Introduction

A well-preserved subfossil tree was discovered in Valle del Cauca, Colombia (Figure 1). The large tree trunk was found when drilling a well at a water treatment plant in Puerto Mallarino, Cali. The specimen exhibits remarkable preservation, with much of its original tissue still intact. This preservation is unusual, as most fossil samples are mineralized with silica or carbonates.

Subfossil wood can be found in surroundings that inhibit microbial decay and prevent exposure to oxygen and harsh chemicals. It can be mummified, retaining most of its original tissue; charcoalified due to combustion in an anaerobic environment, or coalified from intense heat and pressure during deep burial (Mustoe, 2018). Although most mummified wood localities are found in Quaternary volcanic settings, there are also Neogene and Paleogene records from the Canadian Arctic, northwestern United States, Hungary, Italy, China, and Japan, among other sites (Mustoe, 2018).

Figure 1 Large tree trunk found at a water treatment plant in Puerto Mallarino, Valle del Cauca, Colombia

These types of fossil fragments can be identified with similar methods to those used for modern wood preparation, where anatomical sections for microscopic observation are obtained with microtomes (Jagels et al., 2005). We propose that this non-mineralized wood belongs to the Lecythidaceae family, a pantropical group of trees within the order Ericales (APG IV, 2016). This family is most diverse in the Neotropics (Mori et al, 1990; Vargas & Dick, 2020) and consists of three subfamilies: Foetidioideae (Madagascar), Planchonioideae (Asia and Africa), and Lecythidoideae (Mori et al, 2017), the latter being the largest with approximately 232 species (Vargas & Dick, 2020).

The Lecythidoideae crown clade dates back 46 million years ago, with the stem age at 62.7 million years (Vargas & Dick, 2020) suggesting that the family dispersed well after the breakup of Gondwana, and most of its major clades diversified during the Miocene (23-5.3 million years ago). Vargas & Dick (2020) proposed the Guyana floristic region as the ancestral range for many Lecythidoideae clades.

After Lecythidoideae was established in the Neotropics, it diversified into a wide range of species potentially shaped by Pleistocene refugia (Haffer, 1969; Thomas et al, 2014); however, there is no comprehensive study on Lecythidoideaen diversification. The multiple fossil records of Lecythidaceae have been primarily described from fossil pollen and wood and most of them are from India. The oldest record is from the Piauí Cretaceous in Brazil (Table 1).

Today, the Valle del Cauca region is almost entirely deforested and dominated by sugar cane crops. Only four Lecythidaceae species have been identified in its tropical dry forest: Eschweilera caudiculata R. Knuth 1939, Gustavia speciosa (Kunth) DC 1828, Gustavia superba (Kunth) O. Berg 1856, and Lecythis minor Jacq. 1763 (Pizano et al, 2014; Silverstone-Sopkin, 2012).

Materials and methods

Geological setting

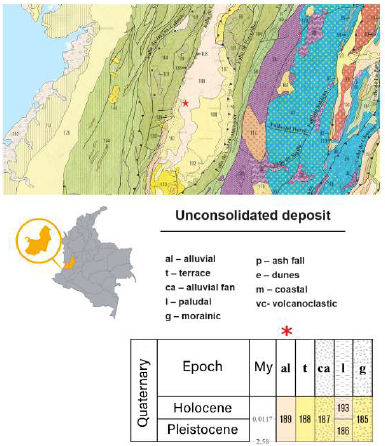

The fossil wood was collected at the Emcali Water Treatment Plant in Puerto Mallarino (Figure 2), near the Cauca River in Cali, department of Valle del Cauca, Colombia (3.4462 N; 76.4795 W at 1018 m.a.s.l.).

Figure 2 Sample collection site (red star) and stratigraphic column (red asterisk). Taken and modified from Gómez et al., 2023.

A three-meter-long tree trunk (Figure 1) was collected during the drilling of a 50-meter-deep water well at meter 17. In this area, Quaternary alluvial deposits are exposed (Gomez et aL, 2023), and probably the well crossed this particular one (Figure 2). The fossil was sliced into 20 pieces with a benchtop band saw at Universidad ICESI (Cali, Colombia). Five of these pieces were sent to Universidad EAFIT (Medellín, Colombia), where they were sectioned for anatomical observation. Another fragment was sent to the Beta Analytic Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory (Miami, Florida, United States) for radiocarbon dating (sample ID 48530), and the remaining pieces remained at the Universidad ICESI Herbarium.

