INTRODUCTION

The colombian creole donkey (CCD) is the result of the unstructured crossing from the donkey breeds brought to the American continent, during the colonization time (Jordana et al. 2016). Since then, CCD has contributed to the agricultural and social development in all of Colombia's regions. The CCD can be found throughout the national geography. However, historically, the Caribbean region has stood out for making great use of this genetic resource, both in its productive and cultural activities. In general, Creole donkeys are considered rustic, easily adapted to climatic conditions, with low nutritional requirements, and are resistant to diseases and ectoparasites, therefore they do not require special handling practices, have low maintenance costs, and have great strength and docility (Silva-Gómez et al. 2017).

Currently, the donkey inventory of the country is unknown, but it is presumed that its population decreased by 80 % between 1995 and 2013 (Medina-Montes et al. 2020). Therefore, it is possible to indicate that the CCD is at risk of extinction, like other colombian creole breeds, such as chickens (Montes et al. 2019), sheep (Hernández H. et al. 2019; Medina-Montes et al. 2021), cattle (Delgado et al. 2012) and pigs (Revidatti et al. 2014). A possible explanation for this phenomenon is the introduction of new breeds brought from other countries and the carrying out of indiscriminate absorbent type crosses, reducing the number of the inventory and the genetic diversity. Additionally, in the Caribbean region, the increase in the use of alternative means of transport and work such as motorcycles, together with the illegal trade to slaughter donkeys to obtain their skin and meat (Silva-Gómez et al. 2017; Medina-Montes et al. 2020), are two additional reasons that could explain this alarming decrease in the CCD inventory.

On the other hand, the decrease in the number of animals leads to the loss of the diversity of animal genetic resources (Salamanca Carreño et al. 2015), considered an important component of global biodiversity, which is a key element and raw material for genetic improvement and adaptation to environmental conditions global (Boettcher et al. 2010). In Colombia, creole breeds have long been considered a natural and irreplaceable reservoir of genetic variability (Correa A. et al. 2015), due to their genetic origin, population structure, evolution and adaptation to tropical conditions due to more than 500 years and that possibly have keep gene variants already absent in foreign animal breeds and that in future events could be necessary for an introgression. Therefore, knowledge of morphometric variables is an important step for planning long-term sustainable conservation strategies (Rosenberg & Kang, 2015).

However, the CCD has remained forgotten by the scientific community; an example of this is evidenced in the scant information available on this genetic resource, not only in aspects such as its functional development, physiology, and pathology but also in zootechnical, morphological, and ethnological aspects. Based on the above, Medina-Montes et al. (2020) reported the first findings on genetic diversity using dominant molecular markers, but data related to its morphology and ethnology are non-existent. Therefore, basic studies, where morphological characterization methodologies are carried out, can be the starting point for future conservation plans for the breed. Therefore, this work aimed to characterize the zoometric and ethnological traits of CCD in five natural subregions of the department of Sucre.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Populations and morphological measurements. Overall, 100 animals (20 no-emasculate males) from each of the natural subregions in the department of Sucre, Colombia: Golfo de Morrosquillo: GM (tropical dry forest (t-df), the average temperature was 28.7 °C, 2 meters above sea level (m MSL) and precipitation was 2.123 mm per year); Montes de María: MM (t-df zone, the average temperature was 27.7 °C, 1.000 m MSL and precipitation to 1.275 mm per year); Mojana: MO (t-df zone, the average temperature was 31 °C, 25 m MSL and precipitation 125 mm per year); San Jorge: SJ (t-df zone, the average temperature of 31 °C, 25 m MSL and precipitation was 125 mm per year) and Sabanas: SA (t-df zone, the average temperature of 26.1 °C, 213 m MSL and precipitation 2274 mm per year). The average age was 4.7 ± 1.0 years old. The body weight of the animals was estimated using an equinometric weighing tape measure (inalmet ®) following the manufacturer's instructions, due to the impossibility of quantifying the weight using a scale. A set of 28 morphometric measurements (cm) were recorded, taken with a zoometric stick, tape measure, and thickness compass (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015; Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016a; Sargentini et al. 2018).

