Introduction

Constipation is defined as difficulty in passing stools, often requiring straining, effort, or even the use of manual maneuvers or laxatives, leading to additional symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and irritability. It also encompasses changes in stool frequency, which may vary across age groups. For instance, in children older than three years, one bowel movement per day is considered normal; in children aged 1 to 3 years, the average is 1.8 bowel movements per day; for infants aged 6 to 12 months, it is two per day; and for infants aged 0 to 3 months, the average is three bowel movements daily1-3.

Chronic constipation negatively impacts the quality of life in children and is a frequent cause of medical consultations4. Globally, the prevalence of constipation in the pediatric population ranges from 0.5% to 32.2% (with an average of 9.5%), with higher rates observed in females1,2. A study by Saps and colleagues reported a prevalence of 12% to 19% among school-aged Colombian children5. The etiology of constipation is multifactorial, encompassing nutritional, psychological, and colorectal anatomical factors, as well as systemic metabolic, endocrine, neurological, medication-related, and motility or brain-gut axis disorders3,6.

When patients fail to respond to treatments based on clinical history, chronic intractable or refractory constipation should be considered. While the distinction between intractable and refractory constipation is not universally defined, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) defines refractory constipation as constipation unresponsive to optimal conventional treatment for at least three months7. Some reviews, however, characterize refractory constipation as persisting for at least three months despite maximum doses of laxatives and requiring daily rectal stimulation, enemas, or suppositories8. In such cases, anorectal physiological tests, such as high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRARM), are indicated9. This diagnostic test evaluates the neuromuscular function of the anorectal complex1,10. The conventional interpretation of HRARM findings classifies anorectal dysfunctions into categories such as internal or external sphincter disorders, rectal sensation abnormalities, dyssynergic defecation, absence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR), and abnormal balloon expulsion11,12.

The primary indications for performing anorectal manometry in pediatrics are suspected Hirschsprung’s disease, constipation persisting despite adequate treatment, evaluation of patients with fecal incontinence, and postoperative assessment following corrective surgery for anorectal malformations13,14.

A review of normal values for high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRARM) by age in pediatrics reveals that existing studies include few patients with diverse demographic characteristics, and no global consensus has yet been established to define reference values for the interpretation of manometry in children. In the Polish study by Banasiuk, the following reference values were reported: the mean resting sphincter pressure was 83 ± 23 mm Hg, contraction pressure was 191 ± 64 mm Hg, the mean anal canal length was 2.62 ± 0.68 cm, and the volumes for first sensation, urgency, and discomfort were 25 mL, 45 mL, and 90 mL, respectively15.

The International Anorectal Physiology Working Group (IAPWG) published the London Classification consensus16 on the terminology and interpretation of HRARM in adults. This consensus provides an objective and accurate framework for diagnosing anorectal disorders, classifying anorectal dysfunction into four groups: anal tone and contractility disorders, rectoanal coordination disorders, rectal sensation disorders, and absence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR)11,16.

There is limited information regarding the prevalence of anorectal disorders in the pediatric population in South America, and HRARM is not routinely performed in children with constipation due to the lack of standardized methodology and reference values for its interpretation10. For these reasons, this study aims to describe the manometric characteristics of anorectal disorders in children with refractory constipation using conventional nomenclature and proposes the development of a classification system similar to the London Classification for pediatric patients.

Materials and methods

This was a descriptive, observational, cross-sectional data exploration study involving patients under 18 years of age diagnosed with chronic refractory constipation who underwent high-resolution anorectal manometry (HRARM) at the gastrointestinal physiology unit of Hospital Universitario San Ignacio (HUSI), Colombia, between 2014 and 2018. The HRARM was performed using a high-resolution ManoScan™ 360 system (Given Imaging®). Patients with non-retentive fecal incontinence, chromosomal abnormalities, congenital anomalies, anal sphincter reconstruction, growth disorders, or neurodevelopmental disorders were excluded. The manometry procedures were performed by a trained nurse and interpreted by gastroenterologists. Patients were prepared with a phosphate rectal enema and underwent the procedure while fasting, in a left lateral decubitus supine position. A rectal catheter with five radial sensors spaced one centimeter apart and a proximal balloon was inserted. Five minutes later, the following parameters were measured: resting anal pressure, voluntary contraction, defecation maneuver, rectal evacuation sensation, rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR), and, finally, a balloon expulsion test (BET). For patients under four years of age and some older children, HRARM was conducted under sedation, evaluating basal anal sphincter pressure and RAIR presence. All studies were re-interpreted by a pediatric resident and a pediatric gastroenterologist. In cases with discrepancies in initial readings, the unit’s entire physiology group reviewed the studies to reach a diagnostic consensus.

