INTRODUCTION

The development of preoperative fasting guidelines at the end of the Twentieth Century lowered the incidence of pulmonary aspiration to just 0.006%, a rate 25 times lower than the rate reported in previous years. 1 This manuscript explores the evolution of medical recommendations and the dogmas associated with preoperative fasting in the history of medicine. The actual fasting times will be addressed, and the behaviors that have influenced the management of surgical patients will be assessed.

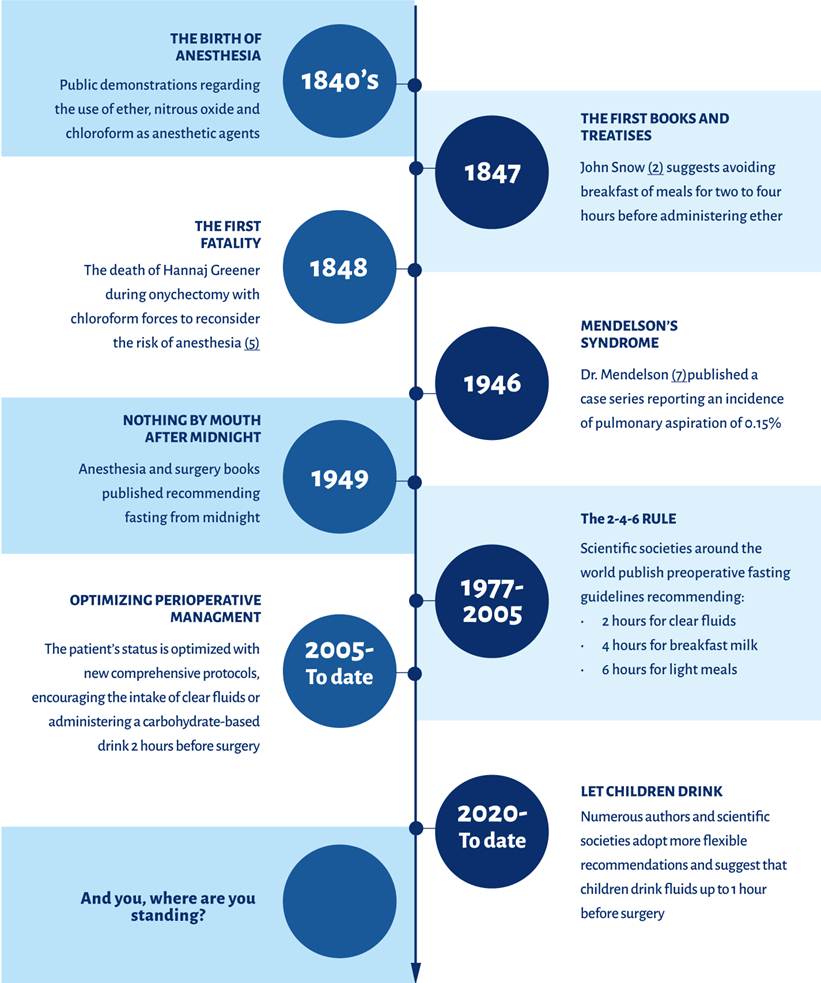

History of the recommendations about preoperative fasting

The history of contemporary anesthesiology dates back to 1840, following the first public displays of the use of ether 2, nitrous oxide 3 and chloroform 3 as anesthetic gases. These agents became popular for minor procedures such as onychectomies, cataract surgery, eye enucleation, exodontia and tumor removal. 2-4 Although these advances marked a milestone in medicine, it did not take long for the first complications to arise.

In January 1848, Hannah Greener underwent an onychectomy procedure under anesthesia with chloroform. only three minutes after the onset of narcosis, the 15-year-old girl had died. The evidence suggested pulmonary aspiration; a full stomach, lung congestion and the administration of drinks during a state of chloroform-induced narcosis. However, the cause of death was presumed as a chloroform overdose and became an unexplained event in the annals of anesthesia. 5

Since this tragedy, the lack of fasting before a procedure under anesthesia would be considered a risk of pulmonary aspiration. This inspired different authors to write in various papers 4 and anesthesia books 6, recommendations for preoperative fasting, with variations between the times and types of food (Table 1). 7 In 1946, one century after the death of Hannah Greener, Doctor Curtis Mendelson published his famous case series on aspiration pneumonitis in obstetric patients, reporting an incidence of pulmonary aspiration of 0.15%. 8 This paper consolidated a medical practice which still prevails: fasting from the night before surgery.

