What is known about this problem?

The use of non-depolarizing neuromuscular blockers (ND-NMB) can lead to residual neuromuscular blockade (RNMB), which has been associated with respiratory adverse events resulting in prolonged hospital stay.

Its incidence varies widely among different reports, with inconsistencies regarding associated risk factors. Furthermore, there is evidence of poor adherence to intraoperative monitoring recommendations for identifying RNMB

How does this study contribute?

Based on the local and current incidence of RNMB, as well as the description of intraoperative characteristics, we can draw a landscape of the adherence to the new international recommendations for monitoring and managing RNMB. Additionally, this study helps identify potential risk factors associated with RNMB in our region.

INTRODUCTION

The use of non-depolarizing neuromuscular blockers (ND-NMB) improves ventilation conditions, and airway management and favors optimal surgical conditions, constituting a cornerstone of anesthetic management1,2. Residual neuromuscular blockade (RNMB) is an adverse event associated with the use of ND-NMBs, which has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of desaturation in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), pneumonia, the need for intubation, and admission to the intensive care unit 3-5.

The incidence of RNMB has been estimated to range from 0% to 90%, with variability attributed to the different criteria used in its definition, the type of ND-NMB used, and the time between extubation and the measurement of the event 5-16. The possible risk factors associated with the development of RNMB have also not been consistent in the various studies 5-8,17. Considering the inconsistency of risk factors and the poor sensitivity of clinical tests, the diagnosis of RNMB is based on the measurement of the Train of Four ratio (TOFr). However, previous studies have reported low frequency of RNMB monitoring by anesthesia personnel 18,19.

International guidelines on the use of ND-NMB recommend ensuring that TOFr values are greater than or equal to 0.9 prior to extubation in all patients who have received any dose of ND-NMB 2,20,21. We aimed to estimate the incidence, the characteristics of intraoperative monitoring and management, as well as the risk factors associated with RNMB, using a prospective observational study.

METHODS

A cohort study was conducted at a tertiary university hospital in the city of Medellín. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Hospital Alma Máter de Antioquia, Medellín, on October 25, 2022, within the framework of the INS15-2022 project. We followed STROBE recommendations for reporting cohort studies.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Patients were recruited prospectively using convenience sampling. Patients were assessed for eligibility in the hospital's surgical preparation room. Patients over 18 years of age undergoing surgery under general anesthesia in which they received any dose of a ND-NMB were included. The exclusion criteria were patients who were transferred directly to the intensive care unit without remaining in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU); those patients who for some reason did not receive ND-NMB; those for whom TOF measurement was not possible due to monitoring limitations; patients who did not tolerate TOF stimulation and moved their limb during measurement, interfering with precise measurements; or those in whom measurements were not conducted at the specified times. Patients who did not provide a signed informed consent were also excluded.

Measurements

Intraoperative management was at the discretion of the attending anesthesiologist. Anesthesiologists were not informed about patients participation in the study to avoid influencing their usual practice. In this institution, patients are extubated in the operating room. Measurements were conducted in a PACU shared by 14 operating rooms. Within the first 5 minutes of the patient's arrival in the PACU, two TOFr measurements were taken 30 seconds apart, the final result being the average between the two. If the results of these two measurements varied by more than 10%, a third measurement was taken, and the average of the two closest values was considered the final result.

Measurements were performed using a Mindray® NMT module (Nanshan, Shenzhen, China) assigned for the study and calibrated according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The test used four 0.2 ms stimuli, a frequency of 2 Hz, and an intensity between 40 and 55 mA. Electrodes were placed on the ulnar region, 2 to 3 cm apart, and measurements were conducted by the two lead authors and a general physician from the PACU area, after making sure they had performed a minimum of 50 measurements in the past, according to the 2018 consensus on perioperative neuromuscular monitoring 21. We performed non-normalized TOFr to expose patients to fewer stimuli, or to avoid doing it in the operating room, which could create a bias among the institution's anesthesiologists.

If any degree of RNMB was observed in patients, immediate notice was given to the attending anesthesiologist, and pharmacological reversal was suggested. Under no circumstances was this notification omitted. All patients were followed for 72 hours through medical records documented by the treating physicians or until discharge, whichever came first.

