencies ofadopted Anglicisms in the corpussupports previous observations (Alfaro, 1984; Delgado, 2005; Diéguez, 2004;Haensch, 2005; Márquez, 2006; Fuentes et al., 2010b; Gerding et al., 2012;) with respect to the reasons for using them:

Linguistic economy, i.e. the use of shorter words in order to save time and get throughtext efficiently: mall (centro comercial), mail (mensaje de correo electrónico), notebook (computador portátil), playoff (partidos clasificatorios), retail (comercio aldetalle), upgrade (actualización de tecnologías de la información), sitcom (comedia deequivocaciones), stud (semental).

Style, fashion,oruserpreference, i.e. the choice of in-words to show interest in a special trend and, at the same time, sound fashionable: peak (hora punta), berry (baya), backstage(bambalinas), talk show (programa de tertulia).

A sign of social prestige, i.e. the inspiration ofrespect or admiration in a social group in order to be accepted: know how (conocimiento práctico), resort (complejo turísticoexclusivo), outdoor (al aire libre), club house (en un condominio, instalaciones recreativas de propiedadcompartida), lodge(hotel especializado para excursionistas de nivelsocioeconómico alto).

Lexicalgaps, i.e.the absence of an exact equivalent and the need to name a reality: netbook (computador portátil básico), jingle (canción breve y contagiosa con fines publicitarios), subprime (crédito de alto riesgo), commodity (materia prima semielaborada).

The press is a vehicle for public participation in decision-making processes leading to change, but also a vehicle for manipulating opinions or orienting expectations, and as such, it is a means for readers/speakers to decide what changes may suit them (i.e. whether to adopt the Anglicized language offered in the news stories), and what aspects of the foreign culture that those words carry they would like to make their own, although these processes are sometimes subliminal.

In addition, Diéguez (2004) sustains that Chilean speakers incorporate most Anglicisms into their repertoire for three main reasons: a) there are no equivalents in Spanish, b) the Anglicisms belong to certain jargons, or c) they are used simultaneously with a Spanish equivalent for meaning clarification. In this study, alternate use of an English word and its equivalent has also been observed.

It is very importantto analyze these motives in the ESL and ESP classroom as they may help learners to transfer knowledge of these lexical items to understand and produce texts in English.

The incorporation of Anglicisms in Spanish most likelyhas a direct relationship with globalization and the prevailing open-market economy model developed in Chile. Interestingly, the import of new advances usually implies not only the adoption of the objects, but also of their names, and even a tendency for consumerism. Anglo-Americanization and globalization go hand in hand, with the United States in a position of great influence on other countries not only with respect to their economy but also other aspects associated with it such asway of life, culture, system of values and even ways of thinking transmitted, for example, by the cinema.

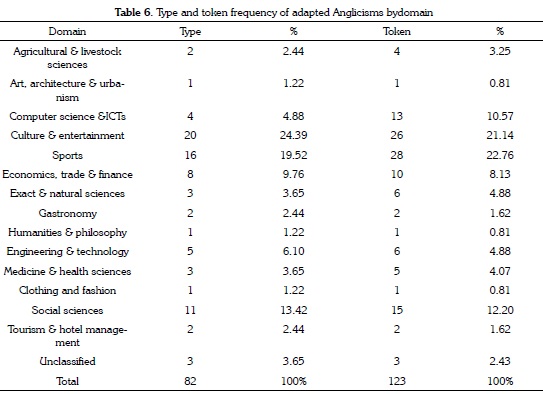

Adapted lexical units also concentrated in the areas of 'Culture & Entertainment,''Sports,' and 'Economy, Trade,& Finance,' and additionally, in'Social Sciences' (see Table 6). TheAnglicisms belonging to these areas constituted around 60% of alladapted English loanwords collected.

The fact that Anglicisms are adopted rather that adapted in Chilean Spanish makes it easier for learners of English to transfer them to their lexical repertoire in the target language. This availability needs to be assessed in the ESL/ESP classroom aslanguage awareness is a useful learning strategy.

