Introduction

In the early 1990s, two case series described adult patients suffering from dysphagia histologically associated with esophageal infiltration by more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/HPF)1,2, while control group patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) had an average of 3.3 eos/HPF. This pattern was quickly recognized as a distinct entity from GERD and was described as primary or idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). The presentation of dysphagia and food impaction in atopic individuals, with endoscopic findings of esophageal rings and longitudinal furrows, was markedly different from the heartburn, regurgitation, and erosive esophagitis seen in GERD. A few months later, Kelly and colleagues3 reported a series of allergic children presenting with GERD-like symptoms such as anorexia, vomiting, and failure to thrive, who were refractory to medical or surgical therapy. These pediatric patients demonstrated significant eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus and responded to treatment with a hypoallergenic diet. In addition to coinciding with the increased use of endoscopy in children, it was recognized that esophageal biopsies could show inflammation even when the mucosa appeared normal endoscopically4. This observation led to the adoption of mucosal biopsies as a standard practice in children undergoing endoscopic evaluation for symptoms, a key difference from endoscopic practices in adults.

Additionally, Kelly’s publication3 laid the groundwork for a series of future studies examining the allergic diathesis and mechanisms of EoE. Therapeutic regimens were developed, including the elimination of the six most common food allergens and the implementation of a diet guided by food allergy testing5,6. Furthermore, the global concept emerged that EoE was a chronic disease, as patients experienced recurrence of symptoms when foods were reintroduced into their diet.

Due to the challenges of adhering to dietary restrictions and the impact of steroids on other eosinophilic diseases, researchers opted for two alternative therapies. In 1998, Faubion and colleagues7 adapted a novel approach to deliver topical steroids to the esophageal mucosa. They utilized aerosolized steroids from an asthma inhaler, administered via ingestion to the esophageal mucosa, eliciting an anti-inflammatory response. In their series of four patients, they found this delivery method to be effective in alleviating symptoms and reducing esophageal eosinophilia upon examination. That same year, Liacouras and colleagues8 demonstrated that patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) responded clinically and histologically to prednisone, although symptoms recurred when the medication was discontinued.

In the absence of secondary causes of esophageal eosinophilia, such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, celiac disease, hypereosinophilic syndrome, or Crohn’s disease, among others, EoE is a chronic, localized, and progressive disorder mediated by the type 2 T-helper immune response. It is characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophil-predominant inflammation. Over the past 20 years, the incidence and prevalence of EoE have increased significantly9-11, including in our region12,13, raising the question of whether the disease manifests similarly in children and adults. Children with EoE exhibit clinical and endoscopic features distinct from those seen in adults, which may explain some differences in symptom presentation.

Using esophageal biopsies from adult and adolescent patients diagnosed with eosinophilic esophagitis at three referral centers, the aim was to compare clinical characteristics, diagnostic delays (defined as the time elapsed between symptom onset and biopsy-confirmed diagnosis), endoscopic and histologic findings, allergenic comorbidities, and therapeutic options employed in adolescents (<18 years) versus adults (≥18 years) with EoE.

Patients and methods

This is a cross-sectional analysis based on the results of esophageal biopsies diagnosing EoE obtained over seven years (from January 2015 to December 2021) at four institutions in Medellín, Colombia. This diagnosis allowed for telephone or in-person contact with patients, and two age groups were considered in the evaluation: those under 18 years old (adolescents) and those 18 years or older (adults).

Analyzed Variables

The data collected include sex, date and age at diagnosis, endoscopic characteristics, the EoE phenotype (inflammatory, structuring, or mixed), the maximum eosinophil count at diagnosis, and the presence of concomitant atopic manifestations (persistent or seasonal), as determined at the time of EoE diagnosis. Additionally, the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), dietary modifications, and therapies with swallowed topical steroids were considered, along with an evaluation of the response to therapy (both clinical and histological). Finally, the need for endoscopic dilation and the number of dilation sessions were assessed.

