Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal

versão impressa ISSN 0123-4641

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. n.6 Bogotá jan./dez. 2004

Andrea García Obregon***

* Doctora en Educación de la Universidad de Arizona. Profesora titular e investigadora de la Maestría en Lingüística Aplicada a la Enseñanza del Inglés en la Facultad de Ciencias y Educación de la Universidad Distrital Francisco Jose de Caldas en Bogotá, Colombia. Actualmente es la directora editorial de la revista Colombian Applied Linguistics que publica la Universidad Distrital anualmente.

E-mail:aclavijo@andinet.com

** Doctora en Educación de la Universidad de Arizona. Associate Principal and Literacy Specialist for the Hong Kong International School in Hong Kong.

E-mail: afreeman@hkis.edu.hk

*** Doctora en Educación de la Universidad de Arizona, profesora asistente in the Department of Literacy Studies, School of Education and Allied Human Services, Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York.

Email: Andrea.Garcia-Obregon@hofstra.edu

Received: 03-14-2004 / Accepted: 09-10-2004

Abstract

This article describes first and second grade2 children's writing and focuses on the use of punctuation as they develop awareness of the orthographic features of texts. This exploratory study was carried out with a group of first and second grade bilingual children in a school in Tucson, Arizona. Our research project focused on observing the process bilingual children followed when writing the story of Caperucita Roja to analyze the content of their texts in the different episodes of their stories and the use of punctuation around dialogue and narratives. The findings show that the majority of children were aware of the use of punctuation marks in their writing. We found a direct relation between punctuation and the use of dialogue (indirect speech) in children texts. Children used additional (syntactic and lexical) forms in their texts that demonstrate that they know the use of direct speech. Children's texts exhibited very little use of punctuation in their narratives; they only used period and capital letters.

Key words: Children's biliteracy process, punctuation in children's texts, writing development in bilingual contexts.

Resumen

Este artículo describe el proceso de escritura de niños de primer y segundo grado para enfocarse en el uso que hacen de los signos de puntuación como característica fundamental de los textos escritos. El presente estudio exploratorio fue desarrollado con un grupo de niños bilingües de primer / segundo grado en una escuela en Tucson, Arizona. Nuestra investigación estuvo enfocada en la observación del proceso de escritura de niños bilingües cuando se les pidió que escribieran la historia de Caperucita Roja. Analizamos el contenido de la historia en los diferentes episodios y el uso que los niños hicieron de los signos de puntuación en el diálogo y en la narración. Los hallazgos muestran que la mayoría de niños en nuestro estudio fueron conscientes del uso de los signos de puntuación en su escritura. Encontramos correlación directa entre el uso de signos de puntuación y la presencia de dialogo en los textos escritos por los niños. Los niños usaron formas adicionales (sintácticas y léxicas) para mostrar que conocen el uso de discurso directo en sus textos. En sus narraciones los niños mostraron poco uso de signos de puntuación tales como el punto y las mayúsculas.

Palabras clave: Procesos de lectoescritura en niños bilingües, la puntuación en los textos de los niños, desarrollo de escritura en contextos bilingües.

Introduction

Children writing development in Spanish and in English has been traditionally considered a difficult or problematic process to address by school teachers in their pedagogical practice. It may be due to the beliefs that teachers hold regarding the acquisition of two languages simultaneously by children. This exploratory study on bilingual children use of punctuation depicts the work children do when writing as a regular practice in a bilingual teacher's classroom in Tucson, Arizona.

Similar work that promotes the development of readers and writers in two languages has been carried out in public schools in Bogotá by Clavijo and Torres (1998), with third grade children native speakers of Spanish writing in English as a foreign language. Their language development as readers and writers in both Spanish and English was registered and analyzed to illustrate children language development in a literate environment that provides opportunities for children to become readers and writers in the two languages.

Additionally, Ruiz, (2004), carried out research to observe the process that second grade children developed as writers of stories, messages and reports in a private school setting, and Clavijo and Quintana (2003) developed a study to register how language teachers and children, at all educational levels, became writers of hyperstories3 in English and in Spanish.

