Introduction

The contested concept of victory

Declaring winners and losers is a habitual outcome of a binary understanding of war, conflict, or fight where the endgame is marked with an absolute understanding of control and power of one party over the other. However, binary outcomes, namely victory or defeat, of past centuries large-scale interstate wars have dramatically eroded because of the dramatic variance in characteristics of wars and warfare. While victory by nature is a term developed and used purely in the military context of earlier eras, today's wars and conflicts do not hold this term in its original meaning. This is mostly because the lines between the trinity of war (the state, the people, and the army), as defined by the famous war philosopher Carl von Clausewitz's (1976), have been greatly blurred in small wars (Griffin, 2014). In these wars, the central axis of the conflict occurs between the state and a violent non-state actor, an insurgent (often the inferior party). Gleditsch et al. (2002) and many others (e.g., Licklider, 1995; Hartzell, 1999; Dupuy & Rustad, 2018; and Harbom & Wallensteen, 2005) report that limited/small wars are the most common type of wars since the Second World War. This type of small wars, where there is a state and non-state actor(s) as insurgencies fight, conceptualized as intrastate conflicts by Sarkees, Wayman and Singer (2003) and UPPSALA Conflict Data Program (UCDP)1, yield vital differences in the character of war where a purely military concept of victory is less relevant and potentially misleading in certain aspects. Hence, if victory in war is expected to be a total defeat or unconditional surrender of the enemy resulting in the termination of a conflict, such victory can hardly ever be achieved in the case of counterinsurgency (COIN) campaigns.

Insurgencies, by definition, are political organizations representing the dissenting indigenous inhabitants. As the French theorist and practitioner, David Galula, pointed out, only 20 percent of insurgencies are military while the rest of the eighty percent are political (Galula, 2005). In this respect, there is no purely military solution in a counter-insurgency campaign; even though states' conventional military efforts might bring the military defeat of insurgents. Insurgents who are comprised not only of military branches but even more so of social and political entities (Kitson, 1977), implying that a potentially successful COIN campaign is to be 80 percent political and only 20 percent military.

In all these regards, use of the term victory in its classical meaning in a COIN campaign is highly problematic. Victory by definition denotes an end goal (of a military defeat of the enemy), but such a result is not decisive in bringing the insurrection to a sustainable non-violent end. The social and political domains -the major part of the insurgent problem- might be negatively influenced by a military defeat, if not carefully and sensitively managed. However, a state's military victories over the insurgent group or the insurgent's military defeat are only a small part of the story. Thus, we need another term that better applies for the assessment of COIN effort because the classical meaning of victory refers to something that has a very little chance of realization (Callwell, 2013). In this context, rather than a new definition of victory, success, with a proper approach, is to be used to assess states' counterinsurgency campaigns. We will argue that success is a better fitting choice of a concept for three reasons. First, success focuses on political solutions. Success shifts perception from one-sided victory to a favorable outcome for all parties involved. Finally, because the outcome in COIN is not merely a victory or a defeat, as this paper will show, referring to the completed phases as a success, offers better accuracy.

The literature on small wars and insurgencies has already posed the question of a necessary reconceptualization of the notion of victory in the contemporary small wars, which has been more prevalent after the Second World War (Reiter & Stam, 2002; Fortna, 2018). However, the concept of victory and defeat for intra-state wars is limited within the existing literature (Baldwin, 2016, the sanctions debate; Angstrom, 2011) and very little attention has been devoted to the concept of success in small/limited wars, in particular, home-grown intra-state conflicts. The fact that this type of asymmetric conflicts has outnumbered the interstate since the end of the WWII (e.g. Gleditsch et al., 2002; Harbom & Wallensteen, 2005; Licklider, 1995; Hartzell, 1999; Dupuy & Rustad, 2018), and more importantly, that this type of conflict does not seem to be abated in the near future (Angstrom, 2011, p. 4), begs critical analyses of the concept of success in small wars. With the rising prevalence of small wars, strategies for conducting and countering them will gain even more importance, over time.

As one of the intractable conflicts in recent times of the world history, Turkey's conflict with the Kurdistan Workers' Party (Partiya Karkeren Kurdistâne, PKK) reveals a valuable example of an insurgency, Turkey's long attached pursuit of unilateral military victory and PKK's adaptation in a prolonged strategic tit-for-tat. After its military defeat in a more direct fight in the initial terms of the conflict, the PKK has pursued a broader socio-political campaign by relying on asymmetric warfare and indirectness in conflict. Turkey's war against the PKK officially commenced in 1984 and has been ongoing for almost 35 years, resulting in approximately 50,000 fatalities, some 6,000 civilian casualties (Ünal, 2016a, Gürcan & Ünal, 2018). Turkey has implemented different countermeasures in its struggle against the PKK that range from enemy-centric, oftentimes repressive and iron-fist measures, to population-centric approaches, including accommodative and conciliatory measures with less emphasis on the use of armed forces. However, the central theme of Turkey's countermeasures has been around seeking a decisive unilateral military victory in pursuit of PKK's demise (Ünal, 2012a, 2016a). In fact, the Turkish Army defeated the PKK (Kayhan-Pusane, 2015) in the military sense after its first-decade insurrection in 1993/94. As explained later, the PKK's founding leader, Abdullah Ocalan, acknowledged the PKK's military defeat in a direct challenge of Turkish state and authority. However, this military defeat was by no means a decisive result. Because of many reasons concerning the changing character of wars, particularly, small wars in the context of asymmetry, irregularity, and hybridity, it did not bring the PKK's demise at any level (social, political, military).

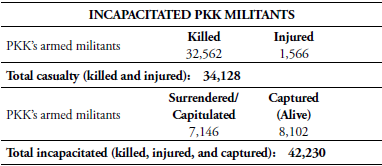

Despite the high death toll, the PKK has been resilient. It has managed to survive by changing its political strategies and adapting to the shifting socio-political and security environment despite Turkey's efforts to psychically eradicate it (Gürcan & Ünal, 2018; Kayhan-Pusane, 2015; Ünal, 2014; 2012a, 2016a). This strategic interaction has yielded many learning opportunities. It has had many turning points in which the conflict has undergone different phases and reached critical breaking points in its life cycle that have trapped both parties in a costly, almost four-decade deadlock, indicating PKK's resilience (Ünal, 2016a, 2016d; 2014; Ünal & Harmanci, 2016). The above is highly related to the notion of an asymmetric conflict, which is often referred to as new wars or hybrid wars, in which the insurgent (inferior, underdog) no longer pursues a capacity-oriented fight, but a will-oriented one by exploiting all the notions of asymmetry against a rule-bound state. As the result of the military campaign conducted by the Turkish Armed Forces (TAF), 32,562 PKK militants were neutralized, while 1,566 were injured, 8,162 captured and another 7,146 were surrendered (Ünal, 2016d).2

Given the discrepancy between a military victory and the successful termination of a conflict, as partly discussed above and later in this paper, this study first reviews the Turkey-PKK conflict, pointing out the failure of the concept victory in the particular case study. Later, it engages in a discussion on military victory and the essential concept of success in intrastate conflicts in which a state and a non-state actor struggle -either consciously or subconsciously- over perceived legitimacy by key populations. Lastly, this study applies the discussion into the reviewed case of the PKK conflict. The PKK conflict will be reviewed in two phases. First, the initial conflict phase in which the two parties were confronted by all their unilateral means and the Turkish Army quelled the PKK and impeded its initial end-state of territorial control and secession. It particularly focuses on how the nature and characteristics of PKK violence have changed after its military defeat to more asymmetrical and indirect forms concerning location, target status, and objective of violence. All of these negate the pursuit of military victory and necessitate a successful approach in a broader political campaign. Second, the study briefly outlines the rest of the conflict period. It reviews the PKK's resilience in the context of asymmetric and irregular warfare, showing the PKK's strategic shift in military and political (end-state) terms, negating the Turkish Army's earlier defeat. Overall, the focus is given to the decisive and consecutive phases. In the former, both parties pursued a capacity oriented fight for victory while, in the latter, the PKK gradually switched to a will-oriented fight that revealed significant shifts in the character of conflict and the nature (form, location, target status) of violence.

