Acknowledging: A Thread to Our Selves

Have you ever felt fragmented, isolated, silenced? We have. Decisions made and relationships held within and outside academia have placed us at odds with who we are and who we want to become. Academia has played its part. As undergraduate and graduate English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students we have been exposed to research and academic training processes where objectivity and neutrality are promoted in order to join scholarly conversations. Furthermore, as researchers, we are expected to mostly engage in academic writing and theorizing practices that favor western educational practices where the emotional and spiritual dimensions are not usually incorporated. However, approaching critical-feminist-decolonial theories have offered a venue for us to re-signify who we are and what we do.

Critical and Indigenous scholars and Feminists, including Chicanx/Latinx, discuss the issues of centralizing Eurocentric knowledge. On one hand, the practice of legitimizing one way of knowing (the Western way, mostly) is mainly characterized by being objective and accurate and is equated to the representation of a superior universalizing truth (Trujillo, 1998). This automatically displaces/excludes other ways of knowing that emerge from non-western cosmologies, ontologies, and epistemologies. In other words, knowledge is, most of the time, conceived as the transmission of information to train a skilled workforce that may sustain the industrial society rather than as a social practice (Svalastog, et al., 2021).

Likewise, Feminists and Indigenous scholars argue that “the education system has attempted the epistemicide of subjective and contextual Knowledge in its quest to objectify and make universal truth” (Svalastog, et al., 2021, p. 2). In order to move away from that colonial agenda, these scholars highlight that “life and knowledge are intertwined [therefore] knowledge has walked with us all our lives” (Svalastog, et al., 2021, p. 13). In this light, as critical-decolonized/ing scholars, we resonate with Chicana Feminists who honor ancestral-intergenerational knowledges we carry in our flesh, blood, and bones as part of our ways of knowing ourselves and the worlds and spaces we occupy. This posture in relation to what knowledge is, where it originates and resides, and how it is meant to make sense or be used/applied is part of the decolonial agenda we embrace.

On the other hand, for critical and feminist scholars, adhering to standards of excellence subscribed to a Eurocentric perspective constitutes a colonial canon in the sense that it promotes the formation of dehumanized, detached, and dispassionate scholars (Freire, 1996; Trujillo, 1998; Darder, 2011). Coloniality manifests in various ways in academia through philosophies, discourses, and principles that tend to homogenize individuals and practices. Homogenization implies disregarding stories, histories, epistemologies, and cosmologies that are fundamentals in the construction of individuals’ identities, without which we are censured (Pérez, 1999, p. 89). Thus, deeply rooted in academic colonial agendas is dehumanization that generates a sense of loss and fragmentation when privileging the cognitive dimension over the bodily and spiritual ones.

An academic dynamic that circles around the universality of conocimiento (knowledge) and is not open to contextualized saberes (ancestral knowledges) that emerge from communal lived experiences and people’s bodymindspirit(s) (Facio & Lara, 2014) leave profound wounds hard to reconcile when it comes to configuring one’s identities. Maestra Anzaldúa illustrates in the following verses how wounding may impact an individual: “I have been ripped wide open/ by a word, a look, a gesture-/from self, kin, and stranger” (Anzaldúa, 2009, lines 1-3)

We felt fragmented when we heard that we were not good enough as EFL learners, when surviving in academia entailed competing with our peers, and when the “only important aspect of our identity was whether or not our minds functioned” (hooks, 2014, p. 16). We also felt fragmented when research was presented to us just as a graduation requirement. Similarly, we felt so when the research topics were not of our interest but responded to other agendas like studying what is on trend or what was of interest to our advisors. We felt fragmented when we were not listened to and were reminded to conduct research without engaging in community work. Likewise, in developing our professional identities, there was pressure to become the native-like speaker and language expert without thinking communally or enhancing social justice agendas. We have felt fragmented with the ongoing debate of the soft vs hard sciences, being pushed to justify the importance of qualitative research. Finally, we have felt that way when for being considered a good academic or expert is mostly associated with fulfilling the categorization criteria proposed by the Colombian Ministry of Science (former Colciencias). Rankings have developed a citation dynamic that makes us wonder what the goal of research is, how it is contributing to the betterment of communities, and how we can do teaching and research that matters beyond rankings. These questions will not be solved in this paper but are posed for further discussion and inquiry.

In this article, we present the results of a four-year critical community ethnographic study (2018-2021) where we explore how our personal and professional identities have evolved and informed our positionalities as a result of partaking in undergrad and graduate courses that promoted critical decolonial methodologies. In doing so, we consider our training experiences in the EFL field, being aware of the complexities of configuring one’s identities, and wanting to offer an alternative to embrace teaching and research in EFL. We also discuss how those identities and positionalities have informed our philosophies of teaching/being/researching, i.e., how we see ourselves mediate relationships we hold with/in/beyond academia (teaching, research, writing, community work, personal development). This paper speaks to these experiences while exploring a decolonial academic writing process.

Decolonizing writing invites to re-evaluate top-down, audit-cultural assumptions where forced-choice categories (design, methodology, findings) are meant to be fulfilled in order for a work to be welcomed by publishers (Rinehart & Earl, 2016). These forced categories limit authors’ possibilities to express without necessarily having to justify and/or explain decisions made in terms e.g., of how to name a paper section or introducing testimonios as epistemological sites themselves without further analysis. We experienced these challenges in writing this paper and as authors we reconciled evaluator’s views and our interest in tuning-up our academic voices in non-conventional ways through word and images.

In this paper, the metaphor of weaving speaks to the embodied-visceral practice of raising awareness and acquiring tools to acknowledge, reconcile-understand, be-create, become, transform, dialogue, and walk. Acknowledging means welcoming and honoring the paths we have walked; it entails engaging in dialogue where no absolute truths are to be held. Thus, we welcome ourselves into this space of dialogue, reflect ion, and co-construction of understandings.

In sum, this paper offers elements to consider non-western ontologies that may inform the positionality and identity construction processes of EFL pre/in-service teacher-researchers who may want to stand on critical decolonial grounds. Furthermore, it introduces the pedagogy of possibilities (Carvajal Medina, 2020) as an alternative to decolonizing the Self and EFL/ESL teaching. It also presents lived experiences, testimonios, and art-creations as epistemic sites. Moreover, it proposes community research methodologies such as critical autoethnography and data analysis methods (e.g., theoretical coding) as ways of expanding the methodologies used in EFL and TESOL in Colombia. We hope you enjoy this journey! Welcome to this space of experience-sharing, dialogue, and mutual recognition!

Reconciling Tensions, Entering, and Exploring Decolonial Grounds

The colonial agenda has impacted territories not only by occupying land but also by unrooting people from ancestral knowledges and traditions. Thus, not solely territories and knowledges but also bodies have been colonized. The two sections Understanding offer, on one hand, a view on how colonialism may generally operate in academia mostly in relation to dehumanizing practices and identity construction processes; on the other hand, we discuss how coloniality may manifest in ELT’s linguistic, pedagogical, and curricular practices.

Understanding: A Thread to Colonizing/Decolonizing Practices in Academia

Usurpation, murder, enslavement, cultural appropriation, and dehumanization are some of the mechanisms of imperialist colonizing agendas sustained, in part, by research and teaching-education practices. Positivist views of objectivity and neutrality are still latent in research and academia. In the 21st-century neocolonial research condition (Carvajal Medina, 2017), the researchers’ cognitive dimension is privileged over their bodily and spiritual dimensions. Similarly, the researched is approached as an object of study that can be dissected for the sake of publishing objective-methodologically well-crafted studies in well-ranked journals. For indigenous peoples, research is “one of the dirtiest words in indigenous world’s vocabulary” since it has sustained a colonizing agenda that objectifies and dehumanizes (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012, p. 1). (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012 ) argues that “[h]istory was the story of people who were regarded as fully human” (p. 33). Therefore, misrepresentation of indigenous peoples and the erasure of their histories urge them to fight for land sovereignty, promote language revitalization, and tell their stories as resistance tools (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012,).

Evaluating the epistemologies, axiologies, and ontologies that inform colonized-dehumanizing research/teaching practices is paramount to switching the colonizing gears. Colonialism is sustained when we reproduce socio-political and economic systems that hierarchically place citizens in subordinated categories. Such systems and the binary rhetoric that informs individual and national identities constructions add up to the dehumanizing logic of colonialism. Morally deviant beings that do not ascribe to the values on which a nation is built are categorized as second-class citizens meant to be societally stigmatized and rejected. However, the study on the experience of the U.S. rural houseless, for instance, deconstructs the idea of the American Dream that speaks to a virtuous citizen who works hard to succeed and questions who, how, and under what circumstances can the dream be achieved (Carvajal Medina, 2017).

