Introduction

This study takes a critical stance vis-à-vis hegemonic discourses of English, which associate this language, almost exclusively, with conventional understandings of socioeconomic development; that is, with what many language policies that prioritize English worldwide have referred to as better job and academic opportunities, quality of education, profitable business, and ease of intercultural communication and technological development (Coleman, 2010; Mohanty, 2017). Taking up debates about different ways in which the expansion of English has served as a mechanism of neo-colonization and cultural domination (Phillipson, 1992) and how this expansion has been resisted (Canagarajah, 1999) or locally reversed (Brutt-Griffler, 2002; Canagarajah, 2005; Kachru & Smith, 2008), this research explores the positioning of English, French, German, Portuguese, and Italian teachers at a university in Bogotá towards these hegemonic discourses. At the same time, it discusses whether these discourses resonate in languages other than English included in the institutional curriculum. A third dimension of interest is identifying other ways of making sense of language teaching and learning that are not necessarily aligned with instrumental and economistic development visions.

As noted (Cruz-Arcila et al., 2022), Colombia indeed represents a case in which anglonormativity, understood as the need to speak English to succeed personally and professionally (McKinney, 2016), has directly permeated national language policies. This has been mainly due to instrumental visions of languages that emphasize market interests (Mena & García, 2021). As Block (2018) rightly emphasizes, the market has become a dominant narrative that controls social institutions, such as education, by presupposing that it should mainly aim at developing individuals’ skills and competences that make them “more saleable” (p. 577).

Today, when the global market narrative is imposed on social institutions, language policies in Colombia have been based on instrumental discourses of competitiveness, globalization, internationalization, and economic prosperity (British Council, 2015; Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], 2005, 2014), which constitute a single perspective of socioeconomic development. In Colombia, these initiatives often seem to favor more the interests of international agencies than local needs (Bonilla-Carvajal & Tejada-Sánchez, 2016; Hurie, 2018; Mackenzie, 2022), which could have negative consequences by, for example, intensifying exclusion and social gaps. Therefore, considering that such discourses and linguistic policies have had a substantial impact on the configuration of the national curriculum and teacher training programs (Castañeda-Trujillo, 2018; González-Moncada, 2009), it becomes relevant to investigate how these mercantilist and dominant narratives about the value of teaching modern languages are related to the meanings that university teachers themselves give to the languages they teach. Thus, this study sets a dialogue between the dominant discourses of English and the social representations of English and other languages while exploring possible alternative meanings of socioeconomic development.

We took teachers’ perspectives because of the importance of their point of view in promoting the languages they teach and the multiple drives they may have for doing so. Hence, it is crucial to analyze how aspects such as teacher training or the promotion of each language have taken place in Colombia, either through university programs and/or the internationalization and cultural expansion policies of some European countries. An examination of these issues allows us to claim that, in Colombia, the training of language teachers has maintained a Eurocentric dependence relationship that, at the same time, highlights and legitimizes traditional visions of development (Castañeda-Trujillo, 2018; Le Gal, 2018). For instance, from a critical reflection on the curricula of English teacher training programs, Castañeda-Trujillo (2018) argues that there is a strong tendency to replicate colonial power dynamics, evident in the promotion and legitimization of teaching methods validated by the West and its visions of what can be considered good teacher education. This dynamic would prioritize the neoliberal interests of multinationals dedicated to the promotion of foreign languages, which benefit from the commercialization of training programs, certifications, international exams, and short courses, among others (Bonilla-Carvajal & Tejada-Sánchez, 2016; Le Gal, 2018). Likewise, teachers’ training and professional role are reduced to a technicist and functional dimension (Guerrero, 2010), favoring capitalist ideals.

Due to the centrality given to English in national language policies, research on promoting languages such as French, German, Italian, and Portuguese, and their relation with socioeconomic development (Rincón Restrepo, 2020; Silva, 2011), has been less relevant. It seems that the promotion of other languages is in tune with these same global capitalist principles, which, although not as evident as in the case of English, are part of the internationalization policies of some European countries that see their linguistic/cultural capital as an opportunity for economic expansion (e.g., German Foreign Office, 2020; MAECI, 2014). However, in Colombia, how language teachers position themselves toward the prioritization of English is yet to be studied. Moreover, concerning this linguistic hierarchy, other languages could also represent opportunities for socioeconomic development, or better yet, how other possible alternative understandings to the hegemonic developmentalist vision could be established. These gaps precisely highlight the relevance of this study, mainly because we inquire into these possible alternative discourses to the mercantilist notion of development, determined by capital accumulation, wealth exchange, and industrialization (Bresser-Pereira, 2019). Examining these other possible meanings of the relation between socioeconomic development and learning/teaching modern languages reaffirms our critical stance. It invites us to question the discursive and ideological constructions that operate as a mechanism of Western cultural, social, and economic hegemony (Ziai, 2007).

