Introduction

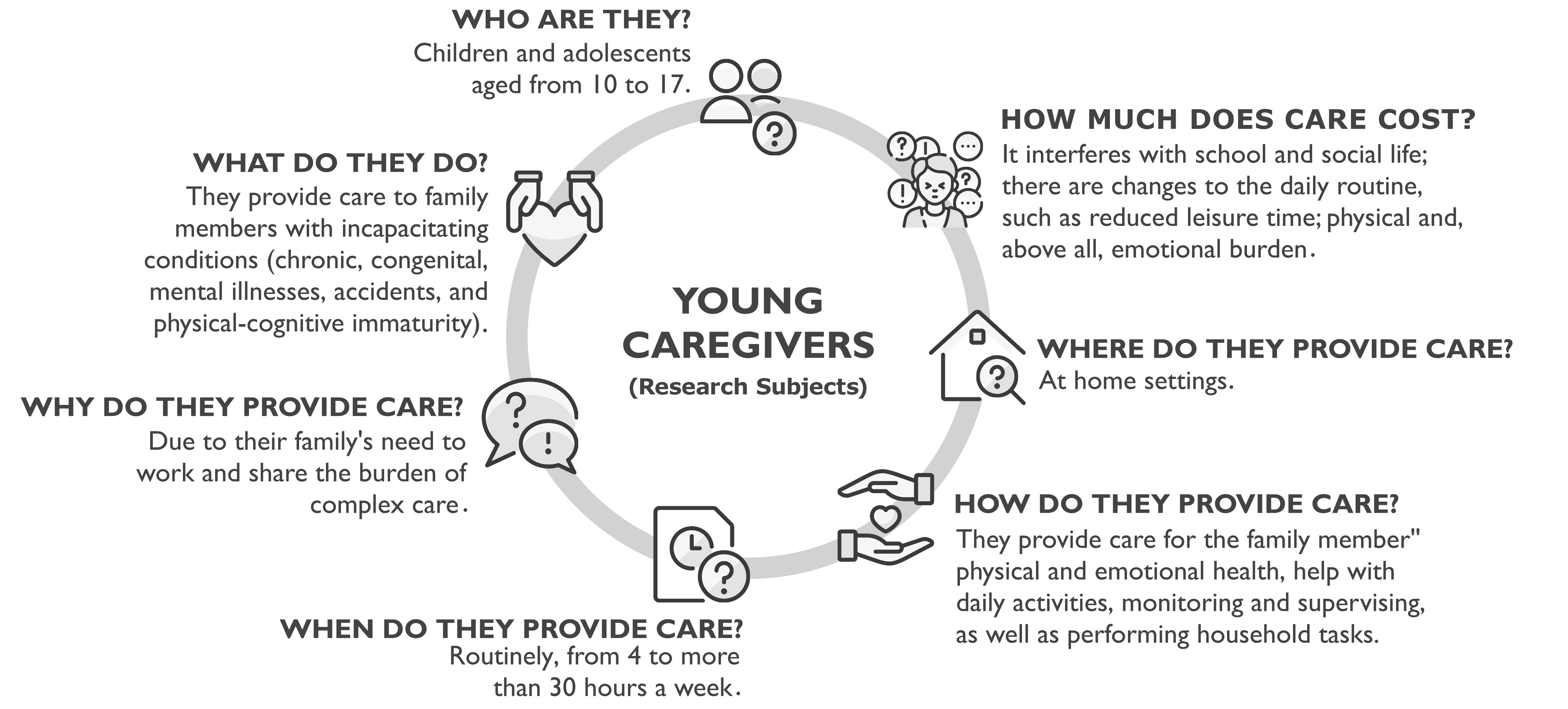

Individuals under the age of 18 who assume family care responsibilities beyond what is typically expected for their age and who perform activities usually attributed to adults are referred to as 'young caregivers' 1-3. Although no official numbers exist, it can be noted that several of these young caregivers find themselves tasked with providing care to a family member, especially parents, grandparents, or siblings, who have some condition that requires care, such as chronic and mental illnesses, disabilities, or physical-cognitive immaturity 1,4,5.

