Introduction

This document presents the first case of emphysematous gastritis reported and published in Colombia. Emphysematous gastritis is a rare but deadly condition caused by gas-producing organisms that colonize the stomach wall1. There is no consensus on comprehensive management and its approach is based on experiences documented in few case reports. Possibly, the widespread lack of knowledge of this disease leads to a high rate of underdiagnosis, resulting in late interventions and an exponential increase in mortality. Early diagnosis allows for timely interventions that facilitate the approach and reduce clinical impact1,2. The latest reports seem to support conservative, non-surgical treatment in the first instance, with favorable outcomes2. The main objective of this report is to explain the clinical experience of treating a case that had never been observed in our institution and was unknown to most physicians; however, an early radiological diagnosis was made, allowing the therapy to be guided.

Clinical case

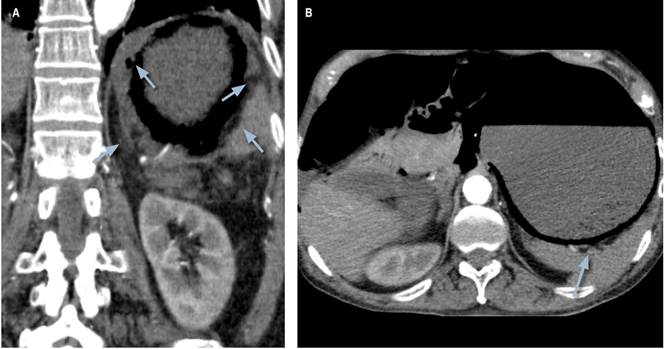

A 76-year-old male patient, with a history of advanced Alzheimer’s disease and high blood pressure, consulted after experiencing 12-hour symptoms consisting of an intense colicky abdominal pain that started in the epigastric region, irradiated to the mesogastrium, and was accompanied by unquantified fever. He denied emesis, changes in bowel movements, or other associated symptoms. During the interview, his daughter reported non-voluntary weight loss (7 kilos in about 3 months). On admission, the patient was tachycardic and febrile, with a tendency to hypotension, marked abdominal distension and generalized pain on palpation, as well as general paleness, distal coldness, and mild signs of respiratory distress. Admission blood tests were ordered, and marked leukocytosis and neutrophilia, impaired kidney function, and arterial gases were found, evidencing severe metabolic acidosis with moderate hypoxemia and hyperlactatemia (Table 1). An admission SOFA score of 6 points was established. An emergency tomography scan was requested, showing overdistended stomach with pneumatosis intestinalis, portomesenteric vein gas and gastric wall thickening with gas bubbles inside (Figure 1).

Table 1 Laboratory tests of the patient upon admission

| Laboratory tests on admission | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Value | Analysis method | Normal ranges |

| Urea nitrogen | 68 mg/dL | Kinetic UV | < 20 mg/dL |

| Serum creatinine | 1.8 mg/dL | Enzymatic colorimetric assay | 0.5 mg/dL-1.0 mg/dL |

| White blood cell count | 18.4 x 103/µL | Automated microscopy | 5.10-9.70 x 103/µL |

| Absolute neutrophil count | 17.6 x 103/µL | Automated microscopy | 1.40-6.50 x 103/µL |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | 0.9 x 103/µL | Automated microscopy | 1.20-3.40 x10 3/µL |

| HCT | 25.3% | Automated microscopy | 38.0 %-47.0 % |

| Hb | 9.1 g/d | Automated microscopy | 12- 15 g/dL |

| Platelets | 151 x 103/µL | Semiconductor laser | 150-450 x 103/µL |

| Alanine transaminase | 54 UI/L | Kinetic | 5-60 IU/L |

| AST | 26 UI/L | Kinetic | 10-34 UI/l |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 102 UI/L | Kinetic | 44-147 IU/L |

| ELISA for HIV | 0.15 UI/mL | Fourth generation ELISA | 0.0-0.9 IU/L |

| Bilirubin | 1.5 mg/dL | Colorimetry | 0.2- 1.2 mg/dL |

| Lactate | 3.6 mmol/L | Spectrophotometry | 0.1-1.5 mmol/L |

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HCT: hematocrit; Hb: hemoglobin; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

Figure 1 Enhanced CT scan of the abdomen. Overdistended stomach and findings compatible with infiltration of gas into the stomach walls. Gas bubbles in the stomach wall (arrow).

