1. Introduction

The transition toward Society 5.0 has introduced a paradigm shift in which technology and humanism converge to create organizational environments centered on holistic well-being, resilience, and personal fulfillment (Tavares et al., 2022). In this new work ecosystem, adaptability, emotional health, and passion for work emerge as essential competencies for facing a world characterized by uncertainty and constant disruption (Hamedani et al., 2024). Under this logic, organizations are no longer expected to be merely productive, but also emotionally sustainable, capable of learning, reinventing themselves, and preserving the human sense of work amid recurring crises and accelerated digital transformations (Palmucci et al., 2025). In this context, identifying psychological and organizational mechanisms that foster sustainable engagement and emotional resilience has become a matter of growing relevance, not only to improve productivity, but to protect mental well-being and social cohesion within rapidly evolving work environments (Salazar-Altamirano et al., 2024).

In line with the principles of SDG 8 from the 2030 Agenda, which promotes decent work and sustainable economic growth, emphasis on understanding the evolving dynamics of modern workplaces has increased (Kreinin and Aigner, 2021). In this context, there is more interest in researching the psychosocial factors that directly influence organizational health and collective well-being (Salazar-Altamirano et al., 2025). This growing attention has led to a renewed focus on organizational resilience as a transversal competency that permeates structures and internal dynamics (Mercader et al., 2021). This competency becomes especially relevant in organizational cultures facing disruption and ongoing change (Pradana and Ekowati, 2024). At the same time, passion for work is positioned as a driving force for professional engagement, particularly in contexts where pressure, complexity, and the need for meaning intensify (Zhang et al., 2022). In this regard, Salas-Vallina et al. (2021) warn that, although both constructs have strong theoretical development, research integrating them remains scarce and fragmented.

From this perspective, some theoretical approaches have explored the nuances of work passion, noting that not all its manifestations lead to positive outcomes (Vallerand, 2015). Authors such as Astakhova (2015) argue that its expression may fluctuate between more harmonious forms and others that are more rigid or compulsive, whose emotional and behavioral implications are not always functional in organizational settings. Similarly, recent studies like Zhang et al. (2022) have broken down resilience into components that respond to different levels of psychological experience, such as the emotional dimension, linked to affective regulation, and the adaptive dimension, related to active responses to contextual transformation. Although significant progress has been made, ambiguity still surrounds the way certain dimensions interact within organizational contexts (Camacho and Horta, 2022). This persistent uncertainty represents an important area of opportunity for academic research (Odeh et al., 2021).

Despite the growing recognition of these concepts, current literature reveals aspects that remain underexplored. On the one hand, there are few studies analyzing the direct relationship between organizational resilience and passion for work within the same conceptual model (Teng et al., 2024). While links between organizational resilience and its emotional and adaptive components have not been sufficiently explored (Galván-Vela et al., 2021), there is also limited understanding of how these specific forms of resilience might enhance or moderate work passion (Hillmann and Guenther, 2020). On the other hand, the distinction between harmonious and obsessive passion remains a largely unexplored area in terms of organizational impact, despite warnings about their nonlinear and context-dependent effects (Hochwarter et al., 2022).

Based on these premises, this study aims to explore the effect of organizational resilience and work passion, as well as the relationship between organizational resilience and its emotional and adaptive components, and between work passion and its subtypes: obsessive and harmonious. This theoretical proposal integrates variables that have previously been studied in isolation but, together, could offer an explanatory framework for understanding well-being and performance in complex work contexts.

To achieve this objective, the structure of the article is divided into six sections: first, the theoretical framework for the six variables is presented; second, the research methodology is described; third, results are presented; fourth, conclusions and discussions; fifth, practical, theoretical, and social implications are addressed; finally, the article concludes with limitations and recommendations for future research aimed at building resilient and emotionally sustainable work cultures.

2. Theoretical framework

2.7 Organizational resilience

Although today organizational resilience is conceived as a strategic capacity to face turbulent environments, it has its roots in the study of living systems, from where it was transferred to organizational theory in the second half of the 20th century (Folke, 2006). However, it is in the last two decades, especially following global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when it emerged as a strategic element within the analytical framework of organizational behavior under pressure (Napier et al., 2023). Its conceptualization has evolved from a static and defensive notion to one that recognizes resilience as a dynamic and adaptable capacity (Barrón-Torres and Sánchez-Limón, 2022). This shift emphasizes continuous adaptation and transformative learning in the face of adversity (Mokline and Abdallah, 2021).

From a contemporary perspective, organizational resilience has been understood as a multifactorial capacity that integrates anticipatory processes and containment mechanisms to address potential disruptions (Neri et al., 2025). In addition, it encompasses adaptive competencies aimed at preserving the structural, functional, and human integrity of the organization (Williams et al., 2017). As highlighted by Wang et al. (2024), this capacity is shaped through two domains: organizational planning and adaptability to disruptive contexts, the latter being the most decisive for sustaining team commitment and learning. Therefore, resilience transcends the operational realm and becomes interwoven with organizational culture, collective identity, and the ways in which organizations narrate, process, and reinterpret their critical experiences (Lee, 2024).

Considering these precedents, the growing relevance of this variable is justified by its direct effect on sustainability, performance, and organizational innovation capacity (Garrido-Moreno et al., 2024). In academic terms, Jiang et al. (2024) demonstrated, through a bibliometric analysis of over 340 studies, that organizational resilience has shifted from being a peripheral concept to becoming a connector for transdisciplinary research, especially in the field of management and organizational psychology.