Definition of Terms

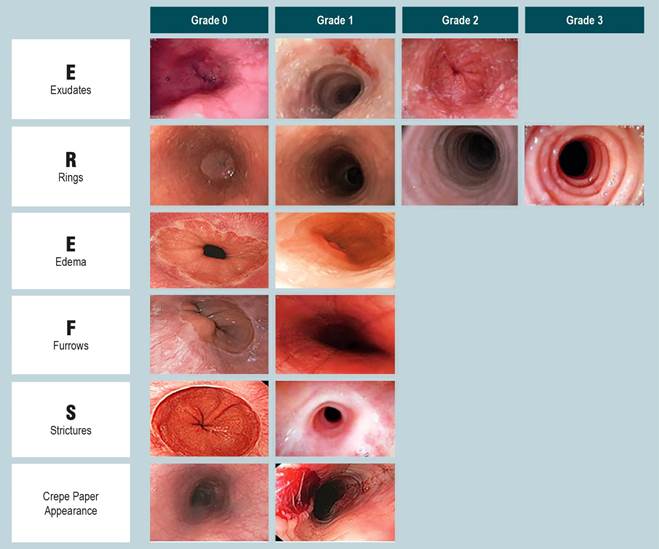

Based on the endoscopic report, EoE characteristics were recorded according to the EREFS classification system14. The total EREFS score (0-9) is calculated by summing the severity scores of five main individual components (edema: 0-1, rings: 0-3, exudates: 0-2, furrows: 0-1, and strictures: 0-1) and the minor finding of crepe paper esophagus (mucosal fragility or laceration upon endoscope passage: 0-1). Higher scores indicate more severe endoscopic findings. There are two phenotypic forms of the disease: an inflammatory form and a fibrostenotic form. A normal esophageal diameter, whitish exudates, edema, and linear furrows constitute the inflammatory form, while fixed rings, strictures, and esophageal narrowing characterize the fibrostenotic type. Given that ongoing eosinophilic inflammation tends to progress to fibrous remodeling with collagen deposition and stricture formation, a proportion of patients present with mixed endoscopic features of these two phenotypes.

Treatment response is independently evaluated based on clinical, endoscopic, and histological criteria. Symptomatic improvement of >50% from baseline is considered a clinical response. Histological remission is defined as a maximum eosinophil count below the diagnostic threshold of 15 cells per high-power field (HPF) across all esophageal levels after treatment.

Treatment

The therapy evaluated reflects real-world experience in managing EoE. First-line anti-inflammatory therapies are selected based on patient characteristics and preferences. Endoscopic dilation is performed in cases of esophageal strictures (either at the time of disease diagnosis or in combination with effective anti-inflammatory treatment), narrow-caliber esophagus, or persistent symptoms despite histological and endoscopic remission.

Statistical Analysis

The mean, median, standard deviation (SD), and interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated for continuous variables. The mean and SD were used for variables with a normal distribution, while the median and IQR were applied to those with a non-normal distribution. Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Comparisons were performed using the Student’s T test for normally distributed variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Percentages were calculated for categorical variables, which were compared between groups using the chi-square (χ2) or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a p-value <0.05.

Ethical Considerations

The research involving human participants was conducted in compliance with fundamental human rights and ethical principles for biomedical research involving humans, in accordance with Article 11 (right to life) of the Political Constitution of Colombia and the agreement of the World Medical Association. Additionally, the study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Law 23 of 1981, and Resolution 8430 of 1993. The study was carried out in conformity with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP).