A Postdevelopmentalist Perspective on Language Teaching and Learning

In Latin America, the concept of development as a Western benchmark of social organization has been, since the mid-20th century, at the center of the public policy debate. Since then, different approaches to understanding it have emerged, which can be grouped into two: hard and soft theories (Sen, 1998, as cited in Vergara Erices & Rozas Poblete, 2014). Hard theories emphasize money, capital accumulation, and industrial production, while soft theories focus more on quality of life, people, and the environment. Taking the world economic powers as the primary yardstick, hard theories have been hegemonic globally, understanding industrialization, technological innovation, urbanization, and market centrality as unequivocal development factors (Sen, 2015). This instrumental stance continues to permeate public policies at the global and local levels (Cuestas-Caza, 2019), resulting in a widening of social gaps by ignoring situated socioeconomic realities.

The hegemonic approach to development has imposed the market and competitiveness as the driving forces of everyday social practices, becoming a dominant narrative that also permeates L2 education. From the conventional developmentalist angle, the competitiveness and labor value language learners may achieve have become the leading indicators of success (Block, 2018). Thus, the promotion of language policies in countries such as Colombia has unreservedly adopted this notion which, in turn, privileges the teaching and learning of English as an apparent guarantee of socioeconomic growth. Following this reasoning, languages—especially English—are reduced to marketable products (Soto & Pérez-Milans, 2018). Likewise, L2 education is reduced to responding inertly to the underlying economic and mercantilist narratives imbued in national language policies.

In Colombia, a country marked by inequality (World Bank Group, 2021), it could be said that public policy aligned with traditional visions of development is not beneficial, as it does not contribute to equal access to opportunities and, on the contrary, seems to favor the elites (Mackenzie, 2022; Mohanty, 2017). As an example, in the results of Pruebas Saber 11 in 2021—an exam high school students must take to enter higher education institutions—the schools with the best scores, particularly in the English component, were bilingual institutions with tuition costs that only the national elite can afford (MEN, 2022). It could be argued that the specificity of the local context and the educational system respond to the global economistic dynamics. This highlights that language education is guided mainly by anglonormativity, where English is seen as the language of development and the only linguistic response to geopolitical and cultural problems (Coleman, 2011).

Consequently, underlining the tensions between L2 learning/teaching and development in Latin America allows us to ask ourselves, from a postdevelopmentalist theoretical framework, about possible alternatives to those dominant discourses that privilege English. By understanding development as an ideological discursive construction of Western origin that operates as a mechanism for cultural, social, and economic hegemony (Ziai, 2007), postdevelopment represents a constructive alternative to neoliberal discourses (Sachs, 2019). Following Escobar (2005), we understand postdevelopment as a theoretical space in which social and economic life ceases to be organized from the economistic premise. Therefore, the concept of economic growth based on the exploitation of nature, the commodification of human relations, and individualism is questioned. This theoretical vision interrogates the underdevelopment/development dichotomy underlying the hegemonic visions on the subject (Escobar, 1996/2014) and rescues alternative conceptions of progress and welfare in which the political participation of individuals concerning their contexts and particular needs prevails.

An excellent example of alternative understandings is the Plan Nacional de Desarrollo para el Buen Vivir or Sumak Kawsay (Calderón Paredes, 2014), promoted in Ecuador, which aims at social equality, the integration of peoples and territories, respect for diversity as well as the recognition of indigenous cosmovisions. Following Walsh (2010), the promotion of ancestral languages in education could facilitate familiarity with the knowledge, wisdom, and history of our peoples, which would be part of an authentic critical interculturality (i.e., a view of difference from below, through a constant interrogation of hierarchies and interiorization). Such initiatives contribute to decolonizing ourselves from Western knowledge and questioning the epistemic violence in the developmentalist homogenization and instrumentalization of languages.

