Introduction

In the U.S., over 40 million Latinxs1 speak Spanish at home (United States Census Bureau, 2019). In California, 74% of the 15 million Latinx residents over the age of 5, spoke a language other than English in the home (Pew Research Center, 2014). Despite the growing number of Latinx students, there is little incentive to maintain the language and develop Spanish literacy in a comparable way to English in K-12 educational settings. Even at the university level, limited programs offer multiple courses for heritage learners (Beaudrie, 2012). These Spanish heritage language (henceforth SHL) courses structure their pedagogical goals to address both the ethnolinguistic identities of the students and the differentiated needs that distinguish them from L2 learners (Carreira, 2004; Parra, 2016).

For the context of our SHL program at the University of California, Davis, a heritage speaker (henceforth HS) is someone who was “raised in a home where a non-English language is spoken, who speaks or at least understands the language, and is to some degree bilingual in that language and in English” (Valdés, 2001). In the U.S., HS enrolled in SHL courses typically have limited literacy skills, despite a strong command of oral skills in the language (Carreira & Kagan, 2011). As a result, students are often engaging with academic literacy in Spanish for the first time in the SHL classroom and bring with them insecurities towards their own varieties and proficiency in Spanish, and express concern about speaking “correctly” (Parra, 2016, p. 189). For this reason, SHL programs have evolved their goals from standard variety acquisition to more critical approaches that center on students’ experiences and awareness of the relationships between power and language in social practices; the latter being a component of the acquisition of advanced literacy skills (Colombi, 2015).

In the process of developing academic literacy, HS are tasked with transferring their literacy skills between both languages (García, 2002; Martínez, 2007). Specifically, developing writing skills in the heritage language requires both focus on language (e.g., rich vocabulary, grammatical constructions, spelling) and functions of writing (e.g., structure, sequencing of ideas, strength of the arguments), in a similar format to language arts pedagogy in monolingual settings (Colombi, 2015). This acquisition and production of literacy in the context of a SHL program, particularly the development of vocabulary and the lexical profile of HS writing, is the focus of analysis of the current study. While previous research has documented the benefits of peer tutoring interventions in HS writing on the one hand (Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018; Reznicek-Parrado, 2018; Patiño-Vega, 2019), and the advantages of online peer tutoring in monolingual and L2 contexts on the other (Ryan & Zimmerelli, 2016; Sanford, 2021; Motallebzadeh & Amirabadi, 2011), the effects of online peer tutoring on HS writing have not been explored. Considering the changes brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic to higher education, the study reported in this paper sought to fill this gap in the literature by analyzing HS writing development with an online tutoring format compared to HS writing under the pre-pandemic in-person tutoring format.

By the same token, our study aimed to complement existing research (Alamillo, 2019; Belpoliti & Bermejo, 2020; Fairlough & Belpoliti, 2016) by employing lexical richness measures in order to better understand lexical knowledge in HS writing. While the data from prior investigations came from receptive and intermediate level bilinguals’ writing in a timed context, we wanted to consider these same measures on longer texts in which students wrote a first draft, attended a tutoring session to discuss the essay, and revised it for a second submission.

Our research was framed in the need to move the SHL courses and tutoring online because of the pandemic, which lay the path to comparing the writing development of students in both learning environments. While online peer tutoring has been prevalent in monolingual scenarios (Ryan & Zimmerelli, 2016; Sanford, 2021) and L2 contexts (Motallebzadeh & Amirabadi, 2011), it has not been explored, to our knowledge, in heritage language settings. The main advantage of online tutoring is convenience, allowing tutors to reach students who are, for a variety of reasons, unable to physically attend sessions, or simply prefer not to. In this vein, synchronous sessions, where “tutor and learner communicate in real time” (Sanford, 2021, p. 154), can closely replicate in-person interactions due to the ability to have back-and-forth exchanges. In contrast, asynchronous tutoring presents a “significant time delay between the learners’ and the tutors’ communications” (Sanford, 2021, p. 154), which allows tutors to be more careful when reviewing and responding to students’ work and gives students more time to formulate their questions and answers. As we explain in the next section, the tutors in our study used a combination of both synchronous and asynchronous communication with their students.

In order to assess the difference in tutoring modalities on writing development, two research questions were raised:

How does students’ lexical richness develop over the course of the quarter?

Is students’ lexical richness different after in-person vs. online tutoring?

To answer these questions, the development of HS writing was examined through the analysis of lexical richness as measured by the following: (a) lexical density, (b) lexical sophistication, and (c) lexical variation in both in-person and online settings. In the next subsection, we describe the characteristics of our SHL program, discuss previous studies focusing on its peer tutoring component, and explain how the shift to online instruction was adapted. Then, we present the theoretical framework of lexical richness and the methods used in this study. Finally, we address the results and discussion, implications, future directions, and conclusion.

