What do we know about this issue?

Pediatric pain is a complex entity which is not properly identified or managed. There are few pain prevalence studies in infants and preschool children.

LLANTO is a valuable and easy-to-use tool to asses pain in infants and Spanish-speaking preschool children.

Pain management in early life has long-term physical and emotional consequences.

What new knowledge does this study contribute with?

We used the LLANTO tool to assess pain prevalence in hospitalized infants and preschool children.

Pain prevalence in infants and preschool children was lower than the prevalence reported in studies with the general pediatric population.

Pain assessment in early life is challenging; better assessment tools are required to properly study its prevalence.

INTRODUCTION

Pain is a sensory and emotional experience associated with an actual or potential injury 1; it involves biological, cognitive and social components 2,3. It is a frequent condition among the hospitalized pediatric population 4,5, and usually the assessment and management is not optimal 6-10. It has been said that pain assessment and management in infants and preschool children is challenging due to the cognitive characteristics of this population 11.

Furthermore, the scope of the problem is poorly known due to the lack of local and regional studies 12-14. The few available studies have reliability issues because of the validity of the scales used for pain assessment and follow-up, and because of the size of the population studied 15. Consequently, its prevalence is not accurately known in developed countries 16,17. Furthermore, there is a limited number of studies conducted in low and medium-income countries, and these studies are particularly rare in infants and preschool children, in addition to the fact that there are few validated assessment instruments in languages other than English. This makes the problem even more difficult to approach and its scope is unknown 18-20, particularly in Latin America.

It is also important to establish the prevalence of pain in young children, since they are more vulnerable to pain 18. Experiencing intense pain without proper management early in life has negative consequences with long term effects. Evidence suggests that acute pain in children results in physiological changes, symptomatic experiences that are subsequently more intense and a predisposition to develop chronic pain as adults, as wells as adaptative and emotional issues, with significant physical, social and economic consequences 21-23. The inadequate approach to pain in infants and preschool children evidenced in a number of studies is certainly concerning 24-26.

This paper intends to describe the prevalence of pain in hospitalized infants and preschool children in a third level care center in Colombia; pain was assessed at admission, after 4 and 24 hours and with a validated scale in Spanish, in addition to recording the pharmacological management used.

METHODS

Observational, prospective trial in hospitalized infants and preschool children in the pediatrics department of Hospital Universitario San Rafael de Tunja (HUSRT), from June 2018 to July 2019. This is a third level teaching hospital located in the State of Boyacá, Colombia. The pediatrics department admits all patients from different clinical (pediatrics and pediatric neurology) and surgical specialties (pediatric surgery, orthopedics, maxillofacial surgery, neurosurgery and plastic surgery). The study admission criteria were as follows: hospitalization in pediatrics, hospitalization for at least 24 hours, aged between 5 months and 5 years old. The parent and/or guardian was informed about the child's admission to the trial, and they were allowed to express any concerns and accept the child's participation in the trial signing an informed consent. The exclusion criteria were: refusal of the guardian to let the child participate, hospital stay less than 24 hours, or failure to complete the data collection instrument.

Once the patient was admitted to the pediatric ward, the demographic variables were collected from the medical record of each patient and from a direct interview with the parent or guardian. A last-year medical student previously trained by the principal investigators administered the LLANTO instrument, in the presence of the guardian, in a quiet environment to avoid stressful conditions and reduce potential anxiety biases.

LLANTO was used as an objective instrument to assess pain and avoid measurement biases. This tool has been validated in acute pain in infants and Spanish speaking preschool children, both in Spain 13 and in Colombia 14. LLANTO assesses five pain-associated parameters in children (Crying, oxygen Requirement, Increased vital signs, facial Expression and Sleep) 13. Each segment scores from 0 to 2 and the total sum results in a 0 to 10 score to determine the level of pain. This instrument was used to assess pain at admission, and then after 4 and 24 hours.

Additionally, to identify the management of analgesia, the type of medication prescribed for each patient was recorded. Finally, the subjective perception of the guardian about the analgesic agent administered to the patient was recorded in the final evaluation after 24 hours.

To avoid selection biases, the inclusion criteria were structured and the admission to the trial was randomized. Whilst as already mentioned, the measurement bias was controlled using the LLANTO tool to determine the presence of pain. Lastly, the confounding bias due to anxiety was controlled by assessing in a quite environment in the presence of the guardian and avoiding any stress-associated conditions.

