Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Criminalidad

versão impressa ISSN 1794-3108

Rev. Crim. vol.61 no.2 Bogotá Mai/Ago 2019

Estudios Criminológicos

Criminal desistance in Chilean women who have been deprived of liberty

1Doctor en Psicología Académico, Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de La Frontera Temuco, Chile ricardo.perez-luco@ufrontera.cl

2Magíster en Psicología Jurídica y Forense Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de La Frontera Temuco, Chile, v.chitgian01@ufromail.cl

3Doctor en Psicología Académico, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile, deciomettifogo@gmail.com

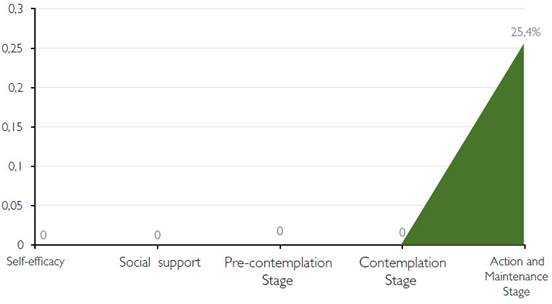

Diverse investigations have studied the phenomenon of criminal desistance in women, evincing characteristic factors for this population. The objective of this study was to explore a predictive model of the female criminal desistance from the psychosocial factors, self-efficacy, perceived social support and stage of motivation to change. Work was done with a group of 50 women who had been sentenced to deprivation of liberty punishments in Santiago, Chile. All of them participated in semi-structured interviews and gave an answer to self-report questionnaires, creating a database of characterization of the criminal process, identifying specific factors that permitted create a female desistance index. By means of multiple linear regression the aim was to determine the predictor variables, finding two profiles with different probabilities of desistance from the crime; likewise, the stages of action and maintenance explain a 25.4% of the desistance, showing the relevance of the will and the capacity of agency in the change process of the women who have infringed the law. This permits to propose the incorporation of the motivational approach in the interventions with women who have been detained and to further deepen in the found profiles.

Key words: Desistance; motivation to change; social support; female delinquency; Self-efficacy

Key words: Desistance; motivation to change; social support; female delinquency (source: Tesauro de política criminal latinoamericana - ILANUD). Self-efficacy

Diversas investigaciones han estudiado el fenómeno del desistimiento delictual en mujeres, evidenciando factores característicos para esta población. El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar un modelo predictivo del desistimiento delictual femenino, a partir de factores psicosociales, autoeficacia, apoyo social percibido y etapa de motivación al cambio. Se trabajó con un grupo de 50 mujeres que habían sido condenadas a penas privativas de libertad en Santiago, Chile. Todas participaron de entrevistas semiestructuradas y dieron respuesta a cuestionarios de autoinforme, creando una base de datos de caracterización del proceso delictual, identificando factores específicos que permitieron crear un índice de desistimiento femenino. Mediante regresión lineal múltiple se buscó determinar las variables predictoras, encontrándose dos perfiles con diferentes probabilidades de desistir en el delito; asimismo, las etapas de acción y mantenimiento explican un 25.4% el desistimiento, mostrando la relevancia de la voluntad y la capacidad de agencia en el proceso de cambio de las mujeres que han infringido la ley. Esto permite proponer la incorporación del enfoque motivacional en las intervenciones con mujeres que han estado recluidas y seguir profundizando en los perfiles encontrados.

Palabras clave: Desistimiento; motivación al cambio; apoyo social; delincuencia femenina; Autoeficacia

Diversas investigações têm estudado o fenómeno da desistência do crime em mulheres, evidenciando fatores característicos para esta população. O objetivo deste estudo foi explorar um modelo preditivo da desistência criminal feminina, a partir de fatores psicossociais, autoeficácia, apoio social percebido e etapa de motivação à mudança. Trabalhou-se com um grupo de 50 mulheres que têm sido condenadas a penas privativas de liberdade em Santiago, Chile. Todas participaram de entrevistas semiestruturadas e deram resposta a questionários de auto-relatório, criando uma base de dados de caracterização do processo delitivo, identificando fatores específicos que permitiram criar um índice de desistência criminal feminina. Através de regressão linear múltipla buscou-se determinar as variáveis preditoras, encontrando-se dois perfis com diferentes probabilidades de desistir no crime; do mesmo modo, as etapas de ação e manutenção explicam um 25.4% a desistência, mostrando a relevância da vontade e a capacidade de agência no proceso de mudança das mulheres que têm infringido a lei. Isto permite propor a incorporação do enfoque motivacional nas intervenções com mulheres que têm ficado recluídas e seguir aprofundando nos perfis encontrados.

Palavras chave: Desistência; motivação à mudança; apoio social; delinquência feminina; Autoeficácia

Introduction

At this time, according to the national public opinion poll, the delinquency is one of the main problems that requires been addressed by the government (Center of Public Studies, 2017). At the same time, Chile occupies the second place on the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] with a high rate of incarceration, 234 deprived of liberty per one hundred thousand inhabitants. Of these, the 8.6% corresponds to women (World Prison Brief, 2017), in whom the delicts prevail by the drugs law (47.6%) and law against the property (31.4%) (Chilean Gendarmerie, 2017).

The female delinquency has had an important rise, where more than 714.000 women and girls are in penal institutions throughout the world, showing an increase over the 50% since 2000 (Walmsley, 2017). In Chile, the increase has been 2.14 percentage points, considering that in the 2000 the female penal population was constituted by a 6.71%, while in July 2018 there is an 8.85% of women that are deprived of liberty (Chilean Gendarmerie, 2018). Even if it looks like a minor value, this produces a great impact in the population, because if one takes into account that 91% of the women serving sentence are mothers (“Fundación Paz Ciudadana” - Citizen Peace Foundation, 2015), they represent a higher social cost, due to its role and function in the childhood development (Block, Blockland, Van der Werff, Van Os & Nieuwbeerta, 2010).

The criminal behavior is understood as a multi-dimensional and multi-causal construct that integrates diverse factors at the criminal beginning, persistence, desistance and recidivism, which differs on men and women (Gobeil, Blanchette & Stewart, 2016).

The feminist perspective, regarding delinquency, raises that from the differential socialization of the genders there are specific factors for the criminal linkage (Belknap & Holsinger, 2006) and the criminal desistance of the women in the spheres: individual, family and social (Rodermond, Kruttschnitt, Slotboom & Bijleveld, 2015).