The PKK

Historical context

Kurdish dissent is a deep-rooted historical issue that dates back to the Ottoman times. The latest Kurdish unrest, as an ethno-national identity conflict, re-emerged in both internal and external contextual dynamics in the 1970s as part of the new cycle of national awareness that was universally induced by the nation-state phenomenon of the Cold War and post-Cold War eras, which coincides with the third wave of modern terrorism or the "new left wave" as classified by Rapoport (2004). Reflecting these features, the PKK emerged as an idea in 1973 and ideologically mobilized later during the 1970s. Abdullah Ocalan officially founded the organization on November 27, 1978, in Diyarbakir-Lice province (Ünal, 2012a; Ünal & Harmanci, 2016). Ocalan, the founding father of the PKK, openly stated in the initial manifesto that the PKK would enforce a Kurdish armed mobilization by engaging in a guerilla war, in which all the Kurdish people were involved militarily in a struggle for independence (Ocalan, 1978).

Leaning on the historical roots of Kurdish dissent, the PKK aimed at founding an Independent 'United' Kurdish State in the Middle East, comprised of various territories of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. Inspired by the Cuban Revolution, the PKK resorted to Maoist Strategy (MS), as Mao Zedong suggests (Kocher, 2007). As specified in the PKK's founding manifesto (The Path for Revolution in Kurdistan) (Ocalan, 1978) in its first founding Congress of 1978, the PKK leaned on a typical three-echelon structure from the "Theory of People's War" to reach its goal, namely, strategic defensive, equilibrium, and offensive. The PKK imagined a revolution emanated from the agrarian Kurdish peasantry living in rural areas of southeastern Turkey to metropolitan areas, as part of the Maoist theory (Ünal & Harmanci, 2016; Ünal, 2012a). Seen in this light, the PKK declared itself to be a socialist liberation movement with Marxist-Leninist ideology. After officially setting up its primary organizational goals and strategy in its initial Congress in 1978, the PKK held its first Conference in July 1981 and second Congress in August 1982. Following the 1982 Congress, the PKK leadership, predominantly stationed in the Northern Iraq and southeastern part of Turkey, officially commenced its war against the Turkish State in 1984 (Ünal, 2016c).

Confrontation (allegedly decisive) phase: the military defeat of 1993/94

After the strategic defensive between 1978-84, a preliminary phase for its guerilla fight, the PKK officially initiated its war on August 15, 1984, with two attacks in Semdinli and Eruh Districts in which one soldier was killed, and 12 were injured, three of whom were civilians. In the initial war period, the PKK directly challenged and confronted security forces which, as it perceived, were the representatives of Turkish political authority. As part of its MS strategy, the PKK conducted attacks on military outposts, remote hamlets, and villages where the governmental existence is weak in control.

The parties clashed militarily in a more a direct battle between armed apparatus of both parties. The PKK sought (political end-state) territorial separation to out-fight Turkish forces and employed the second stage of MS (strategic equilibrium) until 1990, and strategic attack between 1990 and 1993/93, during which they conducted direct challenges through isolated hit-and-run attacks on the army bases and outposts. In alignment with its strategic equilibrium phase, in 1986, the PKK replaced its individual attack Kurdistan Independence Units (HRK) with its army, the People's Independence Army (known as the Artesa Rizgariya Gelê Kurdistan, ARGK) and conducted raids with convened groups of up to 600 in the initial terms of the conflict. The PKK strived to attrite government authority in Turkey's south and southeastern region.3 To that end, from 1984 to 2000, the PKK employed selected violence against official government staff" as part of its out-fight strategy and conducted 23 attacks against the mayors and statesmen in cities and villages that resulted in eight dead and three wounded. The PKK also killed 27 imams and 116 teachers (Ünal, 2012a). It employed indiscriminate violence against non-compliant Kurdish peasantry to mobilize popular support by force and intimidation, as designated Ocalan's founding Manifesto (Ocalan, 1978).

The PKK's rural insurrection caught Turkey off" guard. Until 1987, it considered the PKK surge as a "bunch of bandits" to be dealt with by the responsible law enforcement unit, the Gendarmerie, which -at the time- was part of the TAF but serving as a public order maintaining law enforcement unit with jurisdiction in rural areas. Thus, no specific military action was taken. At the time, Turkey was experiencing political turmoil among ideologically competing groups in urban metropolitan areas, and martial law was underway since the coup d'état in 1980. After 1987, the TAF started to modify its military strategy and stationed different army bases throughout the region to maintain better territorial control, called Zone Doctrine/Areal Control. However, this approach was not designed for countering irregular or asymmetric warfare; this strategy stationed battalion army bases in rural areas to control the region considered easy targets for the PKK. In the early periods of the confrontation phase (1984-1993/4), the PKK conducted numerous raids on these bases with groups of 100-150 that convened and reached up to 600 armed militants, among them the Hakkari-Serin (9 soldiers killed in 1985), Samanli (10 in 1991), Cobanpinar (6 in 1991), Taslitepe (11 in 1991), Uzumlu (15 in 1992), and Tasdelen (27 in 1992).

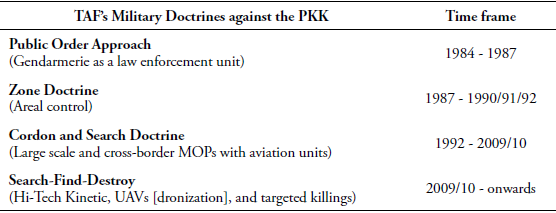

From 1990 and 91, the TAF gradually shifted to a new doctrine called Cordon and Search, in which PKK groups were detected (using HUMINT and SIGINT radio signals) and surrounded within a large cordon. The perimeter was then tightened through searches to engage and incapacitate armed militants through large-scale military operations (MOPs). The TAF began to use land aviation units with Cobra helicopters against PKK militants who had taken advantage of the rough terrain in the region. By switching over to Cordon and Search, the Turkish military became more proactive and militarily defeated the PKK on the ground. The TAF's military doctrines in its military operations until 2000s are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1 The TAF's military doctrines until the PKK's Military Defeat.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Turkey’s initial aim was to defeat the PKK militarily, deny its territorial control, and physically eradicate and exterminate it, as well as pro-PKK ideology (with the denial of Kurdish identity, linguistic, and cultural rights until the early 1990s) (Ünal, 2011). To supplement its strife for a decisive military victory, Turkey employed specific security measures. In 1985, Turkey established the Geçici Köy Koruculuğu (GKK; village guard system) in which the TAF trained and armed volunteer Kurdish villagers to counterbalance the PKK’s social mobilization effort from rural villages (Gürcan, 2015). The PKK reacted harshly to this policy that directly blocked its main strategy. The revolution emerged from rural to urban areas and produced 15 carnages in the provinces of Sirnak, Mardin, and Siirt. The carnage in the village of Pinarcik (located in the Omerli district, in the province of Mardin) resulted in the killing of 30 Kurdish civilians, including 16 children, and 8 GKK members (Ünal, 2012a). An emergency rule was proclaimed in the region in 1987 to enable the TAF to take de facto charge of the region. Turkey also implemented a forced evacuation policy in which remote hamlets and villages were merged into larger and safer communities for better governmental control. The uncertain conditions of the conflict had already compelled most of the resident Kurds to leave their original territory.

The TAF conducted several large-scale MOPs, including some cross-border operations starting in 1992. The Turkish Air Force continuously carried out offensive airstrikes against the PKK camps in Northern Iraq, which has served as a safe haven for the PKK since its inception in 1978. In total, there have been several cross-border (in Northern Iraq) MOPs at varying scales. Among these, however, only the seven that fall within the period analyzed here will be listed (see Table 2).