Regarding work passion, the study by Teng et al. (2024) conducted in Taiwan with 471 employees in the restaurant sector showed that organizational resilience has a positive effect on work passion (both harmonious and obsessive). In contrast, research by Hochwarter et al. (2022), based on three independent samples in the United States (N = 175, 141, and 164), showed that high levels of work passion do not always lead to positive outcomes unless accompanied by strong personal resilience, suggesting that passion alone can become dysfunctional in vulnerable organizational contexts.

Regarding the link between organizational resilience and adaptive resilience, a recent study by Wang et al. (2024) in China with 175 primary care nurses revealed that organizational adaptive capacity is significantly associated with indicators of psychological safety, professional commitment, and self-directed learning, but not with emotional well-being. However, the research by Leite et al. (2023) in Brazil, based on a case study in a family-run food company, identified a stronger relationship between organizational resilience and adaptability only when an active socioemotional foundation was present, thus questioning its universality.

Concerning emotional resilience, Unjai et al. (2024) presented a systematic review of 33 studies in healthcare contexts, concluding that interventions designed to strengthen resilience, especially those based on mindfulness and professional coaching, produce significant improvements in workers' emotional stability. Nevertheless, Rahimi et al. (2023), in an experimental study with working university students in Canada (N = 320), found that obsessive passion, even in the presence of emotional resilience, does not always contribute to effective recovery from failure, thus raising questions about the nonlinear interaction of these variables. Although an integrative model that simultaneously articulates the six variables considered here has not yet been identified, reviewed findings support the urgent need to develop complex conceptual frameworks that explore their interactions. Integrating organizational resilience with emotional, adaptive, and motivational components could represent a theoretical opportunity and a path toward designing more human, flexible, and sustainable organizations in an increasingly uncertain world.

2.7.7 Emotional resilience

Emotional resilience refers to a person's ability to regulate their emotions, adapt to adversity, and effectively recover from stress or work-related pressure (Pahwa and Khan, 2022). In organizational contexts, this dimension is highly relevant for maintaining employees' psychological well-being and mitigating the effects of emotional exhaustion, especially in high-demand environments or prolonged uncertainty (Peng et al., 2022). Research on this topic is particularly significant due to its impact on individual mental health and its contribution to organizational functioning, since emotionally resilient employees tend to maintain positive attitudes, commitment, and performance even in adverse situations (Flynn et al., 2021).

As a dimension of organizational resilience, emotional resilience allows for an understanding of how individuals' internal resources interact with contextual factors to sustain emotional stability and responsiveness during crises (Troy et al., 2022). Additionally, high levels of emotional intelligence and organizational cultures that promote learning have been shown to strengthen this form of resilience by facilitating continuous adaptation in times of change (Ji, 2020).

Moreover, this dimension has been the subject of studies analyzing its relationship with adaptive resilience and showing both synergies and limitations. For example, Wang and Chiu (2024), in a study with 800 foreign professors at universities in Tier 1 cities in China, demonstrated that emotional intelligence, as a basis for emotional resilience, significantly influences individuals' adaptive performance. This relationship is mediated by psychological resilience, reinforcing the instrumental role of emotional resilience in complex professional adaptation processes. However, Han et al. (2023), in an analysis of 314 employees in China during the pandemic, observed that although emotional resilience (measured through emotional intelligence) can alleviate emotional exhaustion, it does not always translate into greater adaptive resilience when organizational practices do not sufficiently promote learning and autonomy. Therefore, its effect may depend on the organizational environment.

2.7.2. Adaptive resilience

Adaptive resilience has been consolidated as a theoretical and practical foundation for strengthening organizational resilience in times of crisis, as it allows organizations not only to withstand disruption but also to transform because of it (Miceli et al., 2021). This approach emphasizes the capacity for continuous learning, structural redesign, and dynamic adjustment in the face of unexpected challenges (Vargas-Hernández, 2022). In the academic field, its study has gained increasing prominence as a response to the limitations of traditional models focused solely on resistance or recovery (Yu et al., 2022). Adaptive resilience offers an evolutionary perspective on organizational change, aligning with emerging approaches on dynamic capability, adaptive leadership, and strategic transformation (Quansah et al., 2022). This position is as a central analytical category in current research on sustainability, change management, and performance under prolonged disruptive conditions (Singh and Modgil, 2024).

2.2 Work passion

Academic interest in work passion has increased since the early twenty-first century, mainly driven by the dualistic model proposed by Vallerand (2015), which introduced a more nuanced and precise interpretation of how people connect emotionally and motivationally with their work. This line of research emerged in response to the traditional approach to work motivation, recognizing that intense dedication to work does not always lead to benefits, but may produce ambivalent effects depending on the type of passion involved (Toth et al., 2021).

Theoretically, work passion is conceived as a strong inclination toward work, regarded as meaningful and integrated into the individual's identity (Mehmood et al., 2022). Under the dualistic model, two forms are distinguished: harmonious passion, which allows individuals to engage freely with their work while maintaining balance with other areas of life; and obsessive passion, which arises from internal pressure that compels individuals to work compulsively, even when it may generate conflict or distress (Bélanger and Ratelle, 2020). These dimensions will be discussed in detail later. According to Gillet et al. (2022), both forms have distinct psychological and organizational implications, and understanding this phenomenon is essential for promoting healthy and sustainable work environments.