Another alternative to predominant instrumental narratives of L2 education is attached to well-being. Here, we could mention the daily uses of languages in activities that generate enjoyment, such as social networks (Campos Bandrés, 2021). Likewise, it is possible to identify alternatives that highlight incentives derived from less instrumental desires and interests (Cruz-Arcila et al., 2022), where emotional realizations and the satisfaction of concrete social needs take more relevance. These two examples highlight the importance of this study’s postdevelopmentalist angle, as it emphasizes the role of localized contexts and social practices related to the enjoyment and satisfaction of individual needs and interests over tangible economic benefit.

Anyhow, postdevelopment is not a mere superficial recovery of the ancestral, nor the construction of a hybrid model in which the tensions and critical visions are overridden (Escobar, 2019). The focus is a transition towards plurality. That is, postdevelopment theory interrogates the narrow economistic goal of development and proposes considering the needs of individuals, their contexts, and the construction of socially equitable relations. Particularly, in L2 education, it is worth asking ourselves about the multiple meanings that can be constructed around language teaching/learning and the connections with multifarious ways of understanding socioeconomic development.

Method

Following the social representations theory, this study is informed by what is known as the plurality of approaches (Petracci & Kornblit, 2007). It is a principle concerned with understanding how social subjects attribute symbolic value to objects that are significant to them. Relatedly, the structural view of social representations was used. Such a perspective conceives social representations as structures of knowledge of topics of social life, shared by groups and formed by cognitive elements linked together. The central core theory underlies this approach. It argues that social representations are a double system formed by two components: a central core and a peripheral system. The core is a restricted concept set that defines and organizes social representations. The peripheral system comprises most elements with a conditional nature and is more flexible and practical, adapting the representation to everyday experiences (Wachelke & Wolter, 2011).

Thirty-six professors from the Modern Languages undergraduate program of a university in Bogota participated. Such a program emphasizes language learning about entrepreneurship and sustainability, which added relevance to the sort of analyses of socioeconomic development aimed at by the study. The program requires students to learn English as a mandatory language, plus two additional languages chosen out of French, German, Italian, or Portuguese. Most teachers teach only one of these languages. A general characterization of the participants is listed in Table 1.

Two data collection techniques were used: questionnaires (n = 34) and focus interviews (n = 18). Teachers took part in the study voluntarily. The questionnaire comprised 27 questions to gather ideas of ways teachers may link the languages taught with socioeconomic development. Following the structural approach of social representations, one section of the questionnaire was the free association of concepts: Informants were asked to provide five concepts or short expressions that first came to their minds concerning each language offered in the program. Moreover, teachers were asked to associate categories of traditional (e.g., economic growth) and alternative (e.g., personal achievement) ways of understanding development with the languages taught in the undergraduate program, followed by a brief explanation of their choices.

Five focus interviews were conducted with an average duration of 1.5 hours. An attempt was made to have a teacher of each language in each interview. The focus was to discuss the results of the questionnaires.

We obtained both discursive and closed-ended information. The discursive data were first analyzed manually following a thematic approach and later triangulated with Atlas.ti. The evocations obtained in the free associations of words were analyzed through the OpenEvoc program (Scano et al., 2002), which allows a structural approach to delineate social representations. Such a tool helped examine the different meanings teachers construe about the languages of interest. A hypothesis of centrality, zones of contrasts, and peripheral zones of evocations were identified for the whole set of responses and the groups of teachers of the specific languages. The tables generated by the OpenEvoc program are read as follows: The first quadrant, at the top left (++), gathers the terms with the highest frequency and placed by the respondents in the first places, thus constituting the hypothesis of the central nucleus (Wachelke & Wolter, 2011). The second quadrant, in the upper right part (+-), is the first periphery, with the evocations of higher frequency but with a different average location, that is, mentioned in the last places, which connoted less importance for the subjects. The third quadrant (-+), on the lower left, contains the terms of lower frequency and the high average order of evocation; that is, terms not very often mentioned but evoked in the first places by the subjects. Finally, the fourth quadrant (--), on the lower right, are the terms of both lower frequency and last positions of evocation (see Table 2 in the Postdevelopment Cracks section).

Findings

Accepting Hegemony: An Instrumental View of the Relation Between Language and Development

From the analysis of teachers’ social representations of the relationship between language learning and socioeconomic development, the central tendency was an uncritical acceptance of the hegemonic developmentalist views. This section discusses this finding, highlighting the absence of a critical perspective on language teaching/learning.