The studies mentioned above contribute to contextualize the discussion about children development of punctuation by comparing the need that both populations of children in Tucson, Arizona and in Bogotá, Colombia have of becoming readers and writers in two languages. This educational need that all learners have of becoming literate can be addressed by school teachers who are readers and writers themselves interested in providing rich literate environments with many opportunities for children to interact with print in different ways and to connect meaningful literacy experiences from home and school.

Context for the study

This exploratory study on bilingual children use of punctuation was motivated by our interest to explore how different or similar the writing of bilingual children could be from the writing of monolingual children. Our research interest was nurtured by the reading of Ferreiro et. al. (1996) book "Caperucita Roja aprende a escribir: estudios psicolinguisticos comparativos en tres lenguas". It generated an academic dialogue around physical aspects of texts written by children such as segmentation, repetition, orthography and punctuation.

Thus, our study replicated Ferreiro's work done to explore the use of punctuation by children native speakers of Spanish, Italian and Portuguese in a different context. As mentioned before, we were interested in observing how bilingual children were learning the orthographic system of Spanish and how they used it in their writing.

Our research approach was concentrated on the close observation of children writing of the story of Little Red Ridding Hood in Spanish in order to document it and study the occurrence of punctuation in their texts as one of the aspects studied by Ferreiro et.al.

Setting

The physical context in which the study was developed was a public school in Tucson, Arizona located in the southeast part of the city. The bilingual community in Tucson recognizes the school as using innovative methods for teaching monolingual and bilingual children and considers that although the education policies changed for all the schools in the state of Arizona since 20004, the teachers in this school still value the multicultural and bicultural richness inherent to learning and speaking more than one language.

The school possesses important didactic resources for the development of reading and writing programs, arts, and music. The school also has a library with an extensive collection of books in English and in Spanish. About 2,500 books circulate monthly for an average of eight books per child. The figures indicate the high literacy practices related to reading books and meaningful writing activities that children in the school have that may benefit their reading and writing development.

Having described the context of the school and the type of literacy practices children experienced as part of their learning, we want to describe the participants and also to illustrate the steps followed in the visit to the classroom.

Participants

The students

In the bilingual classroom we visited there were twenty students. Nine were second graders and eleven first graders. Out of the twenty students, there were eleven girls and nine boys. Ten of them were predominantly speakers of Spanish and the other ten spoke English as their predominant language.

The researchers

During the semester that the study was developed (Spring, 1998) we were doctoral students in the program on Language, Reading and Culture of the School of Education at the University of Arizona. This exploratory study was part of an advanced literacy course directed by Dr. Kenneth S. Goodman as one of our professors.

The three researchers are bilingual, fluent speakers of Spanish and English with previous teaching experiences in public and private schools and universities in our countries. Ann Freeman is North American, native speaker of English and fluent in reading, speaking and writing in Spanish. Andrea Garcia Obregon is Mexican, equally fluent in both Spanish and English. Amparo Clavijo Olarte is Colombian, also fluent in both languages.

The Teacher

The bilingual first-second grade teacher is North American and she had been teaching primary school children for many years in the State of Arizona. We met her in one of our graduate classes at The University of Arizona since she had been doing academic work and publications with our professors, doctors Kenneth and Yetta Goodman for several years.

Procedures for data collection and analysis

As researchers we spent one full day in the classroom with the students and several sessions with the teacher to share our understandings about the data collected and to obtain additional information related to the regular classroom learning and teaching dynamics and insights about the bilingual program. As a research group we met several times during the week for three months to analyze the data and to write the paper with the final results.

The initial steps included gaining access to the bilingual classroom through the contact with the bilingual teacher at the University, proposing to her the writing activity with her class, meeting to share our evolving understandings of Ferreiro et.al (1996) book Caperucita Roja aprende a escribir and constructing the research questions that would direct our study.

Once the teacher agreed to have us develop the project in her class, her students were invited to participate in it by writing the story of Caperucita Roja. During all the classroom and research activities the teachers was very friendly and helpful to us and to the children. She introduced us to her class and helped us become familiar with her classroom physical and learning environment. When explaining the activity to the children she placed special emphasis on their ability to write in any of the two languages they know to show their competences as bilingual children.

