Introduction

The first case of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was detected in December 2019 in China. Since the outbreak, millions of confirmed cases have been identified (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). Until May 24, 2023, the WHO had reported 766,895,075 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 6,935,889 deaths globally; in Mexico, 7,611,736 confirmed cases and 334,079 deaths had been registered (WHO, 2023). Moreover, the pandemic has had an impact on the subjective well-being of people (Wang et al., 2020). Furthermore, the presence of symptoms of psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and stress has increased (Cortés-Álvarez et al, 2020; González-Ramirez et al., 2020; Palomera et al., 2021; Pérez-Cano et al., 2020). If not treated in time, these emotional problems can become chronic and trigger serious emotional disorders (Vindegaard & Benros, 2020) or increase the risk of suicide (Wasserman et al, 2020).

The population that has been most affected are those who have suffered losses during this pandemic since the circumstances in which the loss occurs can limit the processing of individual grief (Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020). Notably, risk factors such as age (Weinstock et al., 2021), female gender, multiple losses, shorter time since death, and loss of a child, spouse, sibling, parent, or grandparent (Tang & Xiang, 2021; Treml et al., 2020), belonging to a family in which there has been economic damage due to the pandemic are associated with more significant emotional impact (Fegert et al., 2020). This can have a series of consequences for physical and mental health (Kokou-Kpolou et al., 2020), and trigger a disturbance in grief that is often associated with a reduction in the quality of life (Eisma & Tamminga, 2020). As reported by Treml et al. (2020), high levels of prolonged grief symptoms were significantly associated with less satisfaction with life (SWL).

SWL refers to a cognitive and global assessment of a person's quality of life (Diener et al., 1985; Meule & Voderholzer, 2020). That is, it is the perception that a person has of their own subjective well-being (Rajani et al., 2019). Indeed, SWL is a core element of subjective well-being, together with positive and negative affect (Diener et al., 2002). It is known that subjective well-being is influenced by variables such as health, socio-demographic variables, individual characteristics, behavioral variables, and life events (Garcia 2002). According to Diener (2000), subjective well-being has three characteristic elements: its subjective nature, which is based on the person's own experience; its global dimension, as it includes an assessment or judgment of all aspects of one’s life; and the necessary inclusion of positive measures, as its nature goes beyond the mere absence of negative factors. In this regard, several studies have shown the importance of examining life events in their impact on well-being (Kettlewell et al., 2020).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the relationship between SWL and some sociodemographic factors has been examined. According to a study by Rajani et al. (2019), being male, having economic difficulties, being unemployed, and being single was associated with lower levels of SWL. On the other hand, Passos et al. (2020) reported that greater SWL was associated with being female, having a higher educational level, being a student, and living with relatives or a partner in the period of social isolation. It is important to mention that the association between gender and SWL is not completely clear since it has also been reported that men show greater SWL during this period (González-Bernal et al., 2021). Additionally, it has been observed that being married and having a satisfactory income are associated with more SWL (El-Monshed et al., 2022).

Despite the relevance of well-being and SWL as protective factors against psychosocial risk phenomena, research is incipient in this field of study (Vélez, 2015). In Latin America, there is scarce literature on SWL. For example, some studies conducted in Mexico and Chile have reported the relationship between SWL and certain sociodemographic variables, such as gender, age, income, family, and health satisfaction (Gordon et al., 2018; Martell-Muñoz et al., 2016; Pérez & Maturana, 2012). Likewise, other studies in Spain have reported the relationship between SWL and age, income, education, level of physical activity, satisfaction with leisure activities, social contacts, and perception of health and illness (Carrión et al., 2000; Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2001).

To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet examined SWL among bereaved people in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the literature states, SWL is related to affective elements, such as the loss of family members after the pandemic. Therefore, this study aimed to explore sociodemographic variables associated with the perception of SWL in Mexican adults who lost a loved one during this period.

Method

The present cross-sectional study was part of a larger research/intervention project exploring multiple clinical factors of Mexican people who accessed a free online platform devised to provide emotional support for people experiencing grief during the COVID- 19 pandemic (Dominguez-Rodriguez et al., 2021), conducted between December 2020 and April 2021.

Participants

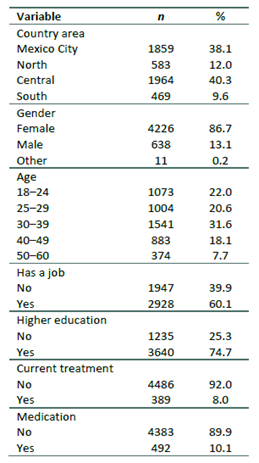

Using non-probability sampling, 4875 participants were included in this study. They had a mean age of 33.18 years (SD = 9.8). Most of them were employed females, with higher education. The majority of respondents had lost their relatives or loved ones between 0 and 3 months before data collection. The detailed information about the sample is presented in Table 1.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables. Participants were asked to report their gender, employment status, current treatments (psychological and pharmacological), and if they had had a suicide attempt in the last three months. In addition, their age in years, area of the country, educational level, and time since the loss was inquired. The area of the country was coded using four large geographical categories following an existing classification (Rivera-Rivera et al., 2020).

