Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versão impressa ISSN 0120-9957versão On-line ISSN 2500-7440

Rev Col Gastroenterol v.27 n.2 Bogotá abr./jun. 2012

Characterization of histopathological findings from colorectal tumors from patients in Tolima

Nancy Yaneth Flórez-Delgado, Bióloga, MSc. (1), Mabel Elena Bohórquez, MD, Esp., PhD. (1), Gilbert Mateus, MD, Esp. (2), Rodrigo Prieto Sánchez, Biólogo, MSc. (1), María Magdalena E. de Polanco, PhD. (1), Luis Guillermo Carvajal-Carmona, PhD. (1,3), Jorge Mario Castro, MD, Esp. (2)

(1) Research Group in Cytogenics, Phylogenetics and Population Evolution at the Faculty Sciences and Health Sciences at the Universidad del Tolima, A.A. N° 546, in Ibagué, Colombia. Correspondence: echeverrydepolanco@hotmail.com

(2) Research Group and Teaching at the Hospital Federico Lleras Acosta in Ibagué, Colombia.

(3) Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford. Phone: +44 (0) 1865 287580, Email:luis@well.ox.ac.uk

Received: 18-04-12 Accepted: 26-05-12

Abstract

In Colombia, colorectal cancer is recognized as a major public health problem. Its general tendency is occur more frequently among both genders. It now ranks among the top five in terms of mortality. Using histopathological diagnoses collected from pathology laboratories in Ibagué, Tolima between January 2000 and December 2007, we conducted a retrospective analysis of 191 patients who had colorectal adenocarcinoma. The most important findings are that the average age of diagnosis was over 60 years, most common tumor locations were in the rectum (34.6%) and in the left colon (283%), and the greatest numbers of tumors were tubulovillous adenoma, or villous adenoma. Most of cases were tubular.

Key words

Colorectal cancer, adenocarcinoma, Tolima, histopathology.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is considered to be a major public health problem due to its incidence and mortality. Today it can be said that it is one of the most frequent types of cancer found in both genders. According to the National Institute of Cancerology (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología) incidence of CRC has increased while projections suggest that in the year 2045 its frequency will match that of gastric carcinoma (1, 2). CRC recurs within some families due to hereditary syndromes (3-7) CRC ranks third among cancers as a cause of death in the U.S.A. and ranks second in the UK. (8) Various studies report prevalences from 3.7% to 14.9% (9) with a general tendency towards increasing (10-12). Data from the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC) from 2002 showed that 5.1% of all the cancer cases attended by physicians in Colombia were found in the colon and the rectum (13, 14).

In spite of technological and scientific breakthroughs, diagnosis based on histopathological symptoms is still one of the most often used tools. Consequently recognition of histopathological alterations in the morphology of the normal colonic epithelium (i.e. aberrant crypt foci (ACF), adenoma, polyps, etc.), dysplastic histology and the presence of the associated gene mutations is very important (15).

Angel Arango and colleagues (10) have published studies of epidemiology data about the different types of digestive tract cancer in Colombia between 1980 and 1998 while the studies of Correa P. (16, 17) highlight the epidemiological importance of gastrointestinal cancer and lesions resulting from it. Although the gastric cancer's correlation with diet is mentioned, no clinicopathologic analysis of these cases has been found.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

This is a descriptive, retrospective analysis which was performed on 191 patients from Tolima who were diagnosed between January 2000 and December 2007. Cases were selected based on histopathological diagnoses, in five medical centers in Ibagué. Two of these patients from Tolima were diagnosed in hospitals in Bogotá: Hospital de San José and Hospital San Rafael.

This study obtained approval from the ethics committee of the Universidad del Tolima and permissions from all participating medical centers. We established that all information obtained is anonymous and confidential. Diagnoses coming from Hospital de San José and Hospital San Rafael in Bogotá were delivered and authorized either by the patients themselves or by their families.

Selection of histopathological reports

All cases chosen were colorectal adenocarcinomas. Both surgical specimens and biopsies were studied. Squamous cell carcinomas of the anal canal were excluded from the study because of its embryological origin and because risk factors and prognoses are different. Cases selected were grouped according to their locations in the colon: right colon, transverse colon, left colon, rectum and unspecified colon. Lesions located in the cecal appendix, cecum, hepatic flexure of the colon, and in the ascending colon were grouped in the right colon. Those located in the transverse colon kept this name while and cases located in the descending colon and the sigmoid colon were grouped in the left colon. Given the importance of establishing which cases affected the rectum, a differentiation according to the data registered in the anatomical pathology report was made between the rectum and the sigmoid rectum. Finally, cases in which histopathological diagnoses did not specify tumor location within the colon were grouped as unspecified colon.

Methods and analysis

Histopathological features reported for the selected tumors were analyzed using basic descriptive and statistical treatment with the percentage method.