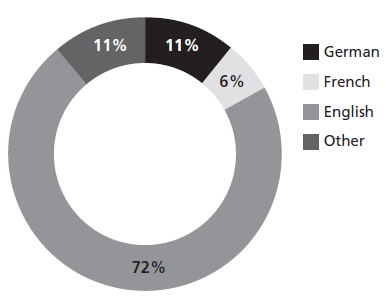

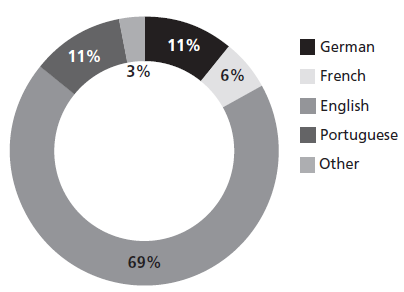

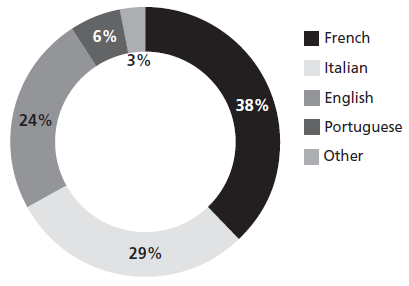

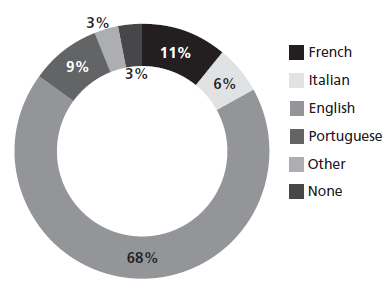

The data show that, in the view of teachers, second languages, especially English, guarantee economic growth (Figure 1) and job opportunities (Figures 2 and 3), which to a certain extent facilitate access to culture—understood as a consumer good. Following Bourdieu (1979/2002), consumer goods are an important part of the habitus that socially and symbolically distinguishes and differentiates social groups. Thus, language learning would play a role in these acts of distinction by perceiving languages as tools to access and dominate consumption goods (e.g., money, job, culture).

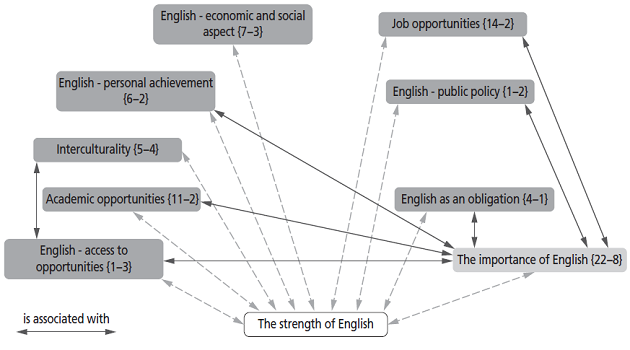

This commoditized view of language learning was confirmed in the semantic relationships emerging from the analysis in Atlas.ti. As observed in Figure 3, the strength of English is constructed around the same instrumental evocations (e.g., job and academic opportunities, access to culture, and economic and social capitals).

Following on from this observation, the notion of development and its relation to language learning would be based, as Patricia1 states, on the unique possibility offered by the mastery of an L2 to have contact with other countries and cultures, which would allow, collectively, the construction of a more “developed” society:

Language teaching allows students…to achieve other economic and professional positions…many opportunities…arise when you can communicate in another language, work for another country, for companies, you are not limited only to your country…when you have this working tool…it allows you to develop as a person.2 (Focus interview)

Along the same lines, Martha is confident that teaching and learning an L2 guarantee development. Hegemonic principles permeate this discourse by relating education as a possible guarantee of social mobility and, therefore, of socioeconomic development: “Surely [learning languages] will generate socioeconomic development oriented from pedagogy, from teaching, from education…other facets in which socioeconomic development will be generated” (Focus interview).

Drawing on Bourdieu (1979/2002), the above could be interpreted as a symbolic dimension of cultural recognition, as an exercise of distinction of social groups in terms of access to consumer goods. Therefore, such distinction/recognition that comes with learning prestigious languages underscores an instrumentalist vision of language learning and teaching that reduces them merely to instruments for accessing better job opportunities. In this regard, Álvaro notes: “We could also be talking about employment opportunities…so speaking more than one language, even if it’s not like a native, is very important…because it can open several doors” (Focus interview).