The SHL program

Previous research on this SHL program has demonstrated that the in-person tutoring component is integral to student success (Reznicek-Parrado et al., 2018; Reznicek-Parrado, 2018; Patiño-Vega, 2019). Reznicek-Parrado et al. (2018) found that after tutoring sessions, students produced more complex and lexically dense academic writing. Furthermore, when interviewed about their sessions with the tutors, students reported a positive experience in their interactions. Not only was their confidence in their linguistic skills increased, but their security in their use of academic repertoire was strengthened. In a separate investigation, Reznicek-Parrado (2018) analyzed the relationship between students and tutors within this program, demonstrating the intersection between community building and academic literacy support. In this light, the tutors not only aided the students in their writing development by offering a space to engage with academic literacy, but also drew on their common identities as Latinx heritage speakers and first-generation college students to empower students in both academic and non-academic contexts. Finally, Patiño-Vega (2019) reported that peer tutors’ interventions over the course of an academic year resulted in long-term growth of students’ academic repertoire in both lexical development and the creation of more complex clause structures.

In the early months of 2020, the rapid onset of closures of university campuses across the U.S. due to the COVID-19 pandemic had a drastic effect on every aspect of university life, including the peer-tutoring program. The increased risk to students and staff led the shift of instruction to online formats and the implementation of safety measures for access to campus. The hurried solutions to provide classes and academic support programs for the spring term online, meant to be temporary, became the norm as the 2020-2021 academic year continued via remote learning.

Writing on the considerations of operating a tutoring center during a pandemic, Giaimo (2020) outlines some factors involved in maintaining an online format such as proper training, establishing standard practices, technology access, and working conditions; with a focus on student and employee wellness regardless of learning environment. The pandemic also disproportionally impacted women and minoritized populations (CDC, 2021), while students faced additional barriers to education in their housing, access to technology, food insecurity, mental health concerns, caregiving responsibilities, etc., making it nearly impossible to resume “business as usual” (Giaimo, 2020, p. 6).

In our SHL program, the tutors are undergraduate student employees, Latinx, many of whom are first-generation college students and women. Complete closure of the peer tutoring component would have not only affected tutors’ income and financial aid but would have also removed a key community of practice for both students and tutors (Giaimo, 2020; Reznicek-Parrado, 2018). To avoid this scenario, as soon as classes moved online, our tutors were granted access to university-supported Zoom accounts, which allowed them to work remotely and continue to support students.

For the 2020-2021 academic year, we maintained the obligatory weekly tutoring sessions. Replicating the face-to-face interactions with video conferencing via Zoom was also important as tutors had not been trained to work with student writing in a text-only online format. While the assignments and goals for tutoring are similar, face-to-face and text-only online tutoring require different training for effective pedagogy in this setting (Babcock & Thonus, 2018; Kastman Breuch & Racine, 2000). Given the unpredictable nature of the effects of the pandemic on various aspects of everyday life, we provided more flexible alternatives to both scheduling and modes of communication. While a weekly Zoom meeting was the preferred format, we also allowed students to also communicate through Google Docs and email. Additionally, if students were not able to attend their scheduled session, they were able to sign up for a make-up session at a different time during the week with another tutor. In summation, flexibility allowed for the aforementioned benefits of tutoring and the creation of academic support while acknowledging the additional limitations and barriers brought on by the context of the pandemic that both students and tutors faced.

Theoretical framework

In order to analyze HS writing development, our study drew on theories of lexical richness. In this section, we will describe the relevant advantages and uses of lexical richness in the literature.

Lexical richness metrics have been primarily used by researchers to address L2 vocabulary development (Castañeda-Jiménez & Jarvis, 2014; Cho, 2019). It is also a convenient measure of vocabulary size since it offers a snapshot of students’ repository without the need to manually code the data (Fernández-Mira et al., 2021). Another advantage is that it taps into students’ productive repertoire in contrast to traditional vocabulary tests which typically assess vocabulary comprehension (Kyle, 2020; Laufer & Nation, 1995, as cited in Fernández-Mira et al., 2021).

Previous research of language learner vocabulary has used lexical richness measures to investigate the ratio of content to function words in a given text, the size of a learners’ lexical knowledge, and the ability to use more diverse vocabulary (Achugar & Colombi, 2008; Colombi, 2003; Patiño-Vega, 2019, Laufer & Nation, 1995; Jarvis, 2002). The measures that make up an overall understanding of lexical richness are lexical density, lexical sophistication, and lexical variation.

First, the lexical density of a text indicates the ratio of lexical words to function words. According to Halliday (1994), written texts tend to be more lexically dense than oral speech. Previous studies employing a systemic functional linguistics framework of HS data in a typical face-to-face setting have utilized this measure (Achugar & Colombi, 2008; Colombi, 2003; Patiño-Vega, 2019) to demonstrate that deliberate choices are made in the two distinct contexts of oral and written speech. For HS who have had more experience using spoken language than writing academic texts, this measure informs our understanding of their ability to develop lexically dense texts in written contexts.

