Introduction

Liver Cirrhosis (LC) marks an advanced phase of liver fibrosis, distinguished by the alteration of hepatic structure and the emergence of regenerative nodules. It serves as the ultimate common path for the majority of liver diseases, thus manifesting as a multifaceted chronic condition that contributes to mortality rates globally of about five to ten individuals per 100,000 annually1. In its advanced stages, LC is identified through the onset of clinical complications primarily due to portal hypertension and liver failure2. Presently, it stands as a significant public health issue, propelled by rising alcohol consumption, obesity rates, and viral hepatitis prevalence3. Medical advancements through controlled and randomized clinical trials have spotlighted numerous strategies to enhance patient prognosis, evidencing, for instance, the advantages of prophylactic actions against variceal bleeding4 and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)5. Similarly, there is an extensive array of preventive recommendations grounded in evidence, including hepatitis A and B vaccinations, alongside early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma6.

Individuals diagnosed with LC are advised to adhere to specific dietary guidelines, engage in a regimen of medications, undergo routine laboratory tests, and partake in frequent medical consultations. While health professionals are tasked with offering these recommendations, it fundamentally falls upon the patients to implement them, significantly impacting medication adherence, diet compliance, alcohol cessation, and medical follow-up. Consequently, successful cirrhosis management necessitates educating patients on the importance and methodology of these practices7.

Global health policies have underscored the necessity of formulating patient-centric services, positioning the patient at the forefront of service design and delivery8. To achieve this, optimizing patient involvement in their care management is imperative; services should cater to their needs and preferences, empower their decision-making, and furnish them with the requisite information to make informed choices9. Herein, the concept of “information need” is introduced, defined as “the awareness of insufficient knowledge to fulfill a specific objective within a given context or situation at a particular moment”10. It is acknowledged that fulfilling these information needs is essential for health care providers to deliver adequate patient education11.

Various research endeavors have explored the information needs associated with respiratory, metabolic, and cardiovascular conditions. However, investigations focusing on populations with chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis are relatively scarce12,13. Within this context, studies have revealed that patients with cirrhosis encounter a myriad of physical and psychosocial challenges, frequently reporting unmet needs across five pivotal areas: informational/educational, practical, physical, healthcare, and psychological support. Specifically, in the informational/educational domain, there are noted deficiencies in patients’ understanding of their illness, its progression, prognosis, the necessity for hepatocellular carcinoma screening, the linkage between cirrhosis and their experienced symptoms, alongside a notable lack of palliative care awareness and dissatisfaction with the communication skills of healthcare professionals14. Further analysis into the experiences, knowledge, and beliefs of individuals with chronic liver disease highlighted a significant information deficit regarding the etiology of their condition, available treatment options, symptomatology, and medical management, also underscoring substantial educational gaps15.

Acknowledging that insufficient disease awareness may amplify anxiety and the emotional toll of the condition, thereby adversely affecting the quality of life of these individuals, and recognizing that grasping patients’ concerns and needs is critical for crafting educational strategies aimed at enhancing clinical outcomes and healthcare models in line with patient expectations16, this study sets out to pinpoint the primary information needs of patients with hepatic cirrhosis in our region and their impact on quality of life.

Materials and methods

Study Design and Population

This study employed an observational, analytical cross-sectional design to assess patients diagnosed with liver cirrhosis at the Gastropack medical center’s outpatient hepatology service in Cartagena, 2021. Inclusion criteria encompassed individuals aged 18 and above with either a newly diagnosed or known case of liver cirrhosis, established through clinical, imaging, histological criteria, or elastography. Exclusions were made for pregnant individuals and those with severe cognitive impairments or hepatic encephalopathy.

To ascertain the information needs, focus groups comprising patients with a cirrhosis diagnosis (10 patients in each group) were formed. These groups were presented with four open-ended questions: What would you like to know about your liver condition? Which topics do you feel you are more informed about and why? Which topics do you feel less informed about and why? And what additional topics would you be interested in or require information on? This method aimed to further delineate the various subtopics under the principal information needs identified, allowing for the introduction of new subjects. A literature review was also conducted to identify potentially significant areas for patients.

The primary information needs unearthed during this initial phase included the causes of cirrhosis, signs and symptoms, decompensations/complications, disease progression/prognosis, pharmacological treatments, liver cancer, liver transplantation, nutrition, medical follow-ups, and lifestyle adjustments. Subsequently, through a telephone survey employing a questionnaire designed around the 10 identified needs, participants were asked to select and rank the top five needs on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 represented the least important and 5 the most crucial.

