Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

International Law

versión impresa ISSN 1692-8156

Int. Law: Rev. Colomb. Derecho Int. no.25 Bogotá jul./dic. 2014

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.il14-25.ifor

INDICATORS AS A FORM OF RESISTANCE COLOMBIAN COMMUNITY MOTHERS: AN EXAMPLE OF THE GLOBAL SOUTH'S USE OF INDICATORS AS A COUNTER-HEGEMONIC GLOBAL DOMINANCE TECHNIQUE*

INDICADORES COMO FORMA DE RESISTENCIA LAS MADRES COMUNITARIAS EN COLOMBIA COMO EJEMPLO DEL USO DE INDICADORES EN EL SUR GLOBAL COMO UNA TÉCNICA DE DOMINACIÓN CONTRAHEGEMÓNICA

Lina Buchely**

*This study was made possible by the financial support of the International Research Development Centre (IDRC), of Canada, under the project Global Administrative Law: Improving Inter-institutional Connections in Global and National Regulatory Governance. Project number: 106812-001.

**Lawyer, political scientist, LLM and Ph.D. in Law at Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. LLM from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Full time professor at Universidad ICESI, Cali, Colombia. Contact: lfbuchely@ICESI.edu.co

Reception date: May 8th, 2014 Acceptance date: June 30th, 2014 Available Online: September 30th, 2014

To cite this article / Para citar este artículo

Buchely, Lina, Indicators as a Form of Resistance. Colombian Community Mothers: An Example of the Global South's Use of Indicators as a Counter-HegemONIC Global Dominance Technique, 25 International Law, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, 225-266 (2014). http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.il14-25.ifor

Abstract

Whereas mainstream critical literature affirms that indicators are a new global form of North-South domination, people in the global south do not experience these indicators as such. In some ways, some social movements have used the discourse surrounding indicators to obtain monetary and symbolic capital. This article analyzes these indicators as a form of resistance, destabilizing traditional criticism of the discourse. The Community Mothers case study, developed between June 2012 and February 2013, shows how street-level bureaucrats use the indicators as an empowerment mechanism. The Community Mothers display an undocumented agency that develops a feminist agenda of helping fellow women, contrary to the government agenda that promotes childcare and the early childhood program policies. In this sense, the fieldwork undertaken portrays mothers and children as conflicting actors. Despite this, the social policy indicators hide this conflict reproducing the normative image that ideologically links mothers with their children. The results of this research project reveal, therefore, that the global south plays an unexpected role in the power dynamics inherent to the indicator. It presents a very different version of the history of global governance to the one that portrays unidirectional and structural domination offered by neocolonialism, in which the south always loses.

Keywords: indicators; feminist accounting project; community mothers

Resumen

Al paso que los textos críticos tradicionales afirman que los indicadores son una nueva forma de dominación del sur por el norte, las personas en el sur no experimentan estos indicadores como tales. En cierta forma, algunos movimientos sociales han usado el discurso que rodea a los indicadores para obtener capital monetario y simbólico. Este artículo analiza estos indicadores como una forma de resistencia, que desestabiliza la crítica tradicional del discurso. El caso de las Madres Comunitarias desarrollado entre junio de 2012 y febrero de 2013, muestra que los burócratas de la calle usan los indicadores como un mecanismo de empoderamiento. Las Madres Comunitarias muestran una agencia no documentada que desarrolla la agenda feminista de ayudar a las mujeres, contrario a la agenda gubernamental que promueve la asistencia a los niños y las políticas de programas de infancia temprana. En este sentido, el trabajo de campo llevado a cabo muestra a las madres y a los hijos como actores en conflicto. A pesar, los indicadores de política social ocultan este conflicto que reproduce la imagen normativa que vincula ideológicamente a las madres con sus hijos. El resultado de esta investigación revela por consiguiente, que el sur global juega un papel inesperado en las dinámicas de poder inherentes al indicador. Presenta una versión muy diferente de la historia de la gobernanza local respecto de aquella que presenta una dominación unidireccional y estructural ofrecida por el neocolonialismo en la que el sur siempre pierde.

Palabras clave: indicadores; proyecto feminista de cuentas; madres comunitarias

SUMMARY

Introdtjction.- I. Theoretical framework.- A. The Instrumentalized Minority or the Sommer's Argument.- B. Indicators as Resistance? The Third Wave in the Indicators Literature.- II. The Daily Experience of the Indicators: Local Space, Global Life.- A. TheArrivalof theFeministAccounting Project: An Approach to Analyzing the Regulation of Domestic Work in Colombia.- B. Colombia after the Care Economy Act.- C. The Community Mothers' Speech in Doris Sommer's Script.-III. Bad Mothers: Mothers and their Children in Social Policy Indicators.- Conclusión.- Bibliography.

Introduction

Hooray! We are a failed State!1 In 2010, I was involved in a project researching Development NGOS in Colombia. While waiting to interview an NGO director, I heard some of the staff cheering because Colombia had appeared on the Fragile States Index.2 They were celebrating that Colombia was on the Index as this would guarantee that the NGO could continue to seek funds at international level.3

This celebration encapsulates the story I want to tell about indicators and their use as a new kind of global dominance; it is a story of the little-known agency of the Third World in an era of indicator hegemony. In fact, indicators have more power in the daily life of the average Third World citizen than we can imagine. In many ways, this power is overlooked by the critical approach, which casts indicators as implausible neoliberal sim-plifications.4 This paper tells the story of how local, Third World stakeholders can be empowered by the indicator's dynamic.

Mainstream literature about indicators consists mainly of criticism of a new form of domination. This domination is unidirectional in its effect from North to South, planned instead of unexpected, related to neoliberalism and implies a new form of government.5 Furthermore, indicators are usually linked with multilateral financial institutions that reproduce quantitative mechanisms of governance as an imposition from the North on the South.6

As an academic from the South, I find this criticism produced in the North by the North, about people in the South, tedious. The new governance structuralism is tedious in the same way that paranoid structuralism is tedious:7 it assumes that the subject of domination is paralyzed, alienated or, in certain cases, stupid.

Instead of taking a paranoid view, I propose a "shift" of the North's perspective to analyse the domination scenario created by indicators. I will use another North Theory to talk about domination, an alternative theory that has to do with narratives, psychoanalysis, rhetoric, silences and minority resistance rather than the ever-predictable North domination. I am going to look at Doris Sommer's book, Proceed with Caution8 in which she explores a new way of analyzing north-minority relations, and use this analysis to propose an alternative perspective to deal with the phenomenon of indicators.

In that frame, the case study of the community mothers in Colombia serves me to show how this happen in a concrete space. My research question was directed to examine if we can assume that street level bureaucracy as community mothers can "resist" the hegemONIC domination of indicators when they deploy a strategic behaviour within this quantitative tools. In the case study, the community mothers use indicators, they gain benefits by using these tools and they understand their logic. I argue that resistance appear when community mothers achieve a substantial change between the policies in the books and the policies in the action. Thus, the case study shows how the community mothers agency over indicators helps to understand how the results of the policy in action appears in the daily context, and how the indicators intervene in the production of this unexpected results.

To that extend, this paper is divided into four sections. The first section offered a brief theoretical framework divided in two parts: a description of Sommer's approach to the otherness as a way to use a frame for the agency and resistance of the third world (i), and an explanation about the concepts of the third wave in the indicators literature as the frame of analysis proposed by this paper (ii). The second section provides a brief methodological context also in two parts: the arrival of the feminist accounting project as an approach to analyzing the regulation of domestic work in Colombia (i) and its unexpected links with the Community Mothers case study (ii). The third section read the field work results from the analytical frame proposed in section one. The last section offers some conclusions.