Considering that one of the important limitations of the prevalence studies is the size of the population studied, the sample size estimate was made based on the percentage of infant and preschool population in the region, which is 28.72 % 27. Additionally, the average number of pediatric hospital discharges was considered: 3,000 patients in average. So finally, a target population of 875 children was established, considering an approximate prevalence of pain in previous studies in hospitalized children of 20 % 1,2,17,28. Assuming a 6 % error in the results and a 99 % confidence, the sample was estimated at 221 patients. In view of a potential 12% of missing data, the sample was adjusted to 250 individuals. These patients were randomly admitted to the trial over one year.

Before starting with the data collection, the study was submitted for assessment and approval by the HUSRT medical ethics committee. A unique number was assigned to each patient which was recorded in the survey and then the information was stored in a single Microsoft Excel® database. The analysis of the data was done using Stata® v. 14.2. The quantitative variables were recorded as means with their respective standard deviation (SD) and the qualitative variables were recorded as frequencies and percentages. The inter-group differences (age, gender, service, presence of pain) were studied using T-Student and chi square (X2) for the quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively.

RESULTS

A total of 250 children were assessed. The mean age was 21.4 months (SD +/- 18.07). No significant differences were identified between genders, or in terms of economic status, place of residence, family structure, parents occupation or level of education (Table 1). The children admitted were divided into 2 subgroups: 15.6 % were managed in the surgical service and 84.4 %, in clinical services.

TABLE 1 Sociodemographic characteristics*.

| Age (years, months) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Newborn (one month) | 15 (6) |

| Young infant (1-12 months) | 97 (38.8) |

| Older infant (12-24 months) | 60 (24) |

| Preschool children (3-5 years) | 78 (31.2) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 103 (41.1) |

| Male | 147 (58.8) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Level 1 | 163 (65.2) |

| Level 2 | 68 (27.2) |

| Level3 | 15 (6) |

| Level4 | 4 (1.6) |

| Level of education | |

| No education | 169 (67.6) |

| Kindergarten | 62 (24.8) |

| Elementary school | 19 (7.6) |

| Residential Area | |

| Urban | 158 (63,2) |

| Rural | 92 (36,8) |

| Family circle | |

| Single parent | 17 (6.8) |

| Both parents | 132 (52.8) |

| Extended | 101 (40.4) |

| Occupational status of parents | |

| Unemployed | 10 (2) |

| Employed | 305 (61) |

| Pensioner | 3 (0.6) |

| Student | 8 (1.6) |

| Housewife | 141 (28.2) |

| Other | 33 (6.6) |

| Parents education | |

| None | 3 (0.6) |

| Elementary school | 95 (19) |

| Secondary school | 272 (54.4) |

| Technical career | 49 (9.8) |

| Professional | 58 (11.6) |

| Postgraduate | 7 (1.4) |

| Doesn't know | 16 (3.6) |

| Age of parents | |

| Under 18 years old | 11 (2.2) |

| Between 18-40 years old | 440 (88) |

| Over 40 years old | 42 (8.4) |

| Doesn't know | 7 (1.4) |

| Principal caregiver | |

| Grandparents | 9 (3.6) |

| Mother and father | 239 (95.6) |

| Others | 2(0.8) |

*n = 250.

SOURCE: Authors.

Additionally, at the time of admission, a 12% pain prevalence was evidenced in the total population studied. When dividing into subgroups, 15.6 % (39 patients) were surgical and 84.4 % (211 patients) were clinical (Table 2). In the surgical patients, the pain prevalence at admission was 35.9 % and among the clinical patients was 7.6 %; this difference was significant (p<0.00i). After 4 hours, the pain prevalence was 0.88 % in all patients in the surgical subgroup (2/39). In the final assessment after 24 hours, no pain prevalence was identified using the LLANTO tool (Table 3).

TABLE 2 Distribution by treating specialty.

| Surgical | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Pediatric surgery | 23 (9.2) |

| Plastic surgery | 10 (4) |

| Neurosurgery | 3 (1.2) |

| Orthopedics and traumatology | 2 (0.8) |

| Maxillofacial surgery | 1 (0.4) |

| Total | 39 (15.6) |

| Clinical | |

| Pediatrics | 186 (74.4) |

| Pediatric neurology | 25 (10) |

| Total | 111 (84,4) |

SOURCE: Authors.