Table 2 Prominent cross-border MOPs against the PKK.

| YEAR | CODE NAME | PKK | TAF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Killed | Injured | Killed | Injured | ||

| 1992 | (No Code Name) | 1551 | 1232 | 28 | 125 |

| 1994 | Operation Dragon-1 | 146 | unknown | 5 | 0 |

| 1995 | Operation Steel | 555 | 13 | 64 | 185 |

| 1995 | Operation Dragon-2 | 204 | 89 | 21 | 0 |

| 1997 | Operation Hammer | 2730 | 415 | 114 | 338 |

| 1997 | Operation Dawn | 865 | 37 | 31 | 91 |

Source: Bulut (2014).

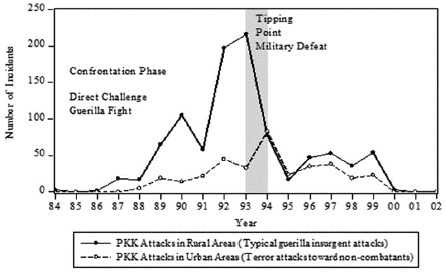

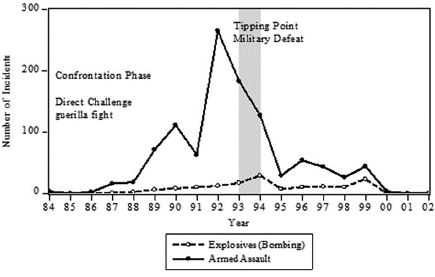

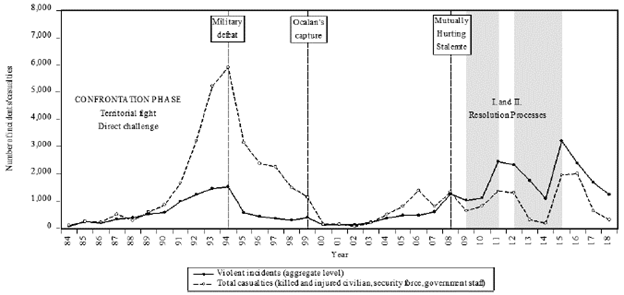

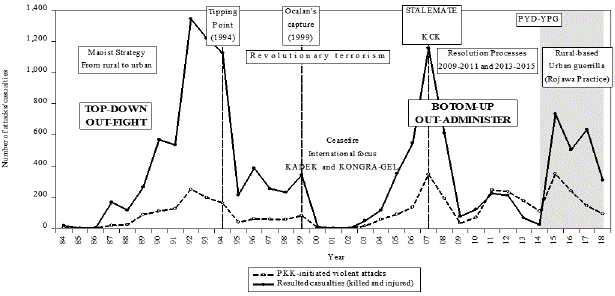

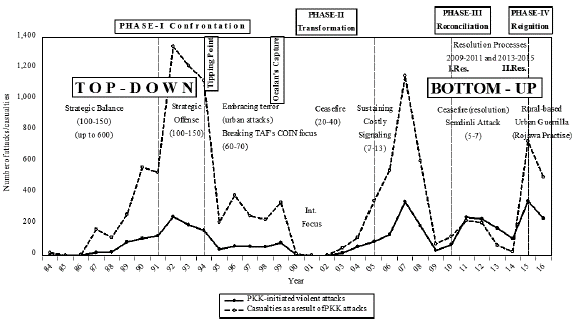

The cordon and search doctrine successfully prevented the PKK from realizing the third stage of its Maoist Strategy in taking control of the region. The impact of Turkey's cordon and search doctrine can be seen in Figures 1 and 2. While the aggregate (both results of MOPs and PKK attacks) level of violence (Figure 1) maintained its increasing trend until 1994, the PKK-initiated violence level started decreasing in early 1992 (Figure 2), indicating a lagged effect of the change in time and space initiative on the battlefield in favor of the TAF, based on the doctrinal shift in military strategy in 1992.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 1 Number of aggregate violent incidents resulting from PKK attacks and security force operations that resulted in casualties (civilians, security forces, and GKKs), 1984-2018.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 2 Number of PKK-initiated violent incidents resulting casualties (civilians, security forces, and GKKs) 1984-2018.

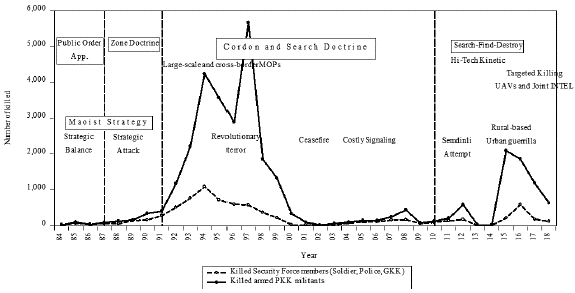

As a result of the success of this military doctrine and large-scale MOPs, the PKK had significant losses in its guerilla force. Approximately 8,000 PKK militants were incapacitated (and another nearly 3000 were either injured or captured) only between 1991 and 1994, as plotted in Figure 3.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 3 Killed Turkish security force members versus PKK armed militants.

In 1993, Ocalan -between the lines- acknowledged the PKK's military defeat in a press conference with Jalal Talabani (leader of Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, PUK). Ocalan stated that following 9 years of war the time had come to shift to non-violent political means. Another confession came in his public statement to the pro-PKK periodical Serxwebun's April Volume in 1994. He declared that the PKK would need at least 50,000 guerillas to reach an insurgent victory in the region; at the time, the PKK had between 8,000 and 11,000 guerillas. Moreover, the same volume of Serxwebun published the headline "In 1994, there could either be political or military solution" (Serxwebun, 1994). With this, Ocalan acknowledged military defeat by implying that the PKK's unilateral means at the time was not sufficient for a direct challenge of the state's authority and, for the first time, he referred to a political solution.

The PKK's dramatic shift from seeking military victory to success: from a capacity-oriented effort to a will-oriented fight

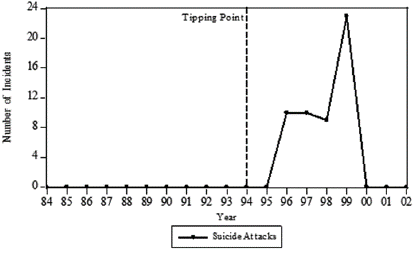

In terms of military victory and success discussed in this article, the PKK's military defeat on the ground in 1993/1994 was a crucial milestone in the conflict. Upon its defeat on the battlefield, the PKK gradually switched from conventional-style fighting, supplemented by guerilla tactics, to more 'asymmetric' means such as terrorist attacks in order to preserve its existence. The character of violence employed by the PKK indicated a dramatic variation, from mostly massive armed attacks on army posts (and intimidation-oriented indiscriminate violence against GKK members and their families) to bombings, assassinations, and suicide attacks in the western cities of Turkey to discredit the government's monopoly of violence, as well as to break the TAF's military focus in the emergency rule region.

The purpose of the violence shifted from direct challenge for territorial control of the southeastern region through military victory to the indirect and more asymmetrical challenge of coercing Turkey into a political compromise by attacking its will-to-fight by seeking success in a political campaign supplemented with terror and guerilla attacks to put both a physical and moral strain on the government. This shift strongly suggests that the PKK quit pursuing military victory in a direct sense and started seeking a success in realizing its overarching goal of self-determination in certain parts of Turkey in an indirect way of bringing Turkey to the negotiation table. In other words, the PKK gradually started relying on exhaustion (costly signaling) by provocation and attrition rather than extermination, (for different objectives of terrorism see Kydd & Walter, 2006) and attempted to erode Turkey's will to continue this costly struggle.

