Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders can arise from improper postures and prolonged adaptation to them. These postures are prevalent in the workplace, particularly in critical health areas where nursing professionals are stationed. Poor posture can hinder physical performance and adversely impact the professionals' health 1. This is due to the physical exhaustion caused to the anatomical structures from a lack of recovery time, along with the emergence of other symptoms that affect the individual 2.

The body parts most affected by this disease include muscles, tendons, bones, ligaments, cartilage, and nerves, leading to conditions ranging from mild, temporary discomfort to severe, permanent damage that can result in an inability to work and a decreased quality of life 3.

Most musculoskeletal diseases are cumulative, resulting from repeated and prolonged exposure to biomechanical and systemic risk factors. These diseases primarily affect the back, neck, shoulders, and both upper and lower extremities 4,5.

These types of situations have significantly increased in recent years, impacting nursing professionals regardless of their age and gender 6. They can result in disability, personal or familial instability, or loss of income due to absence from work thus destabilizing the financial situation of any family 7.

The World Health Organization (WHO) mentions that unusual working conditions are a significant source of biomechanical risks. These conditions can include manual handling of patients, loading and unloading stretchers, performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, forced postures, and physically demanding tasks. Such tasks can pose a risk of muscle damage, especially during transportation and executing urgent patient procedures. These are routine tasks that heighten the probability of musculoskeletal injuries 8. Additionally, the broad variety of physical demands can be challenging to assess as patient requirements and calls vary widely. Lower back injuries are the most prevalent condition among hospital professionals and are becoming increasingly common 9.

In the European Union, 23% of health workers report muscle discomfort and disabilities due to neck pain, as well as pain in the upper and lower extremities. Meanwhile, the prevalence in Latin America ranges between 9% and 12% 10. According to the General Insurance of Occupational Risks in Ecuador, from 2013 to 2015, there were 674 recorded occupational diseases, with a staggering 93.92% corresponding to pathologies related to musculoskeletal disorders. The primary disorders include herniated discs, low back pain, and carpal tunnel syndrome 11. In their research, Naranjo et al. report that among nursing professionals the most prevalent musculoskeletal disorders are lower back pain (62.4%), neck pain (56.3%), and knee pain (51.2%). These all contribute to increased rates of absenteeism from work 12.

Nurses working rotating shifts are more likely to develop musculoskeletal disorders. These disorders include back pain from overwork, dermatitis, gastritis, osteoarthritis, migraines, conjunctivitis, urinary tract infections, tendonitis, and shoulder pain. They are also prone to mental health conditions such as stress, burnout, anxiety, and depression, among others 13,14.

Physical, psychological, personal, and professional factors are associated with these disorders. The strongest evidence relates to physical demands, particularly load handling, poor posture, and repetition. Like psychosocial demands, these can directly affect physical stress as time pressure increases movement acceleration and exacerbates poor posture. Furthermore, these factors can influence pain sensitivity, interfering with proactive care and symptom reporting. Personal characteristics such as age and gender are relevant, and occupational characteristics include intense job demands 15.

Certain health problems can lead to a loss of attention, thereby increasing the risk of errors at work. This includes a diminished ability to recognize life-threatening signs and other factors impacting patient safety. Nurses work in complex situations and often need to make critical decisions that affect people's lives. The nursing staff's ability to respond aptly and promptly to everyday healthcare needs is undoubtedly linked to their own health status 18.

This research holds significant social impact, as it reveals the factors associated with musculoskeletal disorders prevalent amongst the nursing staff. These disorders can initiate changes in body structures including muscles, joints, tendons, etc., primarily instigated by workplace conditions. Given the reasons above, this systematic review aims to scrutinize the scientific literature on factors linked to musculoskeletal issues affecting nursing staff in critical areas of health institutions. Therefore, this will pave the way for the future implementation of protocols for the prevention and treatment of issues encountered by staff in their daily routines.

Materials and Method

This study used a narrative approach and extracted information from the following databases: PubMed, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and the Scielo Electronic Library, in Portuguese, English, and Spanish. We developed search equations using the following terms: musculoskeletal diseases, nursing staff, working conditions, low back pain, intensive care unit, and emergency. These terms were combined using the Boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT.

