Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

versão impressa ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.26 no.2 Medellín jan./jun. 2015

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

LOW FREQUENCY OF ENTEROCOCCUS FAECALIS IN THE ORAL MUCOSA OF SUBJECTS ATTENDING DENTAL CONSULTATION

Carolina Carrero Martínez;1 María Cristina Gonzáliez Gilbert;2 María Alexandra Martínez Lapiolo;3 Fátima Serna Varona;4 Hugo Díez Ortega;5 Adriana Rodríguez Ciodaro6

1 DMD, Endodontics Specialist, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Private

endodontics practice. Bogotá, Colombia.

2 DMD, Universidad de Carabobo, Venezuela. Endodontics Specialist,

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Private endodontics practice,

Valencia, Venezuela.

3 DMD, Universidad de Carabobo, Venezuela. Endodontics Specialist,

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Private endodontics practice,

Barquisimeto, Venezuela.

4 DMD, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Pharmacology Specialist,

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, MSc in Education, Pontificia

Universidad Javeriana. Assistant Professor, School of Dentistry,

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia.

5 Bacteriologist, MSc in Microbiology, PhD in Biological Sciences,

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Professor, School of Sciences,

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia.

6 Bacteriologist, MSc in Microbiology, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana

Bogotá. Associate Professor, Dental Research Center, School of

Dentistry, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia.

SUBMITTED: APRIL 9/2013-ACCEPTED: OCTOBER 14/2014

Carrero C, González MC, Martínez MA, Serna F, Díez H, Rodríguez A. Low frequency of Enterococcus faecalis in the oral mucosa of subjects attending dental consultation. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2015; 26(2): 57-66.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic, unsporulated coccus whose habitat is the

gastrointestinal tract. It can also be found in the hepatobiliary tract, the vagina, and wounds on soft tissues. It has been shown that due to its high

virulence, E. faecalis can penetrate the dentinal tubules, surviving chemical-mechanical instrumentation, colonize them at a depth of 300 Μm and

re-infest the canals even after being obturated, but the source of infection is not clear. The objective of this study was to determine the frequency

and resistance profile of E. faecalis in the oral mucosa of patients attending dental consultation.

METHODS: samples were collected from the gingiva,

gingival sulcus, palate, tongue, and cheeks of 200 adult subjects attending dental consultation. E. faecalis was identified by means of a screening

that included catalase, hemolysis in agar blood, bile esculin, 6.5% NaCl, and PYR, confirming by a Microscan panel (DadeBehring).

RESULTS: E.

faecalis was isolated from the oral microbiota of 10 samples (5%).

CONCLUSIONS: this study found low frequencies of E. faecalis in the oral mucosa

of subjects attending dental consultation.

Key words: Enterococcus faecalis, oral mucosa, oral microflora, endodontics, apical periodontitis.

INTRODUCTION

About 700 bacterial species have been identified in the oral microbiome but Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) is very rarely detected.1-3 However, it has been proven that its presence causes infectious oral diseases such as pulp necrosis, pulp exposure to the oral cavity, and persistent apical periodontitis.4-11

According to Lancefield’s classification, E. faecalis belongs to the streptococci group D. It is a Gram-positive, facultative anaerobic, motionless, unsporulated coccus with many virulent factors such as lipoproteins, cytolysins and proteolytic enzymes like gelatinases and adhesins serine proteases as aggregation substance, Enterococcal Surface Protein (ESP), pheromones, adhesin of collagen from enterococci (ACE) and antigen A, in addition to polysaccharides, both in its cell walls and capsules. Gelatinase is a hydrophobic metalloproteinase with the capability of breaking down insulin, casein, hemoglobin, collagen, and fibrin. Some studies have associated these proteolytic properties with the high occurrence of Enterococcus species in bacteremia, endocarditis, urinary tract infections, and intraradicular infections, where it has been found forming biofilms on hydroxyapatite. However, microorganisms do not always express gelatinase even if they have the gelE gene. ESP is responsible for E. faecalis colonization and persistence during infectious processes; in addition, it promotes the primary interaction between pathogen and host during biofilm formation.12-15

Given the epidemiological warning on the presence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci, various studies have characterized their resistance profile finding out that they also have a natural resistance to penicillin, cephalosporin, clindamycin and fluoroquinolones, and a greater number of strains daily appear with acquired resistance to high concentrations of aminoglycosides, lactams, fluoroquinolones, and erythromycin, to name just a few—important data to take into account when selecting an antibiotic if required for treatment.16

The normal habitat of E. faecalis is the gastrointestinal tract, but it can be temporarily found in the hepatobiliary tract, the vagina, the oral cavity, and soft tissue lesions. Several studies have reported Enterococcus as a colonizer of the oral mucosa; these studies have been conducted in patients and hospital populations, seeking a connection with the nosocomial infection caused by this organism.17-19

