Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

versión impresa ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.19 no.2 Bogotá jul./dic. 2017

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.57178

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.57178

Making Sense of Alternative Assessment in a Qualitative Evaluation System

Entendiendo los procedimientos alternativos de valoración de desempeño en un sistema de evaluación cualitativo

Javier Rojas Serrano*

Centro Colombo Americano, Bogotá, Colombia

This article was received on April 4, 2016, and accepted on October 20, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA, 6th ed.):

Rojas Serrano, J. (2017). Making sense of alternative assessment in a qualitative evaluation system. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 19(2), 73-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.57178.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

In a Colombian private English institution, a qualitative evaluation system has been incorporated. This type of evaluation poses challenges to students who have never been evaluated through a system that eliminates exams or quizzes and, as a consequence, these students have to start making sense of it. This study explores the way students face the new qualitative evaluation system and their views on alternative assessment as a way to help them make headway with their English learning process.

Key words: Alternative assessment, qualitative evaluation, quantitative evaluation.

En una institución educativa privada dedicada a la lengua y la cultura inglesas en Colombia, se incorporó un sistema de evaluación cualitativo para ayudar al estudiante a alcanzar sus metas de aprendizaje. Este sistema plantea desafíos a los estudiantes que nunca han sido evaluados con un modelo sin exámenes escritos y, como consecuencia, tienen que desarrollar una serie de habilidades para entenderlo. Este estudio explora la manera como los estudiantes se enfrentan al nuevo sistema de evaluación y su opinión sobre este respecto a su proceso de aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: evaluación cualitativa, evaluación cuantitativa, métodos alternativos de valoración.

Introduction

One of the main difficulties of a qualitative evaluation system, like the one adopted by the Adult English Program in the Centro Colombo Americano - Bogota, is facing a student who fails a course or who passes with some difficulties and still does not totally accept that he or she needs to keep improving. Convincing a failing student as to why he or she must repeat a course is a hard task because in a qualitative approach to evaluation, sometimes clear evidence is not recorded, stored, or managed, and evaluation ends up looking like just the teacher's gut feelings on paper. The same happens with students who pass with the minimum performance required and, as they pass, do not feel they need to keep working hard in certain areas. On many occasions, they might even feel that they did not deserve to pass, contrary to what his/her teacher decided. Most of these concerns usually come from students who have always been evaluated by specific numbers or through products like final outcomes, exams, or quizzes and would rather see this type of evaluation in the Colombo as well.

However, this end-of-the-cycle dilemma need not be a nightmare provided that students who are not familiar with the qualitative evaluation system understand how it works and what practices are behind the teacher's decision to fail or pass a student. This research project intends to understand how students make sense of and try to adapt to a qualitative evaluation system, which would eventually avoid traumatic experiences on the side of the teacher as well as of students themselves in light of the different assessment tools offered by the program.

Even though this type of dilemmas may not apply to most English teaching departments and institutions, in the sense that most places continue approaching evaluation from a quantitative system which offers less controversy and more practicality at the moment of grading students, at the Centro Colombo Americano - Bogota, the qualitative system of evaluation is being constantly revisited and discussed in order to help the faculty and the students get a grip on it. The fact that most students and teachers in the program come from quantitative backgrounds—from our schools and majors to our latest work experience—poses specific challenges and threats that make this type evaluation difficult to follow because it regards attitude, culture, task accomplishment, and the whole process and does not consider quizzes and exams.

After having undergone several feedback sessions with students, the same questions keep on popping up. As a matter of fact, these questions have eventually become the research questions leading this study:

- How do students coming from a quantitative evaluation background respond to a qualitative evaluation system?

- How do students make sense of the alternative assessment activities that teachers plan in order to draw conclusions about their own performance?

At first glance, these objectives lead us to think that possible research constructs are the quantitative evaluation system most students are familiar with, the new qualitative evaluation system used by the Colombo, and the students' reflection, analysis, and final reaction towards the new system.

