Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile Issues in Teachers` Professional Development

Print version ISSN 1657-0790

profile vol.19 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2017

https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.56209

http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.56209

A Learning Experience of the Gender Perspective in English Teaching Contexts

Aprendizajes de la perspectiva de género en los escenarios para la enseñanza del inglés

Claudia Patricia Mojica*

Universidad de Los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia

Harold Castañeda-Peña**

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia

*cp.mojica10@uniandes.edu.co

**hacastanedap@udistrital.edu.co

This article was received on March 15, 2016, and accepted on October 21, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Mojica, C. P., & Castañeda-Peña, H. (2017). A learning experience of the gender perspective in English teaching contexts. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 19(1), 139-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n1.56209.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons license Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Consultation is possible at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Eighteen Colombian English teachers participated in a course with an emphasis on gender and foreign language teaching in a Master's program in Bogotá. This text describes the design, implementation, and the learning in this educational experience. The analysis of the course was based on a view of learning as a process of participation rooted in the praxis of English teachers' classrooms. This experience reveals that gender is a relevant category in the frame of English language teacher education as it provides teachers with tools from a broader social and educational perspective. This reflection also leads to implications for teachers' practices with a gender perspective.

Key words: English teachers, gender and foreign language education, language teacher education, learning, participation.

Dieciocho profesores de inglés participaron en un curso con énfasis en género y la enseñanza de lengua extranjera, en el marco de un programa de maestría en Bogotá. Este texto describe el diseño, la implementación y los aprendizajes que surgen en esta experiencia educativa. El análisis del curso se basa en una comprensión del aprendizaje como el resultado de un proceso de participación en la práctica de la enseñanza de los docentes. Esta experiencia revela que género es una categoría importante en el marco de la educación de la enseñanza del inglés, por cuanto aporta elementos desde una perspectiva social y educativa. Esta reflexión revela algunas implicaciones para la práctica de docentes sensibles a la categoría género.

Palabras clave: aprendizajes, educación de docentes de inglés, género y educación en lengua extranjera, participación, profesores de inglés.

Introduction

One of the major commitments that the field of Education has assumed in the last decades worldwide is the incorporation of the gender perspective. Education is the means by which it is possible to reach gender equity1 and foster gender justice and fairness (Connell, 2011; UNESCO, 2015). In this sense, Colombia, like many other countries around the world, has attempted actions such as improving access to education particularly for girls/women; however, this has not been enough to transform gender relations in the school. The school is considered one of the social places for the gendered cultural reproduction; therefore, it has been suggested that the gender perspective be incorporated into the teaching framework, the curricular contents of all subjects, and into all teachers' professional development (Alcaldía de Medellín & Subsecretaría de Planeación y Transversalización, 2010; Calvo, Rendón, & Rojas, 2006; Fuentes Vásquez & Holguín Castillo, 2006).

Foreign language teaching contexts are not exempt from the responsibility of incorporating the gender perspective to help educational institutions battle gender inequities. These particular learning settings2 also display that meanings related to gender turn, in many occasions, into sexist practices, hegemonic ideas, or differential treatments that disfavor students' learning experiences (Hruska, 2004; Litosseliti, 2006; Sunderland, 2000b; Pavlenko & Piller, 2001). Some researchers claim that language teachers should be more aware of aspects such as gendered discourses of texts/contents and issues related to power during class interaction, as this may help or hinder learning opportunities, language access, and meanings that students may learn about gender representations (Castañeda-Peña 2008b; Hruska, 2004; Litosseliti, 2006; Sunderland, 2000a, 2000b).

Within this view, we argue that foreign language teachers should consider not only students' linguistic knowledge, but also the knowledge students learn through language socialization processes taking place in classrooms settings. This knowledge is related to culture, values, beliefs, and issues of morality and respect (Duff & Talmy, 2011). Furthermore, some scholars and teachers in the field of second language acquisition (SLA), bilingualism, and foreign language education (Hruska, 2004; Litosseliti, 2006; Pennycook, 1999; Piller & Pavlenko, 2001; Sunderland, 2000a, 2000b) claim that gender and language in the foreign language classroom are relatively untheorized and unexplored. Therefore, these authors have strongly recommended practitioners to include gender in their work, practices, and research interests.

Colombia presents some relevant research that points to the importance of gender in foreign language contexts (Castañeda, 2012; Castañeda-Peña, 2008a, 2008b, 2009, 2010; Durán, 2006; Rojas, 2012); nonetheless, these studies have not been tantamount to the inclusion of gender in English teachers' professional development. Foreign language educators have been largely informed by SLA research which focuses on cognitivist approaches to language learning, leaving gender on the margins (Piller & Pavlenko, 2001). Unless teachers' professional development (TPD) programs in teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL) education integrate gender awareness courses or seminars, English teachers will not be prepared to recognize ways in which gender meanings are transmitted and legitimated, and how gender inequities are (re)produced in their teaching contexts.

Teachers are key agents of change within this process and, therefore, need to receive training in these matters during their teaching professional development (Connell, 2011; Esen, 2013). In order to contribute to filling in this gap in TPD in TEFL education and have it aligned with this educational commitment, we offered an optional course for in-service English teachers in a Master program in Applied Linguistics to TEFL in Bogotá, Colombia, with a gender orientation. The objective with this course was to raise gender awareness within practices and contexts of teaching.