RESULTS

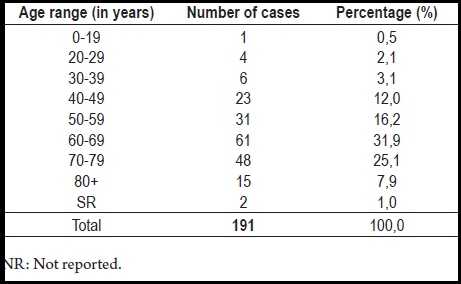

No differences were found in the percentage of colorectal tumors found in each gender; 50.3% (96 cases) were women. The highest percentage of colorectal tumors was found among patients between 60 and 69 years old (31.9%), followed by patients between 70 and 79 years old (25.1%). Finally, it is important to highlight that at the moment of diagnosis, 5.8% of the analyzed patients were between the ages of 0 and 39 years old, a range which shows that heredity can be relevant (Table 1).

Table 1. Ages reported in the histopathological diagnoses for selected tumors.

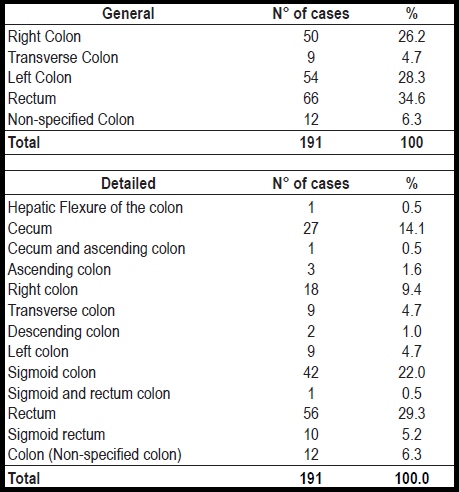

The highest percentage of these tumors were located in the rectum (34. 6%), followed by cases located in the left colon (28.3%) and then in the right colon (26.2%). The lowest percentage was found in the transverse colon (4.7%). Cases in the sigmoid colon (22%) predominated among those in the left colon while cases in the cecum (14.1%) predominated among those in the right colon (Table 2). Only three cases of synchronous tumors were reported in the entire sample.

Table 2. Location of colorectal tumors.

Results from 80 of the cases studied (41.9%) showed tumor origins. The highest frequency identified was for tubular adenomas (25.1%) which were followed by villous tubular adenomas (10.5%), while the lowest frequency of 6.3% was found for villous adenomas. The remaining 58.1% of the cases had unreported origins. Most tumors were well differentiated (50.3%) while 33% of the patients had moderately differentiated tumors. Only 11.5% of the patients had poorly differentiated tumors. For the remaining ten cases (5.2%), no differentiation was reported table 3.

Table 3. Histopathological characteristics of colorectal tumors in relation to their general locations.

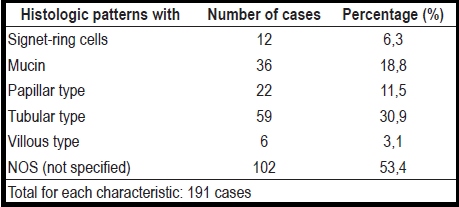

Reports show tubular histological patterns in 30.9% of the cases, mucus in 18.8%, papillary types in 11.5% and signet-ring cells in 6.3% of the cases. The lowest percentage, 3.1%, was for villous type lesions. The remaining 53.4% had no histologic pattern registered (Table 4). Ulcerations were the highest frequency macroscopic characteristics (41.4%) among these colorectal tumors. They were followed by polypoid lesions (17.3%) stenosing annular tumors (2.6%). The remaining 38.7% of these cases had no data reported for macroscopic characteristics. Patients from 70 to 79 years of age had 30% of the cases, the highest frequency, of right colon tumors, while the highest frequencies of both transverse colon tumors (44.4%) and left colon tumors (40.7%) were found among patients between the ages of 60 to 69. This draws our attention to patients who are older than 60 years old who also tend to present most cases of tumors in the rectum. Patients between 60 and 79 years old presented 60.6% of these tumors: 30.3 % for patients between 60 and 69 years old, and 30.3 % for those between 70 and 79 years of age. Among macroscopic characteristics of tumors, ulceration stands out. It occurred in 48% of right colon cases, 44.4% of transverse colon cases, 31.5% of left colon cases, and 45.5% of rectal cases (Table 3).

Table 4. Histologic patterns reported in tumors selected.

DISCUSSION

The importance of knowing the main clinic and pathological characteristics of these tumors stems from the fact that access to genetic and molecular techniques is unusual in the department of Tolima and indeed, throughout Colombia. Diagnosis of this disease through the histopathologic characteristics of the tumor and the medical development of the patient is still the first phase in choosing the kind of treatment and for determining a patient's prognosis.

Gender

No evident differences were found between genders. Apparently this is a disease with equal predispositions for both women and men. This is consistent with reports from other authors (18-27): any person, no matter the gender, can develop a colorectal tumor.

Age

5.8% of our cases were under 40 years old. This is close to what other authors have reported (28, 29). Of theses 11 patients, ten presented moderately differentiated tumors and just one showed a mucinous morphology with signet-ring cells. These patients could be placed within the range of cases that have a family genetic component since manifestation of symptoms of inherited variables of colorectal cancer occurs 10 to 15 years earlier than do sporadic types. In addition, these tumors evolve much more aggressively throughout their development and progression (30).