Values assessed were facial length (FaL), length of the front (FoL), front length (FrL), head length (HL), full head length (FHL), and head width (HW). The measurements at the trunk level were: thoracic circumference (ThC), height at the withers (HeW), dorsal-sternal height (DSH), height at the sternum (HeS), height at the back (HeB), height at the back (HetB), height at the croup (HeCro), height to the pelvis (HeP), height to the ischium (HeI). The anterior height of the back (aHeB). The measured width was: bicostal width (BiW), posterior chest width (pChW), anterior rump width (aRuWu), interiliac distance (InD) and posterior rump width (pRuW). The measured lengths were: body length (BoL), back length (BaL), scapula length (ScL), ilio-ischial length (ILisL), and occipital-coccygeal length (OcCoL). In the extremities, the perimeter of the anterior cane (PeraC) and the hock lift (HoL) were determined (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015; Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016a; Sargentini et al. 2018).

Index estimation. From the biometric measurements, the ethnological indices were estimated: corporal index (CI = BoL/ThC* 100), thoracic index (ThI = BiW/DSD*100), ilio-ischial index (ILIsI = InD/ILisL*100), compactness index (ComI = Weight/HeW*100), pelvic index (PelI = ARuW/ILisL*100) and cephalic index (CepI = HW/Fal*100). The productive indices were also estimated: proportionality index (ProI = HeW/OcCoL*100), relative depth index (ReDeI = DSD/HeW*100), posterior foot index (PoFI = HoL/HeP*100), firewood load index (FrLI = PeraC/Weight*100) and dactyl-thoracic index (DaThI = PeraC/ThC*100) (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015; Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016b; Sargentini et al. 2018).

Analysis of data. Normality and homogeneity of variances tests were performed in each of the morphometric variables to confirm the validity of the data to factor analysis using the Kolmogórov-Smirnov test, Shapiro-Wilks test, and Bartlett sphericity test, where none of the variables showed statistical differences in the assumptions (at 5 % significance).

The mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV) were estimated for each of the grouped morphometric measures for each of the department's subregions. The CV values under 10 % were considered with little variability. Likewise, an analysis of variance and a Tukey-Kramer test (p ≤0.05) were performed to determine morphometric differences according to the subregion. Subsequently, a hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using the furthest neighbor clustering method and the squared Euclidean distance as an interval measure (Sargentini et al. 2018). The determination of the morphostructural homogeneity of the CCD within each of the evaluated subregions was carried out using the coefficient of variation for each measure analyzed. Also, the morphostructural harmony was evaluated by quantifying the percentage of positive and significant correlations of the Pearson correlation coefficients between the variables evaluated for each of the analyzed subregions (Flórez et al. 2018). The ethnological and productive indices were analyzed using descriptive statistics and analysis of variance between the study subregions. All statistical procedures were performed through InfoStat® version 2016I (Di Rienzo et al. 2016).

The whole procedure such as sample collection, handling, and conservation was approved by the Institutional Committee of Bioethics of the Universidad de Sucre, and those were conducted with the ethical, technical, scientific, and administrative standards for research on animals contained in “Ley 84 de 1989 del Congreso Nacional de Colombia”.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This is the first report on the zoometric and ethnological characterization of the colombian creole donkey in the country. The estimated weight of the donkeys was 126 ± 19.4 kg. Whereas, the age varied between 3 and 7 years, with an average of 4.7 ± 1.0; both measurements varied between subregions (p <0.05). The average age found represents about 10 % of its useful life, so it is considered a young herd, taking into account that the longevity of the species can reach up to 50 years (Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016a; 2016b). An ideal situation was found since it allows planning to work with the species on issues related to reproductive management, genetic improvement, and conservation plans.