Currently, its study is relevant both academically and practically. In academia, it is considered a strategic variable for understanding phenomena such as engagement, well-being, job satisfaction, and performance (Yukhymenko-Lescroart and Sharma, 2020). In practice, understanding how work passion manifests can help design organizational interventions aimed at developing more human and resilient workplace cultures (Salas-Vallina et al., 2021). Furthermore, its growing association with other psychosocial variables such as resilience, burnout, or engagement reinforces its centrality as an object of interdisciplinary study (Al-Dossary et al., 2024).

Regarding obsessive passion, Amarnani et al. (2020) conducted a study with 139 employees in the corporate sector in the Philippines, finding that this form of passion can lead to emotional exhaustion, especially when individuals lack professional adaptation resources. In contrast, in China, Astakhova et al. (2022) identified that obsessive passion does not always have negative effects. In their study with 193 employees, they found that this form of passion was positively related to occupational commitment in high-demand contexts, questioning the traditionally dysfunctional view of this dimension.

As for harmonious passion, Sudjadi and Indyastuti (2023) conducted a study in Indonesia with 236 working women and found that it is positively associated with self-efficacy and entrepreneurial curiosity, demonstrating its potential as a catalyst for economic empowerment. However, Benítez et al. (2023), in a study with 748 service sector employees in southern Spain, found that although harmonious passion can mitigate the negative effects of physical exhaustion on job satisfaction, its impact is not uniform. Workers with high harmonious passion reported greater satisfaction even under intense fatigue, but the benefits diminished in contexts of prolonged emotional exhaustion, suggesting that this form of passion is not always sufficient to neutralize accumulated psychological strain.

2.2.7 Harmonious passion

Harmonious passion, as a dimension of the affective bond with work, is expressed when work activity is internalized in an autonomous and balanced way, allowing the individual to experience a deep connection with their job without it negatively interfering with other areas of their life (Santos et al., 2023). This form of passion drives commitment, creativity, and promotes psychological well-being by fostering a flexible, sustainable, and self-regulated relationship with the professional environment (Yen et al., 2023). In today's global context, where high performance is demanded without compromising mental health, its study becomes essential to reconsider the conditions that make healthy intrinsic motivation possible (Benitez et al., 2023). From an academic perspective, addressing this dimension allows progress toward more human-centered productivity models, in which balance between achievement and well-being is not conceived as a contradiction, but as an attainable goal (Jiang, 2024).

The contrast between harmonious and obsessive passion remains the subject of study to understand emotional engagement in work environments. In a longitudinal study with 622 nurses in France, Cheyroux et al. (2024) found that trajectories dominated by harmonious passion were associated with better levels of psychological health, performance, and lower absenteeism, while those with predominant obsessive passion were linked to greater fatigue, turnover intentions, and presenteeism, reinforcing the idea that not all forms of passion are equally functional over time or in relation to each other. However, in an Australian study with 249 full-time employees, Tolentino et al. (2022) found that obsessive passion did not produce significant negative effects on performance or job satisfaction, nor in relation to harmonious passion, thus suggesting that in certain contexts, this form of passion can be channeled toward acceptable outcomes if accompanied by protective psychological resources.

2.2.2 Obsessive passion

Obsessive passion represents an intense but dysregulated form of work involvement, characterized by controlled internalization that leads the individual to feel an internal pressure to perform, even when this conflicts with other areas of their life (Liao et al., 2022). Its study has gained increasing relevance both in organizational settings and in academia, as it helps explain why highly committed workers may experience burnout, work-life conflict, and a decline in well-being, despite displaying high levels of productivity (Sigmundsson and Elnes, 2024). In an era that exalts passion as a professional virtue, ignoring its dysfunctional forms may perpetuate workplace cultures where excessive devotion is normalized and even rewarded (Rai et al., 2024).

2.3 Contribution to the Dualistic Model of Passion (DMP)

The present research is theoretically grounded in the Dualistic Model of Passion (DMP) proposed by Vallerand (2015), which distinguishes between harmonious and obsessive passion as two divergent forms of affective involvement with meaningful activities. This theory has proven robust in explaining both adaptive and dysfunctional outcomes in work, educational, and personal contexts. However, recent studies point to the need to expand this framework toward more complex dimensions of the organizational environment, such as emotional, adaptive, and organizational resilience. These variables could significantly interact with the forms of passion and modulate their effects (Slemp et al., 2020). The model proposed in this study seeks, precisely, to contribute to that conceptual expansion by integrating dual work passion with multiscale resilience constructs and analyze their combined influence on well-being and performance in high-pressure environments. By articulating these variables, the purpose is to empirically validate new relationships and generate useful knowledge for designing intervention strategies that promote sustainable passion and comprehensive resilience within contemporary organizations.

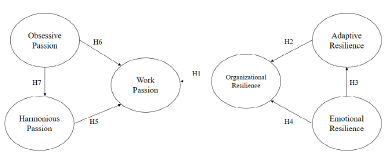

Considering the theoretical body reviewed, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Organizational resilience has a positive and significant effect on work passion.

H2: Adaptive resilience has a positive and significant effect on organizational resilience.

H3: Emotional resilience has a positive and significant effect on adaptive resilience.

H4: Emotional resilience has a positive and significant effect on organizational resilience.