Literature Review

Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Evaluation

In spite of the fact that this issue may seem new or even restricted to the Centro Colombo Americano scenario, a lot of related literature and theory have been spread and dealt with for some years now in the education field.

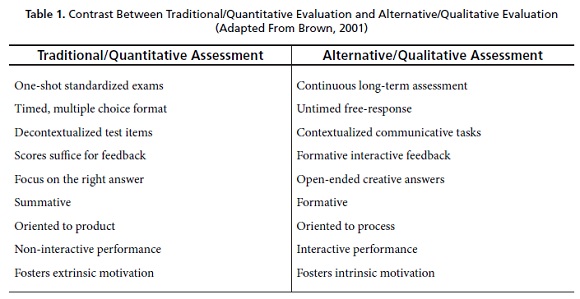

Teachers at the Centro Colombo Americano have gradually become more and more confident evaluating students through a qualitative system, but it is also true that for many of us at the beginning, it was a real challenge to get used to it. In fact, it is still hard in some cases to make up one's mind as to who is passing or failing a course, given the fact that there is still an inner struggle between the teacher's quantitative background and the current qualitative practice. This inner struggle may come from the benefits we see in both systems that are summarized by Brown (2004), who points out that while traditional-quantitative evaluation provides higher practicality and reliability, alternative-qualitative systems provide better washback and authenticity.

Nevertheless, an aspect that may add up to the difficulties in implementing a qualitative approach to evaluation is explained by Cohen (1994), who suggests that "people have reached a spoken or unspoken agreement that traditional methods look like the right way to assess. In fact, teachers may choose methods that reflect the way they were assessed as students (p. 29)."

This situation, however, has not only been faced by the Centro Colombo Americano. Brown (2004) argues that approaches to evaluation in different institutions worldwide have shifted focus onto a more alternative view of evaluation and have become distanced from traditional evaluation systems because alternative ways of evaluation foster assessment tools that can be extended to real life, are more meaningful, and regard the products as well as the process. In addition, non-traditional assessment that might not look like testing (with all the stress and anxiety that it carries), provides space for students to develop their creativity, increases critical thinking skills, and enables more multicultural connections (Brown, 2004). This view is evident when we regard the products, tasks, and projects that students carry out in our institution. However, the same author insists that non-traditional and qualitative assessment requires considerable time and effort on the part of teachers and might look less convincing to students.

Another aspect to consider when defining traditional-quantitative and alternative-qualitative approaches to evaluation has to do with what is done with the information obtained. The discussion, then, as proposed by Areiza Restrepo (2013), focuses on formative as opposed to summative assessment if we consider the purpose of it. Traditional evaluation tends to render summative assessment in the sense that the information collected is used to decide who passes or fails and based on the quizzes or exam results, the student should draw conclusions about what language aspect to review and reinforce. A qualitative assessment system, on the other hand, goes beyond and, additionally, produces feedback that will help students identify strengths or weaknesses through a conference with the teacher in which all aspects of the learning process are discussed; apart from the use of language, these aspects also include the areas that cannot be covered in an exam and are connected to the ability to implement learning strategies throughout the process, team work abilities, use of resources, punctuality, and so on. This type of assessment is therefore more realistic and authentic in the sense that to be successful in real life the mere knowledge of a language is not enough, but that a wider set of social and organizational skills is needed along with it.

Table 1, taken from Brown (2001), summarizes the most important characteristics of the quantitative and qualitative approaches.