During October and November 2023, a bibliographic search was conducted, with a focus on primary research, using the protocol outlined in the PRISMA declaration as a reference. The review was subsequently registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD 42023485858). The extraction, selection, and analysis of the information were then conducted in December 2023 and January 2024.

Articles published in the recent eight years (2015-2023) were chosen for analyzing the most current literature. The selected articles were descriptive and correlational cross-sectional studies, written in Portuguese, English, and Spanish. These articles highlighted the musculoskeletal conditions of nursing professionals and possible associated factors. Only open-access articles were considered. Grey literature, books, opinion pieces, reports from organizations, articles lacking scientific arguments, clinical guides, systematic reviews, studies authored by professionals outside of nursing, and those with subpar research quality were excluded.

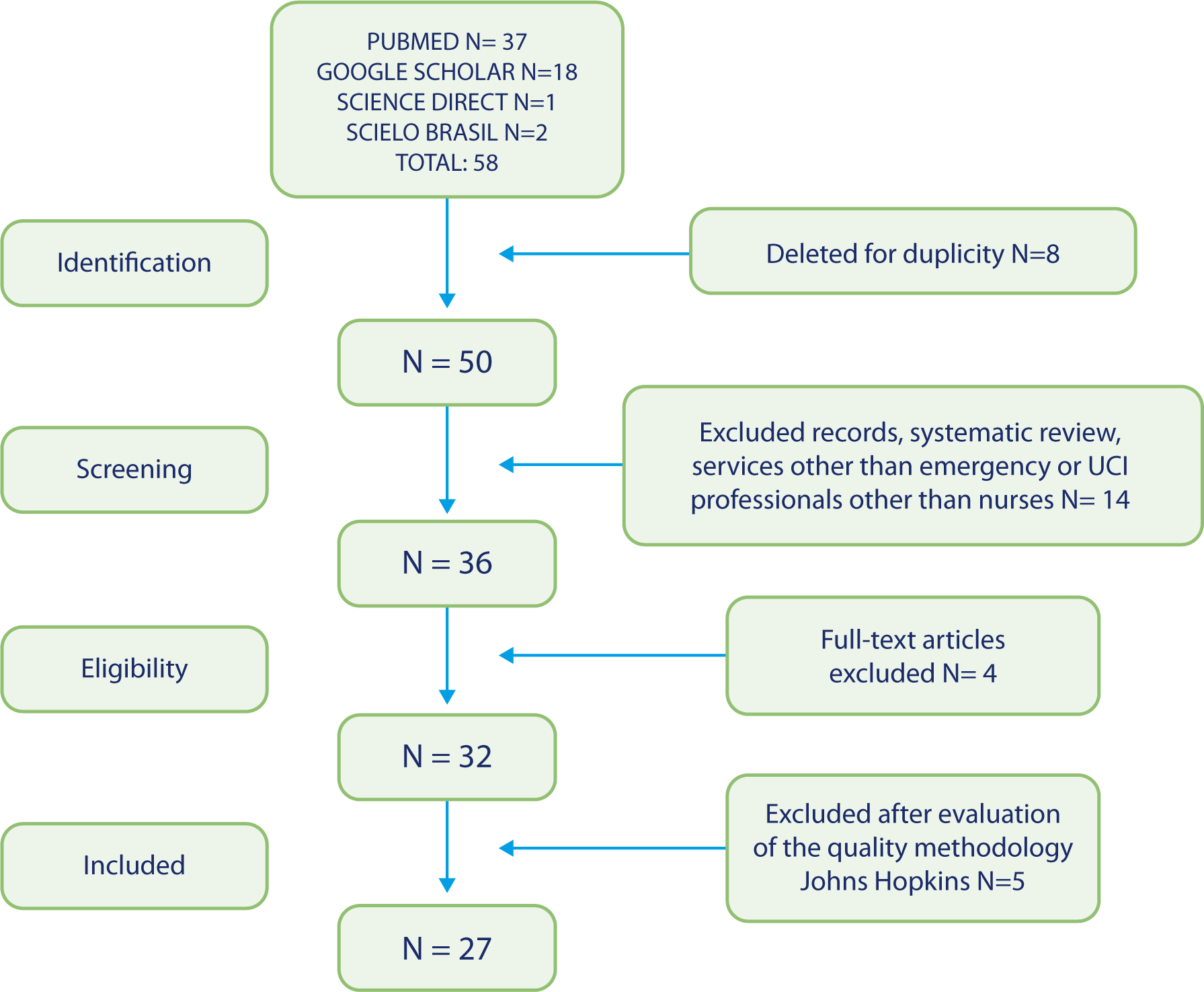

We started the selection of articles by reading titles and abstracts, and we initially located 58 primary reviews. After considering compliance with the previously mentioned criteria and eliminating duplicates, a total of 50 articles were gathered for an in-depth reading.

Out of the 50 articles assessed, 14 were dismissed because they failed to meet the inclusion criteria. Four were discarded following a comprehensive read-through, leaving 32 articles for analysis using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice tool. This tool allows for the identification of the type of evidence -whether quantitative or qualitative, as well as potential biases and the quality of the evidence. The tool features several sections; however, due to the systematic nature of the literature investigation, only sections E and G, which assess quantitative evidence, were considered. Section E appraised the purpose, bibliography, sample, instrument validity, results, and limitations of the selected articles.