E. faecalis has the ability to survive and reproduce in microenvironments that might be toxic to other bacteria, as in the presence of calcium hydroxide, an alkaline antimicrobial agent used as intracanal medication. It has also proven to be able to survive chemical-mechanical instrumentation of root canals, colonizing the dentin tubules to a depth of 300 microns and re-infecting the canals even after obturation. E. faecalis has been identified as a frequent cause of contamination of the root canal system in teeth with endodontic treatment failure. Virulence factors have been associated with the different stages of endodontic infection and periapical inflammation. The frequency of E. faecalis in primary endodontic infections reaches 4%, while persistent periapical lesions often reach 77%, being able to survive as a single microorganism or as a major component in biofilm, causing endodontic treatment failures.2, 4, 20

Considering that E. faecalis is not common in the oral microbiome (but has been found in root canals biofilms where it has been associated with endodontic treatment failure), that the anatomic reservoir site that explains the source of colonization is unknown, and that some of the strains may be resistant to antibiotics, the present study seeks to determine the frequency and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of E. faecalis in the oral mucosa of individuals attending dental consultation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A descriptive observational study was conducted to determine the frequency of E. faecalis in oral mucosa, by selecting a convenience sample of 200 subjects who were being treated at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana School of Dentistry. The following participants were excluded: patients with systemic conditions, smokers, patients who had received antibiotics in the two months prior to sample collection, and subjects with less than four teeth in the mouth. The use of removable prosthesis was taken into account as a possible intervening variable. The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana School of Dentistry.

After obtaining authorization and a signed informed consent from each patient, samples were taken from oral mucosa using two sterile swabs to rub soft tissues in each patient before starting dental treatment. The first swab was used to take samples from the gingiva and buccal sulcus, and the second one to obtain samples from cheeks, palate and tongue. Samples were initially inoculated in prereduced thioglycolate solution, which was used to perform primary isolation in blood agar and selective Enterococci chromocult agar (Merck), incubating at 37°C 5%CO2 for 24 to 48 hours. Red colonies were biochemically identified with catalase tests, hemolysis in blood agar, bile esculin, 6.5% NaCl, and PYR. Presumptive isolated samples were confirmed with the Dade Behring Inc MicroScanSystem, PC34, which identifies phenotype by means of a panel of 25 substrate reagent containers for biochemical reaction and a set of containers of 9 antibiotics.

Analysis of the information: the results are displayed in absolute and relative frequencies of the number of subjects who had E. faecalis in oral mucosa.

RESULTS

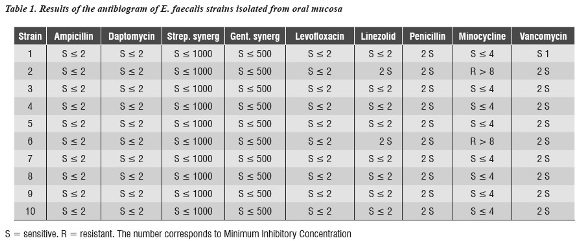

The sample included 200 subjects aged 35 years in average, 135 females and 65 males. E. faecalis was isolated from the oral mucosa of 10 patients (5%) (4 females and 6 males) aged 20 to 65 years (43.4 years in average). Regarding subjects with removable dentures, it was found in 6 of the 10 patients from whom E. faecalis was isolated. Table 1 shows the antibiogram results of the isolated samples that were identified as E. faecalis, whose most important finding was that only two strains were resistant to minocycline. The 8 remaining strains were sensitive to all the antibiotics in the panel.

DISCUSSION

Failure, relapse or reactivation of endodontic lesions after obturation has been completed are conditions dentists face on a regular basis. The presence of E. faecalis has been identified in various oral pathologies, root canals, periodontal pockets, and maladapted obturations, but not in the environment of the oral mucosa, spreading towards sites that favor its colonization.5

Due to its high virulence, E. faecalis produces endodontic therapy failure because once it reaches the root canal, it can adhere to the collagen of dentin, bone, and other tissues, penetrate dentin tubules, resist medications such as calcium hydroxide, survive irrigation with sodium hypochlorite, and form intra- and extra-radicular biofilm, causing persistent periapical lesions.2, 21, 22

For more than twenty years, several authors have reported that the oral cavity can be a reservoir of E. faecalis and is found in 4% of the dental biofilm of hospitalized patients.19, 21-24 The present study included 200 subjects who were taken oral mucosa samples, finding E. faecalis in only 10 patients (5%) —data that for the first time provide an estimate of the frequency of this microorganism in the oral mucosa in the Colombian population—. Sample collection for this research project was done by rubbing soft tissues with a swab in several types of oral mucosa, taking into account the recommendations by Sedgley et al20 in 2005 and Zhu et al23 in 2010, who collected samples by having patients spit in test tubes, which, as the researchers themselves recognize, does not guarantee sufficient gathering of bacteria in the oral cavity.

