Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Biomédica

Print version ISSN 0120-4157On-line version ISSN 2590-7379

Biomédica vol.26 suppl.1 Bogotá Oct. 2006

Effect of blood source on the survival and fecundity of the sandfly Lutzomyia ovallesi Ortiz (Diptera: Psychodidae), vector of Leishmania

Pedro Noguera, Maritza Rondón, Elsa Nieves

Laboratorio de Parasitología Experimental (LAPEX), Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida, Estado Mérida, Venezuela.

Recibido: 26/05/05; aceptado: 13/10/05

Introduction.

The reproductive potential of sandflies depends on various factors, one of which is the type of host available as blood source, which is important in determining their capacity to serve as vectors.Objective. The present study evaluated the effect of the animal blood source on various biological parameters of Lutzomyia ovallesi (Ortiz) under laboratory conditions.

Materials and methods. Two-day-old females from a L. ovallesi colony were artificially fed to repletion using a chicken skin membrane with blood from seven different species of vertebrate hosts, horse, dog, cow, chicken, goat, pig and human. Life-span, time of oviposition, time for blood digestion, number of eggs laid, number of eggs retained and the total number of eggs were recorded.

Results. The results show the influence of blood source on different biological parameters of L. ovallesi. The results showed that in L. ovallesi, chicken blood is the most quickly digested (3.34 days) and gives the longest time of oviposition (5.88 days), the greatest number of eggs retained (10.20 eggs per female) and the greatest fecundity (30.80 eggs per female) compared with the other sources of blood studied. The most satisfactory animal blood source was chicken followed, in descending order, by goat, cow, pig, human, dog and horse.

Conclusions. The data showed that, in bio-ecological terms, the best blood source for L. ovallesi was chicken and the least satisfactory one was horse. These results contribute to the understanding of the factors that influence the rearing of the sand fly L. ovallesi under laboratory conditions, and of how dietary factors for adult sand flies affect their biological potential and could have important consequences on the transmission of Leishmania.

Key words: Blood, Psychodidae, biology, fertility, Leishmania.

Efecto del tipo de sangre en la supervivencia y fecundidad del flebotomino Lutzomyia

ovallesi Ortiz (Diptera: Psychodidae) vector de Leishmania

Introducción. El potencial reproductivo de los flebotominos depende de varios factores, uno de los cuales es el tipo de hospedador disponible como fuente sanguinea, este es importante en determinar su capacidad de servir como vectores.

Objetivo. Se estudia el efecto de la fuente de alimentación sanguínea sobre varios parámetros biológicos de L. ovallesi en condiciones de laboratorio.

Materiales y métodos. Se utilizaron hembras de dos días de edad de L. ovallesi de colonia, alimentadas artificialmente a repleción usando membrana de pollo, con sangre de siete hospedadores vertebrados, caballo, perro, vaca, gallina, chivo, cochino y humano. Se determinó el tiempo de vida, tiempo de oviposición, tiempo de digestión sanguínea, número de huevos puestos, número de huevos retenidos y número de huevos totales.

Resultados. Los resultados muestran la influencia de la fuente sanguínea sobre diferentes parámetros biológicos de L. ovallesi estudiados. Los resultados demuestran que con la sangre de gallina se obtienen mayor tiempo de oviposición (5,88 días), digestión más rápida (3,34 días), mayor número de huevos retenidos (10,20 huevos por hembra) y mayor fecundidad (30,80 huevos por hembra) en comparación con los otros tipos de sangre. La sangre más satisfactoria fue la de gallina seguida, en orden descendente, por las de chivo, vaca, cochino, humano, perro y caballo.

Conclusión. Los datos muestran que la sangre de gallina es la mejor fuente sanguínea en términos bio-ecológicos para L. ovallesi, y la sangre de caballo la menos adecuada. Los resultados contribuyen al entendimiento de los mecanismos que influyen en las condiciones de cría en el laboratorio del flebotomino L. ovallesi y también de cómo ciertos factores de la dieta en los adultos afectan el potencial biológico y que podrían tener importante consecuencias en la transmisión de Leishmania.

Palabras clave: sangre, Psychodidae, biología, fertilidad, Leishmania.

