Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Ensayos sobre POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA

Print version ISSN 0120-4483

Ens. polit. econ. vol.30 no.spe67 Bogotá June 2012

El papel de las entidades financieras canadienses en el desarrollo de los mercados financieros en Colombia, 1896–1939*

O papel das entidades financeiras canadenses no desenvolvimento dos mercados financeiros na Colômbia, 1896–1939*

Stefano Tijerina

* The author is at the University of Maine, History Department and School of Economics.

I would like to thank my friend and colleague John Greenman for his editorial suggestions and feedback.

The author is at the University of Maine, History Department and School of Economics.

E–mail: stefano.tijerina@umit.maine.edu.

Document received: 27 October 2011; final version accepted: 19 January 2012.

Canadian financial institutions played an important role in the development of financial markets within Colombia's urban centers. Specifically, insurance companies such as Manufacturers Life Insurance Company and Life Assurance Company of Canada were crucial in the expansion of the insurance business across the Caribbean coast, while Royal Bank of Canada contributed to the development of personal banking operations throughout the nation. This paper looks at the experience of Canadian financial companies in Colombia from the late 1800s to the beginning of World War II. It highlights the competitive nature of international financial business and the role of business leaders, policy, and governments in efforts to secure market shares in emerging nations such as Colombia. This historical research also contributes to a better understanding of the bilateral relations between Colombia and Canada, and the ways in which capitalism expanded across the western hemisphere.

JEL classification: E44, F59, F23, G21, G22, L25, N21, N22, N26, N41, N42, N46, O16.

Keywords: Canadian–Colombian Relations, foreign investment, economic development, international financial markets, capitalism, western hemisphere.

Entidades financieras canadienses desempeñaron un papel importante en el desarrollo de los mercados financieros de las principales ciudades colombianas. Aseguradoras tales como Manufacturers Life Insurance Company y Life Assurance Company of Canada tuvieron un gran impacto en el desarrollo del negocio de seguros en la costa Atlántica, mientras que Royal Bank of Canada contribuyó al desarrollo de la banca personal. Este artículo se centra en las experiencias de entidades financieras canadienses en Colombia desde finales del siglo XIX hasta el comienzo de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Resalta la naturaleza competitiva del negocio financiero internacional y el papel que cumplieron los líderes empresariales, las políticas públicas y los gobiernos en su lucha por el posicionamiento en los mercados emergentes de países como Colombia. Esta investigación histórica también contribuye a un mejor entendimiento de las relaciones bilaterales entre Colombia y Canadá y la forma como el capitalismo se extendió en el hemisferio occidental.

Clasificación JEL: E44, F59, F23, G21, G22, L25, N21, N22, N26, N41, N42, N46, O16.

Palabras clave: relaciones entre Colombia y Canadá, inversión extranjera, desarrollo económico, mercados financieros internacionales, capitalismo, hemisferio occidental.

Entidades financeiras canadenses desempenharam um papel importante no desenvolvimento dos mercados financeiros das principais cidades Colombianas. Asseguradoras tais como Manufacturers Life Insurance Company e Life Assurance Company of Canada tiveram um grande impacto no desenvolvimento do negócio de seguros no litoral Atlântico, enquanto que Royal Bank of Canada contribuiu ao desenvolvimento da banca pessoal. Este artigo se centraliza nas experiências de entidades financeiras canadenses a Colômbia desde o final do século XIX até o começo da Segunda Guerra Mundial. Destaca a competitividade entre entidades financeiras internacionais; e o papel que cumprido pelos líderes financeiros, as políticas públicas e os governos em sua luta pelo posicionamento nos mercados emergentes de países como a Colômbia. Esta pesquisa histórica também contribui para um melhor entendimento das relações bilaterais entre a Colômbia e o Canadá e a forma como o capitalismo se espalhou no hemisfério ocidental.

Classificação JEL: E44, F59, F23, G21, G22, L25, N21, N22, N26, N41, N42, N46, O16.

Palavras chave: relações entre a Colômbia e o Canadá, investimento estrangeiro, desenvolvimento econômico, mercados financeiros internacionais, capitalismo, hemisfério ocidental.

I. Introduction

Canadian financial institutions such as Life Assurance Company of Canada, Manufacturers Life Insurance Company, and Royal Bank of Canada began to offer their services in Colombia between the late 1890s and the early 1900s.1 Canadian multinationals were also interested in the Colombian market because it remained, for the most part, untapped. They initially chose Panama City, Cartagena, and Barranquilla as potential markets because these cities were Colombia's international trading centers at the time. Some British and American financial firms had established operations during the second half of the 1800s, but these operations did not compare to their presence in other Latin American nations such as Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, or even Cuba. The Caribbean and Latin American markets represented a solution to Canadian financial institution's limited domestic market, which did not allow their businesses to grow at the pace of American or European markets. Insurance companies were attracted by the potential of the Caribbean, and included Colombia's Caribbean urban centers as part of their target market. Upon their arrival in Colombia in the late 1890s, Manufacturers Life Insurance Company and Life Assurance Company found a commencing market controlled by locally–owned businesses such as the Compañía Colombiana de Seguros.2 The Royal Bank of Canada found stronger competition on their arrival in 1920, but were able to make their presence felt due to their close relationship with Canadian subsidiary Imperial Oil, which by that time carried out operations in Barrancabermeja on behalf of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. Henceforth, Royal Bank was forced to compete against other financial entities, including the Bank of London, Banco de Bogotá, Banco Alemán Antioqueño, Anglo South American Bank Limited of London, and the French and Italian Bank.3 In both cases, the Colombian market represented a solution to the domestic demographic constraints and limited investment capital of Canadian financial institutions.4

Contrary to the experience of Canadian subsidiaries operating in Colombia during the early 1900s (e.g. Pato Gold Dredging and Imperial Oil), Canadian financial entities were independent and experienced greater decision–making flexibility than their foreign–owned counterparts. The Canadian financial institutions that arrived in Colombia were fully–owned by Canadian capital, and enjoyed the benefits of Canadian policies and government support. This allowed Canadian banking and insurance initiatives in Colombia to be independent from the burdens of British or American control, but did not mean that these institutions were immune to international dependency on larger industrial markets. The Canadian Bank was dependent on the New York Stock Exchange while insurance companies were dependent on the London Stock Exchange. The experiences of both banking and insurance in Colombia revealed the limitations of Canadian multinationals and their dependency on leading international trading institutions.5

Canadian financial entities responded to the international market's demand for financial services in the early twentieth century by branching out into emerging markets across the Caribbean and Latin America. One of these markets was Colombia's Caribbean coast, which by the late 1800s had moved away from the conservative isolationist ideology and the anti–liberal views that characterized Colombia's Andean elites. Coastal urban centers such as Panama, Cartagena, and Barranquilla had moved toward more progressive economic development policies and had implemented liberal policies introduced by foreigners and local merchants that had established contacts with the outside world. Local policy makers and business leaders were instrumental in setting up chambers of commerce, banks, and insurance companies, as well as in establishing favorable business conditions tailored to attract foreign investment and capital. Port city elites who relied on foreign capital for the sustainability of local and regional economies increasingly demanded the implementation of laissez–faire policies that would benefit business and improve the export–driven infrastructure.6 It was under this climate of free–market thinking that Manufacturers Life Insurance Company first arrived in 1896, followed by Sun Life Assurance Company a few years later.