Young caregivers can help with medical care, provide emotional and personal support, help with household chores, or educate younger siblings 4,5. However, unlike adult caregivers, young caregivers assume these responsibilities but are unrecognized 5, often remaining invisible to the community 3.

Without adequate support and in the absence of the necessary resources, these young individuals can experience situations that interfere, in the short and long term, with their physical and emotional health 6-8, as they are unable to fully engage in activities that are essential for their academic, professional, social, and personal development 7,9.

Young caregivers spend hours providing care to a family member without compensation. Although this contributes to the family economy and, consequently, reduces costs for the healthcare system 9, it can be noted that, to date, there has been no form of support implemented or dedicated to this population, which is intensely affected by the responsibilities assigned to them 10.

The care provided by this population can be understood as a complex process due to its multidimensionality; its effects and meanings can transcend the mere attribution of 'caregiver' 11,12. Assigning the care of dependent family members to young caregivers evokes contradictory perceptions and feelings, such as certainties and uncertainties, order and disorder, characterizing a complex phenomenon of interrelationships/interactions between the elements and their realities 12.

It is worth noting the data found in the literature is insufficient-there are limited reports on young caregivers in the setting of providing care to their family members or care-dependent people 11.

It is also considered that the studies found lack a substantive theory for the central phenomenon under study.

Therefore, the need for this study is justified to clarify the complexity surrounding the phenomenon of being a young caregiver and to provide support for the improvement of this care practice. The aim was to understand how young caregivers perceive providing care to a family member who depends on them.

Materials and Methods

This is an exploratory, qualitative study that adopted complex thinking 12 as its theoretical framework and data-based theory, from Strauss' perspective 13, as its methodological framework. This theory was selected due to its potential to achieve a deeper and more contextualized understanding of the social phenomena under analysis. The Straussian approach to data-based theory is particularly suitable, as it allows for literature consultation at all stages of the research. In addition, its rigorous coding system guides the researcher through all the stages of data analysis, facilitating the development of a solid theory based on the experiences of the subjects under study.

The research setting consisted of the households of young people % and family members who were providing care to a care-dependent | family member, residents of Maringá, a municipality located in the northwestern region of Paraná, Brazil. Data was collected from August 2022 to October 2023. This process was conducted by applying several instruments, the content of which was validated by three specialists in the field of child and adolescent health before data collection started.

The collection instruments included sociodemographic questionnaires; semi-structured scripts for face-to-face interviews (Appendix); unstructured observations, and tools for internal analysis of the family configuration, such as genograms, and for external analysis of the family environment, such as ecomaps.

The research was conducted using two sample groups. The first group, consisting of 15 young caregivers, was selected due to their role in the phenomenon under study. The second group, consisting of seven family caregivers, was selected based on the data emerging from the initial members' reports. These family members were people who lived with the young caregivers and were their legal guardians and responsible for the care of these children and adolescents. It should be noted that the total number of participants in each sample group was consolidated once theoretical saturation had been reached.

The selection criteria for the first sample group included: being a child or adolescent under the age of 18 who provides care, assistance, or support to a family member in need of care; performing activities such as health care, daily activities, domestic and/or socio-emotional assistance, and not being a mother or father responsible for the care of younger children. For the second sample group, the inclusion criteria included being legally responsible for the young caregiver and being the care coordinator in the family setting.

In light of the invisibility of young caregivers and the hidden circumstances in which they live, community healthcare workers from each of the city's Basic Healthcare Units and Family Healthcare Support Units were requested to assist in identifying this population. Finally, 38 healthcare services were contacted, including the Home Care Service (HCS).

The interviews were conducted simultaneously with the data analysis and the composition of the sample groups. A total of 7 hours and 25 minutes of interviews were analyzed, which were audio-recorded for an average of 20 minutes and then transcribed. It should be noted that the field diary notes were included in the analysis process. The statements went through a process of linguistic normalization to reduce the informality of colloquial expressions. Data analysis was guided by three stages: open, axial, and selective coding.

The interviews from both sample groups were read in detail in open coding, followed by the creation of codes to represent the concepts stemming from the data. Subsequently, during axial coding, the open codes were compiled by conceptual affinity, forming code groups, which favored the construction of categories and subcategories. In the last stage, referred to as selective coding, the categories were refined, and the core phenomenon was elaborated.