In turning the gaze away from a pathologizing view of the houseless, the researcher questions the institutional responsibility in perpetuating poverty and oppression and argues that labels are building blocks or discursive constructions that nurture imaginaries about the other and shape behaviors-attitudes, prejudices, and assumptions creating an abyss between us, the virtuous-good citizen, and them, the deviant other (Carvajal Medina, 2017, p. 38). Thus, critical-decolonial research may serve to dignify both the researched and researcher and offer a nuanced analysis to deconstruct institutionalized imaginaries and analyze how systems of oppression operate and sustain.

In terms of education, although the mission of institutions may claim to promote holistic education, we (students, teachers, administrators) “are expected to leave our personal lives out of our ‘intellectual’ workspaces” (Ayala, et al., 2006, p. 261). The capitalist notion of productivity positioned as the end goal of higher education institutions, very often, diverts attention from generating welcoming environments to embrace our whole beings and lived experiences, develop understandings, and co-construct knowledges. We, therefore, tend to forget that “feeling, living, breathing, thinking humans” (Wilson, p. 2008, p. 56) occupy educational settings. In favoring an individual’s cognitive development solely, education stands on colonizing grounds that lead to the dissociation of the self, causing feelings of isolation and fragmentation (Hooks, 1994; Ayala, et al., 2006). Disregarding the bodily and spiritual dimensions as part of the teaching-learning-research process is part of colonizing-dehumanizing agendas that influence the configuration of identities that center on ego, competition, and individualism. How may then, within this institutional landscape, EFL pre/in-service teachers shape meaningful and contextualized philosophies of teaching and research agendas? What are the values under which such philosophies and agendas are constructed and implemented?

Understanding: A Thread to Colonizing Practices in ELT and Some of its Tensions

What does social justice have to do with me? Social justice is the responsibility of the government (Student I, 23rd October, 2018).

The field of English Teaching has been characterized by referring to multiculturalism, criticality, and diversity as constructs an EFL/ESL educator is to know. However, the excerpt above, among others, illustrates how challenging it may be to not only name these concepts but also to understand them and use them pedagogically, and even embody them.

Eurocentric views have influenced English Language Teaching (ELT) in terms of the positioning of the field, professional identity formation, and linguistic policies. ELT is “a field of work wherein membership is based on entry requirements and standards” (Richards, 2008 as cited in Torres-Rocha, 2019, p. 154) where the ideal English teacher is a native speaker that represents Western culture (Holliday, 2005; Phillipson, 1992) qualifying them to methodologically be more effective in terms of language teaching. This belief usually generates a sense of inferiority and puts into question non-native English-speaking teachers (NNESTS), who configure their identities to respond to global market needs (Jenkins, 2005; Park, 2012 as cited in Torres-Rocha, 2019; Ortega, 2020). Therefore, language teachers’ professional identity revolves around achieving a native-like status.

Colonial ideologies have also limited teachers’ agency and view of professional development and identity construction (Granados, 2016). In this vein, Ubaque-Casallas (2021) states that the colonial construction of the ELT classroom generates a subalternization of knowledge and ways of being that affects how teachers make sense of their teaching. In the landscape of an ELT field where colonial roots that “repress other ways of being and doing” (Ubaque- Casallas, 2021, p. 209) are still latent, the author highlights the need to continue exploring pedagogies that enable teachers to reclaim their agency. Language teacher identity (LTI) is to be further studied considering that identity is a continuous construction mediated by time, space, experiences, and understandings developed, among other conditions. It is an important task because “looking at competing constructions of identity in language classrooms is perhaps one way to problematize practice” (Miller, 2007, as cited in Castañeda-Peña, 2018, p. 25). Interrogating EFL/ESL teachers’ identities construction permits discussing how colonial mechanisms are still present in academia and the alternative ways to resist the dehumanization of the self.

Additionally, language teacher education programs in Colombia face other challenges vis-à-vis coloniality. A case in point is moving beyond decontextualized and theoretical educational models, mostly informed by foreign standards, that do not reflect the reality of the classroom (Buendía-Arias, et al., 2020) and do not account for the socio-cultural particularities of the urban and rural settings (Usma & Peláez, 2017). Another challenge is developing curricula and syllabi that incorporate peacebuilding and social justice agendas to form leaders and active- solidary-responsible citizens that contribute to the betterment of economic, social, and cultural challenges (Serrano, 2008; Franco-Serrano, 2010; Carvajal Medina, 2020; Ortega, 2020). Other demanding tasks for such programs are: responding to the pedagogical (Torres-Rocha, 2019), linguistic (Buendía-Arias, et al., 2020; Henao Mejía, 2020) and self colonialism (Carvajal Medina, 2020), among others. The latter are addressed below.

Pedagogical and curricular colonialism is associated with the adoption of foreign theories and methodologies (e.g., communicative language teaching, CLT) without putting them into conversation with local knowledges, experiences, and realities. (Torres-Rocha, 2019) analyzes how the size of groups, the lack of access to adequate physical and material conditions, and the lack of sensibility to the socio-cultural reality make CLT an inappropriate method for contexts like Colombia. (Torres-Rocha, 2019) argues that “CLT, task-based approach, or content-based learning has not been easily adaptable to diverse settings, or teachers do not have a sense of plausibility for these methods in several local contexts” (p. 158). Thus, there is a need to make culturally relevant curricular adjustments in EFL in Colombia.

Linguistic colonialism deals with the status given to a language in comparison to others and how that status is reinforced through policymaking. In many developing countries, teaching English as a foreign language is prioritized due to the superiority ascribed to the culture it represents and the role language plays within the socio-economic, political, and communication sectors (Salinas, 2017; Phillipson, 2009). Such linguistic imperialism manifests in the reproduction or emulation of a foreign culture by neglecting local cultures and the generation of policies that are not culturally relevant. In the Colombian case, language policymaking is characterized by responding to Eurocentric, capitalist, oppressive, colonial top-down approaches (Henao Mejía, 2020). Consequently, these policies ascribe to productive and social classification logics that neglect the existence of the linguistic and ethnic diversity of the country and hinder the development of interculturalism (Bonilla & Cruz-Arcila, 2014; Guerrero, 2009; Henao Mejía, 2020).

Therefore, “the Colombian ELT community requires an epistemic turn” (Fandiño, 2021, p. 67) where language policies account for the linguistic and cultural diversity and realities of communities. Educational institutions are invited to consider including indigenous languages in curricula and pedagogical practices, re-signifying celebrations like the language day, creating programs and offering platforms to appreciate/acknowledge/respect the socio-linguistic diversity of the nation, and further exploring what interculturalism and multiculturalism may entail as living practices.

Practices/processes that constrain or limit an individual’s opportunity to be in and with the world favor Self colonialism. Anzaldúa (2000) argues that “when you take a person and divide her up, you disempower her” (p. 11). Teaching and research practices in elt rarely focus on nurturing and embracing the bodymindsoul connection. These practices tend to promote the idea of becoming the successful scholar in terms of being cognitively productive without necessarily interrogating what it entails building a multiplicity of identities while performing specific roles. Ascribing one’s professional identity construction to the fact of responding to neoliberal practices of individualism and competition and westernized notions of who an elt teacher is meant to be are manifestations of self-colonialism.

Understanding and interrogating how the colonial logics permeate elt educational practices, policy-making and identity building and acting upon such understandings to generate decolonial venues may lead EFL/ESL field closer to social-justice-decolonial agendas. The next section addresses some ideas for decolonial agendas from the Global South.

Understanding: Social justice and Critical-Decolonial Pedagogies

Colonization, as a global project, has mobilized minoritized-racialized communities to imagine ways to heal and resist systematic oppression. Indigenous scholars have been critical of dehumanizing-colonized-misrepresenting research agendas and have offered alternatives to decolonize research by embracing principles like interconnectedness and relationality (Wilson, 2008; Kovach, 2009). Colonialism is inextricably linked to the physical or psychological wounds resulting from racism that do not only impact the social, political, and economic realms but also the epistemological and subjective ones (Mignolo, 2005). Thus, epistemologies of the south (De Sousa Santos, 2011) emerge as an alternative for systematically marginalized social groups to reclaim and value non-western ways of knowing.