The financial institutions that ventured overseas profited from Canada's deregulated financial system. Lax fiscal and investment policies not only turned Canada into a hub for foreign–owned subsidiaries, but it allowed Canadian financial investors to operate in the international market under more favorable conditions. The federal government willingly supported Canadian financial investors abroad by providing them the flexibility to develop and implement new and sophisticated financial products that allowed them to effectively compete in the international market. While British and American banks were restrained from expanding overseas by their own legislation, the Canadian government was "instrumental in creating a protected market, in which banks could develop competitive strengths," providing a "cornerstone for international growth strategies."7 It was under these favorable conditions that Canadian financial institutions ventured into the Colombian market.

II. Insurance

Toronto–based Manufacturers Life Insurance began to sell policies in Colombia in the late 1890s, followed by the Montreal–based Sun Life Assurance in 1905.8 Both insurance companies centered their business in Cartagena and Barranquilla, taking advantage of the dynamic economy of these two port cities.9 Elites from this region had a more outward view and a "marked readiness to accept new ideas." This included political opposition to policy makers from the interior and their uneasiness toward trade and commerce.10 The United Fruit Company had established operations in Ciénaga in 1899 and used Cartagena's shipping and Barranquilla's business facilities, while British and American mining companies used the main coastal ports for the shipment of gold. Foreign merchants managed their import businesses from cities such as Barranquilla, thereby making it a potential center for life insurance business.

In 1901 the head office of Manufacturers Life Insurance Company issued a press release stating the company was in the process of absorbing the Canadian insurance companies Temperance and General Life Insurance. This was done in order to become a stronger competitor in the international market, demonstrating its intentions to aggressively tap international markets.11 Although it was not openly stated, Manufacturers was branching out to foreign markets in order to bring the company up to par with other Canadian and foreign competitors. The Canadian domestic market was limited, and in order to grow Manufacturers had to underwrite policies outside the country. The company explained that Canadian insurance laws were an advantage, enabling "the Company to get foreign business at less cost than its competitors."12 Buyouts, or what the company called "concentration and amalgamation of financial and other interests," were their objective overseas; the company explained that this was the way in which financial entities competed in the global market.13 Canadian insurance companies willing to expand overseas benefited from pro–business government policies. For instance, a policy allowed the government to set aside a reserve to ensure that policyholders were paid. In essence, the federal government issued a three million dollar reserve "for the protection of policyholders."14 Thanks to policy and potential buyout opportunities, the company was ready to "make a special push for business in the West Indies and Spanish America."15

Commonwealth Caribbean markets were the first ones to be targeted by Manufacturers Life Insurance Company. By 1896, the company had established a branch office in Kingston, Jamaica under the management of Ivanhoe Gadpaille, while South American operations were assigned to William E. Young.16 The Colombian market was initially tapped by Young, who tailored its business to the needs of educated elites that understood the benefits of the financial product. He also sought high–level executives from Canada, Europe, and the United States who resided in Colombia and were interested in protecting their family assets from the dangers of the rugged, wild, and untamed tropical region. Manufacturers, like all other foreign financial institutions operating throughout the Americas, understood that business success in places like Colombia could only be achieved if regional elites were targeted. The masses (the popular class) did not represent a profitable market as they did back home.

Upon its arrival, the Canadian company found it challenging to compete against several local and foreign–owned insurance companies, particularly because these companies had physical offices in Colombia and did not rely on the regional representative model for business expansion. The competitors' long–standing acquaintance with coastal elites also gave them an edge over Manufacturers. Nevertheless, the government–backed product gave them an advantage over their competitors. Canadian insurance companies also benefited from anti–American sentiment that spread across Colombia after the 1903 incidents that led to Panama's independence, as well as the declining influence of Britain within the region.

Manufacturers' operations in Colombia were overshadowed by the more aggressive presence of Sun Life Assurance Company. The beginning of operations in the Colombian Caribbean in 1905 were established through the company's Western Department, which included eleven other Latin American nations and a regional office that tailored to the needs of the Northern and Central British West Indies.17

Sun Life capitalized on the anti–American sentiment and the lack of American presence in the Colombian insurance market.18 The British had a stronger presence at the time, but financial regulations in the United Kingdom made them less competitive in the area of life insurance. Sun Life also benefited from 1906 state legislation in the United States that limited the amount of new business "which New York–based life insurance companies could write," forcing American companies such as Equitable Life Assurance Society and New York Life Insurance Company to abandon their Caribbean and South American operations.19

Sun Life entered the Colombian Caribbean market offering an "unconditional policy," a product that trumped the efforts of any other competitor in the market.20 In essence, the product made life insurance products accessible to any individual without restrictions of any kind, including the selectivity of risk.21 By the time it entered the Latin American market, Sun Life "had an individuality and a character which distinguished it from all rivals; in respect to the terms of the contracts it offered it was indeed in a class of itself."22

Cartagena and Barranquilla were, for the most part, untapped markets; they represented "a virgin field for life insurance."23 Nevertheless, these were unfamiliar territories for Canadian businessmen. The mystery and dangers that stereotypically characterized the tropics at the time forced Sun Life executives to tweak insurance policies to fit the demographics and mortality rates of the particular regions. Although preserving the "unconditional policy," the company established premium tables for the tropical region based on available mortality statistics and other contingencies.24 All tropical business, including Colombia's, was considered a special class in and of itself.25

The company viewed Colombia as a Caribbean nation, and identified Barranquilla's "cosmopolitan bourgeoisie" as an ideal Caribbean market.26 As indicated by the company, Colombia's Atlantic Coast represented a region of prospective high–volume, low–cost business in a "new and almost non–competitive field."27

The Caribbean was a more accessible market than the Canadian market. The Dominion's vast territory was difficult to cover, the population was small, individual wealth was limited, and competition from foreign and Canadian companies made the market a much more challenging environment.28 Meanwhile, the Caribbean market was easily accessible; there was much less competition and business was unregulated.