Table 1 Major preoperative fasting recommendations and guidelines (1847-2023).

| Institution/author | Origin/Year | Recommended fasting times | Type of recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Snow J. 2,4,7 | UK 1847 and1858 | Fluids: Not mentioned Solids: 2-4 hours (light meal) 5 hours (full meal) |

Treatise; first anesthesia treatise |

| Gwathmey JT. 6,7 | USA 1914 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 2-3 hours, barley or rice soup |

First anesthesia book in the United States |

| Hunt AM. 7,9 | USA 1949 | Fluids: 2-3 hours Solids: NPO after midnight |

Book |

| Canadian Anesthesiologists' Society 7,10,11 | Canada 1977, 1987 | Fluids: Not mentioned Solids: 5 hours |

Guideline |

| Raeder JC., et al. 12,13 | Norway 1994 | Fluids: 2 hours (oral premeditation up to 1 h) Solids: 6 hours (light meal) Breast milk: 4 hours |

National consensus |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists 14-17 | USA 1999, 2011, 2017, 2023 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours Fats/protein: 8 hours Breast milk: 4 hours |

Guideline |

| Canadian Anesthesiologists' Society, updates 18-20 | Multiple 2000-2019 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours Fats/protein: 8 hours |

Guideline |

| 2020-2023 | Adds fluids: 1 hour (children) | Guideline | |

| European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care 21 | Europe 2011 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours Breast milk: 4 hours |

Guideline |

| ACERTO 22 | Brazil 2005-present | Fluids: 2 hours (carbohydrates) | Protocol |

| ERAS (23) | International Multiple 2005-present | Fluids: Maltodextrin 2-4 hours (administered to the patient) Solids: 6-8 hours |

Protocol |

NPO: Nothing by mouth; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America. Note: all reference to "fluids" means clear liquids, non-dairy, non-particulate, and fatless. For a more comprehensive list, see Complementary material 1.

Source: Authors.

Although prolonged fasting may have been popular in previous years 6,7, the anesthesiology book written by John J. Hunt in 1949, would be the first to suggest prolonged fasting, particularly from midnight, before a procedure under anesthesia. This indication became a tradition passed from generation to generation, despite the new guidelines and findings. 7,24

During the 70's and 80's some concerns were expressed regarding gastric emptying and the deleterious effects of excessive fasting. 7,25 The Canadian Society of Anesthetists was the first scientific authority to publish some guidelines in 1977 10 and then again in 1987 11, recommending five hours of preoperative fasting, with no distinction between fluids and solids.

Years later, in 1993, following the growing evidence supporting the safe intake of clear fluids up to 2 hours before anesthesia, the Norwegian Association of Anesthesiology reached a national consensus suggesting for the first time the indications currently used for preoperative management 12,13: two hours of fasting for clear fluids, four hours for breast milk, and six hours for solids; additionally, allowing for the intake of medications with little water up to one hour before anesthesia in children and adults. Numerous scientific societies around the world published their own similar guidelines and statements over the next decade (Table 1, Figure 1). 14,18,21,26-28

The Fast-Track Era

The preoperative fasting times did not seem to shorten, despite the guidelines on that regard. 24,29 Consequently, in the late 90's and during the 2000 decade, several surgeons from various European institutions organized the ERAS group (Enhanced recovery after surgery) and published their first protocol based on "fast-track" models in 2005 (focusing on procedures with an accelerated recovery and early discharge). 23,30 Likewise, the ACERTO project (Acceleration of total postoperative recovery) in Brazil, adopted measures to improve the postoperative management of patients undergoing abdominal surgery since 2005. 22,31 Among the interventions suggested by both groups, included limiting preoperative fasting to the minimum suggested by the guidelines, and even administering patients a carbohydrate-based drink two to three hours prior to the procedure; such intervention has been maintained in their protocols to this date.

Providing patients carbohydrate-rich drinks before surgery has proven to be beneficial, not just to reduce dehydration, but also discomfort, hunger, thirst, and metabolic effects such insulin resistance. These measures as a whole, together with the rest of the ERAS protocol recommendations, have proven to reduce the hospital length of stay and complications in multiple occasions, improving metabolic and immunologic markers, wellbeing and short and long term outcomes. 32

Additionally, potential benefits have been studied regarding presurgical conditioning based on introducing changes to the diet of patients in a controlled manner for days or weeks, with a view to optimizing or preparing the body prior to a stressor event such as major surgery. 33

The current practice in preoperative fasting management

Notwithstanding the publication of these guidelines, prolonged preoperative fasting is still a frequent practice. Table 2 lists some studies evidencing the fasting times used in various institutions around the world. Times seem to be shorter for institutions in developed countries, particularly in hospitals that implement active interventions to control this issue.