To assess the congruence between patients’ actual information needs and those perceived by healthcare professionals, the same questionnaire was administered to both groups with identical instructions. Furthermore, to gauge the patients’ perceived need for additional support services, they were provided with a list including: alcoholism management treatment, palliative care, psychological counseling, spiritual counseling, disease education, financial aid, home care, physical therapy, and nutritional support. They were instructed to select the three services they deemed most critical for priority access. This questionnaire was similarly applied to the healthcare professionals to understand their perspective.

For the purpose of evaluating the real utilization of support services by cirrhotic patients, they were asked to report their engagement with services such as psychology/psychiatry, nutrition, social work, and spiritual counseling over the three months preceding the interview. The participants’ quality of life was assessed during the telephone interview utilizing the SF36 version 2 quality of life survey (SF36V2).

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of quantitative variables was conducted using measures of central tendency appropriate to the variables’ distribution, employing the Shapiro-Wilk test for determination. Qualitative variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies. The chi-square test was utilized to identify sociodemographic, clinical, and historical factors associated with information needs. The relationship between information needs and quality of life in cirrhotic patients, as measured by the SF36V2 scale, was explored by comparing the mean SF36V2 scores between patients who identified this specific need as among their top five and those who did not. To examine the interplay between the utilization of support services, the perceived need for these services, and quality of life, SF36V2 scores were compared based on reported service use and perceived access need. The Mann-Whitney U test was employed for SF36V2 score comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. The statistical analysis was conducted using Stata software version 16.0.

Results

The study included 107 patients with liver cirrhosis, with a median age of 63 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 54-73). Female participants constituted 53.3% (n=57) of the study population. The most prevalent educational attainment was completion of secondary school, reported by 34.6% (n=32) of participants. The majority, 60.8% (n=65), were married.

The comorbidity most commonly reported was overweight/obesity/dyslipidemia, followed by arterial hypertension (HTA) at 36.5% (n=39), and diabetes mellitus (DM) at 27.1% (n=29). Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) emerged as the most frequent etiology of cirrhosis at 28.9% (n=31), with viral etiology following at 26.2% (n=28). A significant portion of patients, 38.3% (n=41), reported being diagnosed more than 36 months ago. Overweight or obesity was noted in 56.1% (n=60) of patients. A majority, 80.4% (n=86), were in a compensated phase (Child-Pugh A), and 19.6% (n=21) were in stage B. Detailed characteristics of the clinical and sociodemographic profile of the sample are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Sociodemographic Variables and Information Needs in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

*p < 0,005. IQR: Interquartile Range. Author’s own research.

Table 2 Clinical Variables, Medical History, and Information Needs of Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

BMI: Body Mass Index; IQR: Interquartile Range; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Author’s own research.

The top five information priorities identified by patients include decompensations/complications (76.6%), disease progression/prognosis (71.0%), pharmacological treatment options (63.6%), liver cancer risk (53.3%), and the necessity for liver transplantation (42.9%) as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3 Quality of Life and Information Needs in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

| Variable | Total n = 107 | Decompensations/Complications | p | Progression/Prognosis | p | Pharmacological Treatment | p | Liver Cancer | p | Liver Transplant | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of Life, Median (IQR) | Yes n = 82 | No n = 25 | Yes n = 76 | No n = 31 | Yes n = 68 | No n = 39 | Yes n = 57 | No n = 50 | Yes n = 46 | No n = 61 | ||||||

| Physical Role | 50 (25-100) | 50 (25-100) | 75 (25-100) | 0.456 | 50 (25-100) | 75 (25-100) | 0.815 | 50 (25-100) | 75 (25-100) | 0.564 | 50 (25-100) | 50 (25-100) | 0.776 | 50 (0-100) | 50 (25-100) | 0.311 |

| Emotional Role | 66 (33-100) | 66 (33-100) | 66 (33-100) | 0.818 | 83 (33-100) | 66 (33-100) | 0.713 | 66 (33-100) | 100 (33-100) | 0.233 | 100 (33-100) | 66 (33-100) | 0.240 | 66 (33-100) | 66 (33-100) | 0.792 |

| Energy/Fatigue | 65 (45-85) | 65 (45-85) | 70 (55-80) | 0.879 | 62.5 (45-85) | 70 (50-85) | 0.515 | 57.5 (45-85) | 70 (55-85) | 0.198 | 70 (45 -85) | 60 (45-85) | 0.821 | 65 (45-85) | 65 (45-85) | 0.625 |

