INTRODUCTION

For several decades, the use of agrochemicals for control of pests has been the most prevalent method globally. As a result, farmers have resorted to the indiscriminate use of broad-spectrum synthetic pesticides, often unregistered and applied in excessive doses. Consequently, pests have developed resistance to most major pesticide classes. Moreover, the widespread use of these toxic, non-selective pesticides has led to harmful impacts on the health of users, consumers, and non-target organisms, including pollinators and natural predators of insect pests (Cutler & Guedes, 2017; Guedes et al., 2016). Insect resistance to insecticides is defined by IRAC as “an inherited change in the susceptibility of a pest population which is reflected in the repeated failure of an insecticide to achieve the expected level of control when used according to label recommendations for that pest species." This phenomenon is very common due to the misuse of insecticides, mainly because of the selection pressure exerted by the same mode of action of an insecticide on a target pest (IRAC, 2024a). The first documented case of resistance was in 1914; since then, the numbers have been increasing to 16,570 arthropods resistant to at least one class of pesticide have been reported, including mites and insects (Sparks et al., 2020).

In Colombia, the agricultural sector plays a crucial role in the country's economy and food security. The issue of insecticide resistance represents a significant challenge, particularly given the limited research conducted in Colombia. This is due to a lack of interest and awareness regarding its importance in integrated pest management plans. However, there is a greater body of knowledge available on insect vectors of tropical diseases that are medically important. This is because, in 2004, the National Institute of Health of Colombia established the Network for Surveillance of Resistance to Insecticides Used in Public Health. Consequently, there is more extensive documentation of mosquito (Culicidae) resistance to the use of insecticides (Aguirre-Obando et al., 2015; Love et al., 2023; Orjuela et al., 2018).

According to the Arthropod Pesticide Resistance Database (APRD) (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024), there have been 199 documented instances of resistance in Colombia. Of these, 51% pertain to arthropods of medical and veterinary importance. This category includes eight species (101 reports) of mites (Acari) and mosquito vectors of diseases (Diptera: Culicidae). In contrast, the remaining 49% pertains to agricultural importance, distributed among 10 species with 98 reports. This encompasses one species of phytophagous mite and nine species of insects, with Hemiptera and Lepidoptera being particularly prevalent. Some reports suggest that most information on resistance in Colombia relates to Helicoverpa virescens in cotton crops and the whitefly complex in solanaceous and flower crops (Rodríguez & Cardona, 2001).

Currently, there are no research programs in Colombia, and the number of resistant insects and resistance mechanisms remain unknown. Thus, our objective was to conduct the first literature review to obtain a clearer picture of the current situation in our country. It is important to note that insecticide resistance is, and will continue to be, one of the reasons driving the discovery of new molecules for chemical pest control (Lamberth et al., 2013; Maienfisch & Stevenson, 2015; Sparks & Lorsbach, 2017). Nevertheless, the deployment of insecticides represents one of the fundamental pillars of Integrated Pest Management (IPM). It is therefore recommended to establish research lines in the field of agricultural toxicology to evaluate control failures and develop new criteria to modify current management plans while incorporating more sustainable and environmentally friendly alternatives in fumigant applications.

Search strategy

An exhaustive search of bibliographic material in national and international databases was conducted to extract data on the resistance of agricultural pests to insecticides/acaricides in Colombia. No restrictions were placed on the date or type of publication of the information. Articles about resistance and toxicology in the context of medical and veterinary entomology were excluded from the review. A total of 27 documents were obtained, distributed as follows: 16 articles published in national and international journals, nine abstracts and proceedings from national congresses related to agricultural entomology, and two degree theses. Consequently, a total of 17 arthropod species in Colombia have demonstrated resistance to at least one pesticide (Table 1).