In view of the suspicion of emphysematous gastritis, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam and metronidazole was started. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and resuscitation maneuvers, fluid therapy and the antibiotic coverage previously described were initiated. Approximately 48 hours after admission, the patient’s condition deteriorated progressively, and signs of peritoneal irritation and hemodynamic instability were observed. A few minutes after showing signs of peritoneal irritation, he was taken to emergency laparotomy with findings of necrosis of the gastric wall and four quadrant purulent peritonitis. A total gastrectomy was performed with Roux-en-Y anastomosis and peritoneal washing. The patient was transferred from the surgical room to the ICU with vasopressor support and invasive mechanical ventilation. His hemodynamic parameters forced an infusion of noradrenaline and vasopressin. Within a few hours, due to refractory hypotension, the patient required the initiation of dobutamine and the antibiotic escalation to carbapenem and glycopeptide.

A follow-up complete blood count showed persistent leukocytosis and neutrophilia, worsening of kidney function, and no lactate clearance (Table 2). After initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, the patient had a period of stability of approximately 72 hours, but 4 days after laparotomy, the patient presented with cardiorespiratory arrest. Although asystole rhythm was documented, after 20 minutes of resuscitation maneuvers, he was declared dead. The histopathological report documented numerous bacterial colonies of Clostridium sp. within the submucosa, emphysematous gastritis, and lesion compatible with infiltrating adenocarcinoma of the gastric mucosa.

Table 2 Postoperative laboratory tests performed during the patient’s stay in the ICU

| Laboratory tests in ICU | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Values | Analysis method | Normal ranges |

| Urea nitrogen | 76 mg/dL | Kinetic UV | < 20 mg/dL |

| Serum creatinine | 2.7 mg/dL | Enzymatic colorimetric assay | 0.5 mg/dL-1.0 mg/dL |

| White blood cell count | 21.3 x103/µL | Automated microscopy | 5.10-9.70 x 103/µL |

| Absolute neutrophils | 20.2 x103/µL | Automated microscopy | 1.40-6.50 x 103/µL |

| Absolute lymphocytes | 0.6 x 103/µL | Automated microscopy | 1.20-3.40 x 103/µL |

| HCT | 18.2% | Automated microscopy | 38.0- 47.0 % |

| Hb | 7.1 g/d | Automated microscopy | 12- 15 g/dL |

| Platelets | 80 x 103/µL | Semiconductor laser | 150-450 x 103/µL |

| Bilirubin | 2.1 mg/dL | Colorimetry | 0.2- 1.2 mg/dL |

| Lactate | 5.5 mmol/L | Spectrophotometry | 0.1-1.5 mmol/L |

Discussion

Emphysematous gastritis is a rare infection caused by the invasion of gas-producing bacteria into the gastric wall that results in suppurative inflammation with progressive involvement of the deep layers, abscess formation and subsequent necrosis3. It is a disease with high mortality due to the non-specific nature of symptoms and signs, which causes delays in diagnosis and timely therapy3. Few cases are published in the literature and there is a wide lack of knowledge of the nature of the disease. The pathophysiology of emphysematous gastritis has not been established yet1,4, but it is considered that mucosal lesions allow the penetration of microorganisms into the deepest layers of the wall4. It has also been suggested that it may be secondary to hematogenous dissemination from a distant focus4. Symptoms are non-specific and include a wide range of manifestations such as abdominal pain predominantly in the epigastric region, nausea, emesis, and diarrhea4,5. Some authors have established passage of necrotic tissue with emesis, in the shape of the gastric wall, secondary to dissection of the muscularis mucosa as a pathognomonic sign5. At the time of diagnosis, patients usually present with signs of inflammatory response such as fever and leukocytosis or even with hemodynamic instability5.

Therefore, at this point it is necessary to make a distinction between gastric emphysema and emphysematous gastritis since these two conditions are easily confused and, in most cases, are considered the same, although their clinical behavior is diametrically opposed. Systematic literature reviews have made it possible to elucidate and characterize each condition more or less accurately. Matsushima et al. carried out an interesting review of 73 cases in which they achieved a clear distinction that allowed establishing criteria to facilitate the differentiation between both conditions when approaching a patient with symptoms and radiological findings of gas within the stomach wall6.