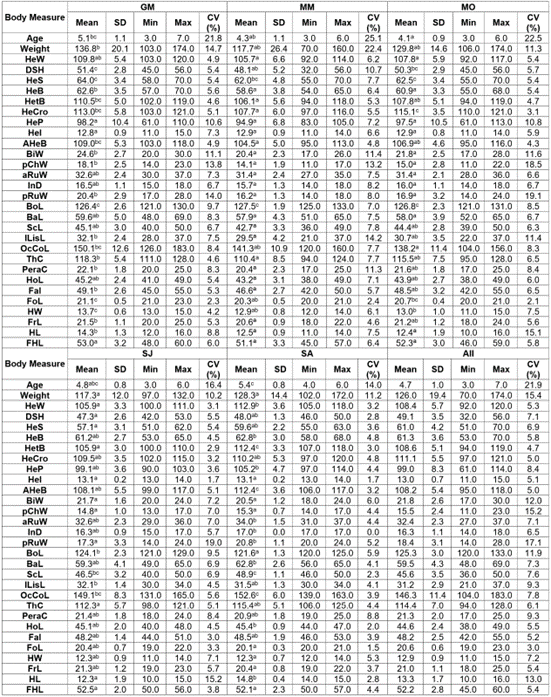

With the zoometric measurements taken in the head (Table 1), only the full head length (FHL) did not have a significant variability (p >0.05) between regions. While, for the other head measurements (Fal, Fol, HW, Fil, and HL), the CCDs of the GM subregion had the highest values (p <0.05). The measurements of the cephalic region showed low variation and presented a longer head than it was wide. These values were higher than those reported in Cuban donkeys (Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016a; 2016b) and Serbian donkeys (Ljubodrag et al. 2015), but slightly lower than those reported in donkey breeds: amiata from Italy (Cecchi et al. 2007), catalan (Jordana & Folch, 1998) and andalusian (Miró-Arias et al. 2011) from Spain. Cephalic variables appear to receive little influence from the environment, but they can provide important evidence of animal genetic diversity (Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016a).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and comparison of averages, for 28 morphometric measures, age and estimated weight, in colombian creole donkeys (CCD), from the five natural subregions from department of Sucre.

a,b,c Different letters in the same line indicate statistically different averages between subregions (p <0.05). GM: Golfo de Morrosquillo. MM: Montes de María. MO: Mojana. SJ: San Jorge. SA: Sabanas. SD: standard deviation. Min: minimum. Max: maximum. CV: coefficient of variation. HeW: height at the withers. DSH: dorsal-sternal height. HeS: height at the sternum. HeB: height at the back. HetB: height at the back. HeCro: height at the croup. HeP: height to the pelvis. HeI: height to the ischium. aHeB: anterior height of the back. BiW: bicostal width. pChW: posterior chest width. aRuW: anterior rump width. InD: interiliac distance. pRuW: posterior rump width. BoL: body length. BaL: back length. ScL: scapula length. ILisL: ilio-ischial length. OcCOL: occipital-coccygeal length. ThC: thoracic circumference. PeraC: perimeter of the anterior cane. HoL: hock lift. FAL: facial length. FoL: length of the front. HW: head width. FrL: front length. HL: head length. FHL: full head length.

In the two measurements taken in the extremities (PeraC and HoL), the donkeys from the MM subregion presented the lowest measurements (p <0.05). The measure evaluated PeraC was higher in the donkeys of the GM and the HoL of the donkeys of the SA region (Table 1). The PeraC and HoL measurements were superior to those presented in different breeds around the world (Jordana & Folch, 1998; Cecchi et al. 2007; Miró-Arias et al. 2011; Pimentel et al. 2014; Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016a).

Differences between the subregions of the department for the eight elevations evaluated at the trunk level were found (p <0.05). The five measures of width or diameters (BiW, pChW, aRuW, InD, and pRuW), were significantly higher (p <0.05) in the donkeys of the GM, while the lowest values were presented by the donkeys of the regions MM and MO. The lengths, body length (BoL), back length (BaL), scapula length (ScL), ilio-ischial length (ILisL), and occipito-coccygeal length (OcCoL), varied significantly between the subregions of the study. The thoracic circumference averaged 114.4 ± 7.0 cm, with the highest value in the GM subregion and the lowest in the MM subregion (Table 1). In the measurements of the trunk region, a greater height at the rump was found, and a lower height at the withers, bicostal width, and thoracic perimeter than other donkeys in the world (Jordana & Folch, 1998; Cecchi et al. 2007; Pimentel et al. 2014; Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016a). Back length (BaL) and body length (BoL) were similar to the results reported in donkeys from Italy (Sargentini et al. 2018). These results allow showing the conformation of a donkey suitable for the saddle and hiking, in which the long back, together with a large chest should predominate. The foregoing coincides with the management given to the CCD in the MM and SA subregions, where it is used as a means of transport (Medina-Montes et al. 2020). Also, a large barrel (bicostal width, BiW) indicates a suitable respiratory biotype for dynamic activities, as occurs in the GM and SJ subregions, where the use of CCD is more for the loading of inputs and agricultural products. Additionally, the use of donkeys for onotherapy requires short and long animals since it facilitates the human approach during donkey therapy (Karatosidi et al. 2013). From this point, the CCD presented a total length (OcCoL) slightly higher than the reports of Ethiopian donkeys (Kefena et al. 2014), Czechs (Kosťuková et al. 2015), Italians (Sargentini et al. 2018), and Cubans (Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016a), suggesting potential new use of the species.