Sandflies (Diptera: Psychodidae) are hematophagic insects that need bloodmeal to complete their reproductive cycle. Only the females feed on blood which provides proteins indispensable for egg production (1-3). The reproductive potential of sandflies, as other hematophagic insects, depend mainly to find a host that will provide blood capable to mature a significant number of eggs besides a suitable site for laying them (4-7). The feeding habits of the vectors constitute an important aspect of their bionomics, affecting directly the Leishmania transmission (8-10). It also was demonstrated that the rate of blood meal digestion in Phlebotomus langeroni varied according to the source of the vertebrate blood and Leishmania species involved (11).

Chaniotis 1967(12) noticed that Lutzomyia vexator laid more eggs after feeding on lizards than on snakes. Ward 1977 (13) reported that L. flaviscutellata laid more eggs after feeding on rodents than on humans. Ready 1979 (14) observed that for L. longipalpis the number of eggs matured with the blood of seven mammal hosts increased in direct proportion to the weight of blood ingested and its source, some blood seems to be more nutritive than others; similarly, Benito De Martin et al. 1994 (15) and Hanafi et al. 1999 (16) showed for Phlebotomus that fecundity also dependeds on the blood source. Nutritional quality of blood varies between host species and may influence egg productivity, reduce development rates, longevity and fecundity of the insects (17). For understanding the role of blood meal sources on sandfly biology, physiology and Leishmania transmission more field observations and laboratory studies comparing egg productivity of sandflies fed on differents hosts (17-19) are necessary.

L. ovallesi (Ortiz) is one of the main vectors of Leishmania braziliensis in Venezuela (20). It is frequently found in the vicinity of human habitation and it is considered an anthropophilic species (21,22). However, L. ovallesi feeds upon a variety of vertebrate hosts, and could be considered as an opportunistic species (23,24). Thus, the present work studies the effect of blood from different domestic animals on the fecundity of L. ovallesi in laboratory conditions.

Materials and methods

Sandflies

Females of L. ovallesi were obtained from a closed laboratory colony established with specimens collected during 2001 at 1,360 m above sea level in the locality of El Arenal, Ejido, Mérida state, Venezuela. The colony was maintained in the Laboratorio de Parasitología Experimental, at the Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida, Venezuela, with techniques described by Killick-Kendrick et al. in 1977 (25), in an incubator at 25±1°C with a relative humidity of 80±10%.

Blood sources

Blood from healthy animals was collected in tubes containg 0.2 ml of citrate per ml of blood. The blood sources were: horse ( Equus caballus), chicken ( Gallus domesticus), pig ( Sus scrofa domestica), cow ( Bos taurus), goat ( Capra hircus), dog (Canis familiaris) and human ( Homo sapiens sapiens).

Artificial feeding

Two-day-old females were artificially fed to repletion using chicken membrane, with water circulating at a temperature of 39°C. Groups of »100 sand flies were exposed to the feeder over each carton during 4 hours. In each fedeer blood was mixed every 30-45 minutes using a pipette, to prevent cell sedimentation. Blood-fed sandflies were separated, counted and individually placed into glass tubes, mantained in an incubator at 25±1°C with relative humidity of 80±10%, with 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness. As a dietary supplement they were given a 50% fresh sucrose solution, renewed daily.

Fecundity, oviposition time and survival

Daily observations were made to determine the time of blood digestion which was estimated checking each one of the females under the light microscope to determine the presence of blood in the midgut; the oviposition time, which represents the time from blood feeding to egg laying; and survival represents the longevity of the females. After oviposition and death of the females, the eggs were counted, the females removed and dissected in PBS solution using a stereoscopic microscope and the number of retained eggs counted for determination of the fecundity (the number of eggs laid and retained). All results represents the average per female of a minimum of 60 females and a maximum of 139 females.

Statistical analysis

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, with a Tukey test for different N, and finally a principal component analysis, using Minitab Statistical Software (version 10), the statistics program (version 6.0) and SPSS (version 8 in Spanish).

