Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

Print version ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.32 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2017

https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.173

Original articles

Susceptibility of Helicobacter Pylori to Antibiotics: a Study of Prevalence in Patients with Dyspepsia in Quito, Ecuador

1Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública “Leopoldo Izquieta Pérez”, Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Central del Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador.

2Escuela de Bioanálisis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador.

3Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública “Leopoldo Izquieta Pérez” Escuela de Bioanálisis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador.

4Hospital de las fuerzas Armadas n.° 1. Quito, Ecuador.

5Hospital de Especialidades Eugenio Espejo. Quito, Ecuador.

Introduction:

Worldwide, helicobacter pylori is associated with gastrointestinal pathologies, but increasing resistance to antibiotics used for its eradication is causing alarm. This study determined susceptibility of H. pylori to five antibiotics used in eradication therapy in an adult population with recurrent dyspepsia in Quito, Ecuador.

Materials and methods:

After patients provided informed consent, biopsies were taken from the gastric corpus and fundus of 210 patients with dyspepsia. H. pylori isolates identified by biochemical tests were recovered from cultures of biopsy samples. Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline and levofloxacin were tested to indicate susceptibility. All cultures were correlated with the histopathological study.

Results:

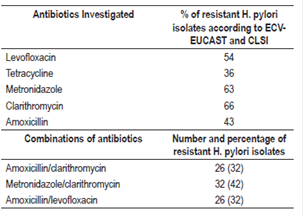

H. pylori isolates were recovered from 89 cultures. A kappa of 0.9 was obtained between the culture and the histopathological study. The percentage of strains with antibiotic resistance were 63% for metronidazole, 66% for clarithromycin, 43% for amoxicillin, 36% for tetracycline and 54% for levofloxacin.

Conclusion:

These findings demonstrate high levels of resistance to the antibiotics used for eradication of H. pylori. Several factors including indiscriminate consumption of antibiotics and previous therapy may be involved.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori; antibiotic resistance; minimal inhibitory concentration.

Introducción:

el Helicobacter pylori se asocia con patologías gastrointestinales, el incremento en la resistencia a los antibióticos utilizados para su erradicación es alarmante a nivel mundial. En este estudio se determinó la susceptibilidad a 5 antibióticos utilizados en la terapia de erradicación de H. pylori aislado de una población adulta con dispepsia recurrente en Quito, Ecuador.

Materiales y métodos:

previa aceptación del consentimiento informado, se tomaron biopsias de cuerpo y fondo gástrico de 210 pacientes con dispepsia y mediante cultivo se recuperaron los aislados de H. pylori identificado mediante pruebas bioquímicas. La susceptibilidad al metronidazol, claritromicina, amoxicilina, tetraciclina y levofloxacina se realizó por concentración mínima inhibitoria (CMI). Todos los cultivos se correlacionaron con el estudio histopatológico.

Resultados:

se recuperaron 89 aislados de H. pylori. Se obtuvo un kappa de 0,9 entre el cultivo y el estudio histopatológico. El porcentaje de cepas con resistencia antibiótica fue: metronidazol (63%), claritromicina (66%), amoxicilina (43%), tetraciclina (36%) y levofloxacina (54%).

Conclusión:

estos hallazgos demuestran la alta resistencia a los antibióticos usados para la erradicación de H. pylori, varios factores como el consumo indiscriminado de antibióticos, terapia previa, entre otros podrían estar involucrados.

Palabras clave Helicobacter pylori; resistencia antibiótica; concentración mínima inhibitoria

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacillary bacterium that inhabits the gastric mucosa and is associated with inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases such as peptic ulcers, chronic gastritis and neoplasms such as MALT (mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue). Production of cytotoxins is associated with genes A (cagA) and the vacuolizer allele (vacA). 1,2 H. pylori is acquired during childhood and remains asymptomatic for many years. Close contact is a risk factor. 3,4 Studies have shown that the prevalence of H. pylori in adults in developing countries exceeds 70%, 5 but in developed countries it ranges from 24% to 42%. 6

H. pylori eradication therapy based on antibiotics associated with a proton pump inhibitor is up to 80% effective, but a percentage of therapeutic failure occurs and is mainly due to resistance to antibiotics. 7 An appropriate strategy for development of therapeutic guidelines based on local bacterial resistance data is the use of culturing and an antibiogram. 7,8

The study aims to determine the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of H. pylori from patients older than 18 years who have recurrent dyspepsia.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study was carried out in two public specialty hospitals with approximately 400 beds in each in Quito, Ecuador over a period of 6 months. Patients over 18 years with symptoms of recurrent dyspepsia were selected. Those selected and who accepted signed an informed consent form and had not taken antibiotics for at least 5 days before upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Isolation and Identification of H. pylori