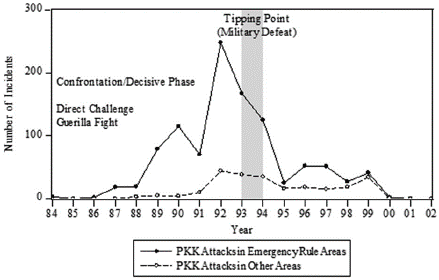

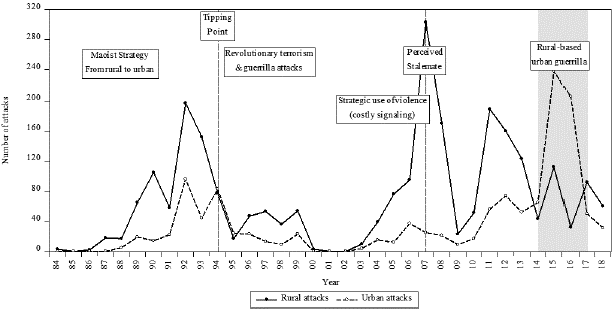

The PKK's deviation from seeking military victory in a capacity-oriented direct fight towards an indirect fight by exploiting asymmetry in its favor is evident. First, the PKK expanded its fight beyond the Kurdish-populated region (the critical region for the conflict) that claimed its independence. As plotted in Figure 4, after 1994, the PKK's attacks in emergency rule areas and non-emergency rule areas slope toward each other, indicating a proportionate increase in PKK attacks in western cities. However, in Figure 5, the PKK's urban attacks show a proportionate increase and almost converge with rural guerilla attacks after the conflict's tipping point in 1994. In Figure 6, the number of bombings proportionately increase as a more convenient incident type in urban terror and slope toward the number of guerilla attacks.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 4 Location of violent incidents, emergency rule provinces (southeastern provinces) vs. non-emergency rule provinces (1984-2002).

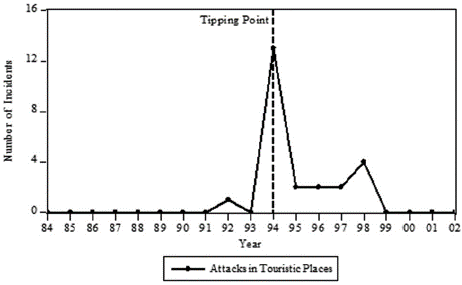

Moreover, the PKK resorted to typical terrorist attacks in western areas of Turkey. For instance, the PKK conducted suicide and terror attacks in tourist areas against civilians in the western metropolitan areas of Turkey, as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 8 Number of PKK-initiated violent attacks targeting tourist locations.

As seen in the figures, both trends indicate emergence and increase after the PKK's aforementioned shift in strategy and a dramatic shift in the PKK's strategy from directly challenging the security forces in the southeastern region in order to exterminate and establish an autonomous Kurdish State and indirectly and more asymmetrically coerce Turkey into a political compromise by targeting civilians in western regions using more urbanized violence. In other words, the PKK quit seeking military victory and seeking success in a broader political campaign in which military action was inferior or supplementary or complementary in contrast to earlier terms where the military means were the essential and only instruments of its fight.

The PKK's transformation: more politico-less military character

After this critical milestone, almost the entire character of the conflict changed. The PKK, as a politico-military organization, not only shifted its strategy in a military sense but also shifted in the character of violence they employ, embracing a more politico and less military structure and acknowledging the importance of legitimate popular support for its insurgent cause and campaign. Ocalan allowed a pro-PKK political party to be established in Turkey and they founded the Halkin Emek Partisi (HEP; People's Labor Party) on 7 June 1989. The PKK understood the advantages of legal, political activities in mobilizing the civilian population and considered political activities advantageous to its strategy of creating a 'people's war' by drawing popular support from the masses. Later in the process, there has been a number of pro-PKK political parties serving as the political wing (Ünal, 2012a). Given that some of them were shut down by the Turkish Constitutional Court on the grounds that these political parties counter the indivisible unity of the Turkish state, the PKK leadership always reserved another party as a successor to substitute its closed predecessors (Ünal, 2012b).

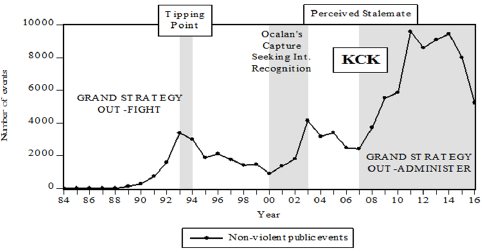

The PKK adopted a new grand strategy to place international pressure on Turkey to reach a political compromise. In alignment with Ocalan's call, the PKK transformed itself in 2000 by reiterating its most prolonged unilateral cease-fire. The PKK abolished itself twice, founded the Congress for Freedom and Democracy in Kurdistan (KADEK), respectively, in its 8th Congress in 2002. It renamed itself as the Kurdistan People's Congress (KONGRA-GEL) in 2003, officially embracing non-violent means to acquire international legitimacy over the reduced political goal (constitutional recognition of Kurds in Turkey). Between 2000 and 2004, the PKK focused on political recognition as a legitimate and official representative body for Kurds in the international arena by accelerating its front activities in Europe, backed by mass demonstrations in Turkey, evident in the increased level of non-violent pro-PKK public events during these years (Figure 9). As David Romano (2012, p. 229) puts it, "Influencing non-state actors based outside one's state boundaries, however, presents a more complicated challenge." Starting in 2002, as a result of Turkey's diplomatic efforts, the PKK was recognized as a terrorist organization by numerous countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and the European Union (EU). Thus, the PKK resorted to its old practices starting from mid-2003 (as indicated in Figure 1 and 2) and officially declared its rebirth.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 9 Level of non-violent pro-PKK public/civil disobedience events.

Following the less military structure and more political trend, the PKK founded the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) in 2007. The KCK is a trans-national political umbrella organization to pursue a pro-PKK political campaign and carry out de facto applications of autonomy in the region. The KCK dealt with social, economic, political, ideological, and self-defense issues based on its own. The creation of the KCK produced a new grand strategy. The objective of the KCK was to realize Ocalan's proposed Democratic Confederalism through 'out-administering' in a bottom-up approach as opposed to the top-down 'out-fighting' approach employed in the initial years of the conflict. With the creation of the KCK/TM (TM stands for Assembly of Turkey, since the KCK covers pro-PKK activities in host states of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria), the PKK pursued a power-sharing termed democratic autonomy, which sought a self-determination within a decentralized administrative system. This shift was a result of the PKK's gains in the socio-political arena through intense social engagement, widening popular support via embracing different societal segments, boosting Kurdish activism in and outside of Turkey, among others. As seen in Figure 9, pro-PKK public demonstrations and civil disobedience incidents indicate an increasing volatile trend in the entire process. However, this trend shows a steady increase after the KCK was been founded.

As part of its pursuant of success with a broader socio-political campaign supplemented with asymmetrical warfare, rather than a victory in military terms, the PKK had gradually changed its military strategy after losing the territorial fight. As opposed to conventional and semi-conventional tactics using large numbers of armed militants, the PKK limited its mobile groups to approximately 60-70 fighters after 2000, to strengthen secrecy and mobility. Before that, in the early years of the conflict, the numbers ranged from 100-150 (convened into 150-600 for army outpost raids). After 2007, this figure decreased even more, to 7-13 and sometimes even down to 5-7 as depicted in Figure 10. In this regard, the PKK abolished its army called the ARGK and created the People's Defense Forces (HPD) in which the PKK units were downsized for more mobility and secrecy for application of more asymmetry in nature.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 10 Introductory depiction of the PKK's response in military strategies and tactics throughout the conflict.

In sum, the PKK's grand strategy changed from a top-down military victory to a bottom-up politico-military approach with active social and political engagement with the KCK to keep the threat in the forefront of the government's agenda as well as keeping international attention. It leaned on the microeconomic concept of diminishing return rate, meaning that more militants meant easier detection, less secrecy, and more losses, and thus, less mobility. They increased its invisibility by operating in small, light groups that made them hard to spot in rural areas and could conceal themselves in urban areas in the human terrain.