The unregulated market allowed Sun Life to protect its foreign operations from the high risks of international investment. The Canadian company mandated that foreign business be self–supporting and not financed or supported by domestic premiums; therefore, business risks were assumed by each Latin American office and policies were tailored to the particular needs and perils of each case.29

Sun Life also benefited from the failed attempts of several American insurance companies. In 1922, American–owned Equitable Life Insurance Company reinsured their existing Colombian policies with Sun Life, and in 1923 New York Life Insurance Company followed suit.30 By 1927 Sun Life Assurance had successfully expanded its operations to include a broad share of the international market.31 Foreign markets such as Colombia were so important that the president at the time said, "Canadian business, large though it is, will soon be less than ten per cent of the total profits are being earned by Canadian brains and Canadian enterprise, but not from Canadian premiums."32

Sun Life took advantage of Colombia's 1920s "dance of the millions."33 It generated business from the inflow of capital that stemmed from Washington's 1921 reparation payment for the loss of Panama and the increase of American foreign investment, as seen in the case of the United Fruit Company.34

The presence of American companies and Canadian subsidiaries such as Tropical Oil and Andian National Corporation turned Barranquilla into a promising insurance market.35 Cartagena was also an important business hub for Sun Life Assurance. The historic port city was a desired destination for Canadian winter cruises that sailed the Caribbean. Cartagena's tourist industry represented an important market for foreign companies such as Sun Life; the city offered a concentrated core of traditional wealth, an emerging merchant class, and a strong presence of foreigners that tailored to the needs of a growing tourist industry.36

By 1930 three foreign–owned companies controlled close to fifty–four percent of Colombia's insurance market; Sun Life's policies represented half of this share and the rest was split between Manufacturers Life and New Orleans–based Pan American Life Insurance Company.37 By that time, the Colombian life insurance market was, for the most part, underwritten by Canadians.

However, the Great Depression forced President Enrique Olaya Herrera to implement a series of nationalist policies that conflicted with the interests of foreign companies operating in Colombia. Protectionist policies such "as placing the oil industry under government regulation" sent a negative message to Canadian insurance companies.38 Additionally, the fine–tuning of risk evaluation that resulted from the outcomes of the First World War lead Sun Life and Manufacturers to reevaluate their position in Colombia and other parts of the hemisphere. In the 1930s, for example, "Sun Life Assurance of Canada opened no new offices in the United States and closed thirteen. It withdrew from underwriting insurance in Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Dutch Guiana (Surinam), French Guiana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru."39 However, this did not impede the company from growing its insurance business elsewhere. T.B. Macaulay, president of the company at the time, reported shareholder gains "of more than $36,000,000 in assets" for 1931, and highlighted the possibility of expanding business to the recovering North American market.40 Canadian insurance companies had changed their strategy, moving away from Latin America and concentrating on Canadian and American markets.

Latin America was no longer an attractive market due to nationalist policies. In Colombia, protective policies threatened foreign business interests, and the possibility of social unrest and political instability created a less than favorable environment for insurance companies. After the 1930s Colombia had become an unstable place, and the debate over sovereignty and oil policy reduced the interest of foreign investors. Sun Life and other foreign corporations only considered returning to Colombia after the Frente Nacional policies of 1958 that favored open market and business–friendly initiatives.

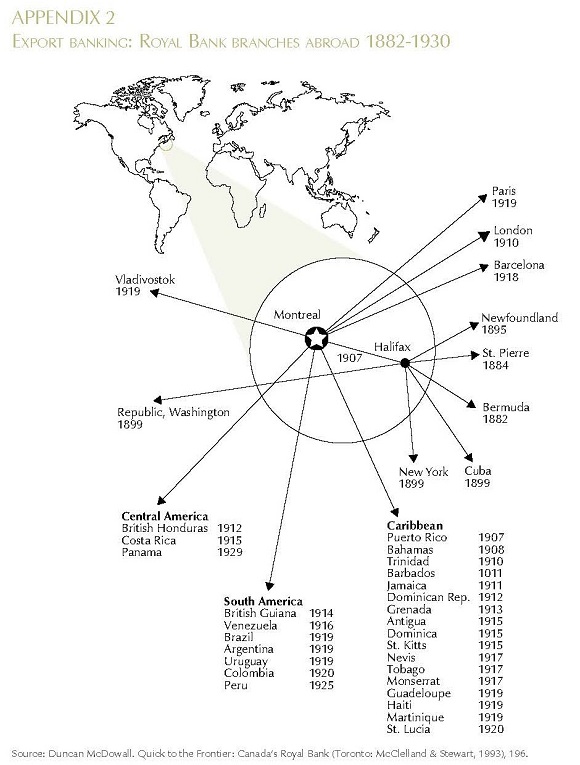

III. Banking

Canadian banks were able to successfully penetrate the Latin American and Caribbean markets for two main reasons: the support they received from their federal government, and the knowledge of their leaders concerning the changing dynamics of geopolitical power in the region. Specifically, former Royal Bank president Sir Herbert Holt was instrumental in helping the bank navigate the murky waters of the struggle for imperial power in the Western Hemisphere. The bank aggressively entered the market in 1920 with the objective of carrying out branch banking operations across the country, and was able to remain a personal banking operation for the next forty years. In the 1960s, Royal Bank would begin to experiment with investment banking through consortium banking, following the footsteps of Bank of London and Montreal, which entered the Colombian market with mixed banking products in the late 1950s.41

In the early twentieth century, institutions such as Royal Bank received Ottawa's approval to expand beyond national borders, unleashing international banking operations that "boomed in the 1920s, assisted directly and indirectly by provincial and federal governments that were eager to facilitate the country's expansion."42 The efforts of Royal Bank of Canada, Bank of Nova Scotia, and Bank of Montreal contributed to Canada's rapid economic development of the 1920s, aided by increased federal powers that orchestrated economic production and centralized banking policy in Ottawa.43

Ottawa used flexible and more progressive banking legislation to ensure that banking contributed not only to national economic development but also to the consolidation of the nation state as well. Policy makers established a stable industry that would encourage the inward flow of capital, therefore choosing "chartered banks as the dominant financial institution in Canada."44 Contrary to other industries, banking became a Canadian–controlled industry designed to facilitate provincial and international trade; its infrastructure was intended to assist government financing.45

Meanwhile, banks in Britain and the United States were restrained from expanding operations abroad. Prior to the First World War "there was no American bank in Latin America, the law forbidding Federal banks to establish branches abroad."46 However, as the war progressed and the British Empire's influence in the region decreased, Washington quietly stepped up to fill the gap being left by Britain. British and Canadian bankers and policy makers were well aware of these changes.