The demographic and perioperative characteristics of the patients were obtained from the anesthesia record, verbal information provided by the attending anesthesiologist during handover to the PACU staff, and electronic medical records completed by the treating physicians.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of RNMB in the PACU, defined as a TOFr less than 0.9. Secondary outcomes included describing the perioperative clinical characteristics of patients with RNMB and exploratory identification of potential risk factors associated with RNMB. Additionally, the study aimed to determine the incidence of postoperative intubation, pneumonia, and cardiac arrest within the first 72 hours after discharge from the PACU.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 300 patients was estimated, assuming an incidence of 25% based on the average reported in the literature 3,7,8, with a margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 95%.

Regarding the primary outcome, the frequency was estimated for the entire study group, with absolute frequency presented as the number of patients with the diagnosis over the total number of patients admitted during the study period. Results are presented as percentages with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI).

To describe the clinical and perioperative characteristics, a descriptive analysis of patient characteristic variables was conducted using central tendency and dispersion measurements. Absolute and relative frequencies are presented for categorical variables. Quantitative variables are described with mean and standard deviation values. Normality assumptions were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Median and interquartile range were used as measures of central tendency and dispersion, respectively.

A bivariate analysis was conducted to evaluate potential perioperative risk factors associated with the development of RNMB, and the degree of association is presented in terms of odds ratios (OR). Hypothesis testing was performed using the Fisher's exact test, and p-values are reported. After the bivariate analysis, a multivariate analysis was conducted using binary logistic regression to establish adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for variables identified as significant in the bivariate analysis (p < 0.1). Assumptions of independence of events, monotonicity of the relationship, and absence of collinearity were considered. CI of 95% were calculated for OR values, along with p-values. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The SPSS software version 27 was used for the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

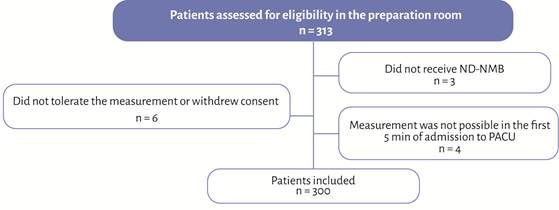

Between November 2022 and February 2024, 300 eligible patients were included in the study (Figure 1). In the PACU, 57 patients were found to have some degree of RNMB, corresponding to an incidence of 19% (95% CI: 14.9% - 23.8%). Among these patients, 48 had a TOF ratio between 0.9 and 0.7 (84.2%), and 9 had a TOF ratio between < 0.7 and 0.4 (15.8%). No patient had a TOF ratio less than 0.4.

ND-NMB: non-depolarizing neuromuscular blockers; PACU: post-anesthesia care unit. Source: Authors.

Figure 1 Flow diagram.

The main demographic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Most patients with residual blockade were female (p = 0.020), with ASA III classification, whereas those without the event were predominantly younger male patients with ASA I and II classifications. The main comorbidities in both groups included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic renal insufficiency.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics.

| Variable | No RNMB (n=243) | RNMB (n=58) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Median (IQR) | 54 (38.5-67) | 63 (44-73) | 0.019* |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 116 (47.7 %) | 37 (64.9 %) | 0.020* |

| Male | 127 (52.3 %) | 20 (35.1 %) | |

| Weight (kg), Median (IQR) | 66 (59-77) | 67 (55-75) | 0.796 |

| Height (m), Median (IQR) | 1.65 (1.57-1.70) | 1.60 (1.56-1.70) | 0.148 |

| ASA Classification | 0.007* | ||

| ASA I | 38 (15.7 %) | 6 (10.9 %) | 0.439 |

| ASA II | 112 (46.1 %) | 16 (28.1 %) | 0.019* |

| ASA III | 89 (36.6 %) | 35 (61.4 %) | 0.001* |

| ASA IV | 4 (1.6 %) | 0 | 1.0 |

| BMI > 35, n (%) | 13 (5.3 %) | 6 (10.5 %) | 0.105 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 92 (37.9 %) | 22 (38.6 %) | 0.918 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 (15.2 %) | 14 (24.6 %) | 0.091 |