Institutional ethics committees from each participating entity approved the study protocol. In accordance with the ethical risk classification outlined in Colombia’s Resolution 8430/93, this study was considered to be risk-free, as it involved the use of retrospective documentary research methods and techniques. There were no intentional interventions or modifications to the biological, physiological, psychological, or social variables of the individuals participating in the study. The research consisted of reviewing medical records, conducting interviews, completing questionnaires, and other methods where no sensitive aspects of participants’ behavior were identified or addressed.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Patients were contacted following the histological confirmation of EoE, and data on birth dates and diagnosis dates were recorded. The adult cohort (≥18 years at diagnosis) consisted of 272 patients (81.4%), while the adolescent cohort (<18 years at diagnosis) included 62 patients (18.6%). No sex differences were observed between adults and adolescents, with males predominating in all age groups (75.8% in adolescents and 72.1% in adults; p = 0.659). The main demographic and clinical characteristics of these patient cohorts are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1 Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, Atopic Comorbidities, Endoscopic Phenotype, Eosinophil Count at Diagnosis, and Therapies in Adult and Pediatric EoE Patients

| Adolescents n = 62 (%) | Adults n = 272 (%) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): median ± SD | 14 ± 1.6 | 33 ± 8.8 | ||

| Sex M:F | 47:15 | 196:76 | 0.659 | |

| Diagnosis delay (months ± SD) | 12 ± 2.9 | 22 ± 6.4 | 0.001 | |

| Allergies | No | 33 (53.2) | 169 (62.1) | 0.195 |

| Rhinitis | 8 (12.9) | 32 (11.8) | 0.572 | |

| Conjunctivitis | 5 (8.1) | 21 (7.7) | 0.709 | |

| Dermatitis | 7 (11.3) | 17 (6.2) | 0.119 | |

| Asthma | 9 (14.5) | 33 (12.1) | 0.426 | |

| Phenotype | Inflammatory | 51 (82.2) | 188 (69.1) | 0.03 |

| Stenotic | 4 (6.5) | 46 (16.9) | 0.02 | |

| Mixed | 7 (11.3) | 38 (14.0) | 0.33 | |

| Eosinophil count (median ± SD) | 47 ± 15.7 | 35 ± 14.1 | 0.017 | |

| Treatment | Dietary | 52 (83.8) | 115 (42.3) | <0.01 |

| Oral steroids | 48 (77.4) | 137 (50.3) | <0.01 | |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 34 (54.8) | 248 (91.2) | <0.01 | |

| Dilations | 1 (1.6) | 26 (9.6) | 0.038 | |

SD: Standard Deviation. Author’s own research.

Diagnosis Delay

The median diagnostic delay for EoE was 17.1 ± 5.5 months, significantly longer in adults compared to adolescents (22 ± 6.4 months versus 12 ± 2.9 months; p = 0.001).

Allergic Manifestations

Rhinitis, asthma, conjunctivitis, and dermatitis were the four main atopic conditions reported by patients. However, no significant differences were observed between the adolescent and adult populations (Table 1).

Endoscopic Evaluation

The EREFS scores for endoscopic activity are presented in Figure 1 and Table 2. Pediatric patients predominantly exhibited higher mean scores for inflammatory features (edema, furrows, exudates, and friability) compared to the fibrotic components of the EREFS (rings or strictures), which were more prevalent among adults. This contributed to a significantly higher prevalence of stenotic phenotypes in adults (11.8% versus 4.8%) compared to adolescents at the time of EoE diagnosis (p < 0.048).

Figure 1 Endoscopic Characteristics of EREFS Scores in the Evaluation of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Author’s own research.

Table 2 Endoscopic Characteristics of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Both Groups

| Adolescents n = 62 (%) | Adults n = 272 (%) | Total n = 334 | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Findings | Abnormal | 59 (95.2) | 232 (90.1) | 291 (87.1) | 0.036 | |