Results

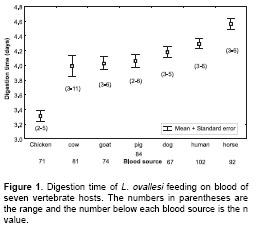

Digestion time. The digestion time by L. ovallesi females fed on the blood of seven vertebrate hosts is presented in figure 1. The digestion time for L. ovallesi in ascending order of duration is as follows: hicken<pig<cow< goat<dog< human<horse (figure 1). Statistical analysis showed that there was only a significant difference between the digestion time for chicken blood and all the others, and between digestion time of horse blood and blood from chicken, pig, cow, and goat (p<0.0005).

Oviposition time.

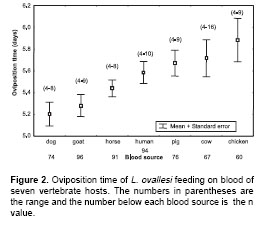

Figure 2 shows the oviposition time by L. ovallesi females fed on the blood of seven vertebrate hosts. The longest oviposition time was obtained with chicken blood and the shortest, with goat and dog blood. In ascending order, the time of oviposition for L. ovallesi with the different sources of blood was as follows: dog<goat<horse<human<pig<cow<chicken. Statistically significant differences (p<0.05) were observed for oviposition time for L. ovallesi fed on chicken, goat, and dog blood.

Number of eggs laid.

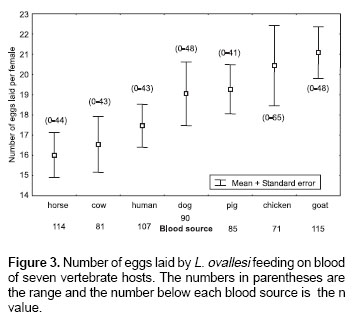

Figure 3 shows the average number of eggs laid by L. ovallesi females fed on the blood of seven vertebrate hosts. The lowest average occurred with horse blood and the highest with goat. The number of eggs laid in decreasing order was as follows: goat>chicken>pig>dog> human>cow>horse. No significant differences were found between the groups.

Number of eggs retained.

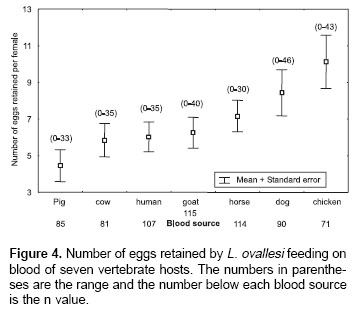

Figure 4 shows the average number of eggs retained by L. ovallesi females fed on blood of the seven vertebrate hosts. The lowest number of eggs retained occurred with pig blood and the highest with chicken. The number of eggs retained in increasing order was as follows: pig<cow<human <goat<horse<dog<chicken. Statistical analysis showed only a significant difference in the average number of eggs retained by L. ovallesi fed on blood of chicken and those fed on pig blood (p<0.01).

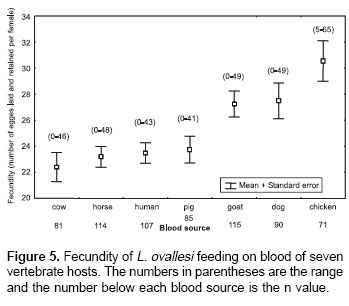

Fecundity.

Figure 5 shows fecundity values (the number of eggs laid and retained) for L. ovallesi females fed on the blood of different vertebrate hosts. The fecundity values in decreasing order were as follows: chicken>dog>goat>pig> human >horse>cow. Statistical analysis shows significant differences in the fecundity of L. ovallesi fed on chicken blood compared with the values obtained from cow, horse, human and pig blood. There were also significant differences between the values obtained from cow and chicken blood, and between dog and goat blood (p<0.05).

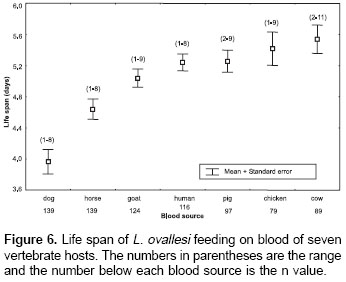

Life span.