In contrast, section G evaluated the author, publication date, evidence type, sample type, author's observations, limitations, quality level, and data summarized in Table 2. Upon concluding this evaluation, it was found that five studies were of subpar quality, leading to their exclusion. Consequently, only 27 studies were reviewed for the construction of the selection summary table.

The information gleaned from the reviewed articles was organized in an Excel spreadsheet. The details recorded included the author, country, year, objective, sample, methodology, results, limitations, and quality level of each article. This study received approval from the Committee on Ethics for Research in Human Beings (CEISH) at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Ecuador (Code: EXE-009-2023).

Table 1 Terms Combined with the Boolean Operators AND, OR, and NOT

| DeSC (Portuguese) | MeSH (English) | Dict. (Spanish) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Strategy | No | Strategy | No | Strategy |

| 1 | "Musculoskeletal Doenças" AND "Nurses" | 1 | ("Musculoskeletal Diseases" [ Mesh]) AND "Nurses" [Mesh] | 1 | "Musculoskeletal diseases" and "Nurses" |

| 2 | "Equipe de Enfermagem" AND "Condições de Trabalho" AND "Doenças Osteomusculares" OR Distúrbios Osteomusculares | 2 | ("Nursing Staff" [Mesh]) AND "Working Conditions" [Mesh] AND "Musculoskeletal Diseases" [Mesh] OR Musculoskeletal Disorders | 2 | "Nursing staff" AND "Working conditions" AND "Musculoskeletal diseases" OR Musculoskeletal disorders |

| 3 | "Doenças Osteomusculares " AND "Nurses" AND "Intensive Care Units" | 3 | ("Musculoskeletal Diseases" [ Mesh]) AND "Nurses" [Mesh] AND "Intensive Care Units" [Mesh] | 3 | "Musculoskeletal diseases" AND "Nurses" AND "Intensive care units" |

| 4 | Osteomuscular Doenças " AND "Nursing Equipment" AND related to work | 4 | (("Musculoskeletal Diseases" [ Mesh])) AND "Nursing Staff" [Mesh] AND work-related | 4 | "Musculoskeletal diseases" AND "Nursing staff" AND work-related |

| 5 | "Nursing Equipment" AND "Working Conditions" | 5 | ("Nursing Staff" [ Mesh]) AND "Working Conditions" [Mesh] | 5 | "Nursing staff" and "Working conditions" |

| 6 | ("Emergência Enfermagem") AND " Osteomuscular Doenças " AND related to work | 6 | ("Emergency Nursing" [ Mesh]) AND "Musculoskeletal Diseases" [Mesh] AND work-related | 6 | "Emergency Nursing" and "Musculoskeletal Diseases" and work-related diseases |