Students' Awareness and Reflection on Alternative Assessment

I have mentioned that the formative and summative assessment discussion is at the core of the analysis of quantitative and qualitative evaluation approaches. Areiza Restrepo (2013) points out that whereas summative assessment is designed to determine whether students have achieved the goals of the program by the end of a cycle or the course, formative assessment is, conversely, designed to be diagnostic, remedial, regulatory, and ongoing. Therefore, at a first glance, we may infer that summative assessment provides a kind of reflection in which students, instead of planning actions to improve, may end up just showing regrets about the things they did wrong or did not do at all, whereas formative assessment gives students the opportunity to come up with action plans to keep their strengths and to tackle their weaknesses timely. This conclusion was actually drawn from his study in which participants, after being exposed to formative assessment actions, showed their abilities to identify and understand their strengths and weaknesses. This situation eventually led students to enhance their learning and have a sense of success.

Similarly, a study carried out by Baleghizadeh and Zarghami (2012), in which Iranian students were introduced to conferencing as a formative assessment tool, showed how these students got better results on a grammar test than the ones who were not exposed to teacher-student conferences during their process. It is explained by the researchers that the differing results between the two groups of students have to do with the fact that the students who were involved in conferencing as an alternative way of assessment were encouraged to take more responsibility for their process by self-assessing, reflecting, monitoring, and setting goals to improve their learning.

However, in spite of the deep understanding of formative assessment and practices shown by the aforementioned authors, the programs in which their studies are framed still evaluate students through final exams that are the ultimate tools that teachers use to let students pass a course, no matter how much reflection, awareness, and action planning the formative practices that they implemented rendered.

When eliminating exams and quizzes, as is the case of the program in which the present study takes place, teachers and students have to rely entirely on formative assessment tools, and this is what makes this paper singular and novel and what gives relevance to the research questions that this study proposes.

Research Context

The program in which this study was carried out is made up of 18 levels from basic to advanced English. Each level lasts one month approximately and covers between three and four content units. At the end of each unit, students develop a task in which they show their understanding and mastery of the vocabulary, grammar, and strategies learned throughout the unit; they are designed to establish connections between what has been learned and students' reality. These tasks are usually filed in a portfolio or uploaded to an online group together with reflections, peer-assessment, and self-assessment notes. Every unit or two, teachers usually have conferences with students to brief them about their progress in the course in aspects as varied as communication, teamwork, punctuality, use of strategies, class performance, and homework development. At the end of each cycle, a final student-teacher conference takes place in which the student's progress is discussed. With this evaluation system, more often than not, students know if they are passing or failing before this final conference and this moment becomes a way to offer students suggestions and advice on what to focus on and how to keep improving. However, sometimes, students also object to the teacher's decisions because, from their viewpoint, they made good progress and deserve to pass, and a quantitative evaluation tool has not been used to end such controversy with a clear number or letter and mistakes highlighted on an exam or quiz.

Research Framework

This research project may be connected to what scholars have called case study. Even though it would have been desirable to have carried out changes and innovations in pedagogical activities, which is the ultimate goal of action research, in our particular case it was also important to understand the problem in depth before moving on to an intervention.

Case study, as defined by Stake (1999), allows the study of the "peculiarity and complexity of a singular case in order to figure out its activity in important circumstances" (p. 15). This way, the peculiarity and complexity of a restricted group of students from a restricted number of courses may provide us with important data to understand how a bigger number of students from a wider range of course would react in the face of a different evaluation system from the one they are used to.

Methodological Design

For the sake of this research study, seven people were selected as participants and were asked to fill out the corresponding consent form. This selection was made taking into consideration the level of students, and their being newcomers to the Colombo. It was considered that students in intermediate and high intermediate levels could offer more elaborated insights since they may have more academic experience than others and some of them may have even studied abroad. Most participants were studying in either undergraduate or graduate programs by the time of this research and just a few had already graduated. Thus, participants had enough experience with quantitative evaluation that may contrast with the type of evaluation carried out at the Centro Colombo Americano- Bogota.

On the other hand, participants needed to be newcomers in the institution, since the study intended to find out how these students, coming from a quantitative evaluation tradition, adapt to and assimilate a qualitative evaluation system.

Participants were coded as follows: Two intermediate students = Sk1 and Sk2. Five high intermediate students = Ch1, Ch2, Ch3, Ch4, and Ch5.