This article accounts for this course experience; thus, in what follows we will present the theoretical and methodological considerations drawn for the design/implementation of the course. The analysis of this course experience will be presented from two perspectives: First, a reflexive analysis of the learning process that we as teachers of this course experienced in relation to the methodology and objectives we aimed for. Second, we will explain the scope the student-teachers (STs) displayed within their teaching contexts and practices in relation to the gender awareness they developed through the course.

Theoretical Framework

This section shows some relevant theories helpful to understanding the approach of this course with a gender orientation in the field of English teaching. We draw on the critical approach to reflect on and question English teachers' roles in their daily praxis, and the components that should be included in the contexts of English teachers' education. Another theory implied here is what Wenger (1998) termed communities of practice (CoP); this learning approach reflects the methodology and teaching decisions made in the framework of this course proposal. Finally, we will present the concept of gender as a category constructed through interaction with others, as well as its importance in light of the course of identities and language learning.

Teachers' Professional Development (TPD) From a Critical Approach

There are various works that point to the teachers as actors that may reproduce gender inequality in educational scenarios (Calvo et al., 2006; Esen, 2013; Verma, 1993). This happens because teachers grow up in a society and transmit implicit and explicit values, expectations, and norms by means of which students are socialized to learn gender roles, gender relations, and gender behaviors and attitudes in society. Likewise, it has been claimed that teachers are fundamental agents to address and struggle gender inequalities in their teaching contexts (Calvo et al., 2006; Esen, 2013; UNESCO, 2015); for this aim, teachers should receive training in their professional development trajectory to help them gain gender awareness, reflect on it within the context of their practice, and find strategies to attempt to eliminate gender inequalities.

In Colombia there have been some experiences of TPD and gender equity that show important findings and understandings but they have not been permanent experiences within the field of TPD (Calvo et al., 2006). Some of these experiences, reported in this state of the art by teachers of different areas of knowledge, were designed and carried out by The Gender School of Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Asociación Distrital de Educadores (ADE), and the World Bank. Nonetheless, "teachers' continuing education has not incorporated gender equity in Colombia" (Calvo et al., 2006, p. 1). This is one of the challenges that prevail in the TPD in this country (Díaz Tafur, 2002). Therefore, it comes as no surprise that TPD for English teachers had not incorporated a gender perspective either.

A state of the art about English teachers' professional development in Colombia reveals that in-service teachers expect to find professional development programs that transform their working conditions, develop their teaching competence, and produce knowledge in areas such as classroom management, the teaching of values, and the relationship between the academic life and theirs/their students' fulfillment. What seems interesting for this discussion is that most of these TPD programs focus mostly on the second expectation, the development of the teaching competence, while leaving the others aside (Cárdenas, González, & Álvarez, 2010). Thus, for the purpose of including what TPD in TEFL education has been left out, the perspective of gender contributes to a great extent to enhancing the teaching practice. In this sense, critical theory becomes an important asset to analyze TPD in TEFL education; it calls for the acknowledgement that English teachers' role is not merely as instructional teachers, learning how to teach English, and whose main concern revolves around developing students' linguistic competence. English teachers also have social responsibilities as educators, that is, they need to understand the ways in which they are carriers of gender codes that reproduce inequalities and the ways in which hidden and formal curricula transmit and legitimate sexist behaviors, segregation, and discrimination (Calvo et al., 2006; Esen, 2013).

Hence, in accordance with the importance of including a critical approach to TPD for English teachers, as it prevents teachers from falling into these instrumentalist views of their practice and broadens the horizon of their practice and roles as political and social teachers, we can see that "educators need to approach learning not merely as the acquisition of knowledge but as the production of cultural practices that offer students a sense of identity, place, and hope" (Giroux, 1992, p. 170). We situate this learning experience within the field of the critical approach since it furthers the view of English teaching aimed to understand and critique assumptions connected to power relations and cultural politics that cause inequalities and discrimination in TESOL settings (Pennycook, 1999).

The Learning Perspective

The methodology of this course is based on the premise that teachers' learning is likely to be produced within their teaching settings and their particular conditions of work (Johnson, 2009). Thus, learning is seen as a process of meaning construction produced in people's daily practices (Wenger, 1998). CoP underscores the importance of the practice by viewing it as the epistemological site where it is possible to define how people learn and the ways in which they develop knowledge of that community. From this standpoint, it is argued that the meaning(s) people produce out of their personal experience of engaging in those practices is what counts as learning.

Accordingly, this view of learning helps us carry the tasks proposed to promote a meaningful learning within STs' teaching contexts. This learning perspective turns into a tool allowing teachers to become more aware of gender within the exercise of "theorize the practice and practice the theory" (Bullough as cited in Diaz Maggioli, 2012, p. 12).