I. Theoretical framework

A. The Instrumentalized Minority or the Sommer's argument

After analyzing pieces of Latin American literature, Sommer claims that minority writers sometimes lead readers astray intentionally. This action presupposes a specific dominant attitude of the readers, who usually assume that they have the knowledge, the background and the intellectual skills to make sense of the narratives others. For Sommer, this operation involves a complex game of domination.9

In a sense, the orientalist attitude or the beliefs that make the readers think that they can understand otherness because they have, in some way, produced it, hide the instrumental action of the other. The story of otherness as the subject of domination systematically under-considers the other's agency. Indeed, the underlying theory always assumes that we cannot speak about this as a structural problem.10 But, what if the other led the North to produce it? What if the silence is a form of resistance? What if the global South "wins" as a result of these discourses relating to otherness?

Sommer explains that the problem of the arrogant Northern readers is that they assume "a cultural continuity between the writer and the reader".11 The entire book is an argument about how readers must be careful when making this reflection, and how they have to avoid being overconfident in terms of their own knowledge and understanding of the other's culture. The core of Sommer's argument is that the reader must proceed with caution so as not to reduce "otherness to sameness".

However, the book is also about how influential people such as Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas-Llosa, Rigoberta Menchú and Gloria Estefan, use the North's confidence in its knowledge as a strategy of resistance. It mocks the readers' intellectual overconfidence and reproduces, in jest, their own irrational desires about the other. In this respect, the South's response to domination is also one of resistance. For example, the paradox of Orientalism is that the West conceives the East as an exotic, mystical, magical and under-developed subject.12 13 In a pragmatic sense, however, the West loses something when it produces the other with its own paradigms; it loses the specific knowledge about how the other lives and how it talks about itself. The other always has the advantage of being continually constructed, under-documented, and not fully understood. The other is the subject of progressive production, it is a meaning produced by a continuous struggle.14

Despite the fact that Sommer is talking about literature, this kind of analysis is closely related to indicators as a new mechanism of Third World determination. Beyond this common criticism, I assess how local stakeholders use indicators as political spaces and tools to change power relations in particular fields. The use of indicators by Third World local stakeholders has the same agency and effect as Menchú's instrumental use of the exotic performance; they know what the North's object of desire is, and they simply act as such in order to take advantage of it. This dual use of the indicators technique, between the multilateral level and the local street-level bureaucrats, can also be read in the frame of Adler's Communities of Practice approach.15

This shift in the emphasis used to analyze indicators is interesting because it breaks with the rational dynamic as a discourse that is embedded in the indicators' own language. Instead, the proposed reading tells a story about irrationality and uncertainty. In fact, the people who produce indicator information in the global South (or the data from which indicators are constructed in a top-down power dynamic) are often conscious of what they have to say to transnational organizations and how it is useful for them to project these numbers as simpliications of reality. The global south "enjoys" and "wins", in many senses, through these quantitative governance mechanisms.

To that extent, this paper uses the arrival of the Feminist Accounting Project and the Community Mothers experiences in Colombia as a case study that shows how indicator mechanisms have been instrumentalized by grassroots and class-based social movements in the global South. The project journey tells the true story of how indicators have undergone a process of appropriation and strategic transformation from global mechanisms of governance to local opportunities for change, in a complex exercise of translation.

B. Indicators as Resistance? The Third Wave in the Indicators Literature

As I mentioned in the introduction, this work is conflicting with the mainstream criticism regarding indicators, in an attempt to advance into an arena of post criticism. Literature about indicators has been developed in two —clearly differentiable— points in time.16 Whereas, at first, the neoliberal approach applauded the appearance of ranking and other quantitative systems as effective means of imposing normative frameworks of different realities and propel development, criticism of indicators stated that they oversimplified reality. It, therefore, created Postcolonial dominations, in which the global North imposed governance and control mechanisms on the South through the legitimate and numerically verifiable accusation that countries in the south were unfavourably placed within the World ranking system, which organizes the capacity of nation states to reach certain goals.

In contrast to this first version of the criticism, the aim of this work is to inaugurate a third wave of literature on indicators. Moving away from Postcolonial criticism, which considers that indicators are tools exclusive to the global North, and definitively abandoning the neoliberal praise of indicators, the purpose of this work is to evidence how the reception of indicators in the global south is much more complex than what had been foreseen by the two previous snap shots.

This alternative version of the indicators criticism includes a number of characteristics. First, it evaluates the experiences of the global South from the perspective of the global South and with actors from the global South.17 18 Second, it destabilizes the main lines of literature. It does not believe that the use of indicators is good, but it also does not feel comfortable stating that the indicators are completely bad. On the contrary, it shows how the use of indicators has unpredicted effects on the literature, and that they are related to concrete actors in the global South who do not perceive the indicators as mere tools of domination. In contrast, actors in the global south also experience the indicators as tools and use them in political scenarios. A noteworthy example of this type of exercise is the work of Professor René Uruena on the local construction of the indicators of forced displacement.19

Third, this new understanding of the indicators aims to show how they are used as an alternative power mechanism. Indicators are used when power mechanisms do not work, either because the scenario itself excludes them or because the scenario in which they operate is unregulated.20

Fourth, the indicators are not mere normative sources that transmit ideal functioning models; they also operate in the normative field hiding local conflicts while perpetuating an idealized image. His point will be further developed in this work, where the social policy indicators hide the conflict existing between mothers and children in the scenario of the Community Welfare Homes, and serve to perpetuate the normative image of harmony between mother and child.

In this sense, the central problem that this paper seeks to solve is related to this shift. The critical theory on indicators concentrates on revealing their role as a mechanism for global governance and North-South domination. The Community Mothers case study shows how actors in the global south "use" and "instrumentalize" the indicators to obtain benefits. This shows that the domination is not unidirectional and that there are complex dynamics that include the agency of the marginalized population.

In this text, I seek to develop a central argument that indicators, as mechanisms of governance, are tools that are used by both the global North, to produce normative discourses relating to what is being measured; and, by the global South, as tools pertaining to resource distribution, resistance and agency. The latter is an unexpected effect of the indicators, which, as technical tools, were meant to be used only by certain actors. Contrary to this common sense idea of the way in which quantitative governance works in the global World, indicators are used by agents in the global South to alter power relations in certain arenas.

Actors in the global South may consider indicators as tools they can use in their negotiations for resources (funds, symbolic and financial capital). Thus, they can be used for ends that are different to those predicted in the global governance projects, where indicators are a mere strategy used to achieve development goals.

In this sense and from a theoretical point of view, the indicators constitute unexpected spaces of political action. For example, the measurement of care work related to the consolidation of early childhood is used by the community mothers as an instrument to obtain resources for the community homes in order to alleviate the lives of other women in their communities (caring for their children while other women access the labour market). This is important because public policies for child care do not seek to attend to the mothers' needs, but their children's. The difference of the public policy as "it is written" and "in action" is an example of the agency of the marginalized actors. This hypothesis is going to be developed in the last part of this article.

This has a direct effect on our knowledge of quantitative and neoliberal common sense, which implies an alteration in the way we imagine the data production dynamics. While the global North imagines a quantitative logic that involves lineal, causal and rational indicators, the reality of information gathering in local spaces speaks of chaos, irrationality and disintegration.21 22 Within the framework of neoliberal common sense, data reporting hides the agency that the actors in the global south exercise when it comes to producing information. Case studies such as the Community Mothers one reveal this reality.

This implies that, until now, it had been thought that indicators were a tool of governance displayed by the global North to give rise to normative discourses to discipline the Third World. Now, with this contribution, we must consider that indicators create scenarios of political action in which subordinate Third World actors win or are, at least, able to resist.