Alvaro’s words stress the implicit association between employment and proficiency in a foreign language and underline an apparent alignment with the commoditization of L2. Beyond that, Alvaro also accepts and exalts the privileged vision of the native speaker by pointing out a scale of subordination to their imagined linguistic supremacy.

Likewise, it was interesting to find that when speaking of personal achievement and social prestige and their relationship with language learning, it is impossible to read any questioning of the dominant instrumental anglonormative narratives. However, there is a salient ambivalent position when assuming a priori that learning English should not be understood as a personal achievement since it is an obligation in all academic training. As some participants stated:

I will learn English because it is practically a necessity, and one becomes a little illiterate. (Luisa, Focus interview)

English…responds to an academic or even professional issue; it already becomes…a global communication need, so more than a personal achievement, I see it more as a necessity. (Natalia, Focus interview)

Let’s say that it is no longer a plus but an obligation for a professional in the labor market today to have proficiency in the English language. (Sandro, Focus interview)

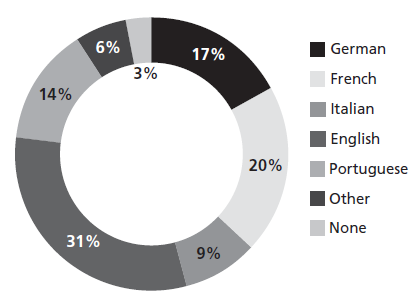

Interestingly, in contrast to what Natalia says, when it comes to personal achievement, English was also the most highly regarded language (Figure 4). Nonetheless, in tune with what we have called “the comfort of the hegemonic,” this perception seemed derived from anglonormative development views. As Sabrina puts it:

[Learning English] is a personal achievement, and I know that in our Colombian families…the fact of speaking English is a success; it is a personal achievement. So, that’s how I consider it and the work and academic travel experiences I have had thanks to this language. (Focus interview)

Sabrina, thus, associates personal achievement with tangible personal gains mainly. However, for others, such association is constructed with the difficulty of learning languages such as German. These beliefs are problematic as they appear to be detached from any consideration of social reality, where, for example, severe issues of inequality in Colombia (World Bank Group, 2021) are viewed as important factors. Relating personal achievement to linguistic distance from Spanish (the case of German) means not considering social factors that affect the learning/teaching processes.

Relatedly, the excerpts below suggest that the value of personal achievement is configured in terms of an imagined notion of challenges derived from the apparent difficulty of some languages and instrumental benefits, such as access to scholarships.

I would have thought that German would be a little higher than English [in terms of personal achievement] because students always say: “Oh no, I am interested in German because it is a challenge”…they think…that it is tough and then it turns out that it is not. (Trina, Focus interview)

After English, I would say German because of all the [academic] possibilities that Germany offers…It is the country that offers the most scholarships. (Camilo, Focus interview)

From a colonial viewpoint, learning a dominant language is a guarantor of prestige, economic growth, and job opportunities, which also underlies the belief that being multilingual is mainly limited to mastering dominant-western languages. Intriguingly, according to Ignacio, these languages would ensure job opportunities in Latin American contexts but not in Europe where it is “normal,” almost natural, to be multilingual, and such linguistic competence offers neither prestige nor economic growth:

In other countries, it is normal for any ordinary person…to speak two or three languages; and, in reality, this does not open doors or does not benefit them because, in the end, they are like one more in the crowd who, by the same educational system, already have access to speak two or three languages, to be…a polyglot. But that is not common in our country, so when you have access to that, you obviously have an advantage. (Focus interview)

In broad terms, concerning the general perception of each of the languages of focus in this study, we can argue that social representations seem to follow hierarchical dynamics. This is evident in three general observations: (a) English continues to be perceived and accepted as the dominant language; (b) French and German are often associated with academic opportunities and social prestige and would be second on the scale of relevance; and (c) from the instrumentalist viewpoint of development, Portuguese and Italian tend not to be perceived as very closely related to labor or academic opportunities.

As seen in Camilo’s words, in the hierarchy of social representations we have identified, languages other than English are not significantly associated with economic value; they are seen mainly as cultural capital: “French [is] the language of culture, like Italian, so I would study French and Italian to be cultured” (Focus interview).

Camilo’s configurations of Italian and French seem to derive from the stereotypes that the very dynamics of internationalization of these languages perpetuate, presenting these merely as cultural archetypes. These words resonate with the instrumentalist and colonial vision of language learning and teaching, a Eurocentric vision that values as cultured only that related to the knowledge of the old continent. An interesting example of this view is the relationship participants establish between L2 and artistic production (Figure 5). As noted, dominant European languages are the most associated with artistic production, and only a low percentage of teachers (3 %) signaled that there might be other languages worth considering.