Demographic and manometric variables were recorded in an MS Excel database. The ethics committee of HUSI approved the study, which was classified as risk-free according to Article 11 of Resolution 8430 of 1993, issued by the Ministry of Health in Colombia. Informed consent, obtained from the children’s guardians, included authorization for the academic and research use of the results, ensuring adherence to ethical principles and complete confidentiality of patient identities.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were described using measures of central tendency and dispersion, while frequencies and percentages were calculated for qualitative variables. For group comparisons, Student’s T test was applied for continuous variables, and the chi-square test was used for categorical qualitative variables. For comparisons of means, Student’s T test was used for samples with fewer than 30 observations, while the Z test was employed for larger samples. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for group comparisons.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The study included 110 HRARM procedures performed during the study period. Six studies were excluded due to incomplete records, one due to evaluation following colostomy closure, and 14 due to a diagnosis of fecal incontinence. Ultimately, 89 manometry procedures met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Among the patients, 72% had Bristol stool scale types 1 and 2, 80% had bowel movements less frequently than every three days, and 25% had bowel movements as infrequently as once per week.

Table 1 Demographic Distribution of Pediatric Patients with Chronic Constipation

| Variable | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 10 years (SD: 5) | ||

| Male | 46 (51.6%) | ||

| Bristol stool scale (n = 51) |

|

|

|

| Bowel movement frequency (n = 51) |

|

|

|

| Mean resting ARS pressure | 63.6 mm Hg (SD: 31.6) | ||

| ARS length | 2.0 cm (SD: 1.1) | ||

| Mean balloon volume triggering RAIR | 40 mL | ||

| Max pressure during squeeze | 173.8 mm Hg (SD: 59.7) | ||

| Patients without significant relaxation during push (n = 57) | 19 (33%) | ||

| Mean volume for first defecatory sensation | 100 mL | ||

| Mean volume for first discomfort | 150 mL | ||

| Mean volume for urgency | 200 mL | ||

SD: Standard Deviation; ARS: Anorectal Sphincter; RAIR: Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex. Source: Author’s own research.

The mean resting anal sphincter pressure was 63.6 mm Hg, while the mean maximum anal pressure during squeeze was 173.1 mm Hg. Among the patients, 33% failed to achieve significant anal sphincter relaxation, and the mean volumes required to trigger first sensation, discomfort, and urgency exceeded 100 mL. Eight percent of the patients lacked RAIR. The balloon expulsion test (BET) was conducted in 56 patients, with abnormal results observed in 80% of cases.

No significant differences were observed in manometric parameters by sex; however, some differences were noted between age groups. In children under five years, the mean resting anal sphincter pressure was one-third lower than that of children older than five years (46.9 versus 69.5 mm Hg). The anal sphincter length was 30% shorter in children under nine years (1.48 versus 2.15 cm). Among children under 12 years, the mean volume required to elicit the first defecatory sensation was 32% lower (83 versus 122 mL), the volume required to generate discomfort was 30% lower (144.3 versus 205.1 mL), and the volume required to induce urgency was 34% lower (191.3 versus 253.3 mL) (Table 2).

Table 2 Distribution of Manometric Parameters by Age Groups and Sex

| Manometric Parameters | All Ages | n | Males (53%) | n | Females (47%) | n | <5 Years | n | 5 a 8 Years | n | 9 a 12 Years | n | >12 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 10 años (SD: 5) | 46 | 9.34 (SD: 4.9) | 43 | 11.12 (SD: 4.7) | 15 | 2.5 (SD: 1.2) | 15 | 6.8 (SD: 0.9) | 28 | 10.3 (SD: 1.1) | 31 | 15.6 (SD: 1.4) |

| Mean resting ARS pressure (mm Hg) | 63.6 (SD: 31.6) | 46 | 62.1 (SD: 24.9) | 43 | 69.6 (SD: 38.8) | 15 | 46.9** (SD: 18.1) | 15 | 65.8 (SD: 34.6) | 28 | 72.7 (SD: 41.9) | 31 | 68.4 (SD: 23.7) |