The initial developments of the Pan American Union led British officers to believe that Americans were forming an American League of Nations to displace them from the region. In the case of banking, they pointed out that during the war restrictive laws were "quietly changed" by the American government "to permit the financiers of Wall Street to invade South American markets and dominate them."47 They accused the Americans of intervening in the private and government affairs of Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, and Colombia.48 Taking advantage of the declining influence of British banks, Canadian institutions aggressively increased their activity across the region in order to compete against American banks.

During the 1915 Pan American Financial Conference held in Washington, delegates from Latin America indicated "they needed many commodities which they formerly bought from Europe."49 However, they doubted that the American system could take "the position in South American finance held for so long by European countries, particularly England."50 Unable to distinguish between the Canadian Dominion and the British Empire, lobbyists from the region's financial sector had no other option but to take their agenda to the United States. Prominent bankers, national bank directors, and Treasurers took advantage of the opportunity to lobby for the "establishment of banks, arrangement of credits, and temporary investment in such directions as the supplying of money for the working of mines and rubber plantations, and extending to South American traders those credit facilities" that had been closed as a result of the war.51

In the case of Colombia, delegate Santiago Pérez Triana arrived with a proposal that stipulated, in great detail, the type of foreign banking that would benefit the region.52 He explained:

• Autonomous banks, in my view, should be established in each South and Central American country under the guarantee of the respective countries. These should be individual banks, having no connection with one another. All the banks should be under the auspices of a general United States banking association, composed of banks and bankers of the various parts of your country, or else each individual new bank should be under the auspices of an individual bank or group of bankers of the United States.53

Royal Bank and all other Canadian banks that entered Latin American and Caribbean markets in response to the demand of banking and financial services fulfilled the requirements set forth by Triana. Institutions such as Royal Bank were eager to tackle the challenge set forth by the members of the Pan American Union.

By 1916, just one year after the Pan American Financial Conference, the Royal Bank of Canada had opened branch operations in Cuba, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela.54 That year Holt visited Cuba, Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, Costa Rica, and the British West Indies with the intention of familiarizing himself "with local conditions and to meet leading customers."55 He also visited Venezuela, where the bank had just opened its first branch, and stopped in Colombia to discuss with local authorities and the British government the possibilities of opening branch offices there as well.56 Later, at the bank's annual meeting, he reported to shareholders that "he was gratified to receive from Viscount Grey, the late (British) Foreign Secretary, his approval of the establishment of branches" in Colombia.57

By the war's end, Royal Bank of Canada was well positioned across the hemisphere. The bank profited from Holt's understanding of the region; he not only was familiar with the geopolitical realities and the business culture, he also understood the importance of taking advantage of the window of opportunity that Canadian banks had to compete shoulder to shoulder with American counterparts.

The war benefited Latin American and Caribbean economies by allowing them to diversify their pool of foreign investors. It provided an opportunity for Americans to displace European banks from the region and, according to Holt, it had revealed to Canadians their "economic power" and provided a "great opportunity in the field of foreign trade."58

By 1920, when the bank first began operations in Colombia, it provided personal banking services, including intermediary banking between Colombia and Europe.59 This was crucial because most European–owned banks operating in Colombia had closed, leaving behind a demand from commodity consumers, foreign and local merchants, and exporters that still relied heavily on the European market. Royal Bank was able to maintain this relationship and serve as a bridge between Colombia and Europe. This was a great advantage because American banks at the time could not provide intermediary services with Europe. Royal Bank capitalized on this opportunity to expand its branch services across Colombia.

The bank's efforts in the region motivated others in the Canadian private sector to reevaluate business opportunities in the region. In 1921, the Canadian Manufacturers Association embarked on a fact–finding mission throughout the West Indies and South America. Upon their return, Canadian exporters, importers, and representatives from the manufacturing sector met in Montreal to debrief on the recent visit. In regards to banking, they noticed that Canadian banks were well positioned, particularly the Royal Bank.60 C.E. Austin, a Canadian business representative living in Barranquilla, referred specifically to business in South America. He noted that Colombia and Venezuela "were now at the commencement of what promises to be a remarkable period of expansion," thanks in part to the development of the Panama Canal.61 Once again, representatives from the Canadian business and manufacturing sector concluded that Ottawa needed to increase its efforts, and suggested the government send men to the region "to keep in touch with conditions in that part of the world and establish business connections."62 If there was more government presence in the region, the delegation concluded, trade relations would be greatly benefited.63

Herbert Holt was also interested in receiving direct support from the Canadian government, particularly after 1922 when the American–owned Bank of Central and South America took over all branch operations of Mercantile Bank of the Americas for Central and South America.64 This meant that National Bank of Nicaragua, Banco Mercantil de Costa Rica, Banco Mercantil Americano del Perú, Banco Mercantil Americano de Caracas, and Banco Mercantil Americano de Colombia were now controlled by American interests.65 With British banks out of the picture, American and Canadian banks were left on their own to compete against local banks.

Herbert Holt, who had a particular affinity for Venezuela and Colombia, never gave up the fight for the control of these newly–developed markets.66 In an effort to convince the bank's board members, Canada's private sector, and Ottawa of the benefits of defending their position in Colombia, Holt emphasized the potential of Colombia's untapped wealth. Royal Bank issued a national report published in 1925 that indicated there were "few storehouses of untouched and unmeasured wealth to compare with the resources that remain to be developed in the Republic of Colombia."67 Regarding the nation's financial situation, the report concluded that Colombia's international debt of close to twenty–two million dollars for 1924 was not a significant figure and that the banking industry was sound, thanks to the establishment "of the central reserve bank modeled after the Federal Reserve system."68 Rapid economic development, said the report, had not been achieved because of the limited development of land transportation and other transportation facilities.69 The report concluded that the development of the commercial hydroplane industry had represented a step forward, but in order to unify the country's economy, a railroad system needed to be developed and the Bank could facilitate this venture.70 Since the Germans had beaten them to the development of an air travel industry, pitching the idea of a national railroad system was the next best economic development business option. The Royal Bank had experience with the development of national railway networks in Canada and therefore saw this as a possible investment option.