In closing, by analyzing the relationship teachers establish between development, culture, and interculturality, we found that, on the one hand, it is not possible to identify a critical stance towards what is understood by development nor by culture; and, on the other hand, that such relation tends to be monolithic, superficial, and functional to the system (Walsh, 2010). This is evident in the following excerpts, where interculturality is referred to as a capacity limited to an exchange of information and to establishing communication bridges—all this to be replicated in the classroom.

Interculturality is the capacity I have to understand and communicate to interact with other languages, and that is what is taught in this undergraduate program. (Camilo, Focus interview)

I understand intercultural communication as an exchange of information that goes beyond simply sharing a language but also having access to specific information related to the culture. (Ignacio, Focus interview)

The intercultural speaker is the one who can see their culture [and] the target culture and establishes…a bridge between the two. (Sabrina, Focus interview)

Returning to Walsh’s (2010) critical position, this view of the relation among cultures is the result of colonial patterns in which the inter-relation is not understood as a space of dispute and negotiation that makes visible the tensions framed in the differences “that maintain inequality, inferiorization, racialization, and discrimination” (p. 79, own translation). This notion of interculturality is functional to the neoliberal system. This research also confirmed a conceptualization since English is seen as the language most closely related to intercultural communication (Figure 6).

The apparent absence of a critical stance on the part of the teachers allows us to evidence a comfort with hegemonic discourses and, therefore, a naturalization of the instrumental view that guides the relationship between language learning and development. What role would L2 learning/teaching play in constructing critical interculturality in Colombia? The challenge would be to question this instrumentalist understanding, be aware of the acritical accommodation to hegemony, and orient language teaching/learning towards more critical reflections and positionings. There is hope, but we will deal with that in the following section.

Postdevelopment Cracks

Despite the above more salient bias towards traditional relations between socioeconomic development and language learning, from a postdevelopment lens, the data also allows us to identify some tensions that suggest that the instrumental benefits of learning English or any other L2 do not entirely exhaust the complexity of meanings teachers themselves have constructed around being language learners and teachers. Drawing on the theoretical-critical stance underpinning this study, we associate these tensions with what Walsh (2017) calls “fissures and cracks, where otherwise thinking, small hopes dwell, sprout and grow” (p. 31, own translation). That is, we read such tensions as emerging options to transgress dominant narratives and, therefore, begin to open the field to alternative interpretations. Of note is that such tensions also illustrate the dilemmas and contradictions teachers experience in their everyday practice. They negotiate between instrumental and neoliberal drives with less evident but relevant alternatives to make sense of language learning. As shown in this section, the importance of the local, situational, and individual and the concern for social inequality are essential starting points to open fissures towards such alternative understanding.

Sandro and Carolina, for example, emphasize that there should be a more situational and individual approach, where meeting the English “requirement” is not necessarily associated with socioeconomic development. The relationship between socioeconomic development and language learning cannot be reduced to only learning the languages of the economic powers under the taken-for-granted premise of more and better opportunities. Furthermore, it is also necessary to consider the agency and particular interests of individuals who have countless ways to configure and project themselves into the “pluriverse” of socioeconomic development (Escobar, 2019). The purely economistic discourse could be conceived as one of these options, but not the only one. As some participants emphasize,

Economic development does not depend on the power that speaks the language but on its conscious and responsible citizens who defend the public sector and its institutions. (Danna, Questionnaire)

[Development involves] the formation of a country’s values, of a whole cultural, sociocultural system, which is stronger than the economic and political…the economic is one aspect, I would say…the cultural is much stronger, for me culture is everything: the way of thinking, of acting, of discussing something…that is very strong. (Camilo, Focus interview)

Although Camilo fully aligns with a hegemonic discourse of development, he highlights a dimension of development that is conventionally less emphasized but equally valid. The development also has to do with the negotiation and configuration of sociocultural identities. This type of representation interrogates the monolithic instrumental and capitalist development narrative and paves the way for considering that, following Walsh (2010), critical interculturality emerges as an alternative. Camilo points out “training in values” and “the way of thinking, acting, and discussing something” as elements that cannot be ignored when relating language learning to socioeconomic development. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to think that the negotiation of values and ways of acting may be motivated by decolonial agendas, which question and seek to transform unequal social relations and structures that allow us to recognize and project ourselves toward multiple visions of being, knowing, and learning.