Second, lexical sophistication provides an understanding of the scope of lexical knowledge based on its frequency in the language. That is, spoken and written corpora can be used to know which words are most frequent in a given language (Davies, 2006). Words appearing in the first level of 1-1,000 are the most used, while words in the level of 4001-5000 are less common. A wider distribution of words across these frequency categories can indicate a learners’ proficiency level and the extent of their vocabulary knowledge (Laufer & Nation, 1995). For HS, they are expected to have a command of the first level of frequency given their exposure to the language in their home and speech communities. In turn, HS with higher levels of proficiency are able to use less frequent words in their texts as they have a more varied and large knowledge of lexical items.

Finally, the measure of lexical variation explores the diversity of the lexical items in a given text and the repetition of these items in relation to the total number of words. In written texts, a more lexically diverse text utilizes a greater number of unique words without repetition. The ability to avoid repetition and use more original words demonstrates a larger vocabulary. The most common calculation of lexical variation is a Type to Token Ratio. It measures the various types of words in a text relative to the total number of words (types/tokens) (Jarvis, 2002). By grouping lexical items by word family (e.g., saltar> salto, saltaba, saltarín), it quantifies the variety of a learners’ vocabulary within a text. The type to token ratio is useful in shorter texts, but the necessity of repetition in longer texts makes it difficult to compare texts of varying length because the score decreases as the length of the text increases. The calculation of the Guiraud Index or Root TTR (Guiraud, 1954), therefore, takes the root of the number of total tokens (types/√tokens) to account for the length (Daller, 2010; Tweedie & Baayen, 1998). Thus, a higher score of lexical variation indicates a learners’ richer vocabulary and less repetition of words within the same family.

Recent studies of Spanish HS writing have utilized lexical richness as the framework of analysis. Fairclough and Belpoliti (2016) evaluated the writing of receptive bilingual students as part of a SHL program placement test, the latter being a component of a larger study on emerging literacy (Belpoliti & Bermejo, 2019). The study included 172 essays in which the researchers analyzed the lexical richness of the writing in addition to the inclusion of English transfers (code-switching, loanwords, calques, lexical creations) throughout the texts. They found that participants had a lexical density in the mid-range based on Halliday (1994)’s scale (i.e.,46.4 %), relied heavily on vocabulary from the first 1,000 most frequent words comprising 92 % of the items, and repeated words frequently within the texts reporting an average Guiraud Index of 4.05.

Another recent study by Alamillo (2019), employed these measures of lexical richness while comparing L2 and HS writing in both informal and formal registers. The participants, who enrolled in an intermediate level L2 or SHL course, wrote two short essays on the topic of Spanglish in an informal and formal register as part of an in-class writing assignment. The results of the HS revealed higher levels of lexical density in the formal register (50.1 %) compared to the informal register (47.3 %). Similarly, the distribution of lexical sophistication used frequent words in both registers but were able to use less frequent words, employing the first 1,000 most frequent words in 73.74 % in the informal register and 71.36 % in the formal register with the remaining words falling in the 1001-5000 range. Finally, their study analyzed lexical diversity using the Hárpax Index which considers both the use of unique words and the repetitions of words within a given text. They reported a Hárpax Index score of 1.27 for the informal texts and 1.41 for the formal texts among HS data, indicating that heritage speakers demonstrate higher levels of lexical diversity in informal writing contexts.

Method

In this section, the participants recruited for this study as well as the process of data collection and analysis will be described. This study was conducted at the University of California, Davis, in a SHL program founded in 1992 (Ugarte, 1997). The year-long series is composed of three intermediate courses, each lasting 10 weeks. As customary in SHL programs, the courses focus on promoting oral and written language use, exposing students to an array of Spanish varieties, and traversing personal, professional, and academic genres (Valdés & Parra, 2018). However, a key component of the present SHL program is the implementation of a peer tutoring curriculum integrated with the courses (Ugarte, 1997). Throughout the term, students attend obligatory weekly one-hour-long sessions with the tutors to review assignments or drafts of their essays.

The peer tutors are undergraduate students HS who completed the series and were hired as tutors. The tutoring sessions provide a low-stakes environment for students to work on their assignments and build confidence in their language and writing skills throughout the course by consulting with the same tutor and establishing a familiar relationship. The format of the HS tutoring program follows a writing center model (North, 1984), where students can discuss their ideas and receive feedback. The goal of this model is to view writing as a process. This format allows students to engage with their writing, develop an awareness of audience and purpose, and promote a peer culture that values review and revision. Understanding this ultimate goal of viewing writing as a process rather than as a single act in the initial college years can have a greater impact on writing development in the long term (Sommers & Saltz, 2004).