Sáez (2005) argues that the process of incorporating Anglicisms in Chilean Spanish generally occursin specialized lexicons (sports, economics, finance, sciences, humanities, technology, music, the entertainment industry, communications, clothing, tourism and travel), sincetheyare probablyconstrained to one field, they are ephemeral,andare finally assimilated to everyday language.In accordancewith Fuentes, Gerding, Pecchi, Kotz,& Cañete (2008), the present studyreveals a certain degree of determinologizationand use stabilityover time, a process by which terminological usage and meaning trivializes when a term captures the interest of the general public, who gradually adoptit as their own.

Another study on loanwords in the press (Morin, 2006), which included eight Latin American countries (Chile among them), also shed light on the high rate of Anglicisms in Spanish from computer science and the internet. The results of the present study confirm previous findings by Sáez (2005) and Morin (2006) regarding the domain that imports the highest number of lexical units from English. According to these researchers, mass media in general, and the press in particular,play a role inthe transfer of Anglicisms to Spanish. In fact, journalistic language usually shows the linguistic changesin a community at a given time by incorporating new relevant items, discarding unfashionable ones, emphasizing specific uses, creating units, or explaining terms. The press is thus one of the most effective sources of lexical renewal in Spanish and a means of accounting forthe vitality of the language (Ortega, 2001). Other studies have also discussed the acculturating role of the press and the notion of social success associated to the incorporation of Anglicisms (Castañón, 2009; Sáez, 2005). However, the ultimate responsibility in the adoption of Anglicized forms fallsontext producers on the one hand, and on text consumers on the other.

A survey was conducted to assess the speakers'degree of familiarity witha selected number ofAnglicisms from the corpus. The criterion of neological feeling ('sentimiento de neologicidad' according to Sablayrolles, 2000)was used by the researchers to selectthe neologicalunits.Generally, there was a strong correlation with the "very familiar" recognition criterion of the 33 respondents. For example, all the respondents identified'chat,''facebo ok,''mall,'and'pendrive' as "very familiar." This result may be explained by the daily and widespread use of Anglicized items in computing. The word'mall,'in turn,is the most emblematic Anglicism representing American acculturation in Chile, as people have be-come used to spending much time in these American-looking shopping areas where a number of English words are used to advertise products and services. This fact may be a double-edged sword: on the one hand, Anglicisms might make English more accessible to ESL/ESP learners, but on the other, they may lead them into overuse of English lexical items and even the adoption of American traditions, such as Halloween, which has become a common celebration in Chile in the past few years. Certainly, cultural beliefs and values are embedded in language, and this may be one more way to establish cultural dominance.

A point in contentionis whether the staggering number of Anglicismswill continue to increase. Millán (2004) hypothesizes that preserving the use of thelanguage oracceptingthe creation of a 'new language' will depend on the users. Is itat all possibleor even convenient to avoid the incorporation of words from aninfluential foreign culture?Among others, the followingfactors should be taken into account:the prevalent economic development model, the increase of imported goods and the subsequent lexical gaps in the target language, globalized communication, user acceptance of Anglicisms without much questioning, an increasing need to learn English, and the absence of a national linguistic policy.

The impact of cultural alienation or enrichment (Márquez, 2006) on the language is still uncertain.As Millán (2004) puts it, future generations are likely to assimilate lexical blendalong with cultural invasion more naturally, without differentiating certain elements of the mother tongue from those of the imported language. This process, however, maylead toa significant loss of national identity, which underscores the need for an ad hoc linguistic policy. Due to the fact that languages, as living entities,have historically imported lexica, this borrowing processwillcontinueto developas long as all kinds of boundaries- the linguisticboundaryincluded - make this intercultural permeability possible.

As Gómez (2006) sustains, every individualshould take full responsibility for language use, and even though language teachers, journalists, linguists, terminologists,and translators are a minority among text producers, their decisions regardingusage have a direct effect on society and speakers' attitude towards the language.

From the ESL teaching viewpoint, the constant process of borrowing words may be an opportunity to highlight areas of comparison and contrast between English and Spanish lexical innovation. Hence the ESL classroomwill provide room for discovery and learning in vocabulary building using authentic textual material, especially in specific domains where lexical creativity is more fruitful.