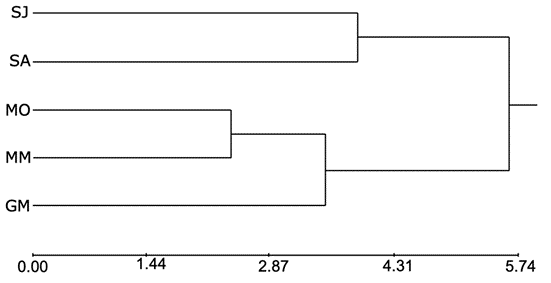

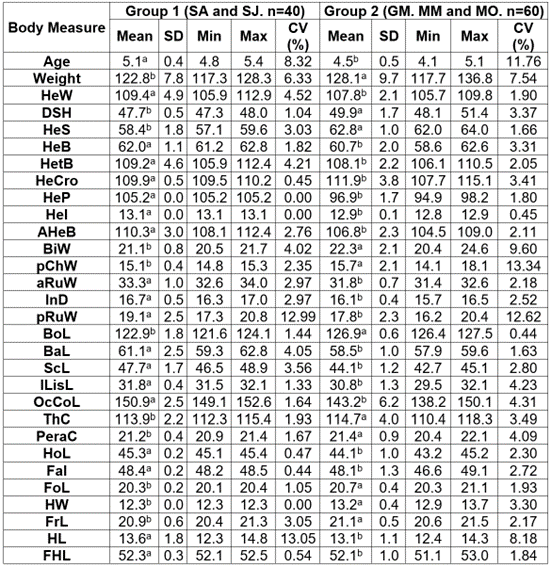

The results seem to indicate that the morphological variation is not only related to the productive function of the CCD within the production system, but also to the geographical and climatic conditions in which they were reared. This is confirmed by hierarchical cluster analysis. The studied subregions allowed the formation of two groups (Figure 1), the first made up of the SJ and SA donkeys and the second made up of the MO, MM, and GM animals. All the zoometric measures evaluated for each of the groups (Table 2) varied significantly (p <0.05). Thus, group one was superior in 60.1 % of the zoometric measurements, showing a higher CCD at the withers and larger hindquarters. For its part, group two presented a CCD of greater amplitude in the anterior region and larger head. Coincidentally, the two groups formed have similar geographic proximity and agroclimatic conditions, although the potential use of the donkey in each of them is potentially different. In addition, the absence of genetic improvement programs within the species may lead to increased inbreeding within each subregion. All this agrees with work on genetic diversity previously carried out by Medina-Montes et al. (2020) in this same department and with some of these same animals. Another factor that could affect the organization of the groups is related to the grouping method used. The Euclidean distance, which, although it is simple to estimate, has the disadvantage of being sensitive to the units of measurement of the variables (Arredondo et al. 2015). Thus, variables of greater magnitude will contribute to a greater extent to the observed variation than variables of lesser magnitude. The above explains why the groups are determined by high-value morphological variables such as lengths, widths, and perimeters taken at the level of the trunk.

Figure 1 The hierarchical conglomerate of classification by the similarity of the colombian creole donkeys (CCD) of the five natural subregions from department of Sucre. GM: Golfo de Morrosquillo. MM: Montes de María. MO: Mojana. SJ: San Jorge. SA: Sabanas.

Table 2 Body measurements of the colombian creole donkey (CCD) groups according to the hierarchical cluster analysis.

a,b Different letters in the same line indicate statistically different averages between subregions (p <0.05). GM: Golfo de Morrosquillo. MM: Montes de María. MO: Mojana. SJ: San Jorge. SD: standard deviation. Min: minimum. Max: maximum. CV: coefficient of variation. HeW: height at the withers. DSH: dorsal-sternal height. HeS: height at the sternum. HeB: height at the back. HetB: height at the back. HeCro: height at the croup. HeP: height to the pelvis. HeI: height to the ischium. aHeB: anterior height of the back. BiW: bicostal width. pChW: posterior chest width. aRuW: anterior rump width. InD: interiliac distance. pRuW: posterior rump width. BoL: body length. BaL: back length. ScL: scapula length. ILisL: ilio-ischial length. OcCOL: occipital-coccygeal length. ThC: thoracic circumference. PeraC: perimeter of the anterior cane. HoL: hock lift. FAL: facial length. FoL: length of the front. HW: head width. FrL: front length. HL: head length. FHL: full head length.