In this sense, Colombian sociologist Orlando Fals Borda borrowed the concept sentipensar [sensing-thinking] from Momposino peasants on the Atlantic Coast of Colombia. A fisherman taught Fals Borda that it was important “pensar con el corazón y sentir con la cabeza [thinking with the heart and feeling with the head]” (Moncayo, 2009). Sentipensar is a core concept in Participatory Action Research (par) that entails deeply listening to the communities and being open to learning from their sabiduría ancestral [ancestral knowledge]. In expanding Borda’s core concept, Rendón (2011) emphasizes that there is an urgent need to envision a type of education that challenges the status quo “to liberate ourselves from the hegemonic belief system that works against wholeness, social justice, and the development of moral and ethical personal and social responsibility” (p. 8).

Decoloniality is a process and practice of re-humanization, unlearning, and re-configuring the self that may be embraced in academia. Freire’s pedagogical theorizations on oppression and hope have inspired the design of decolonial pedagogies that may position as “prácticas insurgentes de resistir, re-existir y re-vivir [resistance, re-existence, and re-living insurgent practices]” (Walsh, 2013, p. 13). Likewise, Gloria Anzaldúa’s (2002) theorizations on identity construction have also inspired the emergence of pedagogies that center bodily, emotional, and spiritual experiences as political and epistemological scenarios of resistance and survival that nurture constructions of the self and communities (Bernal, et al., 2006).

Decolonial pedagogies in language education address issues such as misunderstanding the value of code-switching which has led non-native English speakers to avoid the interference of other language varieties to communicate in perfect English. Accordingly, most teachers’ expectations in relation to students’ classroom language use are informed by white supremacist ideologies that neglect the use of non-standard varieties of English and other languages. This manifestation of racism and colonialism reflect s how language teaching ideologies may be informed by racist colonial stances that lead to the oppression of minoritized students.

Colonial ideologies permeate methods, activities, relationships, identities construction, and resources used. Therefore, decolonizing the curriculum requires identifying how Western paradigms are present in materials and contents, designing materials that approach cultural diversity and value -rather than marginalize- black, indigenous, and non-Western communities, and encouraging students to play an active role in the classroom. Thus, the hierarchical order established by traditional (colonial) education may be transformed into a collaborative space where educators and students work together to plan their lesson dynamics and construct their own knowledge (Romero Walker, 2021).

To contest these colonial ideologies, Shapiro and Watson (2020) propose some “pedagogical strategies for critical language inquiry” (p. 2) to enhance racial and linguistic justice at different educational levels. These strategies are focused on two main domains: a critical language investigation and critical language conversation. The former refers to designing e.g., course materials and assignments for students to interrogate colonizing ideologies present in their context; the latter invites to pose questions to discuss “racist monolingualist ideologies that inform our pedagogies” (Shapiro & Watson, 2020, p. 13). By the same token, critical media literacy (cml) is a field and a tool that may contribute to decolonizing classrooms since it allows teachers to evaluate and analyze how industry and education use audiovisual language to perpetuate white supremacist ideologies. Once teachers and students are aware of the impact of media and its messages, they can redesign the educational resources based on multi diversity perspectives, traditions, and knowledge (Romero Walker, 2021).

Decolonial pedagogies are meant to envision ways to resist the disembodied, homogenizing and westernized logics of colonialism. In the following section we share the experience of configuring a decolonial pedagogy.

Being: Pedagogy of Possibilities (POP) -A Thread to Decolonizing EFL Teacher Education Programs

In the Understanding sections, we highlighted some of the challenges and tensions emerging in English language teaching in Colombia that are tied to self, linguistic, pedagogical, and curricular colonialism. Thus, engaging in critical-decolonial agendas, for us, involves making sense of one’s self mediated by our social locations and lived visceral experiences; these tools permit us to read/re-signify the world and to, hopefully, slightly twist any of the gears of oppressive systems. Understanding our own and others’ uniqueness and particularities allows us to develop a deeper sense of our universal humanity (Moya, 2002). It is, initially, important to acknowledge that our lived experiences and social location, i.e., the position we hold within society, are differentially marked by categories such as gender, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, and religion, among others.

These social categories may place individuals in positions of privilege and power; from a privileged position, others’ experiences may be considered delusional. Therefore, the work of indigenous peoples, critical scholars, and feminists has focused on validating lived experiences as sources of knowledge and understanding about identity construction and oppression/liberation. Experiences may be associated with the fact of “personally observing, encountering, or undergoing a particular situation [that] contains an epistemic component through which we can gain access to knowledge of the world” (Moya, 2002, pp. 38-39).

As critical-decolonizing/decolonized scholars, we approach academy as “a place of inquiry and discovery […] a place of authenticity, a place of imperfection, a place of acceptance and validation, a place of love” (Rendón, 2000, p. 141). Aware of the disembodied, disengaged, and dispassionate teaching/research/being practices present in academia and beyond, it has been our particular interest to challenge ourselves and put into practice Freire’s notion of criticality grounded on praxis. In the same vein, we seek to accept Chicanx/Latinx feminists and indigenous scholars’ invite to explore decolonial imaginaries (Pérez, 1999) and embrace our bodymindspirit[s] (Facio & Lara, 2014) as part of our commitment to our identities’ construction, consciousness-raising, spiritual development, and social justice endeavors. These efforts are represented in a pedagogical model that offers possibilities for connecting to ourselves and others.

Pedagogy of possibilities (POP) has been organically emerging since 2008 as a profound re-signification and reflect ion of teaching-learning practices and actions. Our lived experiences in being trained as EFL teachers and engaging in teaching, research, and community activities have been the terrain of thought and action. In interrogating the relationships among teachers’ positionality in the EFL classroom, power relations, and knowledge production, this pedagogy is a political practice that deliberatively “attempt[s] to influence how and what knowledge and identities are produced” (Giroux, 2006, p. 69), particularly, in EFL in/pre-service teacher-education programs and, as global citizens, in general. In our case, in 2008, the notion of configuring identities emerged beyond the idea of becoming the native-like speaker of a foreign language or the transmitters of different linguistic components (Torres-Rocha, 2019).

By the same token, Freire’s foundational work Pedagogy of the Oppressed reaffirmed an inner drive we held in terms of contributing to social change. Freire’s notion of criticality as a result of reflect ion and action (praxis) inspired the name of our research group “Knowledge in Action” - KIA (founded in 2008). Since then, the group has generated spaces of reflect ion conducive to self-transformation and consciousness-raising about systematic oppression through a series of lectures on culture and activism. For example, we have partnered with and learned from NGO Juventas, which develops language and sports programs for displaced youth and children. KIA members have also joined initiatives led by the Colombian Truth Commission and its allies like the Programa Nacional de Educación para la Paz (Educapaz) [National Program for Peace Education] and Fundación para la Reconciliación [Foundation for the Reconciliation]. Plus, Nancy, our mentor, is the tutor of the collective PaZalo Joven-Generación V+UPTC; Mónica is a member of the collective. The collective has implemented pedagogical actions through muralism, encounters like Diálogo, Arte, y Paz [Dialogue, Art, & Peace], workshops (for high school and university students), circles of truth, and intergenerational-interinstitutional-interregional dialogues. KIA’s experiences have inspired the creation of high-school research groups like Change coordinated by Mónica and the enactment of social justice in EFL studies in universities like Santo Tomás led by Ángela. These are some of the actions that contribute to our own self-growth/transformation and betterment of academic and non-academic communities. These actions reflect our positionality as critical-decolonized/ing- agents of change.

As agents of change we are “in the world and with the world” (Freire, 1996, p. 25), contributing to generating educational and interactional agendas of humanization and liberation; these agendas start with reconciling self-depreciative views so that the oppressed may position as whole authentic beings and be equipped with tools to transform oppressive limiting situations (Freire, 1996). Humanization and liberation demand from the oppressors not only to recognize themselves as victimizers but also to be solidary as a radical posture that enables them to see the oppressed as “persons who have been unjustly dealt with, deprived of their voice, cheated on the sale of their labor” (Freire, 1996, p. 32). Thus, humanization and liberation are complex endeavors that require a shift in our sense of self and positioning, entering into dialogue and solidary work with the oppressor, and being immersed in constant reflect ion and action (praxis) upon the world in order to transform it; among other complex processes.