Most of the patients we analyzed (64.9%) were over 60 years old. This indicates that colorectal tumors are age-related, as has been observed in other studies in which the incidence of colorectal cancer rises as patients' ages increase (18, 23, 26, 29). It has been indicated that more than 90% of the patients diagnosed with CRC are older than 50 (31). In this study even those patients that present mucinous variations (18.8%) or signet-ring cells (6.3%) had an average age of 60. Most of these tumors, as expected, were of the sporadic type (29, 32). However, the average age for the cases diagnosed could be related to the fact that this disease is often asymptomatic during its first stages and to the fact that there is very little available information on this syndrome. Because of this, many patients are diagnosed with CRC when the disease has already evolved into its final stages (28, 33).

Location

Right colon

The percentage of tumors located in the right colon is consistent with reports by other authors (28, 36, 37) It has been found that both sporadic CRC with microsatellite instability (MSI) and nonpolypoid hereditary CRC or, Lynch Syndrome, can be located in the right colon (32, 34, 38, 39).

Transverse colon

The frequency found for transverse colon tumors was 4.7% which is close to the 6.3% reported previously (28) and to the 5% reported by the Hospital Universitario San Vicente de Paul de Medellín (HUSVP), but it is different from the 22% obtained by the HUHMP Hospital Universitario Hernando Moncaleano Perdomo de Neiva (HUHMP) (36) and from the 15% reported by Castellot Martín (37). In this case, it is important to have in mind that it is very difficult to know the exact percentage of tumors located in the transverse colon because these tumors are often grouped with tumors of the right colon due to embryological reasons and the similarity of the surgical methods used in both cases (40).

Left colon

28.3% of the tumors were located in the left colon. This data is consistent (sic) with other authors who have suggested that 68% to 77% of these tumors are located in the left colon (34, 35). Others report 41.4% in the rectum and 14.8% in the sigmoid colon (28). Data from Montenegro, Ramírez, Muñetón, Isaza, & Ramírez (36) that were collected between 1980 and 2000 showed that 28% of cases were located in the descending colon and 42% in the sigmoid colon. At the Hospital Universitario San Vicente de Paúl (HUSVP) in Medellín and the Hospital Universitario Hernando Moncaleano Perdomo (HUHMP) in Neiva, the figures were 44% and 11%, respectively and are consistent with the data we found.

Origin

Most of the CRC cases seem to develop from existing adenomas (41). The risks of adenomas becoming malignant increases as a function of their size (>1cm), amount, histologic type (villous), morphology (sessile) and levels of dysplasia (mild to severe) (41-43). Tubular adenomas are four times more frequent than are villous adenomas. They tend to be smaller and distributed in a more homogeneous manner along the large intestine, while villous adenomas tend to be located in the rectum and have a higher predisposition to becoming malignant (44).

The predominance of tubular adenoma could be due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors that are unique for each of the patients studied. Somatic mutations or germinal variants that favor quick progression of adenomas toward cancer may be present. In some genetic syndromes such as Lynch syndrome, adenomas tend to turn into cancer faster than sporadic adenomas and faster than tumors in patients with mutations of the APC gene. For this reason it is important to urge patients with Lynch syndrome to undergo regular colonoscopies.

According to Avendaño, Fernández, & Deichler (45), tubular adenomas account for 75% of polyps. Of this percentage only 5% are malignant when diagnosed. Tubulovillous adenoma adenomas account for 15% of polyps, and 20% of these cases are malignant. Villous adenomas account for 10% of polyps, and from 35% to 40% of them are malignant. When these results are compared to those obtained for these neoplastic polyps, a decrease in the percentage of tubular adenomas and increases in the percentages of tubulovillous adenomas and villous adenomas can be observed. These are equivalent to 60%, 25% and 15%, respectively for all the registered adenomas.

Villous histology in distal adenomas larger than 1 cm, multiple (distal) adenomas, a family history of colorectal cancer and ages over 65 are factors associated with increased risk for developing distal neoplasia (25).

Degree of Differentiation

Depending on the degree of differentiation, well differentiated and badly differentiated types are similar to the data reported above (28). Moderately differentiated tumors present a percentage of 33% compared to 23.4%. It could be that a percentage of the badly differentiated sporadic and hereditary types might have been associated more with poor differentiation than in conventional carcinomas as it is pointed out in the bibliography (30, 34, 39, 44). In addition, these tumors could have a higher risk of metastasis than differentiated tumors (46).

Histological patterns

When observing the histological patterns of the tumors we analyzed, the tubular type stands out with the highest percentage (30.9%). Mucus was present in 18.8% of these cases, and signet-ring cells were present in 6.3% of the cases. Characteristics such as poor differentiation, mucinous components, signet-ring cells and peri-tumoral lymph node infiltration of the colon such as Crohn's disease are associated with HNPCC patients or with sporadic CRC with MSI (30, 32, 34, 47-50).

Macroscopic characteristics

Annular Stenosing Masses. Only 2.6% of our cases were annular stenosing masses. García, Enriquez & Rodríguez Pérez (23) point out that patients with neoplasias in the distal portion of the colon tend to have annular lesions that affect the entire intestinal lumen and which produce stenosis due to signet-ring cells.