In the individual area some investigations identify that the early start of the puberty (regarding psychosocial characteristics) and the low intelligence quotient, can be predisposing factors for the criminal linkage. In the family sphere, one can appreciate that the presence of a severe discipline, the parental instability and count on biological parents that present offender practices also come into play in the beginning of the antisocial path. Likewise, this profile is characterized by to live stories of maltreatment and victimization, sexual abuse experiences, unexpected changes or crisis throughout its life history (moving home, not count on a stable place to live, losses of significant adults), linkage with older men and which present offender practices, school failure that can trigger an escalation process in the criminal involvement, drugs abuse, problems of mental health and risky sexual behaviors (Añaños-Bedriñana & García-Vita, 2017; Loinaz & Andrés-Pueyo, 2017; Turbi & Llopis, 2017).

The desistance theory seeks to explain why the people quit crime (Maruna, 2004; Nakamura & Bret Bucklen, 2014). It is understood as a process that involves behavior, cognitive, emotional and relational changes (Emaldía, 2015) where the evolutionary stage, the personal maturity (Rocque, 2015), the social links and the narrative, subjective and individual constructions facilitate the cessation of the criminal behavior (Mettifogo, Arévalo, Gómez, Montedónico & Silva, 2015).

The desistance is raised as an unusual dependent variable due to Maruna (2004) categorizes it in three spheres: cognitive, when the person explicitly expresses its desire of change; behavioral, manifesting itself in a decrease of the frequency and severity but with an increase in the variety of offences; two spheres, in which the primary desistance is inscribed, that give an account of a temporary cessation of the criminal activity. And a third sphere, the axiological, in which the secondary desistance occurs, producing a rupture or de-identification with the criminal past of the subject, to make way to the conformation of a way of life and conventional identity, away of the criminal sphere and matched to the prevailing regulatory social system.

In the article of Rodermond et al. (2015), 44 studies are reviewed about desistance in women, identifying that the theory is applicable to both men and women, but raises that differences according to gender exist, since having children, counting on supporting relationships, having economic independence and not presenting drug consumption are factors with the highest incidence in the female desistance. Also, they found that the low economic incomes, the family and household responsibilities, and victimization stories characterize the female population above the male one, which is concordant with the approaches of the feminist criminology (Yugueros, 2013).

Within the individual factors of the female desistance (Rodermond et al., 2015) is possible to appreciate that the capacity of agency and the level of self-efficacy can be related to the severity of the punishment, due to the strategies that the women develop to avoid it. Even Olavarría and Pantoja (2010) raise that the longest sentences have a reducing effect in the recidivism. Now, the decision to end the criminal career also can be influenced by the religiosity and/or spirituality; the handling of the rage in the field of the mental health; the abstinence from the drugs caused by being in prison; and the economic independence.

In the family factors Rodermond et al. (2015) highlights the couple relationship (pro-social) long and of good quality (not necessarily marriage) (Barr & Simons, 2015). The sons constitute a key factor when the woman presents the desire to be mother, perceives the advantages to form family and the motherhood is given in a late period of her life (Álvarez, Bustamante & Salazar, 2017; Monsbakken, Lyngstad & Skardhamar, 2013; Zoutewelle-Terovan, Van der Geest & Bijleveld, 2014). For its part, Martí and Cid (2015) found that the linkage with the couple and the parents, who constitute the strongest family ties favor the desistance inasmuch as they are prosocial and healthy relations, since, if the members present criminal conducts, the risk of recidivism increases.

Regarding to the social factors (Rodermond et al., 2015), one appreciates the work as a protective factor that prevents the commission of new crimes (Shepherd, Luebbers & Ogloff, 2016); likewise, the relations of pro-social friendship that provide support and accept the identity of the woman not linked to the crime, facilitate high levels of satisfaction and company.

The integral model of Cid and Martí (2011) incorporate the individual and social factors in a continuous process that ends in the criminal desistance (Padrón, 2014) and raises two relevant constructs: transitional factors and narratives of change (Mettifogo et al., 2015).

The transitional factors (Cid & Martí, 2011) allude to three specific variables: social support, social links and learning. The first refers to the institutions or people that can facilitate the reintegration processes, providing the material and/or emotional resources and favoring the level of pro-social self-efficacy of the subject (Bustamante, Álvarez, Herrera, & Pérez- Luco, 2016) and the conventional sense of belonging (Fox, 2015). The social links are associated to the establishment of new relations and/or assessment of the preexisting ones, according to the traditional role that is assumed in each one of them. Lastly, the learning is the break of the criminal habits and the forming of new pro-social practices, considering the costs and risks of the criminal activity (Maruna, 2004).

The narratives of change add two relevant concepts: identity and self-efficacy. The first is associated to the rupture with the criminal life style and the forming of a project of pro-social life; and the self-efficacy, term used by Bandura (Garrido, Herrero & Masip, 2005), when the person feels capable to overcome the obstacles to abandon the criminal activity (Cid & Martí, 2011).

For the purpose of this investigation, the female criminal desistance incorporates two variables from the integral model of Cid y Martí (2011), on the one hand, the social support (transitional factor) and on the other, the self-efficacy (factor associated to the narrative of change). Furthermore, one raises that at the base of any process of change a motivation exists that pushes the cognition to the action, which can be described through the transtheoretical model of Prochaska and DiClemente (Redondo & Martínez, 2011).

The purpose of this study is to determine the relation that exists between psychosocial factors, self-efficacy, perceived social support and stage of motivation to change, with the process of criminal desistance that presents a group of women that have completed sentence deprived of liberty in the Metropolitan Region of Chile.

Study the female criminal phenomenon has political relevance, while the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights of Chile recommends a transversal gender approach applying diverse regulations to which Chile meets, as the United Nations rules for the treatment of women prisoners and noncustodial measures for women offenders (Bangkok Rules), the United Nations standard minimum rules for non-custodial measures (Tokio Rules) and Yogyakarta Principles regarding to the application of the international legislation of the human rights in relation to the sexual orientation and the gender identity (Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, 2017). This gives an account of the need to consider an approach of rights visualizing the particularities of the women that have infringed the law.

From a social approach, one has identified that this population presents high rates of social exclusion (“Fundación Paz Ciudadana” - Citizen Peace Foundation, 2015), among which one can highlight living in poverty conditions, having low levels of schooling and being under care of people with some kind of dependency, such as the sons, older adults or with disabilities (Wola, 2017). It is to be noted that in mid-2017, an 8% of the female national penal population of the closed system could neither read nor write, which corresponds to 343 women (Chilean Gendarmerie, 2017).

The feminine prisionization can have serious consequences for the family system, because in front of the absence of woman, it is possible that the dependent persons face situations of abandonment and marginality, increasing the probability to be linked to drug consumption or to illegal traffic networks (Wola, 2017). This point puts in evidence that the women constitute a primary source of support for its family system, standing out the desistance model raises that the indicator is important to generate the pro-social change.