Participants

The participants were students enrolled in the first course of our SHL series. Students in our program are primarily of Mexican or Central American origin, reflecting the demographics of the Latinx population within California (Blake & Colombi, 2013). Even though their prior experiences with Spanish in an academic setting vary, they all have the skills necessary to read texts in Spanish and write essays from one to three pages in length.

Data Collection

In order to analyze SHL writing, this study compares the evolution of lexical richness in two groups of students taking the first course of the series. The curriculum (assignments, requirements, essay prompts, etc.) was the same except for the modality: one was a face-to-face course and the other one was online. The face-to-face group (henceforth, F2F, N = 40) completed the course with in-person instruction and peer-tutoring during Fall 2019. The second group (henceforth, Online, N = 40) took the entire course with instruction and peer-tutoring online in Fall 2020.

Each group wrote three short essays, in two versions, over the course of the 10-week academic term. The students were prompted to write about language, identity, and culture, as they related to their personal experiences and the texts discussed in class. The texts analyzed in class were primarily narratives, prompting the student to respond to the situations depicted with their own experiences and personal accounts.

Each student submitted two versions of the three essays; students who did not submit all essays were excluded from the current study. The first version of the essay was graded on completion as a rough draft. The students brought their draft to the weekly peer-tutoring session to discuss with their tutor and revised it before handing in the final version. The second version of the essay was graded by the instructor. The peer-tutoring session was the only pedagogical intervention between versions 1 and 2 of the essays. While the topics of the essays for both groups were the same, the length of the assignment was one page for F2F and two pages for Online.

Data Analysis

The corpus of data consisted of 2 versions of 3 essays from 80 students for a total of 480 essays and 221,471 words. The average length of essays from both groups is listed in Table1.

Table 1 Average Word Length of Essays

| Essay draft | Essay final | |

|---|---|---|

| F2F | 337 words | 354 words |

| Online | 561 words | 595 words |

From this data, lexical richness was calculated in three measures: lexical density, lexical sophistication, and lexical variation. Using the lexical analysis software programs AntConc (Anthony, 2014) and AntWordProfiler (Anthony, 2020), words were lemmatized (grouping variants of the same root word), in order to compare distribution by frequency, count types and tokens, and separate function from content words within the corpus of essays.

It worth mentioning that apart from lemmatization of the corpus for analysis of lexical sophistication and variation, the written essays were not manipulated before analysis. That is, there were no orthographic corrections, neither words in English or other languages were eliminated, nor were lexical inventions separated.

Results

In this section, the analysis of our results for each category of lexical richness (i.e., lexical density, lexical sophistication, and lexical variation) will be outlined.

Lexical density

Following previous studies, to calculate the lexical density of each group, the total number of content words was divided by the total number of all words. Lower levels of lexical density would indicate a dependency on function words that is more reflective of oral speech, whereas higher levels of lexical density are associated with academic writing (Colombi & Harrington, 2012; Halliday, 1994). Similarly, proper nouns were removed from the total number of tokens. The remaining total of content words and function words (Hallebeek, 1986), were considered in the calculation of lexical density (Table 2).

Table 2 Average Lexical Density

| F2F | Online | |

|---|---|---|

| Essay 1 draft | 47.0% | 46.4% |

| Essay 1 final | 46.6% | 46.5% |

| Essay 2 draft | 45.4% | 47.5% |

| Essay 2 final | 46.2% | 46.8% |

| Essay 3 draft | 44.8% | 45.4% |

| Essay 3 final | 45.1% | 45.3% |

| Average | 45.9% | 46.3% |

These results validated previous studies of lexical density of heritage Spanish writers. For example, Colombi (2003) reported an average density of 44.8 % in a close analysis of one student essay. Likewise, Patiño-Vega (2019) found an average of 45.6 % for 24 students in the same level. In turn, Fairclough and Belpoliti (2016) observed an average of 46.4 % for their 172 essays from receptive bilinguals. The results in this category demonstrated that the students can write relatively lexically dense texts, accounting for no significant changes or differences between groups.

Lexical sophistication

The distribution of lexical items across the 20,000 most frequent words in Spanish (Davies, 2002) was also analyzed here. In doing so, first, the corpus was lemmatized and a list of nearly 13,000 proper nouns separated proper nouns from lexical items. This is because lemmatizing the words combines all of the derivations of a word family into one token (e.g., estudiante > estudiante, estudiantes). Names of students and cities outside of this list were categorized as other. Proper nouns were also included in a separate column to show its proportion within the essays. Items categorized as other included proper nouns not found in the proper nouns list, words beyond the 20K most frequent Spanish words, lexical inventions, anglicisms, loanwords, non-standard spellings, and words in English or other languages. Table 3 shows the distribution of unique lemmas found in each group across the most frequently used words in Spanish (Davies, 2002).