II. The Daily Experience of the Indicators: local space, global life23

This section presents a case study developed in Bogotá between June 2012 and February 2013 comprising a total of 31.5 hours of observation of daily work in Hogares Comunitarios de Bienestar (Community Welfare Homes or CWHs), 18 semi-structured interviews with people related to the social program, 3 focus groups with community mothers and documentary analysis of 8 different kinds of documents related to the operation of the CWHs.24 The research took place in the locality of San Cristóbal Sur, in Bogotá D.C., and with the Community Mothers involved with the fami version of the CWH program in El Espinal, Tolima, and the bambi program, in El Darién, Valle de Cauca.

The case study analyzes the situation of community mothers and the CWH system. Community Mothers are street-level bureaucrats25 who work for the CWHs, which are, in turn, run by the Colombian Family Welfare Institute (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar, ICBF). This system is responsible for assigning resources to two specific groups: children and women belonging to the two poorest income strata (strata 1 and 2 of the State Benefit System, or Sistema de Identificación de Potenciales Beneficiarios de Programas Sociales, SISBEN).26 The program has been running for more than 20 years and was restructured most recently in 2007, following the recommendations of Conpes Social 10927 published in December 2007, which developed a new early childhood policy, Colombia por la primera infancia. This new policy sought to eliminate the use of Community Mothers as a childcare system.

The arguments of experts against the CWH program were that Community Mothers are not childcare professionals and cannot guarantee the best education and nutrition conditions.28 Also, the evaluation of the social policy argues that the program is heterogeneous and that the welfare structure allows bureaucratic discretion without controls.29

This reform has led to political protests from Community Mothers30 who claim that they have worked for the State for more than 26 years without fair compensation.31 They also point out that Community Mothers are community leaders who help other women enter the labour market: "They measured the impact of the program on children, but never on working women."32

The case study proposed the following questions: How the indicators can be perceived as political spaces? How actors in the global south can deploy their agendas through indicators? Latin American welfare programs are being redesigned to include indicators as a way of measuring how they promote development.33 These trends challenge the understanding of legal accountability and basic rule-of-law issues such as the choice between rules, standards, and indicators as a way of assessing the results of public action in a new public management mode of public administration.

In this context, I wish to go beyond the argument that the domestic indicators of a social policy are not meaningful measures of reality.34 Furthermore, I would like to present this case study as evidence that shows how indicators are instrumentalized by local stakeholders in the global South, who take advantage of the idea that —in the global arena— indicators are meaningful measures of reality.

The case study also draws out the similarities and the differences between the global Feminist Accounting Project and how its claims are mobilized at local level by social organizations and by the state, empowering specific local stakeholders. In this way, the case study also demonstrates how gender claims travel and change from global to domestic contexts. The analysis maps social and state actors at the domestic level as well as the networks mobilized at international level to provide evidence of the influence of particular human rights frameworks on the design of legal institutions at the domestic level. The case study speaks about the transformation of politics and law in the context of globalization, comparing how the discourse of indicators works in the North and how it changes after local instrumentalization.

In this context, the case study is also structured around the question of exchanges between domestic and international stakeholders. It analyzes local processes in which legal contents and social meanings move from global arenas to different local ones.35 Specifically, the study explores two aspects of the "global/local exchange." Firstly, what is to be gained and lost in the exchange of legal and social ideas when they are mobilized beyond the space of the nation-state? For example, in the case of the Community Mothers' appropriation of the Care Economy Act, the Feminist Accounting Project has gained a local dimension that re-signifies its objectives in terms of social mobilization. The local appropriation of the global goals, however, breaks the causal logic of the global discourse of indicators.

The second aspect examined is the transformation of political and legal agendas when they move between different contexts and how they shape local agendas for social and legal mobilization. Therefore, the discussion delves into the actual content of the exchange among domestic stakeholders in order to understand the conditions under which legal ideas leave global contexts and reach the local level, as well as the transformations of political and legal agendas.

A. The Arrival of the Feminist Accounting

Project: an approach to analyzing the regulation of domestic work in Colombia36

In August 2010, a draft law "regulating the inclusion of the care economy in the National Accounting System with the object of measuring the contribution of women to the economic and social development of the country" was introduced in Colombian Congress. The draft law, presented by the Liberal Party Senator Cecilia López, was intended to "demonstrate the silent contribution made by women to economic development and to recognize symbolically the undeniable value of the work of women in creating national wealth."37 The draft law boasts a number of achievements, including the fact that it has raised the status of women and of housework as a female activity in several ways. It also proposed establishing Household Satellite Accounts (HSAS) and implementing a method for measuring care activities by requiring the National Statistics office (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, DANE) to start applying a Time Use Survey (TUS) within a three-year period following the passage of the law.

HSAS are accounting systems that operate in parallel to the United Nations' Systems of National Accounts (UNSNAS), constituting an alternative approach to the orthodox measurement mechanism adopted by the United Nations (UN) in the 1993 sna.38 They are heterodox economic methodologies designed to enable the measurement of activities that the official national accounting scheme does not recognize as productive (in other words: that are not included in Gross Domestic Product, GDP). Similarly, the tus is an instrument designed by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)39 to calculate the time and energy spent by women on household activities. It raises the possibility of cross-referencing variables to illustrate the negative effects of the incommensurability of domestic work. tus data is generally used to illustrate the correlations that exist between the absence of free time and poverty, domesticity and violence, and an absence of State protection and the household economy.40

The draft law, however, does no more than repeat an old feminist claim. After the important contribution of the North American economist Margaret Reid in highlighting the concern about the exclusion of domestic production in the national income accounts41 and those of New Zealander Marilyn Waring in challenging the UNSNA,42 the importance of recognizing unremu-nerated female labour was accepted in the CEDAW —suggesting a work measurement and its inclusion in the UNSNA— and, in 1995, in the Declaration of the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing.43 Lourdes Beneria, who is a former president of the

International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) and Professor Emerita at Cornell University, called the academic and political mobilization against the statistical bias that underestimates the force of women's labour, the "Accounting for Women's Work Project" or "The Accounting Project."44

Since the advances of the 1995 Beijing Conference, the project has achieved important victories. As a result of the initial Nairobi Conference recommendation, the United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (un-instraw), and the Statistics Division of the un have promoted the revision of national accounts and other statistical information on women's work. This initiative produced the measure of the Household Satellite Accounts (HSAS) mentioned above. Also, in 2008, the Sarkozy Commission or Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress —made up of Amartya Sen, Joseph Stiglitz and Jean-Paul Fitoussi— began a process of reflecting on the limits of GDP as an indicator of economic performance and social progress. Their final report —with worldwide recognition— was published in September 2009, promoting the previous Beijing recommendations.45 Then, in June 2011, the General Conference of the International Labour Organization (ILO) produced the c189 Domestic Workers Convention.46 This last international legal instrument was accompanied by a massive mobilization known as the "12 by 12 campaign," which promoted international networking in support of the ratification of the c189 in different countries.47

Additionally, thousands of friendly voices may be heard in the virtual world of the Internet, suggesting that a widespread activist movement has sprung up around the impact of orthodox GDP calculations. In general terms, mainstream criticism of the way GDP is measured is based on the theories of Gary Becker, on the contribution of everyday activities to wealth creation;48 and those of Joseph Stiglitz, on the generation of non-monetary resources in households.49 In a similar vein, there are several feminist projects that promote alternative (or domestic) measures of GDP. All of these are in some way linked to a movement labelled Gender and National Accounts in Latin America. Most of the relevant information has been produced by the cases of France, Spain and Mexico, all of which have accounts that are compiled at province or department level.

