Introduction

Personality refers to idiosyncratic, consistent and stable tendencies. Traditionally, the trait model has predominated in the study of personality. This model conceptualizes personality under the label of traits, which are internal variables that have a causal role in the behavior. Psychologists working whithin this model have described the structure of the personality according to a set of factors (e.g., Big Five; Norman, 1963).

On the other hand, from a behavioral approach, personality is a consistent and stable behavioral trend that does not explain nor cause behavior. Rather, it is the individual’s behavior itself in a specific context (Santacreu et al., 2006). The interbehavioral theory formulated by Kantor (1924) provides the basis for studying personality in observable and objective terms. From the interbehavioral theory, what is studied is the interaction between an individual and a specific context, as well as the variables that influence that interaction. Personality reflects the synthesis of learning experiences that the person has accumulated throughout his or her life. Personality is a dispositional variable that does not directly take part in the interaction, but influences it. Ribes (1990, 2018) was one of the contemporary authors who applied the interbehavioral theory to the study of personality conceptualized as an “interactive style”.

In this work, we adopt a behavioral approach to measure personality. Establishing as a starting point that personality is a dispositional variable that reflects the synthesis of the experiences an individual has accumulated throughout his or her life, we can assess personality in two ways:

Obtaining information about the verbal synthesis that people make of their behavior (what people say about themselves).

Obtaining information about the behavior that people show in a particular situation (what people do or choose to do in a specific situation).

In the first case, we assess personality through self-reports. In the second case, we employ objective tests. Self-reports and objective tests could be complementary methods for assessing personality. Self-reports are widely known, and their use in personality psychology is widespread. However, the same does not apply to objective tests.

The aim of this work is to introduce objective tests as a useful tool for personality assessment. To this end, we will describe objective tests and the steps required to design them. In addition, we provide supplementary material that reflects the application of these steps to the design of a fictitious self-control objective test.

What is an objective test?

Objective tests are instruments to assess people’s behavior in order to infer a psychological variable (Anastasi, 1954; Cattell, 1957; Scheier, 1958). These instruments have been widely used to measure variables such as spatial ability, verbal comprehension capacity or processing speed. In personality, the most employed instruments have been self-reports. However, the pioneering work of Cattell and Warburton (1967) showed that objective tests could also be designed to measure personality variables.

Self-reports present questions or descriptions to which the assessed must respond, generally with a scale of agreement. These instruments require people to evaluate and describe their own behavior. Contrary to self-reports, objective tests are not based on verbal descriptions. Objective tests are based on the sequence of observable behaviors of the people being assessed (Anastasi, 1954; Cattell, 1957, 1958; Ortner & Proyer, 2015; Scheier, 1958). According to Cattell's terminology (e.g., Cattell, 1958), objective tests allow us to obtain T-data (test-data: observable behaviors that people show in specific situations), meanwhile self-reports allow us to obtain Q-data (questionnaire-data: verbal descriptions of the behavior).

The objectivity of an instrument can be studied from two points of view. On the one hand, we can consider the point of view of the researchers that carry on the assessment. On the other hand, we can consider the point of view of the people who are being assessed. Self-reports and objective tests are objective from the point of view of the researchers that perform the assessment, since the scores they obtain do not require a subjective interpretation (the assessors do not have to interpret the results but assign scores according to previously established criteria). Different researchers will obtain the same score. However, this is not the case if we consider the point of view of the person being assessed. As self-reports are based on verbal descriptions, when people complete them, a degree of subjectivity is sometimes inevitable. Instead, as objective tests record the sequence of responses that people show when they face a situation, the subjectivity is easily avoided. Therefore, objective tests present a double objectivity. Neither the responses of those evaluated nor the scores obtained by the researchers are affected by subjectivity (Cattell & Warburton, 1967; Ortner & Proyer, 2015).

The first objective tests designed by Cattell and Warburton (1967) had a mechanical or pencil and paper format. These tests have been called first generation objective tests (Ortner & Proyer, 2015). Later, thanks to computer advances, objective tests began to be developed in a computerized format. These are called second generation objective tests.