The average values for life span of L. ovallesi fed on blood of the seven vertebrate hosts were analyzed (figure 6). The longest life span occurred with cow blood and the lowest, with dog. The average life span of L. ovallesi fed on different types of blood in decreasing order was as follows: cow>chicken>pig>human>goat>horse>dog. Statistical analysis showed that there was a significant difference in the average values obtained from dog blood and the other sources, and between the average values obtained from horse and chicken blood and from cow and dog blood (p<0.05).

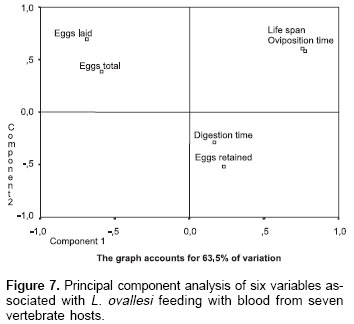

Principal component analysis.

Figure 7 shows the principal component analysis of 6 variables studied in L. ovallesi fed on blood of the seven vertebrate hosts. This analysis was made on the basis of data obtained after the third day of feeding on blood. The figure is made up from two components which account for 63.35% of variation.

Discussion

Fecundity and longevity in sandflies are important factors in determining their capacity to serve as vectors. The results of the present work show that in L. ovallesi, chicken blood is the most quickly digested and gives the longest time of oviposition, the greatest number of eggs retained and the greatest fecundity compared with the other sources of blood studied. These results agree with those of other researchers, who suggest that blood source modifies some biological parameters in sandflies (14-16). Females of L. ovallesi fed on dog blood showed significant differences, with the shortest time of oviposition and the shortest life span. Those fed on cow blood showed significant differences in terms of lower fecundity with those fed on chicken, dog and goat blood. L. ovallesi fed on horse blood showed significant differences between those fed on chicken and cow blood in terms of a shorter life span, between those fed on pig and goat blood in terms of longer digestion time, and with those fed on dog blood in terms of a longer life span.

Ready (14) suggests that these differences in egg production by L. longipalpis fed on hamster and human blood could be due to differences in redcell content and not to L-isoleucine deficiency in human red cells, since adding it did not increase the number of mature eggs. The small specific differences among the seven vertebrate blood sources would explain the results obtained for L. ovallesi. These agree with those of Ready (14), who showed that for L. longipalpis the amount and composition of blood were the principal factors that influenced egg-production in laboratory-bred females. He suggests that physiological factors, such as sugar feeding, size, autogeny and copulation, are less important.

The biological potential of Lutzomyia depends on various factors, one of which is the type of host available as a blood source, where specific differences in blood values are related with the synthesis and rupture of the peritrophic matrix, and the synthesis of digestive enzymes. The enzymatic processes of sandfly guts were shown to function differently, when triggered by different types of meals (8,19,26). The protease levels in the gut of P. langeroni vary in accordance with the blood of the vertebrate host (11). However, the blood meals from different species of vertebrate have no deleterious effect on the development of Leishmania braziliensis or Leishmania amazonensis in the gut of Lutzomyia migonei and parasite development was compatible with digestion, independent of the bloodmeal source (10).

Although, a high number of sandfly species have been successfully colonized during the last decade, the factors limiting their productivity and fecundity in the laboratory are unknown. Also, information on basic aspects of the biology of the sandfly vectors is important to understand the efficiency of transmission of Leishmania and vector competence (27-29). The results of the present work show the influence of blood source on different biological parameters of L. ovallesi, with chicken blood having the most significant effect on several of the parameters studied. However, no single blood source provided optimum results for all the variables studied. On the basis of the principal component analysis, and taking into account ideal or most adequate values for a specific blood source, they would be those that gave, in order of importance: (1) longest life span, (2) shortest oviposition time, (3) shortest digestion time, and (4) greatest number of eggs in total (fecundity). In this analysis, for L. ovallesi fed on seven types of blood, the best in bioecological terms would be chicken, and the least satisfactory, horse; the most satisfactory in descending order being as follows: chicken, goat, cow, pig, human, dog, and horse.