The theoretical-practical relevance consists of providing to the time reduction of the sentences, because an 18.5% of the convicted women in Chile remains deprived of liberty between 5 and 10 years; nevertheless, in the evaluation carried out by the Gendarmerie professionals is stablished that a 46.2% of the female penal population presents a low criminal commitment, understanding like the “degree of criminogenic contamination or involvement that a subject presents regarding the dominant jail culture among the inmate population” (Chilean Gendarmerie, 2017, p. 13). This puts in evidence that it does not exist a model which allows evaluate and intervene the particularities of the women that commit crimes from a solid and coherent gender approach (Piñol et al., 2015).

Reasons of this lie in that historically the investigations and theories which search to explain the criminal behavior have been developed under an androgenic paradigm, where the focus has been put in the study of the male population, generating comprehensive models of the valuation of the criminal phenomenon without gender distinction. This because the female delinquency has been invisibilized, given that the studies were carried out by and for men (Gobeil et al., 2016; Pina, 2016; Yugueros, 2013), having a scarce quantity of articles or investigations that have addressed the specific thematic of the women (Piñol et al., 2015). Furthermore, the models based on the criminal recidivism are centered in the risk to commit a new crime (Velásquez, 2014), while the desistance is focused on those that favor the cessation of the criminal career.

In this way, the importance of understanding the particularities of the criminal phenomenon in the women will allow for generating evaluations and interventions in accordance with the profile; for this, it is relevant to ask oneself whether there is relation between psychosocial factors, levels of self-efficacy, perceived social support and stage of motivation to change with the process of criminal desistance in women that have served sentences deprived of liberty. To answer this question, one identifies three specifics objectives: 1) to characterize the sample, differentiating by psychosocial factors, levels of self-efficacy, perceived social support and stage of motivation to change; 2) to generate an index of criminal desistance; 3) to stablish a degree of association between levels of self-efficacy, perceived social support and stages of motivation to change and criminal desistance.

Method

This investigation is framed from a feminist epistemology (Blázquez, Flores & Ríos, 2012) carrying out a comparative, correlational and descriptive study (Hernández, Fernández & Baptista, 1991). For the collection and analysis of the information one used the semi-structured interview technique and questionnaires, complemented with field notes, synthesis memo and elaboration of devolution reports that allowed the counterchecking, thus validating the information gathered and facilitating a process of consciousness by the participants, as the gender perspective raises it (Ríos, 2012). The sample was composed by 50 women of Chilean nationality, which served time deprived of liberty in the Metropolitan Region of Chile, who agreed to participate in the investigation on a voluntary basis, signing previously an informant consent and answering at least one of the questionnaires.

It should be noted that the 50% of the sample was deprived of liberty at the moment of the interview, what will be called intra-penitentiary phase, the 30% was in liberty in a post-penitentiary stage and a 20% was serving sentence in a free environment, that is she wasb been deprived of liberty but currently she was in a different space, out of enclosure, since it counted on an intra-penitentiary benefit (going out on Sunday or Saturday, or controlled in free environment).

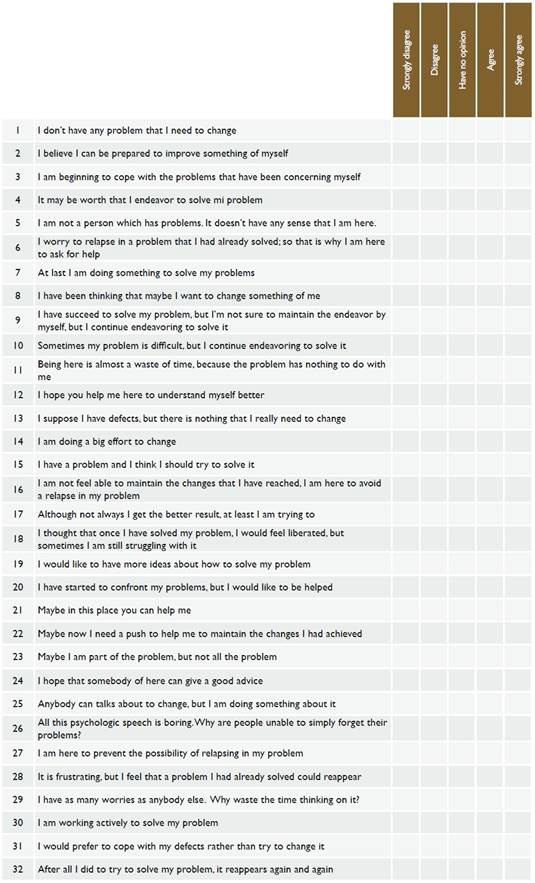

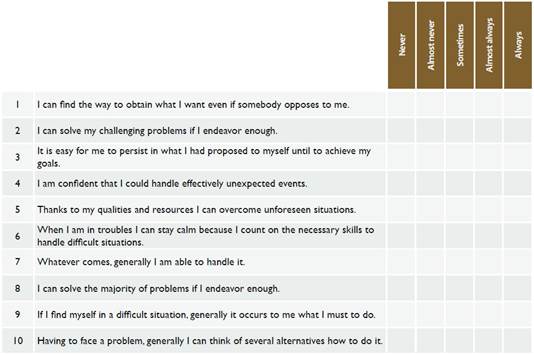

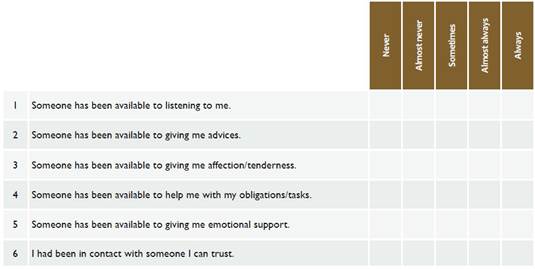

The instruments applied were: (a) an interview called “Criminal History”, created by the researcher and well-founded in the scientific literature (see appendixes), that allowed identify the psychosocial factors in the base of the start, maintenance and desistance of the criminal conduct; and three questionnaires of self-report in Likert format that presented an adequate reliability. (b) General Self- Efficacy Scale “GSE”; consists of 10 items that evaluate the perception that the person has regarding to its capacities to handle different stressing situations in its daily life (Cid, Orellana & Barriga, 2010), which obtained a Cronbach alpha of 0.899; it is to be noted that, for the purpose of this investigation, one made a change of the agreement degree (opinion) by frequency of the experience from never until always, maintaining the original 5 points. (c) ENRICHD Social Support Index (ESSI); counts on 6 items that measure structural, instrumental and emotional support (Ortiz, Myers, Dunkel, Rodríguez & Seeman, 2015), obtaining an alpha of 0.950. And (d) Stage of Change Scale (SOCS), with 32 items of statements or beliefs about the problem conduct that the person experiences (Redondo & Martínez, 2011), that obtained an alpha of 0.787. For the data analysis one used the SPSS software in its version 24.0.