The variation degree in the body structure is used to establish morphostructural homogeneity. The coefficient of variation is used as an indicator, thus, the higher the CV, the lower the homogeneity (Flórez et al. 2018). It is considered that a CV lower than 4 % indicates a great homogeneity, between 5 and 9 % indicates a medium degree of uniformity and if it is greater than 10 %, a high variability should be considered in the context of the sample studied (Salamanca Carreño et al. 2015). The coefficients of variation for the entire population and trunk measurements varied between 5.0 and 17.1 % (Table 1). For measurements in extremities between 5.5 and 9.3 %. Finally, for the head measurements between 3.0 and 13.0 %. The lowest average CV was presented by the donkeys from the SA subregion, while the highest value was presented by the animals from the MO subregion (Table 1). In this sense, the measurements at the extremities of the CCD indicate a medium homogeneity, while the measurements of the trunk and head have low and medium-low homogeneity, respectively. There are no reports on this type of determination in other breeds of donkeys in the world, however, in araucanian creole horses of Colombia (CCC), CVs lower than 10 % are presented (Salamanca Carreño et al. 2015) and in colombian hair sheep (OPC) values lower than 13.63 % (Flórez et al. 2018).

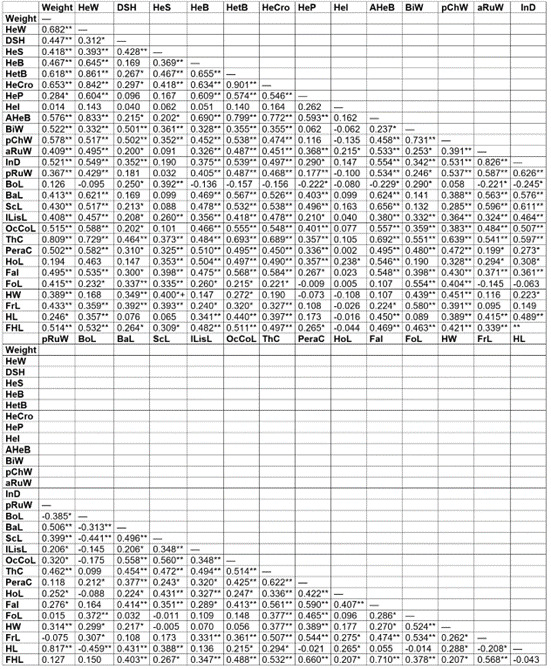

Most of the genes that influence structural conformation are not local, but general. Hence the importance of estimating the harmony of the morphostructural model, which is made from the amount of significant positive correlations between the measurements. Therefore, the higher this percentage, the more structurally harmonic the animal is (Flórez et al. 2018). These results showing an average structural harmony in the donkeys of the MM (53.2 %) and MO (47.3 %). While, the asses of GM, MA, and SJ presented low structural harmony, with values of 38.2, 19.7, and 18.7 %, respectively. On the other hand, when analysing all the subregions as a single population and the 406 possible correlations, the percentage of positive and significant correlations increased to 74.9 %, indicating high morphostructural harmony (Table 3). This last value is unusual in an autochthonous population without racial recognition. Although, the absence of reproductive management plans can increase consanguinity and favour positive correlations. Compared with other reports of colombian creole species, morphostructural harmony differed from CCC and OPC where only 26.9 and 62.3 % of significant positive correlations were reached, respectively (Salamanca Carreño et al. 2015; Flórez et al. 2018).

Table 3 Pearson's correlation coefficients between the variables measured in colombian creole donkeys CCD.

*p <0.05, **p <0.001. HeW: height at the withers. DSH: dorsal-sternal height. HeS: height at the sternum. HeB: height at the back. HetB: height at the back. HeCro: height at the croup. HeP: height to the pelvis. HeI: height to the ischium. aHeB: anterior height of the back. BiW: bicostal width. pChW: posterior chest width. aRuW: anterior rump width. InD: interiliac distance. pRuW: posterior rump width. BoL: body length. BaL: back length. ScL: scapula length. ILisL: ilio-ischial length. OcCOL: occipital-coccygeal length. ThC: thoracic circumference. PeraC: perimeter of the anterior cane. HoL: hock lift. FAL: facial length. FoL: length of the front. HW: head width. FrL: front length. HL: head length. FHL: full head length.