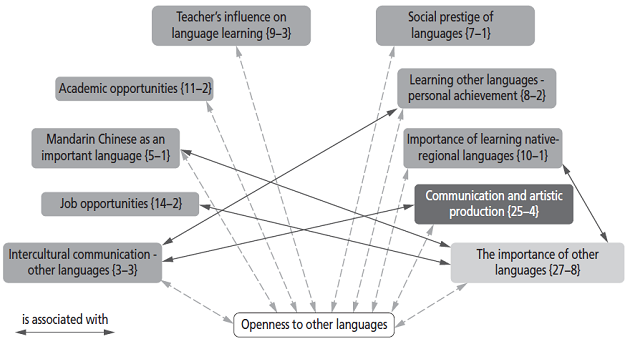

An important observation emerging from the hypothesis of a central nucleus of social representations around languages stresses this possible fissure where more critical configurations can manifest themselves. As seen in Table 2 and Figure 7, there are contradictions and uncertainties in how L2 may relate to socioeconomic development. Despite the apparent overarching uncritical acceptance of hegemonic discourses of development discussed previously, concepts such as “culture” and “interculturality” were frequently evoked (OpenEvoc) and discursively present (Atlas.ti) in teachers’ social representations. By itself, this observation already represents an alternative counternarrative to the more instrumental dominant discourses of L2, to views of languages as currencies of exchange or interchangeable resources in the market (Mena & García, 2021).

Table 2 Structural Elements of Social Representations on English, German, Italian, Portuguese, and French

| ++ | Frequency >= 2 / Order of evocation < 3 | +- | Frequency >= 2 / Order of evocation >= 3 | ||

| 7% | Culture | 2.57 | 2% | Globalization | 3 |

| 2% | Interculturality | 2.75 | 2% | Opportunity | 3.75 |

| -+ | Frequency < 2 / Order of evocation < 3 | -- | Frequency < 2 / Order of evocation >= 3 | ||

| 1.5% | Literature | 2.33 | 1.5% | Study | 3 |

| 1.5% | Communication | 2.67 | 1.5% | Creativity | 3 |

| 1% | Meaningful | 1 | 1.5% | Pronunciation | 3.67 |

| 1% | Meaningful learning | 1.5 | 1% | Communicative competence | 3.5 |

| 1% | Learning | 2 | 1% | Passion | 3.5 |

| 1% | Opportunities | 2 | 1% | Films | 3.52 |

| 1% | Didactics | 2 | 1% | Tourism | 4 |

| 1% | Interaction | 2.5 | 1% | Sociability | 4.5 |

| 1% | Share | 2.5 | 1% | Knowledge | 4.5 |

Although it is not possible to identify a critical stance on the notions of “culture” and “interculturality” (+-), the fact that they have a more privileged place in social representations compared to more instrumental constructs such as “globalization” and “opportunity” is, to use Walsh’s words again, “a small hope” that there is a crack, a fertile ground for cultivating alternatives to the dominant instrumental discourse. The analysis via Atlas.ti also supports this small hope. As seen in Figure 7, concerning the interest in intercultural communication and interculturality, a promising openness towards other languages (primarily regional ones) and the relevance given to personal achievements are deviations of purely instrumental configurations.

Similarly, as Bibiana points out, social equality would become an important reference to interrogate the monolithic discourse of development. It is not a question of whether there are more opportunities but how they are thought of and who can access them. This is an important observation because it calls into question the prioritization given to English globally, which, at the same time, is at odds with the rhetoric of justice and equity promoted in language policies, such as the bilingualism initiatives in Colombia (for critiques in this regard see Cruz-Arcila, 2017; Hurie, 2018).

Thus, Bibiana understands development as “all those activities that allow a country to develop economically but also from a social point of view, that is, to guarantee…equity…gender equity, race equity, everything” (Focus interview).