Gender

From a postmodern perspective and acknowledging the contributions of scholars such as Butler (1990) and Foucault (1992), gender is understood as a sociocultural category by which the issue of the body is connected to everyday social and cultural practices and discourses. Litosseliti (2006) describes gender as the social behaviors, expectations, and attitudes related to being male and female; she asserts that the features that have been designated to the sexual difference are cultural constructions, socially determined and alterable. Yet, for the design of the course, and with the objective of understanding gender inequities in education and the possibilities for transformation, we positioned this social category as "discourses of multiplicities" (Castañeda-Peña, 2009, p. 25).

This pluralistic vision promotes the idea that "there is not a particular masculinity, but masculinities; and there is no single femininity, but femininities . . . both masculinities and femininities constitute and reconstitute subjects establishing permanently changing asymmetrical relationships in contexts where they participate" (Castañeda-Peña, 2009, p. 25). We believe understanding gender as "discourses of multiplicities" helps address the normalization of differential discourses and the endorsement of explicit and tacit ideas that cause gender inequalities. In other words, we can avoid centering our understanding of this category from a dualist and essentialist view of male/female, masculinity/femininity, or girls/boys, which favors the production of rigid, fixed, hegemonic, and often discriminatory connotations of how the genders should be or act.

This vision of gender, among other issues that were part of the course, would eventually give STs some tools to understand language learning as a socializing process for the construction of gender subjectivity and the (re)production of gendered rules, relations, practices, and representations in the setting of their language classrooms (Litosseliti, 2006).

Description of the Course

Identity and Language Learning was one of the optional courses offered within the Master program for English language teachers in a state university in Bogotá, Colombia. The course was implemented in the second semester of 2014. Although this Master program includes subjects related to social and cultural issues within the components of what in-service teachers should know, this was the first time a course with a gender emphasis was implemented in this graduate program.

The Participants

A total of 18 students, in-service English teachers, who are candidates in this Master program registered voluntarily to take this course. There were 13 women and five men; 10 teachers worked in state schools, three teachers worked in bilingual schools,3 four teachers worked in university programs, and one teacher who worked in virtual English online programs.

General Objective

A purpose of the course was for STs to be able to relate to issues of gender in their teaching environments. In other words, the course aimed at raising gender awareness and the relationship it had with their teaching practices and contexts. By enabling this, we planned to achieve the following specific goals:

- To identify different ways in which gender has been tackled in English language teaching (ELT) contexts.

- To increase knowledge about the issues research in the field of gender and language learning has pointed out.

- To reflect upon the readings and relate them to their particular teaching scenarios.

- To be inspired by other research works carried out by language teachers/researchers that evidence how they have dealt with or analyzed the category of gender in their teaching practices.

- To identify and apply approaches, concepts, methods, strategies, and reflections in their own teaching practices by using the perspective they have acquired about gender.

Teaching Approach

As a result of the learning perspective adopted (CoP, Wenger, 1998) and the vision of "participate and learn" (Diaz Maggioli, 2012, p. 12), the teaching approach focuses on situating the STs' gender awareness in real teaching conditions. Thus, STs participated through oral presentations and debates presenting their own opinions and reflections (there were written and oral pieces of work). There were guest speakers in some of the sessions; we thought it would be inspiring for STs to listen to some teachers who had researched gender issues in ELT contexts locally. Additionally, personalized tutoring sessions were offered for those STs who wished to get oriented in the practical tasks proposed in the course.

Tasks

Beyond the STs' active participation in debates and oral presentations, we wanted to propose two important activities to achieve the goal of situating STs' gender awareness in their teaching contexts. The first activity was a teacher's journal in which STs' observed their classes with the purpose of raising questions and problematizing those observations in the light of gender. The objective was to supplement what they had been reading in the course with what was actually going on in their classes.

In the second task, STs conducted a small-scale research. STs could do this exercise either by choosing a topic of the content of the course that seemed interesting to them, or by using information or aspects of their observation journals that were important, meaningful for them to inquire more; they used research techniques to collect data (interviews, class observations, etc.).

Contents and Resources

Gender has been an issue of interest in the field of education in general; nevertheless, we attempted to focus this perspective on the area of foreign language learning/teaching. This program sought to show STs that gender has been an important issue in their professional context, and therefore English teachers should also be concerned with these types of matters as part of their responsibilities as language educators. We organized the contents into four areas of the teaching practice: gendered interaction, language teaching materials, class contents, and teacher's pedagogy.4 Furthermore, the use of short videos, documentaries, and international and local research reports facilitated STs' learning.

Learning Outcomes

These learning expectations were framed on the abilities that STs were expected to achieve through the two tasks.

- To problematize their teaching contexts and practices in light of the gender category.

- To exemplify the perspective that they have acquired about gender through their small-scale projects.

Assessment

Taking into consideration the pedagogical proposal, it is clear that we needed to take the STs' products and their personal process—the presentation of their small-scale research projects, written reflections, observation journals, and their active participation in debates and presentations—as the means for the evaluation of the course.

The following section will describe what happened during the implementation of this course, and whether the proposal was relevant for STs' teaching practices.

Learning Outcomes of the Innovation

The outcomes of having implemented this cutting edge course are to be presented in two sections from which the issue of learning has a twofold effect; on the one hand, we will necessarily consider the course's teaching proposal: methodology, tasks, and contents. On the other hand, we will refer to the STs' learning within the framework of this course. Both standpoints, learning with respect to the teaching proposal and STs' learning, point to some important considerations for the field of English language teacher education as we will demonstrate through the discussion of this analysis.