Table 3 Distribution of Lexical Items by Frequency Level

| 1K | 2K | 3K | 4K | 5K | 6K+ | Proper Nouns | Other | Unique lemmas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2F | |||||||||

| Essay 1 draft | 32.10% | 13.61% | 6.47% | 4.62% | 3.70% | 10.95% | 3.90% | 24.64% | 1514 |

| Essay 1 final | 33.24% | 14.04% | 6.85% | 4.90% | 4.10% | 11.95% | 4.10% | 20.82% | 1489 |

| Essay 2 draft | 34.04% | 13.88% | 7.10% | 4.86% | 4.03% | 12.55% | 3.58% | 19.96% | 1563 |

| Essay 2 final | 34.14% | 14.98% | 7.49% | 5.24% | 4.18% | 12.80% | 3.18% | 17.98% | 1602 |

| Essay 3 draft | 37.73% | 13.20% | 7.44% | 5.07% | 3.82% | 9.89% | 3.89% | 18.97% | 1439 |

| Essay 3 final | 37.64% | 13.79% | 7.54% | 5.30% | 4.28% | 11.07% | 3.94% | 16.44% | 1472 |

| Average | 34.82% | 13.92% | 7.15% | 5.00% | 4.02% | 11.54% | 3.77% | 19.80% | |

| Online | |||||||||

| Essay 1 draft | 28.57% | 13.05% | 7.09% | 5.81% | 4.47% | 13.02% | 3.70% | 24.31% | 1946 |

| Essay 1 final | 29.99% | 14.28% | 7.51% | 6.39% | 4.90% | 13.32% | 3.73% | 19.87% | 1877 |

| Essay 2 draft | 29.92% | 14.71% | 8.15% | 5.96% | 3.63% | 13.76% | 3.88% | 19.98% | 2012 |

| Essay 2 final | 32.07% | 15.98% | 9.01% | 6.30% | 4.22% | 14.68% | 4.06% | 13.69% | 1921 |

| Essay 3 draft | 31.42% | 16.43% | 9.45% | 5.79% | 4.60% | 13.65% | 3.71% | 14.94% | 2021 |

| Essay 3 final | 31.47% | 16.25% | 9.83% | 6.18% | 4.59% | 13.85% | 3.90% | 13.93% | 2024 |

| Average | 30.57% | 15.12% | 8.51% | 6.07% | 4.40% | 13.71% | 3.83% | 17.79% |

The 1K column represents the tokens found in the range of 1-1000 most frequent words in Spanish, 2K represents the 1001-2000 range, and so on. The 6K+ category represents 5001-20,000 range for simplification of the table. The percentages presented in this table indicate the proportion of unique lemmas occurring in each essay. For example, all the conjugations of the verb ser counted as 1 unique lemma per essay given that it occurred in every essay and yielded one token in the first 1,000 most frequent range; less frequent words, such as asimilar found in the first 5,000 range were then placed in the corresponding column.

The overall distribution of tokens by frequency shows a relatively consistent level of lexical sophistication across groups. Students were able to use a variety of highly frequent (first 1K) words representing about a third of their lemmas. Furthermore, each group demonstrated advanced lexical knowledge of relatively low frequency words (6K-20K) which made up 10-15 % of the unique lemmas across all essays.

The column other (shaded in gray) provides the most interesting changes between drafts and across the final versions throughout the course. Because the category other contains not only misspellings, but also low frequency words (i.e., 20K+) and proper nouns, the percentage in this category was not estimated to be reduced to 0 across and between essays. However, a lower percentage in this category suggests revisions and corrections to misspellings or changes to standardized spellings between drafts and essays. For example, looking at Essay 1, the category other decreased from 24.64 % to 20.82 % between drafts for the F2F group, and from 24.31 % to 19.87 % for the online group. Similarly, in terms of students’ progress across all the six writing assessments for the term, starting with Essay 1 draft and ending with Essay 3 final, the decrease was even steeper, between 8-10% (24.64-16.44 % for the F2F group and 24.31-13.93 % for the online group). Crucially, a reduction of this category for both groups suggests that they made changes to their essays and redistributed items from this category across all levels of frequency. That is, the corrections were not exclusively being recategorized to the first 1K. There was a slight increase in percentages across all frequency levels, confirming that students had a fairly extensive knowledge of low frequency words.

Comparing the two formats, the online group on average had a slightly lower percentage of words in the 1K and in the column other, and a slightly higher percentage of words in the 3K to 6K+ column compared to the F2F group. However, given the small differences, it was not possible to confirm whether these values are statistically significant.

Lexical Variation

The final measure of lexical richness is lexical variation which calculates the variety of vocabulary and the repetition of word choice within each essay. The most common calculation for lexical variation is the type-to-token ratio (TTR). The TTR divides the total number of word types by the total number of words in a given text. However, for longer texts the number decreases as words are repeated. Since the essays in this study had a different length between the two groups, TTR would not provide an accurate comparison. A second calculation that accounts for variation in word length is Guiraud’s index (Root TTR) which divides the total number of word types by the root of the total number of words (Daller, 2010; Van Hout & Vermeer, 2007). The Root TTR was calculated for the analysis of lexical variation in order to better compare the two modalities. Table 4 shows the averages per group of Types, Tokens, the TTR, and Root TTR by group and essay.