To avoid confusion, readers just need to know that a code with Sk belongs to an intermediate level (between A2 and B1 in the Common European Framework [CEF]) and a code with Ch belongs to a high intermediate level (about to get a B2 in the CEF).

Data Gathering Techniques

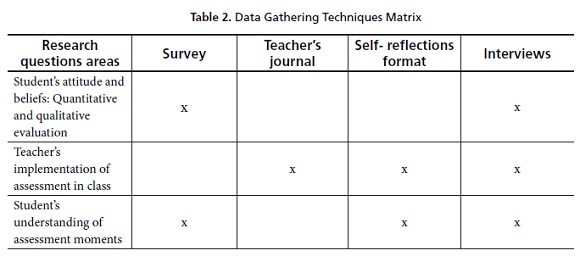

The matrix in Table 2 represents the different data gathering techniques and the areas and questions of this research that were addressed with each of them.

In order to account for these research variables and to eventually tackle the research questions, four different data gathering techniques were implemented in three different groups and applied to the aforementioned population.

Data gathering technique 1: The survey. The survey1 intended to explore students' beliefs and opinions about quantitative and qualitative types of evaluation and with which ones students were more comfortable, taking into consideration their academic life experience. These are the survey questions that were answered by two low intermediate and five high intermediate English students:

- Taking into consideration your academic process during your life (High School, College), what type of evaluation are you more familiar with?

- Do you think that having a specific grade (Letter or Number) reflects clearly the knowledge you have acquired in any course?

- Apart from having a specific grade (number of letter), what other type of evidence of your progress can be shown?

- Would you feel more comfortable if the Colombo evaluated all levels with a final exam, or if homework, activities, and projects were assessed every single class?

- For your own academic progress, which type of evaluation would you consider the most beneficial one?

- After having finished a level in the Colombo, do you consider that you understand the evaluation system in this institution?

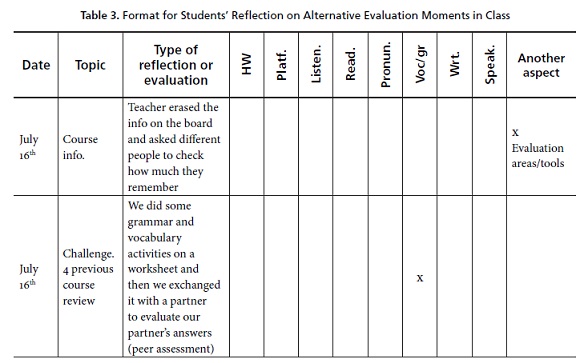

Data gathering technique 2: Teacher's journal. A journal in which assessment and evaluation moments were recorded for every class was kept. From day 1 to day 19 (the length of a level in the Colombo), assessment moments that were planned in every single lesson were recorded daily in this journal in order to compare these notes with the assessment moments that students identified and recorded in the self-reflection form that was given to the participating students for them to keep track of these classroom activities.

Data gathering technique 3: Artifact (self-reflection form). The participating students were asked to complete a format in which, on a daily basis, they had to write down moments of evaluation that they were able to identify. At the end of the class, students stayed for five more minutes in class to complete the entry of the day, in which they had to identify the nature of the assessment moment, the type of assessment tool, and the skills or areas of English that were assessed through that activity. Table 3 is an example of what students had to do with the format.

Data gathering technique 4: The interview. The final data gathering technique implemented in this study was a questionnaire. At the end of the second level with each group, participants were asked to answer a questionnaire in which they expanded on their opinion about the evaluation process and its results on their learning process. The questions posed were:

- You have already finished two courses of English in the Colombo. Have you been able to identify evaluation moments during the class that were guided by the teacher? What moments, in which you have been encouraged to reflect upon your own performance, can you mention?

- Which of these activities have helped you understand your performance in class?