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). This instrument was designed by Diener et al. (1985). It consists of 5 items in which the participants indicate how much they agree with each question, with response options within a Likert format ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The scale ranges from 5 to 35, where the highest scores indicate greater SWL (Vázquez et al., 2013). This scale has been validated in Mexican population, obtaining good internal consistency results (α = .74; López-Ortega et al., 2016). In the present study, internal consistency reliability was even higher (α = .87).

Procedure

The study took place from December 2020 to April 2021, through a self-administered intervention platform, Duelo COVID (COVID Grief). Detailed information on the recruitment process has been addressed elsewhere (Domínguez-Rodríguez et al., 2021). The participants were recruited through social networks such as https://www.facebook.com/DueloCovid and articles on the news media. No email was sent to potential participants to invite them to participate in the study.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico (Approval ID: CEI-2020-2-226) and it is registered in Clinical Trials (NCT04638842). To receive the intervention, all participants had access to informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Only adults aged 18 or older were allowed to register, and their data (e.g., e-mail) was protected. No confidential data was required from participants such as their names, addresses or telephone numbers.

Data Analysis

First, the association between each study variable and SWL was examined, for which mean comparisons were conducted with a series of ANOVAs. Results with p < .05 were considered statistically significant. Those variables that obtained significant results were entered simultaneously in a multiple linear regression analysis. In addition to the p-value, 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the regression coefficients were also examined.

Assumptions of the regression model were checked through visual inspection and quantitative indicators. Evidence of potential heteroskedasticity was observed for age when conducting ANOVA; however, very similar results were obtained when a procedure that did not assume equal variance was implemented. Also, a slight deviance from normality was observed for residuals in the multiple regression analysis, but due to the large sample size this was considered of negligible importance. All the other assumptions were reasonably met for all models. The statistical software used was R version 4.0.3.

Results

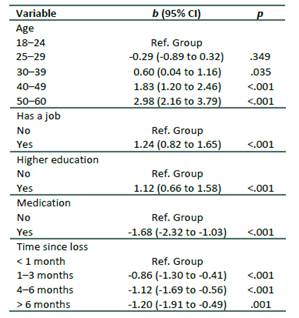

Due to the limited sample size of people who self-identified with “other” gender (i.e., neither female nor male; n = 11), they were excluded from the following analyses. Then, bivariate associations were examined with ANOVA. As presented in Table 2, age, job status, higher education, medication status and time since loss were significantly associated with SWL. Specifically, life satisfaction tends to increase with age. Also, participants who had a job or higher education had more life satisfaction than those that did not. On the other hand, individuals who were taking psychotropic medication had, on average, significantly lower SWL scores. Finally, it seemed that life satisfaction diminished as time passed since the loss.

Next, all the variables with significant associations with SWL were entered simultaneously into a multiple regression model. When this was done, all of them remained significant (Table 3). Age (especially ≥ 30), having a job and higher education were associated with more SWL. Meanwhile, taking psychiatric medication and having more time elapsed since the loss were associated with less SWL. Overall, the model comprising all predictors explained 4.2% of the variance of SWL.

Discussion

This study aimed to address the relationship between various sociodemographic variables (e.g., gender, age, educational level, marital status) and SWL in people who lost a family member or loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. We found that age, having a job, and higher education were positively related to SWL, whereas taking psychiatric medication and having more time elapsed since the loss was inversely associated with SWL.

Regarding the effect of age on SWL, Karataş et al. (2021) did not find a significant relationship between these two variables. In contrast, our study found that age was associated with more SWL, this is in line with Helliwell et al. (2020). This could be explained by the fact that, as the individual moves through life and experiences different adverse situations, they become more resilient, even to the death of a loved one.

Our results also showed that, on average, unemployed individuals had lower SWL. This is consistent with the literature, which repeatedly showed an association between unemployment and SWL (Chen & Hou, 2018; Rajani et al., 2019). Although recent job loss was not assessed in the present study, it is possible that a percentage of unemployed individuals had lost their jobs in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. As reported in previous studies, fluctuations in employment status tend to coincide with changes in SWL levels (Gander et al., 2021). Moreover, it has been observed that the decrease in SWL resulting from unemployment tends to be persistent even if the person manages to get another job (Hahn et al., 2015), and becomes greater the longer the time of unemployment (Richter et al., 2020). In the face of adverse life events such as the loss of a loved one, it is expected that unemployment will have an additional negative effect on SWL. In particular, it may exacerbate financial concerns and, at the same time, restrict the individual's ability to derive social gratifications from their work contribution. This result is consistent with the research of González et al. (2020), in which economic security, provided by having a job, was a determining factor in SWL.