Table 4 Average Types, Tokens, TTR, Root TTR

| F2F | Online | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types | Tokens | TTR | Root ttr | Types | Tokens | TTR | Root ttr | |

| Essay 1 draft | 143.40 | 337.20 | 0.43 | 7.82 | 204.15 | 580.10 | 0.36 | 8.53 |

| Essay 1 final | 146.75 | 351.00 | 0.42 | 7.85 | 206.98 | 589.13 | 0.36 | 8.55 |

| Essay 2 draft | 143.15 | 354.18 | 0.41 | 7.63 | 196.58 | 549.25 | 0.37 | 8.43 |

| Essay 2 final | 149.10 | 368.50 | 0.41 | 7.79 | 207.65 | 606.48 | 0.35 | 8.45 |

| Essay 3 draft | 129.35 | 318.53 | 0.43 | 7.25 | 195.93 | 553.85 | 0.36 | 8.35 |

| Essay 3 final | 136.33 | 341.55 | 0.40 | 7.37 | 205.75 | 589.50 | 0.36 | 8.50 |

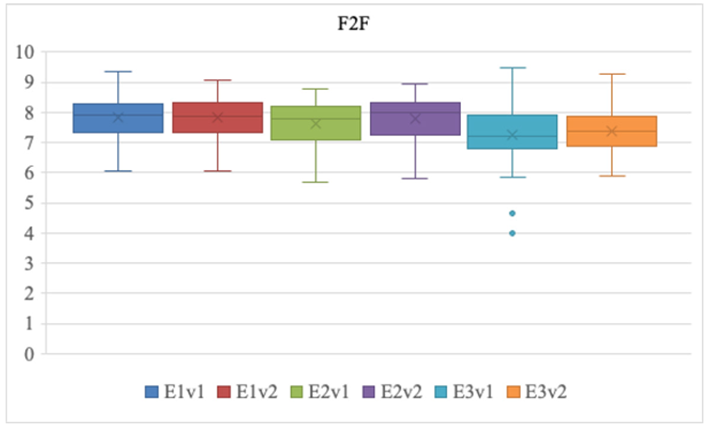

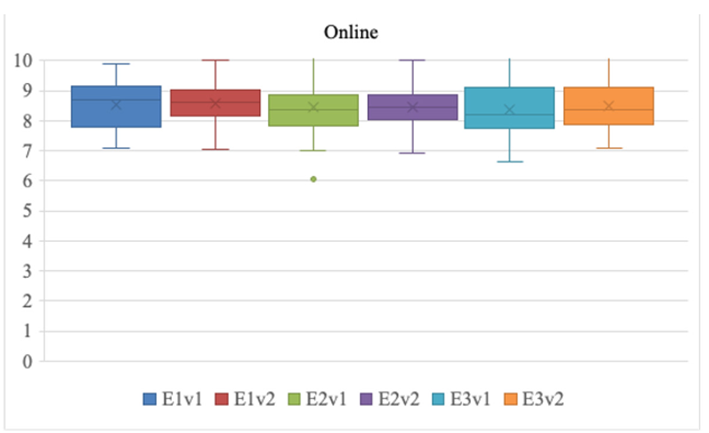

Taking into account students’ lexical variation measures for each essay, a two-way ANOVA was performed with the factors Group (i.e., F2F, Online) and Essay (i.e., E1d, E1f, E2d, E2f, E3d, E3f). The results revealed a highly significant main effect of Group (p<0.001), indicating that the online group has a significantly greater lexical variation than the F2F group.

Independent t-tests of the individual results of the lexical variation measure were also conducted comparing essays within groups and between both groups. Within both groups there was no significant improvement of lexical variation between drafts and final versions. However, a significant difference between both groups for every essay draft and final version was found. The online group showed higher levels of lexical variation in every instance. The results of the t-tests between groups are outlined in Table 5.

Table 5 Mean, Standard Deviation, T-Test Results

| F2F | Online | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t-test | |

| Essay 1 draft | 7.82 | .73 | 8.53 | .82 | -4.08*** |

| Essay 1 final | 7.85 | .71 | 8.55 | .76 | -4.28*** |

| Essay 2 draft | 7.63 | .70 | 8.43 | .92 | -4.36*** |

| Essay 2 final | 7.79 | .76 | 8.45 | .75 | -3.92*** |

| Essay 3 draft | 7.25 | 1.07 | 8.35 | .93 | -4.89*** |

| Essay 3 final | 7.37 | .75 | 8.50 | .85 | -6.31*** |

| ***p < .001 |

At the individual level, changes between both essay drafts shows an overall profile of lexical variation throughout the academic term. In Figures 1 and 2 the individual student Root TTR for each essay is displayed by group.