TABLE 3 Pain prevalence.

| Subgroup | Admission n (%) | 4 hours n (%) | 24 hours n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | 14 (35.9) | 2(0.8) | 0 |

| Clinical | 16 (7.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 30 (12) | 2(0.8) | 0 |

SOURCE: Authors.

When considering the resulting score using LLANTO in children who presented with pain at admission, the distribution was as follows: 6 points in 0.4 % (1/250), 4 points in 0.8 % (2/250), 3 points in 1.2 % (3/250), 2 points in 4 % (10/250) and 1 point in 5.6 % (14/250). After 4 hours the scores were 2 and 1 point in the 2 patients where pain was identified.

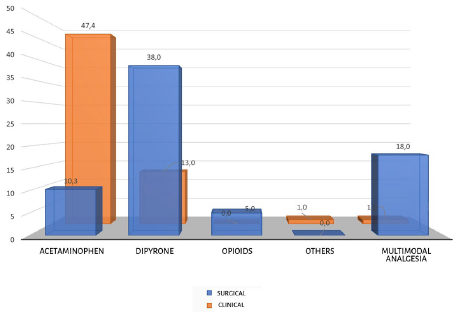

70.8 % (177/250) were prescribed analgesic management at admission, even for patients presenting with pain. The analgesic agents used were acetaminophen in 44.8 % (112/250), dipyrone in 22.8 % (57/250), diclofenac in 1.6 % (4/250) and opioids in 1.2 % (3/250). When assessing by subgroups, in the clinical patients the medications commonly used were acetaminophen 47.4 % and dipyrone 13.6 %. In the surgical group, dipyrone 38.5 %, acetaminophen 10.3 % and opioids 5.1 %. Moreover, multimodal analgesia was used in 4% of the general population, but it was more frequent in the surgical group (Figure 1).

In a raw univariate model an association between the surgical service and the use of dipyrone was identified (OR 6.46 [2.9-14.3] p <0.00i) and an association between the clinical service and the use of acetaminophen (OR 5.38 [2.09-16.31] p <0.001). When analyzing the doses of acetaminophen per weight (10-15 mg/ kg/dose), these were higher in 16.6 % of the surgical patients and in 17.9 % of the clinical patients. This dose was lower in 2.8 % of the clinical group. Finally, the dipyrone dose (10-40 mg/kg/dose) in the surgical group was higher in 40.1 % of the patients. No adverse events were identified with analgesic management during the first 24 hours of hospitalization.

All guardians reported that pain management in children was satisfactory. When asked about the reason for such conclusion, most frequently they argued: "because he/she did not cry", "is calmed" and "has not complained".

DISCUSSION

This paper is new for Spanish-speaking countries among this population and on a large scale. The focus of the authors was to design a study for an objective pain assessment, using a tool with multiple clinical parameters in order to prevent - as much as possible - the risk of bias described with the single parameter scales (such as Wong-Baker) 29 or when using only the subjective perception of the guardian.

The pain prevalence identified using LLANTO is 12 % at the time of hospital admission. This result is similar to that reported by Doca et al. in the subgroup of children in his study, between 29 days and 23 months 28. Moreover, the pain prevalence in this study is lower if compared against studies in the general pediatric population 4,8,9,10,30. Such discrepancy may be due to a different behavior of pain prevalence in the pediatric age subgroups. Hence, several studies indicate that the pain prevalence increases with age, and is higher among adolescents.

Depending on the assessment approach 31-33, pain prevalence in the general pediatric population may exceed 25 % 6,34-37. This has been associated with the fact that many interventions during hospitalization generate pain and anxiety 1,3,6,38,39. In this regard, Kozlowski et al. 35 report that in hospitalized children less than 17 years old, 86 % expressed pain during hospitalization. However, when analyzing by age groups, the study evidences a reduction in pain intensity in those under 5 years old. Unfortunately, this study failed to independently assess pain prevalence by age groups. Reviewing other studies, once again the pain prevalence varies in accordance with the age subgroups, with a lower prevalence in infants and preschool children 40-42.

It may be that these results are due, at least in part, to the sensitivity of the instrument used to assess pain, but this is difficult to proof since there are no other multi-parameter options available in Spanish to contrast the results obtained. It is interesting to note the low scores in most patients with pain, and this could be associated with poor sensitivity of the parameters measured in LLANTO, to identify and quantify pain intensity.