The premises of POP are informed by social justice educational practices/processes (SJEPPS) and indigenous and Chicanx/Latinx views. Conversation circles have been part of the methodology to develop POP and the method we used to offer our testimonios in this paper. These premises position educators as bridges-mediators in constant learning-unlearning, who embrace their bodymindspirits, listen empathetically, and work FOR/WITH communities to understand and act (Carvajal Medina, 2020). The generation of this pedagogy has involved drawing from our more than a decade of experience, reflecting, designing, and implementing decolonizing syllabi and analyzing the process. Decolonizing undergraduate and graduate syllabi shifts their scope, contents, methodology, and activities that permit the participants to be in communion with one another, i.e., get to know each other, be vulnerable, embrace our humanities, and become.

So, how did this decolonial path start? What has configuring POP entailed? In 2018, Nancy enriched the scope of the undergrad courses English Workshops i and ii and the master’s classes Pedagogy and Culture and Sociolinguistics. The focus of undergrad courses (offered to students from eight and ninth semesters) was on improving linguistic skills and developing criticality. They were expected to develop communicative, cognitive, socio-affective, and pedagogical skills through class discussions and the development of a mini-scale project. Course contents emphasized the linguistic component and included topics like bilingualism, varieties of English, critical literacy, and post-methods. The graduate courses offered opportunities for students in third and fourth semesters to discuss how sociolinguistics and pedagogy could potentially improve the teaching of English locally.

When Nancy returned to Colombia, after finishing her Ph.D. in the U.S., she questioned the role of EFL educators in a country where Cátedra para la paz was proposed by the Ministry of Education for a nation that was discursively experiencing post-conflict but that, in reality, was witnessing the increasing number of social leaders’ systematic assassination. To this day, the murders continue. This concern and the verification, through her research group, that EFL/TESOL educators can be agents of change led her to enrich English workshops I and II courses by addressing both linguistic and social justice education components. The social justice component invited pre-service teachers to develop criticality and ACT. Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Boyd’s Social Justice Literacies in the English Classroom, and articles from Rethinking Schools magazines offered a nuanced view of EFL educators’ role (Carvajal Medina, 2020). Every course included a series of workshops to engage in self and collective reflect ion and dialogue about oppressive systems, philosophies of teaching/being, personal/professional identities construction, biases and stereotypes, and alternatives for social justice education (Carvajal Medina, 2020).

Pre-service teachers had three options with different alternatives to take part in social justice practices (see Annex 1). If any of the options did not resonate with students, they could discuss other alternatives with the teacher. A class journal on this exercise was kept as a space of dialogue between the teacher and pre-service teachers. Academic writing in the course was strengthened with peer, teacher, and English assistant’s feedback. Guidelines were offered to direct the process.

The graduate courses Sociolinguistics and Pedagogy and Culture have been enriched by incorporating socio-cultural theories and indigenous-peasant-Chicanx/Latinx-African descendants’ feminist epistemologies. Both pre- and in-service teachers have written essays on their philosophies of teaching, participated in workshops offered by the leading teacher, engaged in dialogue with guest speakers whose work they read as part of course requirements, and kept a reading class diary-journal (see Annex 2). In this journal, students are given three prompts where they are invited to explore emotions, visually represent an idea or cluster of ideas that talked to their mindbodyspirits (e.g., through drawings, collages, paintings, other texts, songs, and poems), and put into conversation the authors they read. As part of the course dynamics, students self-evaluate and reflect on their process throughout the course and evaluate the course in relation to materials, activities, and methodology.

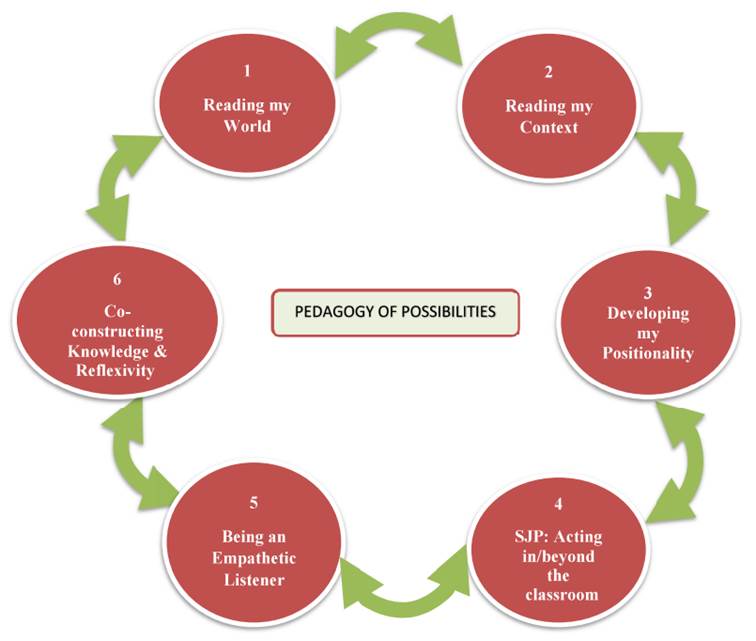

These classroom experiences inspired the emergence of the non-linear stages of pedagogy of possibilities (Figure 1).

Every stage mobilizes students into deep self- reflect ive practices to wonder about: their sense of self and identities building; the mechanisms of systems of oppression; the tools that may be used for their own and communities’ transformation to create creative, empathetic, and caring nets. We invite those interested in critical decolonial endeavors to implement and enrich the discussion about the challenges and possibilities of this pedagogy. We invite you to be part of our community of bodymindspirited scholars!

Dialoguing: A Thread to Critical Community Auto-Ethnography

Higher education institutions continue to ascribe to the audit culture inherited from neoliberalism. As argued by Rinehart and Earl (2016), “the audit culture -with its statistics, accountability measures and so forth (of “what counts”)- works to reify and (re)produce such competitive educational and research models, while simultaneously insisting on cooperation, collegiality, and collaboration” (p. 3). This illustrates the gap that needs to be diminished between discourse and practice. The audit or surveillance culture configures research gatekeepers who determine “what is seen as acceptable research, what is encouraged, what kinds of questions we are rewarded for asking, who gets to do the asking” (Rinehart & Earl, 2016, p. 4). Within this neoliberal academic landscape, critical-decolonial-ethnographic practices face challenges when it comes to publishing and being welcomed, acknowledged, and valued in the research field. However, these methodologies position as venues of resistance that continue to expand.

For instance, auto-duo-collaborative ethnographies are evolving practices that promote an ethics of care and continue to be re-signified by researchers’ experiences. All of them are characterized by embracing reflexivity and narratives. Duo-ethnography creates dialogic storytelling and currere through which “one can reclaim agency, authority, and authorship over one’s life” (Norris & Sawyer, 2012 as cited in Rinehart & Earl, 2016, p. 6). In turn, auto-ethnography “demands a reflexivity that is mindful, contemplative, and generous - both to ourselves, our way of being in the world, and to others, and their ways of existing in the world” (Rinehart & Earl, 2016, p. 5). In other words, auto-ethnography does not necessarily focus on turning the gaze to ourselves as objects and subjects but rather to storytell in “a way for us to be present to each other” (Jones et al., 2013 as cited in Rinehart & Earl, 2016, p. 5). Lastly, a distinguishing component in collaborative ethnographies is the generation of “reciprocal trust and respect for contentious positions and values [to come] to place of compromise, understanding, or some resolution” (Rinehart & Earl, 2016, p. 8). Overall, it may be argued that one of the distinguishing traits in auto-duo-collaborative ethnographies is the number of authors/story-tellers who engage in reflect ive, caring, and respectful interactions and writing practices.

As KIA family, we have engaged in critical community autoethnography that allows us to embrace the values mentioned above and incorporate ethnography, testimonios, and critical pedagogy. The synergy between autoethnography and critical pedagogy allowed us to resist the norms instituted by the dominant practices in academia and “problematiz[e] our own actions and practices from a sociocultural perspective” (Tilley-Lubbs, 2016, p. 3). Thus, we dialogically collaborate through writing (Pensoneau-Conway, et al., 2014; Rinehart & Earl, 2016) aiming to “ reflect upon and analyze [our] individual and collective experiences” (Zilonka, et al., 2019) when being involved in decolonial and social justice education and research agendas.

Autoethnographies are resistance narratives where the seven of us have weaved lived experiences and a collective voice to transgress the writing standard of sole authorship. The dialogue has evolved while honoring our stories and multiplicity of identities. Autoethnographies are represented in various ways (Rinehart & Earl, 2016). In this plural-communal autoethnography, we offer ethnographic narratives (testimonios and artwork) that “convey the vitality of [our] experiences within a framing that allows the reader to make connections” (Mills & Morton, 2013, p. 2) and draw their own conclusions. Testimonios are sites of knowledge, basis for theorization, and offer understandings of a particular reality (Delgado Bernal, et al., 2012). These are “document silenced histories” (The Latina Feminist Group, 2001, p. 3) and have “the power to give our life experiences an authority not historically granted by systems of knowledge and power” (Flores Carmona, 2014).