| 7 | "Intensive Care Units" AND "Nurses" AND " Osteomuscular Doenças " AND related to work | 7 | ("Intensive Care Units" [ Mesh]) AND "Nurses" [Mesh] AND "Musculoskeletal Diseases" [Mesh] AND work-related | 7 | "Intensive Care Units" AND "Nurses" AND "Musculoskeletal Diseases" AND work-related |

| 8 | "Dor lombar" OR "Doença do intervertebral disc" [Supplementary Conceit] E "Nurses" | 8 | "Low Back Pain" [ Mesh] OR "Intervertebral disc disease" [Supplementary Concept] AND "Nurses" [Mesh] | 8 | "Lower back pain" or "Intervertebral disc disease" [Complementary concept] and "Nurses" |

| 9 | "Excess weight" AND "Musculoskeletal disorders" AND "Nurses" | 9 | "Overweight" [ Mesh] AND "Musculoskeletal Diseases" [Mesh] AND "Nurses" [Mesh] | 9 | "Overweight" and "Musculoskeletal diseases" and "Nurses" |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the PRISMA standards.

Figure 1 Methodological Quality Evaluation

Table 2 Summary of Peer-Reviewed Scientific Articles

| Article | Author, Year, Country, Language | Quality Assessment | Method | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article 1 | Lilia Rodarte Cuevas, Mexico, 2016, Spanish19. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional, descriptive correlational | -Musculoskeletal conditions in most professionals -It affects the quality of life |

| Article 2 | Rosa Haydee Acosta, Argentina, 2022, Spanish20. | Level III, good quality | Observational, descriptive, cross-sectional | -Injuries to neck, back, ankles. -77% environmental, psychosocial, ergonomic, and chemical risks |

| Article 3 | Thais Pereira Días da Silva, Brazil, 2017, Portuguese 21. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -86.24% cervical, thoracic, lumbar spine -Related to fatigue -Decreases work capacity |

| Article 4 | Carvajal Vera C, Ecuador, 2019, Spanish10. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional and analytical | -Back, neck, and shoulder conditions -Psychosocial risks: reward mastery, social relationships, home-work displacement |

| Article 5 | Maria del Refugio Davila Troncoso, Mexico, 2020, Spanish22. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional and analytical | -Injuries to the neck, shoulder, wrist, lower limbs, lower back pain, joints -Factors: uneven ground, poor working conditions |

| Article 6 | Alba Maria Sanabria Leon, Colombia, 2015, Spanish23. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional with analytical exploration | -Low back pain associated with biomechanical factors |

| Article 7 | Amparo Astrid Montalvo Prieto, Colombia, 2015, Spanish24. | Level III, high quality | Descriptive analytical | -49 5% back and neck conditions. Association of physical workload |

| Article 8 | Ma. Rosy, Mexico, 2019, Spanish25. | Level III, good quality | Observational, descriptive, prospective and cross-sectional | -Injuries to neck, lower back, knees. Higher risk morning shift |

| Article 9 | Aimé Ruth Ballena Ramos, Peru, 2021, Spanish26. | Level III, good quality | Non-experimental, descriptive and cross-sectional | -Cervical, dorsal, and lumbar conditions. Women higher prevalence. Routine activities |

| Article 10 | Man-Hua Yang, Taiwan, 2022, English 27. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional | Greater lumbar involvement. Factors: exercise habits, chronic diseases, little time to rest |

| Article 11 | Ahmad Bazazana, Iran, 2019, English28. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Problems with knees, back, neck and shoulders. -Risks: schedule, satisfaction levels, workload |

| Article 12 | Zulamar Aguiar Cargnin, Brazil, 2019, Portuguese 29. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional | -Back pain due to factors: space, productivity, physical environment, equipment and instruments |

| Article 13 | Seyed Ehsan Samaeia, Iran, 2016, English30. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional | -69.5% low back pain -Relationships between age, hours, experience, body mass (BMI), gender, shifts |

| Article 14 | Mireya Zamora Macorra, Mexico, 2019, English31. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Neck and lumbar injuries -Ergonomic factors, exposure time, work at home |

| Article 15 | Thanh Hai Nguyen, Vietnam,2020, English 32. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Injuries to the back, neck, shoulders, upper limbs -Prevalence increased with age, background, urban areas |