The data used for this reflexive analysis derive from three sources: firstly, some tutoring meetings audio-recorded with the STs through which we attempted to gain understanding of their personal perceptions, questions, and concerns with regard to the contents and the tasks of the course; secondly, a questionnaire that was applied at the end of the course (see Appendix); and finally, the different written assignments through which STs reflected on their understandings of the contents of the course and the connections they made within their own teaching contexts. In order to avoid bias or monopolize the interpretations of this reflection, we drew on the voices of different STs of this course so as to re-construct what took place through this learning experience.

Learning With Respect to the Teaching Proposal

We will start by considering some of the challenges that we faced when addressing the contents of the course. Thus, for example, the concept of gender was intended to be presented, as stated in the theoretical framework, from a social and cultural approach rather than a product of the biological difference. Nonetheless, we noted that some of the STs were initially relating gender with the concept of sexual diversity, as it is presented in the following extract taken from the final questionnaire:

It is something totally ignored by most of teachers. For instance, I had never thought in the possibility or search gender issues in an English class. It sounded to me more refer to a psychological session to help a student to clarify his/her beliefs and positions towards his/her sexual orientation. What an ignorant I used to be!! [sic]

Given the fact that gender and sexual diversity are part of the field of sexual identity, it is frequent that these two concepts are treated or understood as interchangeable or the same issue, but they are certainly not the same. As teachers of teachers (ToT), we learned through this experience that this confusion may cause tensions among the STs of the class, as there may be STs who are interested in approaching a gender perspective in their teaching scenarios but not willing to deal with issues of sexual diversity.5 This is something we find worth reporting, as this common misconception would need to be addressed directly and from the beginning of a future similar (or same) course in order to avoid ambiguity and confusion. As we became familiar with this confusion, we decided to incorporate a class session in which the differences between these concepts were briefly stated.

Beyond presenting gender as a concept, we were expecting to help STs take note that gender is not a matter that is deemed to be the differences among boys/girls or men/women within the field of learning a foreign language. The next extract illustrates the way in which STs perceived this concept within their working context:

I learned that gender does not necessarily happen from a "male vs female or vice versa" perspective. It happens among or inside femininities and masculinities in the exercise of power. In my research process, I was able to see particularly that boys dominated other boys, and girls were not necessarily the "victims" as they are usually seen in most of the cases.

As it can be noted, gender is perceived as an issue that is co-constructed with others in the social interactions and, as this ST states in the extract, "it happens in the exercise of power." This extract evidences that the ST was able to find how gender operated within the interaction of her students in class. Furthermore, this ST draws on the multiplicity framework—when referring to "masculinities and femininities" (Castañeda-Peña, 2009)—to acknowledge that there is not one masculinity or femininity but different possibilities to be and perform as a boy/girl. This understanding was important since differential frameworks often may not be useful to recognize issues related to power and inequality across and among femininities or masculinities (Pavlenko & Piller, 2001).

Now we would like to refer to the methodology of the course and how STs responded to the pedagogical tasks we proposed. Certainly, this learning approach (situated in STs' teaching settings) appeared to be a good proposal to achieve meaningful learning; however, what appeared to be right also gave rise to moments of frustration and confusion, as acknowledged by this ST's response:

It was a cocktail of emotions, many times I was confused and did not see the concept of gender anywhere; I thought it was something imposed. I lived moments of discouragement and confusion. However, the collaboration with the group and observing other studies cleared my doubts.

This extract describes how some STs experienced the tasks of the observation journal and the small-scale research. As can be noted from the ST's perception—feelings of discouragement and confusion—this is a rather complex task that cannot be achieved just by looking at the classroom. The complexity of this task stems from learning to sharpen the view with regard to what is tacit, what is taken for granted, and what is embedded in natural and routinized teaching/learning environments. This is also a challenging task due to the fact that it is hard to problematize issues that usually pass unnoticed, as we may believe this is just the natural way of these learning environments. We could actually feel the effort STs were making to try to identify gender issues in their English classrooms (classroom dynamics, use of materials, the curriculum, etc.). Nevertheless, we were also able to see from other ST's samples that this was a process: It took some time for STs to acquire this gender view in their classes and understand the implications it brings to their practices.