Table 1 List of species of arthropods resistant to pesticides in Colombia.

| Taxonomy | Species | No. Reports | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acari: Tetranychidae | Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Boisduval, 1867) | 2a | (Murillo & Mosquera, 1984) |

| Tetranychus bimaculatus Harvey, 1892 | 1b | (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024) | |

| Lepidoptera: Noctuidae | Heliothis virescens Fabricius, 1777 | 5a | (Lozano Cruz, 1967; Rendon et al., 1977; Rendón et al., 1990; Valencia et al., 1993; Wolfenbarger et al., 1973) |

| Heliothis spp. Ochsenheimer, 1816 | 4a | (Alcaraz, 1971; Collins, 1987; Rendon et al., 1978; Rendon & Cardona, 1976) | |

| Heliothis zea Boddie, 1850 | 2b | (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024) | |

| Helicoverpa zea Boddie, 1850 | 1b | (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024) | |

| Spodoptera frugiperda J. E. Smith, 1797 | 2a - 2b | (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024; Ríos-Díez & Saldamando-Benjumea, 2011; Zenner de Polanía, 1996) | |

| Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae | Tecia solanivora (Povolný, 1973) | 2a - 4b | (Bacca et al., 2017; Gutiérrez et al., 2019; Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024) |

| Tuta absoluta (Meyrick, 1917) | 1a | (Haddi et al., 2012) | |

| Lepidoptera: Crambidae | Ostrinia nubilalis * Hübner,1796 | 1b | (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024) |

| Lepidoptera: Erebidae | Alabama argillacea (Hübner, 1823) | 1b | (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024) |

| Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae | Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius, 1889) | 3a - 23b | (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024; Rodríguez et al., 2005, Rodríguez et al., 2012) |

| Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Westwood, 1856) | 2a - 59b | (Buitrago et al., 1994; Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024; Rodríguez & Cardona, 2001) | |

| Coleoptera: Curculionidae (Scolitynae) | Hypothenemus hampei (Ferrari, 1867) | 1a | (Navarro et al., 2010) |

| Coleoptera: Bostrichidae | Rhyzopertha dominica (Fabricius, 1792) | 1a | (Ortega et al., 2021) |

| Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae (Bruchinae) | Zabrotes subfasciatus (Bohemann, 1833) | 1a - 1b | (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024; Tyler & Evans, 1981) |

| Thysanoptera: Thripidae | Thrips palmi Karny, 1925 | 1a | (Rodríguez et al., 2003) |

a. Number of reports in the literature. b. Number of reports in Database APRD (Mota-Sanchez & Wise, 2024). https://www.pesticideresistance.org/. *. According to the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (2024) and a list of quarantine pests that are absent in Colombia, as provided by the Colombian Agricultural Institute, ICA (2024), O. nubilalis has not been reported in Colombia.

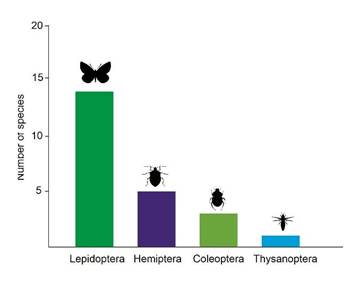

Among insects, the order Lepidoptera is of particular note (60%), with the greatest quantity of resistance information reported in the genus Helicoverpa spp. (formerly known as Heliothis), which is an important defoliator of cotton and corn crops. In the Coleoptera order (20%), certain pests of stored grains and seeds merit particular attention, while in the Hemiptera order (13%), whiteflies -insects associated with virus transmission - warrant further investigation. Finally, the order Thysanoptera reports one species (7%). Additionally, two species of the mite genus Tetranychus, which are known to be phytophagous pests, have been identified as resistant to acaricides in multiple crops (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Number of insects’ species reports per family according to literature records of insecticide-resistant insects in Colombia (n=23).

The veracity of the above-listed pests was corroborated through a review of databases maintained by the Colombian Agricultural Institute (ICA, 2024), the National Open Data Network on Biodiversity (SIB, 2024), and the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization, EPPO Global Database (EPPO, 2024). The objective of this review was to ascertain the presence of these pests within the Colombian context. Our comprehensive analysis revealed that O. nubilalis, a European lepidopteran commonly known as the corn borer, is included in the list of absent quarantine pests that is updated annually by the Colombian Agricultural Institute (ICA, 2024). However, despite its inclusion in the Arthropod Pesticide Resistance Database (APRD) of Mota-Sanchez & Wise (2024), there is a dearth of studies investigating insecticide resistance in this pest within the Colombian context. We attribute this absence to an error in the APRD database.