Relatedly, an association was also found between higher education and SWL. This is consistent with previous studies (Dahiya & Rangnekar, 2020; Passos et al., 2020). There are some plausible explanations for this finding. First, as in the case of unemployment, it is possible that higher education is associated with higher socioeconomic status and this, in turn, is related to higher SWL. Second, it is worth remembering that SWL is a cognitive activity; since higher education is an indicator of cognitive reserve (Martino et al., 2021), it can be expected to be associated with greater capacity to evaluate one's own life as satisfactory. Finally, it is also possible that a higher educational level implies a greater capacity for cognitive flexibility, as indeed was found in a study conducted during COVID-19 (McCracken et al., 2021). This would suggest that people with higher education are better trained to accept their emotions without being trapped in a repetitive thought pattern and this, in turn, is reflected in greater satisfaction with their lives.

Our results also revealed that the use of psychiatric medication was associated with a lower level of SWL. The most parsimonious way to interpret this result is to consider medication as an indicator of the severity of psychopathology. Indeed, it has been solidly evidenced that poor mental health decreases SWL (Lombardo et al., 2018). For example, depression has a negative correlation with SWL, even after statistically controlling for a set of other variables (Sousa et al., 2019). Given this background, it logically follows that people whose suffering is so intense that they require medication, are those with lower levels of SWL. It should be mentioned, however, that in the present study no data were collected on the initiation of medication use. Therefore, it is not possible to determine whether its use began after the bereavement or whether it corresponds to a pre-existing condition.

An unexpected finding of our study was that longer time since loss was associated with greater impairment in SWL. This is in opposition to what was found by Bratt et al. (2017), who reported that longer time since loss was related to greater SWL. Likewise, already in the context of COVID-19, Tang et al. (2021) found that the longer the time since loss, the lower the levels of anxiety and depression. Our result contradicts these studies and eludes a simple explanation. It is possible that, as the data collection was conducted through a bereavement intervention platform, this may have led to self-selection bias. Specifically, it may be that these individuals constitute a specific subpopulation for whom suffering due to bereavement has increased over time, as opposed to the course it usually follows in the general population. However, this is only one of many possible interpretations and, due to the lack of further data, lies in the realm of speculation.

Thus, the results indicate that being older, employed and having a higher educational level are associated with higher satisfaction with life. This suggests that care and attention should be channeled to a greater extent in the population that does not have these protective factors. This implies major challenges for the Mexican context where the median age is 29 years, the majority is without higher education (only 21.6% of the population aged 15 years and over has higher education) and with high unemployment rates (5.2% in June 2021) (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, México, 2020-2021).

Regarding nonsignificant results, it was found that gender was not significantly associated with SWL. This is consistent with Karataş and Tagay (2021), who stated that gender does not significantly predict resilience, and with Helliwell et al. (2020), who found little difference in SWL between women and men measured before and during the pandemic. In contrast, Raza et al. (2020) found that women reported less SWL than men during the COVID-19 crisis. Our study, thus, adds yet another element to the existent mixed findings in the literature. Future studies may explore possible moderators that explain this inconsistency of results.

Limitations and Strengths

The main limitation of the study is that the data were obtained from participants who sought self-applied treatment to cope with the loss of a loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic, which could bias their responses aimed at obtaining the intervention. Another limitation to consider is the limited representativeness of the evaluated sample, which prevents the generalization of the results to the entire population. Furthermore, several variables that have been found to be predictors of life satisfaction were not included in our database. Future studies could include variables such as socioeconomic status, mental health status prior to the loss, relationship with the deceased, resilience, subjective happiness and hope to prevent fear of the consequences of COVID-19.

The sample size is highlighted as one of the strengths of the study. The results of 4875 participants were reported, which exceeds the sample sizes typically reported in previous studies. Likewise, the study participants were people from different parts of the country who had lost a loved one during the pandemic. Even though this was not a probabilistic sample, they constitute a group of special interest due to their particular characteristics.

Conclusion

In this study, age, being employed, and having higher education were predictors of better SWL. On the other hand, taking psychiatric medication and having more time elapsed since the loss were associated with worse SWL. Our results support the need to join efforts in mental health services to promote the well-being of the population, especially in those who may be at greater risk (such as bereaved persons).