The fact that STs had to comply with these tasks, as part of the course demands, certainly increased the pressure on having to write their observation journals. For instance, there were three students who told us they were willing to do the task of the observation journal but they had not been able to find any specific moments or aspects in their classes related to gender and language learning. The strategy here in order to help STs with this task was to use other STs' contextual samples in which gender was evident. We thought this strategy might lessen the confusion and discouragement, as STs could realize what their classmates were doing and how they were interpreting it. This was part of the CoP, where STs were able to share new understandings, doubts, and what they were learning in their classrooms with regard to this new perspective. Here we have one of the ST's examples from the observation journal that we used in class to show these STs' ideas of how gender could be identified in their class scenarios. The extract describes one event of a ST's English class in which her pre-school students were learning different professions:

But the it did not finished with the girl's question, when she was presenting herself, she said "My name is Michel, I am Pilot and I work at the airport" and a boy raised his hand and told me: "Teacher she did not do it right because she should have said flight attendant instead of pilot" and the girl said "I said it right because I want to be a pilota,"6 and when she said that some children laugh at her and I asked them not to do that because she was right. . . . In this case, language shows that there is not differentiation in words for this occupation "pilot" is piloto or pilota7 (pilota is possible to say it in Spanish),8 my student felt angry about it; maybe she was feeling this was not fair, because she has the total right to be whatever she wants even though there is no female name for that. [sic]

This excerpt shows when a ST recognized a gendered discourse. A gendered discourse is not as tacit or implicit as other types of classroom interaction issues. These discourses can be traced because they say something related to men or women. In this case, the ST notes how the use of this discourse produces power relations among her students creating discursive subject positions: "Gendered discourses position women and men in certain ways, and at the same time, people take up particular gendered subject positions that constitute gender more widely" (Sunderland, 2004, p. 22). What is interesting from this extract, besides helping the three STs who expressed difficulty writing in their journals, is that the ST who writes this journal entry can identify an unfair situation through gendered discourses of her English class. This leads us to think that through this observation task, STs were also problematizing gender in their contexts, as we had expected them to do.

The evident anxiety in the STs' process around this task cannot be avoided, yet we learnt that it may be reduced throughout the collaboration and dialogue with others. In this respect, Johnson (2009) highlights the importance of dialogic mediation and collaboration in the processes of teachers' learning:

Teaching as dialogic mediation involves contributions and discoveries by learners, as well as the assistance of an "expert" collaborator, or teacher. Instruction in such a collaborative activity is contingent on teachers' and learners' activities and related to what they are trying to do. (p. 63)

During the classes, we opened spaces to share STs' subjective experiences, understandings, and questions; they needed to be verbalized and analyzed in cooperation with other members of this CoP (Wenger, 1998). We perceived that there was a co-construction in the production of new meanings regarding these pedagogical tasks.

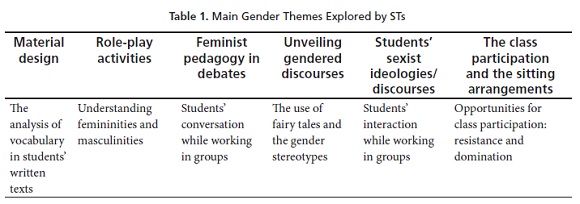

Despite the complexity of the small-scale research and the difficulties that STs reported while doing it, we found that this task allowed them to become aware of the importance of a gender view in their teaching contexts. Several STs reveal in their oral and written reports that they managed to discover and learn different issues in terms of their roles as English teachers, their possibilities to use this information to make changes in their teaching practices, and the importance of these views for their teaching practices. Although the next section will present STs' learning, Table 1 summarizes the themes addressed in STs' small-scale research studies. All of them were analyzed with a gender orientation and comprised a fundamental element of analysis.

STs' Learning Within the Framework of the Gender-Oriented Course

This section will present some of the aspects that STs identified through their small-scale research exercises with respect to the gender analysis in their teaching contexts. The following extract illustrates not only what the ST discovers in her practice but also accounts for the ST's ability gained through her research. This narrative account displays the moment of an English class in which teenage students coordinate a role play activity in the restaurant.

The host in the entrance of the restaurant (classroom) was a boy, most of the clients were families (parents and children) there were not waiters just waitress, they were five, the cashier was a boy and the manager too, but the cooks were women, while the girls were working very hard, their dialogues were longer, the boys had the easier performance. However, boys had the best position taking into account how a restaurant works. In addition, talking about the clients, families, the wives went into the restaurant walking behind their husbands and they did not ask for the reservation, the boys were the clients who appeared in the reservations' list. The waitress took the orders' men first. Certainly, I saw that women had many responsibilities and organized everything, but they were not the bosses. On the contrary, boys enjoyed some privileges with a less effort. [sic]

Unlike other examples in which gender is identified by explicit gendered discourse, this extract reflects that gender becomes an issue of reflection as the ST problematizes the way her students assigned gender roles that represent symbolically more advantageous social positions for boys than for girls—girls played more domestic roles and did not have important social parts in the sketch, e.g., they held more back-stage responsibilities. We perceived in this interpretation an ability that the ST gained since this situation could have passed unnoticed if she had not drawn on a gender view to understand this situation which was due to the routinized dynamics of organization in these sorts of typical English class activities. This analysis allows one to understand that through these subtle forms of organization the legitimation and reinforcement of gender relations and gender social positioning arise. It is precisely these types of subtle interactions which impact the gender subjectivities in the school (García Suárez, 2003). Furthermore, the ST manages to problematize two other aspects that are connected to girls/boys' learning experiences: the ST finds that girls have more difficult and longer dialogues to learn, as well as more responsibilities in the organization of the role play.