For Anzaldúa (2015) “conocimiento questions conventional knowledge’s current categories, classification, and contents” (p. 119). Thus, art-making is conocimiento (Anzaldúa, 2015). Creative arts are the bridge to connect to one’s, others’, and the earth’s struggles to generate conocimiento which in turn is a form of spiritual inquiry (Anzaldúa, 2015). In this way, Arts-based practices are useful, on one hand, to mobilize social justice agendas, and, on the other hand, to engage in identity work (Leavy, 2009). Furthermore, arts-based practices are used to promote dialogue and facilitate empathy (Leavy, 2009).

The knowledge-gathering methods (Kovach, 2009) we bring in this paper are excerpts of re-signified testimonios and visual representations of our experiences in teaching, researching, and partaking in undergraduate and graduate courses, where we implemented pedagogy of possibilities between 2018-2020. As part of the courses’ requirements, some journals were kept. However, we decided to engage in a more in-depth conversation in 2018. Through Google Docs, we started to write testimonios in 2018 and 2020. Nancy invited in/pre-service teachers to write about individual transformations and lessons learned from social-justice-oriented courses and research practices. Writing stopped for a while because everyone was experiencing important changes which made it difficult to continue nourishing the dialogue. In 2021, we re-visited those dialogues and continued writing and re-signifying the experience. We talked about the initial work done and made decisions about the structure of our dialogue. For about four months, we had the opportunity to access the document at any time. Nevertheless, we did not plan encounters to write this because we wanted writing to organically evolve. In this collaborative writing, in which we continuously swapped roles, i.e., being the audience of our colleagues’ writings and, at the same time, writers of our own testimonies, we showed vulnerability.

Nancy, the tutor of the courses, believes in the transformational power of arts and encourages non-verbal ways of expression during the implementation of POP. Thus, the second knowledge-gathering method of this study are visual representations we and some of our research participants made between 2018 and 2022. These creative works are one of the languages we use to storytell They were made as part of courses we led/took and the result of dreams we had.

Testimonios and visual art have allowed us to explore a core question: How may critical decolonial pedagogies like pedagogy of possibilities enhance elf pre/in-service teachers’ personal and professional identity constructions and positionalities (philosophies of being/teaching/researching)? We used theoretical coding, i.e., “key phrase[s] that trigger discussion of theory itself” (Saldaña, 2016, p. 250), to underpin the transformation from research to Re-Self-we-search. This key phrase led us to discuss identity construction grounded on Chicanx/Latinx notions like path of conocimiento and spiritual activism.

Considering creative-arts and metaphors as languages to represent our viewpoints, the following section illustrates how the idea of the threads and weaving has been present not solely in our data analysis but also in the writing of the paper and the relationships we have built.

Entretejidxs: On Being and Becoming

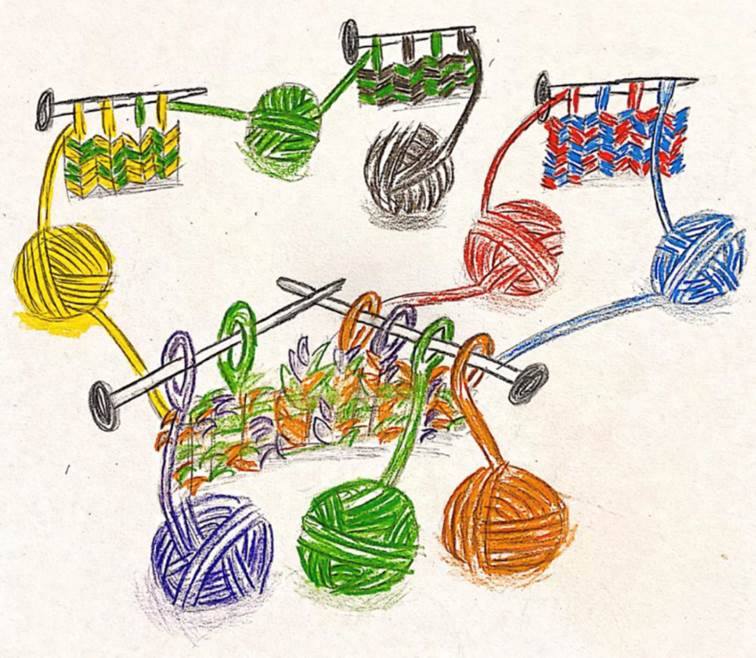

What has the experience of encountering in different stages of our professional and personal lives meant for us? How do we see each other? Our walk has been paved with respect, love, and connection. We have found a space to be in relation, become, and belong. We think of ourselves as those diverse unique colorful skeins of wool (Figure 2) whose threads enrich a tapestry of understandings of who we are and who we may become, what our function and role in the world are, and what our concerns, passions, and motivations are. As becoming threads (permeated by de-constructing, learning/un-learning processes), we continue expanding the weaving of the tapestry in the spaces we occupy, the professional roles we hold, and the communities we create/generate and/or are part of. Wherever we may go as KIAnxs, we will be entretejidxs while always respecting the individual decisions and paths walked by its members, which is the normal course of becoming. We do not aim for complete coherence but at least for a little integrity in what we do. In Becoming, Embracing, and Transforming we discuss three threads (data analysis) seeking to answer the core question addressed in this article.

Becoming: A Thread/Bridge Home -A Bridge to the SelfFigure 6

As academics of the heart (Rendón, 2000), we start critically examining what gives sense to our own selves while honoring our roots and the communities we have been part of. We keep weaving layers of intergenerational understanding and transformation. Having been part of undergrad or grad courses (1-year process) and developed research studies afterward (1-2 years), students were asked to share how they positioned in the EFL field. The excerpts presented here correspond to their evolving answers written since 2018 and re-visited and re-signified in 2021. Their narratives are accompanied by visual representations that resulted whether from the workshop Philosophy of Teaching and Professional Identity or the exercises they developed while conducting their research studies with high school students (between 2018-2020).

The workshop on teaching philosophy and identity invites undergrad and graduate students to answer three questions through a visual representation (an image, a symbol, or other representations). The first question is Where do I come from? It invites them to not only focus on geographical location but also address the traditions, customs, beliefs, knowledges, theories, experiences, and other aspects/areas that may inform who they are at the moment of doing the exercise. The second question (i.e., Why am I here?) calls on pre/in-service teachers to initially wonder about the reasons why they are at the program, the course, the university, and secondly, about what they consider their function in life, i.e., what they think is the purpose of their lives and their career. The final question (i.e., How do I see myself here and now?) asks students to slightly and introspectively look into the ways they think of themselves (Figure 3).

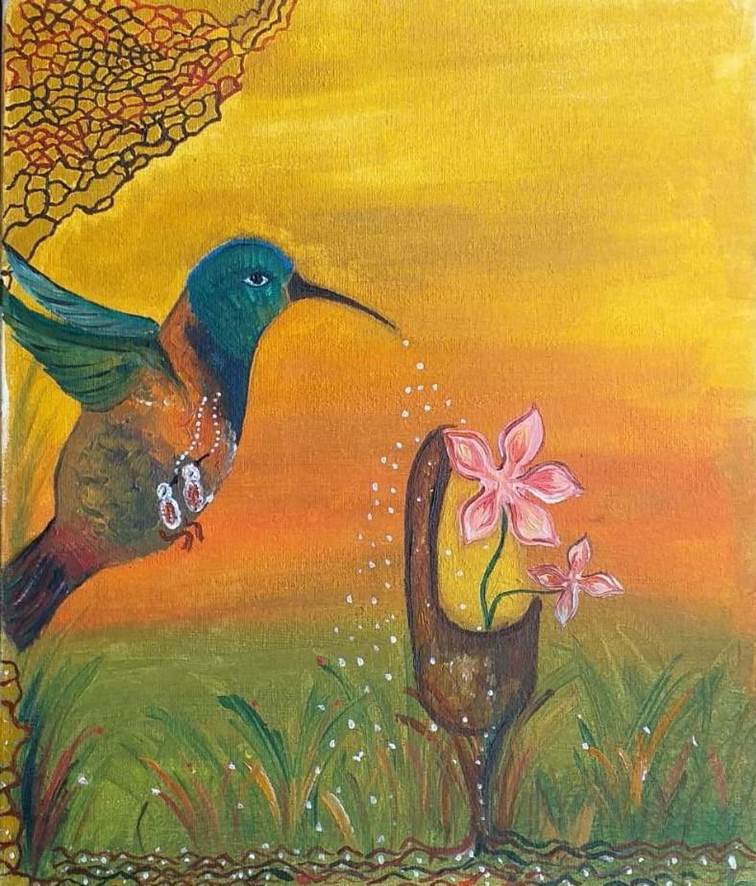

Note: Painting by V. R, July 23rd, 2019 (Taken from Ramírez Sánchez, 2019).