After her introductory explanation to the students, we devoted our time to observe children process of writing for the whole class session. Although the students were asked to write their stories individually, as we moved through the room we observed they naturally began constructing their texts through social interactions. We could see collaboration among students who seated at the same table.

As the writing went on, students moved freely through the room seeking feedback from their peers and the adults in the classroom. While students were seeking assistance with their content and spelling, English speaking children sought the assistance of Spanish speakers for translation.

Once the students were finished writing we collected their pieces and asked a few of the children to read to us for transcription of their text. We then made photocopies of the written samples and left the school to start reading and analyzing the data as a group. Prior to reading the children's samples we made a list of the aspects of their writing we wanted to analyze. A list of five aspects resulted from our talking but it later had to reduced to two aspects only to be able to look at them in depth.

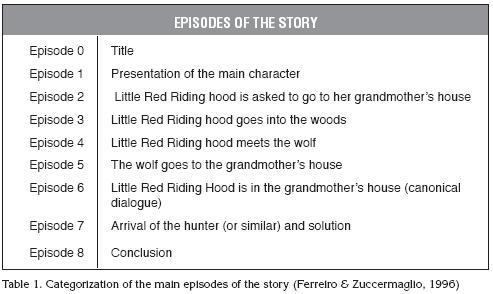

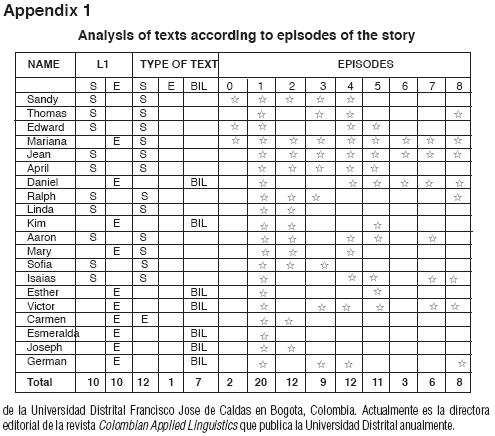

We decided to analyze the children's writing by looking at the content and the punctuation used in their stories. Our analysis was guided by an article by Ferreiro & Zucchermaglio (1996) who analyzed the writing of the story of Caperucita Roja by Spanish speaking children as part of a preliminary study for their book. They classified eight episodes in the story and looked at punctuation as present in dialogue (quoted speech) vs. narrative (See Table 1). Their criteria seemed appropriate to us so our next step was to write the questions we wanted to address in our study.

We aim at responding the following research questions:

-

Which characteristics emerged in bilingual children's writing of the story of Caperucita Roja?

-

How are they different or similar from the writing of monolingual Spanish speakers?

-

Are there any graphic/visual features in the writing of bilingual first/ second graders that shows awareness of punctuation?

-

How do these writers distribute punctuation marks in their texts (narrative and quoted speech) throughout the story?

Before establishing our criteria for the selection of the stories, we read and transcribed the stories together. As we did this, we classified the stories according to language by color coding the transcriptions. We found texts that were written solely in Spanish, texts written only in English and bilingual texts.

Bilingual texts were characterized by the presence of both Spanish and English. There were various combinations of these two languages. Some students began to write in Spanish, but included some vocabulary words in English. Other bilingual texts began with Spanish, and then switched completely to English. It is interesting to note here that within the bilingual and Spanish texts we found that several students used grammar and syntax of English with Spanish vocabulary.

Once having organized the texts by language, we decided to identify the number of episodes in the stories (See appendix 1). Because we were working with younger children than those in the study done by Ferreiro and Zuccher-maglio (1996), we decided that we would have enough information to work with if the stories we included had more than two episodes in them because we considered that we could observe punctuation in two episodes.

From the twenty writing samples collected, only five of them did not meet the criteria aforementioned. Of these five samples, four of them were produced by first grade students (three English dominant, and one Spanish dominant). The fifth was the writing of an English dominant second grader, who struggled for a long time trying to write his story in Spanish before switching to English. Time was an important factor for him because from his writing we could tell that he knew the story and could have written more if only he had been given more time.