Conclusion

It can be concludedfrom this study that the press is an extraordinary observatory that provides abundant data for the compilation and dissemination of lexical innovations. In this respect, the English language has had a strong influence on the word formation of the Chilean variety of Spanish today, as Anglicisms are frequently used not only to cover lexical gaps, but also when Spanish equivalents are available.

The fact that most Anglicismsfound areadopted neologisms, i.e. graphically unmodified lexical units incorporated to Spanish, usually in the form of nouns andwith no typographical marks, may indica-te, on the one hand,that speakers accept Anglicisms quite readily.This is most likelydue to the fact thattheyviewthe culture of English-speaking countries, particularly that of the USA, as more prestigious than their own. On the other hand, this influence seems to be an obvious consequence of the socioeconomic model imported from the USA, implemented in Chile in the mid-1970s, and still firm.Given the fact that Chile lacks a language policy to encourage maintenance of Spanish as the mother tongue, the incorporation of Anglicisms can be made straightforward to this variety.

Moreover, as the lingua franca of globalization, English has had an impact on the press due to the urgency to spread information. In this context, the role of the press in the incorporation of Anglicisms should be underscored,forthe press is believed to be an authoritative means to consolidate the use ofloanwords. Chile, one of the most open market economies today, trades in English, which surely contributes to familiarizing speakers with Anglicisms in certain domains closely related to worldwide economic and cultural exchange. Therefore, ESL teachers and translators should make students aware of the impact that this exchange has on the language, particularly in domains where Anglicisms are more abundant, e.g.computer science andICTs, culture andentertainment, sports, and economics, trade andfinance.

The relevance that the incorporation of Anglicisms has for translation lies withinthe dilemma facing the translator: either to choose Anglicized items to succumb to the pressure of information ubiquity by using calque or loanwords, or to translate them to Spanish to comply with target language standards and defend the linguistic patrimony. In this sense, students of translation should be made aware of their power to influence and educate their readers regarding language evolution and the importance of preserving the linguistic patrimony.

Teachers, translators, and journalists should be made aware of their responsibility in decisions concerning the incorporation of source language lexical units. These professionalsshould take into account that word borrowing is just one of the mechanisms used in Spanish to account for a new source language unit with no exact equivalent in the target language. In fact, more elaborated solutions, such as a descriptive equivalent, a functional solution,or even a new target language coinage are possible resources as well.

The extensive use of Anglicisms in the press and other mediareveals the hegemonic power not only of the English language as a global means of communication,but also of US culture worldwide, with subsequent consequences for the cultural identity and self-determination of the receiving culture, a fact that education, translation, journalism, and other policy-makers should bear in mind.

Notes

2 It belongs to the Grupo de Estudios Terminológicos, TermUdeC, Universidad de Concepción. Chile. Code: 03.F5.01, Dirección de Investigación.3 The international research project Antenas Neológicas is part of the Observatori de Neología (OBNEO) of the Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain.

4 By means of the Buscaneo, a semiautomatic neologism detector (Cabré and Estopà, 2009).

References

Abraham, W. (1981). Diccionario de terminología lingüística actual. Madrid: Gredos. [ Links ]

Adelstein, A., & Badaracco, F. (2004). Teoría lingüística y estudios neológicos. In Proceedings of the debates actuales international conference: Las teorías críticas de la literatura y la lingüística, 18-21. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires. [ Links ]

Alfaro, R. (1984). El anglicismo en el español contemporáneo. Thesaurus, 4(1), 102-128. Retrieved from http://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/thesaurus/pdf/04/TH_04_001_110_0.pdf [ Links ]

Cardona, G. R. (1991). Diccionario de lingüística. Barcelona: Ariel Lingüística. [ Links ]

Castañón, J. C. (2009). Los extranjerismos del deporte en español. Led on Line. Retrieved from http://www.ledonline.it/ledonline/index.html?/ledonline/429-linguaggio-sport-Hernan-Gomez.html. [ Links ]

Delgado, A. (2005). Los anglicismos en la prensa escrita costarricense. Káñina: Revista de Artes y Letras, 29, 89-99. [ Links ]

Diéguez, M. I. (2004). El anglicismo léxico en el discurso económico de divulgación científica del español de Chile. Revista Onomázein, 2(10), 117-141. [ Links ]