The following are some examples of second generation objective tests:

Betting Dice test (Rubio & Santacreu, 1998): This test measures risk tendency. It presents two dice rolling in the screen. Participants have to make a bet about the result of adding both dice, choosing between four options: a result greater than 4, greater than 7, greater than 9 or equal to 12. The probability of obtaining the first option is greater than the second option and so on (although the expected value is identical for the four options). The lower the probability of obtaining the result, the riskier the bet.

Balloon Analogue Risk Test (Lejuez et al., 2002): This test also measures risk tendency. The screen presents a balloon that has to be inflated. When participants inflate the balloon, they receive coins. They can choose when to stop inflating the balloon and therefore, when to collect the coins. If they inflate the balloon too much, it explodes and they do not receive the accumulated coins.

Conscientiousness test (Hernández et al., 2003): This test presents a set of different types of figures organized in rows and columns. The figures represent different types of trees. A model tree is shown to the participants, and they are asked to select all the figures that are similar to the model. The test records the pattern of scores, obtaining a measure of conscientiousness.

Multidimensional Objective Interest Battery (Proyer, 2006). This battery includes an objective test to assess vocational interests. For example, in one of the subtests, participants are asked to distribute 100,000 euros to a set of associations. The amount of money allocated to each association is considered a measure of interest.

Mastery Performance-Goal Orientation Test (Romero et al., 2020): This test assesses goal orientation: mastery- and performance-orientation. It presents a matrix with different figures that belong to different categories. By clicking on the figures, the participants get points. One of the categories offers a higher number of points (optimal figures). Participants can obtain a high number of points either by learning which category is optimal or by clicking on a large number of different figures. People who try to get points by restricting the clicks to the optimal category are classified as mastery-oriented. People who click on a large number of figures without discriminating between categories are classified as performance-oriented.

Despite the potential usefulness of objective tests, they have hardly been used in personality literature. This underutilization can be attributed to inherent limitations and findings from previous research that compare them with the results of self-reports (see Dang et al., 2020 for a review).

On the one hand, a main reason that may have contributed to the lack of widespread use of objective tests is that their design involves more costs than the design of self-reports, which is a significant limitation. As we will elaborate later, the development process is intricate and involves defining the construct, designing a mechanical or computerized way of recording observable data, conducting pilot testing, readjusting the design, etc., to ensure reliability and validity. These steps are not only time-consuming but also incur substantial costs, which can be a barrier to the development of new objective tests.

Moreover, second-generation objective tests typically require computerized administration, necessitating collaboration with computer technicians for programming. Although technological advancements have made the design of these tests more feasible, they still demand ongoing maintenance and updates to remain functional and relevant amid rapidly evolving digital platforms. Hence, forming a multidisciplinary team is essential and beneficial.

In addition, and related to the above, the practical administration of objective tests requires equipment with specific technical requirements, which contrasts with the ease of administering paper-and-pencil questionnaires. This need can limit the accessibility and applicability of objective tests in various contexts.

On the other hand, an objective test often focuses narrowly on a specific personality variable, and to capture other interacting personality dimensions, it is necessary to use different objective tests. This contrasts with the ease of using a questionnaire, which can measure different personality variables through a single instrument and is potentially less time-consuming.

Finally, we believe that one of the key reasons contributing to the underuse of objective tests is that, in the research conducted by Cattell, T-data did not correlate with Q-data (e.g., Ortner & Proyer, 2015; Smith, 1988). Cattell and his team aimed to employ multiple methods to assess the same variable. The lack of correlation between self-reports and objective tests generated inconsistencies regarding their theory, which motivated personality-trait researchers to employ self-reports to the detriment of objective tests. However, the lack of correlation between T and Q data is a fact that should be expected. What we say and what we do does not necessarily coincide. For example, someone can say that he or she is conscientious. However, when observing their behavior, we may see that their desk is messy or that they solve crossword puzzles in a non-systematic way. This person may not have intended to lie. Rather, the subjectivity of language contributes to the lack of correspondence between what we say and what we do. In addition, social desirability or acquiescence are biases that can influence people to distort their descriptions of themselves. Although the results obtained by Cattell's team seem to have generated a lack of confidence in the objective tests, it is important to note that the absence of correlation between what we say and what we do does not mean that objective tests or self-reports are not valid. Objective tests and self-reports measure different aspects of the same variable (Ortner & Proyer, 2015).