| Heart failure | 20 (8.2 %) | 2 (3.5 %) | 0.218 |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 (2.5 %) | 2 (3.5 %) | 0.661 |

| Solid organ cancer | 29 (11.9 %) | 12 (21.1 %) | 0.071 |

| Hematologic cancer | 2 (0.8 %) | 0 | 0.492 |

| Metastatic disease | 5 (2.1 %) | 4 (7.0 %) | 0.048* |

| Chronic lung disease | 12 (4.9 %) | 4 (7.0 %) | 0.529 |

| Chronic renal failure | 21 (8.6 %) | 6 (10.5 %) | 0.655 |

| Hypothyroidism | 17 (7.0 %) | 5 (8.8 %) | 0.643 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome | 3 (1.2 %) | 2 (3.5 %) | 0.227 |

| Polyneuropathy or neuromuscular junction disease | 4 (1.6 %) | 3 (5.3 %) | 0.104 |

| Acute or chronic liver failure | 2 (0.8 %) | 0 | 0.492 |

| Acute kidney injury | 6 (2.5 %) | 5 (8.8 %) | 0.023* |

| Neurodegenerative disease | 3 (1.2 %) | 0 | 0.399 |

| Aminoglycoside administration | 2 (0.8 %) | 0 | 0.492 |

*p-values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

BMI: Body mass index, IQR: Interquartile range; RNMB: residual neuromuscular block.

Source: Authors.

The most common surgical procedure was abdominal surgery. The main ND-NMB used was rocuronium in 92% of cases, with an average dose of 0.55 mg-kg-1 in patients without RNB compared to 0.57 mg-kg-1 in those with RNB, with no statistical differences (P = 0.324). Intraoperative monitoring of RNMB was performed in only 21.3% of cases, and pharmacological reversal measures were not used in 48.7% of cases. The other intraoperative characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Intraoperative management characteristics.

| Variable | No RNMB (n=243) | RNMB (n=57) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Abdominal | 82 (33.7 %) | 31 (54.4 %) | 0.004* |

| Head and neck | 28 (11.5 %) | 5 (8.8 %) | 0.550 |

| Orthopedic | 27 (11.1 %) | 4 (7.0 %) | 0.360 |

| Thoracic | 23 (9.5 %) | 6 (10.5 %) | 0.807 |

| Urological | 21 (8.6 %) | 3 (5.3 %) | 0.397 |

| Neurological | 18 (7.4 %) | 3 (5.3 %) | 0.568 |

| Plastic | 13 (5.3 %) | 1 (1.8 %) | 0.247 |

| Maxillofacial | 12 (4.9 %) | 1 (1.8 %) | 0.289 |

| Vascular | 11 (4.5 %) | 1 (1.8 %) | 0.336 |

| Gynecological | 5 (2.1 %) | 2 (3.5 %) | 0.883 |

| Soft tissue | 3 (1.2 %) | 0 | 0.399 |

| Perioperative use of magnesium sulfate, n (%) | 11 (4.5 %) | 4 (7.0 %) | 0.437 |

| ND-NMB n (%) | |||

| Rocuronium | 226 (93.0 %) | 50 (87.7 %) | 0.186 |

| Cisatracurium | 17 (7.0 %) | 7 (12.3 %) | |

| Rocuronium dose, mg (SD) | 36.4 (13.8) | 38.3 (15.2) | 0.765 |

| Cisatracurium dose, mg (SD) | 8.23 (4.1) | 11.5 (7.3) | 0.005* |

| More than one dose of ND-NMB, n (%) | 46 (18.9 %) | 22 (38.6 %) | <0.001* |

| Intraoperative monitoring of muscle relaxation, n (%) | 56 (23.0 %) | 8 (14.0 %) | 0.135 |

| Neuromuscular reversal agent, n (%) | |||

| None | 112 (46.1 %) | 34 (59.6 %) | 0.065 |

| Neostigmine | 68 (28 %) | 15 (26.3 %) | 0.800 |

| Sugammadex | 63 (25.9 %) | 8 (14.0 %) | 0.057 |

| Neostigmine dose, mg (SD) | 1.82 (0.49) | 1.93 (0.48) | 0.245 |

| Time between administration of the relaxant and extubation less than 120 minutes, n (%) | 118 (48.6 %) | 34 (59.6 %) | 0.132 |

* p-values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

BMI: Body mass index, ND-NMB: non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocker.