The use of insecticides is a common practice for controlling insect pests in a variety of crops. After the Second World War and the successful introduction of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), mainly for controlling disease-transmitting insects, it was banned due to its persistent nature and the many contamination problems it caused (Beard, 2006; Jarman & Ballschmiter, 2012; Sánchez-Bayo, 2019). Later, alternative synthetic insecticides emerged, including organophosphates and carbamates (Gupta et al., 2022), which were used as broad-spectrum insecticides due to their ease of acquisition. In Colombia, they were used excessively and with inadequate practices in potato, cotton, corn, and flower crops. Due to the lack of other insecticides with a different mode of action, pests such as the whitefly complex quickly became resistant.

Undoubtedly, the advent and introduction of pyrethroids in the 1980s provided a viable and successful alternative for controlling many pests. In Colombia, they were successfully introduced to control H. virescens and other Lepidoptera in cotton crops. However, due to the lack of alternatives, repeated use and improper dosage in Tolima (Colombia) resulted in control failures and the selection of populations resistant to pyrethroids and organophosphates (Rendon et al., 1977; Rendon et al.,1978; Rendon & Cardona, 1976). Additionally, the corn earworm, S. frugiperda, was reported to exhibit resistance to the same groups in 1985, including carbamates (Table 2) (Zenner de Polanía, 1996). In the 1990s, it was the whitefly complex, consisting of B. tabaci and T. vaporariorum, which are important pests in solanaceous and flower crops. Additionally, the whitefly was found to be associated with virus transmission and demonstrated resistance to the same groups, as well as to organochlorines and neonicotinoids. This finding was based on a synthesis of multiple studies conducted over several years by the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) (Buitrago et al., 1994; Rodríguez et al., 2005).

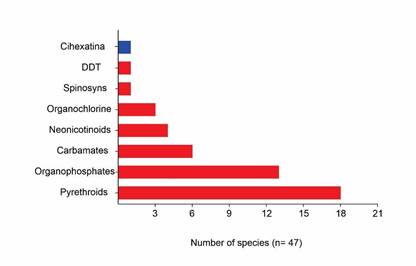

In subsequent years, several studies have reported resistance to the same mode of action across different chemical groups: pyrethroids in T. absoluta, spinosyns, carbamates and organophosphates in T. palmi, and organochlorines in Z. subfasciatus and H. hampei (Table 2). In the last decade, resistance to permethrin, chlorpyrifos, and carbofuran has been reported in T. solanivora and to pyrethroids in R. dominica. Thus, 26 studies report resistance to insecticides with modes of action targeting nerve and muscle systems. Finally, in Colombia, there is only one record of resistance to the respiration-target mode of action of Cihexatina in the mite T. cinnabarinus. A mitochondrial respiration produces ATP, the molecule that energizes all vital cellular processes. The insecticide inhibits the enzyme that synthesizes ATP (IRAC, 2024b).

It is estimated that 98% of the reported cases show resistance at the target site, but these studies are not sufficient to better understand the molecular and genetic basis of resistance mechanisms (Bass & Nauen, 2023; Sajad et al., 2020)

Table 2 Classification of insecticides that are registered for resistance in Colombia.

| Mode of action MoA * | No. | Sub-group | Active Ingredient | Pest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NERVE AND MUSCLE TARGETS Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors Inhibit AChE, causing hyperexcitation. AChE is the enzyme that terminates the action of the excitatory neurotransmitter acetylcholine at nerve synapses. | 1A | Carbamates | Carbofuran | Tecia solanivora |

| Carbosulfan | Thrips palmi | |||

| Methomyl | Bemisia tabaci; Spodoptera frugiperda; Trialeurodes vaporariorum | |||

| 1B | Organophosphates | Chlorpyrifos | Spodoptera frugiperda; Tecia solanivora | |

| Methamidophos | Bemisia tabaci; Trialeurodes vaporariorum | |||

| Monocrotophos | Trialeurodes vaporariorum | |||

| Omethoate | Tetranychus cinnabarinus | |||

| Parathion Methyl | Heliothis virescens | |||

| Pirimiphos methyl | Rhyzopertha dominica | |||

| Profenofos | Trialeurodes vaporariorum | |||

| Triazophos | Heliothis virescens | |||

| Toxametil (Methamidophos) | ||||

| NERVE AND MUSCLE TARGETS GABA-gated chloride channel blockers Block the GABA-activated chloride channel, causing hyperexcitation and convulsions. GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in insects. | 2A | Cyclodiene: organochlorines | Endosulfan | Heliothis virescens |