Polypoid tumors. In this study the polypoid tumors accounted for 17.3% of the cases, a higher percentage than the 3% reported elsewhere (28). According to Sack & Rothman (51) their presence doubles the risks of developing a metachronous cancer of the colon. This correlates well with the data reported by Milutín (52) that indicates that polypoid cancers are exophytic tumors which occur most frequently in the colon. It also matches the studies of García Enríquez & Rodríguez Pérez (23) who mention that patients with neoplasias in the cecum and right colon are prone to show exophytic polypoid masses that only rarely cause obstructions.

Macroscopic polypoid characteristics are of great importance in diagnosis and screening of CRC (28, 53) since it is related both to polypoid syndromes and to HNPCC. In HNPCC, polyps occur at the same frequency as in the general population, but they appear at an earlier age and progress more rapidly towards malignancy (2 to 3 years vs. 8 to 10 years in sporadic CRC) (54).

Ulcerated type. This is the most frequent form of colorectal cancer. These tumors have prominent irregular edges which are hard to the touch. They can grow and encircle the whole intestinal circumference and compromise the colonic lumen. Their characteristic radiological image is the "napkin-ring stenosis" or "bitten apple" image. This type is more common in the left colon where it produces symptoms of intestinal obstruction (52). In this study, the percentage of ulcerated macroscopic types was 41.4% which is similar to the reports of Torres-Zavala, Yan-Quiroz, Díaz-Plasencia, & Burgos-Chávez who reported that ulcerated-infiltrating tumors accounted for 37.9% of obstructive CRC and for 30.5% of non obstructive CRC (55). In addition, it can be concluded that most of these cases are located in the left colon.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the patients and their families who voluntarily agreed to take part in the development of this research. To the Comité Central de Investigaciones de la Universidad del Tolima, to the Molecular and Population Genetics Laboratory (MPGL), to Cancer Research UK, Vilma Arias de Devia (cytohisto-technologist) for her support and collaboration in obtaining the required material. To all the participating medical entities (Clínica Manuel Elkin Patarroyo ESE., Hospital Federico Lleras Acosta ESE., Patología-Clínica Tolima, Patología-Centro Médico Javerianos, Patología-Medicadiz) and to the personnel that work in them. To José Luis García Melo (M. Sc) for checking this document.

The researchers of the cytogenetics, phylogeny and population evolution Group of the Universidad del Tolima receive financial support from the CHIBCHA project of the seventh frame program of the European Union.

REFERENCES

1. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC). Anuario Estadístico 2004 "Por el control de cáncer". Bogotá: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2005.

2. Villamizar L, Albis R, Abadía M, Oliveros R, Gamboa O, Alba L, et al. Tamización del cáncer colorrectal en población adulta asintomática: revisión sistemática. Rev Colomb Cancerol 2010; 14(3): 152-68.

3. Álvarez M, Galindo H, Sáez C, Risueño C. El cáncer en la era molecular: conceptos generales y aplicaciones clínicas. Rev Chilena de Cirugía 2002; 54(4): 417-23.

4. Carretero J, Herrerías JM, Delgado P. Oncogenes y cáncer colorrectal. Revis Gastroenterol 2001; 3: 181-98.

5. Helm J, Choi J, Sutphen R, Barthel JS, Albrecht TL, Chirikos TN. Current and evolving strategies for colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Control 2003; 10(3): 193-204.

6. Kruhoffer M, Jensen JL, Laiho P, Dyrskjot L, Salovaara R, Arango D, et al. Gene expression signature for colorectal cancer microsatellite status and HNPCC. Br J Cancer 2005; 92(12): 2240-8.

7. Toledo-González D, Cruz-Bustillo D. La inestabilidad en microsatélites: algunos aspectos de su relación con el cáncer colorrectal hereditario no-polipoide. Rev Cubana Invest Biomed 2005; 24(2): 15.

8. Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United State, 2010: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 2010; 60(2): 90-119.

9. Rivera-Rodríguez D, Cristancho-Cuesta A, González-Jiménez JC. Movilización social para el control del cáncer en Colombia. Bogotá: Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2007.

10. Ángel-Arango LA, Giraldo-Ríos A, Pardo-Turriago CE. Mortalidad por cánceres del aparato digestivo en Colombia entre 1980 y 1998. Análisis de tendencias y comparación regional. Rev Fac Med Univ Nac Colomb 2004; 52(1): 19-37.

11. Ángel-Arango LA, Giraldo-Ríos A, Pardo-Turriago CE. Tasa de mortalidad por cánceres del tubo digestivo según género y grupos de edad en Colombia entre 1980 y 1998. Rev Col Gastroenterol 2008; 23(2): 124-35.

12. Instituto Nacional De Cancerología (INC). Plan Nacional para el Control del Cáncer en Colombia: 2010-2019. Bogotá: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2010.

13. Pardo C, Murillo R, Piñeros M, Castro MA. Casos nuevos de cáncer en el Instituto Nacional De Cancerología, Colombia, 2002. Rev Colomb Cancerol 2003; 7: 4-19.

14. Piñeros M, Ferlay J, Murillo R. Cancer incidence estimates at the national and district levels in Colombia. Salud Publica Mex 2006; 48(6): 455-65.