We believe it is possible to take up Cattell's proposal again. The contributions of this author and his collaborators, as well as the personality behavioral approach, will provide psychologists with the basis to design objective tests to measure personality. Research can benefit from employing objective tests, as they provide complementary data to those used by other instruments. The design of these instruments requires interdisciplinary work, but this is enriching and can advance psychological science.

In the following sections, we will describe the aspects that we consider sufficient and necessary for a psychologist to start designing an objective personality test.

Designing an objective test

General requirements

Before describing step by step how to design an objective test, it is important to know the general requirements in order to assess personality through this type of instrument. Let us begin by briefly describing the behavioral theory of personality that will be the basis of the objective test design. We will integrate the contributions of Cattell but, unlike his group and the vast majority of psychologists attempted, we will not identify personality traits, we will identify behavioral patterns or interactive styles (Santacreu et al., 2002).

Behavioral theory has an obvious interest in observable behavior and aims to explain behavior based on context contingencies. However, recently, this theory has also been interested in the role of people's history, synthesized throughout the life of the individual. The following is a summary of the fundamentals that allow us to study personality.

Functional relationships between individual’s behavior and specific context events explain the change of the behavior in that context. In other words, in a particular moment and situation, individual behavior (B) is a function (f) of the context contingencies (C). People are different because of genetic, epigenetic, or ontogenetic experiences. We postulate that individuals constantly synthesize their experiences and learnings in order to act (respond or decide) as quickly as possible (as mentioned before, the synthesis of their history is expressed both as behavioral trends and as verbally expressed rules of behavior). When we study the differences in the behavior between individuals, we consider that the behavior (B) is a function of the characteristics of the context contingencies (C), but depends on the dispositional factors of the individual (I).

B= f (I, C)

Cattell and his group identified three different areas that allow classifying a person's history: abilities, personality, and motivation (e.g., Cattell et al., 1972). Substituting the individual (I) for each of his areas, the following formula reflects that the behavior (B) is a function (f) of the mentioned categories of the individual [Motivation (M), Abilities (A) and Personality (P)], and the contingencies of the context (C).

B = f [(M, A, P), C]

To study the role of the characteristics of the individual in the explanation of behavior, according to the previously described formula, it is essential that the contingencies of a specific context remain stable. Furthermore, the context must not influence the participant’s behavior. In this way, only the characteristics of each person will influence behavior. Therefore, the test that will measure the variables of each individual has to present an identical context for all the participants and must not report the result or consequences of the behavior that we aim to measure.

B = f (M, A, P)

In the same way, to study individual´s personality, motivation and skills must not be influencing the behavior that we are going to measure. This means that, first, in order to study personality through a test; all participants should show motivation to complete it. If they are not motivated (if they do not perform any response), we will not be able to measure the variable of interest. Secondly, the individual must have the necessary skills to complete the test (for example, he or she should know how to use the mouse in a computerized test). Otherwise, ability will contaminate the results. If the behaviors of people who complete the test are not differently influenced by motivation or abilities, then we could measure the personality through these behaviors.

B = f (P)

We should remember that, in all cases, when administering an objective personality test we will be measuring the observable behavior while the individual is facing (doing, choosing or solving) a task in a specific context.

Applying all of the above, the standards that an objective test must meet in order to measure a personality variable are the followings:

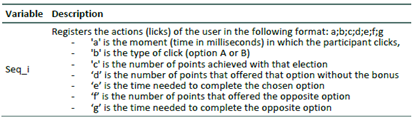

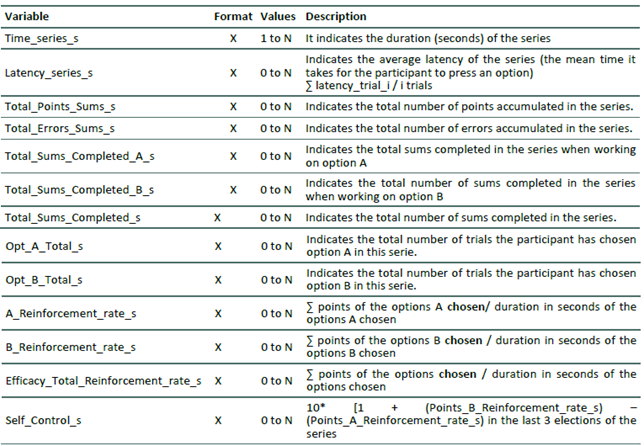

The test should allow us to measure personality based on observable responses. It will be necessary to determine which data the test should record in order to infer the personality variable. Generally, objective tests record data such as the sequence of responses, the frequency, latency, the duration of a response, etc. (Cattell & Warburton, 1967; Ribes, 2018; Santacreu et al., 2002; Scheier, 1958).