In an effort to win the race for Colombia's untapped markets, foreign companies, including the Royal Bank, began to look closer at the Colombian Andean markets after the development of an air travel industry by German ex–Luftwaffe pilots significantly reduced travel time from the Colombian coast to the interior.71 This facilitated the business of Royal Bank of Canada, Sun Life Assurance and all other foreign financial and domestic entities operating in Colombia at the time. Air travel expanded market opportunities and accelerated financial sales operations and transactions in the Colombian market. For Colombia, the establishment of air travel represented an advantage over other Latin American and Caribbean countries that were interested in attracting foreign capital. This represented a tremendous achievement for the German business sector considering their weaker position in the hemispheric market, particularly in Colombia where Americans were beginning to dominate. German ingenuity and the ability to identify and fill the gaps left by British and American investors served as an example for Canadian businesses interested in tapping what Holt referred to as "the vast stretches about which little is known and the possibilities of which have been only vaguely suggested."72

Herbert Holt insisted on defending the company's interests in Colombia. In February of 1925 Royal Bank "purchased all of the shares of the Bank of Central and South America," thereby expanding its outreach in the region.73 The Bank of Central and South America, which had been in the market for just three years, found itself in financial trouble and unable to successfully carry out business in Latin America. Holt relished the opportunity to establish greater distance between the Americans and the Royal Bank in the region. He incorporated the branches of the Bank of Central and South America into the branch network of the Royal Bank.74 The Canadian entity had, by that point, been singled out as "one of the largest competitors of American banks doing business in Latin America."75 This was more evident after his decision to absorb seventeen more branches in the region.76

In order to carry out the bank's objectives in Colombia, Holt requested greater support from Ottawa. He needed the Canadian government to increase its efforts in the region. After Holt's Latin American tour in 1925, bank officials who accompanied Holt reported that Canadian trade commissioners in South America were "hampered and handicapped" by the limited resources available for public relations.77 The bank demanded greater government involvement as public relations and diplomacy began to play a bigger role in the region. However, the Mackenzie King administration remained committed to its East–West relations and was "apprehensive about external commitments," particularly in Latin America.78

In 1927 the bank once again registered record growth.79 Holt's report to the board of directors indicated that it represented "the most successful year in the history of the bank."80 He credited part of the growth to its operations in Latin America and the Caribbean.81

Colombia was among those markets highly regarded by Royal Bank, not only for their contribution to business expansion, but because of their potential for further growth. Ottawa recognized this as well and in 1927 included Colombia as part of the official itinerary of the trade mission headed by Deputy Minister of Trade and Commerce F.C.T. O'Hara.

The official mission was a sign that Ottawa had responded to Holt's and the Manufacturers Association's demand for increased official support in the region.82 O'Hara, who possessed "sufficient working knowledge of the Spanish language," left in the fall on a four–month tour that stopped in Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Colombia.83

Holt's lobbying efforts for their operation in Colombia coupled with the increasing presence of Imperial Oil and Andian National Corporation resulted in a small but determinant role of Colombia within Canada's trade and foreign policy agendas. By the early 1930s bilateral trade with Colombia and other Latin American and Caribbean nations began to have a positive impact on Canada's economic growth. Canada's exports reached unprecedented levels of growth; they increased from US$3,312,000 in 1933 to US$13,803,000 in 1934, culminating in a total of US$16,936,000 by 1935.84 Canada also became a major destination for Colombian exports, in particular coffee and oil.85

Royal's experience in Colombia showed that the nation's decision makers were eager to accelerate Canada's participation in the international market system. Colombia's growth had caught the attention of global investors, and its business culture was being recognized by the international business sector as one of "forward–looking spirit imbued with an admiration of North American enterprise and methods."86

Although the Royal Bank was able to overcome the obstacles imposed by the nationalist agenda of the Liberal administrations that followed the Great Depression, it did not fare as well with the impacts that the Second World War had on Colombia. The presence of German U–Boats in the Caribbean forced the Canadian subsidiary Imperial Oil to shift its oil imports from Barrancabermeja to their operations in Venezuela. The reduced presence of Royal Bank's biggest ally in Colombia impeded the advancement of their aggressive business campaign. Although it did not close its branch operation, it did retract from further expansion. This allowed Americans to fill the market gap left by Holt.

After the war, Royal Bank began to reclaim its position in the Latin American and Caribbean markets. An ad in the Winnipeg Free Press summarized its intention:

• Before the war at least 25c out of every dollar of Canadian income was derived from exports. How much income, and how many jobs for Canadian workers, will exports provide after the war? That will depend partly on how much we buy abroad. It will depend, too, on how effectively we develop present markets and search out new ones. The Royal Bank of Canada can assist both buyers and sellers. In Caracas, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and 16 other important Central and South American cities, our branches provide on–the–ground information about export markets and sources of supply.87

Royal Bank's return to the Latin American market encountered the fierce competition of American banks that were also interested in expanding business throughout their sphere of influence.

IV. Banking Under U.S. Hegemony

The Cold War that unfolded after the Second World War, coupled with the expansion of open market capitalism across the region, led the United States to reevaluate its hemispheric foreign policy. Canada, as a middle power, had to accommodate to the conditions set by Americans and accept its junior partnership role.88 From then on, Canada lost maneuverability and had to leave the Royal Bank's fortune in the hands of the free market. Nevertheless, the bank's predominant presence in places like Colombia during the first half of the twentieth century and its collaboration with Imperial Oil and the Andian National Corporation left an enduring mark on the bilateral relationship.

Canadian financial institutions played a key role in the development, expansion, and structure of the Colombian financial system. Together with British and American institutions, they cemented the pillars for the "long–term trend towards larger markets that transcend political boundaries."89 Colombia, as part of the transnational business of Canadian financial institutions, provided the capital for the development and growth of the Canadian economy. Institutions such as Sun Life Assurance and Royal Bank expanded their business abroad in order to keep profits inside Canada and avoid capital flight that resulted from their subsidiary role.90 Emerging consumer markets like Colombia's served as launching grounds for the nationalist efforts carried out by Canadian financial institutions abroad.