Data analysis

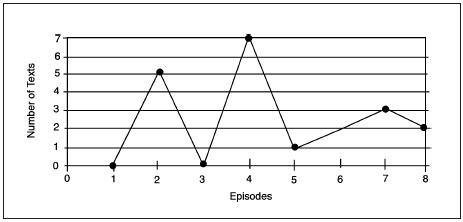

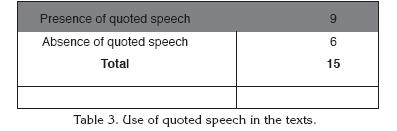

Our remaining data analysis is based on the 15 written samples which met the established criteria. We started by looking for quoted speech in relationship to the episodes. We assumed that we would find quoted speech within episodes 2,4,6 and 7, where more than one character was involved in the scene. This is confirmed with our data in Graphic 1. Our finding is consistent with Ferreiro and Zucchermaglio's hypothesis that the majority of quoted speech is found in these four episodes. Ferreiro and Zucchermaglio (1996), described quoted speech as "a dialogic form in which the speakers alternate" in the text (p.179). We adopted that same concept for our analysis.

As we identified quoted speech throughout the episodes of the story, we discovered that these areas had the most evident use of punctuation. This confirmed what Ferreiro and Zucchermaglio (1996) mentioned about the early use of punctuation marks within texts.

We found that nine out of fifteen children used quoted speech in their texts when writing their story of Caperucita Roja. The remaining six children in our sample did not use any type of dialogic form in their texts.

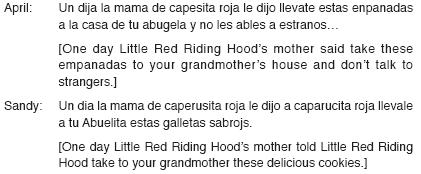

As we stated earlier, the children we worked with were younger than those described in the Ferreiro and Zucchermaglio (1996), study, so we considered that their punctuation development would not be as far along. Furthermore, what we counted as quoted speech when analyzing their texts did not always include traditional punctuation marks. Children like April and Sandy5, used quoted speech evident in the syntactic organization of their texts without using punctuation marks to denote it. We considered their use of quoted speech because their text organization tells about their awareness of using quoted speech. However, they still do not know how to represent the marks visually (graphically) in the text. The following excerpts serve as examples:

Although neither April nor Sandy use quotation marks to punctuate these sections of dialogue, it is clear that the characters in their story are speaking.

One form to represent dialogue in their text was the use of imperative forms such as take to your grandmother these delicious cookies.

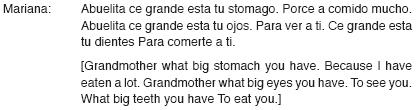

In addition to the use of the imperative as a wafy to indicate quoted speech another lexical solution used by these students was the use of turn-taking to indicate which character was speaking. This is illustrated in episode 6 of Mariana's text:

Not only does Mariana use turn taking in this episode, but she also uses periods. In all but the last exchange between Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf shown here, there is a period separating each character's speech. In the case where she did not insert a period, she began the "To eat you." with a capital letter.

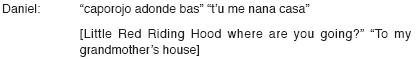

Some students, such as Daniel, did use traditional quotation marks when writing quoted speech.

Although Daniel does not use a question mark nor a period, his quotation marks clearly show a distinction between the two character's speech. Another very interesting use of punctuation used by Daniel throughout his story was his invention of "T'u". He uses it in sentences which include possessives. Clearly, this graphic representation demonstrates how the knowledge of both English and Spanish grammar interact in the process of becoming bilingual.

Conclusions

By revisiting our initial four questions, we are able to describe the conclusions of this study:

Question 1: which characteristics emerged in bilingual children's writing of Caperucita Roja in Spanish?

Some of the characteristics of the process of writing the story of Caperucita Roja, were related to the tensions experienced by some students when confronted to put their thought down in Spanish. In our examination of the written products, it was clear that we were working with a bilingual group in that the presence of both Spanish and English was displayed in their work.

Question 2: How are they different or similar to the writing of monolingual Spanish speakers?