Results

Characterization of the sample

The average age of the total of women that participated in the investigation (N=50) was 41.8 years, being 24 the minimum and 60 the maximum (SD=11). The level of schooling reached whose responded all the interview (N=49) is low; 41% has incomplete primary education and only a 29% finished the secondary education. A 55% has training in a trade. A 84% refers belonging to a religion; 56% from them is defined as catholic and 41% evangelical. A 47% refers having some type of consumption of substances; among them the 61% consumes cigarettes, the 35% marijuana and 4% cocaine. A 35% refers have been diagnosed with some mental health problem, being a 76% for mood disorders. A 51% manifested being in a relationship, 92% are mothers, 71% refers having any family member involved in crimes, being a 34% their parents and a 55% that is been done legal activities to generate economic incomes.

About the crime prevalence regarding to the total sample, the last crime committed is majoritarian by the drugs law (64%), followed by crimes against the property (20%), specifically thefts, and in a lower rate, crimes against the people and benefits breaches (8% each one).

To understand the phenomenon of the criminal practices in women that have been served sentences deprived of liberty, one identified psychosocial factors related at the beginning, maintenance and criminal desistance.

The average age of the criminal start was 25.4 years, with a minimum of 7 and maximum of 51 years (SD=13). The crime prevalence is still being the Drugs Law with 55.1%, followed by thefts in a 31%; a 28.6% of women refer having committed the crime for economic need, 20.4% did it for the sense of belonging to the peer group, and the same percentage manifests have done for a crisis in its life story, like its couple was detained and deprived of liberty; and a 14.3% says have done for the consumption of substances. Likewise, the way to get involved in a 28.6% was trough the peer group, a 24.5% did it with couple and there is a 12.2% that began together with a member of its family. The feeling that they refer in front of a crime commission is obtaining quick and easy money in a 28.6%; a 22.4% describes have felt adrenaline and power, while a 20.4% manifests guilt and regret for the committed crime. In this first opportunity, a 30.6% of women was sentenced with an alternative punishment of suspended sentence.

In this moment of their lives, they identify a close relationship with their families in a 67.3%, describing the child rearing by its parents or caregivers as protectors in a 42.9%, although there is a 40.8% that also identify them as negligent. Moreover, the 57.1% had deserted the school system, the 59.2% was mother and a 53.1% had a couple, where a 61.5% of them had offender practices. Likewise, a 73% of the women refer having consumed some type of substance along its life story, 26% of them consumed marijuana, other 26% ingested base paste of cocaine, a 20% did it with cocaine, a 17% drunk alcohol and, lastly, there is a 11% that consumed other type of substances like neoprene, opiates, etc. From the total of women which refer have consumed, a 77% identifies that was doing it daily.

All the elements described above match with many of the predisposing factors identified in different scientific investigations, like the school failure, count on parents that present negligent practices, couples that commit crimes, consumption of substances and precarious socioeconomic situation (Añaños- Bedriñana & García-Vita, 2017; Loinaz & Andrés-Pueyo, 2017; Turbi & Llopis, 2017), showing up the situations of vulnerability that those women have living, and that precede the deprivation of liberty.

Now, regarding to the process of maintenance in the criminal path, one appreciates a recidivism in the same crime of an 87.8%; in turn there is an 8.1% that refers have committed other type of crime, while a 4.1% refers not have re-offend. The motivation for maintaining in the crime in a 38.8% points to the same feeling of having quick and easy money described in the beginning of the offender practices. If one considers that the 54% had some alternative punishment to the conviction that it was not accompanied by a psychosocial process oriented to the social insertion and to the prevention of a new crime commission, it seems that the severity of the punishment does not reach having the effects oriented to the desistance as Rodermond et al. (2015) raise it.

Regard to the criminal desistance, one has identified five psychosocial factors described in the literature, such as, for example, adhere to a religion or have a spiritual belief, count with higher levels of schooling achieved and/or trainings, the abstinence from the substances consumption, the absence of problems in mental health and the economic independence, which are characteristics for the female population (Rodermond et al., 2015). In addition, those factors are conjugated with the constructs of self-efficacy, perceived social support and motivation to change, that have been studied as at the base of this process.

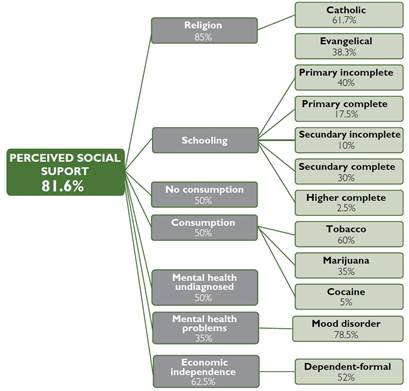

From the above, one appreciates there is an 83.6% of the women that score in high levels of self-efficacy, there is an 81,6% that perceives high levels of social support and a 36% is located in the stage motivation of action to change. In the figures the psychosocial factors are presented depending on the highest levels of the constructs described in the present investigation, due to, according to the base hypothesis, those would be oriented to the criminal desistance.

Figure 1. Characterization of psychosocial factors depending on the high level of perceived general self-efficacy.

Criminal desistance index

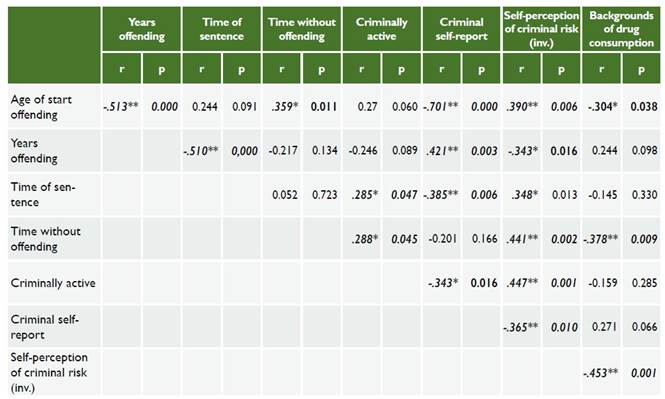

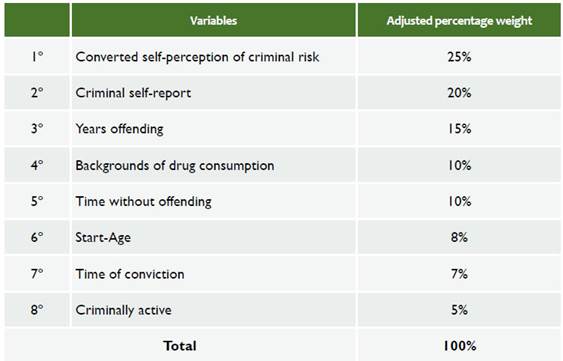

In order to construct the criminal desistance index, one explores variables related to the start, maintenance and decision to let committing crimes. In this occasion one raises the desistance as interval quantitative variable, where the higher the value obtained the higher level of construct presence.