Domínguez, M. J. (2001). En torno al concepto de interferencia. Círculo de lingüística aplicada a la comunicación, 5. Retrieved from http://www.ucm.es/info/circulo/no5/dominguez.html. [ Links ]

European Union. (2011). Libro de estilo interinstitucional. Retrieved from. http://publications.europa.eu/code/es/es-000500.htm (original work published 2000). [ Links ]

Fontana J., & Vallduví, E. (1990). Mecanismos léxicos y gramaticales en la alternancia de códigos. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada. Anejo 1, 171-192. [ Links ]

Fuentes, M., Gerding, C., Pecchi, A., Kotz, G., & Cañete, P. (2008). Neología léxica: Prensa escrita y banalización de términos. In L. Fabbri (Ed.). XI Simposio Iberoamericano de Terminología (RITerm):La terminología en el tercer milenio: hacia la adopción de buenas prácticas terminológicas (13-16). Lima, Peru. Retrieved from http://www.riterm.net/article.php3?id_article=431. [ Links ]

Fuentes, M., Gerding, C., Pecchi, A., Kotz, G., & Cañete, P. (2009). Neología léxica: Reflejo de la vitalidad del español de Chile. Revista de Lingüística Teórica y Aplicada, 47(1), 103-124. [ Links ]

Fuentes, M., Gerding, C., Pecchi, A., Kotz, G. & Cañete, P. (2010a). Procesos de creación neológica en el español de Chile. In Colegio de Traductores Públicos de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires (Eds.). Actas V Congreso Latinoamericano de Traducción e Interpretación.(1216) [CD-ROM]. Buenos Aires, Argentina: CTPBA. [ Links ]

Fuentes, M., Gerding, C., Pecchi, A., Kotz, G. & Cañete, P. (2010b). Neología léxica ¿correo electrónico o email? In L. Fabbri (Ed.). XII Simposio Iberoamericano de Terminología (RITerm). (14-17). Buenos Aires, Argentina. Retrieved from http://www.riterm.net/article.php3?id_article=431. [ Links ]

García, V. (1989). Teoría y práctica de la traducción: Tomo I (2nd ed.). Madrid: Gredos. [ Links ]

Gerding, C., Fuentes, M., & Kotz, G. (2012). Anglicismos y aculturación en la sociedad chilena. Onomázein,25(1), 139-162. [ Links ]

Gómez, A. (2006). Un nuevo lenguaje técnico: El español de las redes mundiales de comunicación. En A. Gómez (Ed.). Donde dice... debiera decir...: Manías lingüísticas de un barman corrector de estilo. (139-154). Buenos Aires: Editorial Áncora. [ Links ]

Guerrero, G. (1997). Neologismos en el español actual (2nd ed.). Madrid: Arco Libros S.A. [ Links ]

Haensch, G. (2005). Anglicismos en el español de América. Revista Estudios de Lingüística Universidad de Alicante, 19, 243-251. [ Links ]

Lázaro, F. (1983). Diccionario de términos filológicos. Madrid: Gredos. [ Links ]

Márquez, M. (2006). Los anglicismos terminológicos integrales en los textos especializados del español. Estudios de Lingüística Aplicada, 24(43), 11-29. [ Links ]

Mazzo, R. (2008). Cómo se inserta Chile en un mundo globalizado. Retrieved from http://www.bcn.cl/de-que-se-habla/globalizacion-chile. [ Links ]

Millán, R. (2004). Uso de extranjerismos en la prensa venezolana y española: Español o inglés, el respeto al idioma. El cajetín de la Lengua.Retrieved from. http://www.ucm.es/info/especulo/cajetin/extran.html. [ Links ]

Morin, R. (2006). Evidence in the Spanish language press of linguistic borrowings of computer and Internet-related terms. Spanish in Context, 3(2), 161-179. [ Links ]

OBNEO: Observatori de Neologia. (2003). Protocolo de vaciado de textos de prensa escrita. Barcelona: Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada [mimeo] [ Links ].