Financial institutions created the need for an increased presence of the Canadian government within the region. They forged a national image abroad that Ottawa had not been able or even intended to promote in the region. Under the guidance of individuals such as Herbert Holt, Canadians were able to realize that the best way to distinguish themselves from the competition was by branding the "Canadian" name abroad. Together with Canadian oil and gold mining subsidiaries, commercial institutions came to the conclusion that Colombia was a relatively untapped market where Canada could establish a clear–cut line of action.

Washington and American private interests were also well aware of the vast investment opportunities that lay idle across the Colombian territory. The 1950 World Bank mission to Colombia headed by Lauchlin Currie confirmed the nation's potential for growth and development. American influence on the economic development and institutional modernization of Colombia made it more difficult for Canadian financial entities to capitalize on the nation's accelerated growth of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. The adoption and implementation of free market policies under the Frente Nacional administrations, the expansion of a domestic financial market, and the recovery of the European market also made it more difficult for Canadian financial entities to compete effectively. Canadian financial companies remained active in Colombia, but their share of the market never reached the record levels of the early 1900s. In 1958 the Bank of London and Montreal established a banking operation in Colombia.91 By 1963 their operation had expanded across Latin America, and Colombia had become their biggest South American operation with a total of six branch offices.92 However, their share of Colombia's domestic banking was minimal and their participation in the nation's economic development and modernization of the second half of the twentieth century was even less. The inflow of American capital after the Second World War, Washington's vigilance over their sphere of influence, a nationally–controlled domestic financial market, and a lack of interest from Canadian financial powerhouses negated any possibilities of a strong Canadian comeback during the rest of the twentieth century.93

Comments

1 Graeme Mount, "Canadian Investment in Colombia: Some Examples, 1919–1939," North/South: The Canadian Journal of Latin American Studies, 1, no. 1 and 2 (1976): 46.

2 Frank Safford, "Foreign and National Enterprise in Nineteenth–Century Colombia," The Business History Review 39, no. 4 (Special Latin American Issue) (Winter 1965): 521.

3 For more on Bank of London and Banco de Bogotá see Safford, "Foreign and National Enterprises in Nineteenth–Century Colombia," 521. For information on Banco Alemán Antioqueño, Anglo South American Bank, and French and Italian Bank, see Adolfo Barajas, Roberto Steiner, and Natalia Salazar, "Foreign Investment in Colombia's Financial Sector," (Bogota: International Monetary Fund, November 1999), 5.

4 Gregory P. Marchildon, "Canadian Multinationals and International Finance: Past and Present," Business History 34, no. 3 (July 1992): 3.

5 Ibid., 2.

6 By the early 1900s, elites from Barranquilla and Cartagena had established strong relations with foreign businesses and investors. Their economic development had become more dependent on foreign markets than on the domestic market, as companies such as United Fruit and the Andian National Corporation invested in infrastructure proyects geared towards the region's export economy. For more on the region's economic development during the early 1900s, see Adolfo Meisel Roca, ¿Por Qué Perdió la Costa Caribe el Siglo XX? Y Otros Ensayos (Bogotá: Banco de la República, 2011), 133–68.

7 James L. Darroch, "Global Competitiveness and Public Policy: The Case of Canadian Multinational Banks," Business History 34, no. 3 (July 1992): 153.

8 Graeme Mount, "Canadian Investment in Colombia: Some Examples, 1919–1939," North/ South: The Canadian Journal of Latin American Studies 1, no. 1 and 2 (1976): 46.

9 Sun Life established business in Panamá in 1904 and Manufacturers followed in 1909. By that point Panama had gained independence from Colombia. Graeme Mount, "Isthmian Approaches: The Trajectory of Canadian–Panamanian Relations," Caribbean Studies 20, no. 2 (1980): 51–52.

10 Vernon Lee Fluharty, Dance of the Millions: Military Rule and the Social Revolution in Colombia (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1957), 23.

11 Toronto Head Office, Canada, "Manufacturers Life Insurance Company," The Daily Gleaner, March 20, 1901, 7.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Manufacturers' operations in other parts of the Caribbean and South America were initially based in Jamaica. Ivanhoe Gadpaille, "Manufacturers Life Insurance Company of Canada," The Gleaner, April 29, 1902, 6.

17 This includes Latin American and Caribbean nations such as Cuba, Haiti, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, Chile, and Argentina. See George H. Harris, The President's Book: The Story of the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada (Montreal: Sun Life Assurance Company, 1928), viii–ix.

18 Total trade between Colombia and the United States was insignificant, it "amounted to a little more than a million dollars in 1830, reached two million in 1855 and fourteen million in 1880, but declined to seven million in 1900." This tendency would begin to change after the First World War. J. Fred Rippy, The Capitalists and Colombia (New York: The Vanguard Press, 1931), 10.

19 Mount, "Canadian Investment in Colombia: Some Examples, 1919–1939," 46.

20 Harris, The President's Book: The Story of the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, 83.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid., 84.

23 Ibid., 87.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Regional historian Eduardo Posada–Carbó made reference to what C.A. Jones called Barranquilla's "cosmopolitan bourgeoisie", a merchant class of mixed nationalities. For more on Barranquilla's elites, see Posada–Carbo, The Colombian Caribbean: A Regional History, 1870–1950, 208. For more on Barranquilla's contribution to Colombia's national economy during the early 1900s, see Adolfo Meisel Roca, ¿Por Qué Perdió la Costa Caribe el Siglo XX? Y Otros Ensayos, 134–44.

27 According to company records, Colombia was seen as an untapped market; for more information see Harris, The President's Book, 87.

28 Harris, The President's Book: The Story of the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, 88.

29 Ibid., 126.

30 Mount, "Canadian Investment in Colombia: Some Examples, 1919–1939," 47.

31 By 1927 Sun Life Assurance was present in the United States, Great Britain, Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Argentina, Peru, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, Haiti, British West Indies, Japan, India, China, Egypt, Philippines and South Africa. "Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada: A great international institution," The Gleaner, March 3, 1928, 17.

32 Mira Wilkins, "Multinational enterprise in insurance: An historical overview," Business History, 51, no. 3 (May 2009): 343.

33 For more information on the "dance of the millions", see Vernon Lee Fluharty. Dance of the Millions: Military Rule and the Social Revolution in Colombia (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1957).

34 J. Fred Rippy indicated that U.S. direct investment in Colombia experienced a rapid expansion, going from "11 million dollars in 1910 to 23 million in 1913, more than 112 million in 1920, and over 153 million in 1929"; for more detail see Rippy, The Capitalists and Colombia, 14. In the case of United Fruit, investments in Colombia had escalated from an initial $2 million to $125 million by 1928; see "Progress made by United Fruit Company in the Caribbean," The Gleaner, March 27, 1928, 6.