| Emotional Well-Being | 76 (56-88) | 68 (52-88) | 76 (60-84) | 0.559 | 68 (52-84) | 76 (56 -88) | 0.350 | 66 (52-88) | 80 (60-84) | 0.533 | 76 (52-84) | 70 (56-88) | 0.880 | 76 (52-84) | 72 (56-88) | 0.517 |

| Social Function | 75 (50-87) | 62 (50-87) | 75 (50-87) | 0.717 | 68.5 (50-87) | 75 (50 -87) | 0.407 | 62 (50-87) | 75 (50-87) | 0.486 | 75 (50-87) | 75 (50-87) | 0.619 | 75 (50-87) | 62 (50-87) | 0.771 |

| Pain | 77 (67-90) | 77 (57-100) | 77 (67-77) | 0.579 | 77 (55-95) | 77 (67-77) | 0.678 | 77 (55-95) | 77 (67-90) | 0.516 | 77 (67-90) | 77 (67-90) | 0.972 | 77 (57-90) | 77 (67-90) | 0.796 |

| General Health | 50 (30-80) | 42.5 (30-80) | 60 (30-75) | 0.891 | 45 (30-77.5) | 65 (35-80) | 0.359 | 45 (30-75) | 60 (30-80) | 0.547 | 45 (30-75) | 51.5 (35-80) | 0.775 | 42.5 (30-75) | 55 (35-80) | 0.374 |

| Change in Health Status | 50 (25-75) | 50 (25-75) | 50 (25-75) | 0.386 | 50 (25-75) | 50 (25-62.5) | 0.035* | 50 (25-75) | 60 (30-80) | 0.367 | 50 (25-75) | 50 (25-75) | 0.833 | 50 (25-75) | 50 (25-75) | 0.803 |

*p < 0,005. IQR: Interquartile Range. Author’s own research.

Factors Associated with Information Needs

In exploring factors associated with information needs, it was found that concerns regarding pharmacological treatments were predominantly noted among patients aged 61 to 80 years (p = 0.044), females (p < 0.01), and those who are married (p = 0.02). Conversely, these needs were less pronounced among patients suffering from kidney disease (p = 0.008) and those with alcohol-induced cirrhosis (p = 0.001). Information needs centered around liver cancer and the prospect of liver transplantation appeared more frequently among males (p = 0.013 and p = 0.011, respectively), patients with a viral or NASH etiology (p = 0.025 and p = 0.019, respectively), and were notably less common among individuals with obesity or overweight (p < 0.001). The desire for information on liver transplantation was especially prevalent among those with autoimmune conditions (p = 0.046) and a higher BMI (p = 0.022). Meanwhile, the demand for insights into disease progression/prognosis was particularly high among those with a viral etiology (p = 0.046), as outlined in Tables 1 and 2.

Relationship Between Information Needs, Support Services, and Quality of Life

The relationship between information needs, support services, and quality of life reveals a significant link between the SF36V2’s health status change domain and the quest for knowledge on disease progression and prognosis. Patients emphasizing this informational need scored higher compared to their counterparts who did not view it as crucial (p = 0.035), as illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4 Utilization of Services, Access to Support Services, and Quality of Life as Evaluated by the SF-36 Scale among Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

*p < 0,005. IQR: Interquartile Range. Author’s own research.

A total of 48.6% (n = 52) of the participants reported using a support service in the three months prior to the survey. The service most frequently utilized was psychology, reported by 59.8% (n = 64), followed by nutritional counseling at 53.3% (n = 57). Utilization of psychiatry/psychology services was linked to a decline in quality of life across various SF36V2 subscales, with lower scores noted for emotional well-being (p = 0.002), social function (p = 0.031), pain (p = 0.005), general health (p = 0.005), and changes in health status (p = 0.009) among this group.

An analysis of the association between perceived need for certain support services revealed a correlation between the lack of perceived need for palliative care access and higher scores across physical function, physical role, emotional role, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social function, pain, general health, and changes in health status (p < 0.001 for all variables). Conversely, patients who deemed access to educational services a priority scored higher in physical function and physical role (p = 0.041 and p = 0.003, respectively) compared to those who did not prioritize it.

Patients who prioritized access to physical therapy services reported higher physical function (p = 0.047), whereas those who emphasized access to nutrition services achieved higher scores in physical function (p = 0.019), physical role (p = 0.008), energy/fatigue (p = 0.014), emotional well-being (p = 0.005), social function (p = 0.003), pain (p = 0.026), general health (p = 0.006), and changes in health status (p = 0.033).