| Normal | 3 (4.8) | 40 (9.9) | 43 (12.9) | |||

| EREFS score | Exudate | 0 | 13 (21.0) | 99 (36.4) | 112 (33.6) | 0.021 |

| 1 | 17 (27.4) | 80 (29.4) | 97 (29.0) | |||

| 2 | 32 (51.6) | 93 (34.2) | 125 (37.4) | |||

| Rings | 0 | 20 (32.3) | 153 (56.3) | 173 (51.8) | 0.002 | |

| 1 | 6 (9.7) | 20 (7.4) | 26 (7.8) | |||

| 2 | 15 (24.1) | 55 (20.1) | 70 (21.0) | |||

| 3 | 21 (33.9) | 44 (16.2) | 65 (19.4) | |||

| Edema | 0 | 11 (17.7) | 105 (38.6) | 116 (34.7) | 0.002 | |

| 1 | 51 (82.3) | 167 (61.4) | 218 (65.3) | |||

| Furrows | 0 | 10 (16.1) | 82 (30.1) | 92 (27.6) | 0.026 | |

| 1 | 52 (83.9) | 190 (69.9) | 242 (72.5) | |||

| Stricture | 0 | 59 (95.2) | 234 (88.2) | 293 (87.7) | 0.048 | |

| 1 | 3 (4.8) | 38 (11.8) | 41 (12.3) | |||

| Friability | 0 | 29 (46.8) | 187 (68.8) | 216 (64.7) | 0.082 | |

| 1 | 33 (53.2) | 85 (31.2) | 118 (35.3) | |||

Author’s own research.

Eosinophil Count

Differences in peak eosinophil count per high-power field (HPF) were also assessed. Pediatric patients exhibited higher maximum eosinophil densities, with median counts in esophageal biopsies significantly exceeding those of adults (47 ± 15.7 versus 35 ± 14.1, p = 0.017). Correspondingly, the increased percentage of stenotic phenotypes with advancing patient age was inversely correlated with peak eosinophil counts in esophageal biopsies (Spearman’s Rho = -0.161; p < 0.003).

Choice of First-Line Treatment and Efficacy in Inducing Remission

Differences were observed in the choice of first-line treatment for children and adults with EoE in real-world practice (Table 1). Dietary therapies (83.8% versus 42.3%) and oral steroids (77.4% versus 50.3%, p < 0.01) were used more frequently in children than in adults. A trend was noted where the use of dietary therapies as an initial intervention to induce EoE remission decreased with patient age at diagnosis, while the opposite was observed for proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. The efficacy of the three first-line treatment options in inducing clinical and histological responses was not different between children and adults (Table 1). Additionally, no differences in efficacy were detected among empirical food elimination diets, PPIs, and oral steroids between pediatric and adult patients. Finally, endoscopic dilations performed in children and adults (either as a standalone procedure or combined with other anti-inflammatory treatments) were analyzed. This procedure was performed more frequently in adults (38 patients, 11.8%) than in children (3 patients, 4.8%; p = 0.048).

Discussion

Based on biopsy findings, this study compiles the various characteristics and differences in EoE presentation between adolescents and adults. Differences between adolescent-onset EoE and adult-onset EoE were evaluated with respect to symptoms, endoscopic findings, histological activity at diagnosis, and the use of different treatment options. Data collection enabled direct comparisons between patients of different age groups to better define the natural history of EoE and its features across age ranges. The symptoms associated with EoE and its endoscopic characteristics evolved across age groups, with notable differences even within specific age ranges. As described recently, the presentation of EoE is heterogeneous in the pediatric population, with findings varying between young children and adolescents15. Fibrotic features progressively develop with age, leading to a significantly higher risk of strictures and the need for endoscopic dilation in adults. Differences were noted in the first-line treatments administered to pediatric versus adult EoE patients, though the response to these treatments was similar regardless of age16.

In a recent review, Visaggi and colleagues17 analyzed the key differences between children and adults with EoE at the time of diagnosis, providing indirect evidence that endoscopy in children often reveals a predominantly inflammatory pattern, while adults more frequently exhibit a fibrostenotic phenotype. A recent study based on data from the European Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis Registry also found that endoscopic findings of fibrosis, particularly esophageal rings, were more common in adolescents, whereas exudates were more frequent in younger children15. Similarly, a retrospective cohort of EoE patients recruited from 10 centers in the United States documented that a higher proportion of pediatric EoE patients displayed an inflammatory phenotype on endoscopy, while older individuals exhibited a more fibrostenotic phenotype compared to pediatric patients18. This difference is clearly supported by our study, which found that a fibrostenotic phenotype was nearly three times more prevalent in adults than in children. This finding may be related to a longer subclinical disease course in adults and a more extended diagnostic delay from symptom onset. Delayed diagnosis exceeding two years in EoE patients has recently been associated with increased disease activity and progression to fibrostenosis19. Untreated EoE has been linked to esophageal stricture formation, with the risk of a fibrostenotic phenotype doubling for every 10-year increase in age, indicating that EoE is a progressive disease20.