Source: Authors.

After adjusting for potential confounders, the exploratory analysis found, among the risk factors for the development of RNMB, that female gender, use of multiple doses of NDNMB, abdominal surgery, and lack of pharmacological reversal were associated with a higher risk of RNMB in the postoperative period (Table 3).

Table 3 Risk factors associated with the development of residual neuromuscular blockade.

| Variable | OR (IC 95 %) | p-value | Adjusted OR (CI 95%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age older than 63 years | 1.82 (1.02-3.26) | 0.043 | 1.47 (0.71-3.07) | 0.295 |

| Female gender | 2.02 (1.11-3.69) | 0.021 | 1.97 (1.02-3.81) | 0.045* |

| ASA classification III | 2.75 (1.52-4.98) | <0.001 | 1.89 (0.86-4.11) | 0.112 |

| Non-use of pharmacological reversal | 4.01 (1.53-10.78) | 0.005 | 2.31 (1.02-5.24) | 0.046* |

| BMI > 35 | 2.08 (0.16-5.74) | 0.156 | 1.58 (0.49-5.14) | 0.445 |

| Acute kidney injury | 3.80 (1.11-12.9) | 0.033 | 2.84 (0.73-10.99) | 0.131 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.81 (0.90-3.64) | 0.095 | 1.44 (0.62-3.30) | 0.387 |

| Solid tumors | 1.97 (0.93-4.14) | 0.075 | 1.47 (0.56-3.91) | 0.434 |

| Metastatic disease | 3.59 (0.93-13.83) | 0.063 | 1.21 (0.24-6.13) | 0.818 |

| Neuromuscular junction disease | 3.31 (0.72-15.26) | 0.123 | 5.12 (0.92-28.4) | 0.062 |

| Abdominal surgery | 2.34 (1.30-4.20) | 0.004 | 2.81 (1.37-5.72) | 0.005* |

| More than one dose of NDNMB intraoperatively | 3.62 (1.73-7.57) | <0.001 | 2.77 (1.48-5.18) | 0.001* |

| No monitoring of neuromuscular relaxation | 1.83 (0.82-4.10) | 0.140 | 1.71 (0.69-4.29) | 0.249 |

| Time between ND-NMB administration and extubation < 120 min | 1.56 (0.87-2.81) | 0.134 | 1.91 (0.95-3.82) | 0.066 |

* p-values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

BMI: Body mass index, ND-NMB: non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocker.

Source: Authors.

Within the first 72 hours, no patients required ventilatory support or orotracheal intubation. There were no reports of respiratory arrest or death. Only one patient in the RNMB group (1.8%) was diagnosed with pneumonia, compared to none in the non-RNMB group.

DISCUSSION

This study found a high number of patients with RNMB, with an estimated incidence of 19% in the PACU. This value is lower tan the findings reported in prospective observational studies such as RECITE and RECITE US, which reported incidences of 44% and 64%, respectively 7,8, and it is higher tan the recently published INSPIRE-2 study, which reported an incidence of only 5% in the PACU 10.

The higher incidence in RECITE and RECITE US can be explained by differences in the study population, as both studies included only patients undergoing abdominal surgery, which has been described as a risk factor for RNMB 16. Consistent with this, we found an association between abdominal surgery and increased risk of RNMB with an OR of 2.81 (95% CI 1.37 - 5.72). This increased risk in abdominal surgery may be attributed to the need for repeated doses of ND-NMB to facilitate optimal surgical conditions. In our analysis, these additional doses were associated with a higher risk of RNMB, with an OR of 2.77 (95% CI 1.48 -5.18), creating the need for greater caution in this type of patients.