Two gastric biopsies were taken endoscopically: one from the fundus and one from the antrum. They were placed in a screw-cap bottle with 1 mL of sterile 0.9% saline solution and transported within two hours to the laboratory of the School of Bioanalysis of the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador (PUCE) or to the national reference laboratory of antimicrobial resistance of the National Institute of Public Health Research “Leopoldo Izquieta Pérez” (INSPI “LIP”) for analysis. 9 After maceration, they were placed on Oxoid Columbia Agar Base supplemented with 7% lamb’s blood with 10 mg/L vancomycin, 5 mg/L trimethoprim, 5 mg/L cefsulodin and 5 mg/L amphotericin B (DENT® , Oxoid UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. They were incubated in a microaerophilic atmosphere with 5% oxygen (O2), 10% carbon dioxide (CO2) and 85% nitrogen (N2) (CampyGen®, Oxoid UK) at 37 ° C for 7 days. Identification of H. pylori was done through morphological observation of the colony, gram staining (gram-negative bacilli), positive reaction for oxidase, catalase and urease tests. Isolates were stored in brain heart infusion (BHI) (Oxoid UK) with 20% glycerol at -70 ° C.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests

To reach McFarland Standard No. 3 for turbidity, a bacterial suspension was prepared from BHI broth (Oxoid UK) from a pure culture, incubated for 3 days in a microaerophilic atmosphere (CampyGen®, Oxoid UK) at 37°C. 10 Later, it was inoculated on Mueller Hinton agar (Oxoid UK) supplemented with 7% lamb’s blood. Gradient strips of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) were used for amoxicillin, metronidazole, tetracycline, levofloxacin and clarithromycin (Liofilchem, Italy) and then incubated for five days in a microaerophilic environment (CampyGen®, Oxoid UK). The cut-off points for clarithromycin were taken from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), while epidemiological cut-off points (ECV) were taken from the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) for the other antibiotics. H. pylori ATCC 43504 was used for quality control.

Ethical Issues

Prior to the study, all patients signed informed consent statements indicating the procedures that were to be carried out with the samples as well as the possible risks and benefits of participation in the study. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of each hospital and the PUCE.

Results

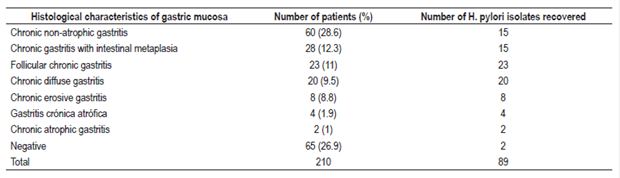

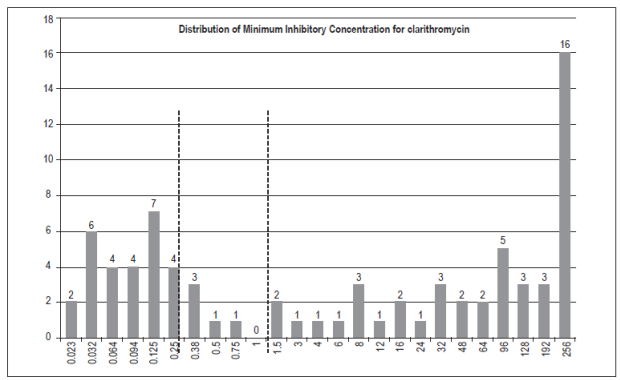

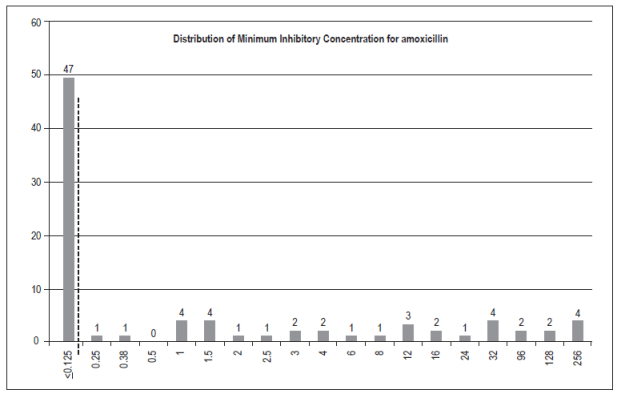

Of the 210 people involved in the study, 143 had some degree of gastric inflammation and two people had adenocarcinoma. A total of 89 (42.4%) strains of H. pylori were isolated. Of these, 87 were found to have gastric pathologies by histopathological testing (Table 1). Four strains could not be recovered for susceptibility testing: metronidazole, levofloxacin, amoxicillin and tetracycline. Seventy-eight isolates were studied for clarithromycin. (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1 Minimum Inhibitory Concentration for clarithromycin in 78 strains of H. pylori. The broken lines represent cut points according to CLSI 2017.