The disease phenotype may also influence symptom presentation. Most children reportedly experience nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, growth delay, and epigastric burning15,17,21,22. In contrast, dysphagia and food impaction are considered hallmark symptoms of adult-onset EoE, as previously documented18.

Population-based epidemiological studies have described that the vast majority of EoE patients are between the first and sixth decades of life23, although cases have been reported across all ages24. However, the incidence of EoE decreases with increasing age, and studies focusing on elderly patients are scarce25. Given that this age group is frequently excluded from clinical trials evaluating new EoE therapies, their response to different treatments remains largely unknown. A recent retrospective cohort study identified only 12 patients over 65 years old among newly diagnosed individuals treated with oral steroids in the University of North Carolina EoE database26.

Although environmental factors are increasingly recognized as significant in the etiology of EoE27, familial clustering of EoE in population-based studies suggests a substantial genetic contribution28. Our study also evaluated the presence of four atopic conditions associated with EoE-rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, atopic dermatitis, and asthma-and found no differences between children and adults. A prior observation by Vernon and colleagues similarly described comparable histories of allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, immunoglobulin E-mediated food allergies, and familial atopy in both children and adults with EoE29, noting only a higher prevalence of asthma in children compared to adults.

In our study, similar to other survey-based studies conducted in Europe30,31, the United States32, and Australia33 regarding therapy, PPIs were the most commonly prescribed first-line therapy for EoE across all age groups. This finding is consistent with records of clinical practice34. However, PPIs were prescribed significantly less frequently in adolescents compared to adults. For adolescents, dietary therapy and steroids represented first-line management, while PPIs and steroids were predominant in adults (p < 0.01). Notably, the effectiveness of different therapies did not differ between the age groups. Regarding endoscopic dilation, it was used six times more frequently in adults than in children, reflecting the higher prevalence of fibrostenotic EoE among adults. However, the number of dilation procedures performed did not differ by patient age, likely indicating the dominant effect of endoscopic dilation when combined with effective anti-inflammatory treatment for EoE35,36.

Another significant finding of our study was the markedly shorter diagnostic delay among pediatric patients compared to adults (12 ± 2.9 vs. 22 ± 6.4 months; p = 0.001). Differences in diagnostic delays from symptom onset were previously reported in a 2012 multicenter study in Spain, which found delays of 28.04 ± 30 months for children and 54.7 ± 62 months for adults37. Data from the European EoE Registry indicate a diagnostic delay of approximately 1 year for pediatric EoE patients overall, closely matching the results of the European Registry of Clinical, Environmental, and Genetic Determinants in Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EoE CONNECT). However, these figures come from specialized centers managing EoE patients. Overall, diagnostic delays in EoE remain unacceptably long, particularly among adult patients38.

Our study has several limitations. First, due to its retrospective nature, some data-such as details on dietary modifications or steroid medications-could not be reliably collected, limiting the evaluation of therapies in both groups. Second, as multiple centers contributed patients, there may be some heterogeneity in the treatment approaches for EoE patients, and differences in practice patterns could have influenced the treatment of both pediatric and adult cohorts. Third, this may have had a significant impact, as most treating physicians were not EoE experts and did not work in specialized EoE referral centers. Fourth, our data could not evaluate EoE disease endotypes, i.e., subtypes defined by molecular and cellular markers that may influence the identification, prognosis, and treatment response in EoE patients.

In conclusion, the largest study cohort comparing adolescent-onset and adult-onset EoE reveals that patients diagnosed at younger ages exhibit distinct clinical and endoscopic characteristics and differences in first-line therapy usage. However, treatment response rates were similar across all age groups.

text in

text in