The present study found out that 60% of the samples that tested positive for E. faecalis came from patients with removable dentures. Despite being an interesting fact, there is not yet enough evidence to associate this finding with the presence of E. faecalis in the mouth, due to its low frequency in this study. In a study in elderly patients—80 years of age in average— in 2005, Kaklamanos et al25 found no statistically significant association between age, presence of Enterococcus and denture use. Another possible explanation is that, because of the physical and chemical characteristics of prosthesis, they are favorable for bacterial colonization.23, 26

A study by Kwang and Abbott27 showed the presence of bacteria on the tooth-restoration contact surface, with acceptable clinical adaptation in all the samples from the control group and the experimental group, by means of scanning electron microscopy in teeth with apical periodontitis and infected canals, with predominance of the morphotype of the cocci group. This confirms once again the hypothesis that the tooth-restoration interface is a possible pathway for bacterial penetration as a source of canal infection and periapical disease, and it also proves that the term "clinically acceptable restoration" is subjective.

Although the presence of E. faecalis in oral mucosa is low, the way this microorganism arrives has not been clarified, as it regularly inhabits the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. It has been suggested that a possible means for it to reach the oral cavity is as a food contaminant and through fermented foods.17, 19, 28

One of the difficulties of treating serious infection produced by E. faecalis is its resistance to several antibiotics, which could suggest that the finding in this study, i. e. only two strains resistant to tetracycline, has no implications for people with highly pathogenic strains. However, when E. faecalis finds an appropriate niche in root canals of difficult antimicrobial access, which favors its growth, the consequences can range from endodontic treatment failure to tooth loss.25, 19

The abovementioned findings suggest that E. faecalis is an occasional and temporary microorganism in the oral cavity, which is able to grow in extreme pH conditions, salts and desiccation. Its mechanism of arrival to the oral cavity has not been clarified, but it can be found in both inpatients and outpatients. It has been established that E. faecalis often causes apical peridontitis and post-endodontic treatment failures. It has been then recommended to complete all the clinical procedures for strict microbiological control, namely removal of any type of removable appliances patients use in the mouth, prior prophylaxis of the tooth to be treated, absolute isolation of the operating area, and entire removal of previous restorations and caries. It is also important to perform endodontic therapy with sterile instruments, abundant and frequent irrigation with 5.25% sodium hypochlorite, activating the substance with ultrasound or other techniques to ensure penetration in the canal’s irregularities, where instruments like files fail to reach and clean sealed canal obturations. Finally, the restorative procedures should avoid exposure of the treated canal to the oral environment, guaranteeing adequate coronal sealing to prevent this microorganism from finding a suitable niche to colonize root canals and lead to endodontic failure.13, 19, 20, 29, 30

The findings of the present study suggest that a low percentage of the population attending dental consultation has E. faecalis in oral mucosa, and that this coccus is sensitive to most of the antibiotics used in this study; therefore, it is important to conduct further research to establish the route of contamination to prevent endodontic treatment failure caused by this microorganism.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare not having conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43(11): 5721-5732. [ Links ]

2. Stuart CH, Schwartz SA, Beeson TJ, Owatz CB. Enterococcus faecalis: its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retratment. J Endod 2006; 32(2): 93-98. [ Links ]

3. He XS, Shi WY. Oral microbiology: past, present and future. Int J Oral Science 2009; 1(2): 47-58. [ Links ]

4.Love RM, Jenkinson HF. Invasion of dentinal tubules by oral bacteria. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2002; 13(2): 171-183. [ Links ]

5. Wang QQ, Zhang CF, Chu CH, Zhu XF. Prevalence of Enterococcus faecalis in saliva and filled root canals of teeth associated with apical periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci 2012; 4(1): 19-23. [ Links ]

6.D'Ercole S, Filippakos A, De Toledo Leonardo R, Pameijer CH, Tripodi D. Enterococcus faecalis leakage of root canal sealers: an ex vivo study. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2012; 26(3): 545-552. [ Links ]

7. Rôsas IN, Siqueira JF Jr. Characterization of microbiota of root canal-treated teeth with posttreatment disease. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50(5): 1721-1724. [ Links ]

8. Dahlen G, Blomqvist S, Almstahl A, Carlén A. Virulence factors and antibiotic susceptibility in enterococci isolated from oral mucosal and deep infections. J Oral Microbiol 2012; 4: doi 10.3402/jom.v4io.10855. [ Links ]