The test instructions should be clear, simple and concise. They should not allow participants to guess which variable the test measures, that is, the variable should be masked. If so, it will be more difficult for participants to distort their answers in a certain direction (Cattell & Warburton, 1967; Santacreu et al., 2002, 2006).

Related to the above, the test should not offer feedback on the personality variable being measured (Ribes, 2018; Santacreu et al., 2002, 2006).

The task has to be simple enough so that the competencies do not influence the execution of the participants (Cattell & Warburton, 1967; Santacreu et al., 2002). If a competence is needed to perform the test (e.g., spatial orientation), we could only assess personality on the participants that are competent in it.

The test should show adequate psychometric properties referred to observable variables: reliability and validity.

The following requirements should be verified after employing objective personality tests to assess personality of an individual.

Participants must have shown a minimum level of motivation when facing the task proposed. We should establish a motivation criterion that determines the minimum number of responses that a participant must show so that we can assess his or her personality (Santacreu et al., 2002).

Participants must have shown an undoubted level of competence when performing the task. In some tests, we should establish a competence criterion. If a participant does not meet the criterion, we could not assess his or her personality (Santacreu et al., 2002).

Participants must have shown consistency throughout the trials of the test (note that here we refer to individual’s consistency, not to the consistency of the group data). The assumption of individual´s consistency has generated an intense debate in personality psychology (see Hernández et al., 2006). If people do not show consistency, we cannot make predictions about their behavior. Therefore, it will be important to check the degree of consistency they show in the test.