Nutritional quality of blood varies between host species, avian blood should be less nutritious than that of mammals (17). Chicken erythrocytes are nucleate and have a DNA content 31 times higher than the contents found in humans (8,17). They also have a lower hemoglobin content than mammalian red cells and half hematocrit value in comparison to mammals, total plasma protein levels in chickens are considerably lower than in dogs and pigs. In addition, catabolism of nucleic acids from chicken erythrocytes would presumably involve greater bioenergetic cost due to increased production and active transport of uric acid, the end product of nitrogen metabolism (17). In a comparative study of the fecundity and survival rates of P. papatasi fed on blood from eight species of mammals (human, horse, cow, pig, dog, rabbits, guinea-pigs and hamsters) appreciable differences were not detected (30). We found that L. ovallesi can be fed on a variety of source blood, and the chicken blood appears to be more competent. Extrapolating these results, it could be assumed that the effect would be similar in natural conditions, but these aspects need further study to determine the relative importance from chicken and other hosts as bloodmeal sources.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carlos Araque for assistance in the production in laboratory colony, Luis Chávez for his help and cooperation, and to professors Efrain Entralgo, Guillermo Bianchi and Paolo Ramoni for guidance in statistical analyses; to professor Leida Quintero for help in providing blood samples and Irlanda Márquez for proofreading this article.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Financial support

This study was supported by grant of CDCHTULA (Cod: C-1406-06-03-B) and CONICIT (Cod.:S1-2000000818).

Corresponding:

Elsa Nieves, Laboratorio de Parasitologia Experimental (LAPEX), Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias Universidad de Los Andes, La Hechicera, Mérida, Estado Mérida, 5101. Venezuela.

Teléfono: (02 74) 240 1244; fax: (02 74) 240 1286.

nevelsa@ula.ve

References

1. Adler S. Leishmania. Adv Parasitol 1964;2:35-96. [ Links ]

2. Killick-Kendrick R. Biology of Leishmania in phlebotomine sandflies. En: Lumsden WH, Evans DA, editors. Biology of the Kinetoplastida. London: Academic Press; 1979. p.395-460. [ Links ]

3. Young DG, Duncan MA. Guide to the identification and geographic distribution of Lutzomyia sand flies in Mexico, the West Indies, Central and South America (Diptera: Psychodidae). Mem Ann Ent Inst 1994;54:881. [ Links ]

4. Van Handel E. Metabolism nutrients in the adult mosquito. Mosquito News 1984;44:573-9. [ Links ]

5. Briegel H. Fecundity, metabolism, and body size in Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae), vector of malaria. J Med Entomol 1990;27:839-50. [ Links ]

6. Briegel H, Horler E. Multiple blood meal as reproductive strategy in Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol 1993;30:975-85. [ Links ]

7. Kassem HA, Hassan AN. Ovarian development and blood-feeding activity in Phlebotomus bergeroti Parrot (Diptera: Psychodidae) from Egypt. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2003;97:521-6. [ Links ]

8. Schlein Y, Warburg A, Schnur LF, Shlomai J. Vector compatibility of Phlebotomus papatasi dependent on differentially induced digestion. Acta Trop 1983;40:65-70. [ Links ]

9. Volf P, Svobodova M, Dvorakova E. Bloodmeal digestion and Leishmania major infections in Phlebotomus duboscqi: effect of carbohydrates inhibiting midgut lectin activity. Med Vet Entomol 2001;15:281-6. [ Links ]

10. Nieves E, Pimenta PFP. Influence of vertebrate blood meals on the development of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis and Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis in the sand fly Lutzomyia migonei (Diptera: Psychodidae). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2002;67:640-7. [ Links ]

11. Daba S, Mansour NS, Youssef FG, Shanbaky NM, Shehata MG, el Sawaf BM. Vector-host-parasite interelationships in leishmaniasis. III. Impact of blood meal from natural vertebrate host on survival and the development of Leishmania infantum and L. major in Phlebotomus langeroni (Diptera: Psychodidae). J Egypt Soc Parasitol 1997;27:781-94. [ Links ]

12. Chaniotis BN. The biology of California Phlebotomus (Diptera: Psychodidae) under laboratory conditions. J Med Entomol 1967;4:221-33. [ Links ]