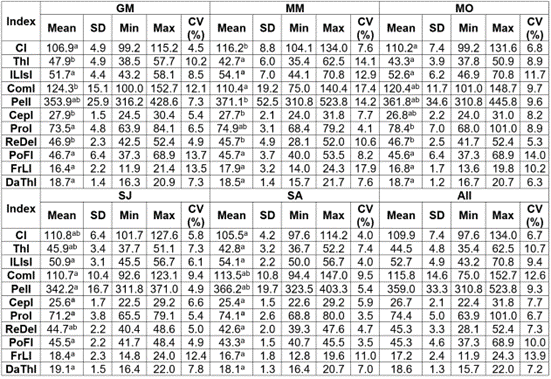

Of the six estimated ethnological indices (Table 4), only the ilio-ischial index (ILIsI) did not vary significantly between subregions. The donkeys from the GM subregion presented the highest values (p <0.05) in the corporal index (CI), compactness index (ComI), and cephalic index (CepI), on the other hand, the CCDs from the MM region presented the corporal index (CI) and pelvic index (PelI) higher. The estimated body index shows a long-line donkey, as the donkeys of the Calabria (101.94 ± 2.9) (Liotta et al. 2014) and Tuscany (91.2 ± 8.7) regions (Sargentini et al. 2009) in Italy, but also in the creole donkeys of Cuba (91.79 ± 1.9) (Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016b) and Ecuador (100.0 ± 1.0) (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015). In the same way, the thoracic index (ThI), categorizes the CCD as longilinear, like the Italian donkeys (Sargentini et al. 2009; Liotta et al. 2014) and other Creoles (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015; Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016b). The CCD shows a proportionate croup, although, for pelvic index values greater than 100, this is classified as concavilinear. This agrees with the Ecuadorian donkey with an index of 112.6 (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015) but does not agree with the Cuban donkey (Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016b) with an index of 92.6, showing a rump of convex lines. The estimated compactness index was higher than that reported in Calabrian donkeys (Liotta et al. 2014), indicating a longline animal. The cephalic index (CepI) refers to the harmony of the proportions of the head in general, this data classifies the CCD as dolichocephalic because it has an CepI less than 100, where the longitudinal diameters of the head prevail over the transverse diameters. This is similar to that reported in donkeys from Ecuador and Cuba (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015; Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016b), although this estimate in these animals was higher (29.0 and 31.9, respectively).

Table 4 Descriptive statistics of the ethnological and productive indices of the colombian creole donkeys (CCD) of the five natural subregions from department of Sucre.

a,b,c Different letters in the same line indicate statistically different averages between subregions (p <0.05). SD: standard deviation. Min: minimum. Max: maximum. CV: coefficient of variation.GM: Golfo de Morrosquillo. MM: Montes de María. MO: Mojana. SJ: San Jorge. SA: Sabanas. SD: standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variation. Min: minimum. Max: maximum. CI: corporal index. ThI: thoracic index. ILIsI: ilio-ischial index. ComI: compactness index. PelI: pelvic index. CepI: cephalic index. ProI: proportionality index. ReDeI: relative depth index. PoFI: posterior foot index. FrLI: firewood load index. DaThI: dactyl-thoracic index.

The productive indices: posterior foot index (PoFI), firewood load index (FrLI), and dactyl-thoracic index (DaThI) did not vary significantly between subregions (p >0.05). On the other hand, the proportionality index (ProI) was higher in the MO subregion and the relative depth index (ReDeI) in the donkeys of the GM region (Table 4). The ReDeI indicates a CCD with good proportionality and aptitude for work (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015), although the value obtained was less than 50. The above is correlated with motor aptitude or drag of large masses, determined by the firewood load index, which in this case shows an animal with strong limbs with good towing and carrying capacity. The PoFI is considered ideal when it is equal to 33, in this work the value obtained was higher, showing animals with a low rump. The DaThI also called the metacarpal-thoracic index is an indicator of the size of the animal (small, medium, or large) since it determines the relationship between the mass of the individual and the limbs that support it. In this sense, the CCD can be considered as hypermetric or heavy, this also indicates that it has larger members than necessary. As hypermetric, the donkeys of Ecuador (Jumbo Benítez et al. 2015), Romagnolo 11.9 ± 0.9 (Beretti et al. 2005) and the Tuscany region of 13.1 ± 1.0 (Sargentini et al. 2009) are also categorized, while the Cuban donkeys are more of the hypometric or ellipometric type (Fonseca Jiménez et al. 2016b).

In conclusion, the CCD has high morphological variability, as it does not present a defined zootechnical aptitude, its genetic improvement can be directed according to the needs of the producer, this could not only include loading and dragging but also onotherapy. Likewise, the CCD can be classified as longilinear, hypermetric, dolichocephalic, and concavilinear, proportionate, with good poise and aptitude for work.