During the analytical process, memos and diagrams were used to facilitate understanding and structuring of the theoretical model. It should also be noted that the ATLAS.ti® software was used in the analysis as an organizational and data optimization tool.

Finally, the theoretical framework was validated by four participants, two from each sample group. This step is essential to confer credibility and reliability to the data, ensuring the scientific rigor of the study by following all the methodological steps. During this step, it was found that no significant changes needed to be implemented in the proposed model, given that the participants recognized most of what had been drafted. It should also be noted that this study followed all the guidelines of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guide.

The research was approved by the Standing Committee on Ethics in Research with Human Beings of the State University of Maringá, under opinion 5.707.802 and certificate of submission for ethical appraisal 61476022.1.0000.0104. The participants were referred to in the study as 'young caregiver' or 'family member,' followed by the corresponding number in the order in which the interview was conducted.

Results

A total of 22 individuals participated in the study, comprising two sample groups: the first of young caregivers, with 15 interviewees, and the second with seven family members, who were the legal guardians of eight of the young people in the first group. Regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of the young caregivers, it was found that eight were female, with a mean age of 13 and a range from 10 to 17 years of age. Ten were of mixed race/color, 13 attended elementary school, and seven had a family income of up to two times the minimum wage.

In addition, the family bond with the care-dependent person was predominantly that of siblings, with seven cases, followed by parents, with four cases, and grandparents/great-grandparents, also with four cases; of these, seven reported having dedicated more than 30 hours a week to providing care. Regarding the reasons that led to dependence on family care, there were multiple reasons, such as the presence of chronic, congenital, and mental conditions, accidents, and physical and cognitive immaturity.

Regarding the characteristics of the family members who were the legal guardians of the young caregivers, six were female, corresponding to four mothers and two grandmothers, and only one participant was male, who was the young caregiver's J uncle. Their ages ranged from 40 to 49 years, with five participants of mixed race/color. The prevailing per capita income consisted of up to half the minimum wage, and five had a salary at the time of the interview.

After analyzing the reports, the following thematic categories were formulated: "When the need to provide care suddenly becomes a reality;" "Becoming a young caregiver: lived experiences;" "The daily life of a young caregiver: types of care, expectations, and perceptions."

When the Need to Provide Care Suddenly Becomes a Reality

Identifying the lived reality of the young caregivers permitted clearly visualizing the costs related to physical, emotional and social aspects. Those results are presented in the fragments of substantive theory, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Becoming a Young Caregiver: Lived Experiences

It was noted that the transition to the role of young caregiver was often prompted by unforeseen events, such as the onset of illness in a family member, the outbreak of a global pandemic, as was recently the case with the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), an accident, or even the birth of a sibling, a factor that can trigger the need to assume additional care responsibilities.

I started providing care when he [great-grandfather] became bedridden, and from then on, he walked very little [...]. He couldn't walk anymore from October onwards, after his fourth stroke. (Young caregiver 10)

In addition to these circumstances, it was noted that most of the time the responsible family members had to share the care responsibilities due to their work obligations and the fact that they were the main income providers in the household. Furthermore, it was found that in some cases care was distributed to share the burden of activities, especially in cases where care was more complex.

I was living with my mother, so when my grandmother got COVID, she got really bad. My uncle worked and so she needed someone, right? There was no one else available, so I moved here to help. (Young caregiver 1)

We split up into teams to look after him [brother]. So, in the morning it's my mother, and in the afternoon it's me. Sometimes at weekends and in the evenings, it's me too. (Young caregiver 9)

Despite the inherent challenges, it was noted that the young caregivers behaved differently when they assumed responsibility for providing care to their family member. Some young people were proactive in performing care activities, while others reported that care was gradually incorporated into their daily routine.

I learned to administer insulin by myself. My grandmother was administering it once and I said: "Let me administer it", so I learned on my own. (Young caregiver 10)

I think that when my grandmother was in hospital it was much more tiring [...]. Now it's normal. I've gotten used to it, it has become part of my routine. (Young caregiver 8)

Regarding the recognition process of becoming a young caregiver, it was possible to find that those who were born and raised in a care environment tended to identify themselves as caregivers since childhood, expressing spontaneity in assuming domestic and healthcare tasks. The same group also found it difficult to identify themselves as caregivers, especially in the case of caregivers of older siblings who had congenital diseases, as they claimed that this was normal in the context in which they were living.