| ARS length (cm) | 2.0 SD (SD: 1.1) | 46 | 1.9 (SD: 1.0) | 43 | 1.9 (SD: 1.3) | 15 | 1.4** (SD: 0.7) | 15 | 1.5** (SD: 1.0) | 28 | 2.0 (SD: 1.2) | 31 | 2.3 (SD: 1.3) |

| Mean balloon volume triggering RAIR (mL) | 20 | 46 | 29.6 | 41 | 31.7 | 15 | 28.1 | 15 | 25.3 (SD: 14.1) | 27 | 31.9 (SD: 20.2) | 30 | 33.3 (SD: 18.4) |

| Max pressure during squeeze (mm Hg) | 173.8 (SD: 59.7) | 25 | 189 (SD: 52) | 32 | 167.9 (SD: 59.1) | 1 | 232 | 6 | 181.1 (SD: 61.4) | 22 | 177.1 (SD: 63.4) | 28 | 174.2 (SD: 52.6) |

| Percentage relaxation during push (%) | 28.3 (SD: 18.6) | 23 | 22.7 (SD: 19.7) | 32 | 30.8 (SD: 16.4) | 1 | 26 | 5 | 19.4 (SD: 24.4) | 21 | 27.5 (SD: 16.1) | 28 | 28.8 (SD: 19.1) |

| Mean volume for first defecatory sensation (mL) | 100 | 23 | 115.62 (SD: 77) | 32 | 98.8 (SD: 60.7) | 1 | 60 | 6 | 81.7 (SD: 39.2) | 20 | 88 (SD: 57.5) | 28 | 122** (SD: 76) |

| Mean volume for first discomfort (mL) | 150 | 23 | 188.26 (SD: 96.0) | 31 | 172.6 (SD: 79.5) | 1 | 80 | 6 | 118.3 (SD: 41.7) | 20 | 161.5 (SD: 63.6) | 27 | 205.1** (SD: 97.5) |

| Mean volume for urgency (mL) | 200 | 21 | 233 (92.64) | 31 | 222.9 (SD: 86) | 1 | 100 | 5 | 150 (SD: 50) | 20 | 213 (SD: 69.7) | 26 | 253.3** (SD: 93.5) |

**p <0.05. SD: Standard Deviation; ARS: Anorectal Sphincter; RAIR: Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex. Source: Author’s own research.

In 32 patients, manometry was performed under sedation, assessing RAIR presence and resting anal sphincter pressure. These patients demonstrated a 25% lower resting anal sphincter pressure compared to non-sedated patients, with no significant differences in anal sphincter length (Table 3).

Table 3 HRARM Parameters in Children with Constipation Under Sedation

| Parameter | Non-Sedated (Mean and SD) n = 57 | Sedated (Mean and SD) n = 32 | Standard Error (Z-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.49 (3.64) | 6.18 (4.08) | |

| Female, n (%) | 32 (56%) | 11 (34%) | |

| Mean resting ARS pressure (mm Hg) | 65.7 (32.4) | 48.1 (24.6) | 4.23 |

| ARS length (cm) | 1.9 (1.2) | 1.75 (0.8) | 0.1589 |

SD: Standard Deviation; ARS: Anorectal Sphincter; HRARM: High-Resolution Anorectal Manometry. Source: Author’s own research.

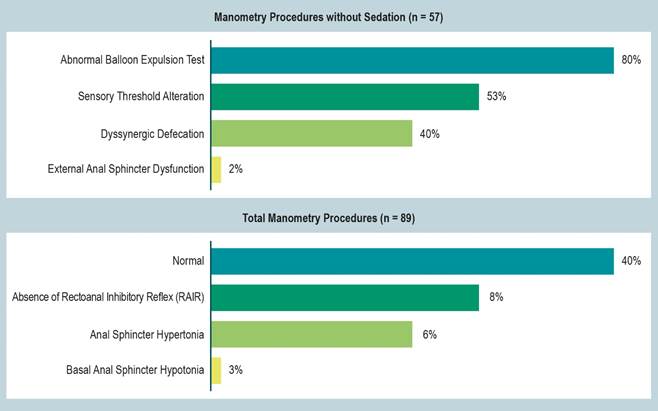

Of the total manometry procedures performed, 60% were abnormal. Among these, 8% lacked a rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR), 6% exhibited anal sphincter hypertonia, and 3% had anal sphincter hypotonia. Among the 57 manometry procedures conducted without sedation, the diagnoses included abnormal balloon expulsion test (BET) in 80%, sensory threshold alteration in 53%, dyssynergic defecation in 40%, and external anal sphincter dysfunction in 2% (Figure 1).