- Have you missed the numbers or letters to have an idea of what you need to improve and what you are doing ok? Why?

- Without taking into consideration the establishment of partial or final exams, what kind of evidence could be used to improve the type of evaluation in the Colombo?

Validity and Reliability

The validity and reliability of the study are assured by the synergy among the different data gathering techniques. They account for both the participants and the teacher-researcher's views, and were also designed in such a way that one technique is backed up by another when considering the different variables or constructs of the study, as shown in the Data Gathering Techniques Matrix (Table 2). This provides this study with reliability. In addition, validity is also present because the techniques that were selected and designed tackled the concerns that arose from the questions and variables of the study.

Data Analysis and Results

After the analysis of the information collected through the different gathering techniques used, three salient aspects emerged. These categories are directly connected to the research variables that were identified at the beginning of this study: Qualitative evaluation, quantitative evaluation, and the students' reflections on alternative assessment.

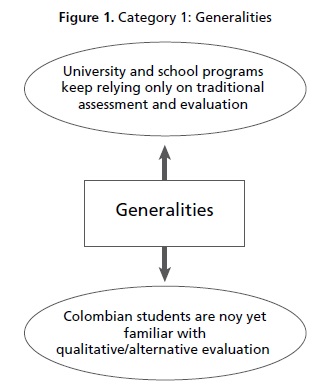

Category 1: Generalities

In the Colombian context, it is thought that the quantitative approach is the one by which most academic institutions are driven when evaluating students, and this view is actually supported by Areiza Restrepo (2013). In his study, he found research that unveiled the lack of knowledge and instruction on formative assessment of Colombian teachers who did not regard assessment as a way to enhance learning but just as a way to decide who passes or fails a course. Among other reasons, he found out that it might be happening because, in general, only a few universities actually offered instruction in this type of evaluation to language teachers. This perception was confirmed through the answers the participants in this study gave in the survey. It was noticed in the survey that all participants were given grades, be it with numbers or letters, that provided a concept of a final product, and that just a few of them recognized that their process was also taken into consideration in previous academic experiences.

Also, in students' previous experience, important learning aspects such as attitude, punctuality, commitment, leadership skills, and group work abilities were more often than not disregarded or not seen as important as a final product, even though getting to a product involves a good performance in the areas mentioned above. It is mentioned by one student who wrote on the survey that in his previous learning experiences, before getting to the Centro Colombo Americano, "many things are left aside such as participation, the learning process, and the attitude in class" (Ch3).

In some other cases, students recalled having received feedback about their commitment in the activities, but it was not as specific as they found it in their Colombo course:

In the school, our commitment was evaluated, but it was not as specific as it is here...I mean, here, we are reminded of how many times we came to class, how many absences, how our performance in class was, if I could handle the grammar, If I got the listening, and many other things that add up to a more comprehensive evaluation...at school, we were evaluated mostly through exams. (Ch3)

Figure 1 is a summary of the generalities that were identified through the analysis of the data collected during the research process.

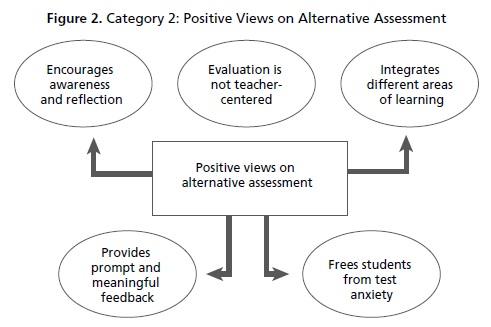

Category 2: Positive Views on Alternative Assessment

After being exposed to the qualitative evaluation carried out at the institution through the use of alternative assessment procedures, most students could identify some benefits and positive aspects that this type of evaluation has on students' performance. For example, Ch3 said in the survey that she had not missed exams in the Colombo because "instead of a number, a cold, dry number," she is getting feedback about what aspects to improve in a more specific and meaningful way.