Oh, basically, I always took care of him, because my grandfather, before he passed away, was a wheelchair user. The only reason I didn't give him his medication and things like that was because I didn't know how to read yet, because I was still a child. But I took him places, cleaned the house, helped him do things [...]. I've always been a caregiver, so there’s no milestone, like before and after. (Young caregiver 8)

In contrast, the young caregivers who were abruptly inserted into a care scenario, usually those who were assisting adult or elderly relatives, expressed feelings of strangeness and incipience that they would be placed in this position.

[...] for me, I never... Like, I didn't imagine I'd go through this, you know? (Young caregiver 10)

He helps me a lot, but I don't charge him much. Because he feels so bad. He does it, but I feel he doesn't like it. (Family member 3-Young caregiver 4)

It can be gathered from the interviews presented that the experience of becoming a young caregiver is unique and each person will have a different perception of it, depending on the context (current and previous) in which they are inserted.

The Daily Life of a Young Caregiver: Types of Care, Expectations, and Perceptions

It was noted that all the young people assumed more than one caregiving role, with four participants performing activities that ranged from healthcare to household chores. The most outstanding tasks included providing care focused on the family member's physical health (administering medication, monitoring blood glucose levels, wound dressing, assisting with mobility, and handling invasive devices, such as tracheostomies and gastrostomies, among others), providing care related to the family member's emotional health (providing support, keeping the family company, performing recreational activities, and going for walks with the family member, among others), and supervising and monitoring care.

I take care of him, I help my mother bathe him [brother], I help to suction when needed, I help to change him when needed. I give him milk, medicine, I do everything. (Young caregiver 9)

Other types of care mentioned include care in daily activities (participating in decisions concerning health care, providing guidance on an adequate lifestyle, among others), and care involving domestic activities (organizing and upkeeping the household, and preparing meals for the family).

I sort out the medication, I clean the house for her [grandmother], I make food, I take her to places, I do the shopping, I talk to her... I do everything. I used to do her wound dressing. (Young caregiver 8)

Some participants reported that caregiving makes daily life difficult, as excessive demands and constant concern for the family member's needs can override private priorities, which can result in sleep deprivation, and disruptions to their appointments, projects, and personal dreams.

Then, after he [great-grandfather] got sick, he called me in for everything. Then everything gets delayed, you know? If we're washing the dishes, we have to stop and go and see him. Then as soon as we turn our backs, he's calling again. So, it gets in the way a bit, doesn't it? (Young caregiver 10)

It also became clear that assuming the role of being a young caregiver interferes with school activities, as it impairs the performance of actions within the family setting and hinders going to and back from school.

I'm in 9th grade, I'm attending YAE [Youth and Adult Education], because I wasn't able to go to school very often before, since I was looking after my grandfather and my nephew. (Young caregiver 8)

[...] while I was all alone, I was desperate. But then she [the young caregiver] quit school. So, at the beginning of the month, she studied in the morning and at night to try and catch up a bit. (Family member 7-Young caregiver 8)

I can't perform very well in exams; my grades are low because I can't balance my responsibilities at home. (Young caregiver 15)

In addition, it was noted that although there were challenges in achieving good school performance, most of the young caregivers enjoyed going to school, as they also perceived this environment as a social and leisure space.

I think that's my place of peace. I think I'd rather be at school than at home. Because it seems that everything is easier at school, right? (Young caregiver 10)

I like school because my friends are there. (Young caregiver 7)

It was also clear that the changes in the young caregiver's daily routine, stemming from the demands of caregiving, interfered with s their relationships with peers and limited their leisure opportunities, reducing or even preventing them from participating in recreational activities.