Figure 3 Social Justice and Racial Discrimination Understandings in the EFL classroom

The following storytelling emerged when reflect ing about how we identify and position ourselves:

Mariana: I identify myself as a being who is discovering day by day a way to be more human by means of having a sense of belonging to society and engaged with contributing to social justice based on equity relations.

V.R. was one of Mariana’s students who participated in a research study on social justice and racial discrimination. V.R. made this painting to answer the question Who am I? As a Venezuelan, V.R. illustrates how she has experienced misogyny and xenophobia in Colombia’s educational settings.

Mónica: I am a woman who feels proud of her roots. Raised under the legacy of a generation of persistent women, granddaughter of Carmen Alicia, part of a lovely family. Daughter of Mother Earth, amazed by the greatness of nature. I am a person who works daily to become a better human, I am a passionate teacher and a believer that education is the base of social justice and decolonization (Figure 4).

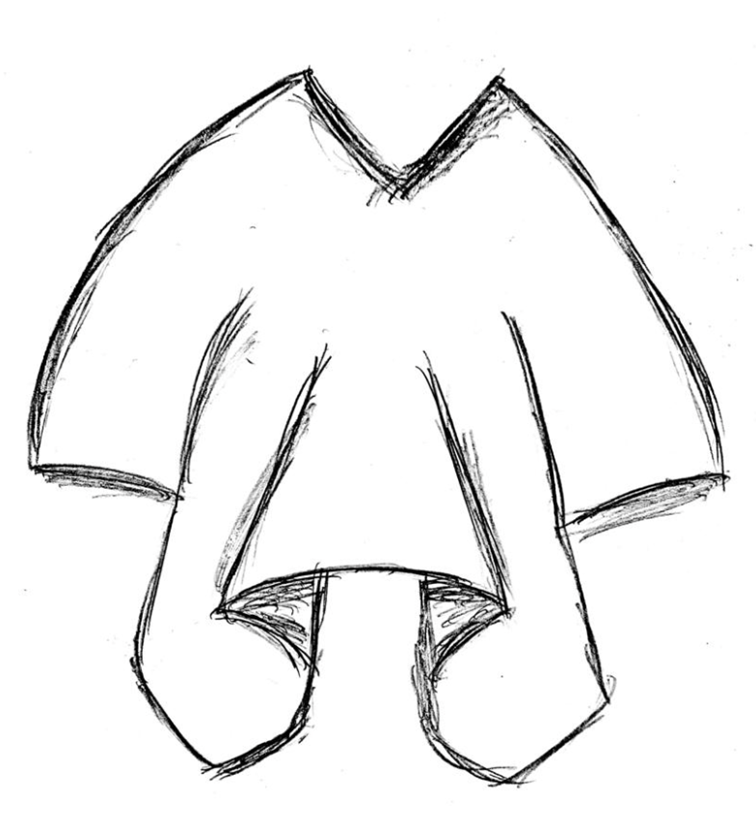

Ángela: I am the daughter of the first generation of a peasant family that had the opportunity to go to the university. I am a tangle of threads that are continuously intertwining and untwining and keep reshaping who I am. A daughter, sister, and wife who loves her family. I am a peasant legacy who loves her roots. I am a teacher-researcher whose voice wants to vindicate peasants’ roots. As a peasants’ daughter, la ruana has a special meaning for me. All my life, I saw my dad wearing a ruana. He used to have two, one as his only armor to withstand long working hours when he worked the land. The other one, to wear when he was at home, or when he wanted to attend special events, in his case, everything related to catholic celebrations. When I was a child, dad liked to cover me up in his ruana while telling me stories about my grandparents, and their lives in la vereda Reginaldo, in Mongui, his hometown. Dad passed away, but his legacy remains intact. For me, la ruana represents a community whose struggles are also mine (Figure 5).

Note. Painting by Ángela. First session, Seminar Pedagogy, and Culture, August 3rd, 2018. Exercise: Through a visual representation answer the following questions: Where do I come from? Why am I here? How do I see myself here and now?

Figure 5 La Ruana

Nancy: I am the granddaughter of peasants from Socha and San Mateo, the daughter of Margarita and Marco, the aunty, the sister, la madrina de mis sobrin@s, the lover... I am a human being under construction; it is a messy process where I have fallen and stood up hopefully with the lesson learned (laughter). Well... sometimes it takes more than a fall to learn a lesson.

Dayana: I am the daughter of Liden and Magaly who come from a small and traditional town. I am a woman who had the chance to go outside that town and explore the world. I identify as a human being who keeps learning day by day, who keeps doing her best to become a better person for myself and the world.

Cristian: I am the son of Esperanza and Arnulfo. I am a friend, a colleague, a person interested in getting to know others, and who likes interaction. I come from Moniquirá. The word Moniquirá itself means a lot to me. I am proud of my town and its people. I identify myself as a person who wants to leave a legacy for others, even if it is a small one. I would be very happy if I can contribute with a little part of myself

Note: Painting by Cristian. Workshop: “Philosophy of Teaching”, Sociolinguistics Seminar, March 6, 2020.

Figure 6 Moniquirá

Harol: Raised by a caring woman head of household, I am the only son out of five daughters. In my family, cooking is a way of expressing love. I am a human who always tries to be aware of others and who exposes himself to prejudice every day. My identity is constantly (re)built by my own experiences and the knowledge I am offered by wonderful people I have met. I am super proud to be gay. Exploring the world has taught me I belong to the world, but the world does not belong to me.

During their teacher-education training program, these pre/in-service teachers were never offered a space to deeply reflect about their ancestral roots and heritage, their sense of self and process of identity construction, or the real motivations for becoming teachers. Responding to these key questions, although in not absolute ways, offer insights on EFL pre/in-service teachers’ positionality. Anzaldúa (2015) argues that “[i]dentity is relational. Who and what we are depends on those surrounding us, a mix of our interactions with our alrededores/environments, with new and old narratives” (p. 69). Carmen, Mónica’s abue, is her source of inspiration and one of the roots on which she stands. Her visual representation illustrates her connection to mother earth (Figure 4); her awareness of the importance of caring about the environment positions her as a “passionate teacher and a believer that education is the base of social justice and decolonization” (Mónica, testimonio, sic). In fact, Mónica’s MA’s thesis focused on developing critical environmental literacies in high schoolers.

Similarly, for Ángela, la ruana (Figure 5) is a symbol and a reminder of her dad’s peasant roots. She positions herself as “a teacher-researcher whose voice wants to vindicate peasants’ roots” (Ángela, testimonio, sic). In this vein, Ángela asserts that “la ruana represents community whose struggles are also mine” (Ángela, testimonio, sic). She embraced her peasant roots when she explored intergenerational dialogues in her hometown and applied participatory-placed and project-based methodologies through which eighth-graders could also position as researchers themselves. La ruana was the metaphor Ángela used to conduct data analysis to explain the relationship between the process of making wool and the process of identity construction, EFL teaching, and students’ English writing processes.

Thus, acknowledging we hold present, past, future relations with others and mother earth is an important value to position as agents of change. As human beings under construction, as our mentor is used to identify herself, we understand that “identities are subject to multiple determinations and to a continual process of verification that takes place over the course of an individual’s life through her[his] interaction with the society she lives in” (Moya, 2002, p. 41). Cristian, Dayana, and Harol think of their identities as a constant re-building and acknowledge that lived experiences inform their identities construction. Harol is open about his sexual orientation and shows that when he states, “exploring the world has taught me that I belong to the world, but the world does not belong to me” (Harol, testimony, sic). Mariana reads the socio-political context and brings one of her students’ art pieces (Figure 3) to illustrate how challenging it is to belong when xenophobia is latent. Mariana herself has also struggled with developing a sense of belonging. So, through her student’s experience, Mariana makes sense of her own experiences.