Figure 2 Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for amoxicillin in 83 strains of H. pylori. The dashed lines represent epidemiological cut-off points according to EUCAST 2017.

The largest number of strains that had MICs above the reference values were for metronidazole and clarithromycin, while the antibiotic association analysis for the different therapeutic schemes showed that 32% of the isolates were resistant to the combination amoxicillin/clarithromycin and 42% to clarithromycin/metronidazole (Table 2).

Discussion

H. pylori is associated with inflammatory processes in the gastrointestinal mucosa and has prevalences of around 70% to 80% worldwide, especially in developing countries. 5 In our study, H. pylori was isolated in 89 patients (42.4%), only 2 isolates were not associated with gastric inflammation, and prevalence was lower than those reported in other studies. Factors such as the difficulty of isolating H. pylori from cultures, difficulties with biopsy sites and quality, transportation and incubation conditions can influence results. 11 In our study, the biopsies obtained from the fundus and gastric antrum were selected as recommended, 12 while culturing was done within 2 hours to avoid loss of viability of bacterial strains.

Both primary resistance associated with the use of antibiotics for the treatment of infections caused by pathogens other than H. pylori and secondary resistance caused by previous H. pylori eradication treatment were considered. 13,14,15 The CLSI establishes clinical cut-off points for clarithromycin, but does not do so for amoxicillin, tetracycline, metronidazole and levofloxacin. A variation among epidemiological studies has been observed regarding cut-off points. Our study used the epidemiological cut-off points given by EUCAST and used in most European countries, but we took into account both the possibility that isolates considered to be resistant can increase as well as demonstrated poor clinical efficacy. 16

Although clarithromycin continues to be recommended as the first option for H. pylori eradication treatment, 8 our study shows that 66% of the isolates were resistant with values well above the 12% reported for Latin America, 17 and the 9.5% in Ecuador, reported in 2003 18. Raymont et al. have demonstrated clarithromycin resistant isolates from 68% of patients with a history of prior antibiotic therapy, 19 and a similar percentage of resistance has been demonstrated by Gao et al. 20

The Maastricht IV consensus on the use of macrolides recommends that local prevalence be taken into account for empirical treatment of H. pylori, and that clarithromycin’s use should be avoided when susceptibility tests show 15% to 20% of resistant strains. 8 However, since these tests are complex, few laboratories perform them. Among the mechanisms of resistance described for clarithromycin are mutations in the 23S rRNA gene and the use of proton pump inhibitors. 21,22. A deficiency of our study was that we did not investigate these mechanisms.

Our study found that 43% of the strains of amoxicillin, another first-line antibiotic in triple therapy, were resistant with MICs greater than 0.125. This is a high percentage if one takes into account that for Latin America it is between 0% and 39%, and the difference is even greater for the percentage found in Ecuador which in previous years has not exceeded 4%. 17,18 Nishizawa et al. have demonstrated that, similar to what has happened with the use of clarithromycin, after attempts to eradicate H. pylori with amoxicillin based schemes failed, the number of resistant isolates increased from 49.5% to 72%. 23 In our study, we did not obtain data on previous administration of antibiotics within or outside of eradication therapy. Nevertheless, patients with recurrent dyspepsia were selected and may have received previous antimicrobial therapy. A resistance of 63% to metronidazole is within the range reported for Latin America of 12.5% to 95% and not dissimilar to the report from Ecuador of 80.9%. 17,18

More than 30% of strains present resistance simultaneously to two antibiotics used for eradication therapy, be it clarithromycin or levofloxacin.

Previous use of antibiotics is a risk factor for increasing resistance of H. pylori strains and, consequently, for therapeutic failure, either through primary or secondary resistance. 24 A high prevalence of resistance to antibiotics used in eradication treatment was demonstrated in this study, unlike the results obtained in Ecuador in 2003. Risk-benefit analysis together with the performance of susceptibility tests is recommended whenever clarithromycin or amoxicillin is used as an empirical treatment in patients with recurrent dyspepsia or in those who may have already received previous treatment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank the staffs of the Hospital de Especialidades Eugenio Espejo and the Hospital de las Fuerzas Armadas n.° 1 in the city of Quito.