H5: Harmonious passion has a positive and significant effect on work passion.

H6: Obsessive passion has a positive and significant effect on work passion.

H7: Obsessive passion has a positive and significant effect on harmonious passion.

These hypotheses define the model proposed in Figure 1:

3. Methodology

3.1 Participants and procedures

This study was conducted using a quantitative approach, with a non-experimental and cross-sectional design, because variables were observed as naturally occurred in their context, without intentional manipulation by researchers (Creswell, 1994). This design allowed us to examine the relationships among analyzed variables at a single point in time, facilitating the collection of empirical evidence to validate the proposed theoretical model. Data were collected through a self-administered electronic questionnaire, distributed anonymously among university graduates from various professional fields in the state of Baja California, Mexico, using contact networks and digital media. Before answering the questionnaire, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the confidentiality of their responses was guaranteed, and explicit informed consent was requested.

To control common method bias (CMB), various strategies were adopted, such as ensuring anonymity, formulating neutral items, and avoiding biased wording. Additionally, Harman's single-factor test was applied, concluding that no dominant dimension explained most of the variance, which indicates that CMB does not pose a significant threat (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The sample consisted of 411 participants (see Table 1) selected through non-probability purposive sampling. This technique is appropriate in studies where random access to the population is limited (Etikan, 2016), especially when a specific demographic or occupational profile is required. A screening question was applied to include only individuals with formal work experience, who had worked for at least six months in their current position.

According to the demographic data, 60.1% of the participants were men and 39.9% were women. Regarding nationality, 91.6% were Mexican, while the rest came from countries such as the United States, Colombia, Germany, Spain, and Paraguay. As for educational attainment, 74.7% held a bachelor's degree, 22.2% a master's degree, and 3.1% a doctorate. In relation to work experience, 49.6% worked in the industrial sector, 20% in services, 15.1% in the public sector, 10.7% in the commercial sector, and 4.6% in the primary sector. Organizational size was also diverse: 50.7% worked in companies with more than 500 employees, 15.1% in medium-sized companies (51 to 250), 13.1% in small companies (11 to 50), 10.2% in micro-enterprises (1 to 10), and 10.9% in large companies with up to 500 employees. Regarding the legal nature of the organization, 76.4% belonged to private companies, 16.8% to the public sector, 2.7% to non-profit associations, and 4.1% were independent workers.

Table 1 Sociodemographic profile of participants

| Variable | Options | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male Female | 247 164 | 60.10% 39.90% |

| Mexico | 376 | 91.60% | |

| Nationality | United States Others (Colombia, Germany, Spain, Paraguay) | 29 6 | 7.10% 1.30% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 307 | 74.70% | |

| Educational attainment | Master’s degree | 91 | 22.20% |

| Doctorate | 13 | 3.10% | |

| ≤ 5 years | 98 | 23.80% | |

| 5 - <10 years | 106 | 25.80% | |

| 10 - <15 years | 79 | 19.20% | |

| Work experience | 15 - <20 years | 31 | 7.50% |

| 20 - <25 years | 52 | 12.70% | |

| 25 - <30 years | 28 | 6.80% | |

| ≥ 30 years | 15 | 3.70% | |

| Primary | 19 | 4.60% | |

| Industrial | 204 | 49.60% | |

| Economic sector | Commercial | 44 | 10.70% |

| Services | 82 | 20.00% | |

| Public | 62 | 15.10% | |

| Microenterprise (1-10 employees) | 42 | 10.20% | |

| Small (11-50 employees) | 54 | 13.10% | |

| Company size | Medium (51-250 employees) | 62 | 15.10% |

| Large (251-500 employees) | 45 | 10.90% | |

| Very large (>500 employees) | 208 | 50.70% | |

| Private | 314 | 76.40% | |

| Legal nature | Public Non-profit organization | 69 11 | 16.80% 2.70% |

| Independent | 17 | 4.10% | |

| Variable | Value range | Mean (estimated) | SD (estimated) |

| Age (years) | 18 to 70 years | 44 | 15.01 |

Source: own elaboration

3.2 Instruments

The data collection instrument consisted of a structured digital questionnaire designed to assess the main variables of the model; that is, work passion and organizational resilience, along with their respective dimensions. It was administered through electronic devices with internet access. The work passion variable was measured using the scale developed by Cid et al. (2019), based on Vallerand's (2015) dualistic model of passion. This scale includes 15 items distributed across three subdimensions: general passion (3 items), harmonious passion (4 items), and obsessive passion (8 items), with examples such as: "This activity is in harmony with other activities in my life" and "I feel an almost obsessive need to engage in this activity."

Regarding organizational resilience, a scale composed of 10 items was used, five of which were taken from Bustinza et al. (2016), and the other five were developed by the authors of this study. This variable was structured into three dimensions: organizational resilience (3 items), adaptive resilience (4 items), and emotional resilience (3 items), including statements such as: "Problems are assumed as challenges and opportunities to learn." All items were assessed using a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 = "Strongly disagree" and 7 = "Strongly agree," allowing for appropriate response discrimination. The five items created by the authors, including their theoretical justification and content validation procedures, are detailed in sub-section 3.2.1. For reference, the complete list of items is available in Appendix 1.