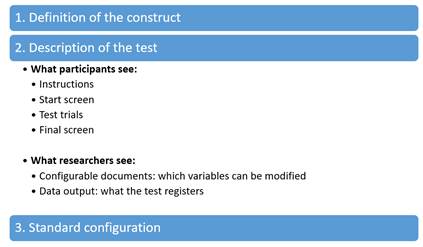

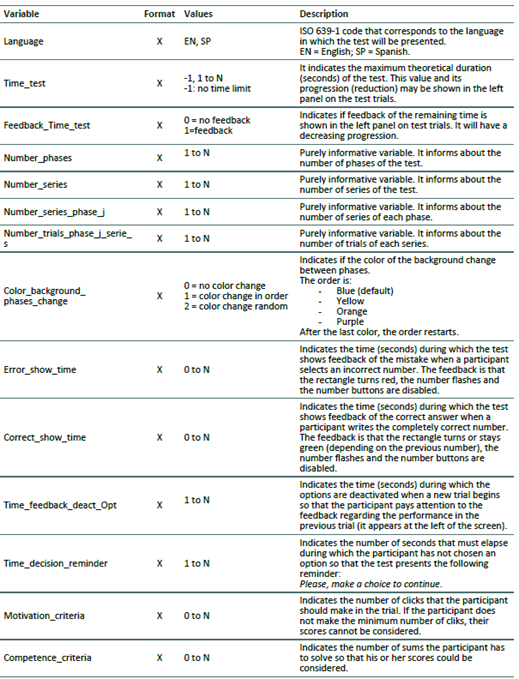

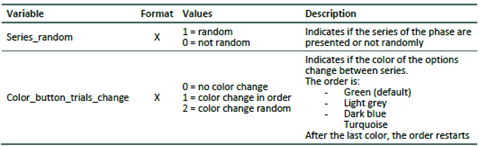

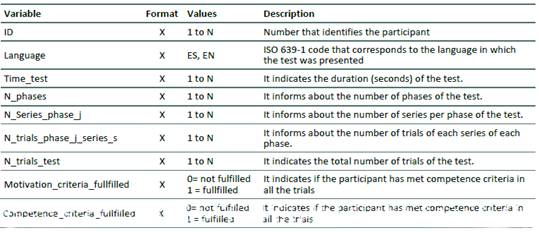

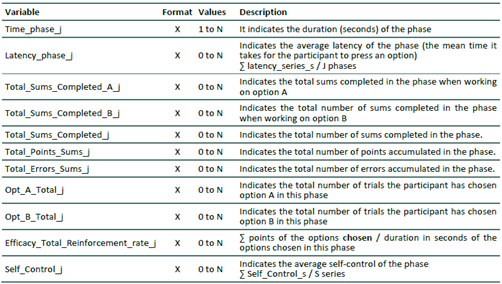

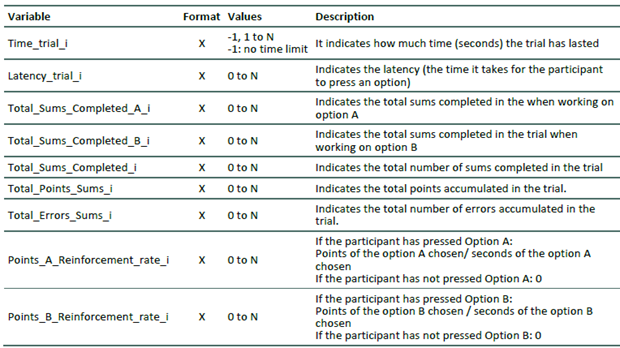

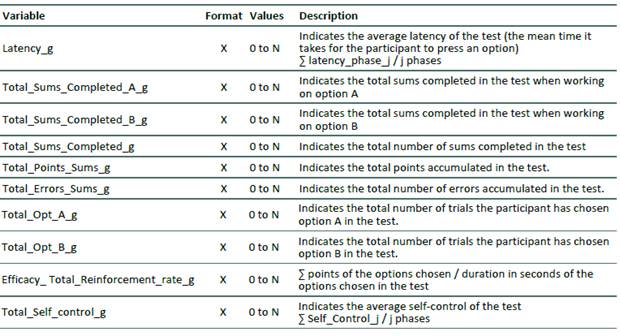

Once we have described the general requirements, we will move on to explain the specific steps needed to design an objective test. In order to design an objective test, it is necessary to prepare a test description document. This document has different parts. First, it should describe the variable that we are going to measure. Secondly, it has to describe the test as it is presented to the participants. Third, it has to describe the variables that the researcher configures before administering the test (in order to change their parameters if necessary) and the variables that the researcher obtains after administering the test. This document should be prepared to be comprehensible not only to psychologists but also to the computer technicians responsible for programming the test. As mentioned, a multidisciplinary team will be both essential and beneficial. Fig. 1 summarizes the sections that this document should have. In the supplementary material (Appendix 1), readers can find an example of a fictitious self-control test.

Steps for designing an objective test

1. Choose and understand the personality variable

First, we need to choose and understand the personality variable that is going to be measured. It is necessary to carry out a literature research on the construct to know how the most important theories that have studied it, how it is defined, in what context it is important and how it has been measured. The test description document should start with a summary of this information taking into account, first of all, the basic research on the personality variable that we intend to measure. If we do not do so, it will be impossible to design a test to measure it.

2. Think beforehand how the variable could be recorded behaviorally

The variable should be measured based on observable responses, a task that presents considerable challenges. At this early stage, it is essential to develop a general idea about how the variable could be behaviorally measured. This involves brainstorming and identifying a range of behaviors or responses that accurately reflect the underlying construct we aim to assess. Later on, and once we have thought about the morphology and functionality of the test, it will be when we will decide which specific variables our test will record. For example, to measure risk tendency, we must consider whether the participant chooses risky options, but depending on the morphology of the test, the variables to be recorded can vary. The Balloon Analogue Risk Test (Lejuez et al., 2002) records how many times the participant presses the pump to inflate a balloon. The more the participant presses, the higher his or her risk-tendency. The Betting Dice test (Rubio & Santacreu, 1998) registers in which of the four options presented in each trial the participants click. The test assigns 1 point to the 1st option (the lower risky bet), 2 points to the 2nd, option and so on. The mean score of the test trials is the score of each participant. The higher score, the higher the risk-tendency of the participant. Both tests measure risk tendency in observable terms, but the specific variables they record are slightly different. As mentioned before, objective tests usually record the latency, frequency and/or the duration of the response, the correct responses and the errors, the sequence executed, etc.