Another ST who explored his students' social relationships turned his attention to a problematic situation in which he reported sexist discourses among students. As he describes in his final written report of the small-scale research, he "observed behaviors and patterns related to gender that hinder[ed] and limited students' participation in class." This ST comments that in a group activity, a boy had conflicts with the girls of his group, and questions the ST for having him work with girls. When the ST tries to inquiry what is going on in the group he obtains the following reply from the boy:

Teacher: what is going on Camilo? Why don't you like that women talk to you?

Camilo: I don't know, maybe it is chauvinism...I do not listen to women, not even to my mum.9

In this particular situation, the ST describes some gendered discourses used by this boy in class that show sexist ideas that do not favor girls' images to justify the fact of not having to work with them. The question that remains in this case is how teachers deal with these types of gender relations in class. Teachers cannot simply insist students work without having any conflict during their group work.

Before discussing the learning acquired in this case, we will present another example related to the design of material that is connected to this reflection of the teachers' role. One ST designed a story using role reversals to study the topic of professions and illustrate some gender stereotypes. The main character of her story is a man who is looking for a job as a housekeeper in Bogotá. The ST wanted to expose her students to the idea that both women and men could be good housekeepers. From essentialist and patriarchal discourses, this is a job that is usually thought to be assigned exclusively to women/girls (Pérez, 2012). At first, the ST was interested in learning the type of gendered discourses that emerged when her students read the story. However, the ST manifested that although her students produced gendered discourses, she felt she did not know how to react towards these stereotypical discourses, as she did not want to impose ideas on her students or judge her students' imaginaries. As a result of this, this ST raises questions about her own role and the possibilities that might be available to her in order to promote more progressive ideas about gender beliefs and imaginaries.

As part of the STs' learning, we found that these two STs raised questions in relation to the ways they could address gender meanings that do not favor gender representations. STs realized that it was complex to react counter-hegemonically. We identify a concern towards this issue as they felt accountable for tackling those meanings that were taking place in their contexts. It would require that STs continue this process, as we believe it is through experience and in the exercise of their practice that teachers can gain expertise and a better understanding of how to deal with these responses in the classrooms. We also believe that the course did not directly provide STs with the tools to transform these situations.

Yet, we find it valuable that STs acknowledged that their roles as English teachers should go beyond teaching a linguistic code. As a matter of fact, STs manifested an interest in becoming agents of change in ways to create equal opportunities for participation and generating more progressive discourses as part of their practices. The next extract shows this point:

The project was then aimed at portraying gender positioning through the analysis of students' and teacher's daily interactions. As the findings showed a "subordinated" or "disempowered" group of students, boys and girls, who had apparent little human agency and were denied the possibility to access power and knowledge, a small pedagogical intervention was carried out in order to empower the "powerless".

This reply accounts for a ST's experience in her small-scale project. Through this, the ST manages to notice unequal opportunities in students' class participation. Based on this discovery, the ST created a pedagogical intervention (changes in her class participation dynamics) in which students who did not participate in class increased their opportunities in their class participation; as the ST says, she empowered them to do so. Hence, changes in teachers' practices are shaped by teachers' reflections and what they problematize in their classrooms, and not by the impositions of the methodology of the course. On this matter, this transformation in ST's practice was a product of her own decision in the process and reflection during their participation in our course and her individual learning processes.

Although we acknowledge the complexity of the course tasks, it was through the analysis of the data STs collected in their teaching settings that our participants started to discover particular things and meanings that had not been evident to them before. Hence, knowledge and abilities STs gained were not a product of empty readings or of trying to imagine what it would be like to consider gender as an analytical category for their teaching practices. These things learnt—translated in products such as the materials for TEFL, discoveries and reflections, and decisions—were produced in the engagement and the complexity of their daily practice (Wenger, 1998).

Conclusions

This course aimed at helping English teachers raise awareness on gender issues that occur in their classrooms or teaching practices. As a result of it, STs were able to achieve most of the learning objectives we had set up for this course. Thus, for example, STs managed to discover and identify some problematic situations that had usually passed unnoticed by them; for instance, aspects related to the identification of unfair situations, sexist discourses and behaviors, and asymmetry in class participation. These STs would not have been able to recognize all these problematic matters if they had not participated in this optional course and developed small-scale research in their teaching contexts. Consequently, we argue that English teaching education or TPD programs should turn their attention to these types of experiences to incorporate what is being left out, improve teachers' reflection processes about their practice and role, and equip STs with the attitudes, skills, and the knowledge that they would need to work towards the goal of gender equity in the foreign language teaching contexts. The analysis of the data indicates that these courses prevent English teachers, as we explain in the conceptual framework, to fall into instrumentalist views of their roles as English instructors. STs broaden their perspective of their roles as English teachers embracing a position as English educators with a social responsibility; this can be perceived in this reply of the final questionnaire, where we asked them openly if they would recommend the course to other English teachers:

I would strongly recommend it because we, teachers, must gain awareness on gender issues that underlie human relations in educational settings as well as the possibilities we have, as agents of change, to subvert socially constructed beliefs on gender that perpetuate social inequities.