3.2.7 Content validation of author-developed items

The five items developed by the authors to complement the organizational resilience scale were designed to address specific behavioral and cultural aspects of resilience that were not fully captured by the original scale of Bustinza et al. (2016). These new items aimed to reflect current organizational challenges under the Society 5.0 paradigm, including collective problem-solving, proactive learning, and emotional adaptability in highly digitized and disruptive environments.

To ensure the content validity of these items, a systematic review was carried out. First, the theoretical dimensions of resilience proposed by Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011) and Duchek (2020) were reviewed to align item content with established conceptual frameworks. Based on them, preliminary items were formulated and submitted for expert evaluation.

Following the recommendations of Rubio et al. (2003), a panel of eight academic and professional experts in organizational psychology and human resource management independently assessed relevance, clarity, and representativeness of each item. Experts were selected based on their publication record and professional experience in resilience-related research.

Content validity was quantified using the Content Validity Index (CVI), as proposed by Lynn (1986), which requires at least 0.78 for each item to be retained. All five items exceeded this threshold. In addition, the Aiken's V coefficient was calculated to evaluate inter-rater agreement (Aiken, 1985). It yielded satisfactory values above 0.80, thus confirming strong content agreement among evaluators.

The wording of the items was revised based on expert feedback to improve conceptual clarity and ensure cultural adaptation to the Latin American work context. Although the psychometric properties of the scale were tested through convergent and discriminant validity (see Section 4), future research is encouraged to conduct additional confirmatory factor analyses in diverse samples and organizational sectors. This content validation process aligns with established best practices in scale development and ensures that new items are theoretically grounded and contextually relevant for studying resilience in contemporary organizational settings.

3.3 Data analysis technique

For data analysis, the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique was employed using SmartPLS 4.0 software, which applies the partial least squares approach (PLS-SEM) (Hair et al., 2021). This methodology is widely recognized for its ability to estimate complex models with multiple latent variables and simultaneous relationships, even with moderate sample sizes and without strict requirements of multivariate normality (Henseler et al., 2015).

Before conducting the structural analysis, an exploratory review of the database was carried out to detect outliers, extreme values, and missing data. Internal reliability of the constructs was ensured by calculating Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability (rho_c), following the recommended minimum threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2019). To assess convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) was considered, with acceptable values above 0.50. In addition, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was applied to verify discriminant validity by ensuring that the square root of the AVE for each construct exceeded its correlations with other constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

The validation of the structural model was carried out by evaluating the statistical significance of the path coefficients through the analysis of corresponding t and p values. Relationships were considered significant when t-values were equal to or greater than 1.96 and p-values were less than or equal to 0.05, in accordance with criteria established in the specialized literature (Hair et al., 2021). This procedure supported the validity of the hypothesized relationships in the model and ensured consistency between the empirical evidence and the proposed theoretical framework.

4. Results

4.7 Exploratory factor analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (see Table 2) was implemented with the aim of identifying the underlying structure of the evaluated constructs: work passion and organizational resilience, including their associated dimensions. The principal component method with Varimax rotation was used, following the methodological recommendations of Hair et al. (2019) and Kline (2015) due to their potential to optimize factor loading and facilitate interpretation.

Results revealed item correlations within each dimension ranging from 0.415 to 0.814, which reflects adequate internal cohesion among indicators. Communalities ranged between 0.639 and 0.880, indicating that the items explain a considerable proportion of the variance in their respective factors (Tabachnick et al., 2018). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy yielded values above 0.800 for all constructs except for organizational resilience. The minimum was 0.774 and the maximum 0.887, thus confirming excellent suitability for factor analysis (Field, 2017). Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant in all cases(p < 0.001), indicating significant correlations among the items. Likewise, the total variance explained by the factors ranged from 66.0% to 77.4%, exceeding the recommended minimum threshold of 60% for studies in social sciences (Kline, 2015). These results validate the internal structure of the scales used and support their relevance to measure the theoretical constructs proposed in the model.

Table 2 Exploratory factor analysis

| Variable | Item Correlations | Communalities | KMO | Bartlett's Test | Explained Variance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work passion | 0.512 - 0.807 | 0.663 - 0.880 | 0.854 | p = 0.000 | 77.40 |

| Harmonious passion | 0.702 - 0.780 | 0.690 - 0.793 | 0.832 | p = 0.000 | 71.20 |

| Obsessive passion | 0.596 - 0.753 | 0.639 - 0.788 | 0.887 | p = 0.000 | 73.10 |

| Organizational resilience | 0.415 - 0.497 | 0.665 - 0.775 | 0.800 | p = 0.000 | 66.00 |

| Adaptive resilience | 0.496 - 0.811 | 0.690 - 0.812 | 0.828 | p = 0.000 | 70.90 |

| Emotional resilience | 0.457 - 0.814 | 0.667 - 0.774 | 0.774 | p = 0.000 | 68.30 |

Source: own elaboration

4.2 Correlational analysis

Next, a bivariate correlation analysis was performed (see Table 3) to examine the associations among the main variables of the model: obsessive passion, harmonious passion, work passion, emotional resilience, adaptive resilience, and organizational resilience. All correlations were positive and statistically significant (p < 0.01), supporting the theoretical consistency of the proposed model.