3. Design the test morphology and functionality

This step requires researchers to be creative and thoughtful about how the test should operate to measure the variable of interest effectively. In designing the test morphology and functionality, it is necessary to consider how the test will function in practice, ensuring that the measurement of the variable is accurate and reliable. In addition, to measure personality, the variable should be masked, that is, the participants should not be able to easily guess which variable is being measured.

Some objective tests are designed as a game or a competitive task, which helps to motivate participants to take it. For example, the Balloon Analogue Risk Test (Lejuez et al., 2002) can be presented to the participants as a game in which the balloon has to be inflated to obtain coins. Sometimes it will be difficult to present the test as a playful task, but if we present it with an attractive graphic design, we can also favor the motivation of the participants to complete it.

As we have announced, this step is likely one of the most challenging and may take considerable time-potentially weeks or even months-to complete. We recommend that researchers review already published objective tests to have a reference for how to obtain observable recordings of variables. Additionally, it may be useful to review and analyze existing games or video games available. Sometimes, even if they were not designed for this purpose, some existing games contain a basis for measuring certain psychological variables. For instance, regarding risk tendency, researchers might ask themselves, considering the definition of the variable, is there any board game that can measure this variable? What modifications could be made to measure risk tendency? It can also be useful to think about everyday activities or sports, as they can sometimes serve as a basis for measuring variables. Continuing with the example of risk tendency, a person who practices climbing might ask how they could design a situation to measure risk tendency in that context. We also recommend that researchers brainstorm various designs and discuss them with their colleagues. Collaboration and the exchange of ideas with other professionals can foster creativity and lead to innovative solutions.

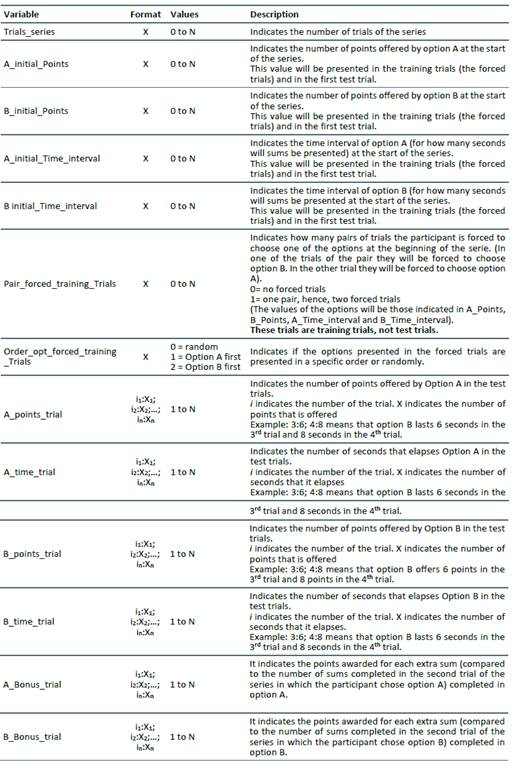

It will be necessary to determine how the task will work (for example, will there be a time limit? If so, what will happen if the participant does not respond before the time limit?). We will also have to consider whether the test will have different phases and series. A phase is a group of trials with similar characteristics. For example, in a persistence test, there may be a first learning phase of, for example, 12 trials and a second extinction phase of, for example, 10 trials. We may assess persistence as the number of responses in the extinction phase (second phase). The trials of a specific phase that share one or more characteristics can also be grouped as a series.

In a parallel way, we will have to think about what the participant will see and what the researcher will see and describe it in the test description document. In the following, we describe what needs to be included when describing these sections (see also Appendix 1 for an example).

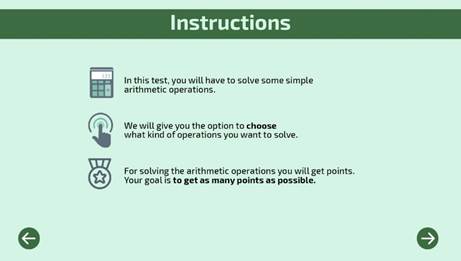

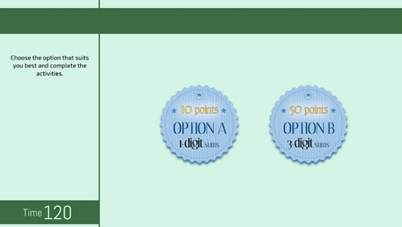

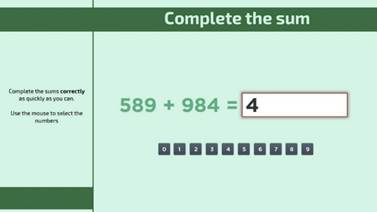

What participants see: instructions, test trials and final screen

When the participants complete an objective test, they will have to read the instructions that indicate how the task works. Later, they will face the test trials. Finally, they will see a screen that indicates the end of the test. We will describe these parts in detail:

Instructions. The instructions should describe clear and briefly the purpose of the task. Researchers can also include in this section images or a video that shows how the task works.

Instructions should not reveal which variable is being assessed, and they should not clearly direct the behavior. It is important that the participants execute the responses in a natural way.

In the test description document, we should describe how many screens are needed to show the instructions, how are these screens and the text (or visual sources) that will be presented.

The instructions will be configurable by the researcher (see section “What the researchers see: configurable variables and data output” below).

Test trials. In these trials, the participant will perform the test. Again, the researchers will be able to configure the number of trials, the text and the feedback (see section “What the researchers see: configurable variables and data output” below). Sometimes, it will be adequate to configure initial trials (usually called training trials), so that participants become familiar with the task.

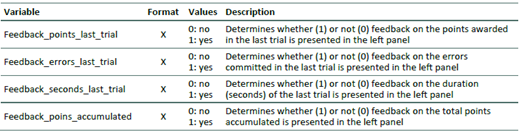

As mentioned before, the test should not offer feedback on the variable that it assesses. The test can provide feedback on aspects other than the main variable. In addition, in some tests it will be appropriate to offer feedback on the remaining time to maintain participant motivation high.

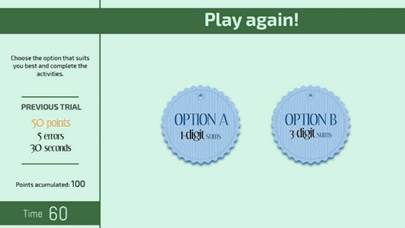

Final screen. Participants must know that the test has been completed. Therefore, in the test description document it will be necessary to indicate how this final screen looks like. Generally, it is a screen with a simple message ("The test has finished") and a button under the text indicating "Exit".

What researchers see: configurable variables and data output

The researchers will have access to files of the computer program where they can configure the instruction screens and the variables of the test. In addition, they will have access to files with the data output.

When designing the objective test, we have to make it clear in the test description document which elements the researchers will be able to configure. In addition, when designing the test, we should indicate in the test description document which variables will be visible in the data output once the researchers have administered the test to a participant.

Data output: The objective test must provide data per trial, per series, per phase and overall test data (generally, total scores and means). The data will only be available to the researchers.

First, the data output should show if the participant has fulfilled motivation and competence criteria. The motivation criterion usually requires a minimum number of responses. The competence criterion usually requires a minimum number of hits or a maximum number of errors. If the participants do not fulfill the competence criteria, participants cannot be assessed by the test.

Only if the participant has fulfilled motivation and competence criteria, we can assess their personality.

4. Design standard instructions and a standard configuration

Up to this point, we will have already designed the morphology and functionality of the test and will have considered which variables the experimenter should configure. At this stage, we will have to design the standard instructions and a standard configuration that we consider adequate to measure the variable of interest. This will be the base configuration for future pilot studies and may be adjusted if required. The standard instructions and the standard configuration should be included in the test description document.

5. Conduct pilot tests and make adjustments

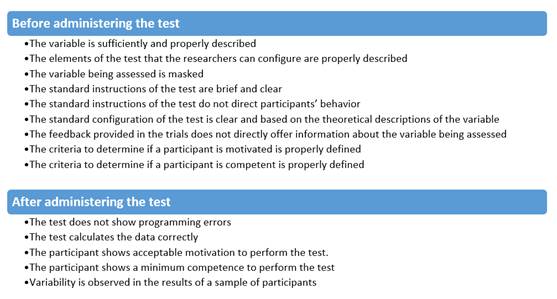

Once we have a preliminary version of the test and a standard configuration programmed, it will be necessary to carry out pilot studies with samples of 10 or 20 participants. We must check that the software program runs without errors and that the data output is correctly registered. In addition, we should check if the participants fulfill the motivation and competence criteria to assess the variable of interest.