| Article 16 | Shuai Yang, China, 2019, English33. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional | -Lumbar, neck and shoulder injuries -Factors: being a woman, single, lack of a safe work environment |

| Article 17 | Brightlin Nithis Dhas, Qatar, 2022, English 34. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Lumbar, neck, shoulder injury -Related to age, educational level, service |

| Article 18 | Hanif Abdul Rahman, Brunei, 2017, English35. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional | -Psychosocial factors: work-family conflict, stress, exhaustion |

| Article 19 | Semira Mehralizadeha, Iran, 2016, English36. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional | -Psychological factors, working posture, individual factors |

| Article 20 | Yongcheng Yao, China,2019, English37. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Neck, waist, and shoulder conditions -Factors: lack of exercise, night shifts, lack of sleep |

| Article 21 | Roberto Latina, Italy, 2020, English38. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Lumbar conditions -Higher risk female sex |

| Article 22 | Khader A, Jordan, 2020, English39. | Level III, high quality | Cross-sectional | -Predictive conditions: being a woman, lack of sleep, physical activity, ergonomic deficit, workload and stress -Neck, back, shoulders, wrists, hands and elbows conditions |

| Article 23 | M. Chiwaridzo, Harare,2018, English40. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Lumbar condition -Factors: qualification obtained, ergonomic training and work experience |

| Article 24 | Hashem Abu Tariaha, Saudi Arabia, 2019, English 41. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Lumbar, shoulder and back injury -Factors: deficiencies in ergonomic and work conditions, lack of body mechanics |

| Article 25 | Elahe Hosseini, Iran, 2021, English42. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Ankle, lumbar, knee, and shoulder conditions -Factors: age, service, rotating shifts |

| Article 26 | Rafael de Souza Petersena, Brazil, 2017, Portuguese 43. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Higher risk for technical personnel and female gender |

| Article 27 | Zulamar Aguiar Cargnin, Brazil, 2020, Portuguese 44. | Level III, good quality | Cross-sectional | -Lumbar injury associated with other diseases and psychosocial and psychological factors |

Note: The articles presented in this table allowed us to identify the factors associated with musculoskeletal disorders, as well as to know the anatomical part most affected and that causes discomfort in nursing professionals.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Results

S Regarding the methodological characteristics of the analyzed studies, they were cross-sectional and conducted in various parts of the ¿ world. On the American continent (Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru), 13 works were recorded; in Asia (China, 4 Iran, Vietnam, Qatar, Brunei, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia), there were y 12 articles, and in both Europe (Italy) and Africa (Harare), only one z study each was selected. As for the year of publication, it was noted that most of the articles (n = 18) were published from 2019 to 2022, while there were nine published from 2015 to 2018.

Concerning sociodemographic factors, the participants in each study were primarily women (more than 60%), with an average age ranging from 31 to 35 years. Most were married and held a bachelor's degree in Nursing, followed by a nursing assistant certification. As for their years of service, the vast majority had worked for less than 10 years.

Table 3 Sociodemographic Factors

| Article | Age | Sex | Marital Status % | Study Level % | Years Of Service | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female% | Male% | Married°/o | Single/ | Bachelor's Degree% | Assistant% | Technical% | |||