It's just that before I didn't use to do anything, right? I stayed out playing with my friends... now things have changed because I have to look after her [grandmother]. (Young caregiver 1)

Even the girls don't have any leisure time, because she [the young caregiver] is 14, so if we don't go out, she won't either [...]. We don't really have any leisure time. (Family member 5-Young caregiver 15)

The emotional complexity experienced by the young caregivers was expressed in ambiguous feelings, ranging from satisfaction and fulfillment stemming from the act of caregiving to negative emotions such as stress, distress, frustration, impotence, and sadness over the family member's condition. It should also be noted that the genogram analysis showed that most of the young people lived in single-parent or blended families, a factor that has the potential to intensify the emotional insecurities of these individuals.

I think it's a bit bad because I'm still too young to have this responsibility to help my mother look after her. It's not that I don't want to, but because it's my mother's and father's role to do this. And now I'm assuming the role of father and it's £ stressful. (Young caregiver 13)

[...] my mother abandoned me and my two brothers. There were four of us. Then she took the youngest, who wasn't even a year old, and left us behind. (Young caregiver 10)

The limited life prospects of an ill family member were perceived as intensifying negative emotions. In this context, the anticipation of the loss and the bereavement process for the ill family member was noticeable in the participants' speeches. It is worth noting that some young caregivers also showed a feeling of functional loss of the family member, a process known as "unrecognized bereavement," since although they had the family member physically present there, psychologically they were absent.

I usually say: "God gave us Bro [brother dependent on care], but just as I'm going to die, Bro will too." So, I'm preparing them [daughters-young caregivers]. (Family member 2-young caregiver 9)

[...] whether you like it or not, you're going to miss him. Like, at the [school] meeting, I always say that my grandfather is my father [care-dependent father]. (Young caregiver 5)

However, it is worth noting that this experience can also have positive aspects. Several young caregivers reported developing feelings of confidence, courage, satisfaction, personal growth, and stronger family ties as a result of their care responsibilities.

A lot has changed since I started looking after him. I'm different. I was more of a child before. Now I feel responsible for the things I do. (Young caregiver 15)

Oh, I feel good, because when I was younger, he [father] changed my diapers, took care of me, gave me water, gave me food. I feel like I'm doing the same for him. (Young caregiver 5)

In light of this scenario, it can be understood that there is a range of feelings that permeate the journey of a young caregiver. Reconciling these feelings with the experiences of providing care to a family member, in which there are strongly established emotional bonds, can become complex and challenging, given the personal and contextual uncertainties.

Discussion

The results revealed that becoming a young caregiver is something that can occur unexpectedly, directly interfering with various aspects of a young person's life. The literature shows that the population of young caregivers is not fully recognized in society, especially in Brazil, leading them to live in seclusion and have their needs suppressed 14.

It is known that the impact of perceiving oneself as a caregiver at such an early stage generates conflicting feelings that are often permeated by external influences that are difficult to control. Such events can impose early maturation and the acceptance of responsibilities which, for the most part, are typically adult in nature 1,15. Among the roles performed by young caregivers is that of primary, secondary, tertiary, and/or auxiliary caregiver, relating directly and/or indirectly to the family member being cared for 2. In this study, the acceptance of roles that were interconnected for the most part was evident, rendering it impossible to classify these caregivers in terms of the levels of care provided.

Becoming responsible for the care of a family member can be challenging, as it requires the caregiver to balance their needs with those of the individual under their care, given that this practice substantially interferes with daily life and, consequently, with the dimensions that permeate life and its relationships 7,16-18.

Providing care to a family member who is ill or unable to perform self-care, whether for pathological or physiological reasons, can also lead to an emotionally turbulent experience. Emotional burden can be exacerbated by a lack of social support, isolation, and the constant pressure to balance the responsibilities of care with the demands of daily life 19.

Meanwhile, it is clear that family disruption, such as the separation of parents and abandonment by parents, are also potential factors for emotional stress in the context surrounding young caregivers 20.

It should be noted that the time spent by young caregivers providing care to family members who need assistance showed a significant correlation with the school attendance and performance of these individuals, a fact also evidenced in the literature 21,22. It is known that the school environment is an essential setting for the development of children and adolescents and that formal education has a crucial role in character development, the construction of knowledge, and preparation for adult life 23.

When the school and teachers are aware of the condition of these children and adolescents, some young people are more supportive, while others report feelings of insensitivity, since the fact of being a caregiver in the maturation and training process has an impact on the adequate development of their studies and even on their understanding of the lessons and compliance with the requested activities 24.