Patients with Dyssynergia

Among patients diagnosed with dyssynergic defecation (n = 23), 39% had type I dyssynergia, 26% had types III and IV, and 9% had type II. No differences were observed based on age or sex. Of the patients with available Bristol stool scale data (n = 17), 88% presented with Bristol types 1 and 2 (47% and 41%, respectively). The average bowel movement frequency was every 4.7 days. The mean resting anal sphincter pressure in patients with dyssynergia was 10.7% higher compared to those with constipation but without dyssynergia (63.9 versus 70.8 mm Hg). The mean anal sphincter length was 14% greater in patients with dyssynergia (1.86 versus 2.12 cm). The mean maximum voluntary contraction pressure was 170 mm Hg. Also, 78% of patients with dyssynergia failed to achieve significant anal sphincter relaxation, 87% had an abnormal BET, and 57% exhibited sensory threshold alterations (Table 4).

Table 4 Clinical and Manometric Characteristics of Dyssynergias

| Types of Dyssynergic Defecation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Todos (n=23) | Type I (n=9) | Type II (n=2) | Type III (n=6) | Type IV (n=6) |

| Age (SD) | 12 (4) | 13 (5) | 11 (1) | 13 (4) | 11 (4) |

| Female (%) | 52 | 44 | 100 | 50 | 67 |

| Mean Bristol scale (n = 17) | 1.82 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean bowel movement frequency (days) | Every 4.7 | Every 3 | Every 7 | Every 4 | Every 4 |

| Mean AS pressure (mm Hg) | 70.8 | 60 | 11 | 62 | 108 |

| Mean anal sphincter length (cm) | 2.12 | 2.6 | 4.7 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| Mean maximum push pressure (mm Hg) | 170 | 161 | 95 | 177 | 196 |

| Patients failing to relax significantly during push (%) | 78 | 78 | 50 | 100 | 67 |

| Normal balloon expulsion test (%) | 87 | 99 | 100 | 84 | 100 |

| Sensory threshold alteration (%) | 57 | 44 | 50 | 84 | 50 |

SD: Standard Deviation; AS: Anal Sphincter. Source: Author’s own research.

Findings Using the London Classification Standardization

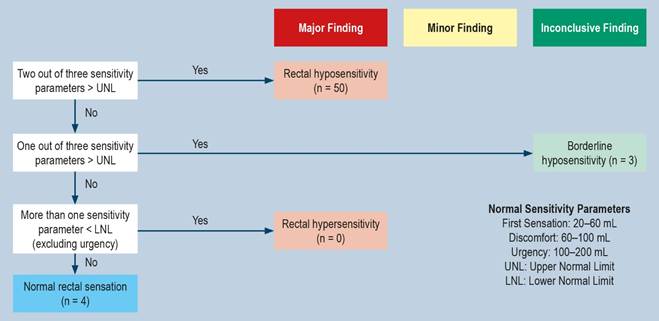

The IAPWG London Classification protocol was applied to the 57 patients evaluated without sedation (Figure 2).

Source: Author’s own research.

Figure 2 Manometry Results in Children with Refractory Constipation Standardized Using the London Classification (n = 57).