| Article 1 | 34 | 75 | 25 | 44 | 28 | 46 | 3.7 | 9 | |

| Article 2 | 43 | 70 | 30 | 48 | 26 | 25 | 2.5 | 73 | 14 |

| Article 3 | 39 | 90 | 10 | 62 | 23 | 1 to 10 | |||

| Article 4 | 36 | 89 | 11 | 47 | 37 | 59 | 1 to 5 | ||

| Article 5 | 25 | 80 | 20 | 82 | 18 | 40 | 1 to 9 | ||

| Article 6 | 34 | 80 | 20 | 26 | 46 | 23 | 71 | ||

| Article 7 | 30 | 85 | 15 | 19 | 74 | < 2 | |||

| Article 8 | 25 | 81 | 19 | 53 | 28 | ||||

| Article 9 | 73 | 27 | 22 | <1 | |||||

| Article 10 | 44 | 90 | 10 | 6 | |||||

| Article 11 | 34 | 67 | 33 | 82 | 10 | ||||

| Article 12 | 41 | 83 | 17 | 66 | 21 | 79 | 1 to 4 | ||

| Article 13 | 30 | 88 | 12 | 81 | 19 | 12 | 23 | 65 | < 10 |

| Article 14 | 41 | 94 | 6 | 35 | 51 | 16 | |||

| Article 15 | 32 | 81 | 21 | 1 | |||||

| Article 16 | 28 | 89 | 12 | 56 | 44 | 80 | 20 | 6 | |

| Article 17 | 35 | 100 | 92 | 8 | 13 | ||||

| Article 18 | 35 | 70 | 30 | 69 | 31 | 75 | 25 | 10 | |

| Article 19 | |||||||||

| Article 20 | 28 | 95 | 5 | 7 | |||||

| Article 21 | 43 | 75 | 25 | 58 | 14 | ||||

| Article 22 | 32 | 53 | 47 | 9 | |||||

| Article 23 | 32 | 85 | 15 | 69 | 31 | 88 | 12 | 7 | |

| Article 24 | 30 | 98 | 2 | 15 | |||||

| Article 25 | 31 | 78 | 22 | 56 | 44 | ||||

| Article 26 | 42 | 89 | 11 | 61 | 25 | 7 | 68 | ||

| Article 27 | 35 | 83 | 17 | 67 | 23 | ||||

Source: Prepared by the authors.

The anatomical regions where musculoskeletal disorders most frequently occurred were the lumbar region, reported in 23 out of 27 articles, followed by the neck, cited in 18 reviews, and shoulders, indicated in 11 studies. In the vast majority of cases (14 articles), the discomfort began during working hours at the different institutions.

Table 4 Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders according to Different Anatomical Parts

| Variable | Articles |

|---|---|

| Lumbar | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 27 |

| Neck | 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, 25 |

| Shoulders | 3, 4, 5, 12, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, 24, 27 |

| Spine | 1, 3, 4, 7, 9, 11 |

| Legs | 2, 3, 5, 11, 25 |

| Hip | 8, 12, 19, 27 |

| Arms | 3, 15, 18 |

| Knees | 1, 4, 8 |

| High back | 22, 24 |

| Joints | 5, 27 |

| Feet | 2, 4 |

| Head | 3 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Concerning the factors associated with the incidence of musculoskeletal conditions, it was observed that nursing professionals were at a greater risk of developing these disorders when performing mechanical movements such as: lifting heavy weights, making repetitive movements, or maintaining unsuitable postures. This was closely followed by factors like high job demand and both physical and workplace environments within their institutions.

Table 5 Factors Associated with the Presence of Musculoskeletal Disorders

| Variable | Articles |

|---|---|

| High labor demand | 1, 4, 5, 10, 12, 14, 15, 16, 10, 20, 21, 23, 26, 27 |

| Mechanical risks | 2, 4, 6, 7, 13, 14, 19, 20, 21, 23, 26 |

| Work environment | 2, 12, 16, 18, 19, 21, 27 |

| Less rest time | 2, 3, 10, 16, 20, 21 |

| Professional relationships | 5, 22, 25, 26, 27 |

| Frustration | 11, 12, 19, 22, 27 |

| Physical risks | 2, 4, 10, 12, 13 |

| Distribution of equipment and furniture | 2, 12, 13, 16 |

| Biological risks | 2, 4, 12 |

| Sex | 21, 26 |

| Leadership | 4, 18 |

| Lack of management support | 1, 12 |

| Chemical risks | 4 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Discussion

This research evaluated the results of published studies on factors associated with musculoskeletal disorders in nursing professionals working in critical areas. The conclusions suggest that, regardless of geographical location, all health professionals exhibit the same ailments 45.

Among the characteristics noted in the selected studies, the standout is their heterogeneity -namely, the demographic and social diversity within the study population. The articles that were useful for the systematic review of the literature were sourced from various continents: America, Asia, Europe, and Africa. These regions exhibit differing characteristics in habits, customs, and the academic training of nursing professionals. Nevertheless, across all regions, it was observed that these professionals suffer from musculoskeletal conditions. Hence, nursing is one of the professions requiring the utmost dedication and susceptibility to physical wear and tear.