15. Salovaara R. Molecular pathology of hereditary colon cancer [academic dissertation]. Helsinki: Department of Pathology and Department of Medical Genetics. Haartman Institute and Biomedicum. University of Helsinki; 2004.

16. Correa P. Comments on the epidemiology of large bowel cancer. Cancer Res 1975; 35(11 Pt. 2): 3395-7.

17. Correa P. Epidemiological correlations between diet and cancer frequency. Cancer Research 1981; 41(9 Pt 2): 3685-90.

18. Bannura G, Cumsille MA, Contreras J, Barrera A, Melo C, Soto D, et al. Valor pronóstico de la clasificación TNM 2002 en cáncer de colon y recto. Análisis de 624 pacientes. Rev Chil Cir 2008; 60(3): 202-11.

19. Europacolon España. Se presentan los resultados de la Encuesta sobre el grado de conocimiento del cáncer colorrectal entre la población española, llevada a cabo por europacolon España, la primera asociación de pacientes con esta enfermedad en nuestro país. 2007 [citado; 4]. Disponible en: http:// www.europacolonespana.org /sala-prensa /comunicados/ encuesta.pdf.

20. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC). Anuario estadístico 2005: "Por el control del cáncer". Bogotá: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2007.

21. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC). Anuario estadístico 2006: "Por el control del cáncer". Bogotá: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2007.

22. Solera Albero J, Tárraga López PJ, López Cara MA, Celada Rodríguez A, Carballo Herencia JA, Cerdán Oliver M, et al. Factores hereditarios y cáncer colorrectal. ACAD 2006; XXII (1): 3-8.

23. García Enríquez C, Rodríguez Pérez Y. Estudio anatomopatológico del cáncer de colon y recto en pacientes operados en el Hospital Universitario "Arnaldo Milián Castro". Años 2000-2004. VII Congreso Virtual Hispanoamericano de Anatomía Patológica y I Congreso de Preparaciones Virtuales por Internet. 2005 [citado; 18]. Disponible en: http://www.conganat.org/7congreso/PDF/493.pdf.

24. Piñeros M, Ferlay J, Murillo R. Incidencia estimada y mortalidad por cáncer en Colombia, 1995-1999. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2005.

25. Burt R, Winaver S, Bond J, et al. Preventing colorectal cancer: a clinician's guide. The American Gastroenterological Association; 2004.

26. Corte MG, Gava R, Vizoso F, Rodríguez JC, Fagilde MC, Abdel-Lah O, et al. Características, patrón de manejo y pronóstico del cáncer colorectal. Medifam 2003; 13(3): 151-8.

27. Durán Ramos O, González Ojeda A, Cisneros López FJ, Hermosillo Sandoval JM. Experiencia en el manejo del cáncer colorectal en el Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente. Cirujano General 2000; 22(2): 153-8.

28. Barrero DC, Cortés E, Didí Cruz M, Rodríguez C. Características epidemiológicas y clínicas del cáncer colorectal en pacientes de la ciudad de Ibagué durante el período 2000-2006. Rev Col Gastroenterol 2008; 23(4): 315-26.

29. Galiano de Sánchez MT. Cáncer colorrectal (CCR). Actualización. Bogotá: Asociación Colombiana de Gastroenterología, Endoscopia digestiva, Coloproctología y Hepatología; 2005.

30. Alonso A, Moreno S, Valiente A, Artigas M, Pérez-Juana A, Ramos-Arroyo MA. Mecanismos genéticos en la predisposición hereditaria al cáncer colorrectal. Anales Sis San Navarra 2006; 29(1): 59-76.

31. American Cancer Society (ACS). Colorectal Cancer. 2007 2/22/2007 [cited; 58]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003096-pdf.pdf.

32. Blanco I, Cabrera E, Llort G. Cáncer colorrectal hereditario. Psicooncología 2005; 2(2-3): 213-28.

33. Boletín Información para la Acción (BIA). Registro poblacional de cáncer de Antioquia morbimortalidad por cáncer años 2000-2006. 2007 [citado; 10]. Disponible en: http://www.dssa.gov.co/htm/regca.htm.

34. Achilli L, Hussar V, Penon Busaniche L, Wendeler M, Naves A. La vía "serrada" del adenocarcinoma colorrectal. Rev Méd Rosario 2007; 73: 127-35.

35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DNA testing strategies aimed at preventing hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC); 2005. [citado; 5-11]. Disponible en: http://www.cdc.gov/genomics/gTesting/file/print/FBR/CC_DisorderSetting.pdf.

36. Montenegro Y, Ramírez AT, Muñetón CM, Jiménez LF, Ramírez JL. Comportamiento del cáncer colorectal en pacientes menores de cuarenta años del Hospital Universitario Hernando Moncaleano Perdomo de Neiva (HUHMP) y el Hospital Universitario San Vicente de Paul de Medellín (HUSVP) entre 1980 y 2000. Rev Colomb Cir 2002; 17(1): 10-14.

37. Castellot Martín A. Prevención y cribado del cáncer colorectal esporádico. Disponible en: http://www.scpd.info/documentos/XXV_JORNADAS_SCPD/conf/cancer_colorrectal_esporadico.pdf.