35 For more on the Andian National Corporation and its presence in Colombia see Adolfo Meisel Roca, ¿Por Qué Perdió la Costa Caribe el Siglo XX? Y Otros Ensayos, 151–54; see also Stefano Tijerina, "A 'Clearcut Line': Canada and Colombia, 1892–1979" (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Maine, 2010), 49–67.

36 Numerous American and Canadian cruise lines used newspaper advertisements as a means to market their product. A 1924 ad in the Manitoba Free Press showed the key destinations of the Canadian Red Star Line, the White Star, and the Dominion Line. In this case, as in many others, Cartagena was included as a key destination in the Caribbean. See "Winter Cruises," Manitoba Free Press December 2, 1924, 16.

37 Mount, "Canadian investment in Colombia," 47.

38 Fluharty, Dance of the Millions, 43.

39 Wilkins, "Multinational enterprise in insurance," 344.

40 "Assets of Sun Life Rise $36,000,000," New York Times February 10, 1932, 35.

41 The Bank of London and Montreal was jointly formed by the Bank of Montreal and the Bank of London and South America; for more detail see Duncan McDowall, Quick to the Frontier: Canada's Royal Bank (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1993), 409.

42 Scott W. See, The History of Canada (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2001), 116.

43 Ibid., 108.

44 Ibid., 154.

45 James L. Darroch, "Global Competitiveness and Public Policy: The Case of Canadian Multinational Banking," Business History 34, no. 3 (July 1992).

46 Edwin L. James, "Europe Watching Pan–America Plans," New York Times March 27, 1923, 19.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

49 "South America Needs the U.S.," New York Times, May 23, 1915, SM 12.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 Triana was a prominent Colombian banker, former Minister to Great Britain, and son of a former Colombian President.

53 "South America needs the U.S.," SM 12.

54 Herbert Holt, "Forty–Eighth Annual Meeting of the Royal Bank of Canada," Manitoba Free Press January 19, 1917, 12.

55 Ibid.

56 Ibid.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 "The Royal Bank of Canada has formed a close working association with the London County Westminster and Parr's Bank, Limited," The Gleaner, July 11, 1919, 7.

60 Canadian Gazette, "Trade between Dominion and West Indies," The Gleaner, December 29, 1922, 6.

61 Ibid.

62 Canadian Gazette, "Trade between Dominion and West Indies," The Gleaner December 29, 1922.

63 Ibid.

64 "Bank to specialize in Latin America," New York Times, September 15, 1922, 31.

65 Ibid.

66 See Appendix 1.

67 "Colombia's riches reviewed by Bank," New York Times, July 3, 1925, 24.

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid.

70 Ibid.

71 German investors were instrumental in the development of the first commercial airline industry to operate in Colombia. SCADTA (Colombo–German Society of Air Transportation) was also the first commercial airline to be established in Latin America. See Fluharty, Dance of the Millions, 35.

72 "Colombia's riches reviewed by Bank," 24.

73 "Bank of Canada is spreading out," The Gleaner, March 30, 1925, 19.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 "Bank of Canada adds to holdings," New York Times, February 4, 1925, 33.

77 Hill, Canada's Salesman to the World: The Development of Trade and Commerce, 1892– 1939, 411.

78 Paul Painchaud, ed. From Mackenzie King to Pierre Trudeau (Québec: Les Presses de L'université Laval, 1989), 15.

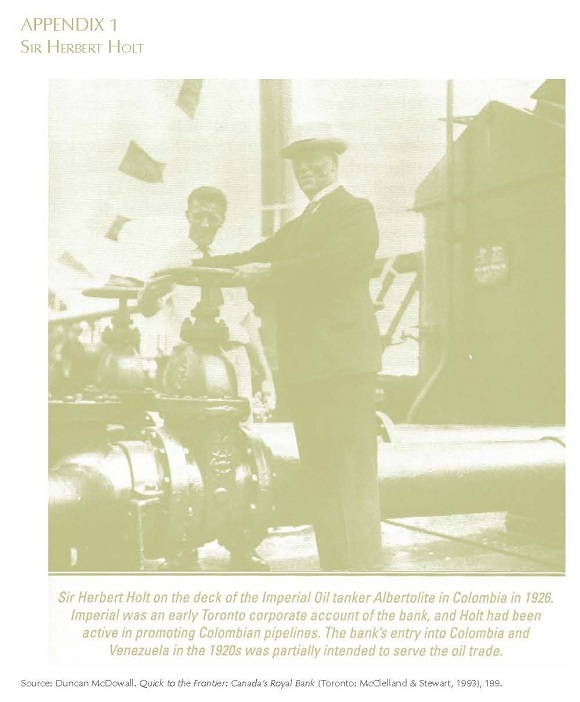

79 See Appendix 2.

80 Herbert Holt, "Fifty–ninth annual meeting of the Royal Bank of Canada," New York Times, January 17, 1928, 47.

81 Ibid.

82 "Trade mission from Canada is planned," The Daily Gleaner, May 19, 1927, 1.

83 Ibid.

84 Dispatch Canadian Press, "Rise in Canadian exports," New York Times, June 5, 1935, 28.

85 By 1938 Canada was ranked fourth among Colombia's export destinations with 8.7 percent of total exports. In 1941 Canada was second to the United States with an export market share of 13.2 percent, but in 1942 exports to Canada dropped to 1.5 percent as a "result of shipping restrictions and wartime trade regulations." See "Postwar Trade Reviews: Colombia and Venezuela," (Ottawa: Department of Trade and Commerce, 1946), 6.

86 "Colombia imbued with enterprise of North," The Lethbridge Herald, December 24, 1930, 3.

87 "Foreign trade means work for Canadians," Winnipeg Free Press, April 4, 1945, 7.

88 For more on Canada's middle power role, see John W. Holmes, ed. Canada: A Middle–Aged Power (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1976).

89 Marchildon, "Canadian multinationals and international finance," 1.

90 George H. Harris indicated that during the first board of directors meeting of Sun Life, one of the Directors, Mr. Workman, said that "he hoped that the desire to build up Home Institutions by prudent management would be speedily realized, so that the confidence of our people in the stability of our own institutions might be secured, and the million and a half dollars that now go out of the country to build up foreign cities may be kept at home to build up the resources of the Dominion." Harris, The President's Book, 57.