Table 3 Bivariate Correlations

| Variables | Obsessive Passion | Harmonious Passion | Work Passion | Emotional Resilience | Adaptive Resilience | Organizational Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obsessive Passion | 1 | 0.596** | 0.512** | 0.254** | 0.244** | 0.223** |

| Harmonious Passion | - | 1 | 0.807** | 0.457** | 0.496** | 0.415** |

| Work Passion | - | - | 1 | 0.475** | 0.497** | 0.424** |

| Emotional Resilience | - | - | - | 1 | 0.814** | 0.735** |

| Adaptive Resilience | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.811** |

| Organizational Resilience | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

Note: **p < 0.01.

Source: own elaboration

Harmonious passion showed a strong correlation with work passion (r = 0.807). This indicates that it plays a key role in positive work experience. Likewise, obsessive passion was moderately correlated with harmonious passion (r = 0.596), thus suggesting a possible influence between both forms of passion. However, obsessive passion showed a weaker correlation with work passion (r = 0.512), which aligns with findings that warn about the ambivalent effects of this dimension. Regarding resilience, emotional resilience was strongly correlated with adaptive resilience (r = 0.814), and the latter also showed a strong correlation with organizational resilience (r = 0.811). Additionally, emotional resilience had a moderate correlation with organizational resilience (r = 0.735); therefore, its influence may be indirect. Finally, organizational resilience showed a positive, although lower, correlation with work passion (r = 0.424), reflecting a significant but less intense relationship than other associations in the model.

4.3 Causal relationship analysis

4.3.7 Convergent and discriminant validity

To ensure the quality of the measurements used in the structural model, convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs were evaluated. For convergent validity, Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated. All values obtained were within the ranges recommended in the literature (Hair et al., 2019), thus suggesting adequate internal consistency of the scales. Alpha coefficients ranged from 0.837 to 0.937, while composite reliability ranged from 0.831 to 0.938. In turn, AVE values exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.50, ranging from 0.551 to 0.703. These results support that the indicators used consistently and adequately represent the latent constructs proposed in the model. Detailed values are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 Convergent validity

| Construct | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Resilience | 0.837 | 0.831 | 0.551 |

| Adaptive Resilience | 0.854 | 0.861 | 0.556 |

| Organizational Resilience | 0.912 | 0.91 | 0.716 |

| Harmonious Passion | 0.927 | 0.927 | 0.709 |

| Obsessive Passion | 0.922 | 0.923 | 0.626 |

| Work Passion | 0.937 | 0.938 | 0.703 |

Source: own elaboration

Regarding discriminant validity, the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) were used. According to the first criterion, the square root of the AVE of each construct was greater than the shared correlations with other constructs. This confirms the conceptual distinction between them. Likewise, all HTMT values were below the recommended threshold of 0.90 suggested by Henseler et al. (2015); therefore, it proves independence among the measured constructs. Table 5 presents these results.

Table 5 Discriminant validity

| Construct | HTMT < 0.90 (max.) | √AVE > correlations (Fornell-Larcker) |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Resilience | 0.648 | 0.742 |

| Adaptive Resilience | 0.751 | 0.746 |

| Organizational Resilience | 0.797 | 0.846 |

| Harmonious Passion | 0.743 | 0.842 |

| Obsessive Passion | 0.848 | 0.791 |

| Work Passion | 0.808 | 0.838 |

Source: own elaboration

4.3.2 Structural model fit indicators

Multiple fit indicators were examined to validate the adequacy of the proposed structural model. They were grouped into three categories: absolute fit, incremental fit, and parsimony. The Chi-square statistic (CMIN) value was 614 with p = 0.001, which indicates marginal fit due to its sensitivity to sample size. However, other indices such as RMSEA (0.069) and SRMR (0.043) remained within acceptable ranges; thus, adequate absolute fit was confirmed (Hu and Bentler, 1999). Regarding incremental fit, results for CFI (0.954), IFI (0.954), and TLI (0.947) greatly exceeded the 0.90 threshold, reflecting a robust model consistent with the proposed theoretical structure (Hair et al., 2019). Finally, parsimony indicators also supported the model's efficiency. The CMIN/DF ratio was 3.02, considered acceptable, while the PGFI index reached a value of 0.719, within the optimal range (Byrne, 2016; Kline, 2015). Taken together, these results indicate that the proposed structural model shows solid and reliable fit. Table 6 summarizes these findings.

4.4 Evaluation of structural hypotheses

To empirically evaluate the proposed relationships in the structural model, hypothesis testing was carried out using the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique. It enables simultaneous analysis of direct effects between the model's latent variables, considering both the statistical significance and the magnitude of the standardized coefficients (ß). Table 7 shows results obtained for each of the seven proposed hypotheses.

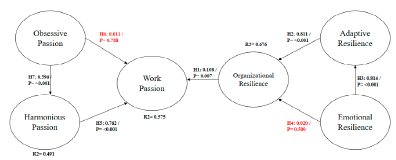

Findings reveal that H1 was confirmed (ß = 0.108, p = 0.007), i.e., organizational resilience has a positive and significant effect on work passion. In H2, a highly significant direct impact of adaptive resilience on organizational resilience was observed (ß = 0.811, p < 0.001). H3 was also confirmed, showing a positive effect of emotional resilience on adaptive resilience (ß = 0.814, p < 0.001). However, H4 was rejected (ß = 0.020, p = 0.500), suggesting that emotional resilience does not have a significant direct effect on organizational resilience. Regarding the dimensions of work passion, H5 was confirmed (ß = 0.762, p < 0.001), demonstrating that harmonious passion positively influences work passion. In contrast, H6 was rejected (ß = 0.011, p = 0.788), as obsessive passion did not have a significant effect on work passion. Finally, H7 was confirmed (ß = 0.596, p < 0.001), establishing that obsessive passion has a positive effect on harmonious passion.