Information Needs as Perceived by Healthcare Personnel

Among the healthcare personnel surveyed, 28.0% (n = 14) were internists; 24.0% (n = 12), general practitioners; 14.0%, hepatologists (n = 7); with gastroenterologists, surgeons, or staff from other specialties making up 20% of the sample (n = 10), and the remaining 20% were nurses, nutritionists, and other paramedical professionals. The service area most commonly associated with their work was hospitalization, at 86.0% (n = 43), followed by outpatient services, at 62.0% (n = 31).

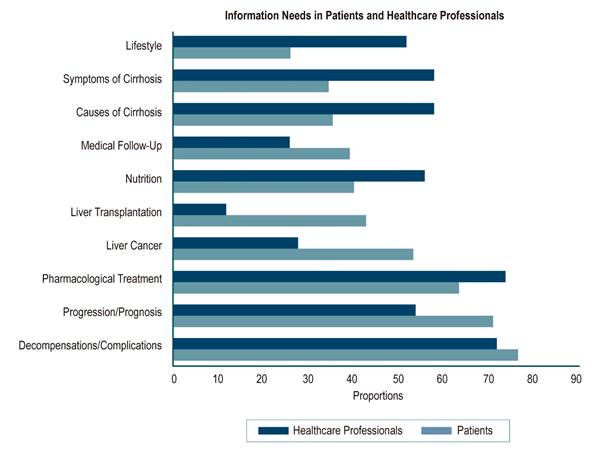

The healthcare professionals prioritized information needs around the indications and side effects of pharmacological treatments (74.0%), decompensations/complications (72.0%), causes and symptoms of cirrhosis (58.0% for both), and lifestyle information (52.0%) (Table 3). Support services identified as priorities by healthcare professionals included nutrition (64.0%), assistance for patients with alcohol addiction (52.0%), psychology (52.0%), and home care (38.0%).

Focus Groups

During focus group discussions, participants voiced concerns about various complications that could occur as their disease progressed, how to prevent disease progression, and the different stages of cirrhosis. Regarding pharmacological treatments, they expressed a need for information on whether a specific treatment for cirrhosis exists and had questions about medications they should avoid or that might exacerbate their condition. They were keen to understand at which stage they would need to consider a liver transplant and the procedure to access such a treatment. Furthermore, while many participants acknowledged receiving adequate information on nutritional recommendations, they felt these guidelines were not sufficiently clear and suggested the integration of a nutrition professional into their routine medical follow-up. The etiology of their disease remained unclear to some participants, who expressed a desire for more detailed information. Among the additional topics of interest, information needs relating to COVID-19/cirrhosis emerged, specifically concerning the relevance and adverse effects of vaccination for the virus and the risk of complications should they contract the infection.

Discussion

The demographic composition of this study aligns with previous research conducted in Colombia on patients with cirrhosis17-20, providing a consistent epidemiological backdrop. Among the cirrhosis patients studied, the foremost informational need revolved around the decompensations and complications associated with the disease. This was followed by concerns over disease progression and prognosis, details on specific pharmacological treatments and their side effects, the risk of liver cancer, and the necessity for liver transplantation. These findings mirror those of an Australian cohort21, where a significant emphasis was placed on understanding liver cancer and disease prognosis.

Patients with a viral cause for their LC expressed a heightened demand for information pertaining to liver cancer and the progression/prognosis of their condition. This contrasts with findings from Chen and colleagues, whose research focused on evaluating educational needs, who noted a predominant interest in the side effects of antiviral treatments among patients with chronic viral hepatitis22. The divergence could be attributed to the limited number of patients undergoing antiviral treatment within our cohort, suggesting that information on this subject might bear lesser significance for them.

A notable observation was that patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) as a comorbidity demonstrated a diminished interest in pharmacological treatment information. This could be explained by the early stage of liver disease and infrequent decompensations in this patient subgroup, making pharmacological interventions less pertinent compared to the management of renal conditions. Additionally, among patients with an alcoholic etiology, there was an apparent disinterest in treatment-related information, highlighting a potential area of concern for ensuring compliance and effective management of LC. Demographically, patients over 60, males, and those who were married reported a greater need for information on pharmacological treatments. All of the above underscores the importance of tailoring educational initiatives on LC to accommodate varying information needs based on cirrhosis etiology, comorbidities, and age.