The framing of the debate has important regional characteristics and will appear as a cascade reform if the mobilization sustains current patterns.50 For example, in terms of the c189 ratification process, the 2012 mobilization has enjoyed success at regional level: Uruguay ratified the Convention in May 2012; Peru recently announced a commitment from the Congress' Work Commission to address the need to enforce the Convention; in Paraguay, the Ministry of Justice and Work (MJT) has proposed a series of adjustments to be considered within the legislation in order to grant signiicant protection to domestic workers; and, Colombia organized the first Domestic Workers Congress on March 30, 2010, and founded the Latin American and Caribbean Confederation of Domestic Workers (Confederación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Trabajadoras del Hogar, coNLACTRAHo). Since then, March 30th celebrates the Domestic Workers' Day of Latin America.

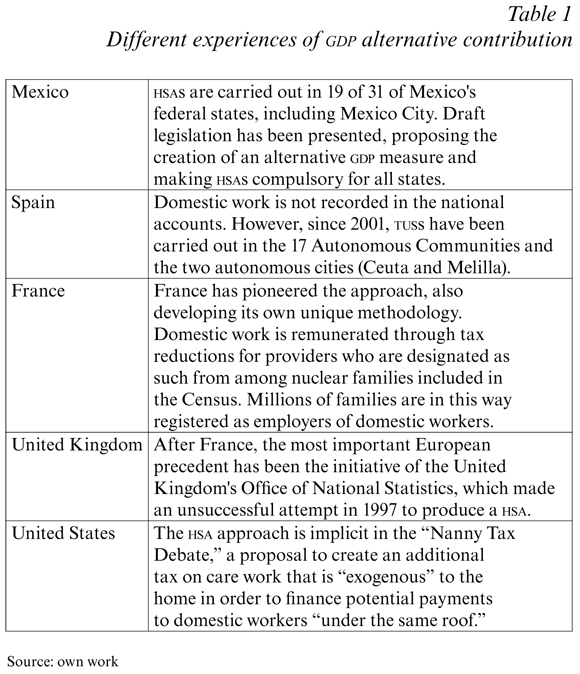

Additionally, the Accounting Project shows specific outcomes in terms of challenging the UNSNA. Some budgets already take domestic work into account and calculate its contribution to GDP in a process that is parallel to oficial reporting. The different experiences in this field may be summarized as follows:

The Colombian draft law, the Care Economy Act, reproduces the Mexican model exactly. It proposes a staged implementation. The first stage would entail the immediate establishment of a hsa budgetary mechanism designed to assign value to unpaid domestic work. Subsequently, an incremental process would be initiated to establish regular calculation of an integrated, or household GDP that would reflect unremunerated productive work; that is, reproductive or caring activities.51

Based on a case study of the Colombian Care Economy Act, this paper analyzes how domestic work claims change as they move from international to domestic contexts.52 To that extent, the case study speaks about the transformation of politics and law in the context of globalization, highlighting how domestic frameworks transform and affect the international goals of the domestic workers mobilization movement.

B. Colombia after the Care Economy Act

Three years after the promulgation of the Care Economy Act, nothing has changed in Colombia.53 The law has not been implemented and the National Statistics office (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, DANE) has not made any progress in applying a Time Use Survey (TUS) to measure care activities. Unfortunately, there are virtually no voices to make the law accountable.54

In the opinion of some gender experts, the reform promoted by this draft law will prove to be useless.55 The objective of the project then, is purely symbolic and its scope is nothing more than to measure, differentiate, include and demonstrate, and not to pay. In Colombia, the Accounting Project does not fit into a leftist framework in which the unions embrace the legal change in order to transform the daily life of domestic workers.56 Instead, this legal change has been seen as a proposal to provide legitimacy to one of the traditional parties in the Colombian political spectrum: the Liberal Party. Other arguments have also suggested that the recognition of domestic work through a simple process of accounting parallel to the national accounts will have negative consequences for women who are currently carrying out this kind of activity and who wish to enter the labour market. The current reform, though well intentioned, will in fact generate incentives for women to remain outside the market, since it naturalizes, normalizes and legitimizes the existing link between women and care work.57

The counter-hegemONIC discourse of the GDP, however, has had some unexpected effects. The movement of Community Mothers, who are care workers paid by the state and community organizations, has adopted the "care work as productive work" discourse as its banner. In fact, these women have mobilized their symbolic significance as Community Mothers with the legal legitimation afforded to them by the Care Economy Act.

C. The Community Mothers' Speech in Doris Sommer's Script

The effects of the Feminist Accounting Project come to light in daily conversations with the Community Mothers. They explain their precarious status as public servants in terms of the hidden value of care work. They also use the care work discourse to secure funding for their organizations: "We need economic cooperation because the state rejects us. The ICBF don't provide what we need in order to take care of the children. For these reasons we have to seek funding with the NGOS and non-profit organizations that understand the situation of care workers in a country like Colombia."58

But they are also involved in the production of statistics and data that is related to the women's Time Use Survey. When asked for the way in which they report information to the ICBF, they respond: "The numbers lie, they always lie. You want the numbers to say that we are satisfied? The numbers are going to say that. Nobody reports what actually happens in the ICBF forms. It is clear that the data has to satisfy the ICBF in order to get more funds, so we are going to say what the institution wants to hear. We have data for everything, for funding oriented toward empowering female stakeholders and for funding oriented toward not empowering women."59

This evidence shows how the daily life of the indicators rhetoric is challenged by the daily life of the people in the Third World that produce the data. While mainstream literature on indicators claims that it is a new technocratic discourse that reinforces North-south domination, everyday life at local level is not affected by this domination. Pragmatically, people know exactly what the indicators are for and why they are useful: to obtain funding. Thus, the Community Mothers perceive the indicators as a governance mechanism that seeks a certain representation of the local identity. They know that the North and international cooperation entities will pay in order to have their desires satisfied; they are going to give money to people who can perform the role of empowering women in the South, especially violated women in the South and explOITed care workers in the South. These women, in turn, can produce this identity as a fake front, simply in order to secure resources.

In fact, internal ICBF reports show how international cooperation funds 64 per cent of the total operational cost of the CWH program in Colombia.60 The people involved with the CWHs have always recognized labour funding as a key activity of their daily work. In one interview, a Community Mother in El Darién, Valle del Cauca, said: "The ICBF do not provide us with anything. We only have the Swiss cooperation to work with. Thank God, the Gonnergemeinschaft Foundation supports us and our children."61

Interaction across the language of indicators happens between local organizations in the South and NGOS in the North. The ICBF, as a public organization, only mediates this interaction "with the goal of materializing international cooperation in local spaces."62 The Community Mothers associations are always familiar with fundraising. For example, one leading Community Mother told me: "Gender issues are now in fashion throughout the whole world, so working with women pays, and pays well. You only have to be patient and look in the right places. There is a lot of help for us, but the problem is that we are not well organized and we do not have information about all the sources, so we fight among ourselves for the same resources. The ICBF has also failed in terms of disseminating information."63

The local actors have learnt how the gender discourse works in the development agenda and have instrumentalized the goals of the North in order to obtain funds. There is no unidirectional domination in the issue of development; the South always knows its role in the game and plays within the framework of those rules. The appropriation of the "care work discourse" can be read as a strategic local action to generate dialogues with the North. For example, one community leader told me: "Now we have this issue about the domestic workers. Here we have exploitation and human rights violations. Do you know why we don't have a fair wage? Easy, it's because we are women."64 The local players have appropriated the feminist argument in order to position their local needs within a global agenda. While in the linear perspective to read the effects of the law, the Care Economy Act is inefficient, the law produces these kinds of unexpected changes in reality. To effect this transaction, they know that they have to work with the language of indicators, and they have to work with it as a tool. As the same community leader quoted above said: "You have to work with numbers, you have to learn how. Now the numbers are our food source."65

At the same time, they do not want to lie in the reports and they think that the system for communicating information about their work is far from ideal. "I don't want to lie, but my case doesn't fit within the information request. I am not an activist —we are public functionaries— but the State does not recognize us. What can we do? We have to play with the spaces that we are required to fill in."66

Another important issue is that the dynamic that "produces" the data is far removed from the place where the logical voice of the indicators is heard. While the mechanisms are presented as linear and direct, the daily life of the person that produces the data is dominated by other kinds of tendencies: chaos, irrationality and disconnection. One Community Mother said: "You always assume that what happened is what is reported, or that you can reproduce reality in a mandatory form that the mothers should fill in every month. That never happens. We always fill in the blanks thinking about the supervisor's opinion of our work but never use the forms as an accurate picture of what happens with the children (...) We are always in a rush with the ICBF asking us to fill in the forms; that is the reality of this work."67

In fact, the indicators do not depict reality on a 1:1 scale. There is always a degree of indétermination and interpretation stemming from the agency of discretion of the actors in charge of producing the data that the indicators seek to capture. These actors, tend not to be neutral abstract players but, rather, people with political agendas and ideological claims.