Figure 2 presents the final estimated structural model and shows the direct relationship among study variables: emotional resilience, adaptive resilience, organizational resilience, harmonious passion, obsessive passion, and work passion. The empirically validated paths are indicated by arrows accompanied by their respective standardized regression coefficients (ß) and statistical significance levels (p). Additionally, R2 values for the endogenous variables are reported, thus enabling an assessment of the degree of variance explained by their respective predictors.

Results show that the model explains 67.6% of the variance in organizational resilience (R2 = 0.676), which is considered high according to the criteria of Hair et al. (2019). Similarly, 57.5% of the variance in work passion (R2 = 0.575) is explained by the combination of harmonious and obsessive passion, representing a moderately high explanatory capacity. In the case of adaptive resilience, R2 = 0.664 was obtained, confirming that emotional resilience is a strong predictor of this dimension. Meanwhile, harmonious and obsessive passion explain 49.1% of the variance between them (R2 = 0.491), which is also interpreted as a moderate level. Based on the cutoff points proposed by Hoyle (2022), R2 values above 0.67 are considered high; between 0.33 and 0.67, moderate; and below 0.33, low. In this sense, the model demonstrates robust explanatory capacity in core variables such as organizational resilience, adaptive resilience, and work passion, and confirms the relevance of the proposed theoretical framework and the structural consistency of the modeled relationships.

Table 6 Structural model fit indicators

| Fit Type | Measure | Acceptable Level | Model Result | Acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN | CMIN ≈ 2 x df | 614 | Acceptable | |

| Absolute | p-value | > 0.05 | 0.001 | Marginal |

| SRMR | < 0.08 | 0.043 | Acceptable | |

| RMSEA | < 0.08 | 0.069 | Acceptable | |

| CFI | > 0.90 | 0.954 | Acceptable | |

| Incremental | IFI | > 0.90 | 0.954 | Acceptable |

| TLI | > 0.90 | 0.947 | Acceptable | |

| Parsimony | CMIN/DF PGFI | < 5 0.50 - 0.80 | 3.020 0.719 | Acceptable Acceptable |

Source: own elaboration

Table 7 Hypothesis testing

| Hypothesis | Relationship | ß | S.E. | C.R. (t) | p-value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Organizational Resilience → Work Passion | 0.108 | 0.040 | 2.692 | 0.007 | Confirmed |

| H2 | Adaptive Resilience → Organizational Resilience | 0.811 | 0.019 | 41.814 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

| H3 | Emotional Resilience → Adaptive Resilience | 0.814 | 0.020 | 40.082 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

| H4 | Emotional Resilience → Organizational Resilience | 0.020 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.500 | Rejected |

| H5 | Harmonious Passion → Work Passion | 0.762 | 0.032 | 23.476 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

| H6 | Obsessive Passion → Work Passion | 0.011 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.788 | Rejected |

| H7 | Obsessive Passion → Harmonious Passion | 0.596 | 0.032 | 18.531 | 0.000 | Confirmed |

Source: own elaboration

5. Discussion

Results obtained in this study enable a deeper understanding of the relationships between work passion and organizational resilience and partially confirm the proposed theoretical model.

First, the positive and significant relationship between organizational resilience and work passion-Hypothesis 1-supports the notion that resilient environments can foster affective motivation among employees. However, the relatively low influence coefficient (ß = 0.108) suggests that this relationship might be mediated by other organizational variables, such as leadership or culture. Considering that over 50% of participants work in large organizations, this may reflect a certain detachment between resilient structures and the worker's subjective experience, an issue also discussed by Teng et al. (2024).

Second, the model strongly confirms the hierarchical structure between emotional, adaptive, and organizational resilience. The relationships between emotional and adaptive resilience- Hypothesis 3 (ß = 0.814)-, and between adaptive and organizational resilience- Hypothesis 2; (ß = 0.811)-, were highly significant. These results reinforce prior findings (Han et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022) that emotional self-regulation is a fundamental resource for effective adaptation in complex contexts. Our sample shows a wide range of work experience, which may indicate that adaptability increases with seniority, yet remains contingent on emotional competencies.

Third, the absence of a direct effect of emotional resilience on organizational resilience-Hypothesis 4- underscores the need for institutional structures that translate individual emotional capacities into collective responses. This is consistent with studies such as Han et al. (2023), who emphasize that emotional strengths must be organizationally mediated to generate impact.

Regarding motivation, harmonious passion had a strong and direct effect on work passion-Hypothesis 5 (ß = 0.762)-, supporting studies by Cheyroux et al. (2024) and Salas-Vallina et al. (2021). This implies that individuals who develop a balanced emotional bond with their work tend to have higher engagement and affective commitment. In contrast, obsessive passion was not directly related to work passion-Hypothesis 6-but did show a strong link to harmonious passion-Hypothesis 7 (ß = 0.596)-, suggesting a more complex interplay. As Tolentino et al. (2022) argue, obsessive passion can become functional when accompanied by psychological support and autonomy.

Together, these findings indicate that the variables studied do not operate in isolation but through interdependent networks influenced by personal, organizational, and contextual elements. This highlights the importance of examining passion and resilience from models capable of capturing their dynamic and systemic interactions.