Orellana, M. (1987). La traducción del inglés al castellano. Guía para el traductor. Segunda edición. Santiago: Editorial Universitaria. [ Links ]

Ortega, M. P. (2001). Neología y prensa: Un binomio eficaz. Espéculo: Revista de Estudios Literarios, 18. Retrieved from http://www.ucm.es/info/especulo/numero18/neologism.html. [ Links ]

Perdiguero, H. (2003). Innovación léxica en prensa. In Perdiguero & Álvarez (Eds.). Proceedings of the XIV ASELE international conference: 10-13 September 2003(pp. 88-95). Burgos, Spain: Centro Virtual Cervantes. Retrieved from http://cvc.cervantes.es/ensenanza/biblioteca_ele/asele/pdf/14/14_0089.pdf. [ Links ]

Universia (n.d). Retrieved from http://internacional.universia.net. [ Links ]

Ritzer, G. (2002). Teoría sociológica moderna. Madrid: Mc-Graw Hill. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, C. (n.d.). Los idiomas y su importancia en el proceso de globalización. Retrieved from http://www2.csusm.edu/languages/idiomas.doc. [ Links ]

Sablayrolles, J. F. (2000). La néologie en français contemporain: Examen du concept et analyse de productions néologiques récentes. Paris: Honoré Champion. [ Links ]

Sáez, L. (2005). Anglicismos en el español de Chile. Revista Atenea, 2(492), 171-177. [ Links ]

Sáiz, F. (2001). El lenguaje en el periodismo económico, o cómo no gatillar el repo. Proceedings of the II Congreso Internacional de la Lengua Española: El español en la sociedad de la información: 16-19 October 2001. Valladolid, Spain: Real Academia Española & Instituto Cervantes. Retrieved from http://congresosdelalengua.es/valladolid/ponencias/el_espanol_en_la_sociedad/1_la_prensa_en_espanol/saiz_f.htm. [ Links ]

Samsing, F. R. (2008). Modelo económico de libre mercado vigente en Chile. Revista Realidades, 106. Retrieved from http://www.realidades.cl/?p=106. [ Links ]

Zhou, C., & Yajun, J. (2004). Wailaici and English borrowings in Chinese. English Today, 20, 45-52. doi:10.1017/S0266078404003086. [ Links ]

Dictionaries cited

Battaner, M. P. (2001). Diccionario de la lengua española: LEMA (1st ed.). Barcelona: Spes Editorial. [ Links ]

Battaner, M. P. (2002). Diccionario de uso del español de América y España: VOX (1st. Ed.). Barcelona: Spes Editorial. [ Links ]

Cambridge Dictionaries on line. (2013). Retrieved from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/. [ Links ]

Merrriam Webster's Dictionary (2013). Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com. [ Links ]

Real Academia Española. (2001). Diccionario de la lengua española (22nd ed.). Retrieved from http://www.rae.es. [ Links ]

The Free Dictionary. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.thefreedictionary.com. [ Links ]

Word Reference, Online Language Dictionaries. (2013). Retrieved from. http://www.wordreference.com. [ Links ]

THE AUTHORS

CONSTANZA GERDING SALAS, Ph.D., English teacher and Associate Professor at Facultad de Humanidades y Arte in Universidad de Concepción. B.A. in Education from Universidad Austral de Chile, Graduate Diploma in English-Spanish Translation from Escuela Latinoamericana de Traductores e Intérpretes, Santiago, Chile; and Doctor in Education from Stockholm University and Universidad de Concepción, Chile.

MARY FUENTES MORRISON, B.A. in Humanities, M.A. in Linguistics from Universidad de Concepción, and M.A. in French Language and Civilization from Paris Sorbonne University. She is an Associate Professor at Facultad de Humanidades y Arte in Universidad de Concepción (retired).

LILIAN GÓMEZ ÁLVAREZ, B.A. in Education, M.A. in Linguistics from Universidad de Concepción, Chile; and Ph.D. in Education and Human Sciences from University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA. She is an Associate Professor at Facultad de Humanidades y Arte in Universidad de Concepción.

GABRIELA KOTZ GRABOLE, Ph.D., M.A. in Applied Linguistics and Doctor in Lingusitics from Universidad de Concepción, Chile. She is an Assistant Professor at Facultad de Humanidades y Arte in Universidad de Concepción.