91 Daniel Jay Baum. The Banks of Canada in the Commonwealth Caribbean: Economic Nationalism and Multinational Enterprises of a Medium Power (New York: Praeger, 1974), 23.

92 Ibid.

93 In the 1960s, Quebec and British interests came together to form the Bank of London and Montreal. The partnership absorbed the branch offices of Bank of London and South America in Colombia, and operated in that market until 1970. It would take another forty–two years before another Canadian bank would penetrate the Colombian consumer market. In January 2012, Scotiabank purchased 51 percent of Banco Colpatria de Colombia, adding to its Latin American operations which also included Chile, Peru, and Mexico.

REFERENCES

1. "Assets of Sun Life Rise $36,000,000", New York Times, February 10, 1932. [ Links ]

2. "Bank of Canada Adds to Holdings", New York Times, February 4, 1925. [ Links ]

3. "Bank of Canada Is Spreading Out", The Gleaner, March 30, 1925. [ Links ]

4. "Bank to Specialize in Latin America", New York Times, September 15, 1922. [ Links ]

5. Barajas, A.; Steiner, R.; Salazar, N. Foreign Investment in Colombia's Financial Sector, Bogotá, International Monetary Fund, 1999. [ Links ]

6. Baum, D. J. The Banks of Canada in the Commonwealth Caribbean: Economic Nationalism and Multinational Enterprises of a Medium Power, New York, Praeger, 1974. [ Links ]

7. Braun, H. Mataron a Gaitan, Bogotá, Editora Aguilar, 2008. [ Links ]

8. Canadian Press, Dispatch. "Rise in Canadian Exports", New York Times, June 5, 1935. [ Links ]

9. "Colombia Imbued with Enterprise of North", The Lethbridge Herald, December 24, 1930. [ Links ]

10. "Colombia's Riches Reviewed by Bank", New York Times, July 3, 1925. [ Links ]

11. Darroch, J. L. "Global Competitiveness and Public Policy: The Case of Canadian Multinational Banking", Business History, vol. 34, num. 3, pp. 153-175, 1992. [ Links ]

12. Fluharty, V. L. Dance of the Millions: Military Rule and the Social Revolution in Colombia, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1957. [ Links ]

13. "Foreign Trade Means Work for Canadians", Winnipeg Free Press, April 4, 1945. [ Links ]

14. Gadpaille, I. "Manufacturers Life Insurance Company of Canada", The Gleaner, May 24, 1913. [ Links ]

15. Gazette, C. "Trade between Dominion and West Indies", The Gleaner, December 29, 1922. [ Links ]

16. Gootemberg, P. Between Silver and Guano: Commercial Policy and the State in Postindependence Peru, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1989. [ Links ]

17. Harris, G. H. The President's Book: The Story of the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, Montreal, Sun Life Assurance Company, 1928. [ Links ]

18. Head Office, Toronto, Canada. "Manufacturers Life Insurance Company", The Daily Gleaner, March 20, 1901. [ Links ]

19. Henderson, J. D. Modernization in Colombia: The Laureano Gomez Years, 1889-1965, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2001. [ Links ]

20. Hill, M. O. Canada's Salesman to the World: The Development of Trade and Commerce, 1892-1939, Montreal, McGill-Queens University Press, 1977. [ Links ]

21. Holmes, J. W. Canada: A Middle-Aged Power, Toronto, McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1976. [ Links ]

22. Holt, H. "Forty-Eighth Annual Meeting of the Royal Bank of Canada", Manitoba Free Press, January 19, 1917. [ Links ]

23. James, E. L. "Europe Watching Pan-America Plans", New York Times, March 27, 1923. [ Links ]

24. Marchildon, G. P. "Canadian Multinationals and International Finance: Past and Present", Business History, vol. 34, num. 3, pp. 1-15, 1992. [ Links ]

25. Marichal, C. A Century of Debt Crises in Latin America: From Independence to the Great Depression, 1820-1930, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1989. [ Links ]

26. McDowall, D. Quick to the Frontier: Canada's Royal Bank, Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1993. [ Links ]

27. Mount, G. "Canadian Investment in Colombia: Some Examples, 1919-1939", North/South: The Canadian Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 1, num. 1 and 2, pp. 46-61, 1976. [ Links ]

28. Mount, G. "Isthmian Approaches: The Trajectory of Canadian-Panamanian Relations", Caribbean Studies, vol. 20, num. 2, pp. 49-60, 1980. [ Links ]

29. Painchaud, P. From Mackenzie King to Pierre Trudeau: Forty Years of Canadian Diplomacy, 1945-1985, Quebec, University of Laval Press, 1989. [ Links ]

30. Posada-Carbo, E. The Colombian Caribbean: A Regional History, 1870-1950, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1996. [ Links ]

31. "Postwar Trade Reviews: Colombia and Venezuela", Ottawa, Department of Trade and Commerce, 1946. [ Links ]

32. "Progress Made by United Fruit Company in the Caribbean", The Gleaner, March 27, 1928. [ Links ]

33. Rippy, J. F. The Capitalists and Colombia, New York, The Vanguard Press, 1931. [ Links ]

34. Meisel, A. ¿Por qué perdió la Costa Caribe el siglo XX? Y otros ensayos, Bogotá, Banco de la República, 2011. [ Links ]

35. Safford, F. "Foreign and National Enterprise in Nineteenth-Century Colombia", The Business History Review, vol. 39, num. 4 (Special Latin American Issue), pp. 503-526, 1965. [ Links ]

36. See, S. W. The History of Canada, Westport, Greenwood Press, 2001. [ Links ]

37. "South America Needs the U. S.", New York Times, May 23, 1915. [ Links ]

38. "Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada: A Great International Institution", The Gleaner, March 3, 1928. [ Links ]

39. "The Royal Bank of Canada Has Formed a Close Working Association with the London County Westminster and Parr's Bank, Limited", The Gleaner, July 11, 1919. [ Links ]

40. Tijerina, S. "A 'Clearcut Line': Canada and Colombia, 1892-1979", Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Maine, 2010. [ Links ]

41. "Trade Mission from Canada Is Planned", The Daily Gleaner, May 19, 1927. [ Links ]

42. Wilkins, M. "Multinational Enterprise in Insurance: An Historical Overview",Business History, vol. 51, num. 3, pp. 334-363, 2009. [ Links ]

43. "Winter Cruises", Manitoba Free Press, December 2, 1924. [ Links ]

APPENDIX

1. Sir Herbert Holt

2. Export banking: Royal Bank branches abroad 1882–1930