In their study, Marín and González described results akin to those discussed in this literature review, focusing on the sociodemographic elements of nursing staff. They emphasize that the majority are female, possess a bachelor's degree, and have less than 10 years of seniority in service 46. This research indicates that, even in this modern era, the nursing career is still predominantly viewed as a female profession, which partly explains the high incidence in results. Furthermore, it demonstrates that these pathologies can emerge early in the profession, impacting both personal and work life.

After reviewing the articles for this research, we discovered that nursing professionals often experience muscle conditions in two or more body parts, primarily in the lumbar region, neck, and shoulders. Similar findings were presented in other research, noting that the anatomical areas with the most pain were the neck (94.1%), lower back (88.2%), shoulders (64.7%), and forearm or elbow (18.8%) 47. Considering these results, it can be inferred that these conditions in different anatomical areas could be due to the physical and repetitive nature of daily tasks performed by nursing professionals.

She also noted that musculoskeletal symptoms in nurses have a high prevalence at the lumbar level in both men and women 48. However, women also experience pain at the cervical/neck, shoulder, wrist, and ankle/foot levels. For the review conducted, it should be considered that, due to their physical structure, women are at a disadvantage compared to men. In this sense, the demand for physical strength implies a certain vulnerability for them.

The studies examined identified that the nursing staff exhibited increased in-hospital risks due to repetitive mechanical movements, patient position changes, heavy lifting, and forced postures-tasks highly linked to musculoskeletal disorders 49. This is in line with a study conducted by Vásquez, stating that 76.5% of nurses perform some type of manual handling of hefty loads, 94.1% execute repetitive movements, and 100% maintain forced postures 47. These conditions heighten the odds of presenting muscular ailments in their occupational performance.

Similar results were described in the research by Serranheira et al., pertaining to musculoskeletal conditions and the varying body positions adopted by nursing staff throughout their workday. This includes mobilizing, lifting, and transporting loads/patients weighing more than 20 kg, which generates a higher vulnerability 50.

Following the above, this research should be a significant resource for the scientific health community, particularly nursing, to bolster these professionals, protect their well-being, and enhance daily performance. The results discussed hold substantial value for implementing a best practices protocol for nursing staff. We daresay this knowledge could even fuel public policies to ameliorate the current situation of these professionals, by revising work hours and the number of nurses employed across various health institutions, thereby avoiding such disorders.

Limitations

While the results obtained meet the objectives outlined in this systematic review, it may be beneficial not to limit the search to articles in Spanish, English, and Portuguese for better information and an expanded research perspective. The timeline and level of quality served as limiting factors; several articles were omitted based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Another limitation was the inaccessibility of a large number of studies from the global scientific community due to their high consultation costs. As a result, certain valuable documents were set aside, which likely contained pertinent information for this analysis. It is worth noting that nearly no information was found on the subject during the process of this review, which constrained the work. Nonetheless, this paper paves the way for future research on the topic.

Conclusions

Based on a systematic literature review of scientific articles on musculoskeletal disorders affecting nursing staff in critical care areas, it was found that the majority of research participants were female, aged 31 to 35 years. This could explain the persistent perception that nursing is a profession exclusive to women.

The risk factors identified in the analyzed studies indicated that nursing staff, due to their involvement in mechanical and repetitive patient care movements, presented a higher in-hospital risk for musculoskeletal disorders.

The anatomical regions most commonly affected by disorders were the lumbar area, neck, and shoulders. A vast majority of these health issues began during the professional workday across different institutions, thereby indicating a high prevalence.

Regarding the geographical diversity of the reviewed articles, it was determined that despite the unique characteristics of each country concerning the nursing profession, the presence of musculoskeletal conditions in healthcare personnel is less dependent on location and more on the role of the nursing profession within the health team.

Public health strategies and policies are required to promote the prevention and control of musculoskeletal disorders among nursing staff. These initiatives must be grounded in scientific research about such diseases and the everyday practices of nursing.