Sample processing

The anatomical features were studied from small pieces of wood found at the collection site and later placed in Ziploc bags to keep them moist until the time of preparation in the laboratory. Some of the well-preserved wood samples had to be dehydrated by immersion in 95% ethanol for 72 hours and then embedded in polyethyleneglycol (PEG) 2000 at 60°C for 24 hours. Then, we obtained 20-70 um thick slices using a SLEE Mainz Rotary Microtome CUT 5062. The best-quality slices from each sample were immediately assembled using Eukitt to prevent the tissue from degrading.

We used the terminology from the IAWA Hardwood List (Wheeler, 1986; IAWA Committee, 1989) for the descriptions, and determined affinities by consulting the literature (de Zeeuw & Mori, 1987; Detienne & Jacquet, 1983; Diehl, 1935; Metcalfe & Chalk, 1950; Richter, 1982) and the multiple-entry key InsideWood from the Inside Wood Database (2004 onwards) (Wheeler, 2011). Photographs were taken with an Olympus BX53 light microscope and an SC100 digital camera with a 10.5 MP CMOS sensor.

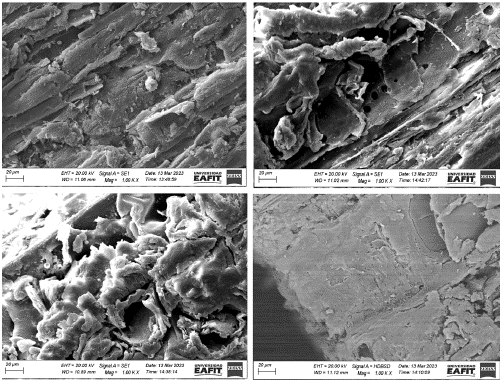

We scanned the sample with a Scanning Electron Microscope to assess the type of non-mineralization (mummification, charcoalification, or coalification) and the potential for stable isotope analyses (Mustoe, 2018: Figure 3). For the taxonomic classification, we followed APG IV (The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, 2016).

Results

Radiometric dating

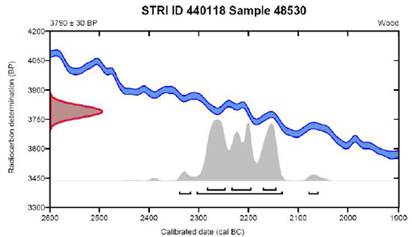

The radiocarbon dating of sample 48530 indicated a calibrated age of 4255 - 4083 cal BP (91.5%) (Beta Analytic 632015, Conventional Radiocarbon Age: 3790 ± 30 BP, percent modern carbon (pMC): 62.39 ± 0.23 pMC, δ13C (IRMS): -25.3%%) (Figure 4).

Figure 3 SEM photos. The wood's external structure remains largely preserved. The cell walls consist of an outer primary wall that encases a multi-layered secondary wall. The primary wall, which can be relatively thick, is primarily made up of cellulose and hemicellulose. In contrast, the thinner secondary wall is predominantly composed of cellulose and lignin. This secondary wall is typically divided into three distinct layers (lamellae), each varying in the arrangement of cellulose aggregates and the amount of lignin.

Systematic palaeontology

Order - Ericales

Family - Lecythidaceae

Subfamily - Lecythidoideae Beilschmied

Clade - Bertholletia

Genus - Eschweilera/Lecythis

Age -calibrated age of 4255 - 4083 cal BP (radiocarbon dating analysis obtained for the fossil fragment)

Description in IAWA feature numbers: 5p 13p 22p 26p 32p 56p 65p 66p 70p 87p 89p 97p 106p 115p with 1 allowable mismatch