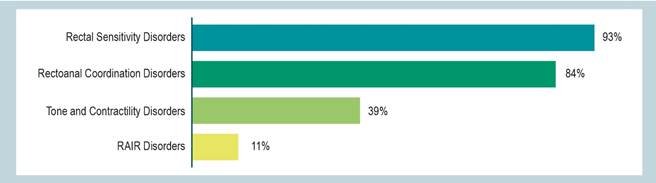

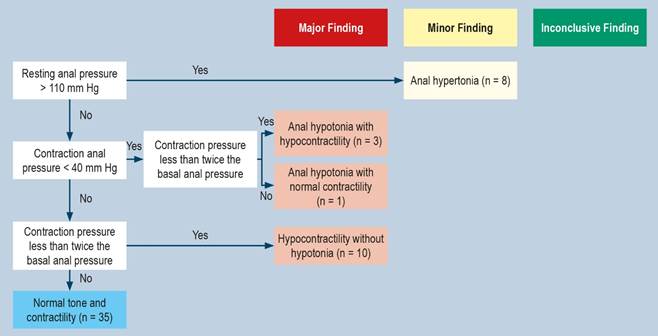

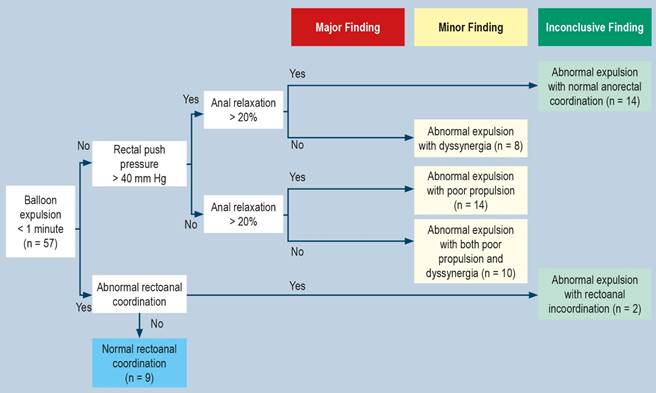

A total of 39% (n = 22) of the patients were classified as having an anal contractility disorder. Among these, 24.5% had major disorders (17.5% with hypocontractility and normotonicity, 1.8% with anal hypotonia and normal contractility, and 5.3% with anal hypotonia and hypocontractility), while 14% had minor disorders (anal hypertonia) (Figure 3). In terms of rectoanal coordination disorders, 84% (n = 48) were classified as having this condition. Of these, 56% had minor disorders (14% with abnormal expulsion and dyssynergia, 25% with abnormal expulsion and poor propulsion, and 17.5% with abnormal expulsion with both poor propulsion and dyssynergia), while 28% had inconclusive disorders (25% with abnormal expulsion but normal anorectal coordination and 3.5% with abnormal expulsion and rectoanal incoordination) (Figure 4). A rectal sensitivity disorder was identified in 93% (n = 53) of the patients. Of these, 88% had major disorders (all with rectal hyposensitivity; none presented with rectal hypersensitivity), and 5.3% had inconclusive findings (borderline hyposensitivity) (Figure 5). Finally, 11% (n = 6) were classified as having a major rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) disorder, specifically rectoanal areflexia.

Figure 3 Anal Tone and Contractility Disorders. This figure illustrates the evaluation process for anal tone and contractility, highlighting major (red), minor (yellow), and normal (blue) manometric findings. Adapted from: Carrington EV, and colleagues. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e1367916.

Figure 4 Rectoanal Coordination Disorders. This figure illustrates the evaluation process for rectoanal coordination, showing minor findings (yellow), inconclusive findings (green), and normal findings (blue) in patients undergoing rectoanal coordination tests. Adapted from: Carrington EV, and colleagues. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e1367916.

Figure 5 Rectal Sensitivity Disorders. This figure illustrates the evaluation process for rectal sensitivity, highlighting major (red), inconclusive (green), and normal (blue) manometric findings in patients undergoing rectoanal sensitivity tests. Adapted from: Carrington EV, and colleagues. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(1):e1367916.

Discussion

Anorectal manometry measures resting anal pressure, the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR), contraction pressure, and relaxation pressure, reflecting the function of the internal and external anal sphincters9. This examination is commonly used in adults for diagnosing, monitoring, and guiding the treatment of functional anorectal disorders11,17. However, in the pediatric population, there is no consensus on baseline parameters for anal sphincter function in a healthy population stratified by age10.

Evaluating contraction pressure and rectoanal pressure changes during a defecation attempt requires patient participation. In the present study, 36% of the patients were sedated, precluding the evaluation of contractility and sensitivity abnormalities. Under sedation, only RAIR and resting anal sphincter pressure can be measured. One of the primary objectives of HRARM in constipation is to demonstrate the presence of RAIR10,14, which helps rule out colonic aganglionosis and other forms of neuronal dysplasia of the myenteric plexus18, the main differential diagnoses in a constipated child. However, in cases of significant rectal dilation, low-volume distension may not trigger RAIR in a rectum with large capacity, necessitating incremental volumes10. In this study, RAIR was absent in 8% of patients. Although sedation with barbiturates, benzodiazepines, chloral hydrate, and ketamine does not affect the RAIR19, it is important to note that some studies suggest sedation might alter neuromuscular function20. As observed in this study, there was a difference in anal sphincter tone among sedated patients, which may indicate a limitation in detecting hypertonia in constipated patients under sedation. This finding suggests the need for different reference values for sedated versus non-sedated patients20.