The construction of this indicator was done based on the scientific literature that raises the existence of determined static and dynamic factors that influence in the criminal paths, which have been studied without gender distinction. The first are those that cannot be modified, therefore, they serve as backgrounds, although they are not intervened. For example, the start age is one of the scientific wealth the most studied, since it predicts the persistence of crime (Piquero & Moffitt, 2005). In that same perspective, the number of years committing crimes permits understand if the the criminal path is limited or persistent (Piquero & Moffitt, 2005), also understanding that longer the time the person is involved in offender practices, the greater the probability that a validation and selfefficacy of those conducts exists, which facilitates the forming of a criminal identity (Maruna, 2004). Following this model, the number of self-reported crimes also would be understood under a type of persistent criminal path. For the purpose of the indicator, the criminal self-report refers the number of crimes that the woman manifests she has committed along her criminal path, which was quantified in five intervals: (a) 1-5, (b) 6-10; (c) 11-15; (d) 16-20; and, (e) more than 20 crimes. Finally, the time of the last sentence of deprivation of liberty is a factor that is associated to the decreasing of the recidivism since it acts as recognition of the severity of the punishment and the persons avoid to happen again for the same situation (Olavarría & Pantoja, 2010).

In the dynamic factors one appreciates backgrounds of consumption of substances, which has an important incidence in the female recidivism (Karlsson 2013). For the construction of this indicator, one visualized according to the type of consumption, where one generated a scale from 0 to 8 (no consumption; tobacco=1; alcohol=2; marijuana=3; cocaine=4; cocaine base paste =5; pills=6; opiates=7; solvents=8). The active criminal commission reflects the absence of desistance and reiteration of conducts transgressing the law (Villagra, Espinoza & Martínez, 2014). In this perspective, one includes the self-perception of criminal risk, variable that is obtained from the Stage of Change Scale (SOCS), that is an item which raises: “Looking at myself, with an absolute sincerity I consider that the existing risk of return to falling in my problem, in a scale from 0 to 10 points, is (…) points, where 0 is a null risk and 10 a maximum risk”. A woman that remains criminally active should score a higher level in the risk of committing new crimes, which from the transtheoretical model of change would give an account of stages the most distant from the conductual change.

Finally, one raises a desistance variable “time without offending”, because the more extensive is it one infers the possibility to having live a process of primary desistance, that is defined as a period in which the criminal conduct is asleep, but that one has not generated yet the axiological change (Maruna, 2004). Actually, Droppelmann (2017) operationalizes the desistance as the absence of self-reported crimes for a period of one year crossing the information with official statistics of legal recidivism.

In synthesis, the eight factors selected to the construction of the indicator are: start age, years offending, number of self-reported crimes, time of the last conviction, consumption backgrounds, active criminal commission, self-perception of the criminal risk, and time without committing crimes.

In order to can creating the index, in the first place, one obtained the values for the eight indicators noted above for the 50 women. Subsequently, one carried out an analysis of bivariate correlation (see table 2) that shown the power of the associations between variables. Then, one took decisions based on the criterion of the researcher considering the literature studied, where one discriminated the variables according to its percentage weight (see table 2) and subsequently one converted the scores obtained in each variable according to those percentages, so that making a sum and obtaining the Criminal Desistance Index (CDI) for each participant.

Table 1 Hierarchy of variables according to the adjusted percentage weight.

Source: Own elaboration.

From this index one can determine two profiles with different probabilities of desist from crime. The first profile, a woman with greater probabilities of desist, is characterized for late start of the offender practices, lower time committing crimes, serving of larger convictions, longer periods without committing crimes, lower amount of self-reported crimes, and lower self-perception of risk to continue doing it, without backgrounds of substances consumption and without being criminally active. The second profile presents lower probabilities of desisting and is characterized for an early start in the crime, mainly in the childhood and pre-adolescence, greater time committing crimes, with a persistent criminal path, and greater number of self-reported crimes, possesses a self-perception of high risk to return to offend, serves shorter sentences deprived of liberty, it counts on more backgrounds of substances consumption and is criminally active.

Prediction of the female criminal desistance

The degree of association between the levels of selfefficacy, perceived social support, stages of motivation to change (pre-contemplation, contemplation, action and maintenance) and criminal desistance was obtained by means of a multiple linear regression model, which brought two models. Nevertheless, one appreciates that the second model presents better indicators of prediction of the desistance, which includes the stages of the motivation to change: action and maintenance. In this model, the criminal desistance is explained in a 50.4% by the identified variables; notwithstanding, once the value is corrected by the effect of the sample and of the independent variables, it turns out that the proposed model explains in a 25.4% the variable dependent of the criminal desistance.

Discussion

Responding to the objectives of this study, the characterization of the sample according to psychosocial factors evidence a profile with deep traces of discrimination and oppression, attributable to the condition of being woman (Norza-Céspedes, González-Rojas, Moscoso-Rojas & González-Ramírez, 2012), including social exclusion and history of infringements (Fundación Paz Ciudadana, 2015).

Complementing with qualitative data obtained from the interviews, one appreciates that the sample counts on low levels of schooling (69% have not ended the secondary education), where one identifies expressions as “they took me out (from the school) to care mi brothers” (R.C., 2017), which puts in evidence the school failure and with that a State which does not take charge of safeguarding the education rights of these girls and adolescents (Añaños-Bedriñana & García-Vita, 2017).

They present backgrounds of substances consumption, where it is stood out a 26% of prevalence of base paste of cocaine, which is reflected in the phrase “I was inside a house consuming base paste” (Y.E., 2017), that in turn it is concordant with numbers found in a recent study with women deprived of liberty in Chile (Centre of Studies Justice and Society, 2017).