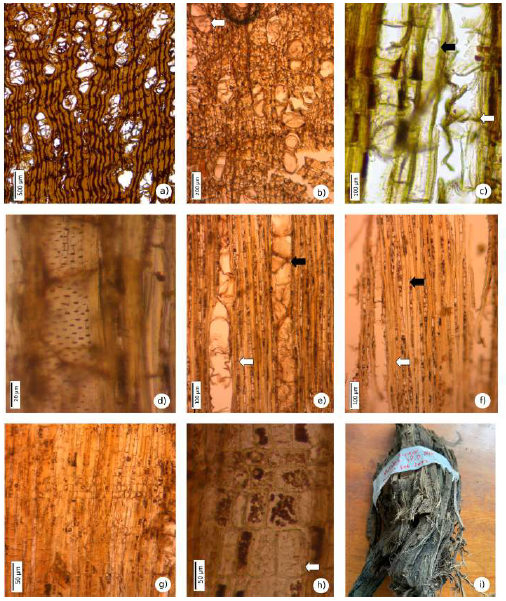

Description - Growth rings indistinct. Diffuse porous wood (Figure 5 a-c). Solitary vessels (36%), radial multiples two to three (up to 6) (Figure 5 a-c). Vessel elements round to oval in outline (Figure 5 b-c). Mean tangential vessel diameter 102 (70-200) um; 8 (6-12) vessels per square millimeter; vessel walls in transverse sections of 12 (6-16) um thick; simple perforation plates; intervessel pitting alternate 7-10 um (Figure 5 d); vessel-ray parenchyma pitting with reduced borders, horizontally elongate, and similar to intervascular pits (Figure 5 h). Mean vessel element length 200-400 um. Bubble-like tyloses common (Figure 5 b-c).

Uniseriate rays averaging 12 (7-20) cells, 535 (407-1188) um high, 22 (19-23) um wide (Figure 5 e-f). Some biseriate rays averaging 12 (8-21) cells and 904 (710-1210) um high, 28 (27-29) um wide (Figure 5 e-f). Rays 10 (8-11) per millimeter. Heterogeneous with procumbent body cells and usually one marginal row (Figure 5 g).

Fibers septate (Figure 5) and non-septate, thin to thick walls, pitting not observed. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse, and axial parenchyma in narrow bands up to five cells wide (Figure 5 a-c).

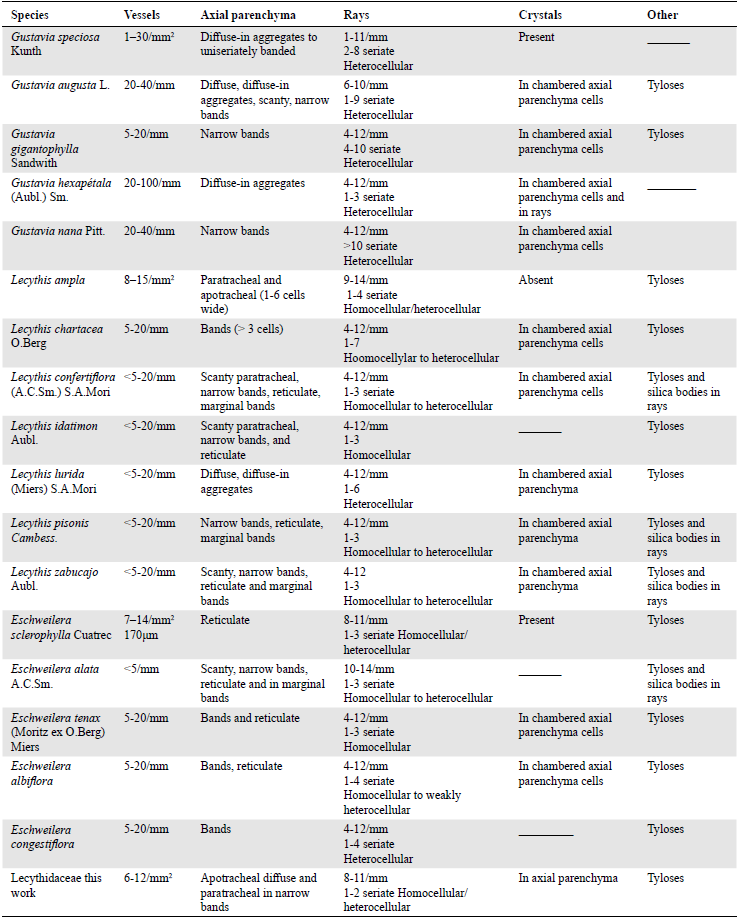

Remarks - The fossil wood studied exhibits a combination of features indicating an affinity with Lecythidaceae and Malvaceae. However, Malvaceae members generally have storied rays and scarce axial parenchyma (Wheeler et al., 1994). This fossil wood shows characters consistent with Lecythidaceae, such as parenchyma in apotracheal bands, simple perforation plates, alternate intervessel pitting, and two types of vessel-ray pitting. Additionally, rays are mostly 2-3 cells wide and distinctly heterogeneous to homogeneous, which aligns with the characteristics of Lecythidaceae (Diehl, 1935; Lens et al, 2007; Metcalfe & Chalk, 1950; Silva et al., 2022). Rays < 1 mm high lacking crystals and the presence of two types of vessel-ray pits generally distinguish the Lecythidoideae subfamily (Lens et al., 2007). The solitary vessels in small multiple tyloses, the parenchyma in continuous bands 1-2 cells wide, and the abundant less than 1 mm uniseriate rays with 1 or 2 marginal rows of square cells support its inclusion in Eschweilera and Lecythis (Metcalfe & Chalk, 1959) (Tabla 2).