| NC | Organochlorine | Dieldrin | Hypotenemus hampei | |

| Endrin | Heliothis virescens | |||

| Thiocyclam hydrogen oxalate | Bemisia tabaci | |||

| Dienochlor | Tetranychus cinnabarinus | |||

| Gamma-HCH (Lindano) | Zabrotes subfasciatus | |||

| NERVE AND MUSCLE TARGETS Sodium channel modulators Keep sodium channels open, causing hyperexcitation and, in some cases, nerve block. Sodium channels are involved in the propagation of action potentials along nerve axons. | 3A | Pyrethroids | Bifenthrin | Bemisia tabaci; Rhyzopertha dominica |

| Cypermethrin | Bemisia tabaci; Heliothis virescens; Spodoptera frugiperda; Trialeurodes vaporariorum | |||

| Deltamethrin | Heliothis virescens Trialeurodes vaporariorum; Rhyzopertha dominica | |||

| Fenvalerate | Heliothis virescens | |||

| Lambda-Cyhalothrin | Spodoptera frugiperda | |||

| Permethrin | Tecia solanivora | |||

| 3B | DDT | DDT | Heliothis virescens | |

| NERVE AND MUSCLE TARGETS Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) competitive modulators Bind to the acetylcholine site on nAChRs, causing a range of symptoms from hyper-excitation to lethargy and paralysis. Acetylcholine is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the insect central nervous system. | 4A | Neonicotinoids | Imidacloprid | Bemisia tabaci; Thrips palmi |

| Thiamethoxam | Bemisia tabaci | |||

| NERVE AND MUSCLE TARGETS Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) allosteric modulators - Site I: Allosterically activate nAChRs, causing hyperexcitation of the nervous system. Acetylcholine is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the insect central nervous system. | 5 | Spinosyns | Spinosad | Thrips palmi |

| GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES Mite growth inhibitors affecting CHS1: Inhibit the enzyme that catalyzes the polymerization of chitin. | 10A | Hexythiazox | Cihexatina (Hexythiazox) | Tetranychus cinnabarinus |

*IRAC: Mode of action classification scheme, version 11.2, 08/2024; NC: No current classification

Mechanisms of resistance

As previously stated, resistance is defined as the ability of an insect population to survive and successfully reproduce following exposure to a dose of insecticide that was previously effective in controlling it (Sparks & Nauen, 2015). However, this phenomenon of insecticide resistance is a natural process and is part of the natural process of evolution and adaptation (Costantini, 2019; Madgwick et al., 2023). This adaptive phenomenon involves a strong selection of specific mutations that confer different types of resistance, thus causing failures in IPM (IRAC, 2024a).

However, this phenomenon of insecticide resistance is a natural occurrence and an integral aspect of the evolutionary process (Madgwick et al., 2023). This adaptive phenomenon involves the strong selection of specific mutations that confer different types of resistance, leading to failures in IPM. It is unfortunate that in many cases, resistance is not only present to a chemical compound but in some cases, it also confers cross-resistance to other structurally related agents. This is due to the structural similarity of the compounds and the fact that in many cases, they can share a common target site within the pest, such that they share a common mechanism of action (IRAC, 2024a; Sajad et al., 2020). The hereditary changes present in a pest are associated with genetic mutations that in turn can take different forms and cause different types of resistance, according to IRAC (2024a): a. Target Site Resistance: The occurrence of a mutation at a specific site on the receptor protein results in a reduction in the efficacy of the insecticide (Constant, 1999). b. Metabolic resistance: In this case, insects develop the ability to break down the insecticide through the action of enzymes. For example, they produce higher levels of detoxifying enzymes (such as esterases, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases, or glutathione S-transferases) that can break down or alter the insecticide before it reaches its target site. Additionally, the insect's metabolism adapts to degrade the insecticide more rapidly, reducing its effective concentration (Ranganathan et al., 2022). c. Physical adaptation: In this case, the insect develops a physical adaptation that enables it to evade the insecticide, such as a thicker cuticle, an additional wax layer, or accelerated waste excretion. These adaptations, on their own, do not provide significant protection. However, they are often combined with other mechanisms to enhance effectiveness (Perry et al., 2011). d. Behavioral adaptation: This particular form of resistance is less prevalent, as it entails mutations that have altered the insect's intrinsic behavioral patterns. In order to evade contact with the insecticide, insects may modify their behavior, which may include alterations to their feeding, mating, or shelter-seeking habits, thereby reducing their exposure (Zalucki & Furlong, 2017).