Likewise, we noted that STs' learning implied, for some of them, to think of and implement strategies to avoid, for example, class participation imbalances. Nevertheless, we also observed that not all of the teachers were able to transform the issues they identified as problematic in their teaching contexts; this is meaningful within the teaching experience of this course as it allows reflecting on what is needed to be included in the course program. In this sense, we think that this course aimed solely to raise teachers' gender awareness; but it did not incorporate an explicit agenda through which STs could learn skills for combating aspects such as sexist discourses, students' gender imaginaries that favor a patriarchal view, or students' attitudes in regard to certain unfair gendered meanings. For this reason, we think it would be relevant to offer another course in which STs are provided with the necessary support and follow-up so as to find practical solutions to transform the issues of gender inequality identified in their classes.

Finally, it is important to assert that we do not intend to assume this teaching practice as a "recipe" for how and what to teach when considering a gender perspective in the field of TEFL. We are aware of the fact that there may be other ways to do this. Additionally, we expect to account for this course with the spirit and hope to initiate a debate, based on this experience, on what we think is meaningful and important in order to include the gender perspective within the field of TPD programs in TEFL. Unless this perspective starts occupying a more privileged place in research, theory, and in this current academic community's attention, this field of English teachers' education will remain gender blind and the possibilities to attempt to achieve gender equity in English teaching classrooms will continue being just isolated experiences in which only a few English teachers will engage.

1The terms gender equity and gender equality tend to be used interchangeably; there has not been a general agreement on the difference of these two concepts. Nonetheless, "gender equality is the result of the absence of discrimination on the basis of a person's sex in opportunities and the allocation of resources or benefits or in access to services. Gender equity entails the provision of fairness and justice in the distribution of benefits and responsibilities between women and men" (UNESCO, 2010, p. 17). Some people see the concept of equality as a more general objective, and equity is understood as a stage or strategy to achieve the first one (UNESCO, 2015). We will use here the term gender equity.

2Although this is not inherent only in foreign language classrooms as gender permeates other educational spaces and social settings outside the classrooms.

3Bilingual schools refer here to schools that teach subjects in English and Spanish.

4If the reader is interested in getting a deeper understanding on this, then a review of the following references will be useful: Hruska, 2004; Litosseliti, 2006; Norton and Pavlenko, 2004; Sunderland 2000a, 2000b.

5The aim of this course did not involve dealing with sexual diversity issues.

6The girl uses the word "pilot" in English but applies a grammar rule of Spanish which consist of adding the vowel "a" at the end of the word to reflect a female connotation.

7What the teacher means here is that in English the word "pilot" is sexless, and that is why it is possible to think of this occupation for men and women.

8The word "pilota" does not actually exist in Spanish.

9Our own translation from the final small-scale research report.

References

Alcaldía de Medellín, & Subsecretaría de Planeación y Transversalización. (2010). Propuesta para la incorporación del enfoque de equidad de género en los proyectos educativos institucionales "PEI" de instituciones educativas del Municipio de Medellín [Proposal for the incorporation of the gender equity approach in the institutions' educational projects of schools in Medellín]. Medellín, CO: Author. [ Links ]

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Calvo, G., Rendón, D., & Rojas, L. I. (2006). Formación y perfeccionamiento docente desde la equidad de género [Teachers' preparation and development from an equity of gender]. Retrieved from http://www.oei.es/docentes/articulos/formacion_perfeccionamiento_docente_equidad_genero.pdf. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L., González, A., & Álvarez, J. A. (2010). El desarrollo profesional de los docentes de inglés en ejercicio: algunas consideraciones conceptuales para Colombia [In-service English teachers' professional development: Some conceptual considerations for Colombia]. Folios, 31, 49-68. https://doi.org/10.17227/01234870.31folios49.67. [ Links ]

Castañeda, A. (2012). EFL women-learners' construction of the discourse of egalitarianism and knowledge in online-talk-in-interaction. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(1), 163-179. [ Links ]

Castañeda-Peña, H. A. (2008a). 'I said it!' 'I'm first!': Gender and language-learner identities. Colombian Applied Linguistic Journal, 10, 112-125. [ Links ]

Castañeda-Peña, H. A. (2008b). Positioning masculinity and femininity in preschool EFL education. Signo y Pensamiento, 27(53), 314-326. [ Links ]

Castañeda-Peña, H. A. (2009). Masculinities and femininities go to preschool: Gender positioning in discourse. Bogotá, CO: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. [ Links ]

Castañeda-Peña, H. A. (2010). "The next teacher is going to be...Tereza Rico": Exploring gender positioning in an all-girl preschool classroom. Magis, Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación, 3(5), 107-124. [ Links ]

Connell, R. (2011). Confronting equality: Gender, knowledge and global change. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Diaz Maggioli, G. (2012). Teaching language teachers: Scaffolding professional learning. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education. [ Links ]

Díaz Tafur, J. (2002, July). Plan de formación de docentes y directivos docentes de la Secretaria de Educación de Bogotá 1998-2001: estudio de caso [Teacher development program by the Secretary of Education of Bogotá 1998-2001: A case study]. Paper presented at the Conferencia Regional "El Desempeño de los Maestros en América Latina y el Caribe: Nuevas Prioridades, Brasilia, Brazil. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001347/134702so.pdf. [ Links ]