Figure 5 Wood anatomical features of the mummified wood. a. Transverse section (TS). Diffuse porous wood. b. TS. Vessels in radial multiples and nearly absent parenchyma. c. Axial parenchyma apotracheal diffuse and axial parenchyma in narrow bands up to five cells wide. d. Longitudinal tangential section (LTS). Vessel elements, simple perforation plates, and alternate intervessel pitting. e. LTS. Tyloses and uniseriate rays and biseriate rays. f. LTS. Septate and non-septate fibers and uniseriate rays. g. LRS. Heterogeneous with procumbent body cells and usually one marginal row. h. Vessel-ray parenchyma pitting with reduced borders, horizontally elongated and similar to intervascular pits. i. mummified wood.

Comparisons with Lecythidaceae fossil woods

Approximately 12 fossil woods have been described (Gregory et al., 2009; Inside Wood Database, 2004-onwards) (Table 1). The following characteristics differentiate them from the fossil we describe here: Barringtonioxylon arcotenseAwasthi, 1969 from the Indian Neogene exhibits parenchyma aliform to confluent and wider rays (up to 8 cells) (Awasthi, 1969). Barringtonioxylon eopterocarpum from the Eocene of the Deccan Intertrappean Series, India, differs from our wood sample in that it has ring-porous wood and lacks radial canals (Prakash & Dayal, 1964). Barringtonioxylon mandlaense from the Deccan Intertrappean Series, India, has vasicentric parenchyma and fine to broad rays of two distinct types (Bande & Khatri, 1980). Careyoxylon pondicherriense reported in Paleogene sediments from southern India differs in having wider rays (up to 4 cells) and sheath cells (Awasthi, 1969). Careyoxylon chindwinnense from the middle Myanmar Miocene differs in having prismatic crystals in rays and thick-walled vessels (Gottwald, 1994; Inside Wood Database, 2004-onwards). Careyoxylon kuchilense described from the Tipam sandstones Formation Middle Miocene in India differs in the presence of scanty paratracheal parenchyma (Prakash & Tripathi, 1970). In the New World, Carinianoxylon brasiliensi from Brazil differs in having reticulate parenchyma (Kloster et al., 2017; Selmeier, 2003). Lecythioxylon brasiliensi and Lecythioxylon milanezzi described from the Neogene have lower vessel density and wider rays (Milanez, 1935; Mussa, 1959). Lecythioxylon enviraense, from the Acre Basin, Brazil, differs in having reticulate axial parenchyma more than three cells wide and the presence of crystals in ray cells (Kloster et al., 2017). Finally, from the Eocene of Perú, Cariniana valverdei has lower vessel density and scarce paratracheal parenchyma (Woodcock et al., 2017) (Table 1).

Scanning electron microscopy

Photographs were taken to examine the anatomy and preservation of the samples (Figure 3). The tangential section is shown in greater detail, revealing key anatomical features such as fibers, parenchyma, vessels, and intervessel pits (Figure 5).

Remarks - Mustoe (2018) identified three types of non-mineralized fossilized wood: mummified, charcoalified, and coalified. Mummified wood retains its original tissues with minimal chemical alteration, though they may exhibit distortion or desiccation. Charcoalified wood forms when wood is burned in an oxygen-deprived environment, reducing the organic material mainly to pure carbon. Coalified wood, in contrast, results from prolonged exposure to heat and pressure during deep burial, transforming the original organic material into a mixture of pure carbon and hydrocarbons.

Discussion

Subfossil wood has an economic importance in the wood industry, especially in Europe, where it is used in furniture (Beldean & Timar, 2021). In Colombia, information about subfossil wood is scarce - only two studies describe five subfossil woods identified as Terminalioxylon gumminae, Andesanthus risaraldense, Anacardium quindiuense, Chrysochlamys colombiana, and Goupioxylon stutzeri from the Pleistocene of the Central Cordillera (Ayala-Usma, 2014; Ayala-Usma et al., 2024).

The successful preparation, description, and dating of this sample confirms the high potential that non-mineralized fossil wood has for paleobotanical investigation. The processes described here can be replicated for future findings of this type of fossil. Our record confirms the presence of the Bertholletia clade (Lecythis/Eschweilera) in Valle del Cauca at least since the Late Holocene (Meghalayan).