One sums factors of family risk, as the 40.8% identifies parents/caregivers with negligent practices, and/or offender conducts (34%), manifested in the phrase “my dad is a thief” (C.V., 2017), which is a facilitator for the start of the criminal commission (Martí & Cid, 2015). Inside of the same line, one identifies that the 59.2% was mother at the moment of starting the offender practices, being one of their motivators for offend, reflected in the phrase “I robbed for my children” (A.B., 2017), due to the situations of socioeconomic vulnerability to whom she was exposed (Antony, 2014; Cárdenas & Undurraga, 2014), manifested in “we didn’t have to eat” (P.M., 2017). Among those who had couple, a 61.5% of them committed crimes, being a factor of risk for the linkage to the offender practices, which it is appreciate in the expression “my husband offered to me and I help him” (G.O., 2017) (Loinaz & Andrés- Pueyo, 2017).

This characterization puts in evidence the differences with male population (Ariza & Iturralde, 2017; Droppelmann, 2017), where motivations, needs and social control exercised by the dominant patriarchal structure are specific by gender.

Now, at the moment of the investigation interview, one appreciates that the average age was 41.8 years (SD=11), which gives an account of, according to the theory of the desistance, that the women would be in an evolutive stage oriented to the cessation of the criminal conduct (Maruna, 2004). From this starting point it can be explained that the sample presents high levels of general self-efficacy (83.6%), perceived social support (81.6%) and is in the stage of motivation of action to change (36%), which suggests a population in criminal desistance process (Cid & Martí, 2011).

One sums psychosocial factors related to the desistance (Rodermond et al., 2015), for example, practicing a religion (84% of the sample), not counting on abusive consumption or dependent of substances (53%), not presenting difficulties of mental health (65%), counting on training curriculum (55%) and having an economic independence (55% generates legal economic incomes).

Now, regarding to the objective of generating an index of criminal desistance, one identifies, with the eight indicators selected, two profiles with different probability of desisting. This profiling allows understand that, inside a same population, as the women deprived of liberty are, it exists heterogeneity, that in turn evidences the need of generating specialized and differentiated interventions according to the particularities of each profile. In this sense, the women which count on persistent criminal paths require a deeper approach in habits, self-efficacy, life style and antisocial identity (Piquero & Moffitt, 2005). Instead, the woman with lower criminal story requires specific opportunities that facilitate its reincorporation to the family and the job, promoting a sustainable social insertion.

In response to the last objective, the model of criminal desistance shows that the motivation to change, in their stages of action and maintenance, explains a 25.4% of the variance, evidencing the relevance that has the capacity of agency and the personal will in the process of cessation of the criminal conduct (Mettifogo et al., 2015; Rodermond et al., 2015).

From the above, it is necessary the incorporation of the transtheoretical model of the change in a transversal way in the programs that work with this population. In this way, one has a central axe oriented to promote the motivation to the desistance (Cid & Martí, 2011) and in a specialized way differentiated interventions according to the profiles found, bringing opportunities for the sustainability of change and working in an intensive mode in the axiological resignification of the behavior, to a life style socially adjusted. Additionally, the strategies of intervention have to be founded from a gender perspective, being specifics for women, as in their reparatory contents as in the construction of bridges of social inclusion.

Within the limitations of the study, there is the size of the sample, something characteristic of the investigation with female penal population, but also their characteristics, because one accesses to it with support of programs that work in social reinsertion intra and post-penitentiary, generating a bias to the criminal desistance, inasmuch as all of who accepted of participating voluntary were active or had been participated in any of those programs; this, nevertheless, is also one of the strengths of the study, because the focus was the desistance, not the recidivism.

By way of projection, it would be interesting to expand the sample to different regions of Chile in order to know whether the results are able to be extrapolated to other territories and if the profiles are changing. Likewise, one requires still studying the relation between the variables of self-efficacy and perceived social support with the criminal desistance, incorporating the specific elements related to the criminal sphere and considering the women who are not part of any social program. Finally, it is necessary to still investigating about the variable of motivation to change in the processes of intervention, in order to generate a differentiated, focused and specialized approach that facilitates the desistance and sustainability of the social reinsertion.

REFERENCES

ACNUDH: Alto Comisionado de Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos (1990). Reglas mínimas de las Naciones Unidas sobre las medidas no privativas de la libertad (Reglas de Tokio). Adoptadas por la Asamblea General en su resolución 45/110, de 14 de diciembre de 1990, disponible en esta dirección: https://www.ohchr.org/SP/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/TokyoRules.aspx [Accesado el 13 Abril 2019] [ Links ]

Álvarez, L., Bustamante, Y. & Salazar, M. (2017). Paternidad y su incidencia en el desistimiento delictual: una revisión teórica. Revista Criminalidad, 59(1): 65-75. [ Links ]

Antony, C. (2014). El desastre Humanitario. Revista Derecho penitenciario, 4: 1-42. Recuperado de: http://www.umayor.cl/mailing/2014/marzo/28-3-2014/revista-peni/descargas/revista- [ Links ]

Añaños-Bedriñana, F. T. & García-Vita, M. M. (2017). ¿Desarrollo humano en contextos punitivos? Análisis socioeducativo desde las vulnerabilidades sociales y el género. Revista Criminalidad, 59(2): 109-124. [ Links ]

Ariza, L. & Iturralde, M. (2017). Mujer, crimen y castigo penitenciario. Política criminal, 12(24): 731-753. [ Links ]

Barr, A. B. & Simons, R. L. (2015). Different dimensions, different mechanisms? Distinguishing relationship status and quality effects on desistance. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(3): 360-370. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000079. [ Links ]

Belknap, J. & Holsinger, K. (2006). The Gendered Nature of Risk Factors for Delinquency. Feminist Criminology, 1(1): 48-71. [ Links ]

Blázquez, N., Flores, F. & Ríos, M. (2012). Investigación feminista: epistemología, metodología y representaciones sociales. México DF: UNAM. [ Links ]

Block, C.R., Blockland, A. A., Van der Werff, C., Van Os, R. & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2010). Long-term patterns of offending in women. Feminist Criminology, 5(1): 73-107. [ Links ]

Bustamante, Y., Álvarez, L., Herrera, E. & Pérez-Luco, R. (2016). Apoyo social percibido y su influencia en el desistimiento delictivo: Evaluación del rol institucional. Psicoperspectivas, 15(1): 132-144. https://doi.org/10.5027/PSICOPERSPECTIVAS-VOL15-ISSUE1-FULLTEXT-627. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, A. & Undurraga, R. (2014). El sentido del trabajo en mujeres privadas de libertad en Chile. Cuestiones de género: de la igualdad y la diferencia, 9: 286-309. [ Links ]

Centro de Estudios Justicia y Sociedad, (CJS( (2017). Reinserción, Desistimiento y Reincidencia en Mujeres Privadas de Libertad en Chile: Informe de Línea de Base. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Santiago: Chile. [ Links ]