Furthermore, our study uncovered an association between the desire for information on the disease’s progression and prognosis and an improved quality of life, particularly in the domain of health status changes as measured by the SF36V2. This finding diverges from prior studies which identified a negative correlation between the need for educational and support services and quality of life metrics23-25. This discrepancy may reflect a proactive interest among patients predominantly in the compensated stage of cirrhosis in averting further complications.

In our study, we were able to ascertain the utilization of health support services, which constitute integral components for managing patients with LC comprehensively. Among these, the most frequently accessed service was that of psychology/psychiatry, closely followed by nutrition, aligning with findings from prior research14,21. Moreover, our investigation demonstrates a correlation between the utilization of psychiatry services in the preceding three months and a diminished quality of life, particularly evident in emotional well-being, social function, pain, general health, and changes in health status.

An additional contribution of our study lies in evaluating patients’ needs regarding access to these support services and their impact on quality of life, a dimension heretofore unexplored in extant literature. Notably, participants prioritizing access to educational, nutritional, or physical therapy services exhibited elevated quality of life scores. This observation may suggest a heightened commitment to self-care and an increased awareness of their role in mitigating disease progression.

This study additionally appraised the viewpoint of healthcare professionals regarding the information needs of patients with LC. For these professionals, the most commonly identified information need pertained to pharmacological treatment, which was followed by decompensations/complications, the causes and symptoms of cirrhosis, and advice on lifestyle. These discrepancies may lead to gaps between the patients’ actual information needs and what is provided during healthcare interactions, potentially resulting in a lack of disease comprehension, poor adherence to treatment, and neglect of medical recommendations (see Table 5 and Figure 1).

Table 5 Information Needs in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis and Healthcare Professionals

| Importance of Information Variables | Patients n (%) | Healthcare Professionals n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Decompensations/complications | 82 (76.6)* | 36 (72.0)* |

| Progression/prognosis | 76 (71.0)* | 27 (54.0) |

| Pharmacological treatment | 68 (63.6)* | 37 (74.0)* |

| Liver cancer | 57 (53.3)* | 14 (28.0) |

| Liver transplantation | 46 (42.9)* | 6 (12.0) |

| Nutrition | 43 (40.2) | 28 (56.0) |

| Medical follow-up | 42 (39.3) | 13 (26.0) |

| Causes of cirrhosis | 38 (35.5) | 29 (58.0)* |

| Symptoms of cirrhosis | 37 (34.6) | 29 (58.0)* |

| Lifestyle | 28 (26.2) | 26 (52.0)* |

*Five variables classified as of the highest importance by both patients and healthcare professionals. Author’s own research.

Author’s own research.

Figure 1 Comparison of Information Needs in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis and Healthcare Professionals.

In addition to other methods, our study utilized focus groups, a qualitative technique that facilitates a deeper understanding of the experiences and beliefs of participants26. Researchers such as Burnham and colleagues in 2014 previously applied focus groups to patients with chronic liver disease and elicited discussions encompassing lifestyle, the lack of knowledge about chronic liver disease, adverse attitudes/emotions, stigma, healthcare access issues and high costs, and substance abuse. Participants in their study identified a knowledge gap as a critical element in their perception of disease prevention, risks, causes, and management15. Our investigation, through this methodology, garnered more nuanced insight into the specific sub-topics of information needs and also brought to light a newly identified need for information concerning COVID-19 infection in conjunction with cirrhosis.

Conclusions

The primary information needs discerned among patients with LC pertain to decompensations/complications, progression and prognosis of the condition, pharmacological treatment, liver cancer, and the requirements for liver transplantation. These information requirements are subject to variation based on the disease’s etiology, comorbidities present, and demographic factors like sex and age.

A correlation was observed between the need for information about disease progression and prognosis, a lack of need for palliative care, prioritization of access to educational and nutritional services, and enhanced quality of life. In contrast, utilizing psychiatry/psychology services was associated with a reduction in quality of life across multiple dimensions of the SF36V2.

The detail afforded by focus group interviews augmented our understanding of the information needs identified. Discussions frequently returned to topics such as potential complications, preventative strategies for halting disease progression, nutritional therapy, and specifics regarding the appropriate juncture and procedural considerations for liver transplantation.

The study also highlighted discrepancies between the information needs as perceived by healthcare professionals and those articulated by patients, potentially leading to a diminished grasp of the disease and adherence to treatment regimens.

texto em

texto em