Insects can develop resistance to multiple insecticides, often due to a combination of the above mechanisms or because one mechanism (e.g., detoxification) may confer resistance to insecticides of different chemical classes. This phenomenon is referred to as multiple and cross-resistance. Consequently, the classification of modes of action established by IRAC is intended to assist growers in identifying distinct modes of action, thereby preventing the repetitive utilization of analogous insecticide products and averting the development of resistance (Gnanadhas et al., 2013; Sparks & Nauen, 2015).

Study of resistance in Colombia

The most prevalent form of insecticide resistance is the result of genetic mutations at the site of action, which impair the efficacy of the insecticide. The common examples of this phenomenon include insecticides with a target mode of action in the nervous and muscular systems. A clear example is provided by mutations in the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which confers resistance to organophosphates, or in voltage-dependent sodium channels, which confers resistance to pyrethroids (Chrn et al., 2016; Liu, 2012). In our extensive review, we found that 98% of the literature reports resistance to this mode of action, with multiple species exhibiting resistance to pyrethroids, organophosphates, and carbamates. The remaining two percent can be attributed to the respiration targets' mode of action (Table 2; Figure 2). Of the published papers (n=16), 75% of the research is based on basic toxicity tests using the impregnated vial technique (IRAC, 2011), direct application on immature stages, immersion of the arthropods in different concentrations of the pesticides studied, or in some more specific cases, immersion of the foliage for sucking pests.

Figure 2 Number of species reported as resistant to each chemical group of insecticides/acaricides in Colombia. Blue: growth and development objectives; Red: nerve and muscle targets. (n=47).

Each methodology was adapted to the specific conditions of each laboratory and the experience of the researchers involved. All of the methodologies included pre-tests to determine a mortality rate and subsequent calibration curves to determine the new lethal concentrations (LC) of each product used. Concentration values are calculated using Probit analysis and Abbott's mortality correction. In the majority of studies, comparisons are made between the LC values of a susceptible and a resistant population to determine the resistance ratio (RR) of the species under research to a given compound (Akçay, 2013; Sakuma, 1998). These studies allow the deduction of whether a population is resistant to a specific compound due to the influence of selection pressure. Nevertheless, these studies are unable to ascertain the physiological resistance mechanism that the pest has acquired. It is crucial to study the biological, genetic, and molecular bases of insecticide resistance because it allows for the determination of which physiological process inactivates the insecticide before it reaches its molecular target (Bass & Nauen, 2023; Perry et al., 2015).

A review of the Colombian literature revealed that only four publications (25%) employed methodologies that facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of resistance mechanisms. One study by Valencia et al. (1993) involved enzymatic activity analyses, including esterases, carboxylesterases, the mixed-function oxidase system (MFOs), and cytochrome P-450 activity. This analysis demonstrated an increase in the enzymatic activity of the resistant population of H. virescens to Triazophos. Newer techniques such as high-resolution fusion polymerase chain reaction (PCR) quantification to identify polymorphisms (SNPs) and mutations for rapid identification of Rdl (resistance to dieldrin) alleles in different pest populations were used by Navarro et al. (2010), where they reported the Rdl allele in populations of H. hampei. Similar studies identified pyrethroid resistance mediated by mutation of the para-type sodium channel in various populations of T. absoluta. Haddi et al. (2012) showed that the Rio Negro (Antioquia-Colombia) population exhibited mutations in dr/super-kdr type genes (M918T, T929I and L1014F), which attribute resistance to pyrethroids. Similar results were reported by Bacca et al. (2017), who determined genetic mutations of Kdr genes (L1014F) conferring pyrethroid resistance in T. solanivora of Nariño and Boyacá departments populations.