In the one hand, gastric emphysema is a scenario in which gas accumulation in the stomach wall is identified. It occurs as a result of air entering the interior of the wall, secondary to disruption of gastric mucosal barrier6. This condition is more associated with direct mechanical mucosal lesions or with tears due to increased intraluminal pressures7. 41% of gastric emphysema cases are related to underlying gastric neoplasms6 and once mucosal damage is corrected or treated, the prognosis of gastric emphysema is usually favorable6,7. Gastric emphysema can result in abdominal pain of different intensities that are often accompanied by nausea and emesis, and, in most cases, symptoms resolve without the need for clinical intervention. There are even asymptomatic patients whose diagnosis is incidental and the result of the study of other conditions such as gastric tumors.

In contrast, the 41 cases reported in the English literature of emphysematous gastritis demonstrate that this condition is the product of the invasion of gas-producing microorganisms into the gastric wall and is not necessarily related to alterations in mucosal integrity6,8. The literature review conducted by Watson et al. in 2016 established that the causative microorganisms have not been identified in almost half of the reported cases, but several germs were isolated in 20 % -which is why they were considered of polymicrobial etiology-, and bacteria of the Clostridium species were found in 6 %8. In the remaining cases, multiple species of bacteria were found, as well as parasites such as Strongyloides stercoralis, and fungi such as Candida and Mucor6,7. Possible predisposing factors have been identified, including alcohol consumption, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, and lymphoma8,9.

Some authors have described imaging differences between gastric emphysema and emphysematous gastritis. It has been described that the most important tomographic finding in gastric emphysema consists of linear bands of air that follow the arrangement of the layers of the gastric wall. In gastric emphysema, there is usually no mucosal thickening10. Even though there is no gold standard for the diagnosis of emphysematous gastritis, it has been proposed that clinical suspicion in combination with abdominal x-ray is sufficient to guide a diagnosis8. However, the widespread lack of knowledge of the disease could result in this combination not being sufficient to support a close diagnosis. Abdominal tomography has greater sensitivity and specificity for the detection of intramural bowel gas2. Imaging findings in CT scans of patients with emphysematous gastritis include air cysts that infiltrating the stomach wall, pneumoperitoneum, and accumulation of gas in the portal vein and its branches4,8. Thickening of the stomach wall with submucosal edema and intramural abscesses are also described8,11. Intestinal pneumatosis and pneumoperitoneum are more common in emphysematous gastritis than in gastric emphysema10.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy has been performed in approximately 45% of the reported cases of patients with evidence of air in the gastric wall6. More than half of all cases of emphysematous gastritis that have undergone endoscopy show necrosis of the stomach wall6,10. In addition, areas of erythema and edema with friable mucosa or ulcerated areas with fibrinopurulent exudate have been described12. No findings of necrosis or purulent exudate have been reported in gastric emphysema, but it is common to find erythema and edema with no other alterations. In emphysematous gastritis, histopathology reports show mucosal thickening with leukocyte infiltration and vascular thrombosis13, and sometimes the microorganism causing the condition12.

Regarding the treatment of emphysematous gastritis, the reviews have shown that immediate surgery does not seem to be the best choice as the first line of treatment, and it should be considered in patients with perforation and ischemia14,15. Some case reports have shown the effectiveness of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy associated with supportive therapies such as fluid resuscitation7,8. According to the studies, surgery does not confer additional benefits and does not guarantee better survival outcomes8. When caused by multiple types of microorganisms, emphysematous gastritis should be treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, if possible conjugated, and should consider the prevalence of the main microorganisms described in the different case reports8,15,16. Surgery is reserved for cases in which the patient presents with signs of peritoneal irritation, hemodynamic instability, septic shock, or other findings suggestive of gastric perforation and subsequent peritonitis13.

For cases in which differentiation between gastric emphysema and emphysematous gastritis is not achieved, Matsushima et al. proposed an approach algorithm for patients with clinical findings and radiological findings of air in the gastric wall6. When approaching a patient with abdominal pain and intramural gas findings, Matsushima et al. proposed the initiation of fluid therapy, broad-spectrum antibiotics, nasogastric tube decompression and oral route restriction6. If diagnostic doubts persist, endoscopy of the upper digestive tract is suggested6. If ischemia or necrosis of the stomach wall are visualized, laparotomy is most convenient6.

text in

text in