Using its military apparatus not for military victory but for political success, the PKK designed its military effort as a supplementary tool for its political campaign, shifting its aim from territorial separation through military victory to establishing a 'Democratic Confederalism', coercing Turkey into a negotiated settlement with a politico-military campaign. This was, in generic sense, aligned with its grand strategy of 'exhaustion' and 'costly signaling' as well as its military strategy of sensational and symbolic attacks with the use of more asymmetry that have been embraced upon its military defeat. In order to reach its renewed end-state of democratic autonomy (as termed by the pro-PKK entities), the PKK relied mostly on events organized by the KCK in the socio-political arena in a bottom-up approach and designed its military strategy as a supplementary tool.

Turkey's perception of stalemate and search for a political success through resolution

The PKK's search for politico-military success worked. Between 2006 and 2007, Turkish officials noted the inconclusiveness of the military effort to eradicate PKK violence or to reduce it down to margins. Therefore, having recognized the costly deadlock and the stalemate in 2007, Turkey engaged in a series of backchannel talks with the incarcerated PKK leader, Ocalan, and initiated meetings in Oslo with a PKK delegation, comprised of both the political leadership in Europe and military leadership from Qandil/Northern Iraq. Set against this background, the Turkish government officially commenced the Kurdish Opening and made its intention public in 2009. However, Turkey's peace attempt revealed many contradictory events despite a short-term unilateral ceasefire declared by the PKK. The state's progressive efforts to remove grievances and employ peaceful rhetoric were interrupted by the arrest of numerous civilian Kurds including lawyers, activists, and civil society members, as well as 53 members of the pro-PKK political party, Democratic Society Party (DTP). Arrests were made on the grounds of organic ties with the KCK, which under the Turkish law was deemed the legal equivalent of the PKK. Once the mutual confidence deteriorated between the conflict parties, Ocalan -through his attorney- commenced a new era called Strategic Lunge through the use of an all-out People's War strategy for developing de facto autonomy in the region, which made the break-off clearer in March 2010.

After intermittent fighting and the PKK's call for a cease-fire after in late 2012, the Turkish government explicitly commenced a new resolution process and started overt negotiations with the PKK through its incarcerated leader. These negotiations were publicly declared on March 2013 in a message from Ocalan during the Nevruz, which celebrates the arrival of Spring and is a symbolically important day for Kurds, in Diyarbakir, a metropolitan city densely populated by Kurds. The bilateral violence stopped with an informal cease-fire and a new negotiation period -The Resolution Process- commenced. Ocalan, in his message, underlined that the moment was ripe for a resolution to bring the violent conflict to an end through political action (a negotiated settlement) toward a democratic solution, vital to the Turkish and Kurdish societies ("Ocalan's letter on peace", 2013). Ocalan also made a call for a cease-fire and the withdrawal of the PKK's armed militants from Turkish soil. Only about 20 percent of the forces withdrew after the PKK's objection to the government's alleged inaction toward specific socio-political reforms, lack of a legal reassurance for the withdrawal, and the continuation of KCK arrests while the cease-fire continued. The withdrawal started in Spring 2013 but gradually stopped upon the fracture of the peace attempt. There are multiple reasons for the break-oft" of the second peace attempt, including the domestic political context, and the regional instability caused by the Syrian Civil War, among others -all beyond the scope of this study.

Because the second resolution was crippled in mid-July 2015, violence between the parties increased (shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3). Turkey reinstituted its intense securitization approach and its harsh anti-PKK state discourse, yielding high tensions and escalated violence, however, with a dramatic shift. The PKK changed its focus from a rural to an urban setting. As Duran Kalkan, one of the PKK's top council members, noted in his book "Rural-based urban guerrilla warfare,"4 the PKK shifted its focus from the physical to the human terrain (referring to the social and cultural aspects of an operational environment) in its new strategy. Based on its experience with its Syrian Democratic Union Party's (PYD) urban warfare against ISIS in Rojava (Northern Syria), the PKK started to employ urban guerrilla tactics and dug ditches and built barricades as part of their overall strategy of self-governance in Kurdish-populated towns (e.g., Diyarbakir-Sur and Silvan, Mardin-Nusaybin, Hakkari-Yüksekova, and §irnak-Cizre).

As shown in Figure 11, the PKK's attacks in urban areas far exceed its attacks in rural attacks, indicating the urbanization of PKK violence in this period (shaded area). Intense clashes produced a high death toll, and by mid-July 2015 and March 2016, security forces' casualties reached 355 (265 soldiers, 133 police, and 7 GKKs), while 285 civilians lost their lives (civilian casualties include attacks by the Islamic State).5 According to the International Crisis Group's open-source database (ICG, 2016), the figure for incapacitated PKK members since July 20, 2015 (until July 04, 2018) was 2,150, the civilian casualty was 452, and security force casualty was 1,092. Government figures, on the other hand, indicate that 3,583 PKK members were incapacitated, while another 602 were captured, and 574 surrendered in one year-until June 17, 2016 (Terror results for 265 days, 2016).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 11 Number of PKK-initiated attacks in rural versus urban areas (1984-2018).

These were Turkey's first attempts seeking success with a broader political campaign with sociological peace infrastructures (e.g., wise men commission) after a long-attached effort around the official motto of "until no terrorists remain." After its fracture, the conflict yielded more complications, mostly because Turkey's once purely intrastate conflict had recently become heavily regionalized and internationalized by the developments of the Syrian Civil War. In recent circumstances, understanding the dynamics of the Turkey-PKK clashes has become almost impossible without understanding the regional dynamics shaping the civil war in Syria, e.g., the U.S., Russia, and Iran's strategic vision in the region as evident with Turkey's two important cross-border MOPs in Syrian territory: Operation Euphrates Shield on August 24, 2016, and Operation Olive Branch, against the PKK-affiliated People's Protection Units (YPG) in the Syria/Afrin region.

Overall, the current situation indicates an escalated violence in and out of the Turkish territory, including PKK's long-attached sanctuary, Northern Iraq, and newly emerged Northern Syria (east of the Euphrates). Thus, the conflict is far from being resolved. Turkey's approach to the conflict indicates the sole usage of a securitization and containment paradigm by relying on the military, police, and GKK.

Discussion of victory and success

The TAF's military victory and the PKK's multi-dimensional strategy shift

As examined in the previous section, during the initial confrontation period of 1984-94, both parties sought unilateral military victory. In that period, the epicenter of the conflict was in the military domain with the focus on the territorial control of the critical region, namely, Turkey's eastern and southeastern regions (Ünal, 2016d). The character of the war in this phase was capacity-oriented; the parties fought to exterminate one another through annihilation and attrition. For Turkey, its state's territorial unity was at stake; it was about existence or survival for the PKK, meaning that their political end-states were decisively affecting one another.

Relying on the Maoist Theory of People's war, the PKK later pursued a top-down strategy to create an autonomous and united Kurdish state in the broader Middle Eastern region with territories comprised by Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. In its pursuit of military victory, the PKK employed a more direct challenge and conducted raids on remote military outposts to physically exterminate Turkish forces from the region. Moreover, as part of its initial Maoist strategy to enforce social mobilization from Kurdish peasantry, the PKK attacked non-conforming Kurds in the key region and conducted carnages, killing mostly village guards and their family members (Gürcan, 2015). Because of his belief in military victory and military focus, Ocalan rejected any political action and even affiliations with the newly emerged pro-PKK political parties in the early 1990s (Ünal, 2012b; 2016b).

Turkey's continuous updates on military doctrines in its military COIN efforts in the early 1990s clearly disrupted PKK insurrection and resulted in its military defeat, as acknowledged by Ocalan in 1993 and 94 (Ünal, 2016a; 2016b; 2012a). Acquiring the initiative in violent clashes, the TAF impeded the PKK's attempt to realize the third stage of the Maoist strategy, namely, strategic offensive, and negated the PKK's move to maintain the control of the land in the region (Ünal, 2016d).