Teaching is a form of activism since it has the “potential to shape individual’s thinking and actions” (Boyd, 2017, p. 7). Thus, the implementation of the stages of pedagogy of possibilities represents a door for students/mentor to acknowledge their peasant backgrounds and traditions, their relationship with mother earth, and honor relationships built with their peers, teacher, and students. In exploring their lived experiences, these pre/in-service teachers start to position as selves in relation and agents of change “who [want] to leave a legacy for others, even if it is a small one” (Cristian, testimonio, sic). Therefore, in POP, the professor offers spaces where everyone’s presence is acknowledged, respected, and valued. She offers a space where participants may reconcile with parts of their identities and be proud of who they are. Self-value is an important step into positioning as agents of change.

Embracing: In lack’ech/ I see you -A Thread to a Pedagogy of Connection, Well-being, and Spirituality

“Writing is a process of discovery and perception that produces knowledge and conocimiento (insight)” (Anzaldúa, 2015, p. 1). In this section we dialogue and generate insights about the path we have walked together. The question that guided the dialogue was: what word would you use to describe our work since 2008?

Mariana: When I take a look at the past, a word that can describe our work is encouragement. Encouragement has created a new human being who is constantly deconstructing and rebuilding herself. The process of being a social justice educator focused on antiracist pedagogies inside the EFL classroom has represented a personal and professional growth in my life. Although it has been a process with ups and downs, I have understood how important my commitment to society is and how crucial it is to have a sense of belonging to our people, our communities, and our earth to achieve equal relations and feel loved, honored, and respected as we are.

Cristian: Mariana, I find it interesting how you state the importance of “having a sense of belonging” not just as human beings, but also in professional settings. For us, as educators, it is great when we see the fruit of what we cultivated. When we praise the process, it makes us aware of the hardships and the moments of ease we went through. Every experience that we have lived, has shaped to some extent who we are, and who we are is what matters, we are all equally different, and we have got a lot to learn from one another.

Mónica: When I think about our work since 2018, the first word that comes to my mind is growth. As a teacher-researcher aiming at enhancing social justice practices in Colombian classrooms, I have re-signified my perception of education. Being an educator who works for social transformation is a challenge. We have to face demotivated teachers and students who do not comprehend the essence of education. Sometimes, you feel judged and scared. Joining forces is hard, people’s faith in humanity is so destroyed that just a few dare to believe in good intentions. However, as Mariana mentioned, being conscious about the positive transformations we can promote in our communities encourages us to (re)dignify our feelings, beliefs, ideologies, and purposes. We feel encouraged to take action, to get people engaged, to change our reality.

Ángela: The work that we started in 2018, can be described as a healing process. The idea that I had about research, as a space where the “only important aspect of our identity was whether or not our minds functioned” (hooks, 2014, p. 16) was transformed by the KIA research group. As a novice researcher, this academic space embraced my story and my roots, making me feel that the “intellectual questing for a union of mind, body, and spirit” (Hooks, 2014, p. 16) had been successfully accomplished. As a result of finding a place where I felt I belonged, with all who I am, I started an unlearning and learning transformation that was later, also, experienced by the group of students that were part of my research project. I understood that what I was going through, feeling how my identities were being fragmented by the academy, was “as much a personal struggle as it [was] a group struggle” (Weenie, 2000, p. 65) Thus, understanding the importance of decolonizing those teaching and research practices that dehumanize the knowledge has been absolutely rewarding. Similarly, having started working with social justice pedagogies, turning research experiences into a more meaningful exercise for the communities and myself has helped to build in a more honest way my teaching philosophy and my positionality as a researcher.

Dayana: As Mónica said, being a teacher enhancing social justice practices is extremely challenging due to the lack of motivation we find in our classrooms. I remember the way many students just did not pay attention to the workshops or just did not care at all about social justice. They were used to never being listened to, to being ignored and judged. I could say it is a very difficult path because you have to teach people how to believe again, how to have faith in humanity, and how to be brave enough to speak up and let everybody know that our lives and thoughts matter.

Mónica: Getting immersed in decolonial dialogues and practices has allowed me to recognize my inner self. In that sense, I agree with Ángela and Dayana when they say that our pathway through critical-decolonial pedagogies has been a way to heal and reconstruct ourselves. Once you take the risk to really try to know, understand and accept yourself, you start loving who you are. I deeply believe that making peace with yourself is necessary to try to help others. My whole experience as a teacher-researcher has configured me into the way I am today. As a proud KIANA, I can affirm that every time I have worked with and for the community, I have become a better human and professional. Every day I keep healing, constructing, and growing. All this process gives me hope and encourages me to continue spreading the seed of social justice and critical decolonial practices beyond the classroom.

Cristian: I agree with your interventions. In my case, I have experienced some changes over the last two years. I have reflect ed upon the way I get into the classroom, how my students relate to each other, and how my lessons can help them interact in respectful ways. I have discovered that every student has a voice and their voices are really worth being heard. Now, I can see how my classroom is formed by a community; inside this community every person matters, every human being matters, every idea is important, and every experience that has shaped us is important, too. Getting immersed in such social justice practices has led me to change my cosmovision of the process of teaching and has made me more aware of my students’ human entity.

Mónica: I find relevant the connection you establish between personal and professional growth and a sense of belonging. For me, getting involved in critical decolonial dialogues and practices has also been an opportunity to grow as an individual, but I also think we are co-dependent beings and from our individuality, we can work to grow together. Once you get involved in social justice practices you feel the need to work and fight for equality, you perceive the other as yourself. You cannot grow if your community does not. I think we all feel the same way.

Dayana: Mariana, I agree with you in the way you express how important our commitment to society is. When I was learning about pedagogy, I used to think I was just going to teach my students how to speak a foreign language. Then, I realized they were little human beings who needed guidance not only with their English but also with their lives, their hopes, and their beliefs.

Ángela: However, working with social justice pedagogies has not been an easy path. Therefore, I identify with Mónica and Mariana’s words. Personally, I witnessed how challenging it can be to propose students and community members of a rural area to participate actively in the educational projects in their territories when the classrooms have been perpetuating a culture of silenced learning. That situation made me reflect on my role as a social justice-oriented teacher. As Mariana mentions, the commitment to our communities and their realities is paramount. Actions like listening to them, empathizing with their struggles, and empowering their voices is absolutely important. Only in this way, and as stated by Mónica, making education transcends the classroom walls is how meaningful transformations can be evidenced.

Mónica: Ángelita, I completely share with you the perception of KIA as the inspiration for our growth, not only as professionals but also as humans. Being able to comprehend the relevance of connecting heart and mind was a key element to our configuration as teacher-researchers. In a world where injustice and hate exist, the pedagogy of love is necessary. As a family, KIA embraced us all. Through this experience, we have learned to accept each other as individuals, to care about our peers, to work, and fight for equality and justice.

Dayana: The first word that comes to my mind when I think about our work in 2018 is (re)construction. All of the experiences I had since then have led me to a path of change and reconstruction not only as a teacher but as a human being. I consider I have been going through different stages of change such as understanding and reflecting on the oppression in our classrooms, personal lives, and society in general. During this stage, I assumed my role as a teacher who works with diverse generations. Besides, I got to see the way I can lead other people to their liberation and change. The change and reconstruction of my life has been a challenging process as I had to recognize my oppression towards others. Once I could recognize it and transform it, I became aware of how my words and actions can hurt others. In this way, I learned the importance of thinking beyond the self. One of the aspects that influenced my transformation in an enormous way was being able to hear the actions I made as an oppressor. This made me realize that I had to rethink myself and reinvent my way of acting and speaking.

Mónica: I agree with the idea that recognizing and reconstructing ourselves implies a deep analysis of the way we feel, think, and act. I consider that humans have been involved in oppressive practices from the moment that our ancestors were colonized. For a long time, we have lived in a culture where people dream of having power and controlling everything, even nature. We are so used to these dynamics that we have normalized oppression; it is part of most of our daily lives and we do not even perceive it. Accordingly, the first step to transformation is identifying ourselves as oppressors and start working to recognize and value others, so that we get to understand them and, by the way, become more human.

Harol: I feel your words when describing your individual transformations. I live in a constant reconstruction allowing myself to understand myself and others. Since 2018, I opened up to listening. I am still dealing with my own prejudices, always trying to be aware that people that are sharing their fears, their struggles, their achievements, or their experiences are unique human beings. Due to that process, I have understood my humanity better.