Challenges and perspectives of resistance in Colombia

Studies on the resistance of agricultural pests to insecticides in Colombia are insufficient due to a lack of knowledge of their importance in IPM programs. In addition to research on the biology of resistant insects that allows us to determine the adaptive costs of the species, it is important to include methodologies related to genetic, biochemical, and molecular analyses to understand the metabolic bases, resistance mediated by the target site, and identify new insecticide targets, in addition to understanding the adaptive costs of resistant species and mitigating the impact currently (Erdogan et al., 2024; Rix et al., 2022; Wang & Wang, 2024). In contrast to surveillance programs for insect vectors of diseases, in Colombia, there are no research and monitoring programs in insecticide toxicology to detect failures in control plans in time and create new strategies that are effective and specific for each species.

General recommendations to avoid and reduce control failures focus on rotation plans for different types of insecticide/acaricide modes of action, using the doses recommended by the manufacturer, respecting the frequency and, if possible, using low-persistence insecticides, taking into account the collateral effect on beneficial insects. In Colombia, some political and legal measures are promoted for specific quarantine pests, regulated by the Colombian Agricultural Institute (ICA). Despite the introduction of new integrated management strategies for specific crops and pests to reduce the impact of resistance, the challenge is difficult. There is a great deal of information on resistance to various insecticides in the carbamate, organophosphate, and pyrethroid groups (Table 2) for H. virescens in cotton and S. frugiperda in maize and rice, but integrated management practices that have rationalized insecticide use have in some cases restored susceptibility, for example, in corn, with the introduction of new molecules such as diflubenzuron and Bt crops. In 2002, transgenic maize and cotton crops were introduced, containing proteins (Cry1Ab or Cry1F) of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), designed to reduce resistant populations and the use of synthetic insecticides in pest control (Blanco et al., 2016; Monnerat et al., 2006). In 2018, the University of Tolima registered the susceptibility of S. frugiperda to lambda-cyhalothrin and methomyl, attributed to the use of BT maize crops (partial findings have been disseminated SOCOLEN congress) (Jaramillo-Barrios et al., 2020; Ríos-Díez & Saldamando-Benjumea, 2011; Rodriguez-Chalarca et al., 2024; Valencia-Cataño et al., 2016; Zenner et al., 2005).

However, there are also many examples of resistance that are challenging, such as T. solanivora in potato crops, where resistant populations have changed their biology as part of their adaptive process. Another example is the whitefly complex, which is highly accentuated in southern Colombia owing to the indiscriminate use of insecticides banned in Colombia but easily accessible due to access to neighboring countries where they are marketed. In this case, the inclusion of new public policies in the agricultural sector is necessary to improve the extension service and attention to farmers, which will make it possible to diagnose pests classified as resistant and create a monitoring network for potentially resistant pests.

The agricultural extension and assistance service in Colombia is primarily managed by personnel from multinational corporations that produce, market, and distribute pesticides. Consequently, there is a dearth of deliberate technical assistance that is genuinely oriented towards integrated pest management plans. Instead, the emphasis is on increasing sales for commissions. A considerable number of products are recommended despite lacking ICA registration for the crop and for the pests and are also used in excess. For this reason, there are control failures in many crops such as avocado, flowers, ornamentals, tomatoes, potatoes, cape gooseberry, and grapes.

Resistance and toxicology studies should go beyond the calculation of new LC50 and toxicity curves; they should aim to determine the metabolic mechanisms used by the pest to detoxify the lethal effect of the insecticide. New molecular tools should be used to analyze in detail the mutations of the genome of each species and to carry out complementary studies on sublethal effects, and adaptive and behavioral costs, to implement specific integrated pest management plans that also include environmentally friendly and sustainable practices.

CONCLUSIONS

The evolution of pest resistance to synthetic insecticides is an evolutionary process driven by selection pressure, which is exacerbated by their inappropriate use. The high reproductive rate of insects, their enzymatic detoxification mechanisms, and selective pressure are all factors that contribute to the proliferation of individuals that possess resistant genes. Addressing this issue necessitates further research to accurately identify resistance mechanisms and formulate species-specific IPM strategies.