After its military success over the PKK's initial military challenge, Turkey foresaw the demise of the PKK by mistakenly understanding the character of insurrection as static. However, a military defeat or victory in territorial control does not guarantee conflict termination in the best interest of the counterinsurgent. In most cases, initial military victory even drives a state's misperception of the developments. In those cases, states believe that the initial military victory over the territorial control of a region will lead the insurgent's demise and thus it is believed to be the biggest, the most important, and decisive step. Because of a misconception of the initial military victory, which is just a façade of a very complex problem, states fail to recognize the vitality of the socio-political and social psychological dimensions, as the very essence of an insurgency. Thus, states tend to fail in converting the military success into favorable results in political terms (Gürcan & Ünal, 2018) which, ultimately, results in sustained protracted wars with dramatic material and human cost adding different layers into already existent complexities (Taydas, 2006).

Most misconceptions about the initial military defeat of the lesser are related to the dominance of the military mindset in COIN campaigns. This error is mainly due to the domineering role of the army and army commanders as an actor(s) exerting and simultaneously gaining political power in COIN campaigns, particularly in its initial terms and periods (Gray, 2007). As Gray (2007) notes, it is difficult for army commanders to comprehend that the war they are pursuing is just an instrument to a specific political end state. The war they are fighting, argues Griffin (2014), should only be designed to set out the conditions for a political solution. In other terms, the insurgents do not constitute the sole and core of the problem in its entirety. The insurgents become of secondary importance when the first confrontation phase is completed, when they are militarily defeated by state forces and denied pursuit for territorial control in military combat (Ünal, 2016a; 2012b).

This emphasizes the role of asymmetric warfare on capacity and will over time. In exploiting asymmetry, insurgencies pragmatically shift to different military and political strategies in not only the tactical level (military dimension) but, at certain times, in the operational level (military and political dimension), and even in the grand strategic level (military, political, socio-political, and economic dimension), resulting in the insurgencies adaptation to newly emerged socio-political and security environment (Duyvesteyn, 2006). More importantly, the state's military (physical) defeat of a violent non-state actor (VNSA) in a direct revolutionary confrontation (learning point in credibility and capacity) would eventually lead the insurgent to act pragmatically by using every conceivable means (mostly terror) to survive and challenge the state actor asymmetrically and indirectly to attack its will to fight (Arreguin-Toft, 2001). As Isabelle Duyvesteyn (2006, p. 136) put it, "terrorism is the resort of an elite when conditions are not revolutionary" or, as Crenshaw (2007, pp. 24-26) noted, terrorism is the most indirect and asymmetrical method in war, mostly used when failed in other methods. Therefore, after experiencing capacity defeat on the battlefield, as a critical teaching moment, what becomes the primary objective for an insurgent is to survive and hurt the adversary by exhaustion (a.k.a. costly signaling).

However, most states misinterpret this critical juncture by thinking that such a military defeat would lead towards a total demise and eradication of the insurgent in subsequent terms; a different story begins to prevail at this point forward. Most states inevitably continue seeking decisive victory due to populist expectations in domestic politics, among other reasons. However, the military defeat of the inferior is the most critical juncture in the states' COIN efforts. Why powerful states fail in asymmetrical and irregular wars against inferior actor rests in this critical point. States fail to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses properly, and this is the very reason for their misconception of persistently seeking unilateral decisive victory (Arreguin-Toft, 2001). However, insurgencies -in their strategic communication- rely more on asymmetrical or indirect violence in which a states' kinetic, direct military COIN approaches remain insufficient and produce popular support from the related population in favor of insurgencies. As a result, the insurgents not only receive more sustainability and longevity, but the states become more political vulnerability due to a frustrated public or competing elites working to end insurrectionary violence. The Turkey-PKK conflict is an example.

The PKK's military defeat in 1993-94 is one of the most crucial breakpoints in the entire history of the conflict. It produced a dramatic change in the name of the character of the fight since the PKK, as the inferior, shifted to a bottom-up approach in which the political campaign started to lead its military effort, which, in essence, strongly reflects an asymmetrical nature. More specifically, the PKK negated the TAF's military superiority by switching to costly signaling in which the PKK aimed to signal its existence by terror attacks to hurt Turkey's socio-political stability and keep its threat on the Government's security agenda as the top issue -targeting Turkey's resolve and motivation to pursue securitization and unilateral victory- so Turkey would perceive the inconclusiveness of eradicating the PKK's ability to initiate violence (military stalemate) and thus seek a political compromise.

As analyzed in the previous section, the PKK, as an adaptive organism, like its insurgent counterpart, has easily and strategically adapted to the shifting socio-political environment. In many respects, the PKK's dramatic shifts have resulted in its four decades of solid resilience, proving Turkey's expectations wrong. That is, in such a conflict, a military defeat against an insurgent is not the end, but only the beginning of the story; this is evident in the PKK's prolonged survival and resilience, revealed in many different manifestations and representations over the four-decade conflict.

Ultimately, the PKK reshaped itself into emerging contingencies of social, political, diplomatic, and military contexts of the time. It modified its end-state twice, from secession to constitutional recognition between 2000 and 2005, and after that to democratic autonomy. By doing so, the PKK's political effort overweighed the military, focused on a political campaign complemented by military tools. After its failure to obtain international recognition in the European setting, the PKK started to apply a bottom-up approach (contrary to its top-down military effort in the initial years). Notably, with the creation of the KCK, in which its military objective was to make costly signaling to coerce Turkey into a negotiated settlement. Within this framework, the PKK shifted from attrition of the Turkish security forces to moral exhaustion of the governmental authority, targeting Turkey's will to fight by conducting reactionary and sensational terrorist attacks in both rural and urban settings. This was a more aligned structure given PKK's end-state(s), its grand strategy of out-administering through de facto socio-political events, and supplementing it with low-intensity terror attacks to undermine the government's will.

The PKK's will-oriented campaign to consolidate political compromise by employing low-intensity terrorist attacks to incur a costly signaling and aligned social events was reciprocated by Turkey. The state perceived the hurting stalemate that resulted with two consecutive resolution attempts in the succeeding phases. Overall, the PKK embraced new strategies to adapt to the shifting security environments and by employing the strategy of exhaustion (costly signaling), it managed to keep its threat level up and to remain at the forefront of the Government's agenda in hope to coerce the government to move towards a negotiated settlement.

In small wars, as in the Turkey-PKK conflict, the first military victory does not yield a clear-cut decisive victory even on the battlefield after a semi-confrontational guerilla fight. A military defeat of the VNSA/inferior/insurgent might not produce their total surrender, withdrawal or capitulation. Mostly, what they do is shift to more asymmetrical and indirect strategies once they acknowledge their military defeat in a direct fight against the state forces. Mandel calls this "limited victory" (2006, p. 29). Robert Mandel sees the difference between total and limited wars through the lenses of motives, strategy, and tactics. Total war requires decisive triumph in which the adversary is eliminated, extinguished, and vanquished, and the victor seeks dominance over the enemy by almost every means. Limited small wars, however, do not know such a victory. Thus, the state must resort to using military forces and diplomatic instruments in a grand strategic bargaining game to reach a more strategic victory encompassing political, social, economic, diplomatic, and psychological domains and make a positive impact on the adversary and related civilian population.

Limited war corollary entails the limited use of the military for directly related limited political aims that then require a subtler and comprehensive way of looking at victory and its strategic nature. The previous, because the enemy's destruction cannot be fully achieved because of the asymmetric nature of the conflict even in the initial (decisive, confrontational) phase. In subsequent phases of a conflict, this subtleness critically increases due to the shifts and moves of the inferior into other critical domains, determining the legitimacy and related popular support for the insurrection. These two main phases are the most important milestones of intrastate conflict, implying that the later phase is to be divorced from the military result by the winning states. In the second phase, a gradual transformation of the conflict into a non-violent dissent finally leads toward a meaningful concession culminated in a sustained peace via negotiated settlement as a viable and feasible exit strategy at both levels, individual and organizational. Therefore, the strategic victory -as called lately- entails the use of military triumph on a battlefield to be used as an instrument for durable post-war stability (Mandel, 2006). Strategic victory requires considerable time because the solutions to the political, social, and psychological ramifications of a conflict may take years after the military contest's finite ending (Albert & Luck, 1980, pp. 3, 5).