The new evaluation system places new students in a new setting that they had to make sense of. Despite this, students seem to adapt and get alternative assessment in a good way. At the end of the day, students liked the fact that they could identify their strengths and weaknesses without having to take an exam, and that actually, they could identify issues that go beyond grammar and vocabulary. In this sense, the tasks and presentations were regarded as the most important activities to help students with their assessment.

In the interview, Ch3 says, for instance, that:

I feel that the activities that made me understand the most, or the ones that helped me the most were the presentations because they were the most complete way to have look at everything, the grammar, the vocabulary, as well as the expressions, using everyday language, and seeing every single thing...also, the feedback from our partners was really nice.

Ch4 and Sk1 had a similar impression in the interview:

The presentations...for me, it was really difficult to stand in front of different people to present a specific topic, especially in English, but it helped me know how much I really learned. (Ch4)

Something that was very important for my evaluation, was the presentation because it was OK and I got important feedback about it from my teacher and classmates. (Sk1)

In the survey, some students acknowledged some of the strategies they have gradually developed in order to look for ways to improve. To come to this point, class routines and assessment-based activities played an important role. When asked what evidence of progress they had, most participants highlighted the fact that they paid special attention to their teachers' feedback, carried out self-assessment and self-monitoring, and compared themselves to other members of the class without being necessarily given direct information about their performance from the teacher but also from other students and from self-reflection.

Students also thought that qualitative assessment frees students from anxiety and pressure and that is why traditional exams do not provide them with real information about their performance, as Sk1 put it:

I think that exams generate pressure in the student and, actually, they do not render good evidence about the real class performance. (Sk1)

One of the most common benefits students acknowledge as regards the qualitative approach to evaluation is the opportunity to reflect upon one's own process; this reflection was encouraged by the practices and routines that teachers following a qualitative approach have.

Through the interview, students identified some of those practices and activities that helped them self-reflect:

Well, during the class we would always do some periodic reviews as the units and lessons went by...also, the tasks we had to do, the presentations...all in all, it helped me reflect upon my own performance. (Ch3)

For instance, activities were as simple as a couple of questions; however, in those two questions, one—not even the teacher—knew how much one learned, how well one could handle the grammar, and express it naturally. (Ch4)

I think that in all activities we did, we assessed ourselves and did not simply went on with the next activity, but we shared results, evaluated the results, and each student was perfectly capable to identify which his/her mistakes had been and how to improve them. (Ch1)

Finally, most of the participating students (5 out of 7 in the survey) agreed that they would prefer a type of evaluation in which everything they do is taken into consideration rather than having only exams and quizzes.

Figure 2 puts together the positive views students showed through the data gathered in this study.

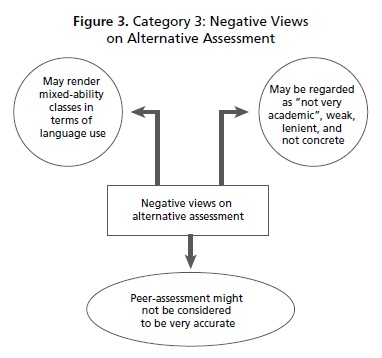

Category 3: Negative Views on Alternative Assessment

A disadvantage some students mentioned about a qualitative approach to evaluation is that in some cases students with mixed language levels may end up in the same class. It might be due to the fact that when you assess the process and the product, as a teacher following a qualitative approach, you have to consider the effort students put into it, the commitment they showed, and the time they devoted, and not only the quality of the product. On the other hand, if a student who did not follow any process or show evidence of ongoing work displays a great product, he might eventually fail the task because of not following the steps to complete the activity, even if the final product is really good. This situation was perceived by a student who said in the interview:

I think that the students that have had very good teachers have learned a lot, and if they had to take an exam from which their passing or failing depended on they would have passed anyways and it would be a waste of time. But also, there are people that, in spite of being very responsible, have some language flaws and for them it would have been good to repeat at least one course for them to identify those flaws and work on them, since those gaps in their knowledge may make them confused for the rest of the process (Ch1)