Table 2 Studies reporting preoperative fasting times (without intervention).

| Principal author. Country/year | Sample size | Average length of fasting (hours) | Minimum-Maximum time - Fluids (hours) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solids | Fluids | |||

| Crenshaw 29 USA/2002 | 155 | 14 ± 4 | 12 ± 3 | 3-20 |

| Aguilar-Nascimento 31 Brasil/2006 | 77 | NR | 16 | 8-27 |

| Engelhardt T. 34 UK/2011 | 1,350 (bimodal distribution) | 14.3* | 13.6* | 8.1- 20.8 |

| 6.3* | 5.2* | 0-14.9 | ||

| Cestonaro T. 35 Brasil/2014 | 135 | 16.5* | 15.7* | 2.5-56 (9-21¤) |

| Bilehjani E. 36 Irán/2015 | 250 | 12.5 ± 2.6 | 11.5 ± 2.7 | 3-18 |

| Abebe W. 37 Botsuana/2016 | 260 | 15.9 ± 2.5 | 15.3 ± 2.3 | 12-22 |

| Rangel FL. 38 Colombia/2018 | 292 | 16.2 ± 4.2 | 11.8 ± 4.9 | 2-22 |

| Gómez A. 39 Colombia/2018 | 102 | 15.8 ± 5.8 | 15.8 ± 5.8 | 6.5-43 |

| Isserman R. 40 USA/2019 | 37,081 | NR | 9 ± 5.2 | NR |

| Ramos M. 41 Colombia/2019 | 132 | 14* [12; 16] | 14* [12; 16] | 7-29 |

| Sharkawy A. 42) UK/2020 | 343 | 16.1* [13; 19.4] | 5.8* [3.5; 10.7] | NR |

±: Standard Deviation; *: Median [Q1; Q3]; ¤: Removing extreme values; NR: Not reported; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America.

Source: Authors.

A hospital in the United States managed to ensure that more than 60% of children had an intake of clear fluids between two and four hours prior to surgical procedures, through interventions focused on communication with the family and offering drinks to the children at hospital admission. 40 Similarly, in Brazilian institutions they were able to reduce the preoperative fasting time from 16 to five hours, through educational, awareness and audit activities. 22,31 This illustrates how the lack of institutional policies, poor knowledge, or lack of training with regards to the guidelines may significantly impact perioperative management.

Nowadays, a growing number of authors and scientific societies seek to stimulate the intake of clear fluids and hence reduce fasting times to the minimum established under the guidelines. While the ERAS protocols give their patients a carbohydrate-based drink, the recommendation of encouraging clear fluids intake up to two hours prior to anesthesia has only been reflected in a small number of official publications, including the 2011 European guidelines 21, the Canadian guidelines in all of its versions since 2016 43, and the guidelines of the American Society of Anesthesiology in 2023 17 (Figure 1).

Furthermore, the Canadian Society of Anesthetists adopted the recommendation of one hourfastingfor clear fluids in children since 2020 20, while the International Committee for the Advancement of Procedural Sedation has suggested to abolish fasting for clear fluids in children and adults undergoing procedures under sedation (based on patient's condition and the procedure to be conducted.) 44 However, the ASA clarifies that there is not enough evidence to recommend a one-hour fluids fasting time among the pediatric population, and hence they do not follow such recommendation. 17

The preoperativefastingdogma

There are a number of conditions described in the literature that favor these prolonged preoperative fasting schedules such as the difficulty to ensure individualized diet and indications for each patient undergoing surgery. Likewise, there is a misconception that prolongued fasting is simply uncomfortable rather than unsafe. For this reason, the prescription of "nil per os" (Latin, abbreviated NPO, meaning nothing by mouth) persists among physicians, nurses and administrative staff, from midnight or after 10 p.m. for all patients with a surgical diagnosis, regardless of the time of surgery. 24,29,35,36 Additionally, there is the belief that by ensuring fasting in every surgical patient, it would be easier to move the procedure to an earlier time slot; however, less than 10% of these procedures procedures start before the scheduled time, starting between 30 and 60 minutes. 1