Nancy: I feel you and see you all. Every time I find a challenging, confusing reality I wonder What can we do? Where can we go next? Even since we founded KIA in 2008 the word possibility has been the door to figure out the puzzle of uncertainty and doubt. Getting to know you and working together has permitted me look at my own fears while creating spaces of hope and change. I thank you all for being my inspiration when I lose hope, my strength when it seems there is not a way out. Thank you for your openness and generous kindred hearts…

Our dialogue continues…

Transforming: A Thread from Research to Re-Self- we-search

Our testimonios reflect the challenges faced when embracing critical-social justice-oriented agendas: encountering demotivated colleagues and students who have lost faith in humanity, acknowledging, and changing one’s oppressive practices, and deconstructing the sense of fragmentation and no-belonging usually promoted in academy. Nevertheless, walking into critical-decolonial pedagogical practices has also permitted us to embark on processes of self-awareness, self-reconstruction, the recognition of others’ humanity, growth, and healing. Entering the decolonial terrain of the self has moved us to explore the subjectivity of being and reflect upon the evolution of our path of conocimiento (Anzaldúa, 2015). We position as bodymindspirit[s] (Facio & Lara, 2014) willing to:

deepen the range of perception […] link inner reflect ion and vision-the mental, emotional, instinctive, imaginal, spiritual, and subtle bodily awareness-with social, political action and lived experiences to generate subversive knowledges (Anzaldúa, 2015, p. 120).

We engage in a form of spiritual inquiry, conocimiento, that “is reached via creative acts- writing, art-making, dancing, healing, teaching, meditation, and spiritual activism” (Anzaldúa, 2015, p. 119). Lara and Facio (2014) argue that “[c]oncretizing our spiritual lives through words and image, and in turn, spiritualizing our material lives, allows us to paint a fuller picture of our realities” (p. 11). We agree with these perspectives because spirituality is something we do (Lara & Facio, 2014). Our spiritual inquiry - path of conocimiento- started by revisiting the places and memories, stories, and histories, that have influenced the ways we think of/see ourselves and the motivations behind our ongoing learning-unlearning processes. The ways we self-identify speak to different layers of our identities situated in relationships to our own selves, the ancestors, the land, and communities.

Considering that any individual can be both colonized-victim and colonizer-oppressor, in our encounters, we have embraced our vulnerability to hold open and honest dialogues to identify and interrogate oppressive beliefs and biases. In examining the potential harm, a culturally-constructed belief may have in threatening individual’s dignity, we have been able to re-assess and transform them, just like Dayana did:

The change and reconstruction of my life has been a challenging process as I had to recognize my oppression towards others. Once I could recognize it and transform it, I became aware of how my words and actions can hurt others (Dayana, testimony).

As argued by maestra Gloria Anzaldúa (2015) path of conocimiento:

requires that [we] encounter [our] shadow side and confront what [we]’ve programmed [ourselves] (and have been reprogrammed by [our] cultures to avoid (desconocer), to confront the traits and habits distorting how [we] see reality and inhibiting the full use of our facultades (Anzaldúa, 2015, p. 118)

If we walk away from the know-it-all perfect scholar and acknowledge we make mistakes and can say “I’m sorry”, we leave a door open to self-awareness. Listening to Harol’s emotional testimonio in the class circle as he makes sense of his biased thoughts towards a minoritized group and witnessing how Dayana, he, and one of their closest friends become observant of two street vendors and make the conscious decision of buying in the two stalls, is a sign for themselves and the class that something in their reading of the world is starting to change. After awareness, acceptance and forgiveness of oneself start while being surrounded by the class support and care. We learn lessons individually and collectively and in the same way, we are meant to heal individual and collective wounds. But, starting this type of engagement is not always welcomed, respected, or understood. The first classes, usually, generate wonder, confusion, or uncertainty. Who is this teacher who is talking about love, care, and social justice? Where is she coming from? What are her intentions? What does the focus of this course have to do with our professional development? Building trust and confidence has allowed us to have honest conversations. An example of this is Harol’s reflect ion about his experience in taking two courses with professor Nancy in 2018 and in engaging in a research project in 2019:

At that moment [2018], I was just confused. By the time, I realized it was an action of compassion, understanding and caring for others. This type of action would continue positively confusing me every class. I personally think that people fear the unknown and refuse it. There were moments when I felt uncomfortable because that persevering teacher kept pushing with her actions and words. Now I know she was leading me through a path I was urged to find. What I got from her is that there exists hope and there is something that can be done to work for a reconstruction of humanity, equality, peace, and acceptance (Harol, testimony).

Despite initial tensions, POP has permitted to interrogate EFL educators’ personal/professional identities and positionalities. Indigenous traditions remind us that we are interconnected beings who learn while being in relation to land-our own selves- others-the stars-the animals- the cosmos (Smith, 2012; Wilson, 2008). The Lakota saying “Mitakuye Oyasin” usually translated as “everything is related” (Grant, 2017), the Ubuntu concept “I am because we are” (Sulamoyo, 2010; Dillard, 2020), and the Mayan principle “In Lak’ech” (Valdéz, 1990) portray relationality as the basis on which community-building is feasible. Acknowledging our humanity in others’ humanities allows us to re-assess the values that inform our philosophies of life. In Tutu’s (2003) words, Ubuntu means that “I am fully me only, if you are all you can be” (p. 7). “In Lak’ech” is a principle present in POP, as a constant reminder for respecting each person’s growth, understanding that an individual’s discourses, attitudes, and behaviors correspond to his/her level of understanding and consciousness development. Acknowledging “we are mirrors to each other” (Valdéz, 1990) is a needed reminder of our shared vulnerability and imperfection. “inlak’ech: Si te amo y te respeto a ti, me amo y respeto yo; si te hago daño a ti, me hago daño a mi [If I love you and respect you, I love and respect myself; if I hurt you, I hurt myself]” (Valdéz, 1990, p. 174).

Walking the Talk: Somos Semilla [We Are Seeds]

Sept 17, 2020. I had a dream. An eight-year-old girl was standing in the middle of a green field. A few flowers blossomed as a tiny bird spread a few seeds. Suddenly, a hummingbird and others residing within her/him could spread far more seeds in a larger terrain. Hope resonated in my mind as I woke up. Hope is cultivated, I remembered Vandana Shiva says. And cultivating hope is a spiritual practice, she remarks. So, we are seeds, seeds of hope and change. (Nancy’s notes, 2020)

Engaging in the critical-decolonizing pedagogy of possibilities permits configuring philosophies of being/teaching/researching while developing a sense of belonging, acknowledging our own and others’ humanities, thinking communally, and understanding oppression to engage in healing and transformation and become agents of change. As growing seeds of change (Figure 7), we engage in humanizing and decolonizing efforts by building bridges to the self, i.e., encouraging processes to strengthen self-love, self- and mutual recognition, and self and collective value so that being and becoming be less threatening. Critical-decolonial agendas entail embracing one another by moving away from teaching/research practices that fragment and isolate and mobilizing towards pedagogies that promote connection, growth, and healing. Indigenous and feminist epistemologies offer an ontological shift that informs decolonial-re/humanizing philosophies of being/teaching/researching.

In approaching writing as a process of discovery and insight, we have listened to and acknowledged each other’s voices through words and images. Our reflexive dialogue about social justice and decolonial practices in EFL education reflect our steps into embodying teaching philosophies beyond competition and individualism. In sharing our insights with national and international communities in interdisciplinary fields, we invite to “ACKNOWLEDGE”, “CONNECT”, and “ACT” (Annex 3), in order to embrace our history-stories and values. Our critical-decolonial agenda invites to find/listen to our voices and tune up on everyone else’s.

Why is it urgent to re-envision education so that we can decolonize ourselves? covid-19 and the tensions between Russia and Ukraine evidence that “[…] fear, ignorance, greed, overconsumption, and a voracious appetite for power is what this war is about” (Anzaldúa, 2015, p. 15). This reality can be trans-shaped by changing our perspectives (Anzaldúa, 2015) and embracing service and acknowledgement as the values that inform our being/doing. As seeds, we engage in Re-Self-WE-Search through reflect ive and collective dialogue-writing as a resistance and political act to avoid erasure and homogenization. As seeds, we commit to decolonizing the self by progressively embracing our bodymindspirits as sources of knowledge and understanding. This step leads towards societal transformation. As seeds, we keep weaving feeling-thinking-becoming threads. This is the kind of spirited work that speaks to our souls. What speaks to your soul?