Given the two phases, prematurely assessing the outcome of war can be misleading. In most small war practices, states delve into the first phase and get caught up with its short-term results. War-winning has been pursued using unilateral military means, insisting incorrectly and paradoxically on the military solution as the sole resort to bring peaceful political results. Thus, the inevitable end state of a military win has led states' political aims to be governed by their military. More importantly, military win has been regarded as an end, not a means or instrument to an end (Mandel, 2006). In the end, victory does not happen upon one side's suppression or subversion of the other, even if the shooting stops briefly in the war-winning phase of a conflict. States have to think about the socio-political domains and plan carefully to use the military triumph in the socio-political context for an enduring peaceful end. Battlefield victories are never enough to eradicate an insurrection; they are just a turning point for the inferior party of the conflict to shift to an asymmetric and indirect fight to survive.

Who defines victory and based on what?

The concept of victory is contentious and inconclusive. Generally, the outcome of a conflict is mostly judged based on the outcome of what happened on the battlefield rather than its political, cultural, and psychological ramifications and factors (Johnson & Tierney, 2007, pp. 47-48). Johnson and Tierney (2006, p. 46) point out that the concept is heavily influenced by psychological and informational biases that make it open to perception and manipulation. Griffin succinctly concurs by stating that "[W]hat constitutes "victory" and who defines "victory" can remain fluid and this is especially true in COIN." The understanding of victory stems from pre-existing beliefs, certain symbolic events, and even more so, from manipulations used by the political or ruling elites and media. Popular support on either side is a determinant for the future of the conflict because it mirrors the perceived legitimacy of these actions. Legitimacy is again mostly based on perception and influenced by the psychology of war. What is critical in the perception of conflicts is that as Feaver and Gelpi (2005, p. 149) rightly note, the public is defeat phobic, not casualty phobic. Thus, the framing of the conflict in a particular way in the media and political discourses plays an important role. Johnson and Tierney (2007, p. 51) argue that two frameworks explain the perception of victory in conflicts, one is scorekeeping, and the other is match-fixing. While the former denotes victory by material gains and losses, such as casualties and territorial control, the latter, judges victory based on psychological and informational biases, irrespective of the concrete results on the battlefield. Scorekeeping is what states typically resort to in seeking popular support from mainstream society (not from the pro-insurgency strategic population) for their policies and countermeasures toward the conflict. The perception of victory is drawn by relying on social pressure, certain pre-existing mindsets, and symbolic events. Most coding measures on victory rely upon the military understanding of victory, which critically disregards how military outcomes are tied with or should be tied to politically advantageous results.

In other words, the focus is mostly on scorekeeping in casualties and frequency of violent events to gauge outcomes of conflicts and small wars. Jan Angstrom (2011) summarized the US perception of victory during the Bush administration and provides the following five measures of success: casualty figures, control of territory, frequency of terrorist acts, the spread of weapons of mass destruction, and spread of democracy. She argues that the United States Government has a somewhat ambivalent view of victory for the War on Terror campaign. The same ambivalence applies to the PKK case. The numbers of incapacitated insurgent members did not serve as a panacea to reduce the PKK insurrection, let alone eradicate it. As shown in Table 3, according to the official government figures, a total of 42,230 PKK armed militants have been incapacitated in one way or another (killed, injured, or captured) during the conflict (1984-2018); another 7,146 were surrendered to security forces. According to Angstrom (2011), state officials continue to brag about killed terrorists in official state jargon and reflect upon populist dictum, saying that the counterterrorism efforts will continue until no terrorist remain. "Until no terrorist remains" has turned into a motto in state officials' statements. As Feaver and Gelpi (2005) have rightfully noted, the public may display defeat phobia but not casualty phobia. In Griffin's (2014) words, states tend to embrace match-fixing or scorekeeping (headcount) rather than a meaningful determination of success based on a viable, comprehensive approach inclusive of social (popular support, such as vote casting), psychological (legitimacy), economic, and political indicators in their COIN efforts. The same is true for the Turkey-PKK conflict.

Table 3 Killed, injured, captured, and surrendered PKK members (1984-2018).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Additionally, when it comes to limited wars, victory rarely means the end of a conflict. Johnson and Tierney (2006) show how victory is far from being a clear-cut military outcome. They argue that determining a winner and loser of war is an important and, equally, straightforward query. However, choosing a winner and loser based on net losses and gains is not clear cut and conclusive issue; even more so in intra-state conflicts. As mentioned above, an insurgent might have been subject to a military defeat, but as time goes by, longevity works in its favor. An insurgent's resilience is an indication of a states' failure and, thus, the success of an insurgent despite its military defeat. The process in which immediate victory can turn into a defeat is the very reason for states to have a grand strategic campaign at a political level, covering different domains in which the military force is supposed to be used only as a tool (i.e., instrumentality of war) that is deployed discriminately, carefully and proportionately.

The assessment of a conflict's outcome is intricate for two reasons: one's understanding of when the conflict ends, and one's perception of the outcome are not univocal. Either short or long-term assessments could be problematic in assessing the outcome of the war. Orr (2003, p. 8) argues that wars develop and are won or lost in two phases. The first phase is the "military outcomes on the field of battle," the second phase happens "through reconstruction and reconciliation" after the battle. "What is won on the battlefield can be lost entirely thereafter if the countries attacked are not turned into better and safer places" (Orr, 2003, p. 8). Mandel (2006, p. 19) calls this first phase "war-winning"; he also calls it the confrontation (decisive) phase, in which parties to war strive to bring about a military conclusion to the war. Mandel names the next phase, "peace winning." While war-winning is mostly comprised of military effort that results in the destruction of the enemy's main forces and eliminating or considerably limiting the enemy's future war-making potentials. The previous entails a comprehensive approach including the political, social, economic, diplomatic, informational, and military domains of a conflict, which are related directly and indirectly, and important aspects to be sorted out for a strategic victory of peace winning. Turkey's peace attempt in the PKK conflict and its failure can be considered as a failure of "winning peace," neglecting the importance of a political conflict resolution after the initial military defeat. In other words, Turkey failed to convert its military defeat against the PKK into a political gain. What is more, disregarding the need for reconstruction and reconciliation following the successful first phase, did not only prevented a long-term resolution, it diminished the importance of the military win altogether. Violence and the number of casualties caused by the PKK (see Figure 10) reached peaking points several times (in 2007, 2011-2013, and 2015) after the declaration of the military victory. The critical understanding of all limited wars, so far, has been that winning a war does not earn winning the peace out of it. In these kinds of civil wars, winning war here denotes the victory in military terms, winning the peace is to be in political terms because winning the peace does not equate with the absence of war or violent strife (Duyvesteyn, 2006).

The dynamics of limited wars and military victory in an intra-state context

The assessment of victory is subjective. Particularity defines intra-state conflict. Insurgents are generally materially weaker than the state military power they are fighting. However, it has been noted that they are politically more determined, mainly because with the insurgency, their whole existence is at stake. In the home-grown small wars in an intra-state context, for the external power, the war is "limited." For the insurgent of the intra-state context, on the other hand, the war is "total." This explains the initial overreaction in the intra-state conflicts, the use of harsh military power, the leading role of the military in states' countering efforts and thus also forgetting or not tailing a political aim to the small wars in the intrastate context. What keeps states from being narrow-minded in seeking decisive military results in the first confrontation phase of small wars originates from this "total war" syndrome or the state's perceived threat of its existence. On the other hand, what explains the resilience of insurgents is the superior political will to fight or as Jeffrey Record notes (2007, p. 17) "the superior strength of commitment (...) [that] compensates for military inferiority." In the end, the outcome of war is and will never be as vital for the external state powers as it is for the insurgents and internal states targeted by the insurgents -within the intra-state context.