This means that, while the Weberian model is the façade of public administration in Colombia, on a day-to-day basis, public processes function under different dynamics. The welfare state has a complex connection with the rule of law, because the welfare programs and the social policy represent a model of "low-density rule of law" as a type of a rule-of-law regime. This means that in the spaces where social programs operate, the street-level bureaucrats haggle over legal issues in order to institutionalize the welfare state.

Thus, the case of the Community Mothers is an example of local appropriation of the Feminist Accounting Project discourse. The Community Mothers use the Economy Care Act rhetoric in order to legitimize their own expectations in the local debate: "The State has to recognize our work because care work is a form of discrimination. The ICBF always think that we do nothing because we just care for children. Well, they may have been able to think like that in the past, but now they are obliged by law to take women's work into account. They have to pay us a fair wage, they have to recognize that we have labour rights, and they have to compensate us for all the injustice with money."68

The transnational arguments of the Feminist Accounting Project have shifted into a local context. As the law has indeterminate effects, its results are not linear, and we cannot measure the impact or the enforcement of the Economy Care Act using causal or positivist logic. Instead, we can document how the meanings of the law move and are used by uncoerced players, producing unexpected results. The discourse of the alternative GDP as a counter-hegemONIC narrative against the white, male

North has generated an unexpected result: the implementation of their logic has not produced what the Care Economy Act proposed, which is a new measure of female care work. Instead, the law has empowered Community Mothers to demand their labour rights from the State, and mobilize the care work idea as a political claim and a form of resistance.

But this non-linear effect is not the only lesson that the case study offers. The Community Mothers, as street-level bureaucrats, are stakeholders who instrumentalize the logic of indicators. As Sommer told us, the indicators dynamic shows how the North has produced a global governance technique that has betrayed it. The local players just take advantage of the North's confidence in its own knowledge and use the tools that it created to resist. Community Mothers are an example of how local stakeholders have manipulated data and intentionally falsified the information that the indicators report. This can be interpreted as a way in which the global south uses indicators as a form of resistance.

While it would be easy for mainstream legal liberal studies to label the Community Mothers case as an example of corruption, rent seeking and bad governance in Latin America, I think that the evidence also tells a story where the linear logic of corruption versus good practice does not work. The actions of Community Mothers, their empowerment and their strategic use of the indicators could reinforce the image of the South as a failed State because it is corrupt and arbitrary in the application of legal mechanisms, but it can also help in the construction of a new paradigm, where the local actors play a key distribution role in peripheral spaces. This represents a new approach to global governance in local spaces in the South.

III. Bad Mothers: mothers and their children in social policy indicators

The purpose of this section is to reveal the mothers' agency in showing their political aims that are in opposition to the agenda of the national government. This opposition is important because to speak of the tension between mother and child reveals another way in which indicators play a role in building the reality of the global South. While mothers use a quantitative logic to obtain more funds, the indicators give rise to a reality that hides the conflict between mothers and children. In this sense, the indicator creates a political space of combat. While it creates a false reality that allows the mothers to benefit from certain chains of funds, it also creates a collective imagination that links mothers as mere instruments of their children's wellbeing.

Inside this script we can said: Children or their mothers, one or the other. Despite the fact that we are culturally not accustomed to considering mother and child as opposing subjects, this seems to be one of the classical dilemmas of social policy. After all, the old question posed by socialist feminism in relation to who should be responsible for children —their mothers or the State— continues to be valid for assessing many of the normative arrangements which, together with the seal of social policy, reproduce disadvantageous situations for women69 70.

Up to this point, we have seen how indicators appear in the daily life of women and how they use the technical language to raise funds. Readers who have not yet been persuaded, will be thinking that this is a simple case of corruption or that, perhaps, the word resistance that I use in the title of this article is an overly generous framework for the actions undertaken by Community Mothers.

It is precisely within this tension that the mothers' agenda in the face of the governance of the indicators becomes more acute. In their discourse, the Community Mothers use indicators that help them to obtain funds, not only to "obtain funds". The CWH program has, for a long time, been at risk of being closed by State agencies. The funds allow the Mothers to maintain this program that helps other women and not their children: "this is a good program. If I look after this child... even if I don't look after him correctly, his mother can go to work and bring in money; she will feel better about herself and will have a better relationship with her husband. This mother has also been my friend for the past 11 years, for the past 3, or 5. It is clear to me that I am not working for the children. The indicators are right. The children are not well cared for here. But the indicators should measure how much we help other women. But, of course, that wouldn't be an indicator because no one cares about what goes on with women. This is why I work for women."71

The above testimony reveals the way in which indicators participate in the political scenario of resistance. The indicators measure an objective that hides how the program really works. While measurements of the CWH constantly reproduce results in terms of the lives of the children, the program works to improve the lives of women. In the Community Mothers' narratives, the indicators do not measure the benefits of the program as a policy of conciliation between productive and reproductive work because women are not a political priority for the government. Early childhood is. And it is clear that between women and children, it is politically correct to help the latter. So much so that we believe that if we help the mothers, we are also helping children. This supposes that mothers and their children are complementary, indissoluble subjects. Or, at least, this is the normative image of the subjects that the indicators have helped to build.

Very often, the law has reinvented the mechanisms that produce what is considered feminine as something that is second class, dependent, secondary, something minor. As already affirmed by Mary Joe Frug, maternalization is one such element. To maternalize is to think of the feminine as essentially linked to the reproductive, in this way naturalizing the mother-child bond as a central pairing within contemporary legal production.72 Civil rights, family rights, labour rights, penal rights and rules of succession are some of the norms that help to normalize the imposed "natural" bond between mothers and their children.

The mother-child bond can also be traced back to a number of social programs undertaken as part of a government strategy to fight poverty. More Families in Action and Community Welfare Homes (CWH) are only two of them.73 These programs regulate the lives of mothers and their children, unifying them as a single beneficiary. In many ways, we continue to think that by helping children we also help their mothers and vice-versa. This implies that the benefits for early childhood are channeled through changing the lives of the mothers (with a greater number of bureaucratic conditions to fulfill, for example) or money is given to mothers for them to spend on their children. As exposed by the government in response to the consolidation of conditional subsidies in the case of the More Families in Action program, to give money to the mothers is good because it has been proven that it is they —and not the children— who invest more in the home: mothers spend more on food, on health, education and diversion for the members of the family.74

However, the fieldwork undertaken in the CWH obliges me to insist on an old feminist warning: mothers and their children are not the same, nor does one win when the other wins. On the contrary, improving the children's situation, very often implies irrevocably worsening the lives of their mothers. This also works the other way around: improving the lives of the mothers can sometimes worsen the condition of their children. Thus, precisely because mothers and children are not the same —nor should they be seen as indissoluble subjects— the law acts and indicators measurements to the detriment of women when it produces them as mere mothers or treats them as if they were wandering uteruses or two-legged matryoshkas with no life plan of their own.