Overall, both groups have relatively high levels of lexical variation, indicating that the students had sufficient lexical knowledge to avoid repetitions of words throughout the essays. Furthermore, there was a slight increase of Root TTR between the first and second version of each essay, suggesting that the learners revised the first draft after or during the tutoring sessions. Indeed, changes in variation corresponded to selecting different words, revising sentences, correcting orthographic errors, etc. While the overall Root TTR within each group did not change drastically throughout the course, both groups produced texts with comparable levels of lexical variation.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this section, the findings will be discussed in relation to our research questions. In addition, limitations of the current study will be presented, and pedagogical implications for tutor training will be examined.

Research question 1: How does students’ lexical richness develop over the course of the quarter?

Considering the measures of lexical richness chosen for this study, significant evidence of writing development for lexical variation was found but this was not the case for density or sophistication. In terms of lexical density, no noticeable change was evident between essays for either group, with the proportion of content to function words staying between 45-47 % throughout the 10-week term. This similarity indicates that the in-person and online settings did not have an impact on lexical density. The lexical density percentage observed in our study makes it comparable to those reported in previous studies on lexical density in HS writing (Colombi, 2003; Fairclough & Belpoliti, 2016; Patiño-Vega, 2019). For instance, for the same SHL program, Patiño-Vega’s (2019) research found similar rates of lexical density in 24 students from three groups with varying educational experience in Spanish. While her study found growth in terms of lexical density, it happened over the course of three terms (30 weeks).

In terms of lexical sophistication, both groups demonstrated a comparable distribution of lexical items across frequency levels. Even though it was not possible to statistically verify the changes in the distribution of percentages, some tendencies providing an interesting insight into HS writing were observed. Fairclough and Belpoliti (2016) found that low proficiency speakers produced 92 % of their lexical items within the first 1K frequency, a dependency that reflects the level of beginning L2 learners (Laufer & Nation, 1995). While comparing these results to previous studies was not possible here because of differences in methods of analysis, it was possible to get an understanding of the students’ vocabulary knowledge and choice throughout the course. First, the decrease of the category other indicates that they did revise and make corrections to their essays between the first and second draft and made fewer errors by the end of the course. Further coding of this category would be beneficial in future studies in order to delve deeper into specific changes and subcategories in this particular subset of the data. Second, the distribution of the lexical items in the essays by level of frequency suggest that students were able to write using words beyond the most basic vocabulary in order to complete the assigned task.

In the final measure of lexical variation, it was found that the online group had more lexically diverse essays than the F2F group for both drafts and final versions of each essay. In this regard, students in the online group were able to use more lexical items throughout their essays with fewer repetitions within the text. Compared to the receptive bilingual learners in Fairclough and Belpoliti (2016), who reported an average score of 4.05, the results of both groups based on the calculation of Guiraud’s Index showed that the students in our study had a more advanced command in writing without repeating words in their essays. For example, the average Root TTR of the final version for the F2F group was 7.67 and 8.50 for the online group in the present study. Together with the results of lexical sophistication, students demonstrated sufficient lexical knowledge beyond the most frequent words to write longer texts of 1-2 pages without the need to make repetitions throughout the essays.

Research question 2: Is students’ lexical richness different after in-person vs. online tutoring?

Analyzing the data based on the three aforementioned measures, it was shown that the online group performed significantly better with respect to lexical variation, displaying higher rates than the F2F group. However, there were no other measures that indicated a different level of lexical richness between the groups. In terms of lexical density and lexical sophistication, both groups seemed to be at the same level. For these measures of lexical richness, the implementation of peer-tutoring in an online setting did not negatively impact their writing development.

On the other hand, the online group had significantly higher levels of lexical variation across all essays, which might have to do with the modality. In contrast to face-to-face peer tutoring, online tutoring sessions provide tutor and tutee with easy access to the essay document and the ability to edit in real time, as opposed to taking the comments into account after the in-person session (Babcock & Thonus, 2018). Presumably, the use of Google Docs may have allowed the students and tutors to keep track of comments, suggestions, and changes while revising the essays in a way that cannot be done on paper. This digital record aids students in remembering the tasks their tutors suggest for remaining revisions of the essays. Therefore, given that tutors’ comments could be written via chat (either in Zoom or Google Docs), delayed dynamics were established in the session, leading to clearer and more direct feedback. Kastman Breuch & Racine (2000) make a similar point, highlighting the benefits of a writing-mediated interaction since it

provides opportunities for reflection, consideration, and unlike in face-to-face tutoring, an opportunity to edit and take back words. The benefit of using this online environment for clients is that they can receive careful, well-considered responses to their own work that models the type of clear, communicative writing for which they strive (p. 248).