Temporality complicates the outcome of war even further. The longevity, resistance, and delay favor the weak because the guerrilla can win by simply not losing while the state can lose simply by not winning. Andrew Mack (1975), Ivan Arreguin-Toft (2001), and Gil Merom (2003) offer significant insights on how and why the superior loses to the inferior by underlining the dynamics of strategic interaction and the democratic states' vulnerability to carefully designed and adequately conducted irregular warfare. Jeffrey Record argues that the inferior's superior political resolve will not be enough by itself to win without substantial eternal support that would alter the power relations (2007, p. 22). While a decisive military victory might be possible within the confrontation phase by unilateral military means, the overall victory and success in small wars, particularly in the intrastate context, does not determine the outcome for the later phases. Because a victory is a subjective category, most decisive military victories seen and perceived at the time might result in failure later, as analyzed in the case of Turkey's prolonged struggle against the PKK and the PKK's decades of resilience.

As Carl von Clausewitz pointed out, the notion of victory is comprised of three main elements: "the enemy's greater loss of material strength, his loss of morale, [and] his open admission of the above by giving up his intentions" (1976, p. 277). The last one has become critical after the second World War when most wars have become limited. In these conflicts, the enemy has experienced the loss of material strength and morale in a direct confrontational fight, but they have never given up their intentions. Thus, Clausewitzian dictum of war as "an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will" (1976, p. 83) became more valid and the center of gravity about the nature of victory in winning small wars since the start of the twenty-first century. As the insurgents' focuses on diminishing the states' will to fight instead of their capacity, by exploiting all dimensions of asymmetric warfare and resorting to terror, this dictum implies that insurgents' will to fight is a strategic aim to serve a viable political end-state designated by the state. While the use of force remains the central element of the war-winning strategy, the decisive battlefield victory (which is the central issue for Clausewitz) is what has been changed.

Military triumph has had limited relevance for concluding wars and reaching victory in the process of winning peace for civil wars of the post-1945 period.

The perspective on the outcome affects the understanding of what happened just as much. Who is assessing, the state or the insurgent leader? Is it based on the perception of the state's public or the non-state actor's public? Or is the evaluation offered by outsiders as neutral representatives of the international community? The defeated party's perception is of particular importance because their support of the inferior determines the survival and longevity of the insurgency. The war is over when the defeated side accepts the loss and submits to the winner's demands. This requires the recognition of the military outcome in the battlefield and openness to internalize it at the socio-political level. However, Metz and Millen (2003) have recognized an enigma behind the process of the recognition of defeat. They suggest that insurgencies, unlike traditional adversaries, seek and perceive victory by surviving (avoiding defeat). This avoidance of defeat shifts the main context of the conflict from direct to indirect means and targets, from rural to rural-urban conflict, from pure military confrontation against guerrilla fighting to embracing terror as a method of conflict, and so forth (Mandel, 2006). This is what happened precisely concerning the PKK's prolonged resilience and survival in which, as previously analyzed, the characteristics of violence and the nature of the PKK has changed. While PKK violence was initially more direct, PKK attacks revealed more indirect targets given the location, target status, and type of incidents. Therefore, the PKK's resilience over four decades and its continuing ability to employ violence at a level to politically hurt the Turkish state's legitimate authority (monopoly of violence) can be considered a success despite its military defeat in the mid-90s. As a result, as Robert Mandel (2006, p. 17) notes, insurgents can "easily label military defeat as political victory - with credibility in the eyes of regional onlookers-as they can label terrorists as freedom fighters."

Understanding victory as a military solution to a conflict renders the concept too flexible and vague. Thus, as Carl von Clausewitz, underlines in many accounts, wars ought to be fought to achieve political goals. Victory now has to be split into two: one is "military (credibility and resolve)" being capacity-related and the other is political being (accommodation and exit path), related with the "will to fight." If, as Thomas C. Schelling (1980) argued, the concept of victory inadequately expresses what a nation wants from its military forces, the concept has to be rethought and possibly, as we propose in this paper, substituted with another more coherent concept. Success is proper in this context for three reasons. First of all, victory stops with the military win and does not mark the end of the conflict. Success, on the other hand, indicates not a military but a political solution to a political problem with social and psychological ramifications. Second of all, success is not subjective and one-sided. It shifts the perception from one-sided victory to a favorable outcome for all parties involved. Third of all, since outcomes in COIN, are inconclusive, not binary, simply a victory or a defeat, success, as an improved understanding of war outcomes, could enable more effective long-term conflict termination.

Conclusion

With the end of the cold war -and the onset of the new risks from global terrorism- policymakers and scholars must now consciously decide what it means to achieve victory, what level of military victory is desired, what changes victory should or must bring, and what costs of war are acceptable, both for the victor and the vanquished (Mandel, 2006). Another vital issue in intrastate conflicts is to clearly understand the insurgent's perception of victory in order to design sound responses with relevant strategies in political and military terms. The problem here is the one this paper is trying to address -the lack of a formal theory of victory and the absence of an analytical concept to operationalize it.

The accepted understanding of the concept defines victory as a momentum when (1) a loser's war-making military capability is dramatically eliminated; (2) the loser, as the vanquished party, accepts the terms that the victor imposes through a formal surrender agreement, and (3) the victor possesses the monopoly of use of force (armed strength) (Kecskemeti, 1958, p. 5). However, the classic notion of victory in contemporary small wars has been an exception rather than a rule. This is due to the changing nature and forms of these conflicts. In intra-state conflicts, it does not come to the coerced formal capitulation of the insurgents as a whole. After the military victory, the insurgents begin to go deeper underground, camouflage, and blend into a non-combatant civilian society by shifting the space of the conflict. They might start targeting symbolic and indirect targets to hurt the enemy's political vulnerabilities and engaging in socio-political activities by shifting the domain of the conflict. In so doing, the insurgent's main aim is to survive and sustain their campaign. At the same time, they provoke the state's overreaction to gain legitimacy for their cause and thus widen their support base. With the growing legitimacy, they gain popular support, both passive and active, as well as group solidarity and political resilience.

Therefore, the core notion of victory has changed, and with it, the current understanding of victory should shift towards the influence over the enemy. This change of the core notion of victory becomes evident in asymmetric wars between a state and an insurgency as a non-state actor, in which the stronger party (the state) as the winner in a contemporary battle fight needs to incur strategic effect to make or manipulate the insurgent to agree on a viable political end result. In short, for small intra-state wars, a classic notion of total victory fails, because military successes in intra-state conflicts do not result in formal surrender. The usage of the concept victory is thus not appropriate for either military or strategic wins.

This paper claims that the use of "success" is more proper in this context for three reasons. First of all, it indicates not a military but a political solution to a political problem with social and psychological ramifications despite its bitter manifestations in violence as an ostensible security problem.

Second, the use of victory in political discourses connotes a strong power relation between the two groups partaking in the process that defines one as a winner and the other as a loser. Because the main aim of COIN should be restoring governmental (legitimate) authority in the insurgent areas, labeling the end of the COIN campaign as a success, instead of victory, shifts the perception of the campaign from one-sided victory, designating the insurgents as losers, to a favorable outcome for all the parties involved.

Third, the outcome of a war in COIN is never a mutually exclusive binary, either victory or defeat. Once insurgencies resort to asymmetrical warfare and use terror as a method, the counterinsurgent shall have to understand it as a strategy used to produce and design a viable counter-strategy within a broader socio-political campaign and a meaningful end-state. As Angstrom (2011, p. 4) notes, improved understanding of war outcomes, particularly for small wars, could enable more effective war termination in the long run because a flawed and unsustainable peace would result in the recurrence of violence or a new war. Thus, states need to prioritize war termination strategically, executed as a success because this way, the termination is more likely to lead towards sustainable peace.