Considering socioeconomic development concerning social equity objectives brings to the debate Sen’s (2009) and Nussbaum’s (2011) proposals of capital accumulation as relevant only insofar as it guarantees human development. As defined by these authors, the opportunity to lead the type of life deemed convenient guarantees decent standards of life quality. Although instrumental ideals still frame this vision, it represents an interesting way to question the excessive importance given to the mere accumulation of capital for its own sake and to ask for other forms of constructing the notion of development in light of alternative vocabularies. For example, having social equality as an aim could be an important platform for breaking down the stratification that tends to be established between languages themselves, according to their allegedly universal instrumental value. As some participants state,

I do not consider that there is a general criterion applicable to the importance of each language. This depends on what you want in terms of work and the opportunities you want to achieve in the different fields of interest. (Kelly, Questionnaire)

There is a lack of awareness of the reality…when other languages do not appear, it shows that we still need to work on the awareness of the importance of these other languages. The importance is indisputable. If it does not appear in the research, people did not answer because they are not aware of that importance. (Patricia, Focus interview)

Both excerpts emphasize that all languages are necessary if one takes a more localized view of their role. Patricia’s comment, in particular, shows that the subsidiary value that tends to be given to languages other than English is often caused by ignorance. In other words, the dominant discourses that privilege English have overshadowed other instrumental and intrinsic meanings more associated with other languages. The concern for social inequality makes it easier to realize how the hierarchies between languages are not helpful.

Finally, another point representing alternative postdevelopment cracks is constituted by what Sabrina called “personal satisfaction.” “Pleasure,” “passion,” “creativity,” “interaction,” and “sociability” were concepts that, despite not being quite recurrent in the analysis of teachers’ social representations toward languages, create a semantic framework that helps to counteract the instrumental hermeticity with which language training tends to be understood. Echoing Campos Bandrés (2021), it could be argued that the emotional dimension underscored here, the enjoyment and satisfaction of self-interests, could well be understood as another form of development we should consider more.

Conclusions

Questioning dominant and anglonormative narratives about the relation between language learning and possibilities for socioeconomic development from the teachers’ perspective in Colombia has allowed us to identify several tensions and possibilities for more critical configurations. First, perhaps in response to the Eurocentric dynamics in which teacher education programs are developed in the country (Castañeda-Trujillo, 2018; Le Gal, 2018), the centrality of the market and the satisfaction of real instrumental needs stand out as drives for L2 learning; hence, the uncritical acceptance of the supremacy of English reported here. This absence of a critical perspective is evidenced primarily in the instrumentalist vision of languages as tools for accessing job opportunities and cultural exchanges, always privileging Western values, which underline a naturalized colonial worldview. Teachers’ representations seem to be aligned with the neoliberal educational system, which parametrizes competences, achievements, and skills, a system where education itself is framed within the values of the market. This dominant understanding is problematic, as it leaves aside the local context’s particular needs, problems, and possibilities, characterized, as pointed out above, by huge social gaps.

On the other hand, following Walsh (2017) and Escobar (2019), the lens of postdevelopment has made it possible to detect “cracks” to cultivate alternative meanings, which are less instrumental and more sensitive to local social realities. One of them is the possibility of constructing cultural identities from a more critical and less functional positioning towards the status quo, in which language teaching can also serve to question structural inequalities among diverse sociocultural groups. Relatedly, a concern for social equality was identified as a constituent factor of socioeconomic development. This concern represents a counternarrative to purely economistic, instrumental, and anglonormative visions by implying the need to question and overturn different types of social hierarchies, including those that tend to be established between languages themselves as more/less valuable. A third possibility, from the postdevelopment angle, is the emotional dimension, which draws attention to the relation between learning languages and the satisfaction of particular interests, achievements, and passions, which can be viewed as relevant spheres of individual and, thus, collective development.

Identifying both alignments and critiques of neoliberal views of L2 illustrates the complexity and contradictions of the social representations teachers have construed around their practice. Interestingly, the alignment with the predominant hegemonic positionings paradoxically represents the main path of action to build more plural development options to deconstruct the current neoliberal-colonial discourse, which permeates the teaching work per se. For instance, for the modern language program analyzed, the views discussed above underline neglect for the local since the interests, needs, and resources specific to our context and individual motivation, beyond the economistic level, tend to be eluded or denied. Therefore, an initial step towards a more pluralistic and reflective approach to development would be the recognition of this uncritical positioning, which would open the space for a less monolithic and hermetic approach to development. The possible opening to multiple possibilities of thinking about development, considering the social and political particularities, and consequently the local linguistic and cultural diversities, is an invitation to understand that instrumentalist motivations represent only one possible dimension of socioeconomic development and that investigating and recognizing other alternatives is a critical endeavor we could all contribute to from our L2 classrooms.