Through the analysis of the information obtained, there seems to be an agreement that numbers or letters do not quite represent accurately how much and how well a student is learning. However, some of them still miss having exams and quizzes to have a more "accurate" report on their performance. Some students brought up in the survey that a qualitative approach to evaluation may be too flexible and lenient and it might not offer concrete evidence to students. Some of the participants thought that giving exams may expose students to more academic challenges, as this student put it in the survey:

I feel that something clearer is necessary to get my process assessed in a more concrete way and to put students in front of a more academic challenge. (Ch2)

In the interview, Ch1 also acknowledged that:

I'm not a friend of exams, being a teacher myself, and I'm not a friend of giving exams all the time as well to determine if a student is passing o[r] failing, but I think that every now and then it is necessary to give an exam from which evidence is taken to decide whether a student is passing or not...in the two levels I've studied in the Colombo, people have different levels of English.

This situation, of course, makes some students feel suspicious about some other alternative assessment practices such as peer-assessment, in which students have to assess other students' performance, because, in their view, it makes no sense to get feedback from a student who may have even more language difficulties than the ones they have.

Figure 3 shows a summary of the negative views on alternative assessment that some of the students involved in this study identified.

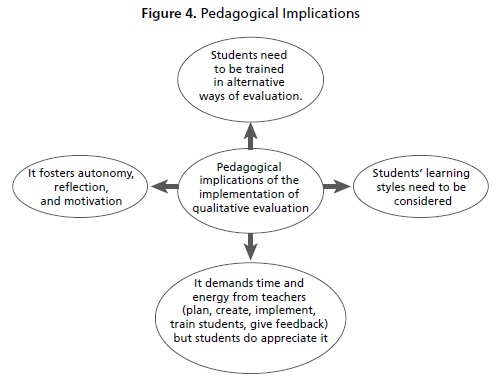

Pedagogical Implications

Every time a new course starts, students are explained what the evaluation is going to be like. They are told that there will not be exams or quizzes and that all they do day by day will be taken into consideration in order to decide whether they are passing the course or not. Some of them show a big smile when they hear about the exams policies and think that the course is going to be a piece of cake. However, when they realize that they not only have to demonstrate understanding of grammar and vocabulary every now and then on a piece of paper but in every single activity, every single day, and that they also have to show communication skills, punctuality, acquisition of daily learning habits, and social and teamwork skills, some of those smiles start to fade away. Some students adapt to the new system easily and naturally, but others have some trouble assimilating it. As Tedick and Klee (1998) put it, students need extensive training and preparation to adapt to alternative assessment. Lots of guidance is required for students to start reflecting upon their own process from a critical standpoint, to be able to think of a clear action plan, and to offer feedback to others as well. However, when students are constantly trained, they are capable of identifying moments of assessment and making the most of them, as was evident in the forms they had to fill out after each class to identify moments of evaluation throughout the lesson.

In this study, we intended to explore these students' beliefs and feelings towards the qualitative approach to evaluation and to understand how well they adapt to it. From the analysis of the data collected in this research study, these ideas can be drawn:

Students appreciate being given specific feedback about their performance in different areas of the learning process in an ongoing fashion.

Some students do not miss the quantitative grades they used to get in other academic programs. A few of them, however, believe that sometimes a traditional way to assess students' performance is still necessary, particularly to bridge the gaps of grammar and vocabulary among students who are in the same course but show some differences in their English proficiency.

After proper and ongoing training, students are able to identify and use assessment moments to spot their own strengths and weaknesses.

Sometimes students' assimilation of alternative assessment depends on their cognitive style. Students who have an analytical learning type, who are more independent, autonomous, and logical may feel more comfortable with the new system because they can use their classmates' and teacher's feedback to create action plans and strategies to solve problems as they go through the learning process. On the contrary, students with an authority-oriented learning type tend to be more structured and traditional. Therefore, they may feel more comfortable being assessed through more formal tools and being told exactly what to do to increase their numbers.