Similarly, fear of procedure cancellation leads both hospital staff and patients to keep a longer fast than necessary, ignoring the detrimental effects of this practice. 24,29 Despite this, extended fasting may not reduce residual volume or decrease stomach acidity. Subjects who fast for three hours may exhibit the same gastric volume as those who have fasted for 25 hours. 45,46 Even people with pathologies such as obesity, diabetes, chronic renal disease and gastroesophageal reflux can maintain an elevated residual gastric volume (up to 3-4 times that of a healthy person), despite the fact that more than eight hours have passed since the last meal. 47

CONCLUSION

This manuscript addresses the historical evolution of preoperative fasting, analyzing how the medical recommendations have changed and how the current practices reflect significant progress since the birth of anesthesiology. The current guidelines use minimal fasting times according to the type of intake: six hours for light meals; two hours for drinks - ideally carbohydrate-based; and in case of children, fasting should only be of four hours for breast milk and one hour for clear fluids. Over the past few years, efforts have been made to reduce prolonged fasting, encouraging intake or even administering something to drink to patients before the surgical procedure.

However, ritualistic behaviors among hospital staff and the lack of patient, family and administrative staff education, favor the persistence of inadequate indications leading to prolonged fasting of surgical patients. Consequently, in order to limit fasting times of surgical patients, an active, institutional, and healthcare associations multidisciplinary effort is needed. The implementation of protocols such as ERAS or ACERTO are economically feasible comprehensive measures that may be adopted at every institution with proven results.

Finally, it should be kept in mind that while the risk of pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents is higher under certain conditions such as obesity and pregnancy, maintaining a more prolonged fasting will probably not alleviate this risk, but on the contrary may increase the sensation of thirst, hunger, irritability, head ache, and insulin resistance, as well as impairment of the physiological stress response to surgical trauma. It is reasonable to conclude that in case of increased risk of pulmonary aspiration, a different or additional approach to fasting might be wiser.

Complementary material 1. Presurgical fasting recommendations and guidelines (1847-2023).

| Institution/author | Origin/year | Recommended fasting time | Type of recommendation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson J. 1,2 | UK 1847 | Not mentioned | Treatise; first anesthesia treatises | |

| Snow J. 1,3,4 | UK 1847 y 1858 | Fluids: Not mentioned Solids: 2-4 hours(light meal) 5 hours (full meal) |

Treatise; first anesthesia treatises | |

| Lister J. 1,5 | UK 1883 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: “no solids in the stomach” |

Book section | |

| Hewitt FW. 1,6 | UK 1905 | Fluids: Not mentioned Solids: 4 hours |

Book | |

| Gwathmey JT. 1,7 | USA 1914 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 2-3 hours, barley or rice soup |

First anesthesia book in the United States | |

| Hunt AM. 1,8 | USA 1949 | Fluids: 2-3 hours Solids: NPO after midnight |

Book | |

| Lee J, Atkinson R. 1,9 | UK 1964 | NPO after midnight or > 6 hours | Book | |

| Canadian Society of Anesthesiologists 1,10,11 | Canada 1977, 1987 | Fluids: Not mentioned Solids: 5 hours |

Guidelines | |

| Kallar S, Everett L. 12 | USA 1993 | Fluids: 2-3 hours Solids: 5 hours |

Review | |

| Stoelting R. 13 | USA 1994 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: NPO on the day of surgery |

Conference | |

| Danish Society of Anesthesia 13 | Denmark 1994 | Fluids: 4 hours Solids: 6 hours |

Bulletin | |

| Raeder JC., et al. 14,15 | Norway 1994 | Fluids: 2 hours (oral premedication up to 1 hours) Solids: 6 hours (light meal) Breast milk: 4 hours |

National consensus | |

| American Society of Anesthesia 16-19 | USA 1999, 2011, 2017, 2023 | Fluids: 2 horas Solids: 6 horas Fats/protein: 8 hours Breast milk: 4 hours |

Guidelines | |

| Canadian Society of Anesthetists, updates 20 | Multiple 2000-2019 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours Fats/protein: 8 hours |

Guidelines | |

| German Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Medicine 21 | Germany 2004 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours Breast milk: 4 hours |

Bulletin | |

| Association of Anesthetists of Great Britain 20,22 | UK 2001, 2005, 2010 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours Breast milk 4 hours |

Guidelines | |

| Scandinavian Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care 23 | Scandinavia 2005 | Fluids: 2 hours (oral premedication up to 1 hour) Solids: 6 hours Breast milk: 4 hours |