Implications for tutor training

The pedagogical implications of this study are that firstly, while the participants demonstrated an advanced use of the language, more explicit tutor training in any modality (online and face-to-face) can be tailored to target lexical richness in student writing. For example, future training could address how tutors can provide students with more direct instruction on sentence structure, which could in turn lead to increases in the rates of lexical density in HS writing. In addition, tutors can recommend the use of resources such as a dictionary or thesaurus to avoid standardized orthographic errors and the repetition of lexical items. This strategy may foster the use of less frequent words and more diverse word choice in academic writing, increasing the measures of lexical sophistication and variation. Even under the post-pandemic virtual conditions, our results suggest that the very act of revision mediated by tutoring does direct students’ attention to writing as a process, influencing at least some indicators of lexical richness such as decreasing the number of non-words (i.e., the category other: misspellings, English words, etc.) and increasing lexical variation.

Similarly, our study gives prominence to the role of time in feedback and revision. Thinking about how to express ideas before writing them in the Google Doc not only helps students be more careful and thorough, but it might also allow tutors to be more directive and deliberate in their comments and suggestions. For example, instructing tutors to keep a session journal or simply summarizing their recommendations could be another consideration worth emphasizing in tutor training. As Kastman Breuch & Racine (2000) explain:

Not only do text-only environments encourage students to write, but they also encourage tutors to write in the ways that writing centers promote: considering our audience’s needs, anticipating readers’ reactions to text, and writing in a clear, concise, and informative style that does not laud authority nor condescend. Tutors need a solid understanding of the writing process and an appreciation of written work, and they must also be able to articulate that knowledge and then communicate it effectively to the clients with whom they work (p. 248).

Finally, our study confirmed the valuable impact of tutors on students’ wellbeing. In addition to writing support, writing centers create community, promoting opportunities for “socialization and reflection” (Giaimo, 2020, p. 7). For example, in our program, the tutors also serve as mentors to their tutees, and it is important to maintain this interpersonal relationship, despite the limitations of being online. Even faced with the emotional and financial stress of the pandemic on writing center students and staff (Giaimo, 2020), having access to this kind of peer-tutor mentorship still contributed to the online groups’ improved performance revising essays. At the end of the course, the students provided feedback regarding their relationship with Spanish, their thoughts on tutoring and its role as a component of the class. In comments collected as part of this survey (1-2) we found that students claimed tutoring was helpful for their success in the course:

I got along well with my tutor and I really benefited from hearing her input and advice on how to improve my essays. [Tutor] was very kind and we formed a bond with each other. It was nice having one on one support especially right now with online learning. (G2:45, survey).

Tutoring has played an important role in adapting and being successful in the course. I think my essays were stronger because my tutor gave me feedback. (G2: 74, survey).

For the development of SHL writing support resources, the success of tutoring in an online format offers the flexibility for establishing or expanding already existing programs. Without the limitations of providing physical space and resources, technology such as video conferencing via Zoom and simultaneous document viewing with Google Docs allow for online tutoring as a viable alternative to face-to-face tutoring. As COVID-19 vaccinations are made widely available and safety protocols allow universities to re-open, implementing online tutoring as an additional or supplemental format to face-to-face tutoring makes tutoring more accessible for all students and measurably contributes to HS writing development.

Future Directions & Limitations

Although this study features a similar framework for measuring lexical richness of HS writing to the ones employed by Alamillo (2019) and Fairclough and Belpoliti (2016), it is not feasible to directly compare our results with theirs based on a difference in methods of analysis. First, for lexical sophistication, spelling errors, English or words from other languages, inventions, anglicisms, calques, etc., were not identified or changed as part of the calculation. Their analyses are able to provide a clearer understanding of distribution including all tokens of lexical sophistication in a way that is not attainable with a larger corpus of data such as ours. Furthermore, the students in these previous studies were only allotted a certain amount of time to complete the writing tasks, while our students wrote the essays on their own time, met with a peer-tutor, and then revised the essays for a second submission. This provides ample opportunity to look up synonyms of words, spelling, definitions, etc. throughout the writing process, which could have contributed to higher lexical richness.

The second limitation of the present study was the fact that it was only possible to analyze data from the first level of the three-course series. A future study taking a longitudinal look beyond a single academic term might provide a more comprehensive understanding of HS’ writing development. For example, in a study of lexical richness involving L2 learners, Castañeda-Jiménez and Jarvis (2014) correlated this measure with course level, showing that students’ scores increased as they progressed through five different courses.

Additionally, expanding the corpus of essays throughout the entire year with online tutoring and instruction would provide insight on how students learn to write across various genres and topics. The inclusion of tutoring in the series provides students the guidance to learn writing as a process, not a single outcome. A year-long longitudinal study would be beneficial to understand HS writing as they learn to acquire the skills to convey complex ideas, create arguments, and be deliberate with their word choice.