Despite the difficulties and ambiguous relationships between young people and school, a large body of evidence suggests that adolescents and/or their families or legal guardians should notify the school and teachers of the role performed by the young person to optimize their performance. This is because when young caregivers are able to trust teachers, their performance and enjoyment of being at school improves considerably, although the basic psychological needs of these young people are not always met 25.

Another characteristic related to being a caregiver highlighted in this study is the change in routine resulting from the diagnosis since the family needs to reorganize itself. Roles are changed and many new ones are created. Despite providing the best care possible, the young caregivers, who until then had not performed such activities, also have to face the bereavement resulting from the rupture in the relationships they had with the family member and with the very organization of the nucleus before the onset of the illness. There is the grieving for dreams, for a future that until then had been structured, and the destruction of the belief that illnesses and serious situations only happen to other people, and not to their loved ones 26.

Notwithstanding the difficulties related to the process, some young people reported that they had matured during the experiences related to providing care to their loved ones, which contributed, in a way, to their growth and made the transition through the stages of life -being a child, then an adolescent, and then an adult- happen more quickly and meaningfully 19,27.

Finally, the results revealed a prevalence of young caregivers and family caregivers of mixed race/color, who are in conditions of socioeconomic vulnerability, with a per capita income equivalent to half the minimum wage. This context reflects the structural inequalities intrinsic to Brazilian society, where factors such as race and social class interact to perpetuate the exclusion and marginalization of certain groups.

The intersection of racial conditions and economic insecurity shows how social inequalities manifest themselves, limiting access to resources, healthcare services, and development opportunities. Furthermore, this reality highlights the need for public policies that address the particularities of these young people, considering not only their responsibilities as caregivers but also the structural barriers that impact their quality of life and well-being 28.

The absence of policies and measures to support healthcare services regarding young caregivers was highlighted in this study. This point warrants special attention, as such measures can help relieve the burden experienced and even work as a support network, in the sense of sharing the emotional burden and ensuring that these children and young people are able to experience the situations according to the age group in which they are inserted 29-31.

In this regard, the HCS should be mentioned, which is responsible for providing health promotion, prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliation at home, ensuring continuity of care for other points in the network 32. The HCS is part of the public policies present in the city under study, being implemented by Ordinance 825/2016, through the Better at Home program 33.

However, considering that the HCS was consulted during the first stage of data collection to identify the target population, it was found that this service recognized the presence of some young caregivers in home settings. However, it lacked specific intervention strategies aimed at this population, thus highlighting the marginalization of these individuals within the scope of healthcare services.

It was clear that the invisibility of young caregivers to healthcare services is a concrete reality, as is the numerous and equally veiled existence of these individuals. This population therefore requires more careful assistance from the healthcare team. To ignore their existence means contributing to the perpetuation of significant challenges, compromising not only their well-being but also the emotional and social balance of their families. This study highlights the urgent need for a paradigm shift from ignorance to acceptance and active support. It is therefore essential to plan and implement effective measures aimed at this population since professional intervention facilitates coping with the challenges experienced by young caregivers and family caregivers.

It is clear that the data cannot be generalized and portrays a local reality, which represents a study limitation. However, considering the scarcity of studies on the subject, this study is essential as it highlights the problems experienced by a population that is on the fringes of healthcare services, such as young caregivers.

Conclusions

This study showed that how young caregivers attribute meaning to providing care to a care-dependent family member is broad and permeated by ambiguous feelings since they simultaneously feel overwhelmed and ashamed of exercising this role and exposing it to other people, while also reporting maturity and an increase in technical, emotional, and social skills.

These young people experience a loss of autonomy, leisure, social interaction, and even a reduction in school attendance and activities. The findings of this study also highlight the structural inequalities that permeate society, where the interaction between race and social class perpetuates the exclusion and marginalization of this population. It is noteworthy that these caregivers are often neglected by healthcare services and do not receive the support and welcome they need to fully develop their adolescence process.

It is worth highlighting the need for more studies on the subject to devise strategies for reducing the family burden stemming from the care process, enabling these young people to balance their care responsibilities with their personal, social, and educational development needs.