The reality of the CWH program points out that, despite being a questionable program in terms of its impact on early childhood,75 it is a social policy that helps low-income women to enter the labour market and it has proven its success as a means of conciliation between productive and reproductive work.76 However, the indicators given in the results of the CWH program reveal that children do not improve their weight, height, social skills or cognitive development during their stays in the community homes.

Despite this, while the program's impact assessments reveal that its results are questionable in terms of the health, education and psychosocial skills of the beneficiaries, the qualitative work with the mothers reveals that the program develops favourable policies for women. Thus, there is a deep tension between the social policy that is "written in books" and social policy "in action", exercised by the Community Mothers.

It is not only the Community Mothers that are a positive example of local female leadership. The program also helps, as I pointed out above, women who are mothers of the children being looked after, as this allows them to effectively access better paid jobs, increase their level of income, and to positively change their stance for negotiation in the home. At the same time, being part of the labour market increases their feelings of wellbeing and their quality of life77. These are the result that the policy "in action" produced and the indicator hide.

The following is very clear for the Community Mothers: "Why don't they measure our work? Because the people from the ICBF, who criticize us, don't come here to see that what we do is help other mums, because caring for children costs money, because this takes opportunities away from them. Why do they only come here to measure and weigh the children? I'll tell you why, because us women are less important than our children."78

It is clear for the Community Mothers that what happens when prevalence is given to the indicators relating to early childhood wellbeing in the face of care work —developed, among other things— by the Feminist Accounting Project, indicates a political preference against women. It is clear to them that to measure the children's wellbeing is politically better than measuring the impact that caring for the children has on the lives of the women. It is clear to them that a bad result in terms of the care that is provided for the children supports political decisions that question the program, that their budget is likely to be reduced, or that someone is likely to propose that the program should be closed down.

However, they are also clear on why nothing happens when the State does not fulfill its obligation to measure the women's care work. In this sense, the indicators build a soft government that stabilizes normative social images and neutralized political decisions. No one knows that this scenario of conflict hides behind bad results in terms of child development derived from the assessment of the impacts of the CWH program. This is the indicators magic. Indicators language has the power to hide the conflictive reality between mother and children and at the same time create the reality that is being measured, in which there is no conflict between those subjects and the results over children are most important that the results over women. The political election inside this debate is totally invisible. It is invisible behind the powerful presence of the results number produced by the children care logic and the legitimation effects that the objectivity of the numbers and the indicators language has. This is the way in which the indicators spaces are extremely political.

Conclusion

This work is an attempt to develop a post critical scenario in the literature on indicators. In response to the liberal position —that applauds the quantitative method as an efficient way to simplify reality— and of Postcolonial criticism —that identifies, in the indicators, a new manifestation of geopolitical power asymmetry— the purpose of this work was to shed light on the deep complexity present in the implementation of indicators.

Using the Community Mothers case study and the arrival of the Feminist Accounting Project in Colombia, the purpose of this paper was to reveal at least two elements regarding how indicators work. The first is related to the instrumental use of quantitative language. Beyond that which is predicted by the neoliberal version or Postcolonial criticism, people in the global south have been able to appropriate the language of the indicators and use it to develop their own political agendas. The Community Mothers are an example of how this happens. They use the indicators to raise funds because they are deeply convinced that their work helps other women. This operates as a resistance because it opposes the government agenda, which considers that its work is dedicated to early childhood or to helping children.

Second, the indictors appear as the political scenario in the case of the Community Mothers in a number of ways. They produce a normative reality that hides the conflict and reifies the mother-child bond, but it also builds a type of government that implements normative images that they themselves produce. This is what happens with social policy and the indicators of the CWH program. The indicators are used when traditional mechanisms are insufficient or excluded from the possibility of intervention.

I hope that these findings, thus, serve to trace a research agenda on indicators in the global South that goes beyond common ground in discussion about governance techniques. I also hope that this work is evocative for socialist feminists who find the greatest of inequalities to be women's reproductive work. Both the Feminist Accounting Project and the workings of the CWH developed in this study could constitute good objects of analysis in this debate.

Foot Note

1Lina Buchely, Fieldwork diary, March 23th, 2010 (2013).

2Fragile States Index: http://ffp.statesindex.org/

3Lina Buchely, The Naoisation Dilemma: International Cooperation, Grassroots Relations and Government Action from an Accountability Perspective: A Case Study of Colombian Migration naos and the National System of Migration, 31 Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal, 63-117 (2013). Previous version available at: http://works.bepress.eom/lina_buchely/2/

4Kevin E. Davis, Benedict Kingsbury & Sally Engle Merry, Indicators as a Technology of Global Governance, 46 Law and Society Review, 1, 71-104 (2012).

5Sally Engle Merry, Measuring the World: Indicators, Human Rights and Global Governance, 52 Current Anthropology, Supplement 3, S83-S95 (2011). Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/full/10.1086/657241

6Tor Krever, Quantifying Law: Legal Indicator Projects and the Reproduction of Neoliberal Common Sense, 34 Third World Quarterly, 1, 131-150 (2013). Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2196988

7Duncan Kennedy, A Critique of Adjudication [fin de siècle] (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1997).

8Doris Sommer, Proceed with Caution, When Engaged by Minority Writing in the Americas (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999).

9Doris Sommer, Proceed with Caution, When Engaged by Minority Writing in the Americas (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999).

10Gayatri Chacravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999).

11Doris Sommer, Proceed with Caution, When Engaged by Minority Writing in the Americas (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999).

12Arturo Escobar, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World (Princeton University Press, Princeton 1995).

13Edward W. Said, Orientalismo (Random House Mondadori, Barcelona, 2004).

14Doris Sommer, Proceed with Caution, When Engaged by Minority Writing in the Americas (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999).

15Emanuel Adler, The Spread of Security Communities: Communities of Practice, Self-Restraint, and NATO's Post-Cold War Transformation, 14 European Journal of International Relation, 2, 195-230 (2008).

16Kevin E. Davis, Angelina Fisher, Benedict Kingsbury & Sally Engle Merry, eds., Governance by Indicators: Global Power through Data (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012).

17Marcela Abadía, Criminal Justice Policy through the Use of Indicators: The Case ofSexual Violence in the Armed Conflict in Colombia, 25 International Law, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, xxx-xxx (2014). Available at: http://www.javeriana.edu.co/Facultades/C_Juridicas/pub_rev/int.htm

18Lina María Céspedes-Báez, Far beyond What is Measured: Governance Feminism and Indicators in Colombia, 25 International Law, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, xxx-xxx (2014). Available at: http://www.javeriana.edu.co/Facultades/C_Juridicas/pub_rev/int.htm

19René Urueña, Internally Displaced Population in Colombia. A Case Study on the Domestic Aspects of Indicators as Technologies of Global Governance, in Governance by Indicators: Global Power through Quantification and Rankings, 249-280 (Kevin E. Davis, Angelina Fisher, Benedict Kingsbury & Sally Engle Merry, eds., Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012). Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2282812

20Marcela Abadía, Criminal Justice Policy through the Use of Indicators: The Case of Sexual Violence in the Armed Conflict in Colombia, 25 International Law, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, xxx-xxx (2014). Available at: http://www.javeriana.edu.co/Facultades/C_Juridicas/pub_rev/int.htm

21Akhil Gupta & Aradhana Sharma, Globalization and Postcolonial States, 47 Current Anthropology, 2, 277-307 (2006).

22Michael Lipsky, Street-level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services (Russell Sage Foundation, New York, 2010).