A common anorectal disorder associated with constipation is dyssynergia21. García-Valencia and colleagues demonstrated that in patients aged 3 to 11 years with constipation and dyssynergia, internal anal sphincter pressure and maximum tolerable volume were reduced in 97.9% of cases, suggesting that dyssynergia plays a physiological role in the development and chronicity of constipation22. In our study, using a conventional classification, 40% of non-sedated manometry procedures revealed dyssynergic defecation.

The London Classification, currently applied in adults, organizes HRARM interpretation by grouping disorders of tone, contractility, coordination, sensitivity, and RAIR. For pediatric populations, it is proposed that these five groups of parameters be evaluated according to age groups. Some disorders, such as RAIR, can be assessed at all ages, while others, like tone, require an alert state, and parameters like contraction, coordination, and sensitivity require a certain level of neurocognitive development to follow instructions. When extrapolating this classification to the pediatric population, 84.2% of patients had a rectoanal coordination disorder, with abnormal expulsion accompanied by dyssynergia and poor propulsion being the most common findings. Pelvic floor dyssynergia diagnosis requires confirmatory studies, such as defecography, but it can be suspected in patients with an abnormal BET. In this study, the adult parameter for balloon expulsion time (<1 minute) was applied. However, there is no consensus regarding abnormal balloon expulsion time in the pediatric population. It is likely that balloon expulsion time varies across age groups due to differences in central nervous system maturity.

Children with chronic constipation may exhibit additional involuntary contraction of the anal sphincter, possibly to avoid the painful expulsion of large, hard stools. Yan Zhao and colleagues analyzed HRARM findings in 82 adults with chronic constipation, identifying reduced resting relaxation of the anal sphincter in 24 patients and increased resting anal sphincter pressure in 36 patients23. Alessandrella and colleagues evaluated 29 patients aged 4 to 15 years with constipation and found higher volumes required to trigger RAIR24. Additionally, resting anal pressure and maximum anal contraction pressure were lower than in healthy patients. Other studies in pediatric populations have reported resting anal pressure and maximum contraction pressure values without statistically significant differences compared to healthy children15,25.

Mortada and colleagues evaluated 50 children aged 6 to 14 years with functional constipation, observing significantly abnormal rectal sensory parameters during rectal balloon distension, including a substantially higher volume required to elicit defecatory sensation, discomfort, and urgency26. The need for higher volumes to trigger rectal sensations has been correlated with reduced defecation frequency. Prolonged stool retention can lead to rectal dilation and higher rectal sensation thresholds, progressively delaying the perception of the need to defecate and resulting in less frequent bowel movements. In our sample, the mean volume for the first defecatory sensation was 100 mL, for the first discomfort 200 mL, and for defecatory urgency 250 mL. These volumes are higher than the normal values established for healthy adults and pediatric populations15,24.

Sensory threshold alterations were identified in 53% of the manometries; however, when extrapolated to the London Classification, rectoanal sensory disorders increased to 93%, an increase of 75%. This suggests potential underdiagnosis when using conventional interpretation. While there is no established London Classification for children, extrapolating these findings from our population provides a preliminary framework for future classifications and highlights the need to revisit anorectal manometric patterns in children and adolescents. Using the London Classification, our team identified a greater number of abnormal HRARM results due to associated anorectal disorders compared to conventional interpretation.

One limitation of conducting HRARM studies in pediatric populations is the lack of normal values for Colombian children, stratified by age, sex, and anthropometric measures. Retrospective observational studies can introduce information collection bias, as variables such as height, weight, and nutritional status-factors that may influence manometric parameters-were not measured. Additionally, the use of medications affecting anorectal physiology, the duration of constipation, and the presence of other symptoms were not assessed. Despite the interpretation being conducted by two gastroenterologists (adult and pediatric), including fellows, variations in manometric classification could arise due to differing interpretation parameters.

The absence of standardized values in children complicates the comprehensive understanding of anorectal physiology. Establishing reference values in a healthy pediatric population stratified by age groups remains a significant challenge. Further studies in pediatric digestive physiology are necessary to establish normative values and classify them by age groups in Latin American populations.

Conclusions

Chronic refractory constipation in children may be associated with various abnormalities in anorectal function, and HRARM proves useful for its evaluation. Additional studies on normal anorectal physiology in children, including those conducted under sedation, are needed to establish normative parameters, thereby enabling better discrimination of abnormal findings and enhancing the diagnostic utility of these tests. Although the London Classification has not been validated for pediatrics, a subgroup-based classification adapted for children could allow a targeted approach to anorectal disorders, establishing prognoses and enabling more specific, targeted treatments.

text in

text in