38. Catalán V, Honorato B, García F, Bandrés E, Zabalegui N, Zárate R, et al. Carcinogénesis colónica: proceso de transformación neoplásica. Rev Med Univ Navarra 2003; 47(1): 15-9.

39. Chung DC, Rustgi AK. The hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome: genetics and clinical implications. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138(7): 560-70.

40. Pazos Escudero M [tesis de grado]. Incidencia y supervivencia del cáncer de colon y recto en la provincia de Tarragona (1980-1998), Tarragona: Facultad de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud. Universitat Rovira i Virgili; 2004.

41. Akrami SM. Genetics of hereditary nonpolyposis colorrectal cancer. Arch Iran Med 2006; 9(4): 381-9.

42. Courtier Bonafont R. Análisis de la participación y cumplimiento de la prueba de cribado en un programa de detección precoz de la neoplasia colorectal. Influencia de la forma de contacto con la población diana [tesis de grado]. Barcelona: Facultad de Medicina. Departamento de Cirugía. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona; 2001.

43. Márquez-Velásquez JR, Cáncer de colon. s.f. p. 123-134. Available from: http://www.gastrocol.com/FrontPageLex/libreria/cl0005/pt/CancerColon1208.pdf.

44. Casimiro C. Factores etiopatogénicos en el cáncer colorectal. Aspectos genéticos y clínicos (primera de dos partes). Nutr Hosp 2002; 17(2): 63-71.

45. Avendaño R, Fernández P, Deichler MF. Poliposis de colon. Cuad Cir 2007; 21: 59-64.

46. Ceballos JA. Mucosectomía endoscópica. Rec Colomb Gastroenterol 2003; 18(4): 239-43.

47. Frank SA. Age-specific incidence of inherited versus sporadic cancers: a test of the multistage theory of carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102(4): 1071-5.

48. López Kostner F, Zúñiga A, Wistuba I. Cáncer colorrectal hereditario no poliposo: bases genéticas del tratamiento quirúrgico. Rev Chil Cir 2002; 54(2): 107-13.

49. Maestro ML, Vidaurreta M, Sanz-Casla MT, Rafael S, Veganzones S, Martínez A, et al. Role of the BRAF mutations in the microsatellite instability genetic pathway in sporadic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14(3): 1229-36.

50. Ogino S, Goel A. Molecular classification and correlates in colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn 2008; 10(1): 13-27.

51. Sack J, Rothman JM. Colorectal cancer: natural history and management. Hosp Physician 2000; 36(10): 64-73.

52. Milutín C. Clasificación histológica. Estadificaciones clásicas y actuales del cáncer colorrectal. Revista Médica Universitaria. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas-UNCuyo 2007; 3(2): 13.

53. Charlín-Pato G, Fernández O, García MR, Lamelo F. Cáncer de colon y pólipos. Guías Clínicas 2006; 6(37): 4.

54. Fullerton DA, López F, Rahmer A. Cáncer colorrectal hereditario no poliposo: tratamiento quirúrgico y análisis de genealogías. Rev Med Chile 2004; 132(5): 539-47.

55. Torres-Zavala NM, Yan-Quiroz EF, Díaz-Plasencia JA, Burgos-Chávez OA. Factores pronósticos de sobrevida en cáncer colorrectal resecable obstructivo y no obstructivo. Rev Gastroenterol Perú 2006; 26(4): 363-72.

1. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC). Anuario Estadístico 2004 "Por el control de cáncer". Bogotá: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2005. [ Links ]

2. Villamizar L, Albis R, Abadía M, Oliveros R, Gamboa O, Alba L, et al. Tamización del cáncer colorectal en población adulta asintomática: revisión sistemática. Rev Colomb Cancerol 2010; 14(3): 152-68. [ Links ]

3. Álvarez M, Galindo H, Sáez C, Risueño C. El cáncer en la era molecular: conceptos generales y aplicaciones clínicas. Rev Chilena de Cirugía 2002; 54(4): 417-23. [ Links ]

4. Carretero J, Herrerías JM, Delgado P. Oncogenes y cáncer colorectal. Revis Gastroenterol 2001; 3: 181-98. [ Links ]

5. Helm J, Choi J, Sutphen R, Barthel JS, Albrecht TL, Chirikos TN. Current and evolving strategies for colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Control 2003; 10(3): 193-204. [ Links ]

6. Kruhoffer M, Jensen JL, Laiho P, Dyrskjot L, Salovaara R, Arango D, et al. Gene expression signature for colorectal cancer microsatellite status and HNPCC. Br J Cancer 2005; 92(12): 2240-8. [ Links ]

7. Toledo-González D, Cruz-Bustillo D. La inestabilidad en microsatélites: algunos aspectos de su relación con el cáncer colorectal hereditario no-polipoide. >Rev Cubana Invest Biomed 2005; 24(2): 15. [ Links ]

8. Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United State, 2010: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 2010; 60(2): 90-119. [ Links ]

9. Rivera-Rodríguez D, Cristancho-Cuesta A, González-Jiménez JC. Movilización social para el control del cáncer en Colombia. Bogotá: Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2007. [ Links ]