This wood is an exemplar of mummified wood because it retains its original tissues with only minimal degradation of cellular components (Figures 1, 3, 5i) (Mustoe, 2018). The key conditions for mummification involve preventing microbial and chemical decay, typically in environments with deeply submerged wood, burial in impermeable sediments, arid regions, or cold climates. Also, this subfossil wood is frequently found in Quaternary deposits, where glacial, fluvial, and volcaniclastic lahar sediments create deep layers of fine material that aid in preserving organic remains (Mustoe, 2018).

Cali, where the fossil was found, is the capital of the department of Valle del Cauca and the third largest city in Colombia, with a population of approximately 2.28 million (DANE, 2018) and an average elevation of 1018 m. The surrounding area is highly urbanized, the Cauca River valley has been largely transformed, and only 1.4% of primary forest, mostly tropical dry forest, remains (Pizano et al, 2014).

The presence of the Lecythidaceae family in Colombia had been already reported. Berrio et al. (2002) described Couroupita santanderiensis fossil leaves from the Miocene of Santander and Huertas (1969) described a Lecythidopyon girardotanum fruit from Cundinamarca.

Lecythis and Eschweilera are non-monophyletic genera that share the greatest number of characters with our fossil and belong to the Lecythidoideae subfamily, which is dominant in the Amazonian forests and includes many emergent tree species (Vargas & Dick, 2020). Both genera vary from small to very large trees found throughout the Neotropics below 1500 m (GBIF, 2024) in México, Central America, Colombia, Venezuela, Amazonia, and Eastern and Central Brazil (Huang et al., 2015; Mori et al, 2017, 2007). The genera originated in the biogeographic regions of the Guiana, Amazonia, Cerrado-Caatinga, Mata Atlántica, and Transandean areas (Vargas & Dick, 2020). It is possible then that these species were typical of the dry forest-wetland transition that characterized this vast region before natural ecosystems were almost completely replaced by agricultural lands (Ramos-Pérez & Silverstone-Sopkin, 2018; Silverstone-Sopkin, 2012).

Late Holocene climate

The Valle del Cauca vegetation was dominated by tropical dry forests before the Industrial Revolution. The climate of the late Holocene, around 4,200 years BP, was a period characterized by increased aridity in mid- and low-latitudes (Meghalayan) (Berkelhammer et al., 2012; Walker et al, 2018, 2012). Many records show a rapid onset of aridification in the Mediterranean region, parts of Asia, North America, northeastern Brazil, and Africa (Bini et al., 2019; Booth et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2015; De Oliveira et al., 1999; Dixit et aL, 2014; Kaniewski et al., 2017; Thompson et al, 2002; Toth & Aronson, 2019; Utida et al., 2019, 2020). In Colombia, Berrío et al. (2002) described two sediment cores from the Valle del Cauca region with pollen, charcoal, and radiocarbon data. The Quilichao-1 core covers from 13,150 to 7,720 14C years BP and, after a gap, from 2,880 14C years BP to the present. The La Teta-2 core provides a continuous record from 8,700 14C years BP to the present. Maximum dryness was reached around 7,500 and 4,300 14C years BP, close to the 4,200 events. Additionally, pollen grains from Zone TET-1 (8850-7560 14C yr BP) show the dominance of dry forest taxa (Crotalaria, Croton, Tabebuia, Alchornea), while Lecythidaceae represents 8% of the pollen grains. Although the Valle del Cauca records for the late Holocene indicate an increase in aridity, the changes in precipitation were not large enough to modify its biome dominance; the valley was dominated by dry forests and wetlands/flooded forests during the Late Holocene and in modern times before the Industrial Revolution.

Conclusions

The discovery of a well-preserved subfossil tree in Valle del Cauca, Colombia, provides a rare and valuable insight into the ancient tropical dry forests of the region. The fossil wood exhibits anatomical features strongly indicative of the Lecythidaceae family, particularly aligning with the genera Lecythis and Eschweilera. These findings suggest that Lecythidaceae, a family now dominant in the Amazon forests, once flourished in the Valle del Cauca region, contributing to the region's biodiversity and ecological complexity. They further underscore that the region probably lost a considerable part of its biodiversity centuries ago, when natural forests were replaced by agricultural lands (Silverstone-Sopkin, 2012). The identification of Lecythidaceae in the fossil record highlights the long-term ecological stability and adaptability of this family. Furthermore, the preservation of this fossil wood suggests that specific environmental conditions, such as rapid burial and low oxygen levels, played a crucial role in the fossilization of wood. The climatic history of the Valle del Cauca region is a powerful reminder of the capacity of natural systems to adapt and evolve in the face of change, but also of their vulnerability. Learning from these records can help us anticipate future challenges and more effectively adapt our conservation and climate management strategies.