However, when analyzing by subgroups, the pain prevalence in surgical patients was higher and this result is more consistent with the results of most of the pain prevalence studies in pediatrics. The authors of this paper consider that this is due to the fact that LLANTO was originally designed to assess acute postoperative pain 13 and also because surgical-associated trauma results in hypersensitivity. Therefore, using LLANTO to assess both surgical and clinical patients may be controversial. The sensitivity of similar scales has also been questioned; ie., FLAC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability) 31, CHEOPS (Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale), a precursor of LLANTO, since they have only been validated for patients in the perioperative environment 32. It is also possible that the difference in pain prevalence may partly be due to a higher sensibility of LLANTO in surgical patients. However, this study chose LLANTO since it is the only pain assessment scale available for infants and preschool children validated in Spanish 13,14.

Furthermore, when the assessment was conducted, no invasive procedures associated with pain were performed, such as blood tests and punctures, inter alia. The relevance of these procedures has been highlighted in pain prevalence studies that assessed spontaneous patient reports, where two thirds of the children expressed pain during hospitalization 7. Additionally, LLANTO should be administered in a controlled environment and this in itself introduces a potential bias. This could have influenced the results of this study, since children had to be in a quiet environment to be assessed, which involves external control of the elements associated with physical pain and anxiety experienced during hospital care. When dealing with confounding bias, information biases may have been inadvertently generated. These considerations evidence the need to conduct further studies to establish the sensitivity of LLANTO in hospitalized infants and preschool children. It is critical to have effective pain assessment tools, since it is well accepted that pain perception in early life results in permanent changes in physical and emotional development.

In general, it is thought that the pain prevalence identified in this study may be attributed to two reasons: first, a different pain behavior in infants and second, most likely to the poor sensitivity of LLANTO as a tool to assess acute pain in hospitalized infants and preschool children.

Pharmacological treatment to control pain was used in 70.8 % of the patients. Possibly, appropriate pain management was offered from the perspective of medical treatment, since in the final assessment after 24 hours of admission, the prevalence of pain dropped significantly. Monotherapy was more frequently used than multiple medications simultaneously or multimodal analgesia. One of the findings was that in some patients the doses were higher than the doses estimated per body weight. Most patients were prescribed analgesic agents dosed according to schedule. These results are encouraging when compared against other studies that identified inadequate treatment of pediatric patients with pain 1,2,33,35. The analgesia management regimens described in this study are consistent with most of the general recommendations for the management of pediatric pain 43.

It should be highlighted however that the use of dipyrone is controversial 44-46; however, it is an authorized analgesic agent, widely used in pediatric patients in Latin America 47 and in some European countries, including Austria 48 and Spain 49. The safety and efficacy of dipyrone as analgesic agent in infants and preschool children should be further studied.

All guardians were pleased with the analgesic management given to children, and this result is similar to prior studies 50,51, even with a higher pain prevalence 34. The reason for these findings is unclear. It has been suggested that the management expectations may significantly impact the satisfaction outcomes of guardians. Past experiences seem to condition high satisfaction indexes, even in the presence of moderate to severe pain, without being necessarily linked to treatment effectiveness 52. It is then important to consider that pain perception in children should be assessed using additional elements, not just the perception of their guardians or caregivers.

In conclusion, pain prevalence in this paper was lower than the levels described for the general pediatric population. The result may be due to the sensitivity in LLANTO or to a particular pain behavior among infants and preschool children. The subgroup analysis showed that the pain prevalence was higher in surgical patients, but these results should not be generalized. Further studies are required to assess the validity of different pain scales in infants and preschool children, since the assessment tools available for this population are limited. Probably the available scales have sensitivity issues and only LLANTO has been validated in Spanish.

Pain perception in early life involves permanent changes in neurodevelopment and little is known about its prevalence. Therefore, to learn more about the particular factors affecting neurodevelopment, further research is needed on the characteristics and pain assessment instruments.

ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Ethics committee endorsement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital San Rafael de Tunja, at a meeting held on February 21st, 2018, as reported in Minutes number 1.

Protection of humans and animals

The authors declare that no human or animal experiments were conducted for this research. The authors declare that the procedures followed were consistent with the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee and according to the World Medical Federation and the Declaration of Helsinki.

text in

text in