10. Ángel-Arango LA, Giraldo-Ríos A, Pardo-Turriago CE. Mortalidad por cánceres del aparato digestivo en Colombia entre 1980 y 1998. Análisis de tendencias y comparación regional. Rev Fac Med Univ Nac Colomb 2004; 52(1): 19-37. [ Links ]

11. Ángel-Arango LA, Giraldo-Ríos A, Pardo-Turriago CE. Tasa de mortalidad por cánceres del tubo digestivo según género y grupos de edad en Colombia entre 1980 y 1998. Rev Col Gastroenterol 2008; 23(2): 124-35. [ Links ]

12. Instituto Nacional De Cancerología (INC). Plan Nacional para el Control del Cáncer en Colombia: 2010-2019. Bogotá: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2010. [ Links ]

13. Pardo C, Murillo R, Piñeros M, Castro MA. Casos nuevos de cáncer en el Instituto Nacional De Cancerología, Colombia, 2002. Rev Colomb Cancerol 2003; 7: 4-19. [ Links ]

14. Piñeros M, Ferlay J, Murillo R. Cancer incidence estimates at the national and district levels in Colombia. Salud Publica Mex 2006; 48(6): 455-65. [ Links ]

15. Salovaara R. Molecular pathology of hereditary colon cancer [academic dissertation]. Helsinki: Department of Pathology and Department of Medical Genetics. Haartman Institute and Biomedicum. University of Helsinki; 2004. [ Links ]

16. Correa P. Comments on the epidemiology of large bowel cancer. Cancer Res 1975; 35(11 Pt. 2): 3395-7. [ Links ]

17. Correa P. Epidemiological correlations between diet and cancer frequency. Cancer Research 1981; 41(9 Pt 2): 3685-90. [ Links ]

18. Bannura G, Cumsille MA, Contreras J, Barrera A, Melo C, Soto D, et al. Valor pronóstico de la clasificación TNM 2002 en cáncer de colon y recto. Análisis de 624 pacientes. Rev Chil Cir 2008; 60(3): 202-11. [ Links ]

19. Europacolon España. Se presentan los resultados de la Encuesta sobre el grado de conocimiento del cáncer colorectal entre la población española, llevada a cabo por europacolon España, la primera asociación de pacientes con esta enfermedad en nuestro país. 2007 [citado; 4]. Disponible en: http://www.europacolonespana.org /sala-prensa /comunicados/ encuesta.pdf. [ Links ]

20. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC). Anuario estadístico 2005: "Por el control del cáncer". Bogotá: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2007. [ Links ]

21. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (INC). Anuario estadístico 2006: "Por el control del cáncer". Bogotá: Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2007. [ Links ]

22. Solera Albero J, Tárraga López PJ, López Cara MA, Celada Rodríguez A, Carballo Herencia JA, Cerdán Oliver M, et al. Factores hereditarios y cáncer colorectal. ACAD 2006; XXII (1): 3-8. [ Links ]

23. García Enríquez C, Rodríguez Pérez Y. Estudio anatomopatológico del cáncer de colon y recto en pacientes operados en el Hospital Universitario "Arnaldo Milián Castro". Años 2000-2004. VII Congreso Virtual Hispanoamericano de Anatomía Patológica y I Congreso de Preparaciones Virtuales por Internet. 2005 [citado; 18]. Disponible en: http://www.conganat.org/7congreso/PDF/493.pdf. [ Links ]

24. Piñeros M, Ferlay J, Murillo R. Incidencia estimada y mortalidad por cáncer en Colombia, 1995-1999. Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Ministerio de la Protección Social; 2005. [ Links ]

25. Burt R, Winaver S, Bond J, et al. Preventing colorectal cancer: a clinician's guide. The American Gastroenterological Association; 2004. [ Links ]

26. Corte MG, Gava R, Vizoso F, Rodríguez JC, Fagilde MC, Abdel-Lah O, et al. Características, patrón de manejo y pronóstico del cáncer colorectal. Medifam 2003; 13(3): 151-8. [ Links ]

27. Durán Ramos O, González Ojeda A, Cisneros López FJ, Hermosillo Sandoval JM. Experiencia en el manejo del cáncer colorectal en el Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente. Cirujano General 2000; 22(2): 153-8. [ Links ]

28. Barrero DC, Cortés E, Didí Cruz M, Rodríguez C. Características epidemiológicas y clínicas del cáncer colorectal en pacientes de la ciudad de Ibagué durante el período 2000-2006. Rev Col Gastroenterol 2008; 23(4): 315-26. [ Links ]

29. Galiano de Sánchez MT. Cáncer colorectal (CCR). Actualización. Bogotá: Asociación Colombiana de Gastroenterología, Endoscopia digestiva, Coloproctología y Hepatología; 2005. [ Links ]

30. Alonso A, Moreno S, Valiente A, Artigas M, Pérez-Juana A, Ramos-Arroyo MA. Mecanismos genéticos en la predisposición hereditaria al cáncer colorectal. Anales Sis San Navarra 2006; 29(1): 59-76. [ Links ]

31. American Cancer Society (ACS). Colorectal Cancer. 2007 2/22/2007 [cited; 58]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003096-pdf.pdf. [ Links ]