REFERENCES

1. Basso D, Zambon CF, Letley DP, Stranges A, et al. Clinical relevance of Helicobacter pylori cagA and vacA gene polymorphisms. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):91-9. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.041 [ Links ]

2. Wang F, Meng W, Wang B, et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345(2):196-202. https:// doi.org/ 10.1016/ j.canlet.2013.08.016 [ Links ]

3. Malaty HM, Kumagai T, Tanaka E, et al. Evidence from a nine-year birth cohort study in Japan of transmission pathways of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(5):1971-3. [ Links ]

4. Rocha GA, Rocha AM, Silva LD, et al. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in families of preschool-aged children from Minas Gerais, Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8(11):987-91. [ Links ]

5. Porras C, Nodora J, Sexton R, et al. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in six Latin American countries (SWOG Trial S0701). Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(2):209-15. [ Links ]

6. Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2014;19 Suppl 1:1-5. https://doi.org/10.1111/hel.12165 [ Links ]

7. Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59(8):1143-53. [ Links ]

8. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut . 2012;61(5):646-64. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084 [ Links ]

9. Ndip RN, Malange Takang AE, Ojongokpoko JE, et al. Helicobacter pylori isolates recovered from gastric biopsies of patients with gastro-duodenal pathologies in Cameroon: current status of antibiogram. Trop Med Int Health . 2008;13(6):848-54. https:// doi.org/ 10.1111/ j.1365-3156.2008.02062.x [ Links ]

10. Ogata SK, Gales AC, Kawakami E. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing for Helicobacter pylori isolates from Brazilian children and adolescents: comparing agar dilution, E-test, and disk diffusion. Braz J Microbiol. 2015;45(4):1439-48. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-83822014000400039 [ Links ]

11. Mégraud F, Lehours P. Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(2):280-322. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00033-06 [ Links ]

12. El-Zimaity H, Serra S, Szentgyorgyi E, et al. Gastric biopsies: the gap between evidence-based medicine and daily practice in the management of gastric Helicobacter pylori infection. Can J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2013;27(10):e25-30. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/897423 [ Links ]

13. Poon SK, Chang CS, Su J, et al. Primary resistance to antibiotics and its clinical impact on the efficacy of Helicobacter pylori lansoprazole-based triple therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(2):291-6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01184.x [ Links ]

14. Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Rassu M, et al. Incidence of secondary Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in treatment failures after 1-week proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapies: a prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32(8):667-72. https:// doi.org/ 10.1016/ S1590-8658(00)80327-8 [ Links ]

15. Lim SG, Park RW, Shin SJ, et al. The relationship between the failure to eradicate Helicobacter pylori and previous antibiotics use. Dig Liver Dis . 2016;48(4):385-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2015.12.001 [ Links ]

16. Alarcón T, Urruzuno P, Martínez MJ, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of 6 antimicrobial agents in Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates by using EUCAST breakpoints compared with previously used breakpoints. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35(5):278-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eimc.2016.02.010 [ Links ]

17. Camargo MC, García A, Riquelme A, et al. The problem of Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics: a systematic review in Latin America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(4):485-95. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.24 [ Links ]

18. Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Reyes G, Mulder J, et al. Characteristics of clinical Helicobacter pylori strains from Ecuador. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(1):141-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkg023 [ Links ]

19. Raymond J, Lamarque D, Kalach N, et al. High level of antimicrobial resistance in French Helicobacter pylori isolates. Helicobacter . 2010;15(1):21-7. [ Links ]

20. Gao W, Cheng H, Hu F, et al. The evolution of Helicobacter pylori antibiotics resistance over 10 years in Beijing, China. Helicobacter . 2010;15(5):460-6. [ Links ]

21. Taylor DE, Ge Z, Purych D, et al. Cloning and sequence analysis of two copies of a 23S rRNA gene from Helicobacter pylori and association of clarithromycin resistance with 23S rRNA mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41(12):2621-8. [ Links ]

22. Hirata K, Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, et al. Contribution of efflux pumps to clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25 Suppl 1:S75-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06220.x [ Links ]

23. Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Tsugawa H, et al. Enhancement of amoxicillin resistance after unsuccessful Helicobacter pylori eradication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(6):3012-4. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00188-11 [ Links ]

24. Megraud F, Coenen S, Versporten A, et al. Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe and its relationship to antibiotic consumption. Gut . 2013;62(1):34-42. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302254 [ Links ]

Received: January 26, 2017; Accepted: October 06, 2017

text in

text in