In INSPIRE-2, 96% of patients received pharmacological reversal, 92% with sugammadex. In our study, only 51% of patients received pharmacological reversal, predominantly with neostigmine (53%), which may explain the higher incidence we reported compared to INSPIRE-2. We found an association between the absence of pharmacological reversal and the risk of RNMB, with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.31 (95% CI 1.02 - 5.24). However, we did not observe a statistically significant difference between the use of neostigmine or sugammadex and the frequency of RNMB, as described in two previous studies 22,23.

In our population, only 21% of patients had evidence of intraoperative monitoring, a value lower than previously reported in other regions 24,25 and below what is recommended by recent international guidelines and consensus statements 2,20,21. This low frequency of monitoring may be related to the limited availability of monitors in operating rooms and to a lack of awareness among professionals about the RNMB.

Interestingly, we did not find an association between the absence of intraoperative monitoring and the risk of RNMB. However, the proportion of monitored patients was higher in the group without RNMB.

The low dose of ND-NMB used in the patients in this study is striking. One explanation could be that this intraoperative approach aims to avoid cases of RNMB, given the low frequency of monitoring and pharmacological reversal that we observed. Female sex has consistently been identified as a risk factor associated with RNMB 10,17,26,27. Consistent with these findings, our study showed an association of female sex with an increased risk of RNMB, with an OR of 1.97 (95% CI 1.02 - 3.81). This has been attributed to differences in the proportion of adipose tissue and lean mass in women, which could explain the shorter onset and longer duration of effect observed with rocuronium 28,29.

Although previous studies have described risk factors associated with RNMB such as age, time less than 120 minutes since the last dose ND-NMBD, renal disease, oncologic disease, hypothyroidism, or hepatic failure, this study did not find a statistically significant association 6,16,17,30. This inconsistency in risk factors highlights the need for universal monitoring.

This study provides current data on RNMB in a tertiary university hospital in Colombia. These data differ from previous estimates that reported the use of vecuronium and pancuronium, which are associated with a higher risk of RNMB and are currently not commonly used in anesthesia practice in our setting 11,12. Despite this change in the ND-NMB administered and international recommendations for monitoring and management in all patients who have received one of these drugs, the findings of this research should encourage efforts to improve intraoperative monitoring and management practices for RNMB, as a marker of good anesthesia practice.

Strengths

To the authors' knowledge, the prospective analysis of a large number of patients in this study represents the largest cohort in our country. We successfully identified risk factors associated with residual neuromuscular blockade RNMB that were statistically significant after adjusting for confounding factors. These risk factors may suggest which patient populations or surgical models require heightened vigilance. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the anesthesiologists managing intraoperative care were unaware of the patients' participation in the study, thereby reducing the Hawthorne effect and potential biases.

Limitations

This study employed convenience sampling rather than randomization. Data collection took place at a tertiary university hospital, which may differ from the monitoring and pharmacological reversal practices of other hospitals and limit its external validation. The time between extubation and arrival at the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) was not quantified, potentially underestimating the incidence of the event. Additionally, non-normalized TOFr was measured, which may underestimate the incidence of the event. Furthermore, the study design did not allow for the evaluation of potential complications associated with RNMB, as immediate pharmacological reversal after diagnosis of RNMB was recommended in all cases due to ethical considerations.

Future research could focus on identifying the factors that determine the low frequency of intraoperative monitoring of RNMB by anesthesiologists in our region. Additionally, studies on the cost-effectiveness of pharmacological reversal agents and universal TOFr monitoring are needed, as well as studies that include pediatric populations.

CONCLUSION

RNMB in our setting is a common condition, characterized by a low frequency of intraoperative monitoring. Female gender, abdominal surgery, absence of pharmacological reversal, and repeated doses of

ND-NMB were identified as risk factors associated with RNMB, suggesting scenarios requiring heightened vigilance.

ETHICAL DISCLOSURES

Ethics committee approval

This study was approved by the institutional Research Ethics Committee of Hospital Alma Máter de Antioquia, in a meeting held on October 25, 2022, within the framework of the INS15-2022 project.

Protection of human and animal subjects

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study. The authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

text in

text in