6. Conclusions

This study offers a novel contribution to understanding psychological resources, especially resilience and work passion, interacting within complex and evolving organizational systems. The empirical model demonstrates that organizational resilience does not operate in isolation but is built through a sequential structure were emotional resilience fosters adaptability. In turn, this supports collective functioning. Similarly, harmonious passion emerged as a primary driver of sustained engagement, revealing the emotional underpinnings of professional motivation.

By integrating the Dualistic Model of Passion and multilevel resilience theory into a unified framework, the study provides an original analytical approach to exploring affective dynamics at work. This intersection allows for a more holistic comprehension of how individuals and organizations co-develop affective sustainability in response to contemporary challenges.

Moreover, the model proposed here responds to an emerging need in organizational psychology: to explain not only how people cope, but how they remain emotionally invested in environments of uncertainty and digital transformation. In doing so, it moves beyond descriptive analysis to offer a theoretical structure that can inform future empirical research and organizational design in the context of Society 5.0.

6.1 Practical, theoretical, and social implications

Results of this study offer relevant contributions that extend beyond the academic sphere into organizational and societal transformation, especially in the era of Society 5.0, which emphasizes the integration of technological advancement and human well-being. In this context, organizations are challenged to cultivate not only innovation and adaptability but also affective commitment and psychological sustainability among their members.

From a practical perspective, the validation of the positive relationship between organizational resilience and work passion highlights the importance of fostering environments that respond not only to adversity but also proactively build conditions for healthy and sustained emotional engagement. Given the increasing demands for employee well-being and meaning at work, these findings support the design of workplace cultures that prioritize trust, psychological safety, autonomy, and continuous learning.

Likewise, the finding that emotional resilience significantly impacts adaptive resilience, but not directly organizational resilience, points to an implication: emotional development programs must be complemented by institutional mechanisms that translate individual capabilities into collective responses. To this end, the implementation of emotional support systems, empathetic leadership, and horizontal decision-making structures is suggested, allowing personal emotional regulation to be channeled into adaptive organizational dynamics. Only then can sustainable organizational resilience be articulated without relying exclusively on individual effort.

At the theoretical level, the proposed model expands the frameworks of the Dualistic Model of Passion (Vallerand, 2015) by integrating it with resilience constructs at different levels of analysis. The empirical evidence obtained confirms that harmonious passion operates as a genuine driver of work engagement, while obsessive passion, although it does not have a direct effect on work passion, maintains a significant relationship with harmonious passion. This dynamic suggests a more fluid interaction between both forms of passion than originally proposed by the model, paving the way for a possible conceptual reconfiguration based on levels of intensity, coexistence, or contextual transitions between them.

From a social dimension, findings reinforce the urgency of moving toward more human and emotionally sustainable work models, especially in the post-pandemic era and under the challenges of Society 5.0. The promotion of balanced work passion, sustained by resilient and emotionally intelligent cultures, is configured as a strategy to reduce phenomena such as burnout, absenteeism, or work demotivation, which impact not only productivity but also the mental health of broad social sectors. In this regard, public policies, corporate wellness programs, and talent management practices must incorporate these findings to foster environments where commitment is not at odds with personal care or work-life balance.

6.2 Limitations and future research lines

Although this study provides valuable evidence on the relationships between work passion and organizational resilience, it is necessary to acknowledge limitations inherent to the design and scope of the work. First, the study is based on a quantitative cross-sectional approach, which prevents establishing causal relationships between the variables analyzed. While data allows for the identification of significant associations, future research could adopt longitudinal or mixed methodologies that capture the evolution of these relationships over time and across different organizational cycles.

Another limitation lies in the self-reported nature of the instruments used, which may be influenced by social desirability bias or subjective perception. It would be valuable to incorporate triangulated evaluations, such as environmental observations or assessments from leadership teams, to contrast individual experience with objective organizational dynamics. Likewise, although the model integrated psychosocial variables, it did not consider other relevant factors such as engagement, leadership, emotional climate, or contractual conditions, which could act as mediating or moderating variables in the observed relationships.

A specific methodological limitation concerns the inclusion of five items developed by the authors to assess organizational resilience. Although content validation was conducted with expert judges and psychometric indicators were satisfactory, the absence of prior use in peer-reviewed publications limits the comparability of this instrument with existing literature. Future studies are encouraged to subject these items to confirmatory analyses and validation processes in diverse contexts to strengthen their robustness and facilitate replication.

Regarding future research lines, it is proposed to explore the coexistence of harmonious and obsessive passion as dynamic profiles rather than rigidly opposed dimensions, which would allow for a more realistic understanding of emotional transitions in contemporary work experience. Similarly, it would be pertinent to investigate nonlinear or configurational models (e.g., cluster analysis or case-based modeling) that identify combinations of psychosocial variables generating differentiated organizational resilience profiles. Additionally, the analysis of indirect effects between the model's variables, especially those mediated by adaptive resilience or harmonious passion, could provide a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the observed relationships, opening new avenues for theoretical and applied development. It is also necessary to address how these variables behave in hybrid or digital work environments, especially in the post-pandemic context, where forms of work engagement, autonomy, and sense of belonging have been deeply transformed. Finally, it is recommended to expand the study to diverse international contexts, incorporating cultural analysis as a variable, given that the meanings of passion and resilience can vary substantially according to the social, economic, and organizational norms of each region.