On the teacher's side, a qualitative approach to assessment and evaluation poses more challenges than a quantitative one. According to Brown (2001), quantitative approaches are meant to be highly practical and time-saving, offering standardized kinds of assessment to every student in a class or a school at the end of each term. On the other hand, the same author explains that qualitative assessment and evaluation demand a continuous effort from teachers to assess, evaluate, and give feedback to students on a more regular basis, which is time-consuming and not practical at all, although it turns out to be more beneficial to students, who can take actions to tackle learning issues on the go and not when there is not much to do. Moreover, teachers need to learn to be more organized and responsible in order to be able to give prompt and comprehensive feedback, especially to those students who are struggling to meet the course goals. As teachers—not grades—have to talk to students, they are to be assertive and straightforward, but, at the same time, supportive and polite. The adaptation to a qualitative system is then not only a student but a teacher matter as well.

Figure 4 summarizes the pedagogical implications that emerged out of the data gathered throughout the research process.

Further Research

This study has focused on understanding students' beliefs and adaptation processes to the qualitative approach to evaluation and has not considered the actions taken in order to make such an adaptation easier. Given this fact, it would be interesting to explore some of those actions and the artifacts teachers create in order to facilitate the assimilation of this approach by newcomers. This way, we could have a closer view on qualitative assessment tools and their effectiveness, the actions taken by teachers before, during, and after the feedback conferences with students in order to make sure they help students improve troublesome areas, or the use of self and peer assessment moments and how to make them more effective. In other words, it is hoped that this reflection and descriptive paper can render a number of action research projects in which senior and junior teachers facilitate the transition of new students from a traditional to an alternative system of evaluation and assessment.

Conclusion

No educational endeavor can be understood without the evaluation process that measures its results. In fact, the evaluation approach has to mirror the curriculum in which it is used. Language learning has undergone great changes throughout the years (from the grammar-translation method to the more communicative approaches) but, apparently, evaluation and testing still rely on exams and quizzes to get an idea of students' progress. Nowadays, language learning demands a wider range of skills that surpass grammar, vocabulary, and communication, and also cover the ability to learn autonomously, to use technology, to select and apply learning strategies, to collaborate with others, and to establish social and cultural bonds, which are areas that cannot be measured and observed by means of traditional evaluation tools. It is hoped that this paper reached its goal to show what students think and how they react when confronting an alternative evaluation system that is entirely different from what they heretofore had known in their academic life but that is thought to be more coherent with the areas that new language teachers need to observe and assess.

1Survey and interview questions and answers have been translated from Spanish for publication purposes.

References

Areiza Restrepo, H. N. (2013). Role of systematic formative assessment on students' views of their learning. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Development, 15(2), 165-183. [ Links ]

Baleghizadeh, S., & Zarghami, Z. (2012). The impact of conferencing assessment on EFL students' grammar learning. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Development, 14(2),131-144. [ Links ]

Brown, D. H. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2nd ed.). New York, US: Pearson Longman. [ Links ]

Brown, D. H. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and practices. New York, US: Pearson. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. D. (1994). Assessing language ability in the classroom. Boston, US: Heinle. [ Links ]

Stake, R. E. (1999). Investigación con estudio de casos [Case study research]. Madrid, ES: Morata. [ Links ]

Tedick, D. J., & Klee, C. A. (1998). Alternative assessment in the language classroom. Washington D.C.: Center for International Education. [ Links ]

About the Author

Javier Rojas Serrano holds a BA in Philology and Languages from Universidad Nacional de Colombia. He has been an English teacher, a supervisor, and an assistant coordinator at Centro Colombo Americano, Bogotá. He has also published articles related to technology, teacher collaboration, and citizenship in the English classroom.