23The tittle of this section is inspired by the oNGOing PhD dissertation of my friend Luis Eslava, Local Space, Global Life, The Everyday Operation of the International Law and Development (submitted in total fulfiLLMent of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Institute for International Law and the Humanities, IILAH, The University of Melbourne, 2012). Available at: https://kent.academia.edu/LuisEslava/Doctoral-Thesis

24These documents include bulletin boards, planners, attendance lists, minutes of food control, icBF information circulars, training brochures, ICBF requests for information to associations of Community Mothers and e-mails from the ICBF to community mothers.

25"Street-level bureaucrats" is a label first used by Michael Lipsky in 1980 to make a reference to the public servants that have a connection with the citizens in the daily operation of the public program. The beauty of the street level bureaucrats is that they have a precarious connection with the government of the center of power, while they are perceived as the state representation in the social arena. In the Lipsky version of the street level bureaucrats, they are important because they substantially change the meaning of the public policy in the implementation period, through the discretion exercise. Then, the public program is not what the policy maker in the center of power designs. The public policy is what the street level bureaucrats decide on a daily basis.

26In Colombia, the socioeconomic classification or division of the population is represented by strata, which group citizens according to their level of wealth. This classification influences the cost of public services and the designation of social policy benefits.

27The Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social (National Council for Economic and Social Policy, or CONPES) is chaired by the President of the Republic. It is responsible for preparing economic and social policy proposals. Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social, CONPES, Departamento Nacional de Planeación, DNP, Conpes Social 109, Política Pública Nacional de Primera Infancia, Colombia por la Primera Infancia, December 2007. Available at: http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/primerainfancia/1739/articles-177828_archivo_pdf_CONPES109.pdf

28Raquel Bernal, Camila Fernández, Carmen Elisa Flórez-Nieto, Alejandro Gaviria, Paul René Ocampo, Belén Samper & Fabio Sánchez, Evaluation of the Early ChildhoodProgram Hogares Comunitarios de Bienestar in Colombia (Centro de Estudios sobre Desarrollo Económico, cede, Universidad de los Andes, Working Paper Series, 2009-16, 2009). Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1486209

29Interview with Raquel Bernal, January 29, 2013.

30 http://www.eltiempo.com/justicia/ARTICULO-WEB-NEW_NOTA_INTERIOR-11734032.html; http://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/las-madres-comunitarias-no-van-acabar-ICBF/260164-3

31Focus group in Bogotá, Colombia. San Cristóbal Sur. October 17, 2012. For the evolution of the situation and the protest, http://www.eltiempo.com/vida-de-hoy/ARTICULO-WEB-NEW_NOTA_INTERIOR-13020864.html, http://www.elmundo.com/portal/noticias/poblacion/madres_del_ICBF_inconformes.php

32Focus group in El Espinal, Tolima. November 22, 2012.

33Kevin E. Davis, Angelina Fisher, Benedict Kingsbury & Sally Engle Merry, eds., Governance by Indicators: Global Power through Data (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012).

34Sally Engle Merry, Measuring the World: Indicators, Human Rights and Global Governance, 52 Current Anthropology, Supplement 3, S83-S95 (2011). Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/full/10.1086/657241

35Emanuel Adler, The Spread of Security Communities: Communities of Practice, Self-Restraint, and NATO's Post- Cold War Transformation, 14 European Journal of International Relation, 2, 195-230 (2008).

36The first version of this section was published in Lina Buchely, Economic Inclusion? A Landing of the Feminist Accounting Project: An Approach to Analyzing the Regulation of Domestic Work in Colombia, 1 Global Sciences & Technology Forum, GSTF, Journal of Law and Social Sciences, 2 (2012). Available at: http://works.bepress.eom/lina_buchely/3/

37Television interview with Senator Cecilia Lopez on City TV, July 28, 2009, explaining the reasons behind the proposed law. Available at: http://www.citytv.com.co/videos/17010/cecilia-lopez-propondria-proyecto-de-ley-sobre-la-economia-del-cuidado

38The sna, adopted in its original form by the un in 1968 (1968 sna), is the system employed by Colombia to measure its national accounts. It was revised in 1993 (as the System of National Accounts of the United Nations, or 1993 UNSNA). United Nations, United Nations' Systems of National Accounts, ljnsnas, 1993. Available at: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/sna1993.asp

39Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe, CEPAL, in Spanish.

40María Eugenia Villamizar García-Herreros, Uso y distribución de tiempo de mujeres y hombres, in Bogotá: Midiendo la desigualdad. Informe final de Consultoría (Alcaldía de Bogotá, eds., Subsecretaría de la Mujer, Género y Diversidad Sexual, Alcaldía de Bogotá, Gobierno de la Ciudad, Bogotá D.C., 2011).

41Margaret Reid, Economics of Household Production (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1934).

42Marilyn Waring, If Women Counted - A New Feminist Economics (Paperback, HarperCollins, New York, 1988).

43The Beijing Declaration states (art. 156): ".. .women contribute to development not only through remunerated work but also through a great deal of unremunerated work. On the one hand, women participate in the production of goods and services for the market and household consumption, in agriculture, food production or family enterprises. Though included in the United Nations System of National Accounts and therefore in international standards for labor statistics, this unremunerated work —particularly that related to agriculture— is often undervalued and under-recorded. On the other hand, women still also perform the great majority of unremunerated domestic work and community work such as caring for children and older persons, preparing food for the family, protecting the environment and providing voluntary assistance to vulnerable and disadvantaged individuals and groups. This work is often not measured in quantitative terms and is not valued in national accounts. Women's contribution to development is seriously underestimated and thus its social recognition is limited. The full visibility of the type, extent and distribution of this unremunerated work will also contribute to a better sharing of responsibilities." Declaration of the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, 1995. Available at: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/platform/

44Lourdes Benería, Gender, Development and Globalization: Economics as if all People Mattered (Routledge, London, 2003).

45The final report can be downloaded at: http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/documents/rapport_an-glais.pdf, http://www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr/en/index.htm

46For engaged voices, this convention is important because: "Countries that ratify c189 have to adopt laws that recognise the right of domestic workers to collectively defend their interests through trade unions. In addition, Convention c189 protects the right of domestic workers to a minimum wage in countries where such a wage exists; the Convention guarantees them a monthly payment and access to social security including in the case of maternity; and it gives them one day off per week and regulates their working hours and leave days. c189 recognises domestic work as any other work and ensures that domestic workers are treated as any other worker under labour legislation." See the International Trade Union Confederation News

47http://www.idwn.info/?q=node&page=5

48Gary Becker, A Treatise on the Family (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1991).

49Joseph Stiglitz & Bruce Greenwald, Towards a New Paradigm in Monetary Economics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003).

50In the article Re(gion)alizing Women's Human Rights in Latin America, Elisabeth Jay Friedman shifts the traditional focus of the domestic/international level to a regional/national dynamic in order to explain the process of establishing, adopting and implementing norms pertaining to woman's human rights related to the prevention of gender violence in Latin America. By using the concept of the Ping-Pong effort, the author explains how civil society organizations articulate regional legal standards to produce normative changes at the national level. The author uses the examples of Chile and Brazil to show the legal cascade configuration in the region, a cascade that has helped to nationalize some of the prescriptions of the Belém do Para Convention (1994) in terms of gender violence, moving these issues from the regional to the national level. Cascade means that the norms recognized in the Convention —as regional instruments— have been transplanted to the national legal system by means of a regional strategy that organizes the shift between the regional and the national level as a Ping-Pong dynamic. Indeed, the author suggests that the regional level could play a key role in terms of legal changes to national systems. Particularly, Friedman highlights the importance of two legal tools for creating hard law frames (binding norms) that help in the institutional and social struggle against gender violence: Human Rights discourse and Judicial activism. Regarding these points, the author states that "women's rights as human rights" is an especially successful formula in the region, used more in litigation in the Judicial branch, rather than in the Executive branch. However, the author implies that work by the judiciary is succeeded by work with the Executive and Legislative powers under left-wing governments (Michelle Bachelet in Chile and Luiz Inäcio Lula da Silva in Brazil) because leftist parties are traditionally allies of the feminist agenda in the region. Elisabeth Jay Friedman, Re(gion)alizing Women's Human Rights in Latin America, 5 Politics & Gender, 3, 349-375. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/1928222/Re_gion_alizing_Womens_Human_Rights_in_Latin_America

51 http://www.inegi.org.mx/inegi/contenidos/espanol/eventos/vigenero/dia28/panel3_mesas_pdf/Trabajo/Trabajo-ENUT-y-Trabajo-dom%C3%A9stico-no-remunerado.pdf

52Emanuel Adler, The Spread of Security Communities: Communities of Practice, Self-Restraint, and NATO's Post-Cold War Transformation, 14 European Journal of International Relation, 2, 195-230 (2008).