32. Blanco I, Cabrera E, Llort G. Cáncer colorectal hereditario. Psicooncología 2005; 2(2-3): 213-28. [ Links ]

33. Boletín Información para la Acción (BIA). Registro poblacional de cáncer de Antioquia morbimortalidad por cáncer años 2000-2006. 2007 [citado; 10]. Disponible en: http://www.dssa.gov.co/htm/regca.htm. [ Links ]

34. Achilli L, Hussar V, Penon Busaniche L, Wendeler M, Naves A. La vía "serrada" del adenocarcinoma colorectal. Rev Méd Rosario 2007; 73: 127-35. [ Links ]

35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DNA testing strategies aimed at preventing hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC); 2005. [citado; 5-11]. Disponible en: http://www.cdc.gov/genomics/gTesting/file/print/FBR/CC_DisorderSetting.pdf. [ Links ]

36. Montenegro Y, Ramírez AT, Muñetón CM, Jiménez LF, Ramírez JL. Comportamiento del cáncer colorectal en pacientes menores de cuarenta años del Hospital Universitario Hernando Moncaleano Perdomo de Neiva (HUHMP) y el Hospital Universitario San Vicente de Paul de Medellín (HUSVP) entre 1980 y 2000. Rev Colomb Cir 2002; 17(1): 10-14. [ Links ]

37. Castellot Martín A. Prevención y cribado del cáncer colorectal esporádico. Disponible en: http://www.scpd.info/documentos/XXV_JORNADAS_SCPD/conf/cancer_colorrectal_esporadico.pdf. [ Links ]

38. Catalán V, Honorato B, García F, Bandrés E, Zabalegui N, Zárate R, et al. Carcinogénesis colónica: proceso de transformación neoplásica. Rev Med Univ Navarra 2003; 47(1): 15-9. [ Links ]

39. Chung DC, Rustgi AK. The hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome: genetics and clinical implications. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138(7): 560-70. [ Links ]

40. Pazos Escudero M [tesis de grado]. Incidencia y supervivencia del cáncer de colon y recto en la provincia de Tarragona (1980-1998), Tarragona: Facultad de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud. Universitat Rovira i Virgili; 2004. [ Links ]

41. Akrami SM. Genetics of hereditary nonpolyposis colorrectal cancer. Arch Iran Med 2006; 9(4): 381-9. [ Links ]

42. Courtier Bonafont R. Análisis de la participación y cumplimiento de la prueba de cribado en un programa de detección precoz de la neoplasia colorectal. Influencia de la forma de contacto con la población diana [tesis de grado]. Barcelona: Facultad de Medicina. Departamento de Cirugía. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona; 2001. [ Links ]

43. Márquez-Velásquez JR, Cáncer de colon. s.f. p. 123-134. Available from: http://www.gastrocol.com/FrontPageLex/libreria/cl0005/pt/CancerColon1208.pdf. [ Links ]

44. Casimiro C. Factores etiopatogénicos en el cáncer colorectal. Aspectos genéticos y clínicos (primera de dos partes). Nutr Hosp 2002; 17(2): 63-71. [ Links ]

45. Avendaño R, Fernández P, Deichler MF. Poliposis de colon. Cuad Cir 2007; 21: 59-64. [ Links ]

46. Ceballos JA. Mucosectomía endoscópica. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol 2003; 18(4): 239-43. [ Links ]

47. Frank SA. Age-specific incidence of inherited versus sporadic cancers: a test of the multistage theory of carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102(4): 1071-5. [ Links ]

48. López Kostner F, Zúñiga A, Wistuba I. Cáncer colorectal hereditario no poliposo: bases genéticas del tratamiento quirúrgico. Rev Chil Cir 2002; 54(2): 107-13. [ Links ]

49. Maestro ML, Vidaurreta M, Sanz-Casla MT, Rafael S, Veganzones S, Martínez A, et al. Role of the BRAF mutations in the microsatellite instability genetic pathway in sporadic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14(3): 1229-36. [ Links ]

50. Ogino S, Goel A. Molecular classification and correlates in colorectal cancer. J Mol Diagn 2008; 10(1): 13-27. [ Links ]

51. Sack J, Rothman JM. Colorectal cancer: natural history and management. Hosp Physician 2000; 36(10): 64-73. [ Links ]

52. Milutín C. Clasificación histológica. Estadificaciones clásicas y actuales del cáncer colorectal. Revista Médica Universitaria. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas-UNCuyo 2007; 3(2): 13. [ Links ]

53. Charlín-Pato G, Fernández O, García MR, Lamelo F. Cáncer de colon y pólipos. Guías Clínicas 2006; 6(37): 4. [ Links ]

54. Fullerton DA, López F, Rahmer A. Cáncer colorectal hereditario no poliposo: tratamiento quirúrgico y análisis de genealogías. Rev Med Chile 2004; 132(5): 539-47. [ Links ]

55. Torres-Zavala NM, Yan-Quiroz EF, Díaz-Plasencia JA, Burgos-Chávez OA. Factores pronósticos de sobrevida en cáncer colorectal resecable obstructivo y no obstructivo. Rev Gastroenterol Perú 2006; 26(4): 363-72. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em