Guidelines | |

| Royal College of Nursing 24 | UK 2005 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours |

Guidelines | |

| College of Anesthesiologists, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia 25 | Malaysia 2008 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours |

Guidelines | |

| European Society of Anesthesiology 26 | Europe 2011 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours Breast milk 4 hours |

Guidelines | |

| Royal College of Anesthetists 27 | UK 2012 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours (children) Breast milk: 4 hours |

Compendium of Quality Standards | |

| French society of Anesthesiology 28 | France 2010/ 2012 | Fluids: no more than 2-3 hours Solids: no more than 6 hours |

Guidelines /Experts panel | |

| Rincón D, Escobar B. 29 | Colombia 2015 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 horas Fats/protein: 8 hours |

Clinical Practice Manual | |

| Association of Anesthetists and the British Association of Ambulatory Surgery 30 | UK 2019 | Fluids: 2 hours Solids: 6 hours |

Guidelines | |

| Sociedad Canadiense de Anestesistas, actualizaciones 31 | Canada Multiple 2019 - to date | Fluids: 2 horas/1 hours (children) Solids: 6 hours Fats/protein: 8 hours |

Guidelines | |

| International Committee for the Advancement of Procedural Sedation 32 | Internacional 2020 | Minimal risk* | Fluids: no restriction Solids: 2 hours approx. Breast milk: no restriction |

Consensus |

| Mild risk* | Fluids: no restriction Solids: 4 hours approx. Breast milk: 2 hours approx. |

|||

| Moderate risk* | Fluids: 2 hours approx. Solids: 6 hours approx. Breast milk: 4 hours approx. |

|||

| Colegiado Real de Anestesistas 33 | UK 2020 | Fluids: 2 hours (adults), 1 hour (children) Solids: 6 hours Breast milk: 4 hours |

Compendium of Quality Standards | |

| ACERTO 34 | Brazil 2005-to date | Fluids: 2 hours (carbohydrates) | Protocol | |

| ERAS 35 | International Multiple 2005-to date | Fluids: Maltodextrin 2-4 hours (administered to the patient) Solids: 6-8 hours |

Protocol | |

Approx.: Approximately; NPO: nothing by mouth; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America; *: Risk factors including age, medical conditions and procedure to be conducted; for further information the reader is encouraged to review the reference 32. Note: any mention to "Fluids" refers to clear fluids, non-dairy, no particles and fatless; and solids refers to "light meal", and this definition varies according to the guidelines.

Source: Authors.

REFERENCES

1. Maltby JR. Fasting from midnight - the history behind the dogma. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2006;20(3):363-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpa.2006.02.001

2. Robinson J. A treatise on the inhalation of the vapour of ether. London: Webster; 1847.

3. Snow J. On the inhalation of the vapour of ether in surgical operations. London John Churchill; 1847.

4. Snow J. On chloroform and other anaesthetics: Their action and administration. London John Churchill. 1858;30(5):247-52. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/30.5.247

5. Lister J. On anaesthetics. En: Holmes System of Surgery. 3rd ed. London: Longmans Green and Co.; 1883.

6. Hewitt F. The administration of nitrous oxide and oxygen for dental operations. 2nd ed. London: Claudius Ash, sons & Co; 1905.

7. Gwathmey JT, Baskerville C. Anaesthesia. New York: Appleton; 1914.

8. Hunt A. Anesthesia principles and practice. New York: GP Putnam’s Sons; 1949.

9. Lee J, Atkinson R. A Synopsis of anaesthesia. 5th ed. Oxford: John Wright & Sons Ltd.; 1964.

10. Guidelines to the practice of anaesthesia. The Canadian Anaesthesists’ Society; 1987.

11. Guidelines for the minimal standards of practice of anaesthesia. The Canadian Anaesthesists’ Society; 1977.

12. Kallar SK, Everett LL. Potential risks and preventive measures for pulmonary aspiration. Anesth Analg. 1993;77(1):171-82. https://doi.org/10.1213/00000539-199307000-00034

13. Eriksson LI, Sandin R. Fasting guidelines in different countries. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996;40(8P2):971-4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.1996.tb05614.x

14. Raeder JC, Fasting S, Aanderud L, Soreide E. Preoperative faste og aspirasjonrutiner. NAForum - Tidskr Nor Anestesiol Foren. 1994;7:21-2.