Centro de Estudios Públicos (2017). Encuesta CEP. Septiembre - octubre 2017. Estudio Nacional de Opinión Pública Nº 81. Recuperado de https://cepchile.cl/cep/site/artic/20171025/asocfile/20171025105022/encuestacep_sep_oct2017.pdf [ Links ]

Cid, J. & Martí, J. (2011). El procedimiento de desistimiento de las personas encarceladas. Barcelona: Centro de Estudios Jurídicos y Formación Especializada. [ Links ]

Cid, P., Orellana, A. & Barriga, O. (2010). Validación de la escala de autoeficacia general en Chile. Revista médica de Chile, 138(5): 551-557. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872010000500004. [ Links ]

Droppelmann, C. (2017). Housewife, mother or thief: gendered desistance and persistence from crime (documento de trabajo, no publicado). Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Santiago: Chile. [ Links ]

Emaldía, A. (2015). Desistimiento Delictivo e Identidad de Género: una aproximación desde los relatos de vida de mujeres. (Tesis para optar al grado de Magíster, no publicada). Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco, Chile. [ Links ]

Fox, K. J. (2015). Theorizing Community Integration as Desistance-Promotion. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(1): 82-94, https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854814550028. [ Links ]

Fundación Paz Ciudadana (2015). Exclusión social en personas privadas de libertad: Resultados preliminares. Recuperado de: http://www.pazciudadana.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/exclusion-social-resultados-preliminares.pdf [ Links ]

Garrido, E., Herrero, C. & Masip, J. (2005). Teoría social cognitiva de la conducta moral y de la delictiva. En Pérez, F. (Ed.). Serta in memoriam Alexandri Baratta (379-413). España: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Salamanca. Recuperado de: https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Pajares/GarridoEtAl2005.pdf. [ Links ]

Gendarmería de Chile (2017). Informe de Caracterización de Población Femenina en el subsistema cerrado y abierto. Elaborado para el Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos. [ Links ]

Gendarmería de Chile (2018). Estadísticas y Publicaciones. Recuperado de: http://www.gendarmeria.gob.cl [ Links ]

Gobeil, R., Blanchette, K. & Stewart, L. (2016). A Meta-Analytic Review of Correctional Interventions for Women Offenders Gender-Neutral Versus Gender-Informed Approaches. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(3): 301-322. https://doi.org/0093854815621100 [ Links ]

Hernández, R., Fernández, C. & Baptista, P. (1991). Metodología de la investigación. McGraw-Hill: México. [ Links ]

Karlsson, L. (2013). This is a Book about Choices: Gender, genre and (auto) biographical prison narratives. NORA-Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 2(3):187-200. [ Links ]

Loinaz, I. & Andrés-Pueyo, A. (2017). Victimización en la pareja como factor de riesgo en mujeres en prisión. Revista Criminalidad, 59(3): 153-162. [ Links ]

Maruna, S. (2004). Desistance from crime and explanatory style: a new direction in the psychology of reform. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 20(2): 184-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986204263778. [ Links ]

Martí, J. & Cid, J. (2015). Encarcelamiento, lazos familiares y reincidencia. Explorando los límites del familismo. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 73(1): 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/103989/ris.2013.02.04 [ Links ]

Mettifogo, D., Arévalo, C., Gómez, F., Montedónico, S. & Silva, L. (2015). Factores transicionales y narrativas de cambio en jóvenes infractores de ley: análisis de las narrativas de jóvenes condenado por la ley de responsabilidad penal adolescente. Psicoperspectivas individuo y sociedad, 14(1): 71-88. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos (2017). Política Pública de Reinserción Social. Recuperado de: http://www.minjusticia.gob.cl/media/2017/12/Politica-Publica-Reinsercion-Social-2017_vd.pdf. [ Links ]

Monsbakken, C., Lyngstad, T. & Skardhamar, T. (2013). Crime and the transition to parenthood: The role of sex and relationship context. British Journal of Criminology, 53, 129-148. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azs052. [ Links ]

Nakamura, K. & Bret-Bucklen, K. (2014). Recidivism, redemption, and desistance: Understanding continuity and change in criminal offending and implications for interventions. Sociology Compass, 8(4): 384-397. [ Links ]

Norza-Céspedes, E., González- Rojas, A., Moscoso-Rojas, M. & González-Ramírez, J. (2012). Descripción de la criminalidad femenina en Colombia: factores de riesgo y motivación criminal. Revista Criminalidad, 58(1): 339-357. [ Links ]

Olavarría, M. & Pantoja, R. (2010). Sistema de justicia criminal y prevención de la violencia y el delito, en Programas dirigidos a reducir el delito: Una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Documento de trabajo, Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID). [ Links ]

ONU: Asamblea General (2010). Reglas de las Naciones Unidas para el tratamiento de las reclusas y medidas no privativas de la libertad para las mujeres delincuentes (Reglas de Bangkok): Nota de la Secretaría, 6 Octubre 2010, A/C.3/65/L.5, disponible en esta dirección: https://www.refworld.org.es/docid/4dcbb0e92.html [Accesado el 13 Abril 2019] [ Links ]

Ortiz, M.S., Myers, H.F., Dunkel, C., Rodríguez, C.J. & Seeman, T.E. (2015). Psychosocial Predictors of Metabolic Syndrome among Latino Groups in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). PLoS ONE, 10(4): e0124517. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124517. [ Links ]

Padrón, M. F. (2014). Expectativas de reinserción y desistimiento delictivo en personas que cumplen penas de prisión: factores y narrativas de cambio de vida. (Tesis para optar al grado de magíster, no publicada). Universitat de Barcelona, España. [ Links ]

Pina, I. (2016). Criminología feminista. España: Universitas Miguel Hernández. Recuperado de http://crimina.es/crimipedia/topics/criminologia-feminista/. [ Links ]

Piñol, D., San Martín, J., Sánchez, M., Vistoso, C., Ramírez, A., Olivares, M. y Espinoza, O. (2015). Sistematización y lecciones aprendidas en la intervención con población reclusa femenina que favorezcan la reinserción. Chile: Subsecretaría de Prevención del Delito y Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública, Gobierno de Chile. [ Links ]

Piquero, A. & Moffitt, T. E. (2005). Explaining the facts of crime: How the developmental taxonomy replies to Farrington's invitation. En D. P. Farrington (Ed.), Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending (pp. 51-72). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. [ Links ]

Redondo, S. & Martínez, A. (2011). Tratamiento y cambio terapéutico en agresores sexuales. Revista Española de Investigación Criminológica, 8(9): 1-25. [ Links ]