13. Ward RD. The colonization of Lutzomyia flaviscutellata (Diptera: Psychodidae), a vector of Leishmania mexicana amazonensis in Brazil. J Med Entomol 1977;14:469-76. [ Links ]

14. Ready PD. Factors affecting egg production of laboratory- bred Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae). J Med Entomol 1979;16:413-23. [ Links ]

15. Benito-De Martín MI, Gracia-Salinas MJ, Molina- Moreno R, Ferrer-Dufol M, Lucientes-Curdi J. Influence of the nature of the ingested blood on the gonotrophic parameters of Phlebotomus perniciosus under laboratory conditions. Parasite 1994;1:409-11. [ Links ]

16. Hanafi HA, Kanour WW Jr, Beavers GM, Tetreault GE. Colonization and bionomics of the sandfly Phlebotomus kazeruni from Sinai, Egypt. Med Vet Entomol 1999;13:295-8. [ Links ]

17. Alexander B, Carvalho RL, McCallum H, Pereira MH. Role of the domestic chicken ( Gallus gallus) in the epidemiology of urban visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8:1480-5. [ Links ]

18. Agrela I, Sánchez E, Gómez B, Feliciangeli MD. Multiple blood meals as a reproductive strategy in Anopheles (Diptera:Culicidae). J Med Entomol 2001; 30:975-85. [ Links ]

19. Hurd H. Manipulation of medically important insect vectors by their parasites. Annu Rev Entomol 2003;48:141-61. [ Links ]

20. Nieves E, Dávila-Vera D, Palacios-Prü E. Daño ultraestructural del intestino medio abdominal de Lutzomyia ovallesi (Ortiz) (Diptera: Psychodidae) ocasionado por Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. Parasitol Latinoam 2004;59:115-22. [ Links ]

21. Feliciangeli MD. La fauna flebotómica (Diptera, Psychodidae) en Venezuela: 1. Taxonomía y distribución geográfica. Bol Dir Malariol San Amb 1988;28:99-113. [ Links ]

22. Feliciangeli MD. Vector of leishmaniases in Venezuela. Parassitologia 1991;33:229-36. [ Links ]

23. Añez N, Cazorla D, Nieves E, Chataing B, Castro M, De Yarbuh AL. Epidemiología de la leishmaniasis tegumentaria en Mérida, Venezuela. I. Diversidad y dispersión de especies flebotominas en tres pisos altitudinales y su posible role en la transmisión de la enfermedad. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1988;83:455-63. [ Links ]

24. Noguera P, Chaves L, Nieves E. Effects of blood ingestion on patterns on the chorion of eggs of Lutzomyia ovallesi (diptera: psychodidae). Parasitol Latinoam 2003;58:49-53. [ Links ]

25. Killick-Kendrick R, Leaney AJ, Ready PD. The establishment, maintenance and productivity of laboratory colony of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae). J Med Entomol 1977;13:429-40. [ Links ]

26. Schlein Y, Jacobson RL. Resistance of Phlebotomus papatasi to infection with Leishmania donovani is modulated by components on the infective bloodmeal. Parasitol 1998;117:467-73. [ Links ]

27. Nieves E. Problemas de colonización de especies flebotominas bajo condiciones de laboratorio, con especial referencia a Lutzomyia youngi, Lutzomyia ovallesi y Lutzomyia migonei (trabajo para ascender de categorí). Mérida, Venezuela: Universidad de los Andes;1995. p.113. [ Links ]

28. Montoya J, Cadena H, Jaramillo C. Rearing and colonization of Lutzomyia evansi (Diptera: Psychodidae), a vector of visceral leishmaniasis in Colombia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1998;93:263-8. [ Links ]

29. Luitgards-Moura JF, Castellon EG, Rosa-Freitas MG. Aspects related to productivity for four generations of a Lutzomyia longipalpis laboratory colony. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2000;95:251-7. [ Links ]

30. Harre JG, Dorsey KM, Armstrong KL, Burge JR, Kinnamon KE. Comparative fecundity and survival rates of Phlebotomus papatasi sandflies membrane fed on blood from eight mammal species. Met Vet Entomol 2001;15:189-96. [ Links ]