Fig. 2 summarizes what we need to check in pilot studies. These studies will allow us to adjust the instructions and the configuration of the test in order to run a version of the test that allows us to measure the personality variable adequately. On some occasions, the participants do not properly understand the instructions that we design in the first moment, so it will be necessary to change them. In addition, sometimes the configuration that we consider as a starting point is not proper. For example, we may consider a specific time limit but, when administering the test, we could see that it is insufficient for the participants to complete the test adequately.

6. Study the psychometric properties of the final version

Once we have constructed the final version of the test, we should administer it to larger samples to study its psychometric properties. The test should show reliability and validity (see, for example, DeVellis, 2016). We should demonstrate that the final version of the test allows us to measure the variable as described in the theoretical approaches (see Cronbach & Meehl; 1955). To obtain evidence of validity, we should administer our test together with another test in which the task presents a different morphology but a similar functionality (that is, that measures the same variable but presents a different-looking task). We should also study construct validity by studying whether the test shows a significant relation with variables with which, according to the theory, it should be associated. It is important to emphasize again that the relation between the test score and the behavior observed in real situations cannot be high. In real situations, the behavior of the individual depends on their skills, motivation and personality, but also on the contingencies of the situation. On the contrary, in a test, the task provides no feedback of execution, and the behavior is not therefore a function of the contingencies of the task.

7. pdate the test when necessary

Although we have produced a final version of the test, this does not mean that it is invariable. Advances in theory may mean that it is necessary to review whether the test continues to fit the theoretical approaches. In addition, in some cases it may be appropriate to try out different configurations of the test to determine which of them allows us to obtain a better measurement of the variable.

On the other hand, we should not lose sight of the possible updates required from the technological point of view. Technology can advance rapidly, and this may mean that tests need to be updated so that it can be administered in the most recent browsers and computers.

Conclusions

In this work, we have presented what we consider fundamental to design an objective personality test. We have taken up Cattell's contribution, but establishing the behavioral theory of personality as a starting point.

To design an objective test is necessary to understand the variable we want to measure and to think in detail about how to measure it in observable terms. At this point, the experimental contributions of basic psychology are fundamental. Ultimately, the variable will be measured from the data obtained by a computer, which means that we have to apply our psychological knowledge to numerical variables that are more characteristic of computer science.

Designing an objective test takes time and effort, presenting a significant challenge. However, the effort is worth it. The level of precision achieved by using this type of instrument is enormous (objective tests allow to measure several responses, the time in which each one is made, its duration, etc.). In the research field, the use of objective tests will allow us to expand the conceptual analysis of personality variables. In the research but also in the applied field, objective tests will provide us with information free of subjectivity and bias. It is necessary to assemble a multidisciplinary team for this endeavor, but this approach is enriching and beneficial, as it brings diverse perspectives and expertise that can lead to more robust and innovative solutions.

We believe that, if objective tests to measure personality are implemented in the scientific community (as has happened with competency tests) the scientific study of personality might lead to a paradigm shift in Psychology. Researchers who study the behavior of organisms in extremely controlled situations will have to accept the importance of the ontogenetic history of individuals, especially humans. People are entities with a great capacity for learning. Like all living beings, humans grow and transform as individuals, accumulating what they have learned and synthesizing it in such a way that they can respond quickly if necessary in any context. It mobilizes their systems, organs, tissues and cells as a whole, to respond quickly (although not always successfully) to change in the context in which they live. Therefore, it is important to propose a model that explains how the individuals manage to reorganize what they are learning, and how they use their learnings to act effectively at another time.

It is at this point that the objective and accurate measurement of skills, motives, personality, competencies and knowledge is radically important. Without precision in the measurements, we cannot imagine models of the functioning of people in their relation with the context in which they live. Currently, we can only observe with some precision the changes that occur in an individual in a specific context, in the short term.

In our not so humble opinion, accurate and reliable measurements can aid progress in understanding human behavior. We hope that the rationale provided in this article will serve other researchers interested in designing objective tests to assess personality variables, which would make an important theoretical and methodological contribution to the literature.