Duff, P. A., & Talmy, S. (2011). Language socialization approaches to second language acquisition: Social, cultural, and linguistic development in additional languages. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 95-116), New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Durán, N. C. (2006). Exploring gender differences in the EFL classroom. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 123-136. [ Links ]

Esen, Y. (2013). Making room for gender sensitivity in pre-service teacher education. European Researcher, 61(10-2), 2544-2554. https://doi.org/10.13187/er.2013.61.2544. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1992). Microfísica del poder [Microphysics of power] (3rd ed.). Madrid, ES: Las Ediciones de la Piqueta. [ Links ]

Fuentes Vásquez, L. Y., & Holguín Castillo, J. (2006). Reformas educativas y equidad de género en Colombia [Educational reforms and gender equity in Colombia]. In P. Provoste (Ed.), Equidad de género y reformas educativas: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Perú (pp. 151-203). Santiago de Chile, CL: Hexagrama Consultoras/FLASCO/Universidad Central/IESCO. [ Links ]

García Suárez, C. I. (2003). Edugénero: aportes investigativos para el cambio de las relaciones de género en la institución escolar [Edugender: Research contributions towards transforming gender relations at school] (1st ed.). Bogotá, CO: Universidad Central-Departamento de Investigaciones. [ Links ]

Giroux, H. A. (1992). Border crossings: cultural workers and the politics of education. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hruska, B. L. (2004). Constructing gender in an English dominant kindergarten: Implications for second language learners. TESOL Quarterly, 38(3), 459-485. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588349. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E. (2009). Second language teacher education: A sociocultural perspective. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Litosseliti, L. (2006). Gender and language: Theory and practice. New York, NY: Hodder Arnold. [ Links ]

Norton, B., & Pavlenko, A. (2004). Addressing gender in the ESL/EFL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 38(3), 504-514. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588351. [ Links ]

Pavlenko, A., & Piller, I. (2001). New directions in the study of multilingualism, second language learning and gender. In A. Pavlenko, A. Blackledge, I. Piller, & M. Teutsch-Dwyer (Eds.), Multilingualism, second language learning, and gender (pp. 17-52). Berlin, DE: Mouton de Gruyter. https:/doi.org/10.1515/9783110889406. [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. (1999). Introduction: Critical approaches to TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 33(3), 329-348. https:/doi.org/10.2307/3587668. [ Links ]

Pérez, A. (2012). Género y educación superior: más allá de lo obvio [Gender and tertiary education: Beyond the obvious]. Educar en la Equidad: Boletina Anual, 2, 64-75. [ Links ]

Piller, I., & Pavlenko, A. (2001). Introduction: Multilingualism, second language learning and gender. In A. Pavlenko, A. Blackledge, I. Piller, & M. Teutsch-Dwyer (Eds.) Multilingualism, second language learning, and gender (pp. 1-13). Berlin, DE: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Rojas, M. X. (2012). Female EFL teachers: shifting and multiple gender and language-learner identities. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(1), 92-107. [ Links ]

Sunderland, J. (2000a). New understandings of gender and language classrooms research: Texts, teacher talk, and student talk. Language Teaching Research, 4(2), 149-173. [ Links ]

Sunderland, J. (2000b). Review article: Issues of language and gender in second and foreign language education. Language Teaching, 33(4), 203-223. https:/doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800015688. [ Links ]

Sunderland, J. (2004). Gendered discourses. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. https:/doi.org/10.1057/9780230505582. [ Links ]

UNESCO. (2010). Reorienting teacher education to address sustainable development: Guidelines and tools. Bangkok, TH: Author. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001890/189054e.pdf. [ Links ]

UNESCO. (2015). A guide for gender equality in teacher education policy and practices. Paris, FR: Author. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002316/231646e.pdf. [ Links ]

Verma, G. K. (Ed.). (1993). Inequality and teacher education: An international perspective. London, UK: Falmer Press. [ Links ]

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https:/doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932. [ Links ]

About the Authors

Claudia Patricia Mojica holds an MA in Applied Linguistics from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. She is a doctoral candidate in Education at Universidad de Los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia). She is interested in teachers' education, social issues related to subjects' identities in language learning environments, and qualitative research methodologies.

Harold Castañeda-Peña holds a doctoral degree in Education, Goldsmiths, University of London. He is an assistant professor of the School of Science and Education at Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (Bogotá, Colombia). He is interested in gender, information literacy, and videogaming in relation to language learning and teacher education.

We would like to ask you some questions about the course we have just finished. This is not part of your evaluation process, thus it is important to be as clear and honest as possible.

- What meanings or new discoveries were you able to make throughout the course?

- How can we perceive gender in our own teaching environments? Provide examples.

- If you had to tell someone what this course was about, what would you say?

- Would you recommend the course? Why?

- What lessons learnt, if any, did you construct by means of your research process?

- How did you feel throughout the development of your small scale research project? Engaged, frustrated, motivated, and other? _________. Try to explain why you felt like this.

- What type of difficulties will English teachers encounter if they are to have a gender perspective in their teaching practices or in their learning environments?

- Do you feel that what you learned in this class is transferable to your teaching practice? If so, why?

- Will you keep gender in mind when teaching English?

Thanks for your answers!!!