Ríos, M. (2012). Metodología de las ciencias sociales y perspectiva de género. En Investigación feminista: Epistemología, metodología y representaciones sociales. Eds. Blázquez, Flores & Ríos. UNAM, México: pp. 179-197. [ Links ]

Rocque, M. (2015). The lost concept: The (re)emerging link between maturation and desistance from crime. Criminology and Criminal Justice, 15(3): 340-360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895814547710. [ Links ]

Rodermond, E., Kruttschnitt, C., Slotboom, A. M. & Bijleveld, C. (2015). Female desistance: A review of the literature. European Journal of Criminology, 13(1): 3-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370815597251 [ Links ]

Shepherd, S. M., Luebbers, S. & Ogloff, J. R. P. (2016). The Role of Protective Factors and the Relationship with Recidivism for High-Risk Young People in Detention. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(7): 863-878. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854815626489 [ Links ]

Turbi, A. & Llopis, J. (2017). Salud física y mental en mujeres reclusas en cárceles españolas. En F. Añaños (Ed.). En prisión. Realidades e intervención socioeducativa y drogodependencias en mujeres (pp. 71-86). Madrid: Narcea Ed. [ Links ]

Velásquez, J. (2014). Origen del paradigma de riesgo. Política Criminal, 9(17): 58-117. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-33992014000100003. [ Links ]

Villagra, C., Espinoza, O. & Martínez, F. (2014). La medición de la reincidencia y sus implicancias en la política criminal. Centro de Estudios de Seguridad Ciudadana, Instituto de Asuntos Públicos, Universidad de Chile. Recuperado de http://www.cesc.uchile.cl/Publicacion_CESC_web_creditos.pdf. [ Links ]

Walmsley, R. (2017). Women and girls in penal institutions, including pre-trial detainees/remand prisoners . World Female Imprisonment List, 4º Ed. Recuperado de: http://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_female_prison_4th_edn_v4_web.pdf [ Links ]

Wola (2017). Mujeres, políticas de drogas y encarcelamiento: Una guía para la reforma de políticas en América Latina y el Caribe. Recuperado de: https://www.wola.org/sites/default/files/Guia.FINAL_.pdf. [ Links ]

World Prison Brief (2017). World Prison Brief data: Chile. Recuperado de: http://www.prisonstudies.org/country/chile [ Links ]

Yugueros, A. J. (2013). La delincuencia femenina: una revisión teórica. Nueva época, 16(2): 311-316. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_FORO.2013.v16.n2.43943. [ Links ]

Zoutewelle-Terovan, M., Van der Geest, V. & Bijleveld, C. (2014). Associations in criminal behavior for married males and females at high risk of offending. European Journal of Criminology, 11(3): 340-360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370813497632. [ Links ]

Para citar este artículo / To reference this article / Para citar este artigo: Pérez-Luco, R., Chitgian-Urzúa, V. & Mettifogo-Guerrero, D. (2019). Criminal desistance in Chilean women who have been deprived of liberty. Criminality journal, 61(2): 101-112

Appendixes

Interview “Criminal history”

The objective of the interview is to know you better, know when you began to commit crimes and understand what occurred around you at this time, that is, who you associated with, what things you did, how you felt, etc., and also, what has currently changed.

The interview is not to judge you, neither to evaluate if what you have done is right or is wrong; it is to know you a little more, so tell me:

- How old are you?

- What is your date of birth?

- Do you remember when you committed a crime the first time?

- How old were you? or, the year when it was committed?

- Do you remember how it was? What did you do?

- Whom were you with?

- Did they catch you? Yes No

- Did you were formalized? Yes No

- Sentenced? Yes No

- How long?

- What made you do it? or, Why do you think you did?

- How did you felt this first time?

- Did you do again the same crime? Yes Why? No

- Did you do other type of crime? Yes Which one? No

- How was the relationship with your family at this time? (e.g.: you got along well with everybody, argued, fought, tender, were distant, you broke).

- How would you describe the way they raised you? (they were present, but they don’t let you do anything or rather, they were working and they didn’t set rules to you, or they weren’t)

- At this moment, did you have couple? Yes No

- Did he offend too? Yes No

- What types of crimes he performed?

- Did you have children? Yes How many? No

- Did you go to school? Yes What grade were you in? No Why?

- Did you consume any type of drug and/or alcohol? Yes Which one(s)? No

In case of you have not been sentenced the first time, one pass to the next question:

23.- When was the first time you were sentenced?

24.- How old were you? or, the year when it was committed?

25.- What crime did you commit in that opportunity?

26.- What was the sentence?

27.- Time of conviction?

28.- What was the last crime you committed?

29.- How old were you? or, the year when it was committed?

30.- Do you remember how it was? What did you do?

31.- Whom were you with?

32.- Did they catch you? Yes No

33.- Did you were formalized? Yes No

34.- Sentenced? Yes No

35.- How much time?

36.- What made you do it? or, Why do you think you did?

37.- Have you had periods without committing crime? Yes No

38.- What have you done to support you financially?

39.- For how long?

40.- Did you still committing crime currently? Yes No Why?

41.- How many crimes do you think you have committed along your life? (calculate as a whole)

42.- What types of crimes have you committed? (include those which have not been formalized neither sentenced)

43.- Currently, do you belong to any religion? Yes Which one? No

44.- Do you consume alcohol and/or drugs? Yes Which one(s)? Number Frequency No

45.- Have you been diagnosed with some type of illness in mental health? Yes Which one(s)? No

46.- Have you been in treatment? Yes What kind? No

47.- Do any member of your family commit crimes? Yes Who? No

48.- Have you participated in activities inside the jail? Yes Which one(s)? No

49.- Have you participated in post-penitentiary programs Yes Which one(s)? No

50.- Did you have couple currently? Yes No

51.- Linked to crimes? Yes No What type of crimes he perform?

52.- Did you have children? Yes How many? No

53.- Have you worked previously? Yes No

54.- In what? In what way? (e.g.: contract, informal)

55.- Are you working currently? Yes In what? In what way? No

56.- Are you the main economic support of the household? Yes No Who is?

57.- Do you think you return to commit crimes in the future? Yes No Why?

Questionnaire of Motivation to Change

Read carefully the following statements and indicate your degree of agreement in each of them:

“Looking at myself, with absolute sincerity I consider that the existing risk to come back to fall into my problem, in a scale of 0 to 10 points, is _____, being 0 without risk and 10 a maximum risk”.

Self-efficacy questionnaire

Read carefully each one of the following statements and indicate with which frequency these situations have occurred to you:

Social support questionnaire

Read carefully each one of the following statements and indicate with which frequency these situations have occurred to you:

Received: April 09, 2018; Revised: July 31, 2018; Accepted: February 03, 2019

texto em

texto em