15. Fasting S, SØReide E, Raeder JC. Changing preoperative fasting policies: Impact of a national consensus. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1998;42(10):1188-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.1998.tb05275.x

16. Warner MA, Caplan RA, Epstein BS, Gibbs CP, Keller CE, Leak JA, et al. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: Application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(3):896-905. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-199903000-00034

17. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: Application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(3):495-511. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcbfd9

18. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: Application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(3):376-93. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000001452

19. Joshi GP, Abdelmalak BB, Weigel WA, Harbell MW, Kuo CI, Soriano SG, et al. 2023 American Society of Anesthesiologists practice guidelines for preoperative fasting: Carbohydrate-containing clear liquids with or without protein, chewing gum, and pediatric fasting duration—a modular update of the 2017 American Society of Anesthesio. Anesthesiology. 2023;138(2):132-51. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000004381

20. López Muñoz AC, Busto Aguirreurreta N, Tomás Braulio J. Guías de ayuno preoperatorio: actualización. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2015;62(3):145-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redar.2014.09.006

21. Deutschen Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie und Intensivmedizin (DGAI), Berufsverbandes Deutscher Anästhesisten (BDA). Präoperatives Nüchternheitsgebot bei elektiven Eingriffen. Anästh Intensivmed. 2004;45(12):720. Disponible en: https://www.ai-online.info/images/ai-ausgabe/2004/12-2004/04_12_722.pdf

22. Verma R, Wee M, Hartle A, Alladi V, Rollin AM, Meakin G, et al. Pre-operative assessment and patient preparation. The Role of the Anaesthetist- AAGBI safety guideline 2. Assoc Anaesth Gt Britain Irel. 2010;(January):2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.12146/abstract

23. Soreide E, Eriksson LI, Hirlekar G, Eriksson H, Henneberg SW, Sandin R, et al. Pre-operative fasting guidelines: an update. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49(8):1041-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00781.x

24. Royal College of Nursing. Perioperative fasting in adults and children An RCN guideline for the multidisciplinary team (full version) [Internet]. 2005. [citado: 2021 jul]. Disponible en: https://media.gosh.nhs.uk/documents/RCN_Perioperative_Fasting_Adults_and_Children.pdf

25. College of Anaesthesiologists Academy of Medicine of Malaysia. Guidelines on preoperative fasting. 2008.

26. Smith I, Kranke P, Murat I, Smith A, OʼSullivan G, Sreide E, et al. Perioperative fasting in adults and children. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28(8):556-69. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283495ba1

27. The Royal College of Anaesthetists. Raising the Standard: a compendium of audit recipes for continuous quality improvement in anaesthesia. 3rd ed. Colvin JR, Peden CJ, editors. London; 2012.

28. Chambrier C, Sztark F. French clinical guidelines on perioperative nutrition. Update of the 1994 consensus conference on perioperative artificial nutrition for elective surgery in adults. J Visc Surg. 2012;149(5):e325-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2012.06.006

29. Rincón-Valenzuela DA, Escobar B. Manual de práctica clínica basado en la evidencia: preparación del paciente para el acto quirúrgico y traslado al quirófano. Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rca.2014.10.009

30. Bailey CR, Ahuja M, Bartholomew K, Bew S, Forbes L, Lipp A, et al. Guidelines for day‐case surgery 2019. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(6):778-92. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14639

31. Dobson G, Chau A, Denomme J, Fuda G, Mc-Donnell C, McIntyre I, et al. Guidelines to the practice of anesthesia: Revised Edition 2023. Can J Anesth. 2023;70(1):16-55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02368-0

32. Green SM, Leroy PL, Roback MG, Irwin MG, Andolfatto G, Babl FE, et al. An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on fasting before procedural sedation in adults and children. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(3):374-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14892

33. The Royal College of Anaesthetists. Raising the Standard: a compendium of audit recipes for continuous quality improvement in anaesthesia. Chereshneva M, Johnston C, Colvin JR, Peden CJ, editors. London; 2020.

34. de Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Dock-Nascimento DB, Cadavid Sierra J. El Proyecto ACERTO: un protocolo multimodal barato y eficaz para América Latina. Rev Nutr Clínica y Metab. 2020;3(1):91-9. https://doi.org/10.35454/rncm.v3n1.018

35. Ljungqvist O, Young-Fadok T, Demartines N. The history of enhanced recovery after surgery and the ERAS Society. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2017;27(9):860-2. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2017.0350

text in

text in