The monolingual Spanish speakers in our study did not have to choose between the graphic and orthographic systems of the two languages as they set out to write their story. Regardless of their first language, or their language used to write their texts, we can say that most children in our study are in the process of internalizing the notion of punctuation. Further observation is necessary to determine how children deal with their developing concepts of punctuation.

We can also speculate that the children we worked with in this study had more contact with print and books than the monolingual students in the original study. Because both the school and the classroom have libraries with an abundance of books, we know that the students we worked with had a great deal of access to literature as a source for learning.

Question 3. Are there any graphic/visual features in the writing of bilingual first/second graders that show awareness of punctuation?

Clearly the majority of the students in our study were becoming increasingly aware of punctuation. Several stories included the use of periods, capital letters and spacing. In one of them the use of apostrophe was evident. A few students used an asterisk to indicate that they were moving from Spanish into English in their writing. When told that their writing time was over, one student quickly added a question mark to the end of her story to indicate that she had not finished.

Question 4. How do these writers distribute punctuation marks in their texts (narrative and quoted speech) throughout the story?

We found a direct correlation between the use of punctuation and the presence of quoted speech. Therefore, we believe that the students who included some time of punctuation in their stories, are aware of the dialogic function of quoted speech. We also know that there were additional forms (syntactic and lexical) used by children to show awareness of the use of quoted speech in their texts.

Implications for classroom teaching

One of the most striking observations we noted while watching the students' writing process, was the importance of socialization in learning and developing the notion of punctuation. Not only did we observe students helping each other at their tables, but we also encountered pairs of students who were later told, consistently to work together. We observed two dyads, Mariana and Jean, and Daniel and Victor. Vigotsky's (1978) idea of a zone of proximal development was clearly illustrated in the bilingual classroom. As the students were engaged in social interaction, they were able to push each other to advance in their writing development.

Implications for preservice and inservice teacher education

Regarding the education of prospective and experienced teachers we strongly believe that field experiences that help raise teachers' awareness of the importance of observing and understanding to respect the process children go through when learning to read and write in one or two languages should become a key aspect in preservice and inservice teacher education.

Teaching teachers how to become kid watchers is yet another avenue to make practitioners aware of the multiple classrooms situations that develop as children learn to learn. The basic assumption in kidwatching for Yetta Goodman (1996) is that development of language is a natural process in all human beings. She explores two important questions through kidwatching: "(1) what evidence is there that language development is taking place? and (2) when a child produces something unexpected, what does it tell the teacher about the child's knowledge of language?" (p.214).

Goodman's invitation to observe the teaching and learning processes carefully and to search for evidences of language development in classrooms by observing kids use language meaningfully, contributes to establish the link between practice and research. In this regards, Freeman (1998) considers that both teaching and researching have common aims. Thus, it is necessary for teaching and researching to converge since both are concerned with processes of building knowledge.

Furthermore, we consider that it is necessary to continue expanding teachers' understanding in the fields of literacy and biliteracy development by building local knowledge that allows them to respond to the questions that result from their teaching practice. We believe that classroom projects that promote teacher collaboration may help respond their daily inquiries and, at the same time, lead to innovations and transformations of traditional views and practices that define reading and writing as difficult or problematic processes6. There is also an urgent need to view literacy as one of the possibilities to empower students as learners in all the areas of the curriculum, to motivate them to use their full potential to be able to participate in all the literacy events that schools and the technologies of information and communication offer them daily.

Finally, this exploratory study of bilingual children use of punctuation aimed at raising teachers' awareness about the need to support students' writing development of the two languages being learned as teachers immerse them in lots of reading and writing activities. Specifically, by observing carefully the processes children follow when acquiring the graphic and orthographic systems of a language.

Two questions emerge at the end of this study that may guide further research:

How different is the situation of writing development of bilingual children in Colombia from that of bilingual children in Tucson, Arizona?

How do teacher education programs address the issue of students' literacy and biliteracy development with preservice and inservice teachers from their ownliteracy experiences?

Endnotes

1El contenido de este artículo fue presentado como ponencia por una de las autoras en el Segundo Simposio sobre Bilingüismo y educación Bilingüe en la Universidad del Valle en Cali, Colombia en Septiembre de 2002.