9. Zehnder M, Guggenheim B. The mysterious appearance of enterococci in filled root canals. Int Endod J 2009; 42(4): 277-287. [ Links ]

10. Pardi G, Guilarte C, Cardozo EI, Briceño EN. Detección de Enterococcus faecalis en dientes con fracaso en el tratamiento endodóntico. Acta Odontol Venez 2009; 47(1): 1-11. [ Links ]

11. Siquera JF, Rôsas IN, Ricucci D. Biofilms in endodontic infection. Endodontic Topics 2010; 22(1): 33-49. [ Links ]

12. Zoletti GO, Pereira EM, Schuenck RP, Teixeira LM, Siqueira JF Jr, dos Santos KR. Characterization of virulence factors and clonal diversity of Enterococcus faecalis isolates from treated dental root canals. Res Microbiol 2011; 162(2): 151-158. [ Links ]

13.Fisher K, Phillips C. The ecology, epidemiology and virulence of Enterococcus. Microbiology 2009; 155(6): 1749-1757. [ Links ]

14. Reffuveille F, Leneveu C, Chevalier S, Auffray Y, Rincé A. Lipoproteins of Enterococcus faecalis: bioinformatic identification, expression analysis and relation to virulence. Microbiology 2011; 157: 3001-3013. [ Links ]

15. Guerreiro-Tanomaru JM, de Faria-Júnior NB, Duarte MA, Ordinola-Zapata R, Graeff MS, Tanomaru-Filho M. Comparative analysis of Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation on different substrates. J Endod 2013; 39(3): 346-350. [ Links ]

16. Centikaya Y, Falk P, Mayhall CG. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000; 13(4): 686-707. [ Links ]

17.Kühn I, Iversen A, Burman LG, Olsson-Liljequist B, Franklin A, Finn M et al. Comparison of enterococcal populations in animals, humans, and the environment -a European study. Int J Food Microbiol 2003; 88(2-3): 133-145. [ Links ]

18.Kurrle E, Bhaduri S, Krieger D, Gaus W, Heimpel H, Pflieger H et al. Risk factors for infections of the oropharynx and the respiratory tract in patients with acute leukemia. J Infect Dis 1981; 144(2): 128-136. [ Links ]

19. Smyth CJ, Halpenny MK, Ballagh SJ. Carriage rates of enterococci in the dental plaque of hemodialysis patients in Dublin. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 25(1): 21-33. [ Links ]

20.Sedgley CM, Nagel AC, Shelburne CE, Clewell DB, Appelbe O, Molander A. Quantitative real-time PCR detection of oral Enterococcus faecalis in humans. Arch Oral Biol 2005; 50(6): 575-583. [ Links ]

21.Siqueira JR Jr. Aetiology of root canal treatment failure: why well-treated teeth can fail. Int Endod J 2001; 34(1): 1-10. [ Links ]

22. Duggan JM, Sedgley CM. Biofilm formation of oral and endodontic Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod 2007; 33(7): 815-818. [ Links ]

23. Zhu X, Wang Q, Zhang C, Cheung GS, Shen Y. Prevalence, phenotype, and genotype of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from saliva and root canals in patients with persistent apical periodontitis. J Endod 2010; 36(12): 1950-1955. [ Links ]

24. Chenoweth C, Schaberg D. The epidemiology of enterococci. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1990; 9(2): 80-89. [ Links ]

25. Kaklamanos EG, Charalampidou M, Menexes G, Topitsoglou V, Kalfas S. Transient oral microflora in Greeks attending day centres for the elderly and residents in homes for the elderly. Gerodontology 2005; 22(3): 158-167. [ Links ]

26. Bal BT, Yavuzyilmaz H, Yüzel M. A pilot study to evaluate the adhesion of oral microorganism to temporary soft lining materials. J Oral Sci 2008; 50(1): 1-8. [ Links ]

27. Kwang S, Abbott PV. Bacterial contamination of the fitting surfaces of restorations in teeth with pulp and periapical disease: a scanning electron microscopy study. Aust Dent J 2012; 57: 421-428. [ Links ]

28. Razavi A, Gmür R, Imfeld T, Zehnder M. Recovery of Enterococcus faecalis from cheese in the oral cavity of healthy subjects. Oral Microbiol Immunol 2007; 22(4): 248-251. [ Links ]

29. Luna NA, Santacruz AX, Palacios BD, Mafla AC. Prevalencia de periodontitis apical crónica en dientes tratados endodónticamente en la comunidad académica de la Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia, Pasto, 2008. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2009; 21(1): 42-49. [ Links ]

30. Tobón S, Mesa A. Arismendi J, Domínguez J, Virgen AL. Nuevos enfoques en cirugía perirradicular. Revisión de literatura. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2000; 11(2): 37- 46. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em