53Lina Buchely, Economic Inclusion? A Landing of the Feminist Accounting Project: An Approach to Analyzing the Regulation of Domestic Work in Colombia, 1 Global Sciences & Technology Forum, GSTF, Journal of Law and Social Sciences, 2 (2012). Available at: http://works.bepress.eom/lina_buchely/3/. Colombia, Ley 1413 de 2010, por medio de la cual se regula la inclusión de la economía del cuidado en el sistema de cuentas nacionales con el objeto de medir la contribución de la mujer al desarrollo económico y social del país y como herramienta fundamental para la definición e implementación de políticas públicas, 47.890 Diario Oficial, 11 de noviembre de 2010. Available at: http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/ley_1413_2010.html

54http://cecilialopez.com/

55Luz Gabriela Arango & Pascale Molinier, comps., El trabajo y la ética del cuidado (Editorial la Carreta Social, Bogotá, 2011).

56In most of the Pink tide Latin American countries, the "12 by 12 campaign" mobilization, mentioned above, is supported by the International Trade Union Confederation and networking of the national unionist movements, traditionally linked to the left of the political spectrum. By Pink Tide (Turn to the Left) Latin America, I wish to reference the current prevalence of leftist political parties in the region (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Nicaragua and Venezuela), which is currently labeled a Pink effect, in reference to the symbolic link between the left and red flags. This tide is basically characterized by political and economic opposition to the 1990 Neoliberal Washington Consensus measures.

57Lina Buchely, Economic Inclusion? A Landing of the Feminist Accounting Project: An Approach to Analyzing the Regulation of Domestic Work in Colombia, 1 Global Sciences & Technology Forum, GSTF, Journal of Law and Social Sciences, 2 (2012). Available at: http://works.bepress.com/lina_buchely/3/

58Focus Group. El Espinal, Tolima. November 22, 2013.

59Focus Group. El Espinal, Tolima. November 22, 2013.

60Interview with Camilo Andrés Hurtado, NGO worker involved with the implementation of Centros de Desarrollo Infantil, or Centers of Infant Development (CDI, for its acronym in Spanish) for the ICBF.

61Interview with Gladys Meneces, Leader of Hogar Bambi Darién. September 19, 2012.

62Interview with Rosa María Navarro, Ex-General Director of ICBF. November 2, 2012.

63Interview with Gladys Meneces, Leader of Hogar Bambi Darién. September 19, 2012.

64Focus group. El Espinal, Tolima. November 22, 2013.

65Focus group. El Espinal, Tolima. November 22, 2013.

66Focus group. El Espinal, Tolima. November 22, 2013.

67Focus group. Bogotá - Colombia. San Cristobal Sur Locality. October 17, 2012.

68 Focus group. Bogotá - Colombia. San Cristobal Sur Locality. October 17, 2012.

69Nancy Fraser, Fortunes of Feminism: From State-Managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis (Verso, London, New York, 2013).

70Tamar Pitch, Un derecho para dos: la construcción jurídica de género, sexo y sexualidad (Cristina García-Pascual, trad., Trotta, Madrid, 2003).

71 Focus group. Bogotá - Colombia. San Cristobal Sur locality. October 17, 2012.

72Mary Joe Frug, Un manifiesto jurídico feminista posmoderno, in Crítica jurídica, 223250 (Mauricio García-Villegas, Isabel Cristina Jaramillo-Sierra & Esteban Restrepo-Saldarriaga, eds., Universidad de los Andes y Universidad Nacional, Bogotá, 2006).

73In Colombia these programs are: Más Familias en Acción, http://www.dps.gov.co/Ingreso_Social/FamiliasenAccion.aspx y Hogares Comunitarios de Bienestar, http://www.ICBF.gov.co/portal/page/portal/PortalICBF/Servicios/PreguntasFrecuentesNew/Hogares

74Departamento Nacional de Planeación, DNP, Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Internacional, El camino recorrido, Diez años de Familias en Acción (Presidencia de la República, Bogotá, 2010). Available at: http://www.dps.gov.co/documentos/FA/EL%20CAMINO%20RECORRIDO%20WEB.pdf

75Raquel Bernal, Camila Fernández, Carmen Elisa Flórez-Nieto, Alejandro Gaviria, Paul René Ocampo, Belén Samper & Fabio Sánchez, Evaluation ofthe Early Childhood Program Hogares Comunitarios de Bienestar in Colombia (Centro de Estudios sobre Desarrollo Económico, cede, Universidad de los Andes, Working Paper Series, 2009-16, 2009). Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1486209

76Lidia del Pilar Serrato, Conciliación entre vida familiar y vida laboral: El caso del servicio de cuidado infantil en Bogotá (Tesis de grado no publicada para optar al título de Magister sobre estudios en desarrollo, Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación sobre Desarrollo, CIDER, Uniandes, Bogotá, 2008).

77Lidia del Pilar Serrato, Conciliación entre vida familiar y vida laboral: El caso del servicio de cuidado infantil en Bogotá (Tesis de grado no publicada para optar al título de Magister sobre estudios en desarrollo, Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación sobre Desarrollo, CIDER, Uniandes, Bogotá, 2008).

78Focus group. Bogotá - Colombia. San Cristobal Sur locality. October 17, 2012.

Bibliography

Books

Becker, Gary, A Treatise on the Family (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1991). [ Links ]

Benería, Lourdes, Gender, Development and Globalization: Economics as if all People Mattered (Routledge, London, 2003). [ Links ]

Departamento Nacional de Planeación, DNP, Agencia Presidencial para la Acción Social y la Cooperación Internacional, El camino Recorrido, Diez años de Familias en Acción (Presidencia de la República, Bogotá, 2010). Available at: http://www.dps.gov.co/documentos/FA/EL%20CAMINO%20RECORRIDO%20WEB.pdf [ Links ]

Escobar, Arturo, Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World (Princeton University Press, Princeton 1995). [ Links ]

Fraser, Nancy, Fortunes of Feminism: From State-Managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis (Verso, London, New York, 2013). [ Links ]

Kennedy, Duncan, A Critique of Adjudication [fin de siècle] (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1997). [ Links ]

Lipsky, Michael, Street-level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services (Russell Sage Foundation, New York, 2010). [ Links ]

Pitch, Tamar, Un derecho para dos: la construcción jurídica de género, sexo y sexualidad (Cristina García-Pascual, trad., Trotta, Madrid, 2003). [ Links ]

Reid, Margaret, Economics of Household Production (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1934). [ Links ]

Said, Edward W., Orientalismo (Random House Mondadori, Barcelona, 2004). [ Links ]

Sommer, Doris, Proceed with Caution, When Engaged by Minority Writing in the Americas (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999). [ Links ]

Spivak, Gayatri Chacravorty, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999). [ Links ]

Stiglitz, Joseph & Greenwald, Bruce, Towards a New Paradigm in Monetary Economics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003). [ Links ]