Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has increasingly become a significant public health problem and economic burden for health systems worldwide. The global median prevalence of CKD is estimated at 9.5% [1], similar to the global prevalence of diabetes at 9.3% [2], which is considered the most common cause of CKD. This high prevalence of CKD has been attributed to a combination of individual factors such as aging, unhealthy lifestyle, and increasing prevalence of other comorbidities including obesity and hypertension. In addition, in low-resource settings, social determinants of health (SDOH) can also contribute to the high burden of the disease [3,4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines SDOH as the non-medical conditions influencing the environments where people are born, grow, work, live and age, all of which impact health outcomes [5]. SDOH also includes the wider set of forces that shape a person's daily life (economic policies, social policies and political systems) [5] and have been grouped into five domains that include economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context [6]. Notably, poverty is considered one of the most significant social conditions of our time [7], as it can hinder healthy behaviors and health care access, increasing the risk of exposure to environmental toxins such as lead, cadmium, and arsenic. Moreover, in vulnerable populations, CKD screening campaigns have shown a high burden of kidney disease that usually remains undiagnosed and untreated. Therefore, management of the individual-level (proximal) CKD-related factors alone would not be sufficient to reduce the burden of CKD, particularly in low-resource settings. There is extensive evidence demonstrating that it is necessary to integrate social (distal) factors into CKD management [8].

Current CKD management programs in low-resource settings are mostly based on targeting individual-level factors such as blood pressure, glucose, lipids, acidosis, anemia and albuminuria, using the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)-CKD clinical practice guidelines, as they are implemented worldwide [3]. While recent proposals suggest modifying this classification to incorporate kidney aging [9], it still remains centered on individual factors, lacking a broader social perspective [10].

Social vulnerability

Vulnerability is defined as [11]:

The probability that a subject exposed to a natural, technological, anthropic or socio-natural threat will suffer damage and losses, both human and material, at the time of impact of the phenomenon, also having difficulty in recovering from it, in the short, medium or long term.

From a social perspective, vulnerability refers to a household's state, inversely related to its ability to influence the forces that shape its destiny or mitigate their effects on well-being [12]. Social vulnerability can be explored by evaluation of the following five dimensions (D) proposed by Jimenez-Garcia et al. [12]:

D1, Household composition and basic social rights: This dimension evaluates household circumstances that may deplete essential resources (e.g., economic, educational, temporal, experiential) necessary to prepare, face and resist adversity. Some examples include households led by a single female head (single-parent household), low schooling, unemployment, and/or with children outside the school system.

D2, Income and access to consumer goods: This dimension, which probably has the greatest weight in the explanatory models of vulnerability (the lower the income, the greater the vulnerability), measures the total household income and classifies it according to the per capita income of the study area. Vulnerability is identified when a household has no income or when four or more individuals rely on a single income. It also considers access to basic goods and utilities, health services, and telecommunications, as being able to communicate is essential for managing emergencies.

D3, Quality and ownership of housing (unstable housing): The nature of the home, the property, and its location (generally in risk areas) can be sources of social vulnerability. Likewise, overcrowding increases vulnerability since it increases the number of potential victims in a single event and fosters conditions that may lead to traumatic stress.

D4, Segregation: Segregation implies vulnerability since socio-spatial exclusion decimates the effect of relief and protection mechanisms and dilutes the capacity of individuals to face adversities beyond their control. The remoteness of the home from care centers further heightens vulnerability.

D5, Immigration: Migrants, as minorities in urban areas, often face discrimination when seeking health care. Furthermore, internal immigration tends to cluster in the most marginalized and segregated urban areas, where access to basic services is limited, increasing vulnerability. As an example, Burgos-Calderón et al. describe how ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities, such as indigenous, Afro-Latin and Afro-Caribbean communities, due to their low socioeconomic status, language barriers, lower education attainment, lack of access to healthy nutrition, contaminated environments (all distal factors), have increased risk of early onset hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and CKD [8]. Moreover, in women of childbearing age, poor nutrition is recognized as a risk factor for low birth weight and kidney development problems [8,13].

Using exploratory factor analysis, Jiménez-García et al. identified eight factors as the most influential within the social vulnerability dimensions: young head of household (EDJH1), home with school dropouts (OUTSCHO), low-income household (VULNE), home without assets (BAGOOD), home without technologies (TIGOOD), unstable housing (HACIN), housing-overcrowding in segregated sector (SEGRE), and home with migrants (MIGRA). Each of these eight social vulnerability variables is assigned a binary value of 1 or 0 (where 1 represents the presence of a deficiency and 0 the absence of it). These data are incorporated into a social vulnerability index (SOVI) score, with a minimum value of zero (0, no deficiencies are seen), and a maximum value of eight, which is calculated as follows:

SOVI = ∑EDJH1 + OUTSCHO + VULNE + BAGOOD + TIGOOD + HACIN + SEGRE + MIGRA

Based on the SOVI formula, the authors developed a simplified version that categorizes households into three categories of varying degrees of social vulnerability: low (SV1), medium (SV2), and high (SV3). Households with 0 to 1 deficiencies are classified as having low social vulnerability (SV1), those with 2 deficiencies as medium vulnerability (SV2), and those with 3 or more deficiencies as high vulnerability (SV3) [12].

Conclusions

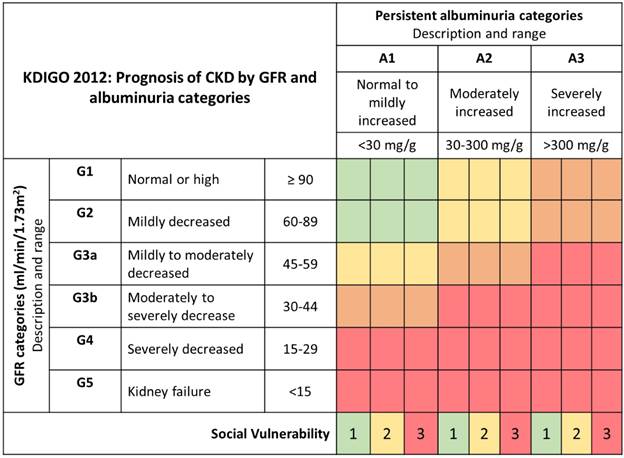

Given the current contrast between the importance of distal factors in the incidence and progression of CKD and their frequent neglect, we believe that it is crucial to increase the recognition of social vulnerability by incorporating it into the CKD classification, particularly in resource-poor settings. For this purpose, the simplified version of SOVI could be incorporated into the current KDIGO-CKD classification, particularly in the evaluation of patients living in low- income countries. Therefore, we propose to add a social vulnerability indicator to the KDIGO classification as shown in Figure 1.

Note. Proposal to add a social vulnerability measure to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) classification. CKD: chronic kidney disease; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; Green: low risk; yellow: moderately high risk; red: very high risk.

Source: The authors.

Figure 1 KDIGO 2012: Prognosis of CKD by GFR and albuminuria categories

Alternatively, other validated social vulnerability measures could be incorporated into the KDIGO-CKD classification instead, depending on the geographic location. For instance the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), which uses 16 U.S. census variables to help local officials identify communities that may need support before, during, or after disasters [14].

This perspective is in line with the concept of population health, which brings together individual or proximal factors (e.g., genetics, lifestyle, comorbidities) and social or distal factors (e.g., social, environmental, economic) in order to provide a more comprehensive approach to the problem of CKD burden, with the goal of promoting kidney health an improving current kidney prevention programs.