2The classrooms that include children from first and second grade are part of the multigrade, multiage structure of some classrooms in schools in The United States. In these classrooms teachers address the curricular contents of each grade level according to the learning needs of students.

3 Hyperstories are defined as the texts written by students that may include audio, text, graphics, and/or video. Students' narratives are characterized by the connections that each one of the components of the story (or narrative) has with other components. In the electronic format these connections are called hyperlinks.

4Proposition 203 eliminated most bilingual programs in the State of Arizona. The readers can refer to web page http://www.ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/JWCRAWFORD/az-unz.htm for further reading.

5The names of children used in this study are pseudonyms to protect the identify of participants.

6Clavijo's et.al. (2004) article: "Teachers acting critically upon the curriculum: innovations that transformed teaching" describes the processes of innovation in the language and literacy curriculum that fifty public school teachers carried out in their schools in Bogotá, Colombia.

Bibliography

Clavijo, A., N. Duran, Carmen H. Guerrero, Maribel Ramirez, Claudia Torres Jaramillo, Esperanza Torres, and Janeth Velasquez G. (2004). Teachers Acting Critically Upon the Curriculum: innovations that transformed teaching. Ikala. 9. No. 15. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia (in press). [ Links ]

Clavijo, A. y Torres, E. (2003). Aprendiendo a Enseñar Ingles a Niños. Manual de formación de docentes de Ingles como Lengua Extranjera. Bogotá: Craftman Editores. [ Links ]

Clavijo, A. (Ed.) (2001). Innovaciones pedagógicas en el área del lenguaje. Bogotá: ARFO Editores. [ Links ]

Clavijo, A. & Torres, E. (1998). La lectura en primera y segunda lengua: un proceso, dos idiomas. Lectura y vida. 3. 33-41. Buenos Aires, Argentina. [ Links ]

Clavijo, A. and Quintana. A. (2003). Creación de hiperhistorias: una estrategia para promover la escritura. Ikala. 8, No.14. 59-78. Medellin: Universidad de Antioquia. [ Links ]

Ferreiro, E. (2003) The present and past of the verbs to read and to write. Toronto: Ground-wood Books/Douglas & McIntyre. [ Links ]

Ferreiro, E. (1991). La construcción de la Escritura en el Niño. Lectura y Vida. 3. 5-14. Buenos Aires, Argentina. [ Links ]

Ferreiro, E., Pontecorvo, C, García, H. & Ribeiro, N. (1996). Caperucita aprende a escribir: estudios psicolinguisticos comparativos en tres lenguas. Barcelona: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Ferreiro, E. & Zucchermaglio, C. (1996) Children's use of punctuation marks: The case of quoted speech. In C. Pontecorvo, M. Orsolini, B. Burge, & L. Resnick (Eds.) Children's Early Text Construction. Moahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing Teacher Research. Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers. [ Links ]

Goodman, Y. (1990). (Ed.). How children construct literacy. Newark: International Reading Association. [ Links ]

Goodman, Y. (1996). Notes from a kidwatcher. Porstmouth: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Jolibert, J. (1998). Formar niños productores de textos. Santiago de Chile: Dolmen Ediciones. [ Links ]

Jolibert, J. (1992). Formar niños lectores de textos. Santiago de Chile: Dolmen Ediciones. [ Links ]

Perez, B. and Torres-Guzman, M. (1992). Learning in two worlds: an integrated Spanish/ English biliteracy approach. New York: Longman. [ Links ]

Ruiz, N.C. (2004), Watching kids develop as writers. Unpublished Masters thesis. Bogota: Universidad Distrital Francisco Jose de Caldas. [ Links ]

Spangenberg-Urbschat, K. and Pritchard, R. (1994). Kids come in all languages. Newark: International Reading Association. [ Links ]

Teberosky, A. (1996). Una lectura sobre "Caperucita Roja Aprende a Escribir. Lectura y vida. 4. 55-60. Buenos Aires, Argentina. [ Links ]

Vigotski, L. (1978). The prehistory of written language. Mind in Society: Boston: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

E-mail: aclavijo@andinet.com

E-mail: aclavijo@andinet.com